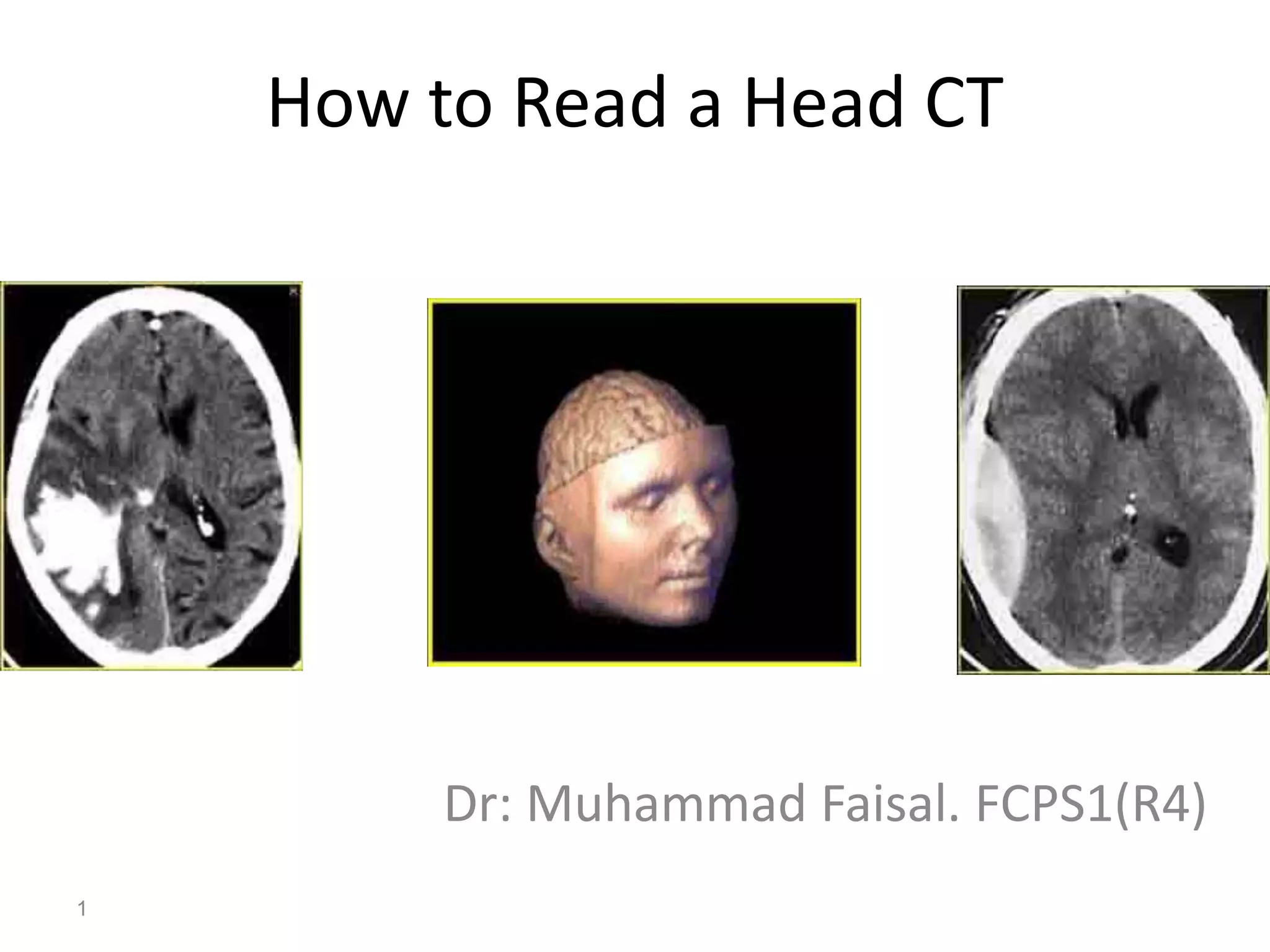

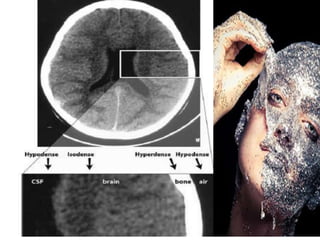

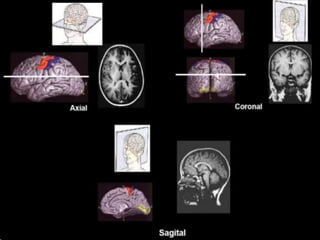

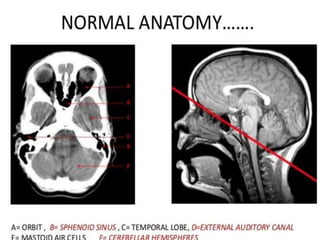

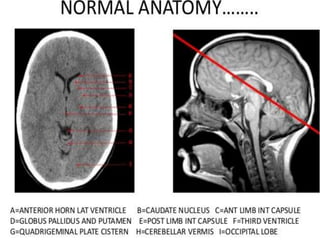

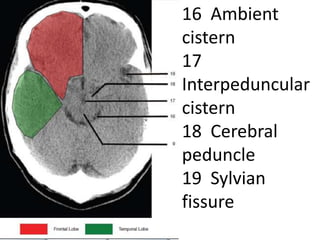

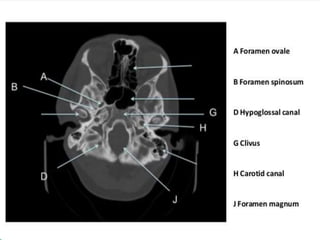

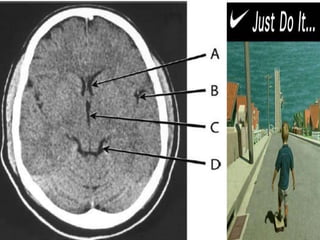

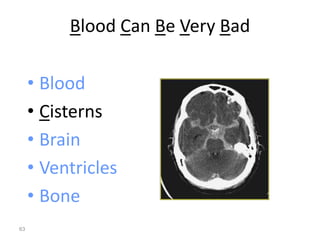

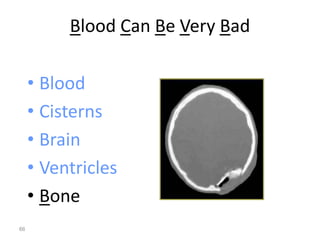

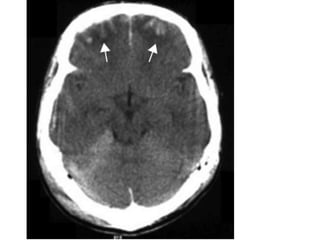

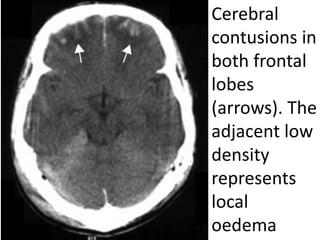

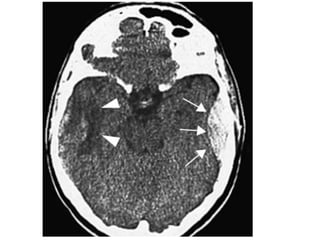

