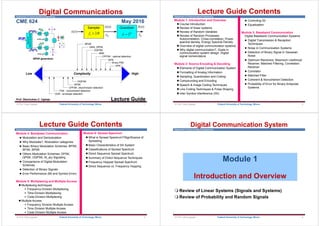

1. The document provides a lecture guide for a digital communications course covering topics like source encoding and decoding, baseband communication, bandpass communication, multiplexing, and spread spectrum.

2. The course is divided into 6 modules covering topics such as an introduction to signals and systems, random variables, probability, linear systems, Fourier transforms, and digital modulation schemes.

3. The guide outlines the contents of each module including reviews of prerequisite material and overviews of key concepts in digital communication systems.

![Department of Communications Engineering

Signals - 2

Mathematically, a signal is defined as a function of one

or more independent variables, e.g.,

x(t) = 10t

x(t) = 5t2

s(x,y) = 3x + 2xy + 10y2

Sometimes the functional dependence on the

independent variable is not precisely known, e.g.,

speech signal

Sometimes a signal is a combination of other signals

e.g., sum of sinusoid of different amplitudes,

frequency & phase

1

( ) ( )sin 2 ( ) ( )

n

i i i

i

s t A t F t t

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 9

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Signals - 3

Mathematically, a signal is defined as a function of one or

more independent variables, e.g.,

x(t) = 10t

x(t) = 5t2

s(x,y) = 3x + 2xy + 10y2

Sometimes the functional dependence on the independent

variable is not precisely known, e.g., speech signal

Sometimes a signal is a combination of other signals

e.g., sum of sinusoid of different amplitudes, frequency & phase

Signals are the inputs outputs, and internal functions that

the systems process or produce, such as voltage,

current, pressure, displacements, intensity, etc.

1

( ) ( )sin 2 ( ) ( )

n

i i i

i

s t A t F t t

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 10

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Signals - 4

The variable time may be continuous or discrete and the

value of the signal may be represented as

Continuous-valued x(t)

Discrete-valued x(nts)

Quantized xQ(t), and

Digital x[n]

These types of signals occur at different stages of the

process

Other variables (distance, angle, etc.) can also be the

independent variable, especially for 2-D signals like

images and video

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 11

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Physical realizable signals must

Have time duration

Occupy finite frequency spectrum

Are continuous (as in analog signal)

Have finite peak value, and

Are real-valued

All real-world signals will have these properties

Sometimes we use mathematical signal models which violate

these conditions

e.g., Dirac delta function (or impulse function)

The most commonly used analog signals are the sinusoidal

signals (sine, cosine, etc.)

In communication systems, we are concerned with info

bearing signals that evolve as a function of the independent

variable, t

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 12

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Signals - 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-3-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

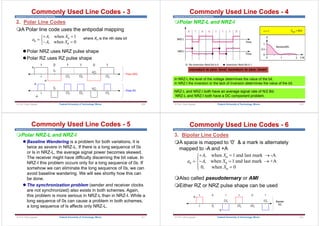

Broad Classification of Systems

We are

interested only

on the systems

that intersect the

dotted path.

Distributed

Parameters

SYSTEMS

Lumped Parameters

Stochastic Deterministic

Continuous Time Discrete Time

Nonlinear Linear

Nonlinear Linear

Time

Varying

Time

Invariant

Time

Varying

Time

Invariant

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 17

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Systems - 5 Department of Communications Engineering

Operation on Linear Systems

An operator, T, is a rule to transform one function to another

Additive

Homogeneous

Principle of Superposition

Superposition implies both additive & homogeneous rules

If a system fails either rule, the function is nonlinear

Addition or homogeneity is sufficient condition to test for

linearity

T x t y t

( ) ( )

T x t x t T x t T x t

1 2 1 2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

k p k p k p

T Kx t KT x t

( ) ( )

T Ax t Bx t AT x t BT x t

1 2 1 2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

k p k p k p

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 18

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Systems - 6

Department of Communications Engineering

Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) Systems

Linear systems are characterized by the ability to accept

input and produce output in response to the input

Most communication systems can be modeled as linear

systems with signals forming the input and output functions

h(t)

h[n]

H(ejw)

H(f)

H(z)

LTI

y(t)

y[n]

Y(ejw)

Y(f)

Y(z)

x(t)

x[n]

x(ejw)

X(f)

X(z)

Time Function

Pole-Zero Plot

Difference Equation

H - Function

Frequency Function

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 19

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Why study signals and systems?

