Give Us Work Not Dole: an oral history of the Meccano sit-in

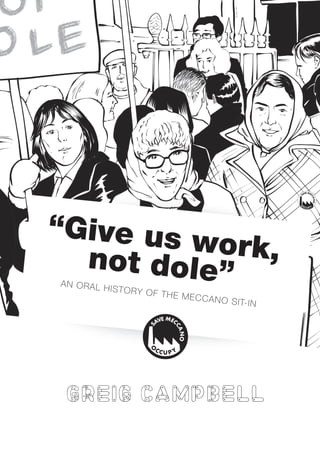

- 1. “Give us work, not dole” AN ORAL HISTORY OF THE MECCANO SIT-IN Greig Campbell

- 2. I2 All rights reserved. This booklet or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the author. Copyright © 2021 by Greig Campbell Printed in Liverpool, UK The author would like to thank the following individuals or organisations: The Barry Amiel & Norman Melburn Trust | David Alton | Frank Bloor | Rosemary Critchley | Anne Culligan | Terry Culligan | Pauline Gerdes | Les Hanrahan | Derek Hatton | Les Jardine | Denise Jones | Richard Knights | Liverpool Central Library & Record Office | John Lynch | John McCaffrey | The Scottie Press | Graham Shepherd | Ian Wilson

- 3. Z 3 This pamphlet is dedicated to the men and women of toytown and all those who supported their struggle

- 4. I4 I4 "These people were my colleagues. Many of them had worked all their lives in Meccano and had been joined by their own children as they grew up. There was one grandad, mum and son who all earned their living together. No this was simply not acceptable!" ROSEMARY CRITCHLEY "Once you’re outside the factory gates, you have no control at all. There was a realisation that it was far better to remain inside, secure the building and use it as a bargaining tool … We escorted management off the premises. They honestly thought that we’d roll over and die. They were in for a shock … I rang my wife and told her, "I’ll be home late tonight. They’ve just shut the factory. I don’t have a job." We were going to have a sit in." JOHN LYNCH

- 5. Z 5 Z 5 THE OCCUPATION IN CONTEXT T hroughout the 1970s and 1980s, Britain experienced several economic crises that resulted in the deindus- trialisation of traditional working-class communities. In some instances, rank-and-file workers responded to the threat of mass redundancies by seizing control of plant and equipment. The fight back began on Merseyside when, in August 1969, employees at General Electric Construction voted to sit-in against a round of compulsory lay-offs.1 As a unique experiment in workplace protest, it inspired a bur- geoning national occupation movement. Three years later, Fisher-Bendix employees in nearby Kirkby coordinated a work-in that resulted in a workers’ cooperative.2 Although in- stances of shop-floor anti-closure struggles declined under Thatcher, Liverpool remained a stronghold for the right to work movement. Campaigns at the likes of Cammell Laird and Mersey Docks prompted historian Brian Marren to re- mark that the city became a “nucleus of resistance against the encroaching tide of monetarism and sweeping deindus- trialisation”.3 Notwithstanding nascent academic interest in collective re- sponses to the decline of Merseyside’s traditional male dominated industries, very little has been written about the experiences of the region’s female workers.4 By reconstruct- ing the events surrounding a November 1979 takeover of Meccano’s Binns Road factory, ‘Give us work not dole’ seeks to remedy this. An unapologetically hagiographic piece, it utilises oral testimonies collected from the predom- inantly female workforce to produce an intimate account of the 102-day occupation. Whilst condemning the actions of malevolent company officials, the booklet celebrates the fortitude of ordinary rank-and-file workers and the people of Liverpool.

- 6. I6 A GIANT WITH FEET OF CLAY T he occupation began on 30 November 1979, as an immediate response to the news that parent company Airfix had ordered the closure of their famous Binns Road Meccano factory after seven decades of continuous production. Speaking to The Socialist Challenge, one local shop-steward relayed how management dropped the bombshell to the approximately 950-strong workforce: “It was 3.45pm last Friday that the managing director of Airfix, the owning company, called in all the senior stewards here to tell us that in three-quarters of an hour the firm would cease to function. When we raised the question of 90- days’ notice, the managing director said, “you’ll have to take us to court”, and while we were sit- ting in the meeting management was issuing everyone on the shop-floor with their redund- ancy notices. That was it.”5 In a duplicitous act of self-preservation, executives portrayed the image of a commercially viable company undermined by indolent employees. Yet this demonstrably false narrative was constructed to divert attention away from their own fail- ings. Under Airfix, Meccano had experienced gross misman- agement, prompting one business historian to contend: Meccano’s problems lay not so much in the envir- onment as in the firm itself. New strategies, more appropriate to the increasingly competitive situ- ation, were slow to emerge. When they did, man- agement lacked both the ability and knowledge to implement them effectively.6

