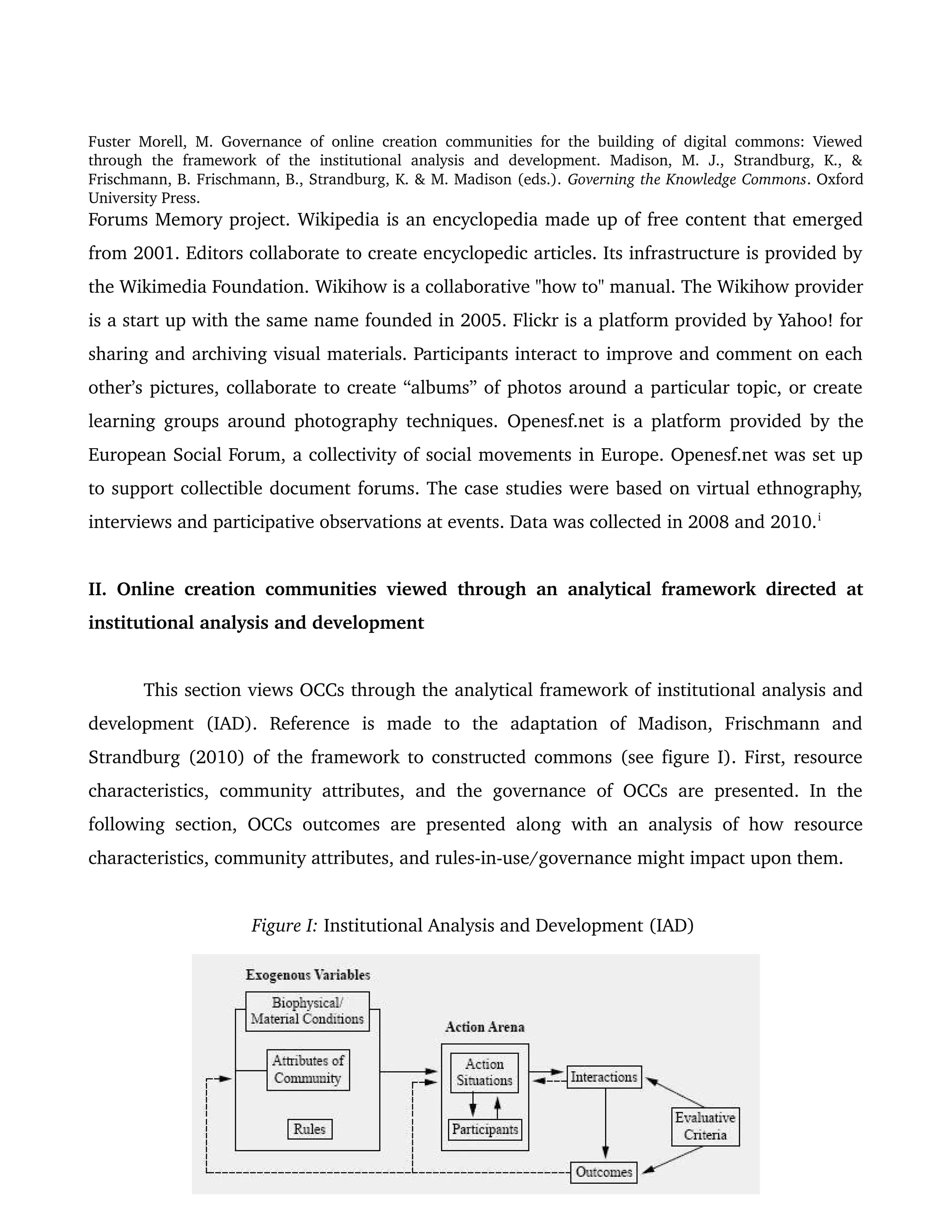

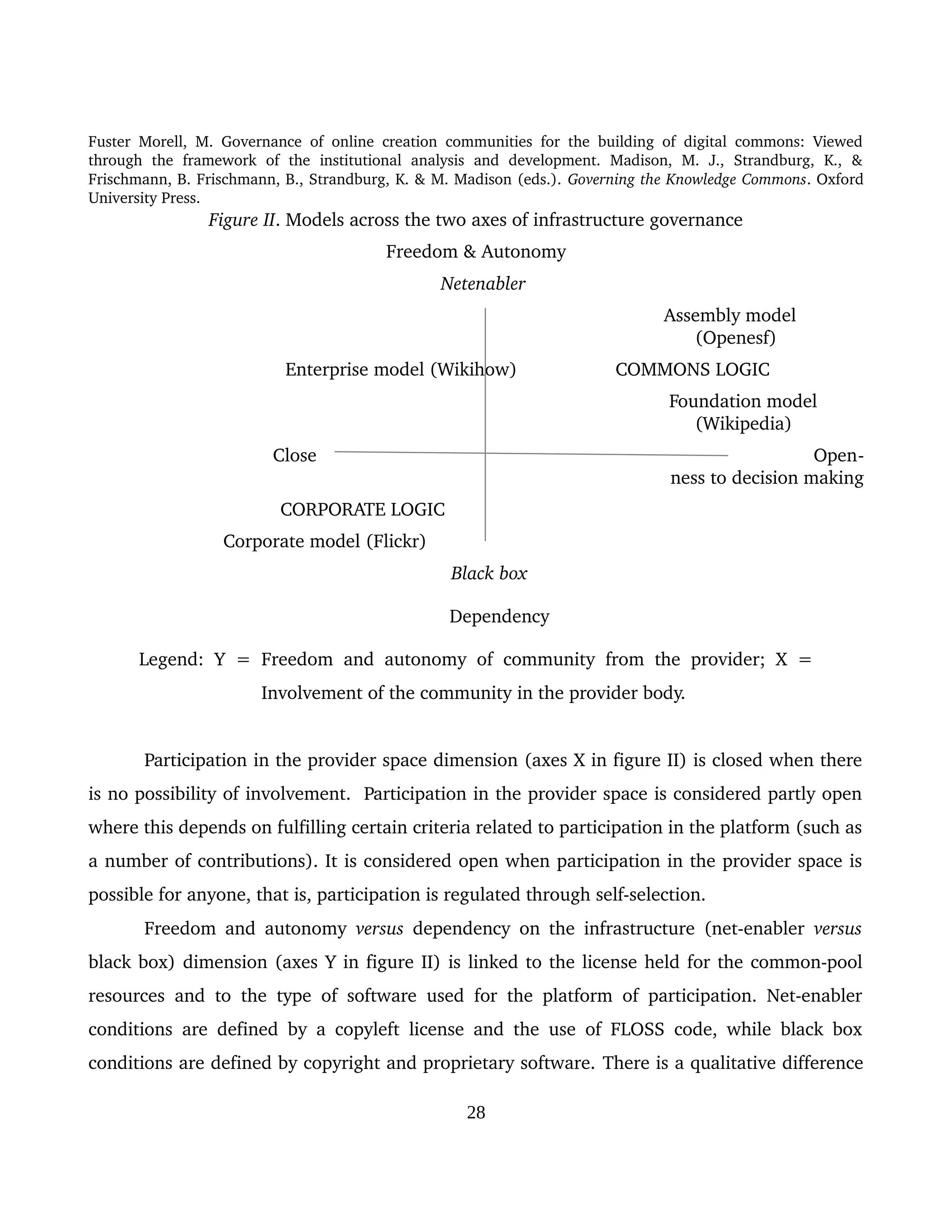

This document analyzes the governance of online creation communities (OCCs) through the institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework. It examines 50 OCC cases and conducts in-depth analyses of 4 cases (Wikipedia, Wikihow, Flickr, OpenESF). The analysis identifies 4 models of OCC governance and assesses the utility of the IAD framework for understanding OCC governance. Additionally, it challenges previous literature for not considering infrastructure provision and questions the neutrality of infrastructure in collective action.