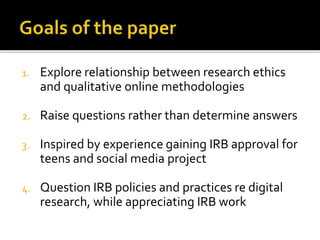

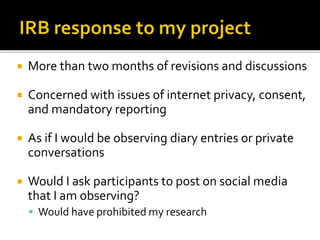

This document discusses issues related to conducting qualitative online research involving human subjects and gaining IRB approval. It raises questions about how IRB policies address digital research methods and the relationship between regulatory definitions of research and ethnographic practices. Specifically, it explores tensions between viewing online content as either public data exempt from IRB versus social interactions that require consideration of privacy and potential harm. The document also questions whether U.S. IRB standards are more restrictive than other countries due to litigiousness and discusses challenges around classifying adolescent participants.