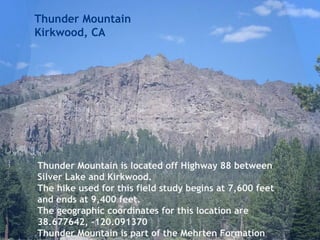

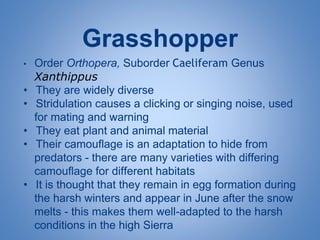

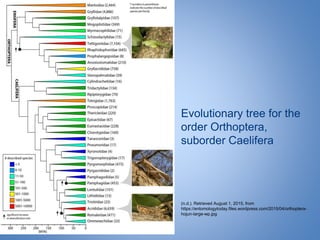

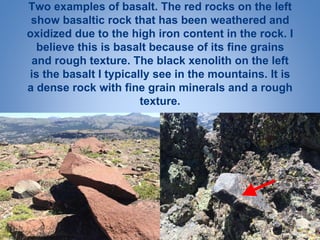

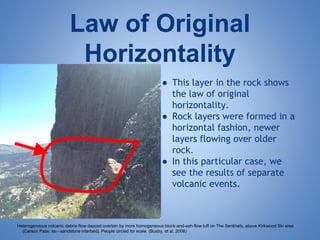

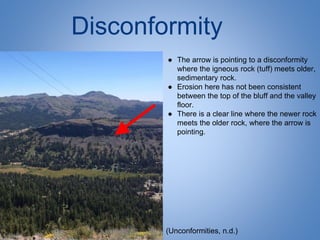

The document discusses the geological features of Thunder Mountain, located in Kirkwood, California, detailing its formation from volcanic and tectonic activity over millions of years. It highlights the types of rocks found in the area, such as breccia and basalt, as well as local flora like the ponderosa pine and grasshopper species. The field study incorporates evidence of geological processes, including uplift, erosion, and glaciation, alongside references to related scientific literature.