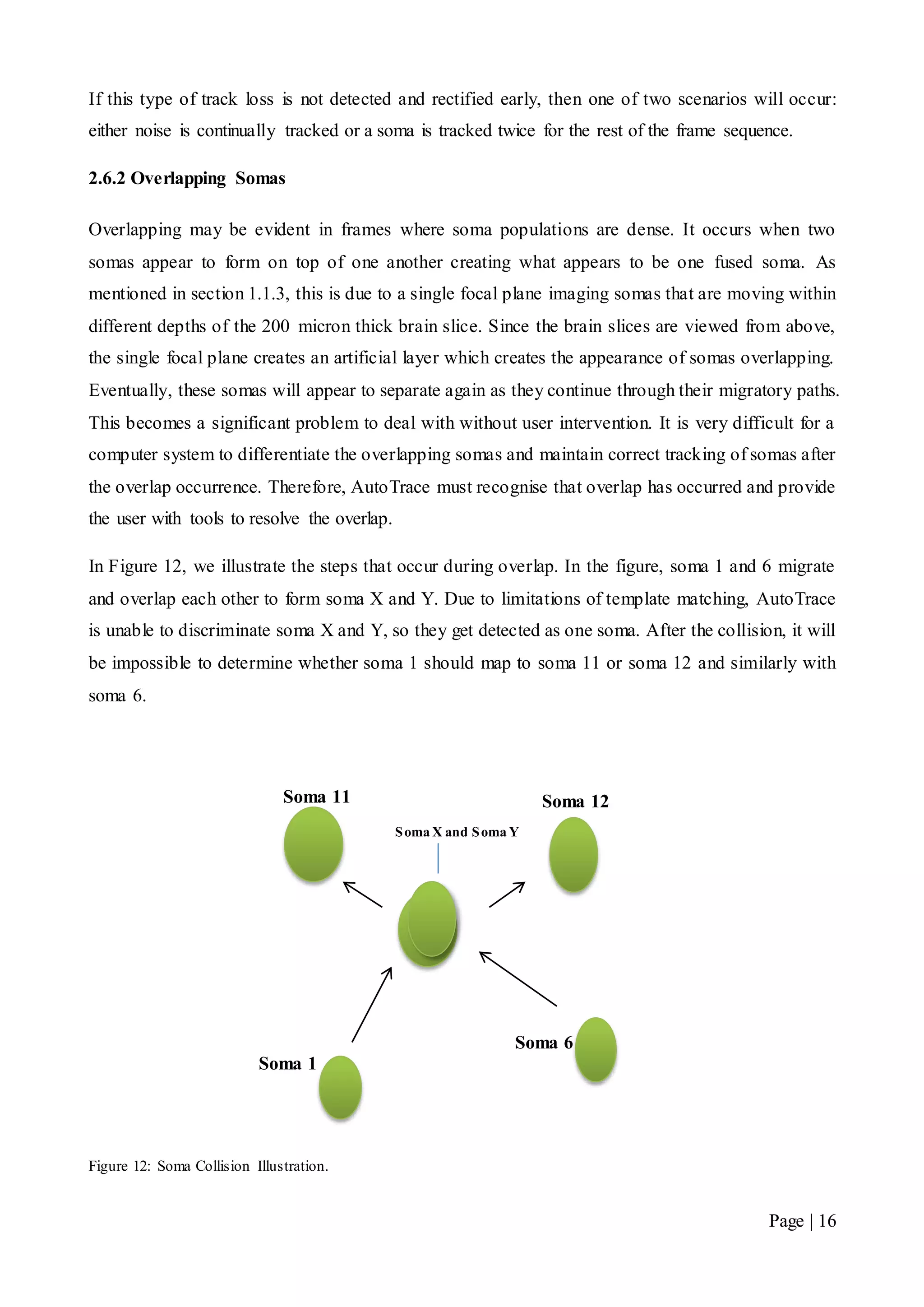

This document describes a final year electrical engineering project to develop an automated neuron tracking system called AutoTrace. It aims to track the migration paths of neurons in time-lapse microscopy images to assist neuroscientists. The system uses template matching and nearest neighbour algorithms to locate neurons across frames and construct migration paths. Testing established the accuracy of the algorithms and balanced accuracy against false positives. The system shows potential to save significant time over manual tracking.