In signals and systems theory we study the definition

and description of signals, and the behavior of systems

under different conditions

Signals form the inputs, outputs and internal

functions of systems

In electrical & computer engineering, the understanding

of signals and the behavior of systems is of immense

importance

Communication engineers are concerned with systems

which transmit, receive, and process signals carrying

information

Hence before one can characterize a system, one must

be able to characterize the system

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 20

Federal University of Technology, Minna](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-5-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Some Important or Common Signals & Functions

Sinusoidal Signal

Complex Exponential (harmonics)

Unit Step Function [denoted by u(t)]

Ramp Function [denoted by r(t)]

Rectangular Pulse Function [denoted by rect(t) or

(t)]

Triangular Pulse Function[denoted by (t)]

Sign (Signum) Function [denoted by sgn(t)]

Sinc Function [denoted by sinc(t)]

Impulse (Delta, Dirac) Function [denoted by (t)]

Signals and Spectra - 6

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 29

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Operations on Signals

Amplitude Scaling

Amplitude Shifting

Time Shifting

Displaces a signal in time without changing its

shape

Signals and Spectra - 7

( ) ( )

"+"shifts the signal left by

"-" shifts the signal right by (delayed)

y t x t

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 30

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Time Scaling

Slows down or speeds up time which results in signal

compression or stretching

The expression

Reflection or Folding

A scaling operation with = -1 x(t) = x(-t)

The mirror image of x(t) about the y-axis through t = 0

Operations in Combinations

x(t) delay (shift right) by x(t-)

compress by x(t-)

x(t) compress by x(t)

delay (shift right) by / x(t-)

Signals and Spectra - 8

( )

t

y t x

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 31

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Some useful signal operations and models

Continuous/Discrete Convolution

Parseval’s’ theorem

Hilbert Transform

Concept of Bandwidth and Filtering

Some Important Properties of Signals

DC Value

Is the time average of a signal or the time average

over a finite interval [t1, t2]

Average Power

The ensemble average

RMS Value

Signals and Spectra - 9

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 32

Federal University of Technology, Minna](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-8-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

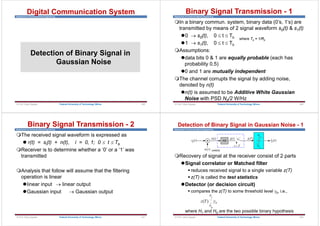

Digital Representation of Analog Signals

Most practical signal of interest are analog in nature

e.g., speech

biological signals

seismic signals

radar signals

sonar, and

various communication signals (audio, video, text, etc)

Conversion to digital form is necessary

Interface

(A/D)

Analog

Signal

Digital

Signal

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 73

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Sampling

Digital Communication System

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 74

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Digitization of Analog Signals

1. Sampling: obtain samples of x(t) at uniformly spaced

time intervals

2. Quantization: map each sample into an approximation

value of finite precision

Pulse Code Modulation: telephone speech

CD audio

3. Compression: to lower bit rate further, apply additional

compression method

Differential coding: cellular telephone speech

Subband coding: MP3 audio

Compression discussed in Chapter 12

© Prof. Okey Ugweje Federal University of Technology, Minna 75

Department of Communications Engineering

Transmitter Side Encoding

(Formatting Analog Information)

Structure of Digital Communication Transmitter

Analog-to-Digital (A/D) Conversion

Sampling Quantization

Digital

Modulation

Input

Signal

Transmitted

Signal

Transmitter

Sampler Quantizer

xa(t)

Analog signal

A/D Converter

Discrete-time

signal

Quantized

signal

x[n] xq

(n)

Quantized

Output Signal

Analog Input

Signal

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 76

Federal University of Technology, Minna](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-19-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Quantization - 1

Sample values require infinite # of bits for perfect

representation since sampler output still continuous in

amplitude

each sample can take on any value, e.g. 4.752, 0.001, etc

the number of possible values is infinite

To transmit as a digital signal we must restrict the # of

possible values to finite bits

Sampler Quantizer

x(t)

Analog signal

A/D Converter

Discrete-time signal Quantized signal

x[n] xq

(n)

Analog

Input

signal

Quantized

output signal

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 89

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Quantization - 2

Definition:

Quantization is the process of approximating

continuous-valued samples with a finite number of

bits

Quantizer

device that operates on a discrete-time signal to

produce finite # of amplitudes by approximating the

sampled values

maps each sampled value to one of pre-assigned

output levels

the process of “rounding off” a sample according to

some rule

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 90

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

e.g., suppose we must round to the nearest tenth,

then:

4.752 4.8

0.001 0

rounds off the sample values to the nearest

discrete value in a set of L quantum levels

quantized samples xq(n) are discrete in time (by

virtues of sampling) and discrete in amplitude (by

virtue of quantization)