- 7. Z 7 Incompetence at boardroom level manifested itself in a multi- tude of failings. On the commercial front, industry experts be- moaned company’s failure to respond to new market trends: The weakness of Meccano is that it is essentially an Edwardian toy. It was designed for the sons of men sent out to the colonies to build bridges, and it hasn’t changed much since then.7 Likewise, the archaic nature of product development often left workers bemused: “I lay the blame for the disastrous collapse of Meccano on the old-fashioned small-minded management. They held the rights to make Star Trek products from 1969 but chose not to make ‘space stuff’ until about 1976. They threw money into making a ‘Cinderella’ coach but didn’t have the naming rights. It was based on a Hollywood movie of that time, ‘The Slipper and the Rose’. They chose to make the coach out of die-cast metal, a very hard and sharp material. Great for Dinky cars but for a toy aimed at young girls? Totally unsuitable. The women on the assembly line laughed at the product and knew it would not sell. I remember them running out of storage space to put the many box loads of the coaches that were returned from all over Europe.”8 Marketing was similarly anachronistic. The company com- pletely snubbed digital media, instead relying on the out- dated Meccano Magazine, costly international toy fairs and ostentatious shop window displays installed in upmarket de- partment stores: “You’d never see any advertising. I think they missed some opportunities. A lot of the television stuff, Corgi got in first with the likes of the ‘green hornet’.”9

- 8. I8 Meanwhile, a refusal to invest in plant and machinery had left the Binns Road plant in a state of total disrepair, prompting The Times to liken it to “a museum of industrial archaeology”.10 One ex-worker reflects on the obsolescence of the press shop: “They were still using machines from 1910. They had presses there that were belt driven. They were 30 or 40 years old. In my recollection I can’t re- member the press shop ever getting a new ma- chine … It was the same old machines from when Hornby had it.”11 Experienced engineers were forced to adopt a patch and mend policy in a futile attempt to fulfil vital orders: “Machines would leak oil, because the seals were so badly worn, you were plugging them all the time to make them work. You were using your engineer- ing skills to keep them going … At the same time, you’re being criticised for not meeting your pro- duction targets.”12 It was therefore operational mismanagement, rather than the workforce itself, that contributed to chronically low pro- ductivity. Pauline Gerdes recalls how assembly lines would repeatedly grind to a halt: “People had to get shifted from the jobs they were on. Say, on the feeding line, we were doing train sets. You’d be waiting, because you couldn’t com- plete the boxes without this particular part … Once something broke down, you’d be just count- ing nuts and bolts, putting them in a plastic bag. Sometimes it would take a couple of weeks.”13 Airfix, meanwhile, oversaw an incredibly chaotic personnel policy. A managerial merry-go-round witnessed the hiring and firing of eight managing directors in as many years. The final custodian was Ray McNeice, a hatchet man who over- saw the systematic withdrawal of Meccano from Liverpool:

- 9. Z 9

- 10. I10 “He came in with one sole aim: that was to close Meccano down … to try and close it down within a time frame. From the time he came, he kept say- ing that the factory wasn’t running right, and this and that was going wrong.14 He was cute … He got all the shop-stewards to- gether and said, “This is what I’m going to do. I’m going to improve the canteen, the toilet facilities. I’m going to put water fonts around the factory.” … but at the same time he had another plan: he was going to close us down.”15 As a faceless and absent multinational corporation, Airfix en- gendered an industrial relations culture that contrasted greatly to previous owner Frank Hornby’s renowned paternalism: “Management were always trying to do things to wind us up. I remember being taken to one side by one of the senior blokes in there who said, “Watch that fella going around. They pay him an extra so much an hour to feed back to them.” … They were always doing mad little things to upset you. For example, they’d give one department free overalls – you’d take them home and wash them your- self … Then they’d wash [another department’s] overalls for them. They were always doing little things to divide you. All along the way, they were doing little things to wind you up, you know.”16 Company officials would subsequently blame firm’s downfall on poor industrial relations – depicting workers as industrial ogres. In truth, the women of Meccano were incredibly con- scientious, motivated in part by a remuneration package that relied heavily on hitting production targets: “There were no slackers, because the women super- visors wouldn’t let it slack. Winnie Bleasdale, she was one of the main women and she wouldn’t let you do anything out of order. I’m telling you, she was good …

