Etiopathology and management of Malignant melanoma.pptx

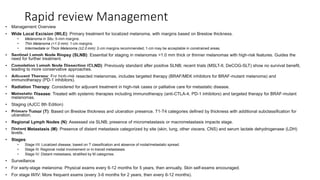

- 1. Rapid review Management • Management Overview • Wide Local Excision (WLE): Primary treatment for localized melanoma, with margins based on Breslow thickness. • Melanoma in Situ: 5-mm margins. • Thin Melanoma (<1.0 mm): 1-cm margins. • Intermediate or Thick Melanoma (≥2.0 mm): 2-cm margins recommended; 1-cm may be acceptable in constrained areas. • Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLNB): Essential for staging in melanomas >1.0 mm thick or thinner melanomas with high-risk features. Guides the need for further treatment. • Completion Lymph Node Dissection (CLND): Previously standard after positive SLNB; recent trials (MSLT-II, DeCOG-SLT) show no survival benefit, leading to more conservative approaches. • Adjuvant Therapy: For high-risk resected melanomas, includes targeted therapy (BRAF/MEK inhibitors for BRAF-mutant melanoma) and immunotherapy (PD-1 inhibitors). • Radiation Therapy: Considered for adjuvant treatment in high-risk cases or palliative care for metastatic disease. • Metastatic Disease: Treated with systemic therapies including immunotherapy (anti-CTLA-4, PD-1 inhibitors) and targeted therapy for BRAF-mutant melanomas. • Staging (AJCC 8th Edition) • Primary Tumor (T): Based on Breslow thickness and ulceration presence. T1-T4 categories defined by thickness with additional subclassification for ulceration. • Regional Lymph Nodes (N): Assessed via SLNB; presence of micrometastasis or macrometastasis impacts stage. • Distant Metastasis (M): Presence of distant metastasis categorized by site (skin, lung, other viscera, CNS) and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. • Stages: • Stage I/II: Localized disease, based on T classification and absence of nodal/metastatic spread. • Stage III: Regional nodal involvement or in-transit metastases. • Stage IV: Distant metastasis, stratified by M categories. • Surveillance • For early-stage melanoma: Physical exams every 6-12 months for 5 years, then annually. Skin self-exams encouraged. • For stage III/IV: More frequent exams (every 3-6 months for 2 years, then every 6-12 months).

- 3. Introduction • Historical background: • Hippocrates mentioned descriptions likely related to melanoma. • John Hunter published the first modern account of surgical melanoma treatment in 1787. • René Laennec coined the term "cancer noire" and named the disease melanosis as visceral deposits. • Ongoing research has improved our understanding of melanoma over the years. • Epidemiology: • Melanoma accounts for less than 2% of skin cancer cases. • It is the fifth most common cancer in men and sixth in women in the United States. • Melanoma causes the majority of skin cancer-related deaths. • In 2018, there were 91,270 new melanoma cases and 9,320 deaths in the U.S. • Melanoma incidence has steadily increased worldwide, attributed to sun exposure and better detection. • Highest incidence in Australia, New Zealand, North America, and northern Europe.

- 4. • Risk factors: • Lighter skin tones have a higher risk. • Fair complexion, blonde/red hair, blue eyes, sunburn-prone individuals are at increased risk. • Incidence is higher in non-Hispanic white individuals. • Melanoma slightly more common in men across most races/ethnicities. • Occurs predominantly in middle-aged adults, but can affect all ages. • About one in six new cases occurs in patients younger than 45 years old. • Genetic risk factors: Fitzpatrick types I and II skin, family history, xeroderma pigmentosum. • Other risk factors: prior history of melanoma, large number of nevi, dysplastic nevi, environmental factors like intense UV radiation exposure. • Intense, intermittent, UV-A (has deeper skin penetration)