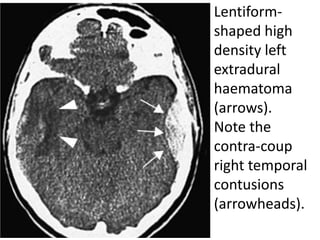

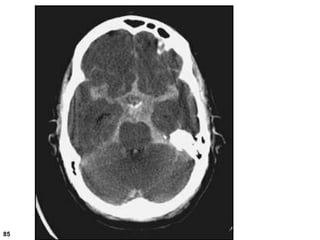

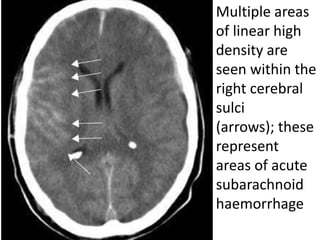

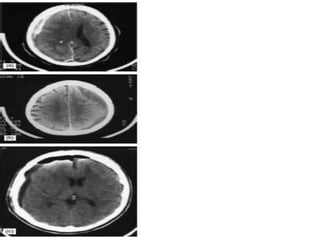

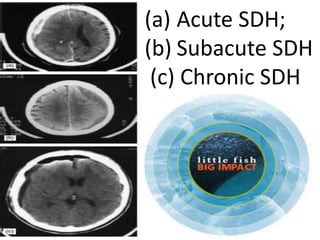

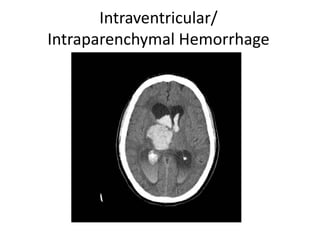

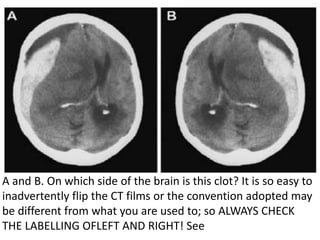

The clot is on the right side of the brain. The labeling at the top of the image indicates "R" for right. It's important to always verify the left/right labeling when interpreting images to avoid potential mistakes from flipped or differently labeled images.