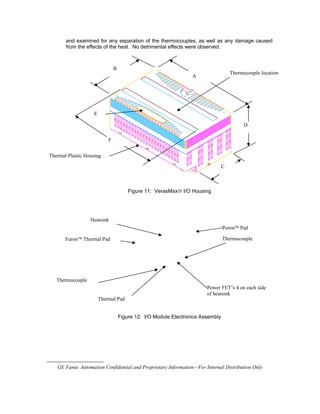

This document discusses using thermally conductive plastic housings for industrial control electronics like PLCs and power supplies. Finite element modeling and testing of materials from different suppliers found that a prototype material from GEP performed better than other options at dissipating heat. Samples of housings molded from the GEP material showed lower steady-state temperature readings when tested with instrumented I/O modules, verifying its improved thermal conductivity over conventional plastics. Further verification is still needed using a housing designed specifically for the GEP material.