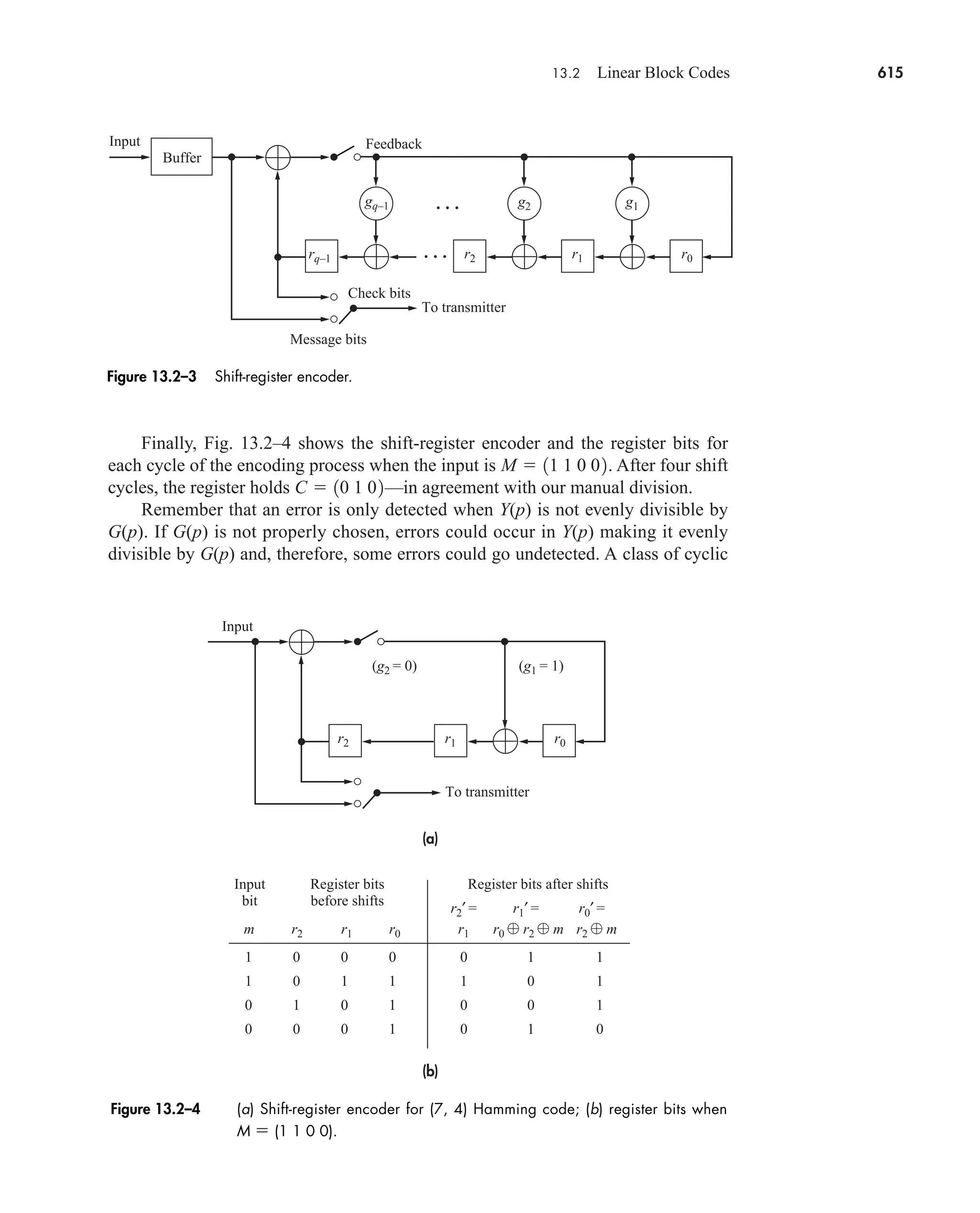

The document is the fifth edition of 'Communication Systems: An Introduction to Signals and Noise in Electrical Communication' by A. Bruce Carlson and Paul B. Crilly, published by McGraw-Hill. It covers various topics in communication systems, including signal theory, modulation, transmission, noise, and digital communication techniques. The book serves as a comprehensive resource for understanding the principles and developments in electrical communication.