![Page | 2

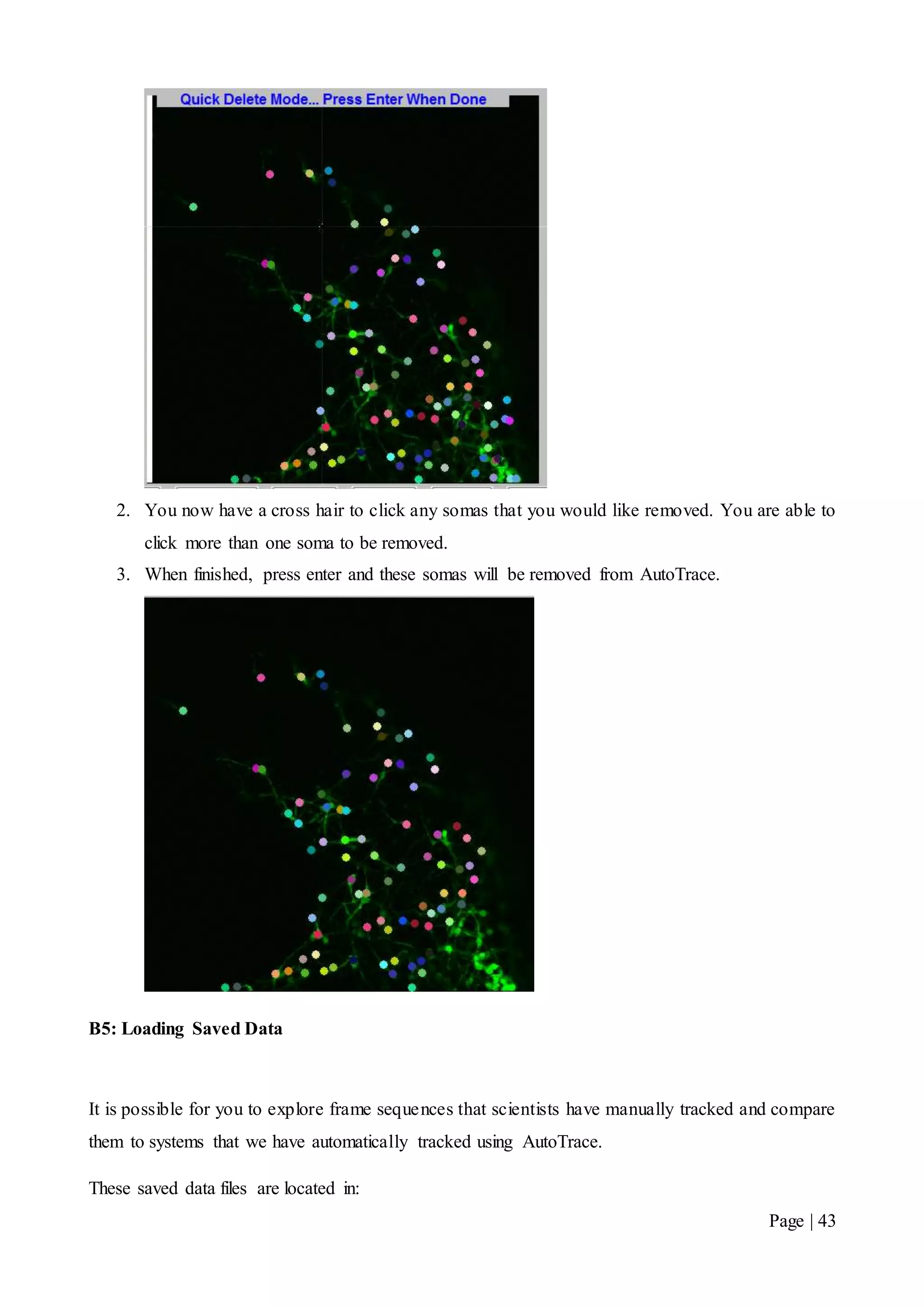

neuron and has the responsibility of maintaining the cell functionality. The growth cone explores