Because we are approximating the analog sample

values by using finite # of levels, L, error is

introduced during quantization

Quantization - 3

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 91

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Definition

number, size, location of its quantizing cell

boundaries, and step size of the quantization process

Quantization Resolution

# of bits, n, used to represent each sample

where L = number of levels

more bits results in better fidelity

However, the bit rate is higher and more bandwidth is required

Xq

(nT)

X[nT] Quantizer

random process

Quantizer Model and Definitions - 1

n L

log2

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 92

Federal University of Technology, Minna](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-23-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Mathematical Description of Quantizer - 3

Signal-to-quantization noise ratio (SQNR) (or

simply SNR)

From above equation, average SNR can be written as

2

2

2

2 2

2

2

{ }

( )

( )

{ } { }

ˆ

( ) ( )

ˆ

avg

X

X

Signal Power

S

NoisePower

N

E x

E e t

x f x dx

E x E x

D x x f x dx

E x x

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 113

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

We have assumed

1. e(t) is uniformly distributed

2. {e(t)} is a stationary white noise process, i.e. e(j)

and e(k) are uncorrelated for j = k

3. e(t) is uncorrelated with the input signal x(t), and

4. signal sample xs(t) is zero mean and stationary

As a rule of thumb, each bit of quantization increases

the SNR by 6 dB provided that

a) xs(t) has a uniform distribution, and

b) the quantizer is a uniform quantizer

Mathematical Description of Quantizer - 4

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 114

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

If the input signal is a sequence, then

1

2

0

1

[ ]

N

S s

n

P x n

N

1

2

0

1

[ ]

N

N

n

P e n

N

1

2

0

1

2

0

[ ]

[ ]

N

s

S n

N

N

n

x n

P

SNR

P e n

Signal power

Noise power

Signal-to-noise ratio

Mathematical Description of Quantizer - 5

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 115

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Given

q = step size, max quantization error is

where L = 2n is the # of quantization levels

The noise variance of the quantization error is given by

L/2 –1 positive levels

L/2 –1 negative levels

1 zero level

1

pp pp

V V

q

L L

SNR for Uniform Quantizer - 1

2 2 2 2

1 1

2 2 2

2 2 2

2

3 2

2

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

1

3 12

q q q

q q q

q q

q

q

error p e de e de e de

q

e

q

Equation 13.12

L –1 level

L –2 intervals

This is the MSE

(noise variance)

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 116

Federal University of Technology, Minna](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-29-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Non-uniform Quantization - 5

Error is the weighted sum of error powers in each

quantile

weighted by p(xn)qn

If the quantizer has uniform quantiles (i.e., UQ), then

If the Q does not operate in the saturation region, then

2

2

1

2 2

0

1

2

0

2

2

2 ( )

12

1

2

12 2

1

2 1

12 12

2 2

L

L

Lin n n n

n

n n

n n

q p x q

q q

q L

q

L

q q

q L

2 2

q Lin

125

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

##Uniform vs. Nonuniform Quantization

Let

Numerical integration will indicate that

However, NQ will yield a better result

The “best” possible quantizer has

NQ can give better performance for most signals than UQ

f x e

X

x

( )

1

2

2

2

. , . , . , .

x x x x

1 1494 2 0498 3 0498 4 1494

l q

D E x

01188 1

2

. , [ ]

S

N

dB

avg

F

H

I

K F

H

I

K

10

1

01188

9 25

10

log

.

.

S

N avg

dB

FH IK 12 0

.

126

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Types of Noise in Quantizer

Overload Noise (Saturation Noise)

when input signal > Lmax resulting in clipping of signal

Granularity Noise (Quantization Noise)

when L are not finely spaced apart enough to accurately

approximate input signal

Truncation or Rounding error

This type of noise is signal dependent

Timing Jitter

Error caused by a shift in the sampler position

Easily isolated with stable clock reference and power

supply isolation

127

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Reading Assignment:

Differential Quantization

Is used to reduce the dynamic range

Interpolation from previous value if samples are

correlated

Correlation can be increased by oversampling

Important/Practical Systems Using Quantization - 1

x

Differeence

Value

(k+2)T

(k+3)T

kT

Actual data

predited (linear interpolation)

Oversampling Predictor Differential

more samples/sec fewer samples/sec

128

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-32-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Differential PCM (DPCM)

Delta Modulation

Linear Predictive Coding

Adaptive Predictive Coding

Important/Practical Systems Using Quantization - 2

129

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

20.Example 20

Quantization

21.Example 21

Uniform Qantrizer

Department of Communications Engineering

Example 22: (uniform quantization)

