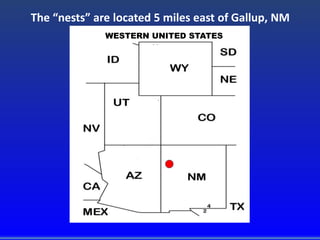

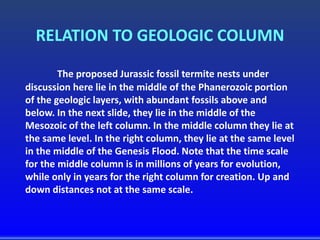

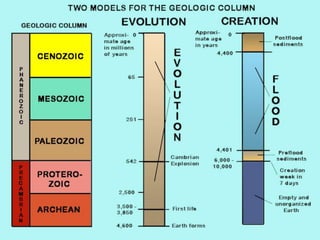

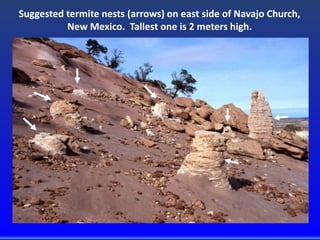

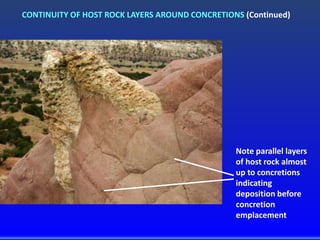

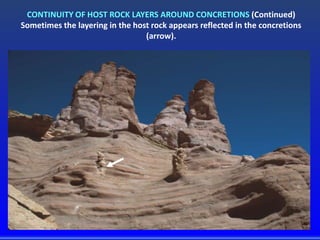

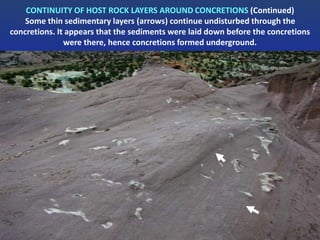

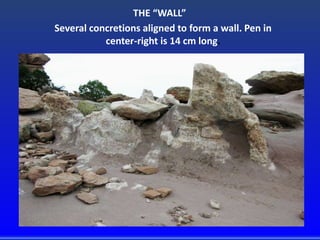

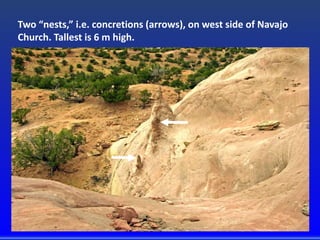

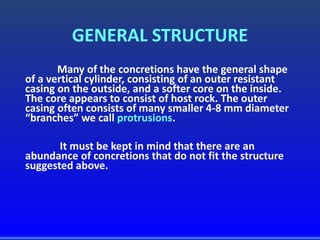

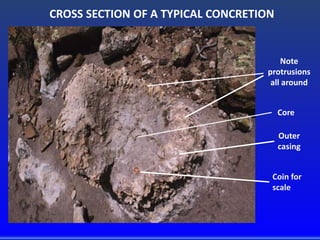

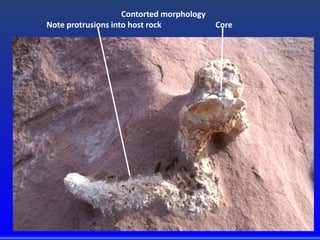

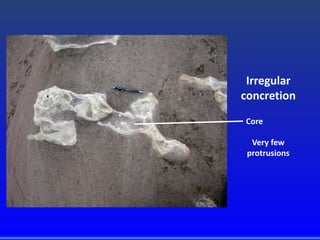

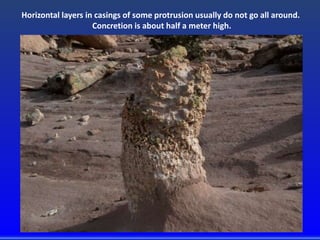

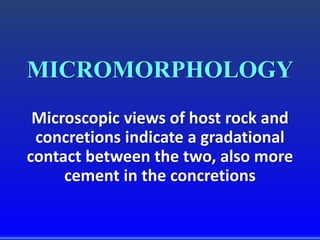

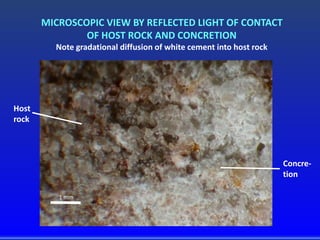

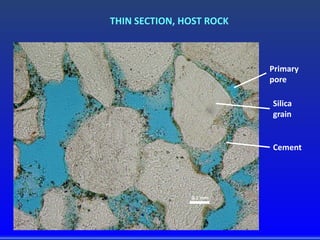

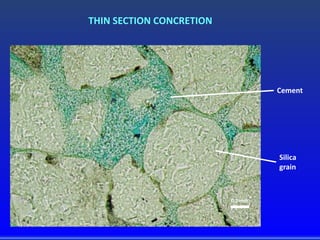

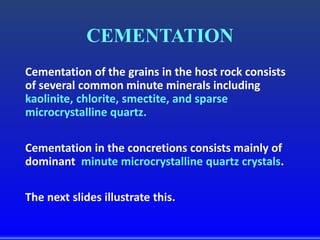

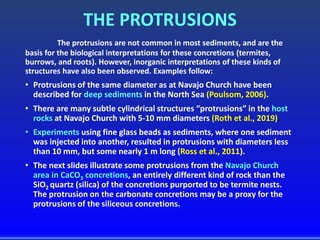

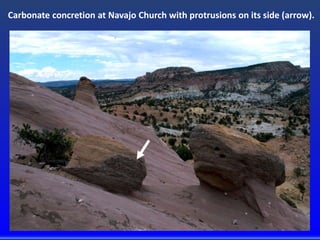

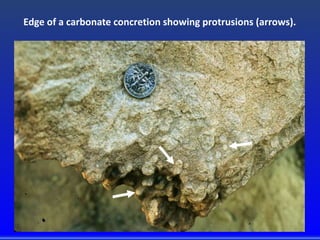

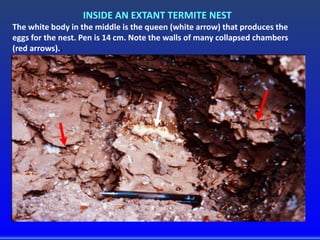

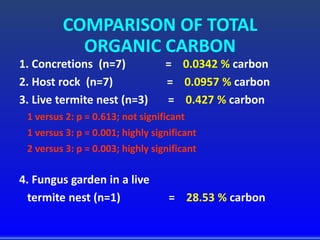

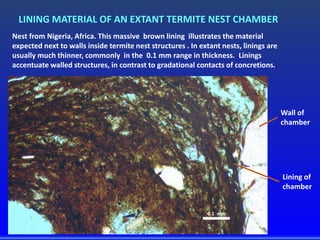

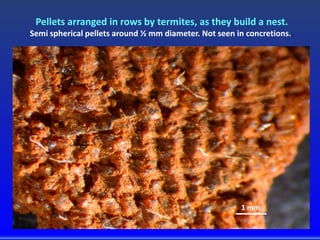

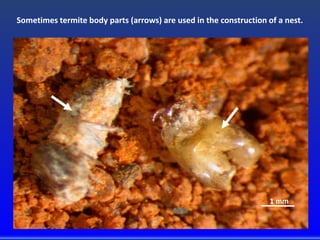

The document discusses controversial fossil termite nests found in the Jurassic Morrison Formation in New Mexico. While some see this as evidence challenging a biblical timeframe, others question whether they are truly termite nests. The structures, called concretions, appear to have formed underground after sediment layers were deposited, rather than growing epigenously. They have a core of host rock surrounded by an outer casing of protrusions made of different material than the surrounding rock. While some claim these provide evidence for slow evolutionary timescales, others argue their formation could be explained without requiring millions of years.

