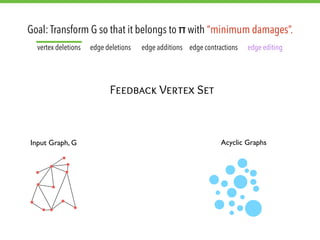

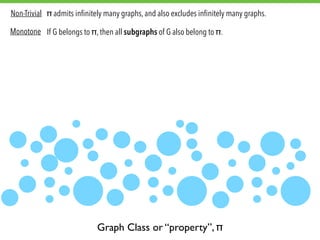

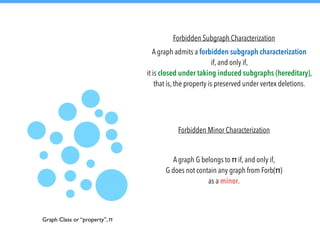

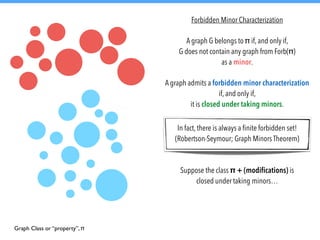

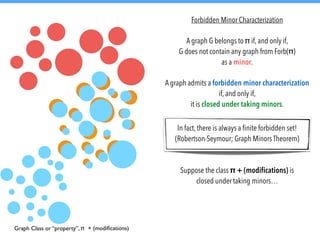

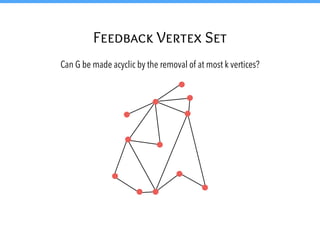

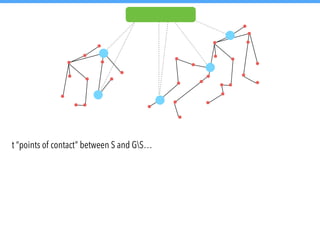

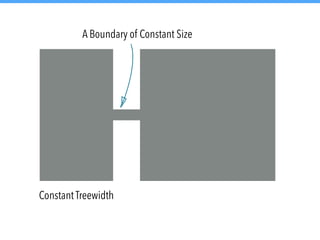

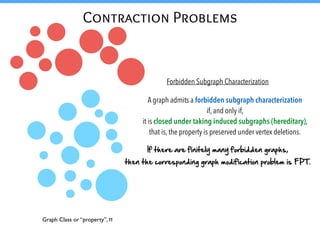

The document explores graph modification problems, focusing on the goal of transforming an input graph to belong to a specified class or property with minimal changes. It discusses various modification operations, such as vertex deletions and edge additions, and their implications on different graph classes and properties. Additionally, the document touches on algorithmic complexity and problem-solving approaches related to graph classification and modification.

![Lewis &

Yannakakis

[1980]

The vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for non-trivial,

hereditary properties.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-42-320.jpg)

![Lewis &

Yannakakis

[1980]

The vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for non-trivial,

hereditary properties.

Yannakakis

[1979]

The connected vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for

non-trivial properties that hold on connected induced

subgraphs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-43-320.jpg)

![Lewis &

Yannakakis

[1980]

The vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for non-trivial,

hereditary properties.

Yannakakis

[1979]

(Edgeless, Acyclic, etc.)

The connected vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for

non-trivial properties that hold on connected induced

subgraphs.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-44-320.jpg)

![Lewis &

Yannakakis

[1980]

The vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for non-trivial,

hereditary properties.

Yannakakis

[1979]

(Edgeless, Acyclic, etc.)

The connected vertex-deletion problem is NP-complete for

non-trivial properties that hold on connected induced

subgraphs.(

Trees, Stars, etc.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-45-320.jpg)

![Edge-Deletion or Completion problems are sometimes easier than their

vertex-deletion counterparts.

Add edges to make the input graph a cluster graph.