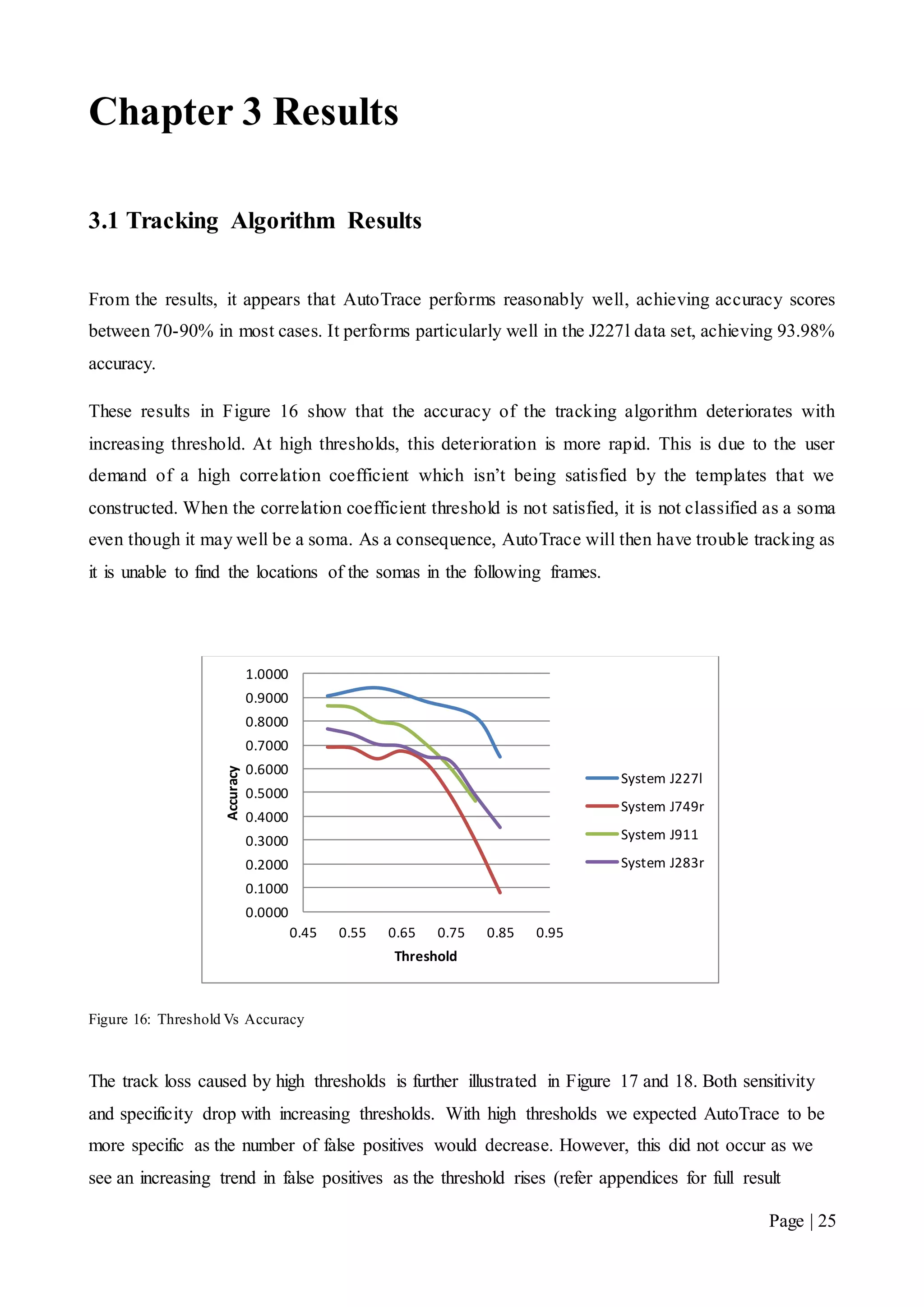

the cellular environment, determining the direction of growth and guides the axon to that direction.

The axon is a fibre that joins the soma to the growth cone and carries the neural signals. The

dendrites’ function is to pick up impulses from other cells. Some neurons develop very few

dendrites at birth whilst others develop very extensive dendritic trees [1].

Neuroscientists are interested in a special kind of neuron cell that forms in the developing stages of

the embryonic brain. During embryonic development the brain emerges from the neural tube, an

early embryonic structure. The most anterior part of the neural tube is called the telencephalon,

which expands rapidly due to cell proliferation, and eventually gives rise to the brain. Gradually

some of the stem cells differentiate into neurons and glial cells, which are the main cellular

components of the brain. The newly generated neurons are referred to as ‘immature neurons’ or

‘developing neurons’. These neurons differ from mature neurons because they are able migrate

from their birthplace in the embryonic brain to their final resting positions, at which point synapses

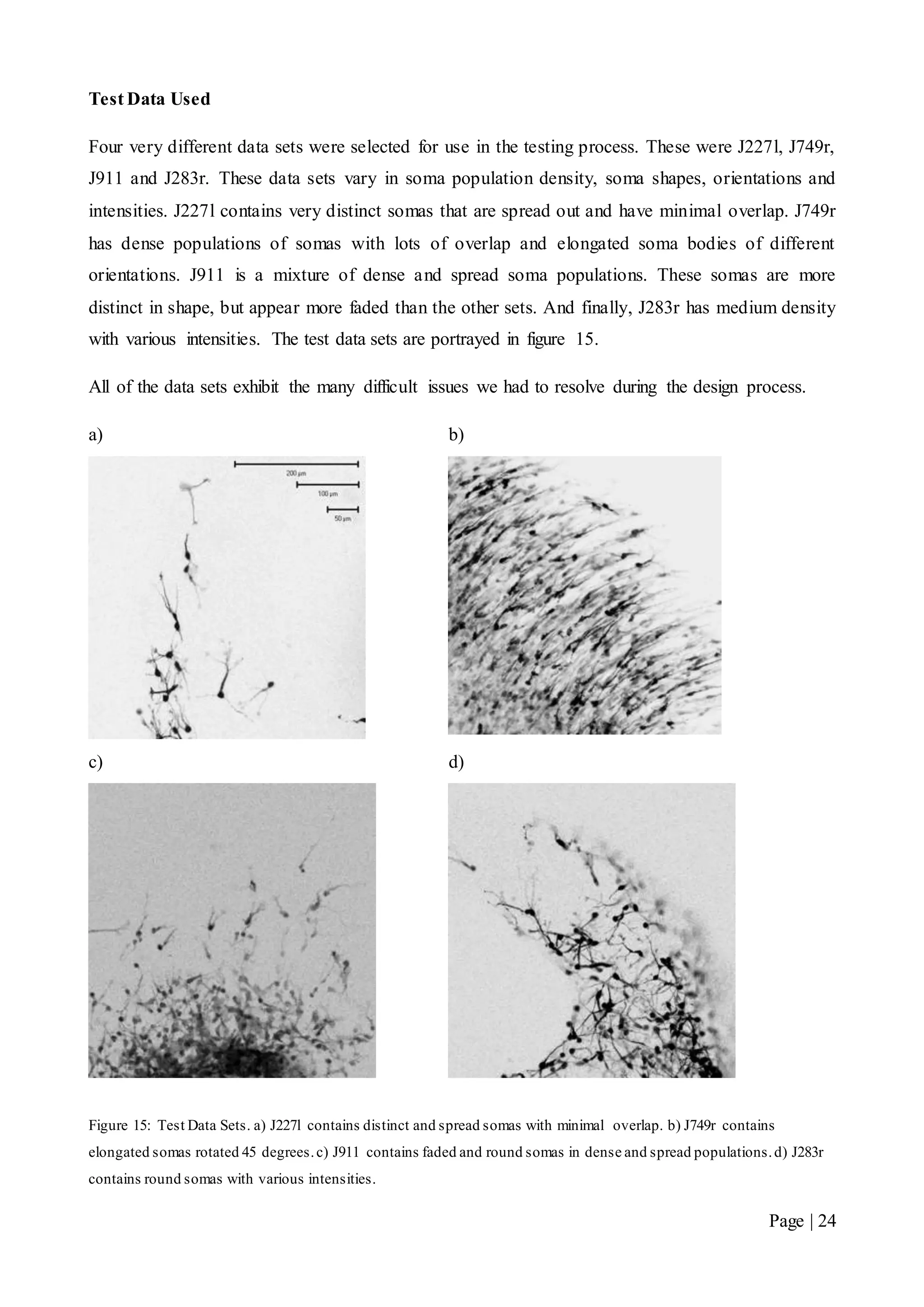

with other neurons are formed. Synaptic communication between neurons leads to the

establishment of functional neural circuits that mediate sensory and motor processing, and underlie

behaviour [1].