- 5. Precursor lesions • Melanoma within preexisting lesions: • Up to 40% of melanomas can develop within preexisting lesions. • These lesions include dysplastic nevi, congenital nevi, and Spitz nevi. • Familial and hereditary factors: • 5-10% of melanoma patients have a family history of the disease. • Syndromes like dysplastic nevus syndrome, familial atypical multiple mole-melanoma syndrome, and B-K mole syndrome are associated with melanoma. • These syndromes involve melanoma in family members and a high number of melanocytic nevi, often classified as atypical or dysplastic. (>100 moles) • Patients with these syndromes require regular dermatologic evaluation and periodic biopsies of suspicious lesions. • Pancreatic cancer may also be present in the family history. • Dysplastic nevi: • Dysplastic nevi are flat pigmented skin lesions, typically 6-15 mm in size, with indistinct margins and variable color. • Distinguishing between dysplastic and non-dysplastic nevi can be challenging, requiring long-term monitoring. • While most nevi are benign, some may progress to invasive melanoma with additional mutations. • Biopsy is recommended for suspicious dysplastic nevi. • Dysplastic nevi can have mild, moderate, or severe dysplasia on histologic examination. • Mild dysplasia may not require excision, but close observation is needed.

- 6. • Congenital nevi: • Risk of melanoma is proportional to the size and number of congenital nevi. • Small to medium-sized congenital nevi pose a low risk and do not require observation unless they change. • Giant congenital nevi (over 20 cm) are rare but carry an increased lifetime melanoma risk, requiring consideration of complete excision. • These patients are also at risk for other tumors, particularly sarcomas. • Spitzoid melanocytic lesions: • Spitzoid lesions range from benign Spitz nevi to spitzoid melanoma. • Spitz nevi are typically benign, rapidly growing, pink or brown skin lesions with minimal melanoma progression risk. • In adults, spitzoid lesions may have atypical features or represent melanoma with spitzoid features. • Atypical features include size over 10 mm, asymmetry, ulceration, and poor circumscription. • Diagnosis can be challenging, and consultation with a dermatopathologist is recommended. • Complete excision with negative margins is appropriate for unequivocal Spitz nevi. • For lesions with potential melanoma concern, wide local excision with appropriate margins is performed. • Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is used for invasive spitzoid melanomas and as a prognostic measure in indeterminate cases. • The routine use of SLN biopsy for atypical Spitz tumors is controversial due to the presence of atypical cells without clear prognostic significance.

- 9. Pathogenesis • Melanoma has the highest mutational burden among studied malignancies. • Collaborative efforts like The Cancer Genome Atlas Network have significantly advanced our understanding of melanoma's molecular mechanisms. • Genomic Subtypes: [@ BiRaTNagar ma Melanoma] • Four distinct subtypes identified: BRAF, RAS, NF1, and triple-wild-type. • BRAF subtype (50% cases) most common, with V600E and V600K mutations. • RAS subtype (30% cases) and NF1 subtype (15% cases) follow in frequency. • Triple-wild-type subtype lacks major mutations, with low UV signature changes (30%). • MAPK Signaling Pathway: • Canonical pathway for melanogenic effect is the MAPK signaling pathway. • Gain-of-function mutations in BRAF and RAS or loss of inhibitory steps (NF1) lead to unchecked cellular growth.

- 10. First major pathway Second major pathway

- 11. • Tumor Suppressor Genes and Neoplastic Development: • Additional loss of tumor suppressor genes is necessary for melanoma development. • CDKN2A mutations (25-40% familial melanomas) result in loss of INK4A and ARF proteins. • INK4A prevents cell cycle progression, ARF regulates p53 levels to initiate apoptosis. • Loss of INK4A or ARF removes cell cycle checkpoints, increasing replication risk. • PI3/AKT Pathway: • Second major pathway in melanoma pathogenesis. • Altered in all genomic subtypes. • PI3 stimulates AKT, promoting cellular proliferation via mammalian target of rapamycin. • PTEN inhibits PI3/AKT signaling; loss of PTEN (25-50% nonfamilial melanomas) leads to therapy resistance against BRAF/MEK inhibition.