Sampler

f B

s 2

Quantizer

2n

L

x n

( )

xk

xk

( )

x n

x t

( )

n = # of binary bits used to

represent each sample

fs = sampling frequency or

sampling rate

= quantized

value of x(t)

2q

1

2 q

q k

x

ˆk

x

3q

2q

q

3q

3

2 q

5

2 q

7

2 q

1

2 q

3

2 q

5

2 q

7

2 q

111

110

101

100

011

010

001

000

ˆ ˆ[ ] [ ]

k q

x x n x n

Uniform Quantizer

130

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Let the quantization level be {1,3,5,7}. Assume that

the input signal to a quantizer have the pdf shown

a) Compute the signal mean power

b) Compute the mean square error at the quantizer

output

c) Compute the output SNR

d) How would you change the distribution of the

quantization level in order to decrease the

distortion?

Example - Quantization

f x

x

else

x

( )

,

,

R

S

T

32 0 8

0

1

4

x t

( )

8

f x

( )

131

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Federal University of Technology, Minna 132

Companding

Digital Communication System

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-33-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Types of Companding - 2

In U.S., telephone lines uses = 255

Samples 4 kHz speech waveform at 8,000

sample/sec

Encodes each sample with 8 bits, L = 256 quantizer

levels

Hence data rate R = 64 kbit/sec

= 0 corresponds to uniform quantization

141

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

A-Law Companding (Europe, China, Russia, Asia,

Africa)

where

x and y represent the input and output voltages

A is a constant number determined by experiment, A = 87.6

You can find the companding gain by differentiating

the output

y x

y

A x

x

A

x

x

x A

y

A x

x

A

x

A

x

x

e

e

( )

sgn( ),

log

log

sgn( ),

max

max

max

max

max

max

FH IK

L

NM O

QP

R

S

|

|

|

T

|

|

|

1

0 1

1

1

1 1

G

d

dx

y x

x

( )

0

See eqn. 2.23

Types of Companding - 3

142

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Federal University of Technology, Minna 143

Encoding

Digital Communication System

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Quantizer output is one of L possible signal levels

For binary transmission, each quantized sample is

mapped into an n-bit binary word

Encoding is the process of representing each of

the L outputs of the quantizer by an n-bit code

word

one-to-one mapping - no distortion introduced

xa(t)

Analog

signal

A/D Converter

Discrete-Time

signal

Quantized

signal

x[n] xq[n]

Sampler Quantizer

Line

Coder

an

Encoding - 1

144

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-36-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) - 3

153

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) - 4

154

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Advantages of PCM

Relatively inexpensive

Easily multiplexed

PCM waveforms from different sources can be

transmitted over a common digital channel (TDM)

Easily regenerated:

useful for long-distance communication e.g., telephone

Better noise performance than analog system

Modem is all digital, thus affording reliability, stability and is

readily adaptable to integrated circuits

Signals may be stored and time-scaled efficiently (e.g.,

satellite communication)

Efficient codes are readily available

Disadvantage

Requires wider bandwidth than analog signals

Pulse Code Modulation (PCM) - 5

155

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Implementation of A/D Converters

Serial Input Output (SIO) circuit converts quantization

level to a sequence of bits n = log2 L

ADC SIO

( )

x f x

x n bits

Quantizer

Sampler Quantizer Coder

xa(t)

Analog signal

A/D Converter

Discrete-Time signal Quantized signal Digital signal

x[n] xq[n]

n

156

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-39-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Generation of Line Codes

Transmitter:

The FIR filter realizes the different pulse shapes

Baseband modulation with arbitrary pulse shapes can be detected by

correlation detector

matched filter detector (this is the most common detector)

ROM

Make

Impulse

h[n] = p[n]

0 -1

1 +1

binary

bits

an anp[n]

an [n]

s[n]

impulse train which

represents the data

pulse shape defined by impulse

response of FIR filter

N

5N

3N

2N

4N

0

1 1 1 1

0 0

N 5N

3N

2N 4N

0

1 1 1 1

0 0

241

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Federal University of Technology, Minna 242

Pulse Shaping

Inter-symbol Interference

Digital Communication System

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Baseband Communication System

Baseband Communication System:

We have been considering the transmitter side

Transmitted signal is created by the line coder

according to

where an is the information sequence & g(t) is pulse shape

s t a g t nT

n b

n

( ) ( )

A/D

Converter

Line

Coder

Channel

Analog Input To Receiver

an s t

( )

Transmiter

A/D

Converter

Line

Coder

Channel

Input

an s t

( )