Immature neurons share similar features with the typical neuron structure, namely, the axon and the

dendrites (see Figure 1). However, these two features can be difficult to differentiate during

development, especially of cells in culture, and are instead collectively referred to as ‘neurites’. A

neurite refers to any branch or projection from the main cell body (soma) of a neuron. An additional

feature found in immature neurons is the Micro Tubule Organising Centre of the neuron (MTOC).

The MTOC provides structural support for the neuron as well as assisting in cellular transport (see

Figure 2).

1.1.2 Neuron Migration and Disorders

In the developing brain, immature neurons must migrate from the areas where they are born to the

areas where they will settle into their proper neural circuits. Neuronal migration is the method by

which neurons travel.

Migration is a dynamic process in which a cell searches the environment and translates

acquired information into somal advancement. In particular, interneuron migration during

development is accomplished by two distinct processes: the extension of neurites tipped

with growth cones; and nucleus translocation, termed nucleokinesis. Migration is a key

component of cortical development as neuronal progenitors arise in locations distal to where

the fully differentiated neurons reside. [2]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-9-2048.jpg)

![Page | 3

Neuronal migration disorders (NMDs) are a group of developmental brain disorders caused by the

defective movement of neurons in the developing brain and nervous system. Neuronal migration is

controlled by a complex assortment of chemical guides and signals [3]. Abnormal signals result in

neurons not ending up where they belong. This can result in structurally abnormal or missing areas

of the brain in the cerebral hemispheres, cerebellum, brainstem, or hippocampus. As a result of

abnormal migration, affected individuals typically display mental retardation and epilepsy.

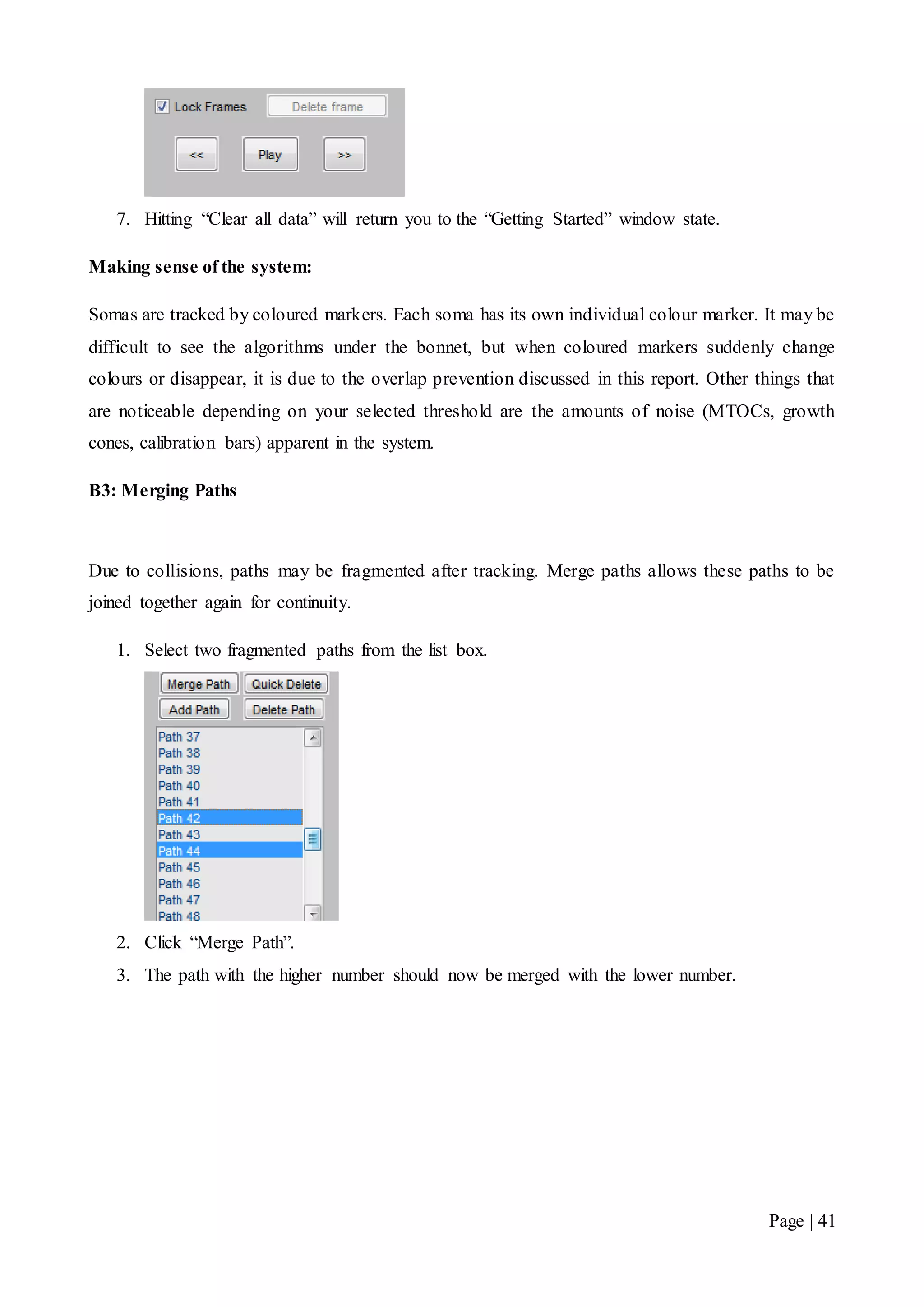

Although patients with the more severe forms of NMDs often present during infancy, patients may

present at any age from newborn to adulthood. Symptoms vary according to the abnormality, but

often result in poor muscle tone and motor function, seizures, developmental delays and mental

retardation [4].