- 12. Initial evaluation of melanoma • Melanoma Presentation: • Melanoma typically appears as an irregular pigmented skin lesion that has either grown or changed in appearance over time. • Diagnosis and the decision to perform a biopsy are often guided by the ABCDE criteria (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, Diameter >6 mm, Evolution/change). • Patient Assessment: • When evaluating a patient suspected of having melanoma, a comprehensive history and physical examination are essential. • The history should focus on primary melanoma details, such as how long the lesion has been present, any changes observed over time, and any associated symptoms like itching or bleeding. • Risk factors like sun exposure, tanning bed use, family history, immunosuppression, prior cancer history, and other relevant factors should be explored. • During the physical examination, a complete assessment of the skin, including visual inspection and touch (palpation), is conducted to identify suspicious skin lesions. • Palpation of the lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, and groin is also performed, depending on the location of the primary lesion.

- 13. • Challenges in Detection: • Benign skin lesions can mimic malignant melanoma • Seborrheic keratoses, • Amelanotic melanomas, • Any changes in the size, color, shape, itching, or bleeding of a skin lesion warrant a low threshold for biopsy. Ignoring such changes by saying "let's keep an eye on it" is generally discouraged. • Metastasis and Advanced Disease: • Rare 5% METASTATIC , 10% REGIONAL SPREAD. • 3 types are seen (Regional, in-transit and Distant) • Regional disease involves the spread of tumor to the lymph nodes that receive drainage from the primary tumor site. • In-transit melanoma/ satellite lesion is a type of regional lymphatic metastasis where tumor spreads within the lymphatic channels, resulting in visible cutaneous or subcutaneous nodules between the primary tumor site and regional lymph nodes. • Distant metastasis refers to the spread of melanoma to distant organs through the bloodstream. • Although rare at initial diagnosis, it is important to inquire about symptoms of metastatic disease, such as masses, neurologic symptoms, anorexia, weight loss, bone pain, or respiratory symptoms.

- 14. Biopsy • Skin Biopsy Types: • Primary care physicians, dermatologists, and surgeons should be trained to perform skin biopsies. • Three main types of skin biopsy: excisional, incisional (including punch biopsy), and shave biopsy. a. Excisional Biopsy: • Suitable for small lesions, completely removes the pigmented skin lesion. • Local anesthesia is administered, and a narrow margin excision is performed, with sutures used to close the resulting defect. • Depth of excision should reach the subcutaneous fat for a full-thickness biopsy. • Consideration is given to the orientation of the excision, facilitating subsequent wider excision if necessary. b. Incisional Biopsy (Punch Biopsy): • Useful for larger lesions, offers a tissue diagnosis before complete excision. • Involves the use of a punch biopsy instrument to remove a 2-8 mm cylindrical section of skin and subcutaneous tissue. • Generally followed by closure with one or two simple sutures. • Punch biopsies of at least 4 mm are recommended for adequate tissue evaluation. • Biopsy is taken from the thickest or most suspicious-looking part of the lesion, and multiple punches may be taken for larger lesions.

- 16. c. Shave Biopsy: • Commonly used by dermatologists but traditionally discouraged for melanoma diagnosis due to potential inaccuracies in assessing Breslow thickness. • Performed by elevating the skin lesion and shaving it with a razor blade or scalpel. • Hemostasis is achieved using topical agents or electrocautery. • The wound heals by secondary intention without sutures, making it a popular method. • Potential drawback: Shave biopsy may transect the lesion, affecting accurate thickness assessment. • To address this, deep shave or saucerization biopsies may be performed, removing the lesion down to subcutaneous fat when necessary. • Pathologic Evaluation: • All pigmented lesions should undergo pathologic evaluation using fixation and permanent section. • Practices such as cryotherapy, cautery, or lasers for the ablation of pigmented skin lesions should be discouraged, as they can lead to delays in diagnosis.

