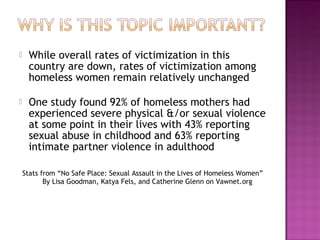

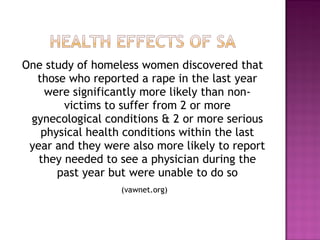

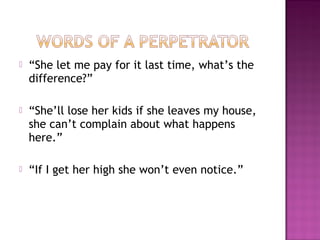

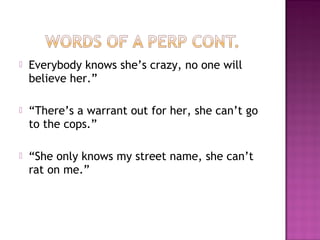

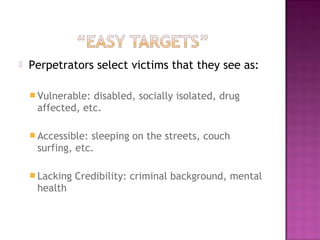

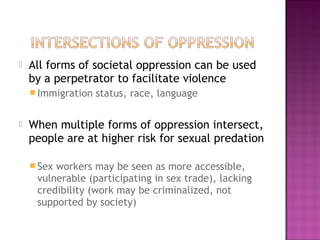

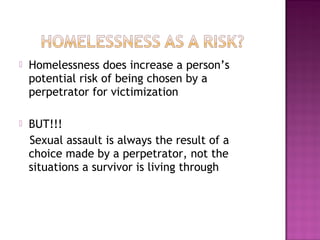

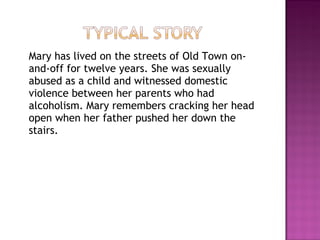

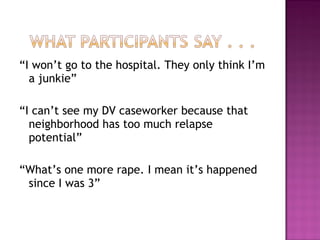

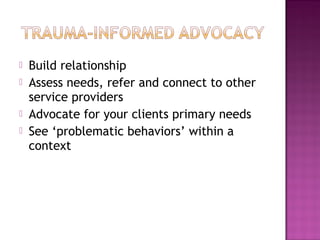

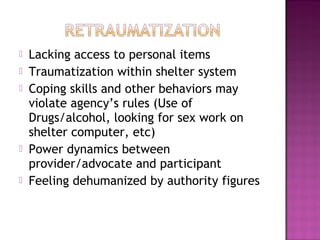

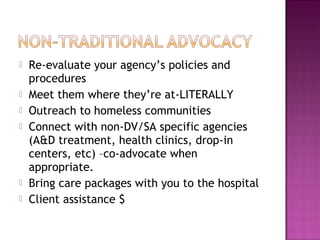

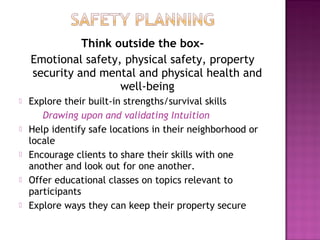

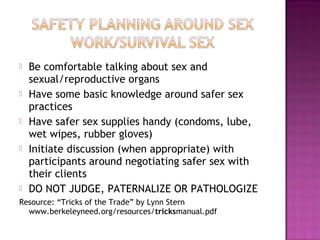

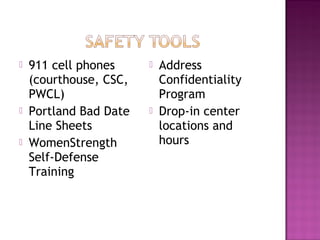

The document discusses the risks faced by homeless survivors of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, and sexual assault, highlighting barriers to accessing services and the effects of trauma. It notes that while overall victimization rates have decreased, homeless women remain highly vulnerable, with many experiencing severe violence and trauma-related health issues. Advocacy strategies are proposed to improve service access and safety planning for these survivors, stressing the importance of recognizing and addressing their unique needs.