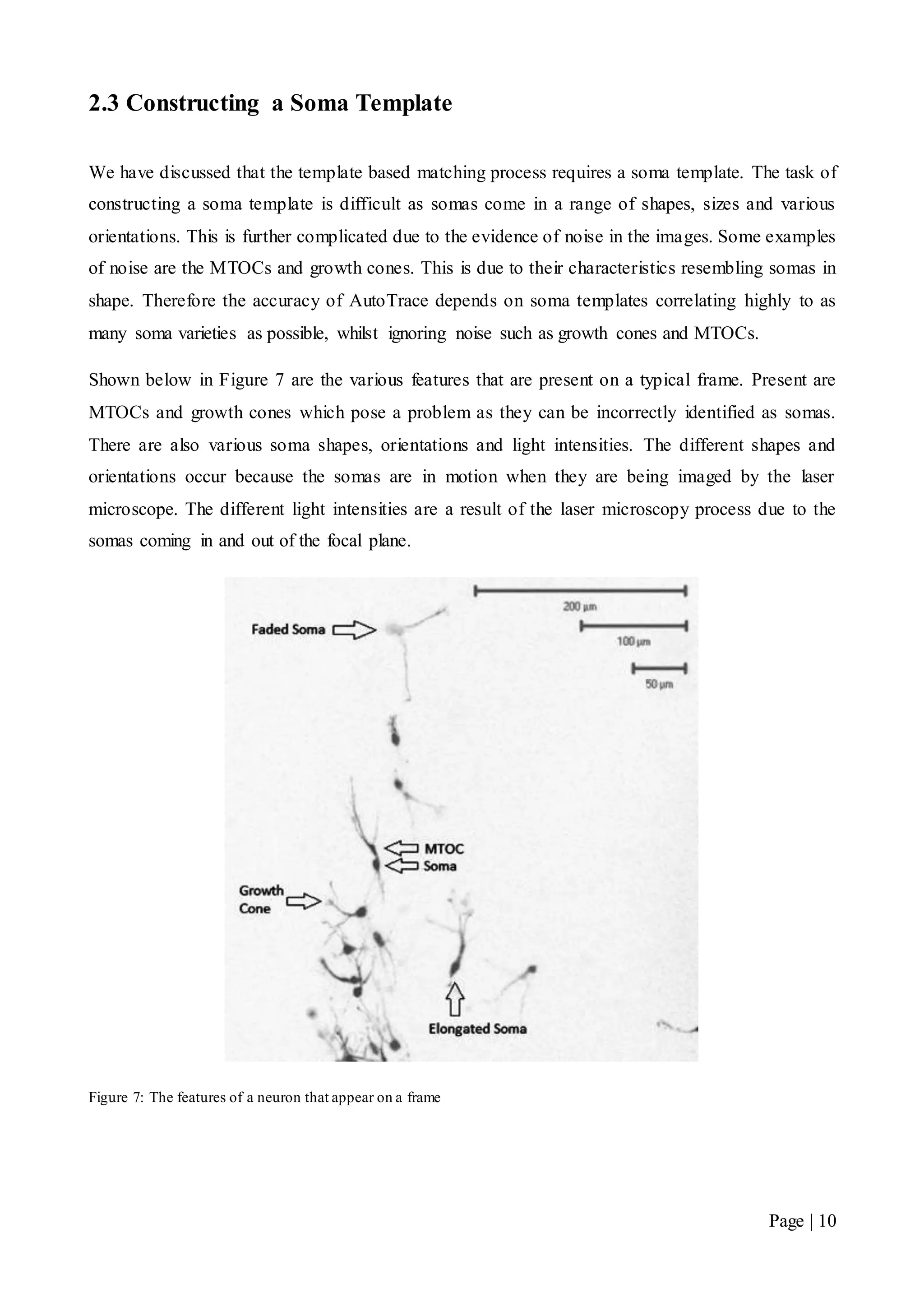

1.1.3 The Imaging Process

To obtain images of neuron migration, neuroscientists at the Howard Florey Institute first

genetically modify the neuron cells of mice with a fluorescent protein. Scientists then take a brain

slice, around 200 microns thick, of the genetically modified mice and place the slice in a culture. It

is here where the neuron motions are imaged using laser microscopy. Images are taken at 5 minute

intervals over a period of three to twenty-four hours. Images are taken using a single focal plane.

This narrow single focal plane within the 200 micron thick slice causes artificial layering in the

imaging of these neurons. The appearance of faded neurons and neurons disappearing/reappearing

is due to neuron movement within the 200 micron thick slice resulting in movement in and out of

the focal plane. It is important to note that these images vary in clarity and soma: shape, orientation,

size and densities, which are dependent on the particular culture. An example of one image is

shown in Figure 3 and an example an imaged neuron cell is shown in Figure 2 with the soma width

being roughly 10 microns wide and neurites 1 to 10 microns wide.