Remove edges to make the input graph edgeless.

Remove edges to make the input graph acyclic.

Alon, Shapira

& Sudakov

[2009]

Given a property ᴨ such that ᴨ holds for every

bipartite graph, the Minimum ᴨ-Deletion problem is NP-hard.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-53-320.jpg)

![Edge-Deletion or Completion problems are sometimes easier than their

vertex-deletion counterparts.

Add edges to make the input graph a cluster graph.

Remove edges to make the input graph edgeless.

Remove edges to make the input graph acyclic.

Alon, Shapira

& Sudakov

[2009]

Given a property ᴨ such that ᴨ holds for every

bipartite graph, the Minimum ᴨ-Deletion problem is NP-hard.

(Triangle-free)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-54-320.jpg)

![Edge-Deletion or Completion problems are sometimes easier than their

vertex-deletion counterparts.

Add edges to make the input graph a cluster graph.

Remove edges to make the input graph edgeless.

Remove edges to make the input graph acyclic.

Alon, Shapira

& Sudakov

[2009]

Given a property ᴨ such that ᴨ holds for every

bipartite graph, the Minimum ᴨ-Deletion problem is NP-hard.

Colbourn &

El-Mallah

[1988]

(Triangle-free)

Making a graph Pk-free by deleting the minimum number of

edges is NP-hard for every k > 2.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-55-320.jpg)

![Consider the property ᴨ of being wheel-free, that is,

not having any wheel as an induced subgraph.

Wheel-Free Deletion and Wheel-Free Vertex Deletion

are W[2]-hard.

Lokshtanov

(2008)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-83-320.jpg)

![Finding large induced subgraphs with property ᴨ.

Khot and Raman, (2002)

If ᴨ is a hereditary property that contains all independent sets and all cliques,

or if ᴨ excludes some independent sets and some cliques,

then the problem of finding an induced subgraph of size at least k, satisfying ᴨ,

is FPT.

If ᴨ is a hereditary property contains all independent sets but not all cliques

(or vice versa),

then the problem of finding an induced subgraph of size at least k, satisfying ᴨ,

is W[1]-hard.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-86-320.jpg)

![Finding large induced subgraphs with property ᴨ.

Khot and Raman, (2002)

If ᴨ is a hereditary property that contains all independent sets and all cliques,

or if ᴨ excludes some independent sets and some cliques,

then the problem of finding an induced subgraph of size at least k, satisfying ᴨ,

is FPT.

If ᴨ is a hereditary property contains all independent sets but not all cliques

(or vice versa),

then the problem of finding an induced subgraph of size at least k, satisfying ᴨ,

is W[1]-hard.

Ramsey Numbers!

Reduction from Independent Set](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-87-320.jpg)

![Thanks to Graph Minors, we have a f(k)n2 algorithm for the 퓕-Deletion problem.

For Planar 퓕-Deletion, the starting point was a double-exponential algorithm.

[Bodlaender, 1997]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-143-320.jpg)

![Thanks to Graph Minors, we have a f(k)n2 algorithm for the 퓕-Deletion problem.

For Planar 퓕-Deletion, the starting point was a double-exponential algorithm.

[Bodlaender, 1997]

Many single-exponential algorithms are known for special cases of 퓕.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-144-320.jpg)

![Thanks to Graph Minors, we have a f(k)n2 algorithm for the 퓕-Deletion problem.

For Planar 퓕-Deletion, the starting point was a double-exponential algorithm.

[Bodlaender, 1997]

Many single-exponential algorithms are known for special cases of 퓕.

Feedback Vertex Set has Cao, Chen & Liu a O*(3.83k) algorithm.

[2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-145-320.jpg)

![Thanks to Graph Minors, we have a f(k)n2 algorithm for the 퓕-Deletion problem.

For Planar 퓕-Deletion, the starting point was a double-exponential algorithm.

[Bodlaender, 1997]

Many single-exponential algorithms are known for special cases of 퓕.