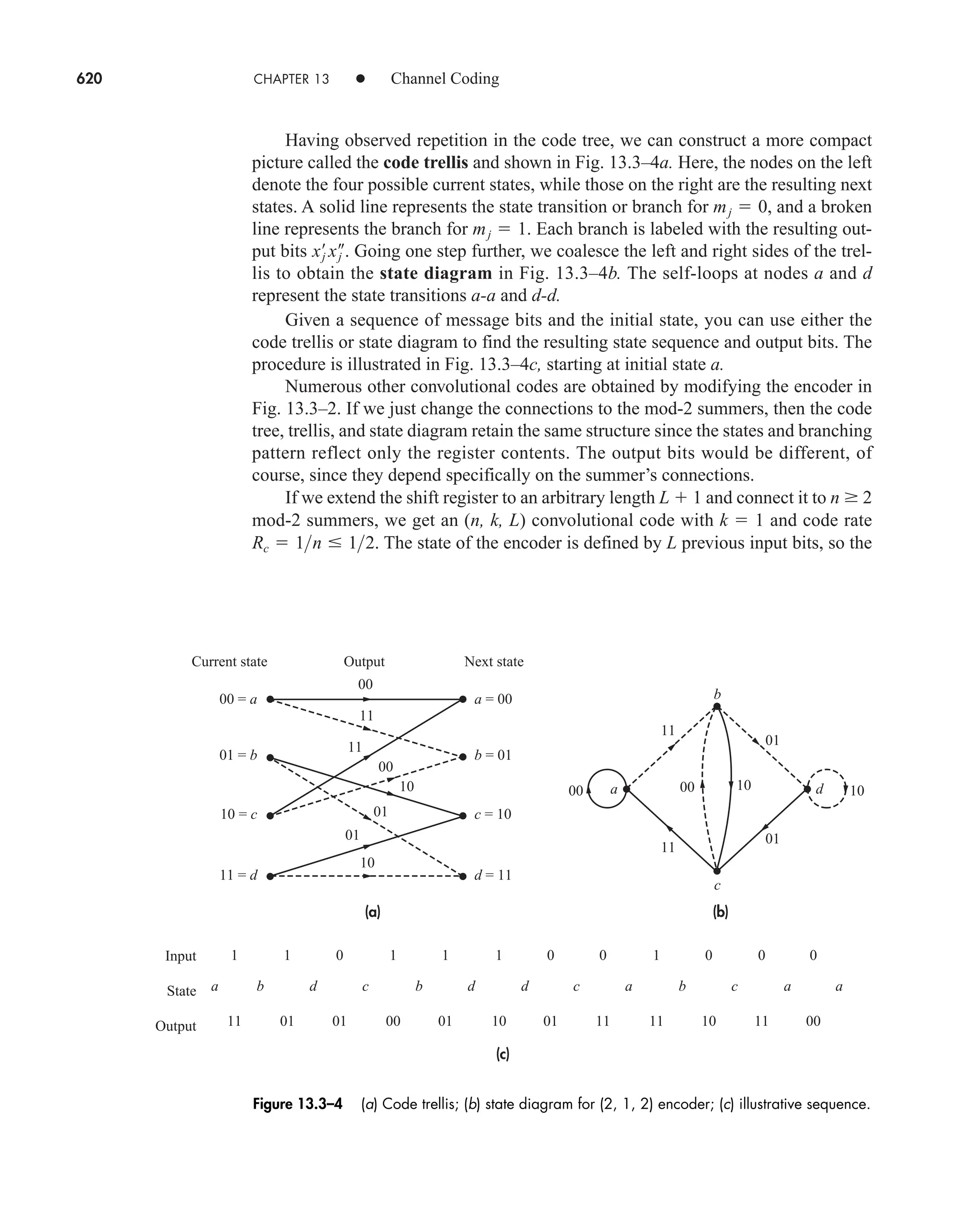

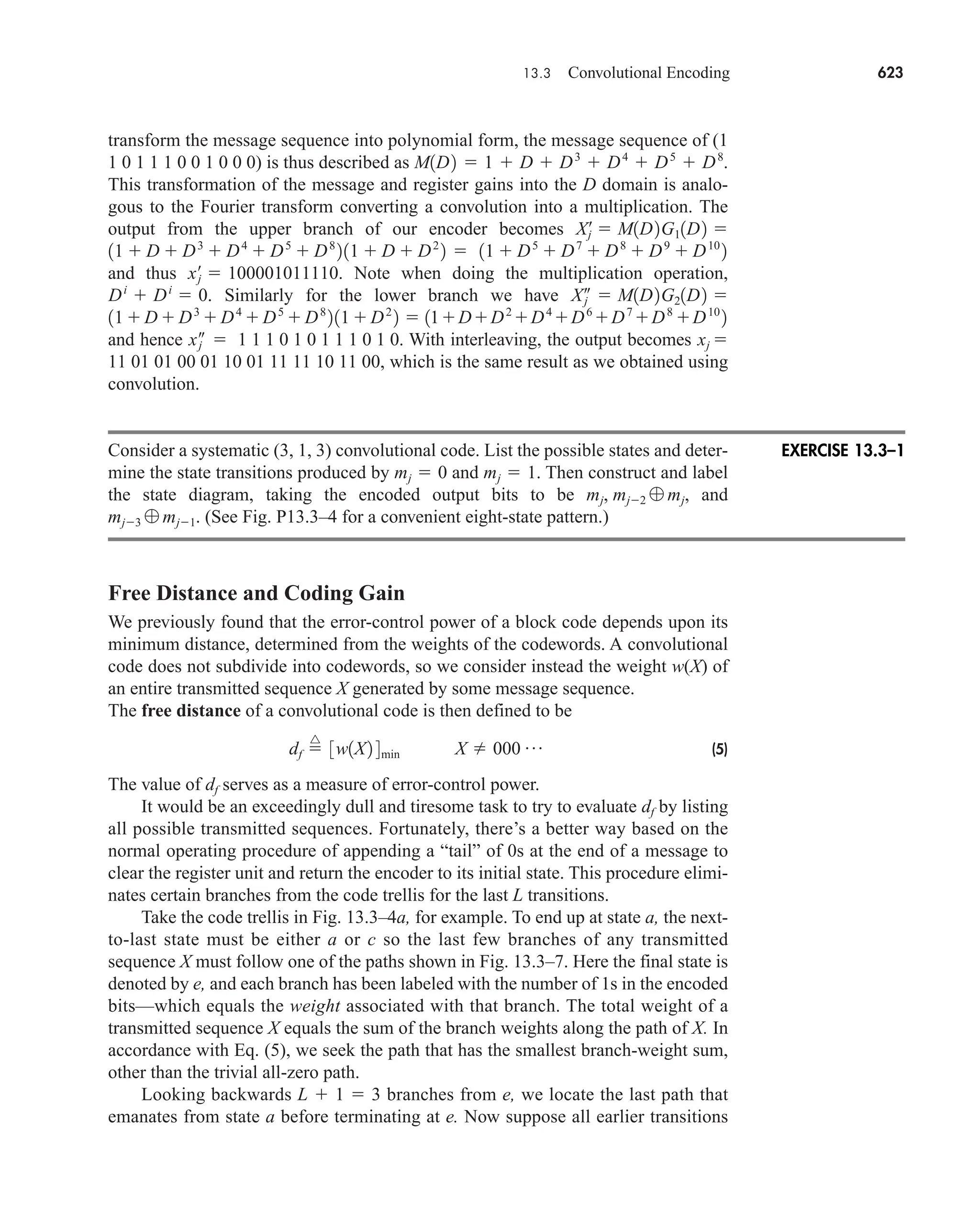

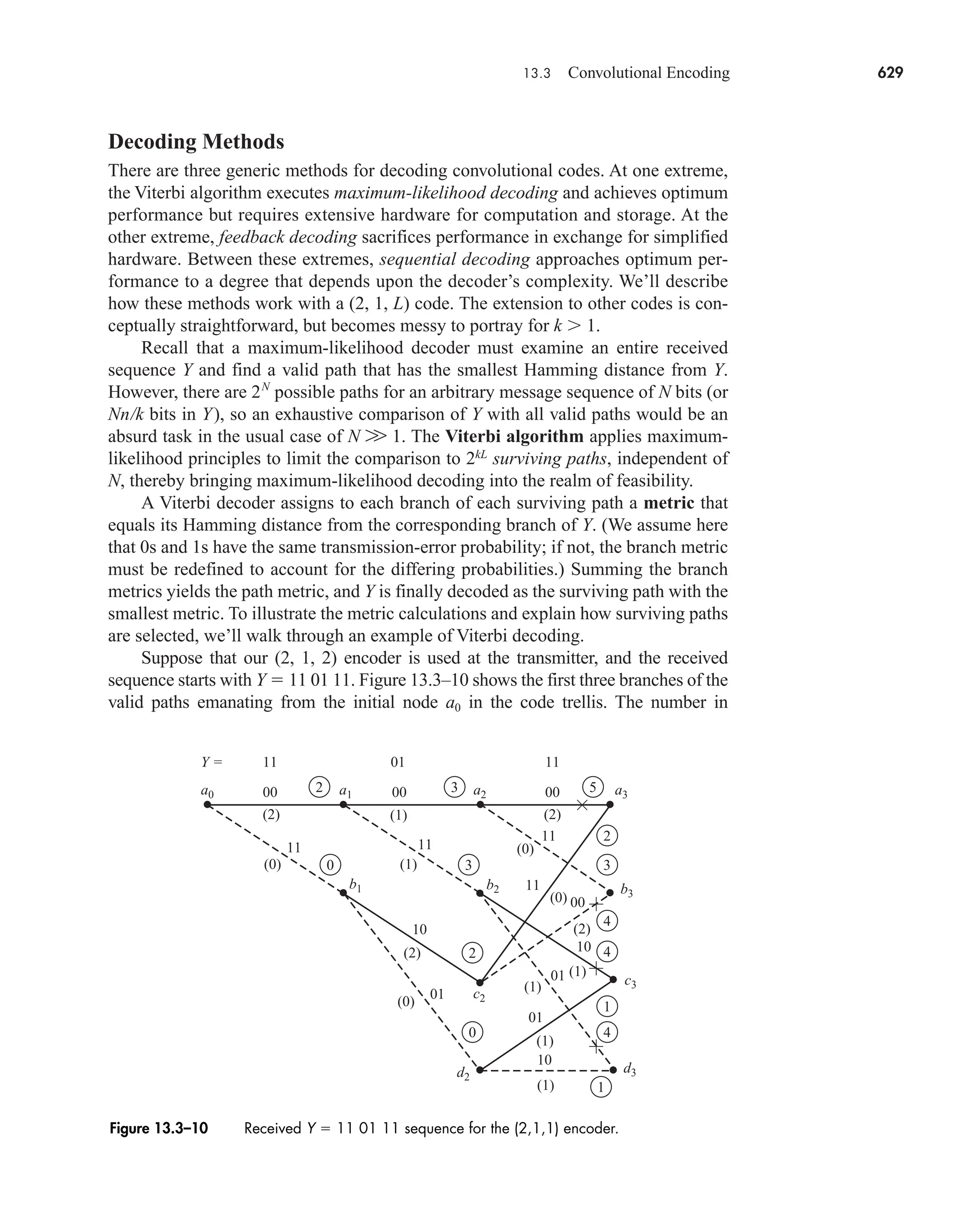