- 11. Z 11 If you didn’t make cars, you didn’t make money. Simple as that. So, they didn’t slack in any way, shape or form. All the women were on bonuses … You had to work hard to earn your wages. You got a flat basic rate, and that was rubbish. You made it up with your bonus.”17 Despite management claims, some of the most loyal em- ployees were trade unionists. Electrical Trades Union (ETU) representative Terry Culligan would regularly work ‘off the clock’ to ensure the line was running smoothly for female co- workers. When faced with a major cashflow crisis in the mid- 1970s, a team of shop-stewards co-authored a survival plan that voluntarily sacrificed hundreds of jobs: “We’d already gone through redundancies. I had to go to my dad and tell him, “Sorry dad, you’re getting made redundant.” You see we had to make a choice … We started off with everyone over 65. My dad was over 65, so I had to go and tell him. It was soul destroying for me … He was a workhorse my dad. His work ethic was fantastic … He loved it. He said to me, “This is the best job I’ve ever had in my life! Why didn’t you get me this job years ago?” He did, honestly. He absolutely loved it … I had to go over to him and say, “Look dad, I’m sorry, but the first ones that have to go are the ones over 65.” He just said, “Alright lad, I understand, don’t worry.””18 Three years later, the same General and Municipal Workers’ Union (GMWU) official told The Socialist Challenge: “They’ve put out in the media that we have been dis- ruptive and have had disputes. It’s not true. We’ve cooperated with management all along the line. This is a stab in the back … They’ve definitely hood- winked us. We’ve had redundancies before, in 1976- 77 for example. We thought at that time that it was the best thing to do because it was saving the ma- jority of people’s jobs. We’ve realised that’s not the right way. You get stabbed. You get killed.”19

- 12. I12

- 13. Z 13 PLANT TAKEOVER In the immediate wake of the announcement, a wave of despair descended over the women: “People started crying. … Even the fellas were cry- ing … “Oh my god, what am I going to do? It’s nearly Christmas. This isn’t fair. This isn’t right! This is why we’ve been working so hard for the last 12-months. They’re moving! They’re going some- where else.””20 Anguish was soon replaced by a sense of outrage that sowed the seeds of mass resistance: “We were all gobsmacked, we never even thought about it [the occupation] at first. But after, say 15- minutes, we were getting our heads around it. “Right, that’s it, we need to do something about this. They’re not getting away with this. They can’t do this. We’re going to sit-in.””21 The first stage of what was an entirely spontaneous plant takeover witnessed shop-stewards escort indignant man- agers off the premises: “Management? … They weren’t happy, let’s put it that way. Other than that, there wasn’t a lot they could do, with a load of hairy young Liverpudlians, telling them to get out. There were a few expletives … They were told in no uncertain terms, if they didn’t go out, they’d get buried. And that’s basically what happened. They were told to get out of the factory.”22 The factory was now under workers’ control. That weekend, a small group maintained a nervous vigil, safeguarding the site and its contents from potential intruders. Then, after