- 17. Pathology • Pathology in Melanoma: • The biopsy report is crucial for evaluating new skin lesions and developing a treatment plan. • Pathologists may classify equivocal lesions as melanoma due to the severe consequences of a missed diagnosis. • Pathology reports may describe lesions as ranging from severely dysplastic nevi to melanoma in situ or early invasive melanoma. • Prudent action is to treat such lesions as early invasive melanoma with a 1-cm margin wide local excision (WLE). • Histology and Growth Patterns: • Invasive cutaneous melanoma is categorized into four major types based on growth patterns and locations: lentigo maligna melanoma, superficial spreading melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma, and nodular melanoma. • Melanomas initially grow in the basal layer of the skin, expand radially in the epidermis and superficial dermal layer (radial growth phase), and later grow vertically into the deeper layers (vertical growth phase), potentially leading to metastasis.

- 19. • Common Histologic Types (Types of cutaneous melanoma): [@ LANDS] • Superficial Spreading Melanoma: Most common, found on the trunk and proximal extremities. Starts as a flat-pigmented lesion with irregular borders and various pigments. May later develop a vertical growth phase. • Lentigo Maligna Melanoma: Occurs on sun-exposed areas in older individuals, appears as a flat, variably pigmented lesion with irregular borders. Progresses slowly and may become large before diagnosis. • Acral Lentiginous Melanoma: Arises in subungual areas under nails and on the palms and soles. Most common in nonwhite patients and often diagnosed at an advanced stage. • Nodular Melanoma: Raised papular lesions that can appear anywhere on the body. May not always follow ABCDE criteria and often have a poor prognosis due to greater thickness and frequent ulceration. • Desmoplastic Melanoma: Characterized by melanoma cells and prominent stromal fibrosis. Can be challenging to diagnose, often amelanotic. Classified as pure or mixed, with varying risk profiles for metastases.

- 21. • Depth Assessment: • Depth assessment is a critical factor in melanoma prognosis. • Breslow thickness, measured from the top of the granular layer to the lowest tumor cell, is commonly used and categorized as • thin (<1 mm), • intermediate thickness (1-4 mm), • thick (>4 mm). • Breslow thickness has largely replaced Clark level for predicting prognosis, as it is a more accurate method. • Thicker melanomas are associated with worse prognoses.

- 22. TNM-AJCC staging • Staging of Melanoma: • The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) uses a tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification for cutaneous melanoma. • Important prognostic factors considered in this staging system include • Breslow thickness • Ulceration • Nodal status • Lymphatic spread manifestations. • T Stage (Primary Tumor): • T classification is based on Breslow thickness measured to the nearest one- tenth of a millimeter. • Tumors are further subclassified as T1–4 based on ulceration, with cut-points at 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 mm. • Ulceration is defined by the absence of an intact epithelium and is a crucial prognostic factor. • The eighth edition of the AJCC staging system made important changes, including the reclassification of T1b melanomas, which are defined by ulceration at any thickness or thickness of 0.8 to 1.0 mm without ulceration. • Mitotic rate, previously used to designate T1b melanomas, is no longer used.

- 23. • N Stage (Regional Lymph Node Involvement): • Tumor burden is categorized as • Clinically occult disease detected by SLN biopsy • Clinically apparent nodal disease includes palpable, enlarged lymph nodes or those identified on imaging as abnormal and confirmed by needle biopsy. • The eighth edition of AJCC staging guidelines stratify non nodal regional disease, including in-transit cutaneous or subcutaneous metastases, microsatellite, or satellite metastases, by N category according to the number of regional lymph nodes (N1c, N2c, or N3c). • M Stage (Distant Metastasis): • The eighth edition of the AJCC staging guidelines stratifies M categories by anatomic site of distant disease and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels. • Subgroups are defined by distant skin, soft tissue, nonregional lymph nodes (M1a), lung (M1b), noncentral nervous system viscera (M1c), and central nervous system (M1d). • Elevated serum LDH levels further subclassify M1a-d groups, indicating worse prognosis across all types of metastatic disease.

