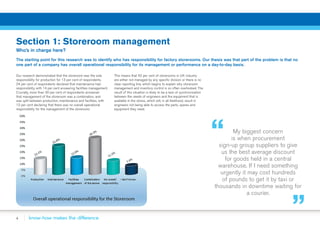

The document discusses issues with factory storerooms in UK manufacturing. It finds that 42% of storerooms have no clear division responsible for management or reporting lines. Over half of facilities keep over £250,000 of inventory on site, but 27% keep less than £50,000, showing an imbalance. Only 16% conduct monthly stocktakes, with many doing so annually or quarterly. Over 30% of facilities use no formal management system like software, relying on basic spreadsheets. Most facilities make limited use of MRO suppliers, mainly for fast supply of items not in stock. The document aims to understand why factory floors are often lean but storerooms are chaotic and inefficient.