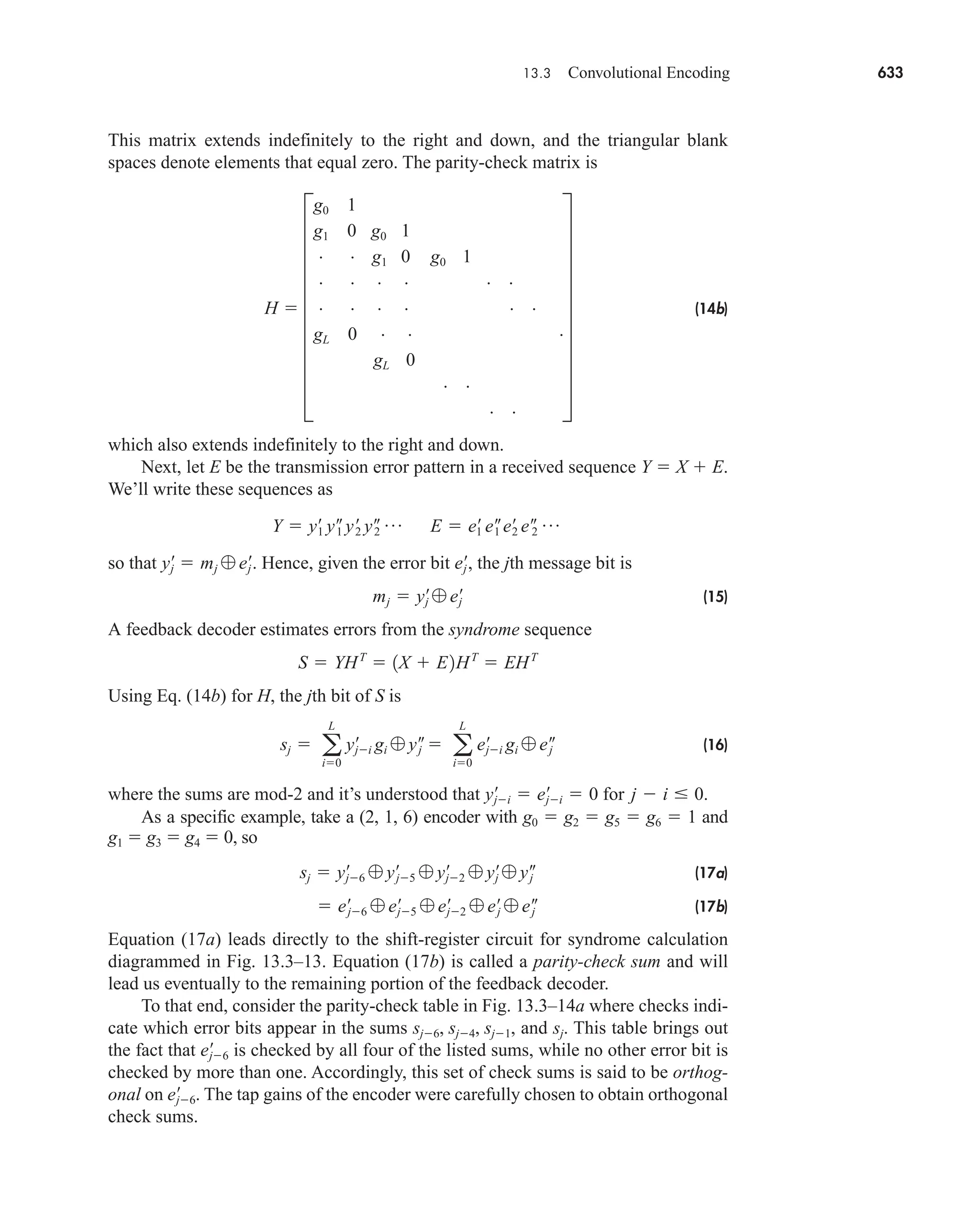

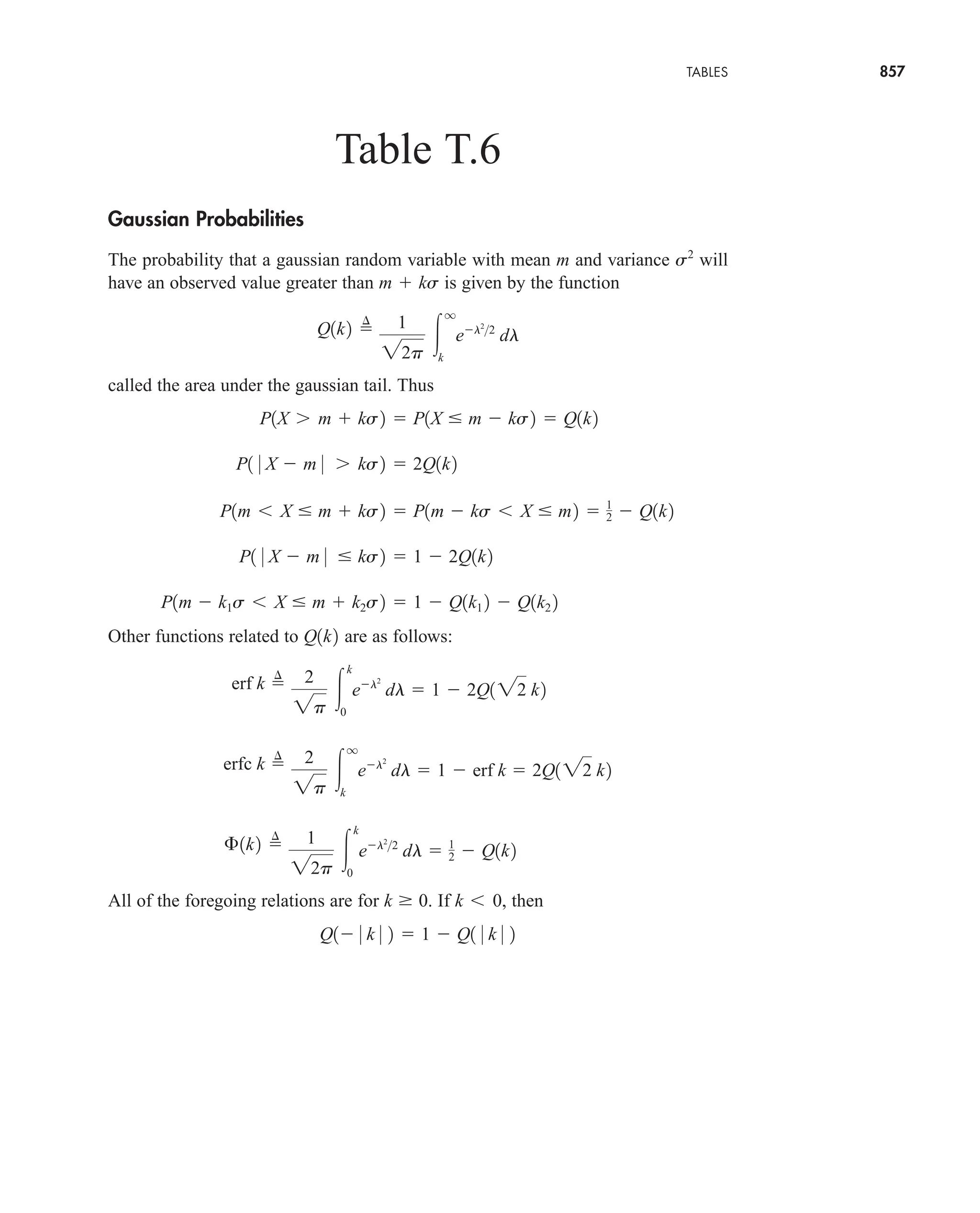