- 24. Staging (TNM)

- 26. 2/3 involved- micromets with 1 tumor-involved nodes 1 involved – micromets with 0 tumor-involved nodes ≥4 involved-2 micromets- any matted nodes

- 28. Additional Factors: • Several factors that impact survival are not integrated into the AJCC staging system, such as patient age, melanoma location, and gender. • Surgeons should also be aware of features in pathology reports, including tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), which can suggest a host immune response and are associated with a more favorable prognosis. • Other factors like regression, histologic subtype, and mitotic rate (still reported in pathology) should be considered in clinical evaluation, but their impact on survival varies.

- 29. Additional workup and imaging • Patients with localized stage I or II melanoma No further workup • In stage III melanoma, the use of additional imaging after sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is debated. • Stage IV melanoma requires imaging to assess the extent and resectability of metastatic lesions. • For advanced cases, PET/CT, CT scans (chest, abdomen, pelvis), and brain MRI are generally recommended.

- 30. Treatment • Wide Local Excision : • Randomized controlled trials have established current guidelines based on primary tumor thickness. • Margin Recommendations: • Melanoma in Situ: Typically recommended 5-mm margins. Challenges include difficulty achieving negative margins and diagnostic uncertainty. • Thin Melanoma (<1.0 mm): Generally, 1-cm margins are sufficient. • Intermediate or Thick Melanoma (≥2.0 mm): Recommended margins are 2 cm, though 1-cm margins are acceptable in some areas, understanding that it may lead to higher local recurrence. • Technique of Wide Local Excision (WLE): • Usually performed under local anesthesia; general anesthesia preferred for patients undergoing SLN biopsy or lymphadenectomy. • Margins are measured from the lesion edge or previous biopsy scar using a fusiform incision. • Excision includes skin and subcutaneous tissue, with fascia excision rarely necessary. • Permanent section pathology is used; frozen section analysis of margins is not routine.

- 31. • Special Cases and Considerations during WLE: • Subungual melanomas may require digit amputation. • Ray amputations for finger melanomas are usually unnecessary. • Resection should achieve histologically negative margins, based on grossly measured margins. • Mohs Micrographic Surgery (MMS): • Involves sequential tangential excision of skin cancers with immediate margin assessment. • Commonly used for non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) like SCCs and BCCs. • For melanoma, MMS is preferred for cosmetically sensitive areas, but its use remains controversial. • Success can vary with operator experience, and full pathologic examination of excised margins is required. • MMS is generally not considered Oncologically acceptable for melanoma, except in the hands of experienced centers in highly selective cases.

- 32. Lymph node management in malignant melanoma

- 33. • Evaluation and Management of Regional Lymph Nodes in Melanoma: • Sentinel Lymph Node (SLN) biopsy is now the foundation for assessing intermediate and thick cutaneous melanoma. • Indications for completion lymph node dissection (CLND) following a positive SLN biopsy have evolved. • Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SLN): • Introduced in 1992 by Dr. Donald Morton, SLN biopsy is vital in staging cutaneous melanoma. • Required for staging melanoma over 1.0 mm in thickness (per AJCC). • SLN status is the most significant prognostic factor for melanoma patients without clinical nodal metastases. • Indications for SLN Biopsy: • NCCN guidelines recommend considering SLN biopsy for T2 or greater (>1.0 mm) melanomas and thinner lesions with a 5% or higher risk of a positive SLN. • Controversy exists regarding SLN biopsy for thin (T1) melanomas and thick (T4, >4.0 mm) melanomas. • Assessing Thin Melanomas: • Some T1 melanomas have features linked to increased nodal spread risk, like ulceration and high mitotic rate. • Recent changes to AJCC staging for T1 melanomas have made assessment more complex. • Use of mitotic rate, age, and thickness can identify thin melanomas at increased risk for SLN metastases. • SLN Biopsy for Thick Melanomas: • Previously, thick melanomas were thought not to benefit much from SLN status information. • However, studies show that thick melanoma patients with tumor-negative SLN have a better