- 14. I14 I14 clocking-in as usual on Monday morning, a mass meeting voted to transform the takeover into a permanent occupa- tion. Shop-stewards promptly welded shut the factory gates, locking inside millions of pounds worth of stock and ma- chinery. On the ground, the protest was coordinated by the likes of Rosa Owens, an Italian-born GMWU stalwart and plant matriarch. Under her supervision, strict rules and a flexible five-shift rota were established. Over the ensuing 99 days, the women of Meccano became poster girls for main- stream press, with The Times christening them the ‘tiny ladies of toytown’.23 A wider, extra-workplace anti-closure campaign was organ- ised by a Joint Shop Stewards Committee headed by the likes of Frank Bloor, John Lynch, Dick Fitzpatrick, Rose Han- ley and Anne Noon. As longstanding shop stewards, this small vanguard possessed a clear and legitimate mandate: “Dick was my shop-steward. Great fella. I abso- lutely loved working with him … he was a wonder- ful character, as hard as nails … You could always go and chat with him, and he’d always lend you an ear … He was a good man, a really good man.”24 Aware of the need to maintain morale, the Committee adop- ted an outwardly optimistic tone throughout the struggle: “We are hopeful. I honestly think it will re-open. I don’t think it is lost. Everyone at the factory seems to have more heart for doing the jobs of sitting-in. We have all got over the hump of Christmas. Spir- its are tremendous now.”25 At this juncture, there was considerable appetite for the sit- in, with one-third of workers actively participating. A discern- ible camaraderie, initially prompted by a collective occupa- tional culture forged by assembly line work, was augmented by the increasingly nefarious behaviour of management: “I think they were extremely underhanded. If you can call them management. I certainly wouldn’t. We

- 15. Z 15 Z 15 were used. Disrespected … Everybody worked hard. Every young girl and young lad. It was mis- managed. They didn’t respect who we were. They didn’t give a damn … We talked about how angry we were. How upset we were. We’d got to stick to- gether … We felt that we could make a point. A point to them, to say, “We’re not the scum of the earth. How dare you treat us like that. We’re human be- ings, and we’ve worked hard.” They had no right.”26 "It was traumatic at the time. We had three kids. I couldn’t see where the next plate of food was going to come from. How were we going to pay the rent? Were we going to get evicted?" JOHN LYNCH Z 15

- 16. I16 I16 “If any more factories go on Merseyside, they may as well bomb the place.” FRANK BLOOR

- 17. Z 17 Z 17 ANTI-CLOSURE CAMPAIGN T he Committee ran an incredibly proactive defence campaign, adopting a strategic framework that util- ised an extensive external support network. One im- portant ally was GMWU district official Mike Egan, a former Meccano employee who acted as an intermediary between local shop-stewards and the institutional labour movement. Another was Jack Spriggs, a principal protagonist in the 1972 Fisher Bendix work-in. Liverpool Trades Council, meanwhile, administered a fighting fund and activists from Militant and The Socialist Workers Party helped organise a series of direct actions that culminated in a huge anti-dein- dustrialisation rally at the city’s iconic Pier Head.27 Seeking government intervention, the Committee mobilised a powerful cross-party political lobby of approximately 30 MPs, who forced a Parliamentary debate on Meccano’s fu- ture. Meanwhile, workers oversaw a sophisticated PR cam- paign that exposed both the immorality and illegality of the closure announcement. This prompted several industrial correspondents to pen feature articles poignantly describing the human impact of closure. In one, Ross Giles of The Times depicted a customarily moderate breed of worker forced into militant industrial action by malevolent bosses: Mrs Owens and Mrs Hanley seem to have no interest in arrogating management’s right to manage. They just seemed angry at not being consulted and de- termined from now on to have a say in their future. A banner over the entrance proclaims ‘Airfix’ll fix it. They fixed us’.28 A film crew from Thames TV’s Inside Business programme was also invited into the occupied factory. Here, the produ- cer outlines how his fly-on-the-wall documentary scrutinised the behaviour of senior officials:

- 18. I18 Airfix management gave no co-operation at all. We’ve had to pose a number of questions ourselves. Is this all to do with selling the name to some foreign manufacturer? Was equipment bought and never installed? What did happen to X million pounds of government grants? Why were there such high interest rates on loans from the parent company?29 The plight of the workforce penetrated the collective con- science of a British public that considered Meccano an in- tegral part of the nation’s cultural heritage and, moreover, a symbol of industrial survival: I was utterly dismayed to read of the threatened closure of the Meccano factory in Liverpool. Quite apart from the loss of nearly 1,000 jobs in a de- pressed area, the demise of the model engineering system that has entertained and educated millions of boys and men all over the world for three quar- ters of a century can only be described as cata- clysmal … There is only one Meccano: not merely the best toy ever, but part of our national herit- age.30 Such messages provided a tremendous psychological boost to workers: “It made you feel better. It made you feel a bit more positive … At the end of the day, we will have al- ways been supported, no matter what … They just made us feel wanted. Stronger and positive.”31 With the fight for jobs having been thrust into the public arena, the Tory government had little choice but to intervene. Responding to complaints in Parliament from Merseyside MPs David Alton and Eric Ogden, Margaret Thatcher ordered David Mitchell to investigate a possible breach of the Employment Protection Act. Following a meeting with