Figure 2: An image of a typical immature neuron. The soma can be found in the bottomright corner roughly 10 microns

wide; an MTOC found immediately above the soma is similar in appearance but slightly smaller; neurites which

protrude from the MTOC and Soma vary from 1 to 10 microns in width; a growth cone at the tip of the neurite branch is

found the top right corner.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-10-2048.jpg)

![Page | 4

Figure 3: An image of immature neurons found in the embryonic brain of mice

It must be noted that technically the brain slice is neither living nor dead biologically speaking.

Although eventually, neurons within the brain slice will die, their presence in a culture facilitates

migration for a period of many hours.

Once the images have been taken, they are sequenced together frame by frame to produce a moving

image. Scientists then view the sets of images via computer software and begin the time consuming

task of manually tracking somas. With modern day technology, these frame sequences are growing

to the order of hundreds, further increasing the time required. It goes without saying that an

automated cell tracking software to automate this process would be of great benefit to scientists. We

will now consider current cell tracking software in the following section.

1.2 Review of Existing Cell Tracking Software

The alternative to manually tracking cells is to use an automated cell tracking software package.

However, as we will explain, the current cell tracking software is inadequate in tracking immature

neurons found in the datasets we are dealing with. Let’s consider the following software candidates:

CellTrack by Ohio State University, United States of America [5].

TrackAssist by National ICT Australia (NICTA) [6].

High Content Analysis (HCA) Vision by The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial

Research Organisation (CSIRO) [7].

These software packages represent what is available for use by scientists today. ‘Previous

automated cell tracking methods developed so far, mainly focus on association of cells across](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-11-2048.jpg)

![Page | 5

frames and do not provide a sensitive tracking of the cell as it deforms during its migration’ [5].

Let us detail each software package and give reasons for their unsuitability.

1.2.1 CellTrack

CellTrack is a free open source software package developed by the Department of Computer

Science and Engineering at The Ohio State University, USA. It relies on an edge-based detection

mechanism to detect cell bodies in an image. This edge-based tracking method is based on snakes

[8] and ‘relies on a new energy functional that can accurately track changes in the shape of a

moving cell’ [5]. Without going into the technical details, CellTrack primarily makes use of

contours of cellular shapes. CellTrack is inadequate in our circumstance because it only deals with

cell images that have distinct cell wall boundaries with no protruding branches. As discussed in

section 1.1.3 and shown in Figure 2, the immature neurons we are dealing with have various

neurites attached to the main cell body. These neurites vary in shape, length and thickness as well

as changing in form while the neuron migrates through the brain. As such, CellTrack is unable to

locate and track somas we are interested in.

1.2.2 TrackAssist

TrackAssist by the National Information and Communication Technology Australia is also an edge-

based tracking software but differs from CellTrack by instead using Roberts Edge Detection

scheme [9]. This scheme performs a two-dimensional spatial gradient measurement on an image

and highlights regions of high spatial frequency. However this scheme is also based on cell

boundaries being clearly distinct and without the presence of branches, thus unsuitable for detecting

immature neurons.

1.2.3 HCA Vision

Finally we consider CSIRO’s HCA-Vision. HCA-Vision is a proprietary and closed sourced cell

detection software package. Although it lacks the ability to track cells through frame sequences, it

is very powerful in the detection of somas and neurite branches. However, HCA-Vision is only

accessible if exorbitant licensing fees in the order of $4000.00 AUD are paid. With the addition of

being closed source, HCA-Vision is non-extendible to our tracking problem and is considered

inaccessible for use at the Howard Florey Institute. Therefore, our motivation is to build an

automated tracking program that is able to meet the demands of tracking immature neuron cells as

well as being inexpensive.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-12-2048.jpg)

![Page | 7

Chapter 2 Design and Development

2.1 Convolution in Imaging

Convolution is a widely used technique in image and signal processing. The two dimensional

convolution is similar to the one dimensional case except there is no flipping procedure of the filter

matrix, and both vertical and horizontal rows of the matrix are evident in the multiplication. Each

output of the discrete convolution can be calculated by the following equation:

𝑦[ 𝑚, 𝑛] = 𝑥[ 𝑚, 𝑛] ∗ ℎ[ 𝑚, 𝑛] = ∑ ∑ 𝑥[ 𝑖, 𝑗]ℎ[ 𝑚 − 𝑖, 𝑛 − 𝑗]

𝑘

𝑖=−𝑘

𝑘

𝑗=−𝑘

This process is better visualised as taking a template matrix h, overlaying it on top of the original

image x and then multiplying and summing where overlap occurs. An illustration of this process is

shown in Figure 4. It is important to note that two-dimensional cross-correlation is the same

operation as convolution, except that the resulting values of the convolution are normalised into

correlation coefficients. These coefficients are described by the following equation:

𝛾( 𝑢, 𝑣) =

∑ [𝑓( 𝑥, 𝑦) − 𝑓′

𝑢,𝑣

][ℎ( 𝑥 − 𝑢, 𝑦 − 𝑣) − ℎ′]𝑥,𝑦

√∑ [𝑓( 𝑥, 𝑦) − 𝑓′

𝑢,𝑣

]

2

𝑥,𝑦 ∑ [ℎ( 𝑥 − 𝑢, 𝑦 − 𝑣) − ℎ′]2

𝑥,𝑦

Where,

ℎ′

𝑖𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛 𝑜𝑓 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑓𝑖𝑙𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑔𝑒

𝑓′ 𝑢,𝑣 𝑖𝑠 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑛 𝑜𝑓𝑓( 𝑥, 𝑦) 𝑖𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑟𝑒𝑔𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝑢𝑛𝑑𝑒𝑟 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑓𝑖𝑙𝑡𝑒𝑟.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-14-2048.jpg)

![Page | 8

Figure 4: Visualisation of two dimensional convolution.