- 34. • Technical Aspects of SLN Biopsy: • Lymphoscintigraphy is performed preoperatively, typically on the same day as SLN biopsy. • Technetium-99 sulfur colloid is injected into the dermis to identify sentinel nodes. • Injecting the radioactive tracer too deeply can lead to failure in detecting sentinel nodes. • Handheld gamma probes identify sentinel nodes, with definitions for removal based on radioactivity, blue dye presence, or palpable abnormalities. • Head and Neck Challenges: • SLN biopsy in the head and neck is more challenging due to rich lymphatic drainage. • Cross-sectional imaging aids in identifying precise anatomic locations of SLNs. • Knowledge of anatomy in this region is crucial to prevent neurologic injury. • Cervical SLNs can be found adjacent to the spinal accessory nerve, which should be preserved. • Parotid SLNs may require superficial parotidectomy to avoid facial nerve injury.

- 35. The MSLT-I trial demonstrated that SLN biopsy provides better disease-free outcomes, and the status of the sentinel node is a strong predictor of recurrence or death from melanoma, particularly in patients with intermediate thickness lesions.

- 37. • Lymph Node Dissection in Melanoma: • Historically, lymph node dissection was an important part of melanoma treatment. • However, the advent of SLN biopsy and a better understanding of melanoma biology have reduced its importance. • Elective lymph node dissection is mainly of historical interest, as SLN biopsy accomplishes the same goals with lower morbidity. • Despite this, lymph node dissection remains relevant, and surgeons should be familiar with its technical details and indications. • Completion Lymphadenectomy (CLND): • CLND involves removing the remaining lymph nodes in a regional nodal basin with metastatic melanoma identified by SLN biopsy. • Patients with SLN-positive melanoma exhibit a wide range of prognosis. • CLND helps identify nonsentinel node metastases, which is a crucial prognostic factor. • Micrometastatic disease in nonsentinel nodes is more aggressive with a worse prognosis. • CLND may have potential therapeutic benefits by removing additional nodes with micrometastatic disease, improving disease-free survival. • However, CLND significantly increases short- and long-term morbidity, including wound complications, paresthesias, and lymphedema. • Only a small percentage of SLN-positive patients have additional micrometastatic nonsentinel nodes, so many patients undergo CLND without therapeutic benefit.

- 38. • Predicting Non-sentinel Node Metastases: • Efforts to predict non-sentinel node metastases have focused on clinical and pathologic factors. • Various scoring systems evaluate the burden of micro metastatic disease, and maximum tumor deposit diameter is the most prognostically significant measure. • Ongoing research aims to combine clinical and pathologic factors with genetic markers for better risk assessment of non-sentinel node metastases. • In the future, this predictive ability may guide patient selection for adjuvant therapy rather than CLND. • Studies on CLND vs. Observation: • Two studies, DeCOG-SLT and MSLT-II, investigated the survival benefits of CLND after a tumor-positive SLN biopsy. • Both studies showed no significant difference in melanoma-specific survival between CLND and observation. • The majority of SLN-positive patients do not have additional micro metastatic disease, making routine CLND unnecessary. • The studies established that it is safe and reasonable to avoid CLND for most SLN-positive patients.