- 19. Z 19 workers in Whitehall, an outraged Under-Secretary for In- dustry asserted, “It would appear that the management had behaved like a caricature of an 18th century mill owner.”32 After raising the prospect of a staggering £1.5m fine, he de- manded an urgent explanation from company headquarters. "I was fuming. That they could do this without any consultation. No talks, no discussions – just for them to say, “You’re on the dole. Get out." And they expected us to simply walk away … All the women were crying. You could hear screams throughout the factory, when people were getting told: “you’re finished”. They were crying and hugging each other." FRANK BLOOR

- 22. I22 AIRFIX STRIKES BACK C ompany chairman Ralph Ehrmann would now scramble into action. At private talks with Mitchell, he sought an exemption from his legal obligations as an employer, claiming management was forced to expedite closure due to huge financial losses. The DTI official rejected his assertion and forced him to accept a formal request for the anti-closure campaign to be included in the 90-day stat- utory period of redundancy. Notwithstanding this minor con- cession, there would be no political solution. As acolytes of free market capitalism, the new Tory government had already aligned itself with corporate agendas.33 By rejecting a final plea from the unions for a cash bailout, they effectively en- dorsed closure. Emboldened by Whitehall’s apathy, company bosses would now act with impunity. On Christmas Eve, they sought to freeze the occupiers out by switching-off power, gas and water. Head office then intercepted public donations and withheld statutory holiday pay in a bid to starve employees into submission. The assault would continue when Airfix hired PR consultant Nick Cowan to denigrate employees in the press. Described by the unions as ‘a paid assassin’, he sought to tap into popular misperceptions of Liverpool’s in- dustrial relations culture: “My argument is that Meccano had become un- manageable because of vandalism, sabotage and pilfering over many years. I told the unions, if you agree with us that there are special circumstances, our allegations of industrial anarchy will not be re- leased to the press. If we go out in public and spread this mess around it won’t do the reputation of Merseyside any good.”34

- 23. Z 23 Furious Committee leaders dispelled these perfidious and potentially harmful accusations in a rebuttal published in The Sunday Times. The article included counterclaims of “ex- cessive management perks – lobsters and curtains bought on petty cash”, and featured the testimony of former Mec- cano boss George Flynn: He told us that in times of stress he had never worked with a better workforce. “God knows what possessed Airfix to say the things it did about them. The stewards were more committed to get- ting Meccano right than some of the managers.” He claims that disputes were few and that the company’s problems were not its workforce but wrong investment at the wrong time.35 “Airfix’ll fix it. They fixed us.”

- 24. I24 SUPER SELL CAMPAIGN F or the remainder of the occupation, Committee lead- ers desperately sought third party investment. They initially turned to local Councillor Derek Hatton, who sponsored a resolution calling for the City of Liverpool to fin- ance a workers’ co-operative. The highly controversial left- wing firebrand outlined his municipal takeover proposal in The Militant: “Under this reactionary Tory government we’re putting forward the proposal that the local author- ity take over the Meccano plant as a municipal en- terprise, in a similar way that local authorities take on direct building work etc. I think the city council have got to take this issue on board … to ensure that the necessary money is pumped into Mec- cano to enable workers to take it on, to manage it and to control it along with the trade unions con- cerned.”36

- 25. Z 25 When the plan fell victim to Liverpool’s fragmented political landscape, Committee leaders once again turned to the in- stitutional labour movement. Working alongside trade union officials, they undertook a feasibility study that resulted in a new survival blueprint.37 Ehrmann, meanwhile, was per- suaded to join a joint working party devised to negotiate a sale. A ‘super sell’ campaign was launched with the sole ob- jective of finding a buyer before 28 February 1980, the deadline for the government-enforced consultation period. With shop-stewards presenting their proposals to interested parties, hopeful sit-inners cleaned the factory from top to bottom and performed vital maintenance of machinery. However, a sale failed to materialise. Ehrmann only ever gave a cursory glance at several formal enquiries and two cash offers. The working party experiment was merely ma- nagerial subterfuge, a red herring devised to give the im- pression of full and meaningful consultation as Airfix deliber- ately ran down the clock.38 It slowly dawned on the workers and their supporters that Ehrmann had absolutely no inten- tion of selling the rights to Meccano: “There is a growing suspicion that he wants to take the brand names away from Liverpool and, pos- sibly, have them manufactured in factories abroad. If that turns out to be the case, it would be tan- tamount to stealing names which have been de- veloped in the City of Liverpool.”39 With negotiations stalling, an irrevocable malaise took hold of a battle-weary workforce: “It was absolutely freezing cold. You know, a cold and empty factory. You’re looking at places and say- ing, “Oh, Mary used to sit there.” It was like a ghost town. You’re looking for people, you know what I mean? We just called it a day and that was it.”40 Management thereby targeted vulnerable employees with head turning compensation packages. As high-level talks

