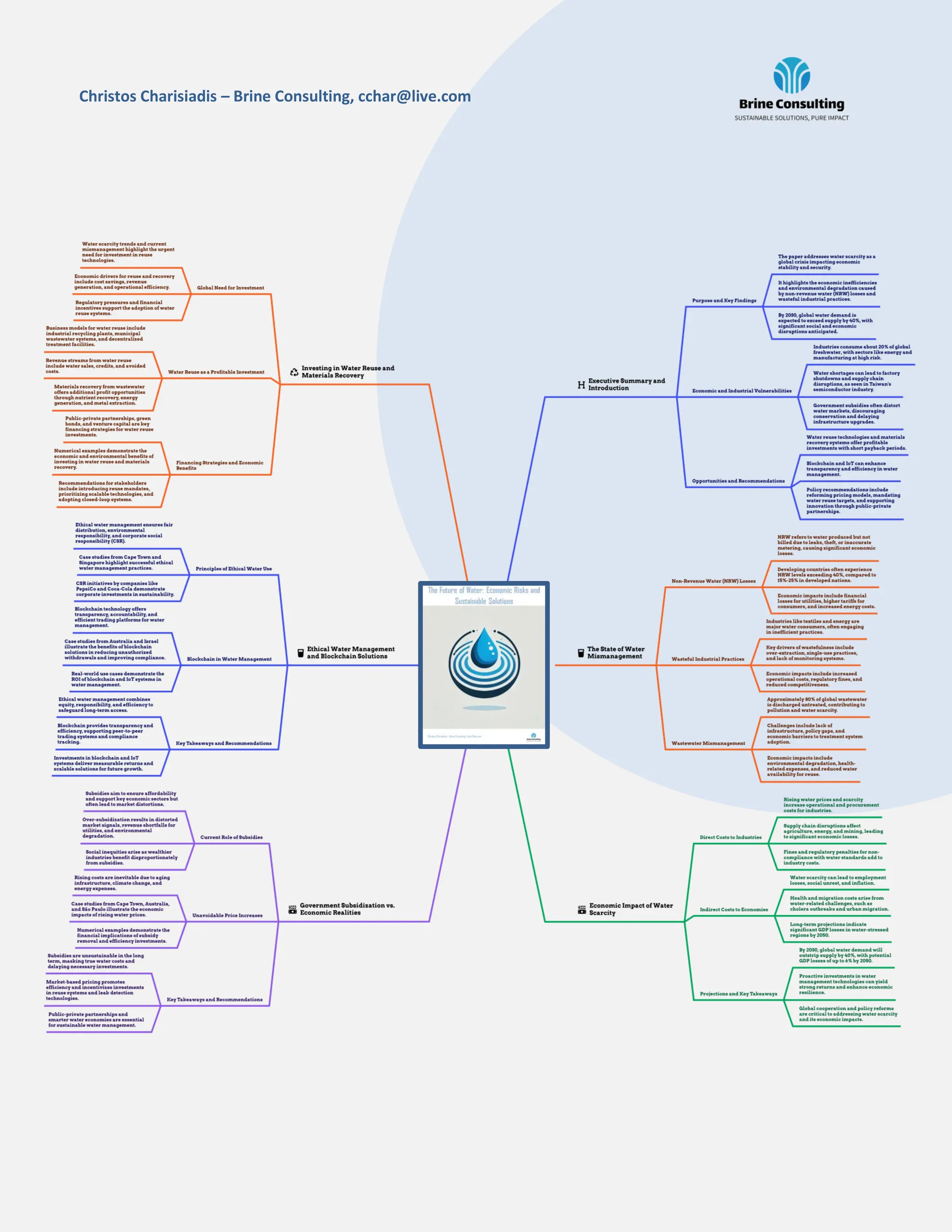

The document highlights the urgent need for sustainable water management due to increasing water scarcity and mismanagement, which threaten economic stability and social well-being. It presents various strategies for industries, governments, and investors to implement sustainable solutions through innovative technologies, regulatory reforms, and ethical frameworks, arguing that addressing water issues can lead to economic growth and resilience. Key findings indicate that proactive investments in water reuse and efficient practices can prevent significant economic losses and ensure equitable access to water resources.