Transmiter

Decoder

A/D

Converter

Receiver

Output

243

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Problems with Line Codes - 1

A) Line codes are not bandlimited

absolute bandwidth, B, is infinite

power outside the 1st null bandwidth is not negligible

i.e., power in the sidelobes can be quite high

This can cause Adjacent Channel Interference (ACI)

If transmission channel is bandlimited, then high freq

components will be cut off

High freq components correspond to sharp transition in

pulses

Hence, the pulse will spread out

If pulse spreads out into adjacent symbol period, then

inter-symbol interference (ISI) occurred

244

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-61-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

At the output of the demodulator

where ai(t) is the signal component & noise n is zero mean

Gaussian

At the sampling instant t = T

For simplicity we will drop the index such that z = ai + n

0 0

1 1

( ) ( ) ( ), 0 for a binary 0

( )

( ) ( ) ( ), 0 for a binary 1

z t a t n t t T

z t

z t a t n t t T

0 0

1 1

( ) ( ) ( ), 0 for a binary 0

( )

( ) ( ) ( ), 0 for a binary 1

z T a T n T t T

z T

z T a T n T t T

Maximum Likelihood Detector (MLD) - 4

353

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

z(T) is known as decision variable or test statistics

and it is a random process corrupted by noise

Assume that pdf of z0(T) and z1(T) are Gaussian with

equal likelihood, and with 0 = a0, 1 = a1

a0

Region 0

Likelihood of s0

Region 1

Likelihood of s1

Decision

Line

P[z|s1 sent]

P[z|s0 sent]

Pe(s0)

a0

o

p z s z a

( | ) exp

0

0

0

0

2

1

2

1

2

F

HG I

KJ

L

NM O

QP

p z s z a

( | ) exp

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

2

F

HG I

KJ

L

NM O

QP

Minimum error criterion

0

0 1

2

0

a a

Maximum Likelihood Detector (MLD) - 5

354

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

This is an averaging operation

It makes sense because the logical point is halfway

between the two voltage levels representing each

symbol

Questions:

How do we implement this averaging operation?

How do we choose the threshold, 0?

Hypothesis:

H0: r(t) = s0(t) + n(t) “0” sent

H1: r(t) = s1(t) + n(t) “1” sent

Maximum Likelihood Detector (MLD) - 6

355

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Definitions of Probabilities:

P[s0], P[s1] a priori probabilities

These probabilities are known before transmission

P[z]

probability of the received sample

p(z|s0), p(z|s1)

conditional pdf of received signal z, conditioned on the class si

P[s0|z], P[s1|z] a posteriori probabilities

After examining the sample, we make a refinement of our previous

knowledge

P[s1|s0], P[s0|s1]

wrong decision (error)

P[s1|s1], P[s0|s0] correct decision

Maximum Likelihood Detector (MLD) - 7

356

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-89-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Decision Rule:

Acquiring information at the receiver about the transmitted

signal involves making decisions

We must decide which of the set of hypothesis best

describes the received signal

This involves uncertain (error in judgment)

If the signals we are trying to detect do not overlap, we

can make a decision without error

On the contrary, we need some rules to help classify the

received signal once they fall in the overlap region

A set of rules known as decision rules allow us to decide

( )

ˆi

z t

0

z T

( )

1

H

0

H

Maximum Likelihood Detector (MLD) - 8

357

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

1. Bayes’ decision criterion:

It formulates the problem of making a decision

under conditions of uncertainty by selecting the

hypothesis with the greatest a posteriori probability

This scheme assumes that some errors are more

costly than others

Hence, it assigns cost (weighting factors) that

reflect the risk involved

This is the most widely applied decision rule in

communications

Types of Decision Rules - 1

358

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

2. Maximum a posteriori (MAP) criterion:

Decide that the received signal belongs to the class

with the maximum a posteriori probabilities, i.e.,

maximize P(si|z)

It equivalently examines the pdf conditioned on

each signal class (p(z|s0), p(z|s1)) and choose the

maximum

For the received signal za, the likelihood that za

belongs to s1 or s2 corresponds to the circled point

on the pdf

The decision criterion is based on the likelihood of

P[z|si], i = 0,

Types of Decision Rules - 2

359

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

3. Newman-Pearson (N-P) criterion

Makes no assumption on the a priori source

statistics (requires only a posteriori probabilities)

Widely used in pulse detection in Gaussian noise as

in Radar applications where the source probabilities

(presence or absence of a target) is unknown

fix probability of false alarm

minimize probability of error

maximize probability of correct decision

Types of Decision Rules - 3

360

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-90-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