- 26. I26 continued, financial self-interest superseded the abstract values of fraternal solidarity, kinship and community - prompting individual workers to take voluntary redundancy: “We were all in the fighting spirit when it first happened, and we weren’t going to give up for anybody. But the way they did things and threatened us … “You’re not going to get your re- dundancy.” … People were really struggling … A job came up at a solicitor’s and luckily enough I got it. I was still in touch with people. I’d ask, “How are you going?” … They’d say, “There’s no-one going now. So we packed it in.””41 Resistance crumbled and, with the 90-day deadline having passed, the occupying force dwindled to 50. Enraged by Airfix’s refusal to accommodate a sale, Commit- tee leaders and their union representatives threatened a re- peat of the violence witnessed at Grunwick three years prior. When company headquarters obtained a High Court repos- session order for the plant, the remaining occupiers rein- forced the barricades, with some taking vantage points on the roof.42 A final show down seemed inevitable. However, having sought legal advice, union leaders urged their mem- bers to abandon the factory. After some consideration, the Committee eventually relented - drawing up plans for a peaceful and dignified withdrawal on their own terms. But they wouldn’t be afforded such an opportunity. At 4am on the morning of 11 March 1980, bailiffs backed by 36 police- men smashed through the barriers and stormed the premises. This predawn raid, conducted by what shop- stewards dubbed ‘the job-killer squad’, took dazed and con- fused workers by surprise. By the time a picket was re-es- tablished outside, locksmiths had secured the building. After 102 days, the Meccano sit-in was finally over.

- 27. Z 27 THE OCCUPATION IN RETROSPECT A lthough the fight for jobs was halted in March 1980, the occupation united a regional labour movement that had become fragmented and demoralised by the May 1979 election defeat. As a beacon of resistance that inspired a new wave of mass defiance against the evils of Thatcherism, it had a clear political afterlife. Despite such intense symbolic significance, the battle for Meccano has been disregarded by contemporary labour historians, who have instead cast their scholarly gaze elsewhere. Mirroring this literary marginalisation, the anti-closure struggle has failed to penetrate Liverpudlians’ collective memory. Today, younger generations are seemingly unaware of the events that unfolded four decades ago. The sit-in, nevertheless, signifies a remarkable chapter in Britain’s illustrious labour history. Whilst to some, it may rep- resent yet another glorious defeat for the trade union move- ment, to those who participated, it exemplifies the spirit of Liverpool – the city that dared to fight: “My take on it? At least we had enough pride and dignity in ourselves to do it. We didn’t just say, “Well, you’ve sacked us with 15 minutes notice on a Friday … Oh, isn’t that awful? Look at us, aren’t we badly done to?” We didn’t just take it on the chin and walk away. We put up … Ultimately, we were never going to win, but at least we had a go. Every single one of us – we’ve all still got pride in ourselves. At least we tried. That counts for some- thing.”43

- 28. I28 Following the permanent closure of the Binns Road plant, 12-year-old John Singo, whose mother was one of the 950 workers who lost their livelihoods, penned the following threnody: It was Friday afternoon When the news was broke so soon The Meccano machines had stopped And all the workers they had flopped The place has been going for donkey’s years And now all the workers were in floods of tears It was in the papers and on the telly That all the workers had got the welly All the staff, they started a sit-in Hoping that they wouldn’t be beaten “Airfix fixed us, so we’ll fix them” All the workers chanted again Some of the workers knew they wouldn’t win To be out of work, it was a sin Now they’re collecting redundancy pay To all the workers, it was a miserable day No more Meccano for anyone Those boring days have yet to come The sit-in is over and no Meccano no more How I loved the toys they made And now it is completely a bore