Cao, Chen & Liu Feedback Vertex Set has a O*(3.83k) algorithm.

[2010]

{K4}-Deletion has Kim, Paul & Philip a O*(2O(k)) algorithm.

[2012]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-146-320.jpg)

![Thanks to Graph Minors, we have a f(k)n2 algorithm for the 퓕-Deletion problem.

For Planar 퓕-Deletion, the starting point was a double-exponential algorithm.

[Bodlaender, 1997]

Many single-exponential algorithms are known for special cases of 퓕.

Cao, Chen & Liu Feedback Vertex Set has a O*(3.83k) algorithm.

[2010]

{K4}-Deletion has Kim, Paul & Philip a O*(2O(k)) algorithm.

Pathwidth-1-Deletion has a O*(4.65k) algorithm.

[2012]

Cygan, Pilipczuk,

Pilipczuk & Wojtaszczyk

[2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-147-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-149-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-150-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n log2n) algorithm

when every graph in 퓕 is connected.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-151-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n log2n) algorithm

when every graph in 퓕 is connected.

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an O(nm) randomized algorithm

that leads us to a constant-factor approximation.

Can we get a deterministic

constant-factor approximation algorithm?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-152-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n log2n) algorithm

when every graph in 퓕 is connected.

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an O(nm) randomized algorithm

that leads us to a constant-factor approximation.

Can we get a deterministic

constant-factor approximation algorithm?

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an deterministic algorithm

that leads us to a O(log3/2(OPT)) approximation.

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M., Philip & Saurabh

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-153-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n log2n) algorithm

when every graph in 퓕 is connected.

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an O(nm) randomized algorithm

that leads us to a constant-factor approximation.

Can we get a deterministic

constant-factor approximation algorithm?

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an deterministic algorithm

that leads us to a O(log3/2(OPT)) approximation.

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M., Philip & Saurabh

[2013]

Kim, Langer, Paul, Reidl,

Rossmanith, Sau, & Sikdar

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n2) algorithm.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-154-320.jpg)

![Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a randomized (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in퓕is connected.

Best possible under ETH.

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n) algorithm

when every graph in 퓕 is connected.

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an O(nm) randomized algorithm

that leads us to a constant-factor approximation.

Can we get a deterministic

constant-factor approximation algorithm?

Planar퓕-Deletion admits an deterministic algorithm

that leads us to a O(log3/2(OPT)) approximation.

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M., Philip & Saurabh

[2013]

Kim, Langer, Paul, Reidl,

Rossmanith, Sau, & Sikdar

[2013]

Planar퓕-Deletion admits a deterministic (2O(k)n2) algorithm.

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M., Ramanujan& Saurabh

[2015]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-155-320.jpg)

![Many polynomial kernels are also known for special cases of 퓕.

Feedback Vertex Set has a Thomasse O(k2) instance kernel.

[2009]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-158-320.jpg)

![Many polynomial kernels are also known for special cases of 퓕.

Thomasse Feedback Vertex Set has a O(k2) instance kernel.

[2009]

Vertex Cover has (Various) a O(k) vertex kernel.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-159-320.jpg)

![Many polynomial kernels are also known for special cases of 퓕.

Thomasse Feedback Vertex Set has a O(k2) instance kernel.

[2009]

Vertex Cover has (Various) a O(k) vertex kernel.

Pathwidth-1-Deletion has a polynomial kernel

Cygan, Pilipczuk,

Pilipczuk & Wojtaszczyk

[2010]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-160-320.jpg)

![Many polynomial kernels are also known for special cases of 퓕.

Thomasse Feedback Vertex Set has a O(k2) instance kernel.

[2009]

Vertex Cover has (Various) a O(k) vertex kernel.

Pathwidth-1-Deletion has a polynomial kernel

Cygan, Pilipczuk,

Pilipczuk & Wojtaszczyk

[2010]

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a polynomial kernel.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-161-320.jpg)

![Many polynomial kernels are also known for special cases of 퓕.