4. Min-max criterion

Also in this criterion, the a priori probability is not

known

Since P(H1) is unknown, the rule maximizes the risk

with respect to P(H1) and minimizes the risk with

respect to P(H0)

Types of Decision Rules - 4

361

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 1

Recall that the Bayes equation is given by

where

Recall from probability theory that

In communications, we can interpret the Bayes’

equation as a description of an experiment involving

a received sample, and

a statistical knowledge of the signal classes to

which the received sample may belong

1

[ ] [ | ] [ ]

M

i i

i

P z P z s P s

[ | ] [ ]

[ | ] , 0,2, , 1

[ ]

i i

i

P z s P s

P s z i M

P z

[ | ] [ ] ( | ) [ ]

i i i

P s z P z p z s P s

362

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

That is,

si denote the ith transmitted signal class from a set

of M classes

zj denotes the jth sample of the received signal

Hence, we can write the Bayes equation in terms of

the pdf

where

( | ) [ ]

[ | ] , 0,2, , 1

( )

i i

i

p z s P s

P s z i M

p z

1

( ) ( | ) [ ]

M

i i

i

p z p z s P s

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 2

363

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

By examining a particular received sample zj, it is

possible to find likelihood that zj belongs to class si

This means that after the experiment, we will refine our

knowledge by computing the a posteriori probability

Note that the terms a priori and a posteriori imply

“cause to effect” and “effect to cause,” respectively

Assume that

Pdf of z0(T) and z1(T) are Gaussian with equal

likelihood, having mean values of a0 and a1 respectively

a0 and a1 are mutually independent

Noise n0 is independent zero mean AWGN with PSD No

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 3

364

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-91-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

In this case, for binary signal

The last equation corresponds to making a decision

based on the comparison of received signal to some

threshold level

1 0

[ | ] [ | ] decision rule

P s z P s z

0 0

1 1 ( | ) [ ]

( | ) [ ]

( ) ( )

p z s P s

p z s P s

p z p z

1 1 0 0

( | ) [ ] ( | ) [ ]

p z s P s p z s P s

0

1

0 1

[ ]

( | )

( ) likelihood ratio test (LRT)

( | ) [ ]

P s

p z s

L z

p z s P s

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 4

365

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

The right-hand side (RHS) is called the likelihood ratio

When the two signals, s0(t) and s1(t), are equally likely,

i.e., P[s0] = P[s1] = 0.5, then the decision rule becomes

In terms of the Bayes criterion, it implies that the cost of

both types of error is the same

This type of decision rule is called the maximum a

posteriori (MAP) criterion (or minimum error

criterion)

0

1

0 1

[ ]

( | )

( ) likelihood ratio test (LRT)

( | ) [ ]

P s

p z s

L z

p z s P s

1

0

( | )

( ) 1 max likelihood ratio test

( | )

p z s

L z

p z s

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 5

366

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Substituting the pdfs

2

0

0 0

0 0

1 1

: ( | ) exp

2 2

z a

H p z s

2

1

1 1

1 1

1 1

: ( | ) exp

2 2

z a

H p z s

2

1

2

1

1 1

2

0

0

2

0

0

1

1

( )

exp

2

( | ) 2

( ) 1 1

1

1

( | )

( )

exp

2

2

z a

p z s

L z

p z s

z a

2 2

0 1

2 2

1 0 1 0

2 2

0 0

( ) ( )

exp 1

2

z a a a a

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 6

367

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Taking the log of both sides will give

Hence

where z is minimum error criterion and 0 is optimum threshold

2 2

1 0 1 0

2 2

0 0

( ) ( )

ln{ ( )} 0

2

z a a a a

L z

2 2

1 0 1 0 1 0 1 0

2 2 2

0 0 0

( ) ( )( )

2 2

z a a a a a a a a

2

0 1 0 1 0

2

0 1 0

( )( )

2 ( )

a a a a

z

a a

1 0

0

( )

2

a a

z

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 7

368

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-92-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

For antipodal signal, s1(t) = - s0(t) a1 = - a0

This means that if received signal was positive, s1(t)

was sent, else s0(t) is sent

0

z

Bayes’ Decision Criterion - 8

369

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Probability of Error - 1

Error will occur if

s1 is sent s0 is received

P[H0|s1] = P[e|s1]

s0 is sent s1 is received

P[H1|s0] = P[e|s0]

The total probability of error is the sum of the errors

0

1 1

[ | ] ( | )

P e s p z s dz

0 0

0

[ | ] ( | )

P e s p z s dz

2

1 1 0 0

1

0 1 1 1 0 0

( , ) [ | ] [ ] [ | ] [ ]