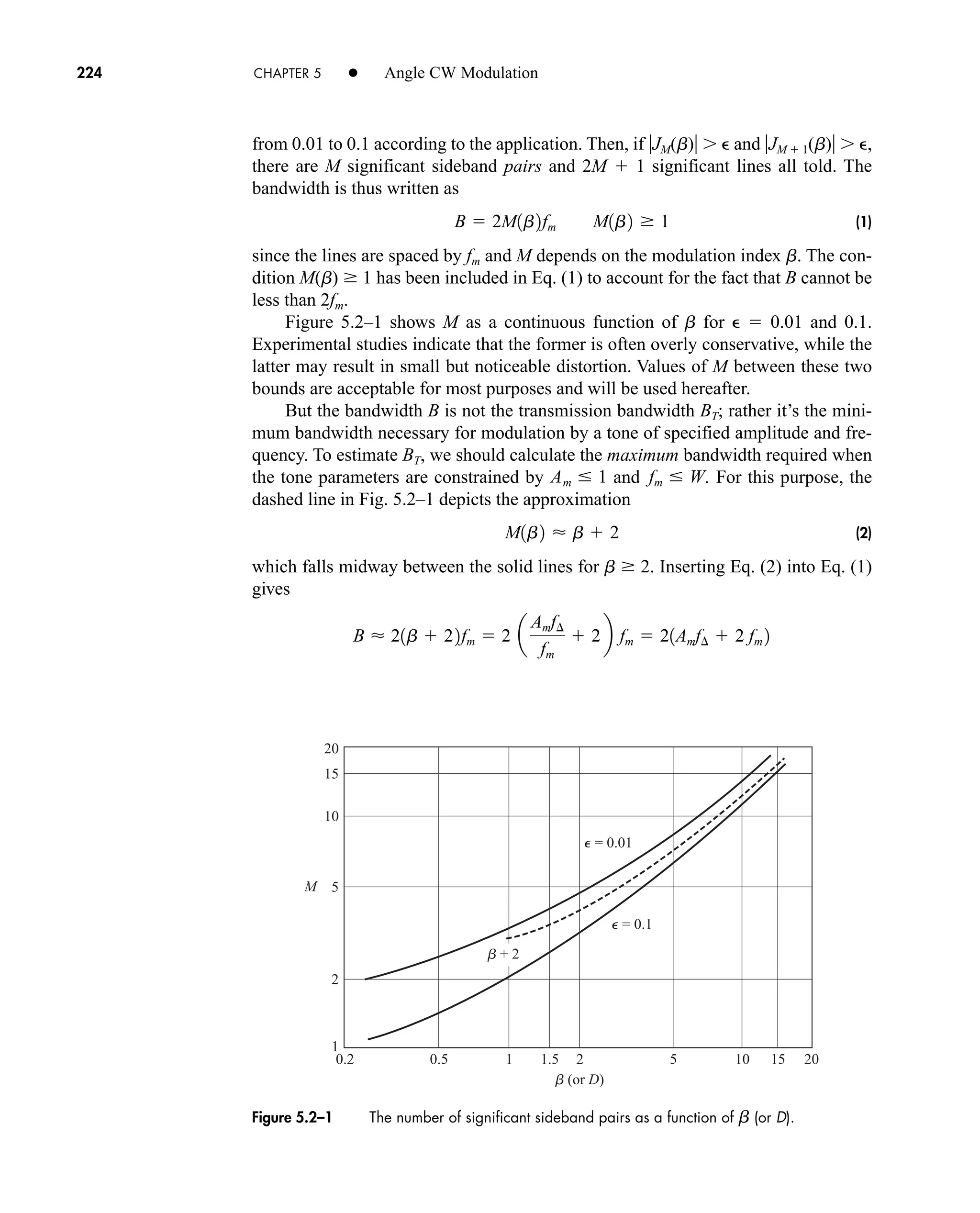

![xvii

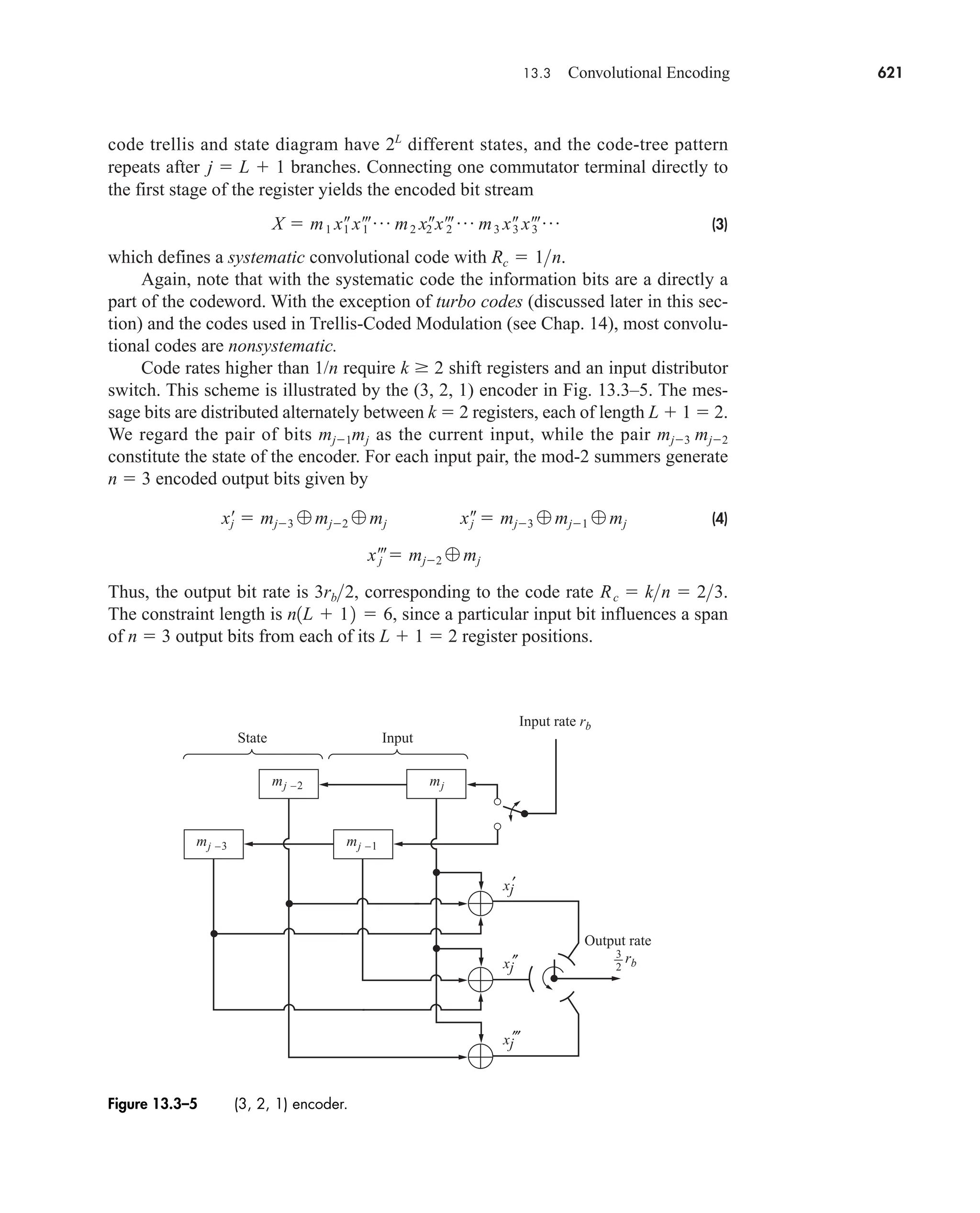