Thomasse Feedback Vertex Set has a O(k2) instance kernel.

[2009]

Vertex Cover has (Various) a O(k) vertex kernel.

Pathwidth-1-Deletion has a polynomial kernel

Cygan, Pilipczuk,

Pilipczuk & Wojtaszczyk

[2010]

Fomin, Lokshtanov,

M. & Saurabh

[2013]

Planar 퓕-Deletion admits a polynomial kernel.

Best possible under standard assumptions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-162-320.jpg)

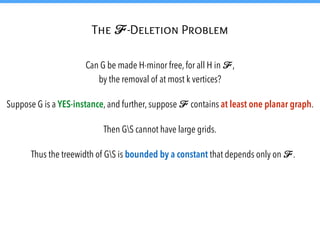

![The 퓕-Deletion Problem

Very little is known beyond the graph minors result.

The most fundamental 퓕-deletion problem that is not accounted for by

Planar 퓕-Deletion is Planarization.

Marx and Schlotter

[2012]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(2g(k)n2) where g(k) = kO(k3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-166-320.jpg)

![The 퓕-Deletion Problem

Very little is known beyond the graph minors result.

The most fundamental 퓕-deletion problem that is not accounted for by

Planar 퓕-Deletion is Planarization.

Marx and Schlotter

[2012]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(2g(k)n2) where g(k) = kO(k3)

Kawarabayashi

[2009]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(f(k)n) where f(k) is not explicitly specified.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-167-320.jpg)

![The 퓕-Deletion Problem

Very little is known beyond the graph minors result.

The most fundamental 퓕-deletion problem that is not accounted for by

Planar 퓕-Deletion is Planarization.

Marx and Schlotter

[2012]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(2g(k)n2) where g(k) = kO(k3)

Kawarabayashi

[2009]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(f(k)n) where f(k) is not explicitly specified.

Jansen, Lokshtanov &

Saurabh

[2014]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

2O(k log k)n, achieving the best combined dependence on k and n.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-168-320.jpg)

![The 퓕-Deletion Problem

Very little is known beyond the graph minors result.

The most fundamental 퓕-deletion problem that is not accounted for by

Planar 퓕-Deletion is Planarization.

The question of kernels is completely open.

Marx and Schlotter

[2012]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(2g(k)n2) where g(k) = kO(k3)

Kawarabayashi

[2009]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

O(f(k)n) where f(k) is not explicitly specified.

Jansen, Lokshtanov &

Saurabh

[2014]

Planarization admits an algorithm with running time

2O(k log k)n, achieving the best combined dependence on k and n.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-169-320.jpg)

![Contraction To C4-free graphs

Can G be made C4-free by the contraction of at most k edges?

W[2]-hard by a simple reduction from Hitting Set.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-174-320.jpg)

![Contraction To C4-free graphs

Can G be made C4-free by the contraction of at most k edges?

W[2]-hard by a simple reduction from Hitting Set.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-175-320.jpg)

![Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-177-320.jpg)

![Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]

Chordal Contraction isW[2]-hard while Clique contraction is FPT

but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Cai and Guo

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-178-320.jpg)

![Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]

Chordal Contraction isW[2]-hard while Clique contraction is FPT

but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Characeterizations are open.

Cai and Guo

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-179-320.jpg)

![Heggernes, van’t Hof,

Lokshtanov & Paul

[2011]

Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Chordal Contraction isW[2]-hard while Clique contraction is FPT

but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Contracting to Bipartite graphs is fixed-parameter tractable with

a double-exponential running time.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]

Characeterizations are open.

Cai and Guo

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-180-320.jpg)

![Heggernes, van’t Hof,

Lokshtanov & Paul

[2011]

Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Chordal Contraction isW[2]-hard while Clique contraction is FPT

but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Characeterizations are open.

Contracting to Bipartite graphs is fixed-parameter tractable with

a double-exponential running time.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]

Polynomial kernels are open.