- 39. • Therapeutic Lymph Node Dissection: • Therapeutic lymph node dissection is used for regional nodal basin lymphadenectomy when clinically apparent nodal metastases are present. • It achieves locoregional disease control and will likely be the most common reason for lymphadenectomy in the future. • Fine needle aspiration is used to confirm suspected nodal metastases in patients with palpable lymph nodes or radiographic abnormalities. • Benign lymphadenopathy may be found but should be concerning for metastatic disease until proven otherwise. • Palliative resection of bulky, painful regional lymphadenopathy can be considered. • Careful removal of all fibrofatty and lymphatic tissue in the involved regional nodal basin is performed in therapeutic lymph node dissection. • Procedures differ depending on the anatomical location (e.g., axillary, inguinal, cervical lymphadenectomy) and may involve divisions of muscles or vessels as needed. • Deep pelvic nodal dissection may be necessary for patients with macroscopic disease confined to the superficial inguinal nodal basin or when imaging suggests involvement of pelvic nodes. Cloquet node and involvement of multiple femoral nodes are traditional indications for pelvic dissection. • For cervical lymphadenectomy, a functional neck dissection is often sufficient while sparing vital structures like the internal jugular vein and spinal accessory nerve. Superficial parotidectomy may be performed based on lymphoscintigraphy and SLN results. • Epitrochlear or popliteal lymphadenectomy is frequently unnecessary but requires careful attention to anatomical details.

- 41. • Adjuvant Therapy in Melanoma: • Recent advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy have transformed the landscape of adjuvant therapy for melanoma, offering new hope for patients after surgical treatment. • Historically, the prognosis for advanced melanoma was grim due to the lack of effective systemic therapies, and melanoma surgery has seen minimal changes in recent decades. • Historical Adjuvant Therapy: • High-dose interferon alfa-2b was the only adjuvant systemic therapy approved by the FDA before 2015. • Interferon therapy was associated with severe toxicity and offered only marginal effectiveness. • Clinical trials demonstrated short-term disease-free and overall survival benefits for high-risk patients with palpable nodal disease but only modest improvements in disease-free survival. • Targeted Therapy: • Vemurafenib was the first successful targeted therapy, specifically designed for melanoma with the BRAF V600E mutation. • The success of BRAF inhibition led to the development of dual BRAF-MEK inhibition, a strategy that overcame some of the resistance issues seen with single-agent BRAF inhibition. • The COMBI-AD trial showed remarkable results with dual BRAF-MEK inhibition in patients with completely resected stage III BRAF-mutant melanoma, improving relapse-free survival and overall survival. • However, questions remain about the long-term durability of this strategy, especially given that patients often develop resistance to targeted therapy. • Additionally, these trial populations included patients who underwent completion lymphadenectomy for SLN-positive disease, while the current trend is to omit completion lymphadenectomy in most SLN-positive patients.

- 42. • Immunotherapy: • Adjuvant immunotherapy emerged similarly to targeted therapy, with early experience in metastatic disease leading to adjuvant therapy trials. • Ipilimumab, a monoclonal anti-CTLA-4 antibody, was the first immunotherapy agent approved for adjuvant therapy. • The EORTC 18071 study demonstrated that adjuvant ipilimumab improved recurrence-free survival and overall survival in resected stage III melanoma. • However, the use of ipilimumab was associated with increased risks of serious adverse events and death. • PD-1 inhibitors, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, offered safer and equally effective immunotherapy options. The Checkmate 238 trial and the EORTC 1325/KEYNOTE-054 trial showed improved recurrence-free survival with these agents in resected stage III melanoma. • Preference between nivolumab and pembrolizumab is usually institution- specific, with no data suggesting one is more effective than the other. • The optimal adjuvant treatment strategy for patients with BRAF-mutant melanoma who are also candidates for adjuvant immunotherapy remains a topic of discussion.

- 44. • Radiation Therapy: • Historically, melanoma was believed to be relatively resistant to radiation therapy. • Recent studies have suggested roles for radiation therapy in the adjuvant and palliative settings, possibly as an adjunct to systemic immunotherapy. • Adjuvant radiation therapy may be considered for select patients at high risk of lymph node basin recurrence after lymphadenectomy. • Radiation therapy has been shown to reduce the cumulative incidence of lymph node field relapse in high-risk patients, but its overall impact on survival is not entirely clear. • High-risk patients with regional nodal disease may benefit more from improved adjuvant systemic therapy (immunotherapy) to reduce the risk of metastatic recurrence.

