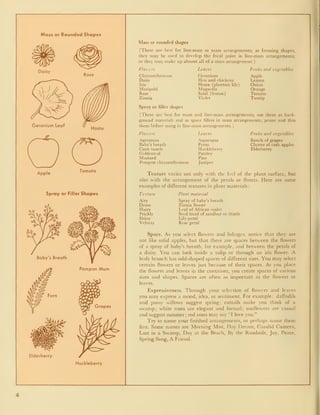

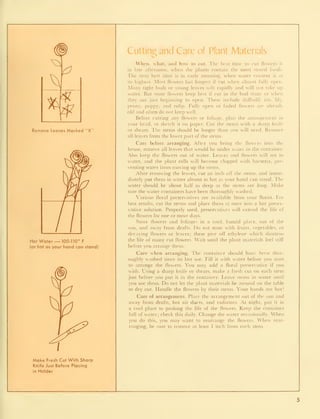

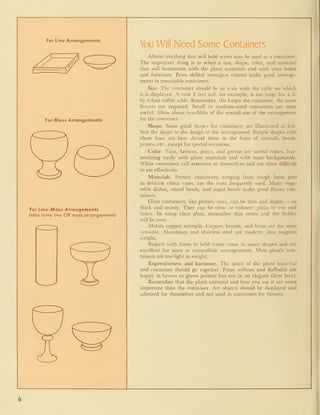

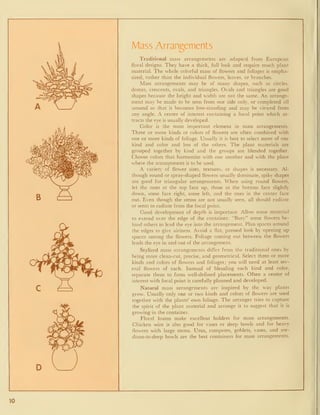

The document is a comprehensive guide on flower arranging, detailing techniques for selecting and caring for plant materials, as well as principles of design. It discusses the importance of color, shape, size, and expressiveness in creating aesthetically pleasing arrangements and emphasizes the value of creativity in the process. Additionally, it provides practical advice on tools, container selection, and arrangement styles to help both beginners and experienced arrangers enhance their skills.