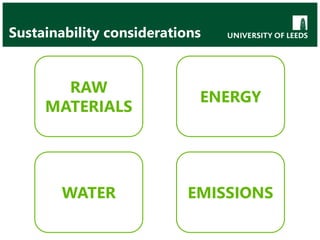

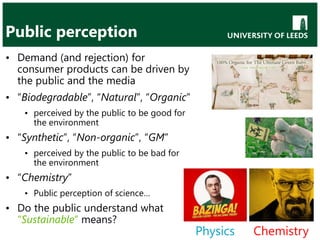

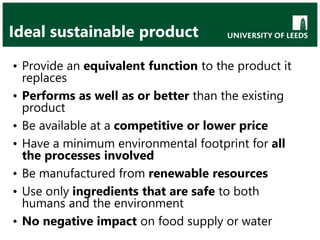

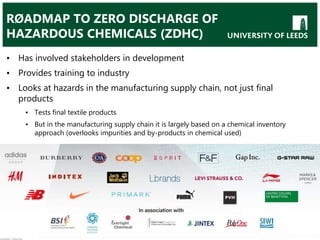

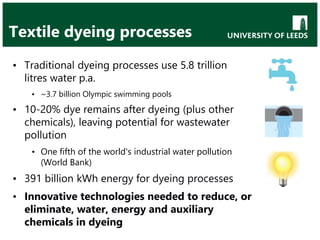

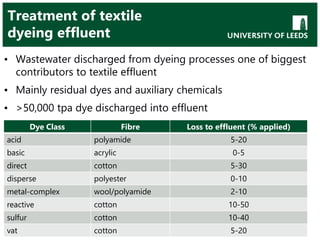

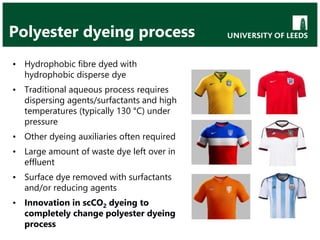

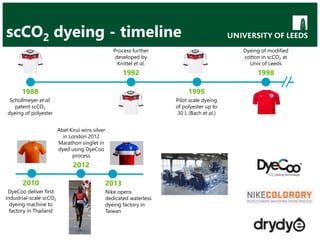

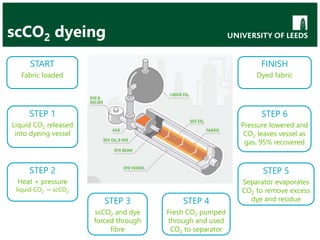

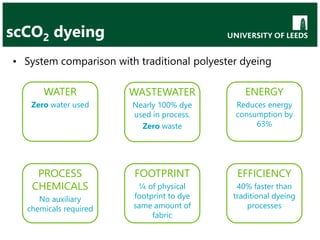

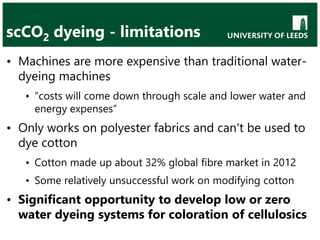

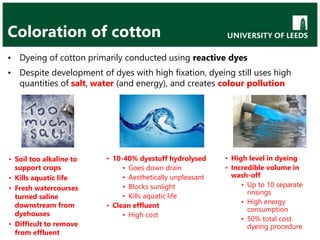

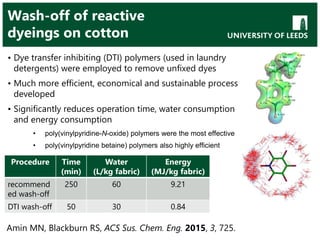

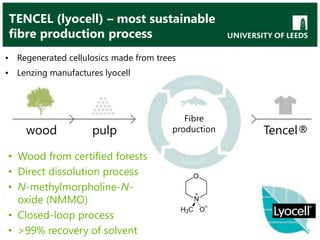

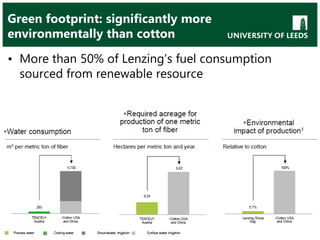

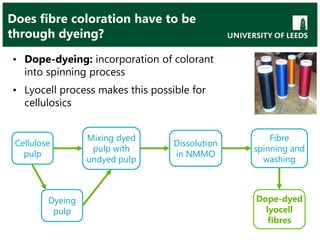

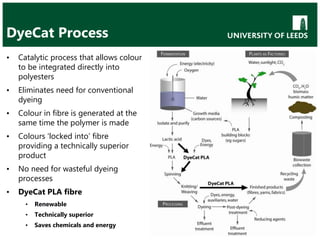

This document discusses the sustainability challenges facing the textile and dyeing industries and opportunities for innovation to address these challenges. It notes that the world's population is expected to rise significantly by 2050, increasing demand for resources and chemicals and their environmental impacts. Synthetic fibers like nylon and polyester have improved quality of life but are non-degradable and rely on non-renewable resources. The document examines various fiber production processes and textile dyeing techniques, identifying ways to make them more sustainable by reducing water and energy usage and hazardous chemicals. It also explores alternatives to conventional cotton production and processing.