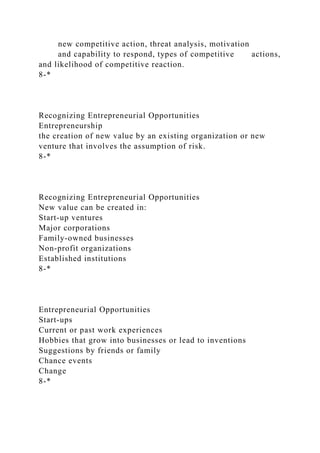

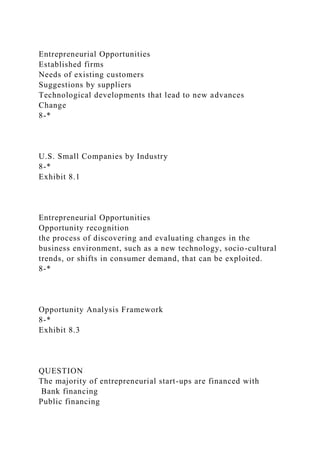

This chapter discusses the role of new ventures and small businesses in the U.S. economy, exploring how opportunities, resources, and entrepreneurs impact entrepreneurial success. It outlines various entry strategies and competitive dynamics, highlighting the importance of opportunity recognition and evaluation as well as the characteristics of viable opportunities. Additionally, the text emphasizes entrepreneurial leadership and strategic decision-making in the face of competition and market demands.