Cai and Guo

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-181-320.jpg)

![Heggernes, van’t Hof,

Lokshtanov & Paul

[2011]

Ct-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 4 and FPT if t⩽ 3.

Pt-free Contraction isW[2]-hard if t ⩾ 5 and FPT if t ⩽ 4.

Chordal Contraction isW[2]-hard while Clique contraction is FPT

but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Characeterizations are open.

Contracting to Bipartite graphs is fixed-parameter tractable with

a double-exponential running time.

Lokshtanov, M. &

Saurabh

[2013]

Polynomial kernels are open.

Heggernes, van’t Hof,

Lévêque, Lokshtanov

& Paul

[2011]

Contracting to paths is FPT and has a linear-vertex kernel; while

contracting to trees is FPT but is unlikely to admit a polynomial kernel.

Cai and Guo

[2013]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-182-320.jpg)

![Yannakakis

[1981]

Chordal Completion

The minimum fill-in problem is NP-complete

(was left open in the first edition of Garey and Johnson).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-185-320.jpg)

![Yannakakis

[1981]

Chordal Completion

The minimum fill-in problem is NP-complete

(was left open in the first edition of Garey and Johnson).

Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Chordal Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) with

a running time of O(k616k + k2mn).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-186-320.jpg)

![Yannakakis

[1981]

Chordal Completion

The minimum fill-in problem is NP-complete

(was left open in the first edition of Garey and Johnson).

Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Chordal Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) with

a running time of O(k616k + k2mn).

Bodlaender,

Heggernes, & Villanger

[2011]

Chordal Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) with

a running time of O(2.36k + k2mn).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-187-320.jpg)

![Yannakakis

[1981]

Chordal Completion

The minimum fill-in problem is NP-complete

(was left open in the first edition of Garey and Johnson).

Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Chordal Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) with

a running time of O(k616k + k2mn).

Bodlaender,

Heggernes, & Villanger

[2011]

Chordal Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT) with

a running time of O(2.36k + k2mn).

Fomin & Villanger

[2013]

Chordal Completion admits a sub exponential

parameterized algorithm with a running time of O(2√k log k + k2mn).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-188-320.jpg)

![Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Interval Completion

Chordal Completion, Strongly Chordal Completion, and

Proper Interval Completion are fixed-parameter tractable (FPT).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-190-320.jpg)

![Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Interval Completion

Chordal Completion, Strongly Chordal Completion, and

Proper Interval Completion are fixed-parameter tractable (FPT).

Heggernes, Paul,

Telle & Villanger

[2007]

Interval Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT),

with a running time of O(k2kn3m).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-191-320.jpg)

![Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Interval Completion

Chordal Completion, Strongly Chordal Completion, and

Proper Interval Completion are fixed-parameter tractable (FPT).

Heggernes, Paul,

Telle & Villanger

[2007]

Interval Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT),

with a running time of O(k2kn3m).

Cao

[2007]

Interval Completion has a single-exponential parameterized algorithm,

with a running time of O(6k(n+m)).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-192-320.jpg)

![Kaplan, Shamir &

Tarjan

[1999]

Interval Completion

Chordal Completion, Strongly Chordal Completion, and

Proper Interval Completion are fixed-parameter tractable (FPT).

Heggernes, Paul,

Telle & Villanger

[2007]

Interval Completion is fixed-parameter tractable (FPT),

with a running time of O(k2kn3m).

Cao

[2007]

Interval Completion has a single-exponential parameterized algorithm,

with a running time of O(6k(n+m)).

Bliznets, Fomin,

Pilipczuk & Pilipczuk

[2014]

Interval Completion admits a subexponential parameterized algorithm

with a running time of kO(√k)nO(1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/g5csnepyspc0ltr6s0dn-signature-589a2e0a828d35c778544bfcd9130f953b90843638b793665c1663a7419e6a74-poli-141214233504-conversion-gate02/85/Graph-Modification-Algorithms-193-320.jpg)