[ | ] [ ] [ | ] [ ]

B i

i

P P e s P e s P s P e s P s

P H s P s P H s P s

o

ao a1

0 1

o

ao a1

0 1

See pp. 121~122 & section

B.2

370

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

If signals are equally probable

Hence, PB, is probability that an incorrect hypothesis is

made

Think of PB as the area under the tail of either of the

conditional distributions, p(z|s1) or p(z|s2), i.e.,

0 1 1 1 0 0

1

0 1 1 0

2

[ | ] [ ] [ | ] [ ]

[ | ] [ | ]

B

P P H s P s P H s P s

P H s P H s

1

1 0

0 1 1 0

2

[ | ]

[ | ] [ | ]

B

by symmetry

P P H s

P H s P H s

1 0 0

0 0

2

0

0

0 0

( | ) ( | )

1 1

exp

2 2

B

P p H s dz p z s dz

z a

dz

Probability of Error - 2

371

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

This equation cannot be evaluated in closed form

This is the famous Q-function or complementary error

function

Hence,

1 0

0

2

B

a a

P Q

1 0

2

0

0

0 0

0

0

0

2

( )/ 2

1

1 1

exp

2 2

( )

,

1

exp *

2 2

B

a a

z a

P dz

z a

u du dz

u du A

Probability of Error - 3

372

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-93-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Pe is minimized by choosing h(t) or H(f) such that optimum

threshold 0 is minimized

That is

A note on the Q(x) - complementary (co) error function

Equivalent Definitions

For large arguments (x large), Q function

2

2

0 1 0 1

0 0

( ) ( ) [ ( ) ( )]

2 4

a t a t a T a T

or

2

1

( ) exp

2 2

x

Q x

x

1

( ) e

2 2

x

Q x rfc

e 2 2

rfc Q

x x

Probability of Error - 4

373

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Federal University of Technology, Minna 374

Correlator

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Correlator-Type Receiver - 1

The correlator cross-correlates r(t), with the 2

possible transmitted symbols s0(t) and s1(t)

Output for either z0 or z1 is given by

This cross-correlation process basically computes the

projection of r(t) into 2 basis functions s0(t) and s1(t)

The outputs z0 and z1 are then feed to the Threshold Detector

x

Threshold

Detector

r t

( ) s t

0

( )

t T

z T

0

( )

( )

s t

i

x

z T

1

( )

s t

1

( )

()

z dt

T

0

()

z dt

T

0

z t

0

( )

z t

1

( )

0 0

0

( ) ( ) ( )

T

z T r t s t dt

1 1

0

( ) ( ) ( )

T

z T r t s t dt

375

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Correlator-Type Receiver - 2

The detector compares z1 and z0 and decides that

1 was transmitted if z1 > z0

0 was transmitted if z1 < z0

So when s1(t) is transmitted,

PB = P[z0 > z1] = P[n0 > E + n1] = P[n0 -n1> E]

Let x = n0 - n1

2

2 2 2

0 1 0 1 0 1

2 2

0 0

0

2

2 ( ) 2

4 2

n

E x zeromean

E x E n n E n E n E n n

N N

E n t

0, orthogonal

Noise Variance

376

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-94-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

From (b):

But

At sampling instant t = T, we have

This is the same result obtained in (a)

Hence

z T z T

( ) '( )

h t s T t h t s T t s T t

( ) ( ) ( ) [ ( )] ( )

z

z t r s T t d

t

'( ) ( ) ( )

0

z t r t h t r h t d r h t d

t

'( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

z

z

0

' '

0

0

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( )

T

t T

T

T

z t z r s T T d

r s d

Correlator vs. Matched Filter - 2

397

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Examples

Example Signal to Noise Ratio

Example Correlator Output

Example Matched Filter

398

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

#Generalized One Dimensional Signals - 1

One Dimensional Signal Constellation

-A +A

so s1

M=2

0

-A +A

s1 s2

M=4

0

-3A

so

+3A

s3

-5A -3A

s1 s2

M=8

0

-7A

so

-A

s3

+3A +5A

s5 s6

+A

s4

+7A

s7

E A A A

avg

2 2

2

2

E A A A A A

avg

9 9

4

5

2 2 2 2

2

E A A A A A A A A A

avg

49 25 9 9 25 49

8

21

2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2

2

399

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Binary Baseband Orthogonal Signals

Binary Antipodal Signals

Binary Orthogonal Signals

2-Dimensional Signal Constellation

An example:

+A

+A

s1

s0

1

E A A A

avg

2 2

2

2

2

-A +A

so

s1

0

1

E A A A

avg

2 2

2

2

1( )

t

1 2 0

( ) ( )

t t dt

o

T

z

2

( )

t

1

T

T

1

T

1

T

T t

2

T

2

T

#Generalized One Dimensional Signals - 2

400

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-100-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

3. Complex Envelope (CE) Representation

Any bandpass signal can also be represented as

where g(t) = complex envelope - complex-valued signal

S(t) is convenient in many instances for analysis. Why?