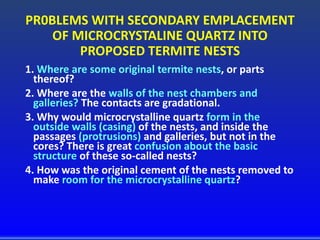

![2. Collapse of a concretion

Figure 5B © in the research report on this study in the journal

Sedimentary Geology [392 (2019) 105526], illustrates what appears to be

a collapsed concretion. The figure below is a general representation of

that figure.

This is a cross-section of a medium-sized concretion. Note the apparent

drift of the insides towards the upper side as indicated by the orientation

of the protrusions, and suggests soft sediment movement.

Casing of

concretion

Protrusion

S-shaped

protrusion

10 cm](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/termites2022-230320073425-d6747ccb/85/FOSSIL-TERMITES-74-320.jpg)

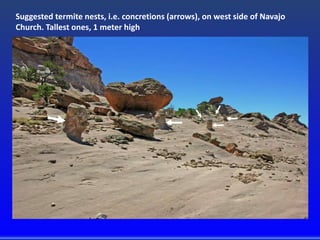

![Hasiotis’ personal communication

to Roth, July 1, 2007

Agrees that mounds are not “fulgurites nor rhizoconcretions.”

Suggests are termite nests later replaced hydrothermally.

Found organic balls. [SEM by Roth shows random fungus

common]

The area of the nests is in the path of “uranium roll fronts and

other hydrological and hydrothermal activities.”

Suggests igneous activity following termite nests formation

resulting in present structures at Navajo Church.

Body fossils of termites and other social insects are rare to begin

with. This is underplayed by the opposing view.

“Please let’s keep in touch and maybe collaborate on some of

these structures to look at the cement histories in detail.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/termites2022-230320073425-d6747ccb/85/FOSSIL-TERMITES-92-320.jpg)