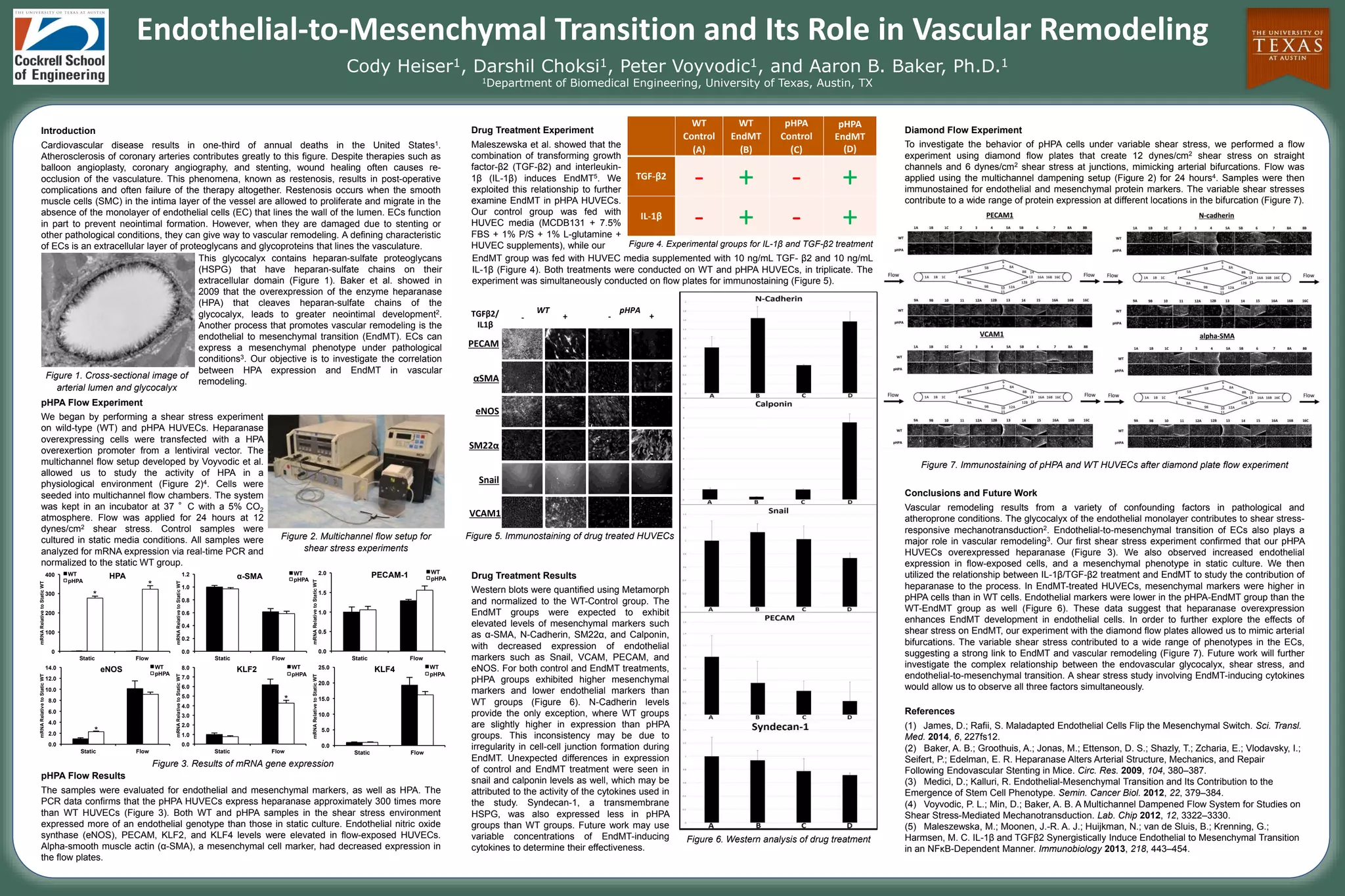

This document summarizes research investigating the correlation between heparanase (HPA) expression and endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) in vascular remodeling. The researchers found that overexpression of HPA in endothelial cells enhanced EndMT development. In shear stress experiments, HPA overexpression increased expression of mesenchymal markers and decreased expression of endothelial markers. Treatment with cytokines that induce EndMT also increased mesenchymal markers and decreased endothelial markers in HPA overexpressing cells compared to wild type cells. Experiments using variable shear stress mimicking arterial bifurcations demonstrated a link between shear stress and EndMT in vascular remodeling. Future work will further study the relationship between the endothelial glycocalyx, shear stress, and