- 45. Surveillance of a melanoma

- 46. • Surveillance for resected melanoma is tailored to detect recurrences or new primary melanomas. • Surveillance should be individualized based on the patient's risk and the likely site of recurrence. • For early stage (0-II) melanoma: • Every 6 months for the first 3 years: history and physical examination. • At least annual exams thereafter. • Patients should be educated about recognizing symptoms of recurrence. • For stage III and high-risk stage II melanoma: • Every 3-4 months for the first 3 years: history and physical examination. • Every 6 months for the next 2 years. • Annual exams thereafter. • Consider laboratory and imaging tests based on individual risk. • Stage IV melanoma patients require regular clinical, laboratory, and radiologic evaluations to monitor treatment response. • Melanoma survivors are at increased risk of second primary melanomas: • Lifelong regular skin exams are recommended. • A survivorship team, including the surgeon, dermatologist, and medical oncologist, should oversee surveillance and risk assessment.

- 48. Treatment of Locoregional disease • Based on the nature of recurrence • Local recurrence Excision • In-transit disease SLNB followed by excision • Regional nodal disease • Therapeutic nodal dissection followed by adjuvant therapy [less preferred] • Neoadjuvant therapy (BRAF-MEK inhibition) then resection and adjuvant therapy (Preferred) • Unresectable disease Immunotherapy/ T-VEC therapy

- 50. Metastatic disease • Anti- CTLA4 antibody Ipilimumab • PD-1 inhibitor Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab • Targeted therapy • Vemurafenib • Dabrafenib • Combination therapy (BRAF-MEK) inhibition • Resistance occurs due to upregulation of alternative signaling pathways including MAPK pathway. • Trametinib + Dabrafenib therapy • Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) • Metastasectomy

- 53. • Unknown Primary Melanoma: • Occurs in less than 2% of all melanoma cases and less than 5% of cases with metastatic disease. • Requires a thorough skin examination, including rare sites (perianal area, external genitalia, nail beds, scalp, and external auditory canal). • Endoscopic evaluations (oral cavity, nasopharynx, anus, rectum) may identify mucosal melanoma. • Consider history of prior pigmented skin lesions and clinical evidence of vitiligo. • Some unknown primary melanomas may arise from benign nevus cells within lymph nodes.

- 54. • Melanoma and Pregnancy: • One-third of women diagnosed with melanoma are of childbearing age. • No established link between pregnancy and melanoma risk. • Hormonal changes during pregnancy don't explain melanoma development. • Pregnant women with suspicious pigmented lesions require appropriate workup. • Melanoma prognosis during pregnancy is similar to nonpregnant patients. • Early termination of pregnancy doesn't offer therapeutic benefit. • Wide local excision (WLE) can be safely performed under local anesthesia. • Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy may be considered, avoiding vital blue dye. • Placental examination for melanoma presence may be advisable.

- 55. • Noncutaneous Melanoma: • Ocular Melanoma: • Arises within the eye's retina and uveal tract. • Most common intraocular malignancy in adults in the United States. • Metastases primarily occur in the liver. • Less responsive to immunotherapy compared to cutaneous melanoma. • Mucosal Melanoma: • Common sites: head and neck, oral cavity, oropharynx, nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, anal canal, rectum, female genitalia. • Often diagnosed at advanced stages with poor prognosis. • Extensive local resections may be necessary for local disease control. • Radiation therapy can improve locoregional disease control. • Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy role not well established but considered for some mucosal melanomas. • Immunotherapy response rate for mucosal melanoma is similar to cutaneous melanoma; considered for adjuvant and metastatic treatment.