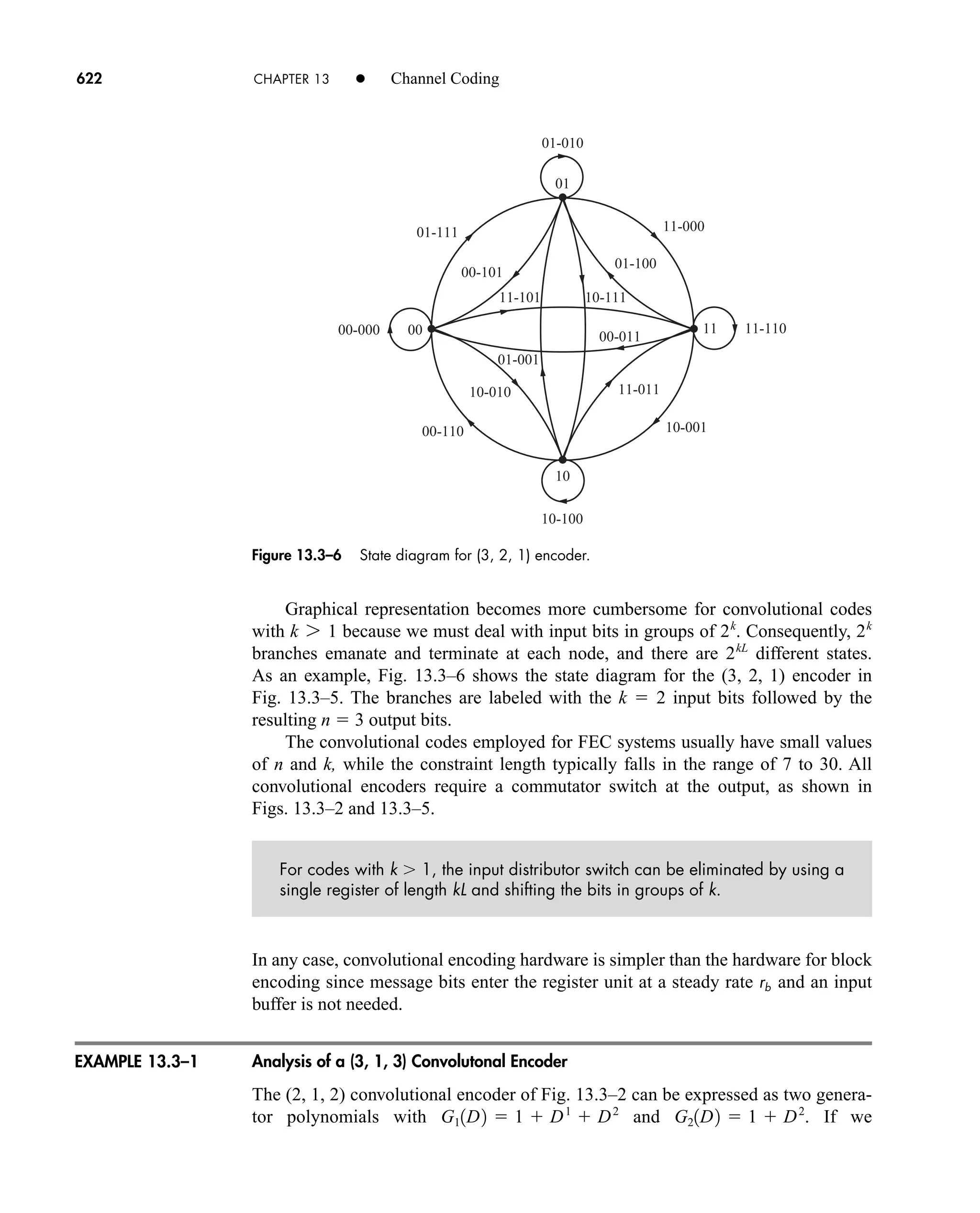

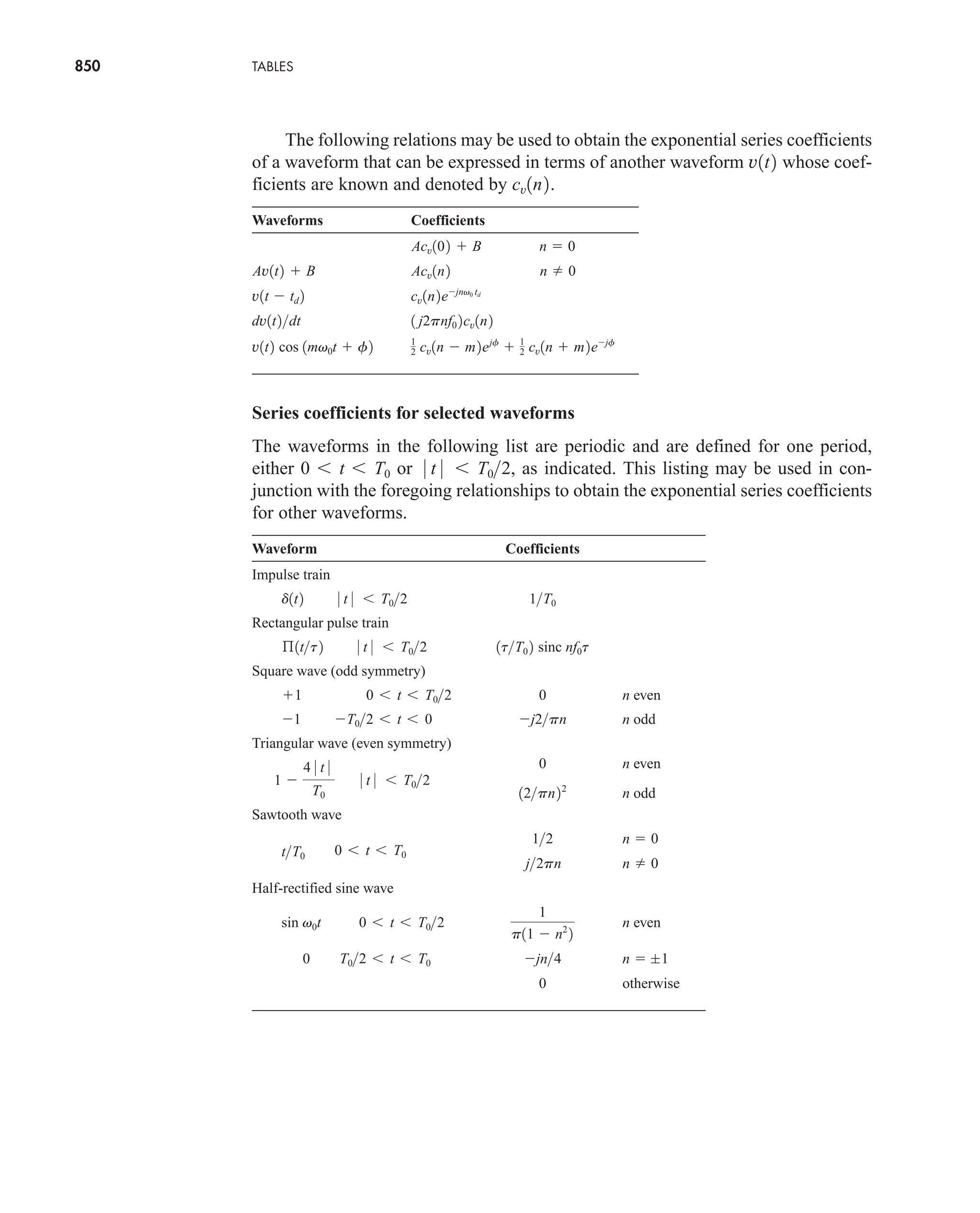

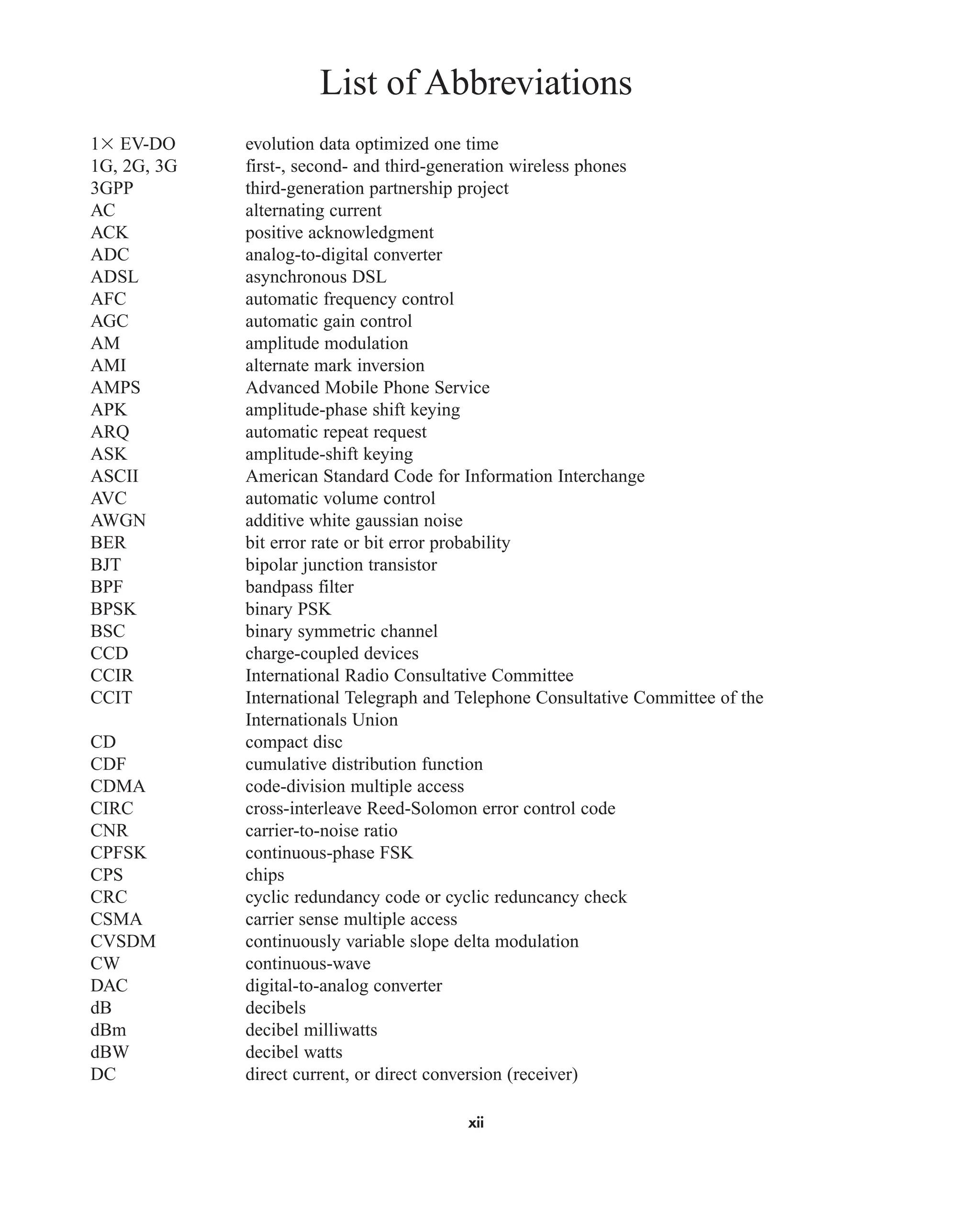