Source: http://fourier.eng.hmc.edu/e161/lectures/digital_convolution_2D.gif

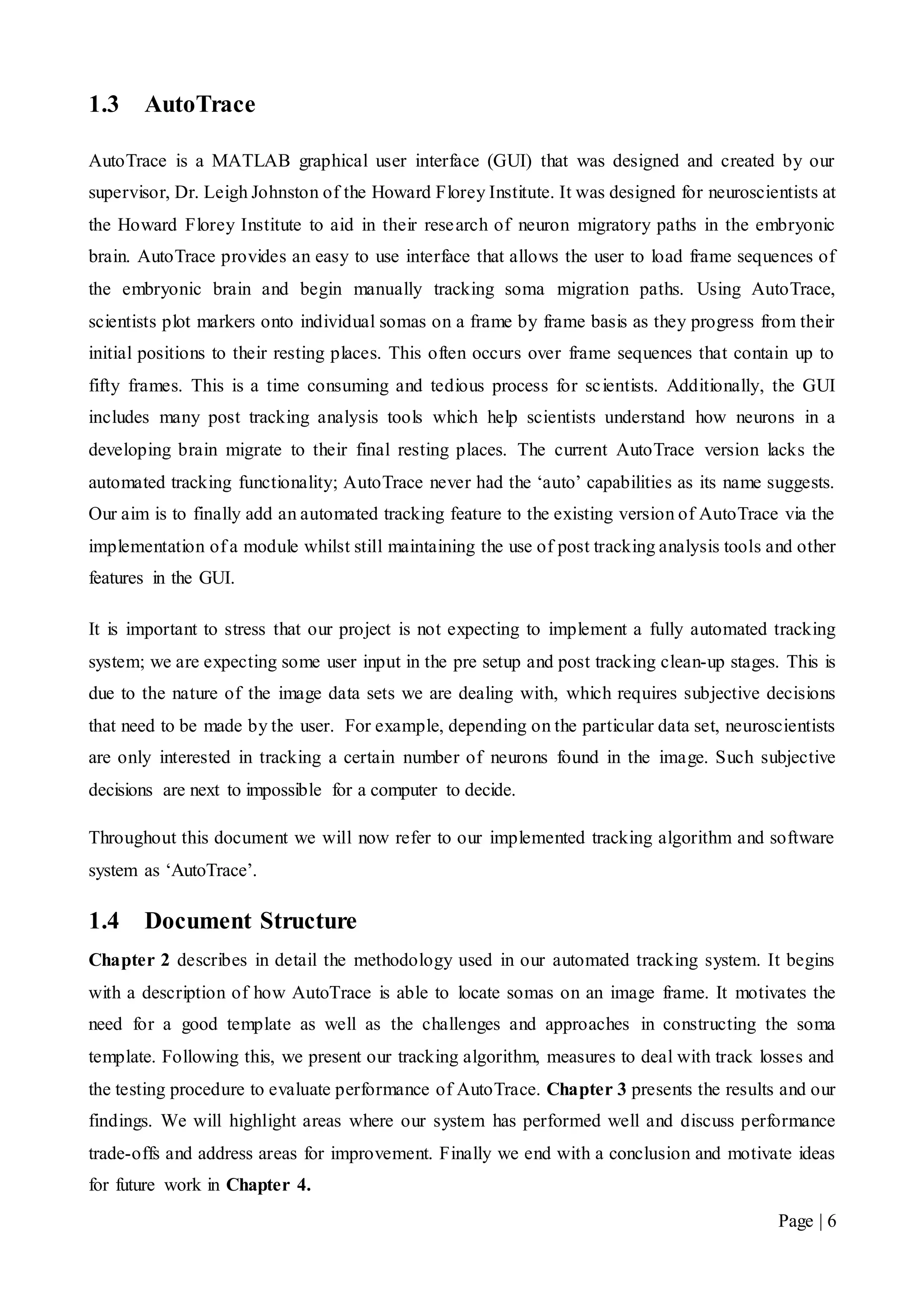

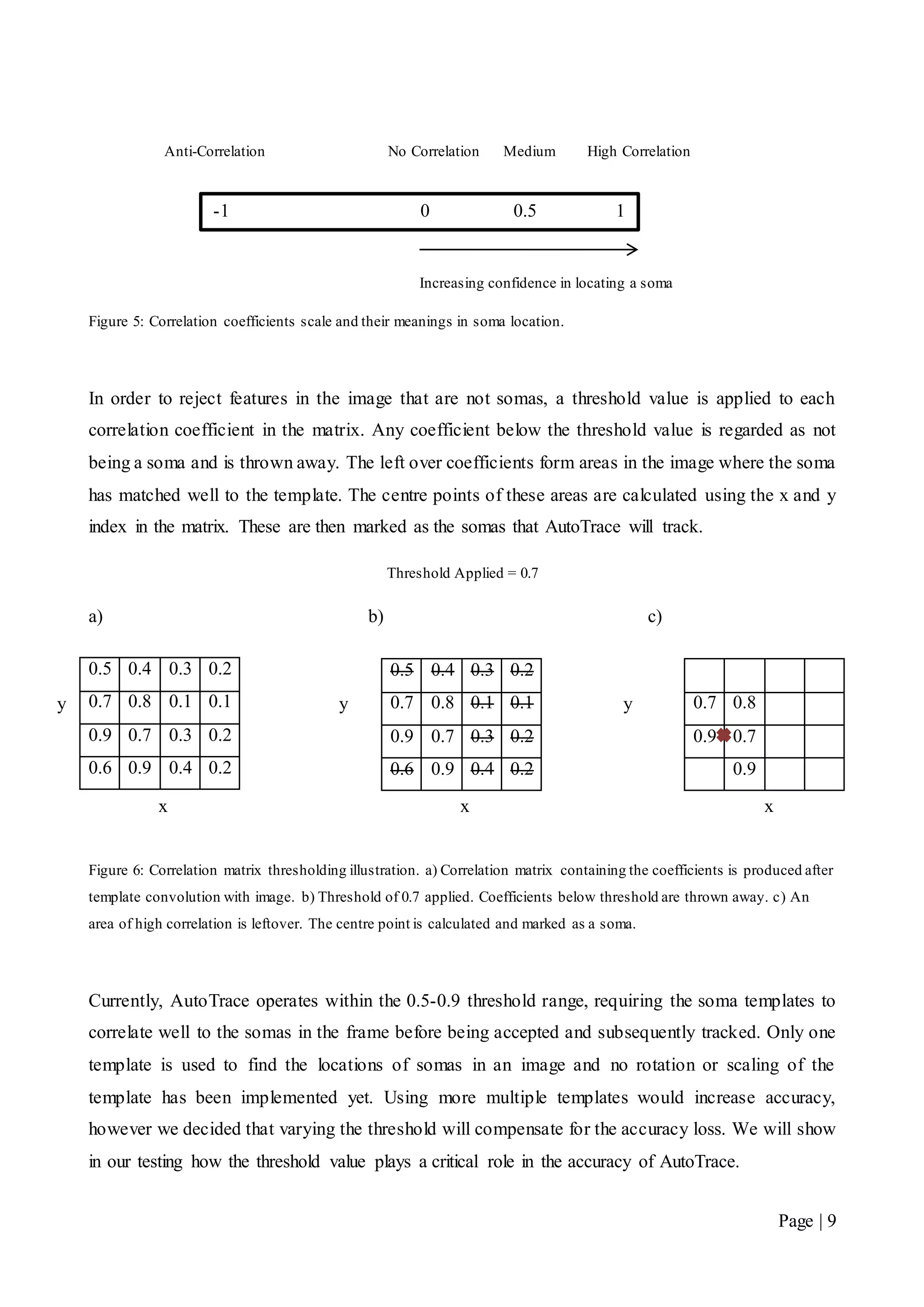

2.2 Locating Somas

In order to track somas, there needs to be a means for a computer to find them inside an image.

AutoTrace uses a process called template matching, which performs a two-dimensional correlation

of a soma template image over a frame and analyses the correlation coefficients [10].

Both the template image and the frame are represented as a two-dimensional matrix of grey scale

intensity values. The result of performing the template correlation with the frame is a correlation

matrix filled with coefficients. A coefficient value of 0 translates to no correlation with the template,

and no confidence in finding a soma at that location. Conversely, a coefficient of 1 translates to

high correlation and confidently suggests that a soma has been located at that position in the image.

The correlation scale shown in Figure 5, illustrates the correlation coefficients and their meanings.

Template matrix =

Image

matrix =

Convolution

matrix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-15-2048.jpg)

![Page | 32

Bibliography

[1] F. Gilbert, Developmental Biology, 6th ed., Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates,

Sunderland, 2000.

[2] J. Britto, L. Johnston, and S. Tan, “The Stochastic Search Dynamics of Interneuron

Migration”, Biophysical Journal, vol. 97, pp. 699–709, Aug. 2009.

