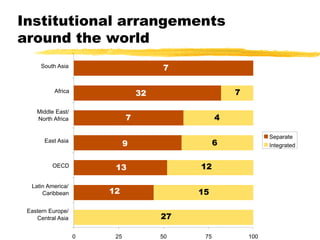

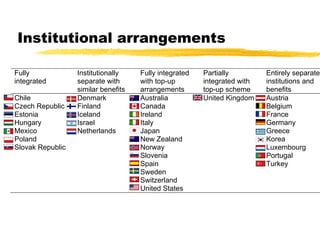

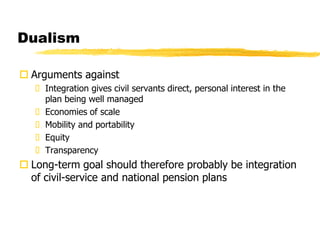

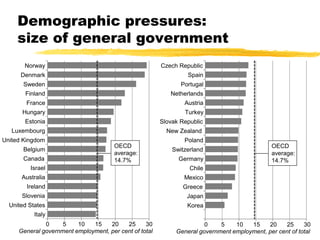

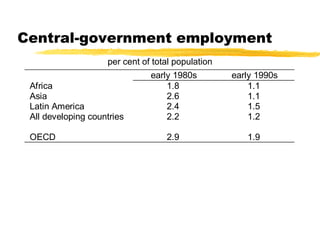

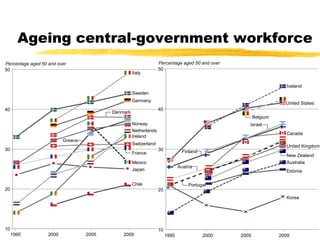

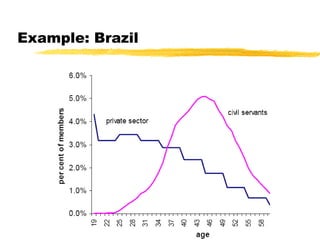

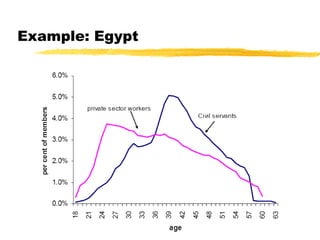

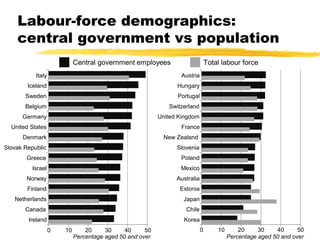

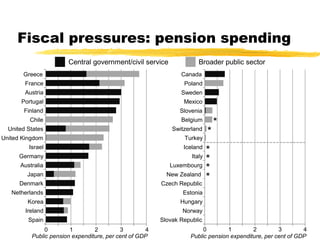

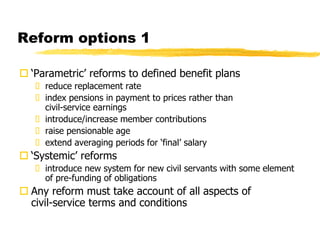

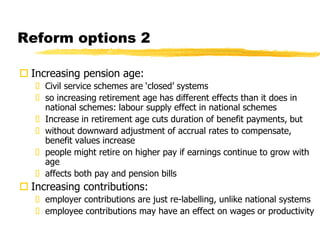

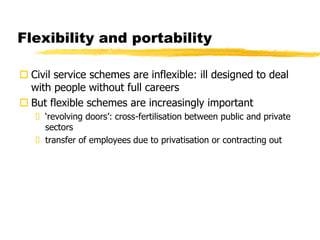

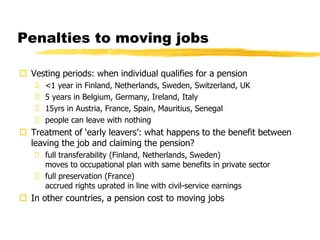

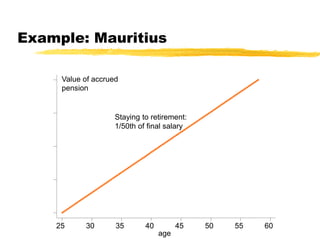

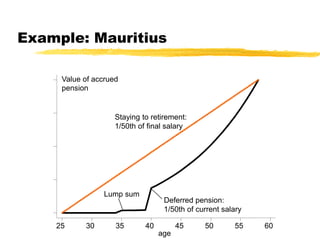

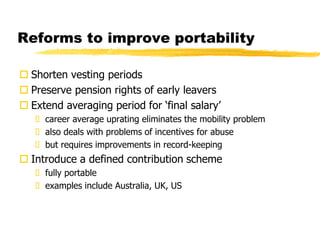

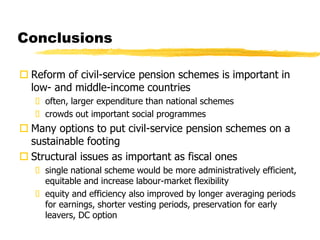

This document discusses options for reforming civil service pension schemes. It covers the origins and institutional arrangements of such schemes around the world. Key issues addressed include demographic pressures from an aging workforce, fiscal pressures from rising pension costs, and lack of flexibility and portability that hinders mobility. Reform options proposed are parametric changes like reducing benefits or raising retirement ages, as well as systemic changes like introducing pre-funding or defined contribution plans. Reforms aim to integrate separate civil service schemes, improve sustainability, and enhance flexibility.