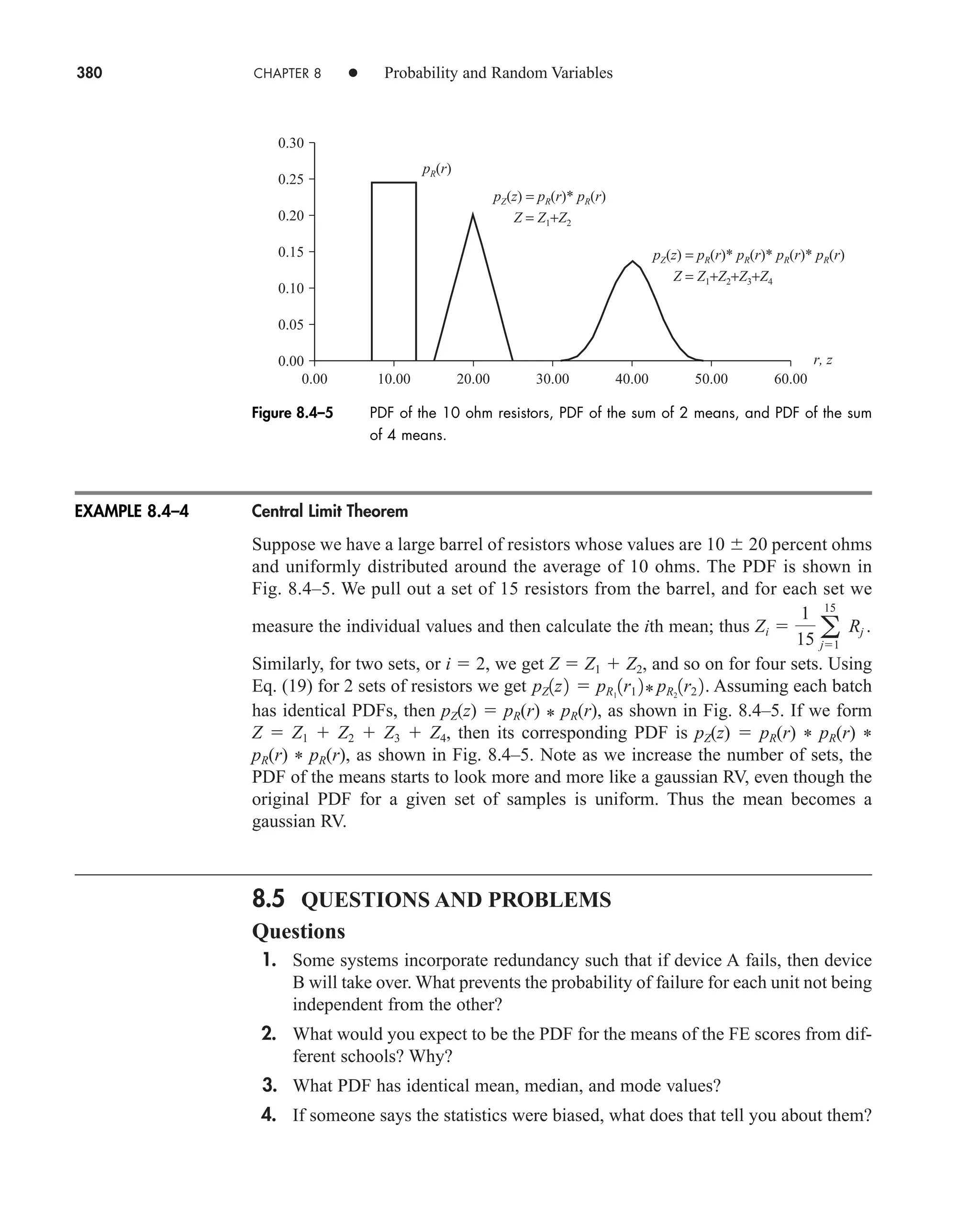

Mathematical Symbols

A, Ac amplitude constant and carrier