[3] C. Metin, J. Baudoin, S. Rakic, and J. Pamavelas, “Cell and molecular mechanisms

involved in the migration of cortical interneurons”, European Journal of Neuroscience,

vol. 23, pp. 894–900, 2006.

[4] J. Gleeson, “Neuronal migration disorders”, Mental Retardation and Developmental

Disabilities Research Reviews, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 167–171, Aug. 2001.

[5] A. Sacan, H. Ferhatosmanoglu, and H. Coskun, “CellTrack: An Open-Source Software

for Cell Tracking and Motility Analysis”, Bioinformatics, vol. 00, no. 00, pp. 1-3, 2008.

[6] E. Cheng, S. Challa, R. Chakravorty, J. Markham, “Microscopic Cell Segmentation by

Parallel Detection and Fusion Algorithm”, Proc. of Multimedia Signal Processing 2008,

pp. 94-100

[7] D. Wang, R. Lagerstrom, C. Sun, L. Bischof, P. Vallotton, and M. Götte, “HCA-Vision:

Automated Neurite Outgrowth Analysis”, Journal of Biomolecular Screening, vol. 15,

no. 9, pp. 1165-1170, Oct. 2010.

[8] M. Kass, A. Witkin, and D. Terzopoulos, “Snakes: Active contour models”,

International Journal of Computer Vision, pp. 321–331, 1987.

[9] R. E. W. Rafael, C. Gonzalez, Digital Image Processing, Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.

[10] J. P. Lewis, “Fast Template Matching”, Vision Interface, pp. 2-3, 1995.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/84ff69e8-2944-4557-b412-291eb1b3af35-150825234919-lva1-app6891/75/Final-Year-Project-Report-Candidate-3-39-2048.jpg)