Compact

Easy to manipulate without recourse to trig. identities

Relationship: Complex Envelope and M&P Forms

To transform from CE to M&P:

R(t) = |g(t)|, (t) = g(t)

To transform from M&P to CE:

g(t) = R(t)ej(t)

( ) Re ( )exp( )

c

s t g t j t

‡ Representation of Bandpass Signals

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 425

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Relationship: CE and I & Q Forms

To transform from CE to I&Q:

x(t) = Re[g(t)], y(t) = Im[g(t)]

s(t) = Re[g(t)ejt] = Re[(x(t)+jy(t)).(cosct+jsinct)]

= x(t)cosct - y(t)sinct

Relationship between Spectral Representations

Assume that

Fourier Transform (Deterministic Signals):

( ) Re ( )

j t

c

s t g t e

S f G f fc G f fc

( ) ( ) ( )

1

2

‡ Representation of Bandpass Signals

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 426

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Power Spectral Density (Random Signals):

Relationship: Power and Envelope of Bandpass

Power of bandpass signal is one half of power in

complex envelope:

G f G f f G f f

s g c g c

( ) ( ) ( )

1

4

2

(0)

1 1 1

( ) (0)

2 2 2

s s

g g

G R

g t R G

‡ Representation of Bandpass Signals

© Prof. Okey Ugweje 427

Federal University of Technology, Minna

Department of Communications Engineering

Bandpass Modulation & Demodulation - 1

Format Multiplex

Channel

Encoder

Source

Encoder

Spread

Format Demultiplex

Channel

Decoder

Source

Decoder

Despread

Performance

Measure Bits or

Symbol

To other

destinations

From other

sources

Digital

input

Digital

output

Source

bits

Source

bits

Channel

bits

Carrier and symbol

synchronization

Channel

bits

mi

l q

mi

l q

Pe

Multiple

Access

Waveforms

Multiple

Access

Modulate

Demodulate

&

Detect

428

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-107-320.jpg)

![Department of Communications Engineering

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation - 1

The most commonly used combination of amplitude

and phase signaling is the Quadrature Amplitude

Modulation (QAM)

Some books regard it as an extension of the QPSK

since it consist of two independent amplitude-

modulated carrier in quadrature. i.e.,

where ai and bi are amplitude levels obtained by

mapping k-bit sequence into amplitudes, or

where g(t) is the signal pulse shaping function

2

( ) [ cos sin ]

i i o i o

E

s t a t b t

T

( ) ( )[ cos sin ]

i i o i o

s t g t a t b t

553

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation - 2

It is sometimes regarded as M-ary APK with

constraints put on the amplitude and phase

where

In this case, both the amplitude and phase can be

varied

Any combination of M1-level amplitude and M2-level

phase can be used in the construction of QAM

1 2

2

( ) cos[ ], 1,2, , , 1,2, ,

i i o j

E

s t V t i M j M

T

1 2 2 1 2

2 , 2 , log ,

m n

M M m n M M

b

s

R

R

m n

554

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Any combination of M1-level amplitude and M2-level

phase can be used in the construction of QAM

QAM waveform can be represented as a linear

combination of 2 orthogonal signals 1(t) and 2(t)

where

In vector notation:

1 2

( ) ( ) ( )

i i i

s t A t B t

1 2

2 2

( ) cos[ ], ( ) sin[ ]

o o

T T

s s

t t t t

1 2

, , ,

i i i i i i i

s s s A E B E a b

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation - 3

555

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje

Department of Communications Engineering

Using the vector representation, we can realize an L-

by-L matrix representing the coordinates of (ai, bi)

where

( 1, 1) ( 3, 1) ( 1, 1)

( 1, 3) ( 3, 3) ( 1, 3)

{ , }

( 1, 1) ( 3, 1) ( 1, 1)

L L L L L L

L L L L L L

a b

i i

L L L L L L

L M

Quadrature Amplitude Modulation - 4

556

Federal University of Technology, Minna

© Prof. Okey Ugweje](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/digital-communication-230215092539-7dc58e08/85/Digital-communication-pdf-139-320.jpg)