- 29. Z 29

- 30. I30 I30 1. Local shop steward Ted Mooney has produced a detailed overview of the aborted sit-in, see Ted Mooney, Workers’ con- trol and workers’ management: work in the unions, Liverpool, self-published, 2018. 2. For an eyewitness account of the Fisher-Bendix dispute, see Mark Fore, Under new management? The Fisher-Bendix occu- pation, London, Solidarity, 1972. 3. Brian Marren, We shall not be moved: How Liverpool’s working class fought redundancies, closures and cuts in the age of Thatcher, Manchester, Manchester University Press, p. 257. 4. Alongside Marren, Stephen Mustchin has provided a fascinat- ing study of the 1984 occupation of Cammell Laird, see ‘From workplace occupation to mass imprisonment: The 1984 strike as Cammell Laird Shipbuilders’, Historical Studies in Industrial Relations, 31/32 (2011), pp.31-61. Meanwhile, the 1995-98 dock strike is also outlined in Pauline Bradley and Chris Knight, Another world is possible: How the Liverpool dockers launched a global movement, London, Radical Anthropology Group, 2004. 5. The Socialist Challenge, 6 December 1979. 6. Kenneth D. Brown, ‘Death of a Dinosaur: Meccano of Liver- pool, 1908-79’, Business Archives Sources and History, 66 (1996), p. 26. For a more detailed account of Meccano’s com- mercial history from the same author, see Factory of dreams: A history of Meccano Ltd., Lancaster, Crucible, 2007. 7. The Guardian, 22 January 1980. 8. Oral testimony from L. Hanrahan, recorded 17 February 2021. 9. Oral testimony from G. Shepherd, recorded 26 April 2021. 10. The Times, 6 February 1980. 11. Oral testimony from F. Bloor, recorded 13 December 2020. 12. Oral testimony from J. Lynch, recorded 8 October 2020. 13. Oral testimony from P. Gerdes, recorded 2 May 2021. 14. Oral testimony from F. Bloor, recorded 13 December 2020. 15. Oral testimony from J. Lynch, recorded 8 October 2020. 16. Oral testimony from G. Shepherd, recorded 26 April 2021. 17. Oral testimony from F. Bloor, recorded 13 December 2020. 18. Ibid. 19. The Socialist Challenge, 6 December 1979. 20. Oral testimony from P. Gerdes, recorded 2 May 2021. 21. Ibid. 22. Oral testimony from F. Bloor, recorded 13 December 2020.

- 31. Z 31 Z 31 23. The Times, 6 February 1980. 24. Oral testimony from G. Shepherd, recorded 26 April 2021. 25. The Liverpool Echo, 18 January 1980. 26. Oral testimony from P. Gerdes, recorded 2 May 2021. 27. Additional protests included flying pickets at Airfix facilities and a sit-down vigil at company headquarters in London. Aware of the importance of acts of fraternal solidarity, shop stewards joined a protest for union recognition organised by migrant workers at the Chix sweet factory in Slough. 28. The Times, 6 February 1980. 29. The Sunday Times, 13 January 1980. 30. The Guardian, 7 December 1979. 31. Oral testimony from P. Gerdes, recorded 2 May 2021. 32. The Times, 13 December 1979. 33. Months earlier, Ehrmann’s Clabir Corporation had signed a government-sponsored deal to invest in a MOD contractor in Hertfordshire. 34. The Sunday Times, 13 January 1980. 35. Ibid. 36. The Militant, 14 December 1979. 37. The plan entailed a drastic reduction in operations and a skel- eton workforce of 200. 38. Ehrmann’s asking price was said to be £5.6m, but the unions estimated the book value of Meccano was nearer £1.2m. 39. The Liverpool Echo, 12 February 1980. 40. Oral testimony from P. Gerdes, recorded 2 May 2021. 41. Ibid. 42. Outside the factory gates, a 200-strong crowd held success- ive daylong vigils. A mass picket was assembled, comprising of fireman, dockers, shore gangs, shipbuilders and workers from the nearby Massey Ferguson plant. 43. Oral testimony from T. Culligan, recorded 7 February 2021.

- 32. “Don't waste any time mourning. Organise!” JOE HILL, LABOUR ACTIVIST AND SONGWRITER