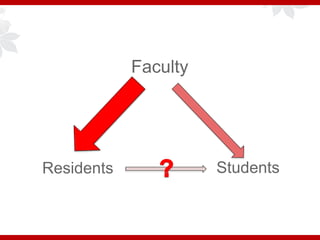

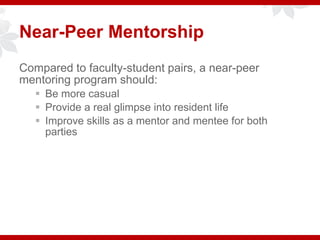

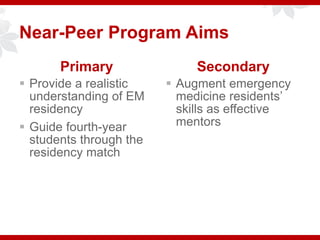

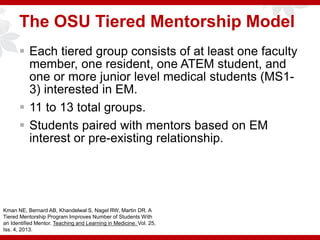

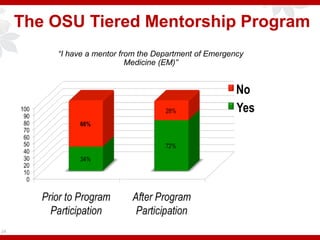

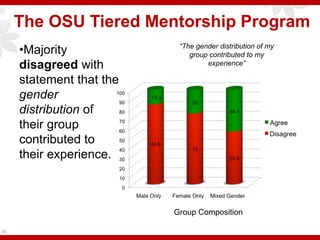

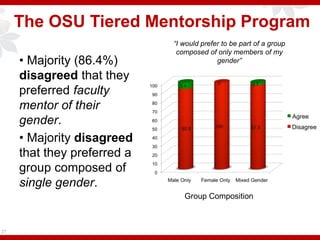

This document describes different approaches to mentorship programs in emergency medicine. It discusses a near-peer mentorship program that pairs fourth-year medical students with emergency medicine residents to provide guidance on residency. It also describes a tiered mentorship model at Ohio State University involving faculty, residents, and students of various levels. This model forms small mixed-gender groups with one faculty mentor and one resident mentor. An evaluation found that students were not influenced by the gender makeup of their group and preferred identifying with faculty mentors regardless of gender. The document introduces challenges with assigning mentors and managing group sizes and dynamics.