amplitude constant

Ae aperture area

Am tone amplitude

Av(t) envelope of a BP signal

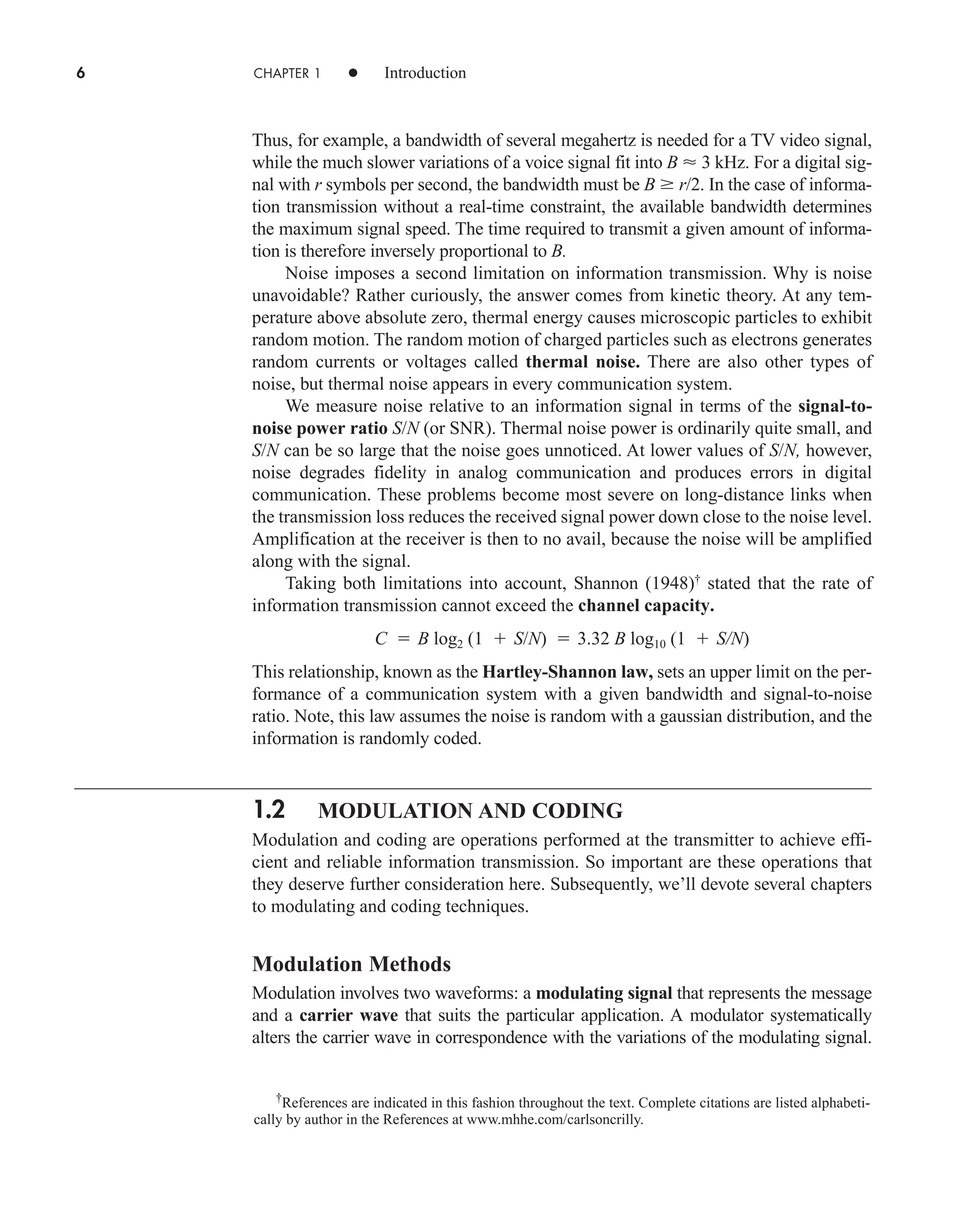

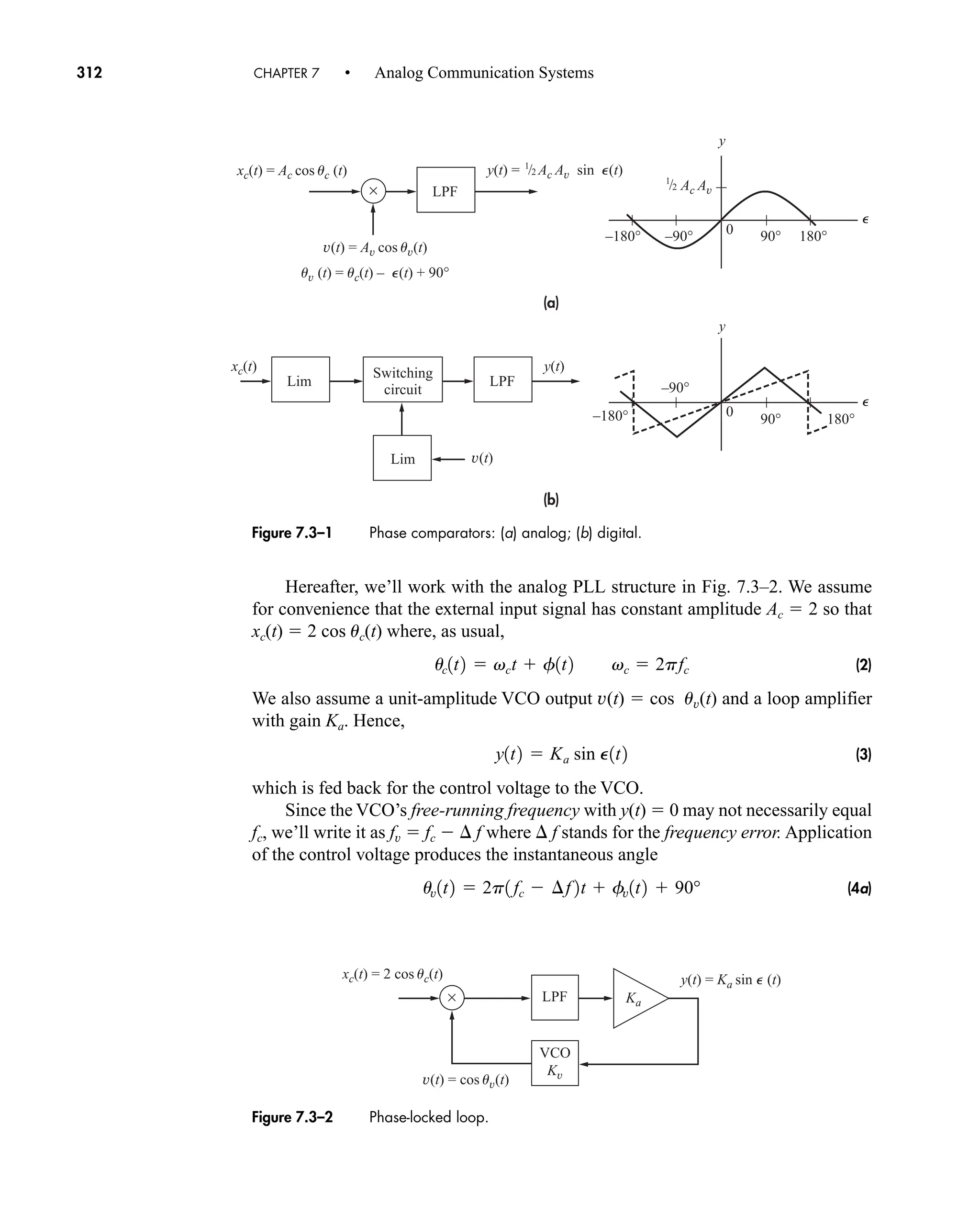

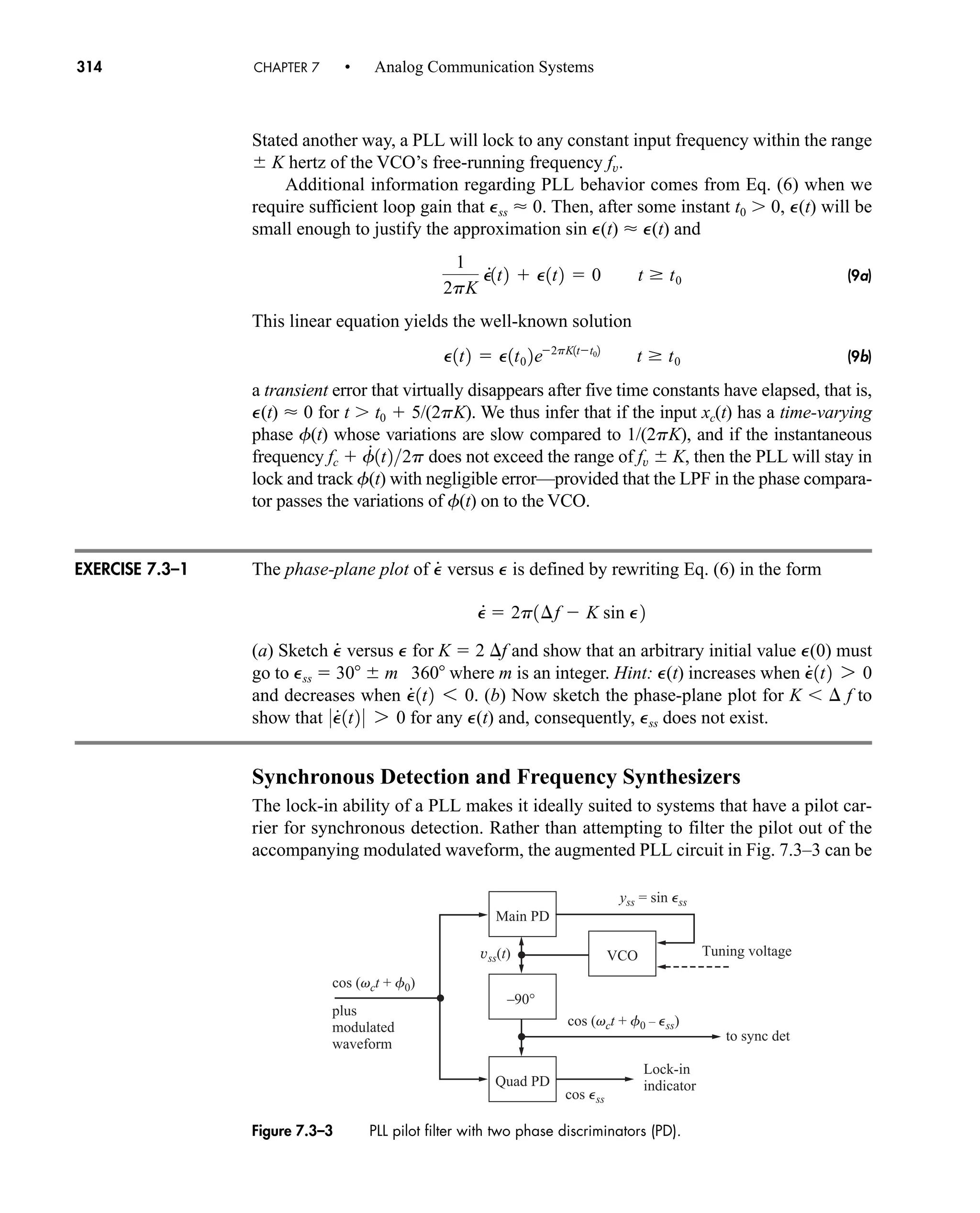

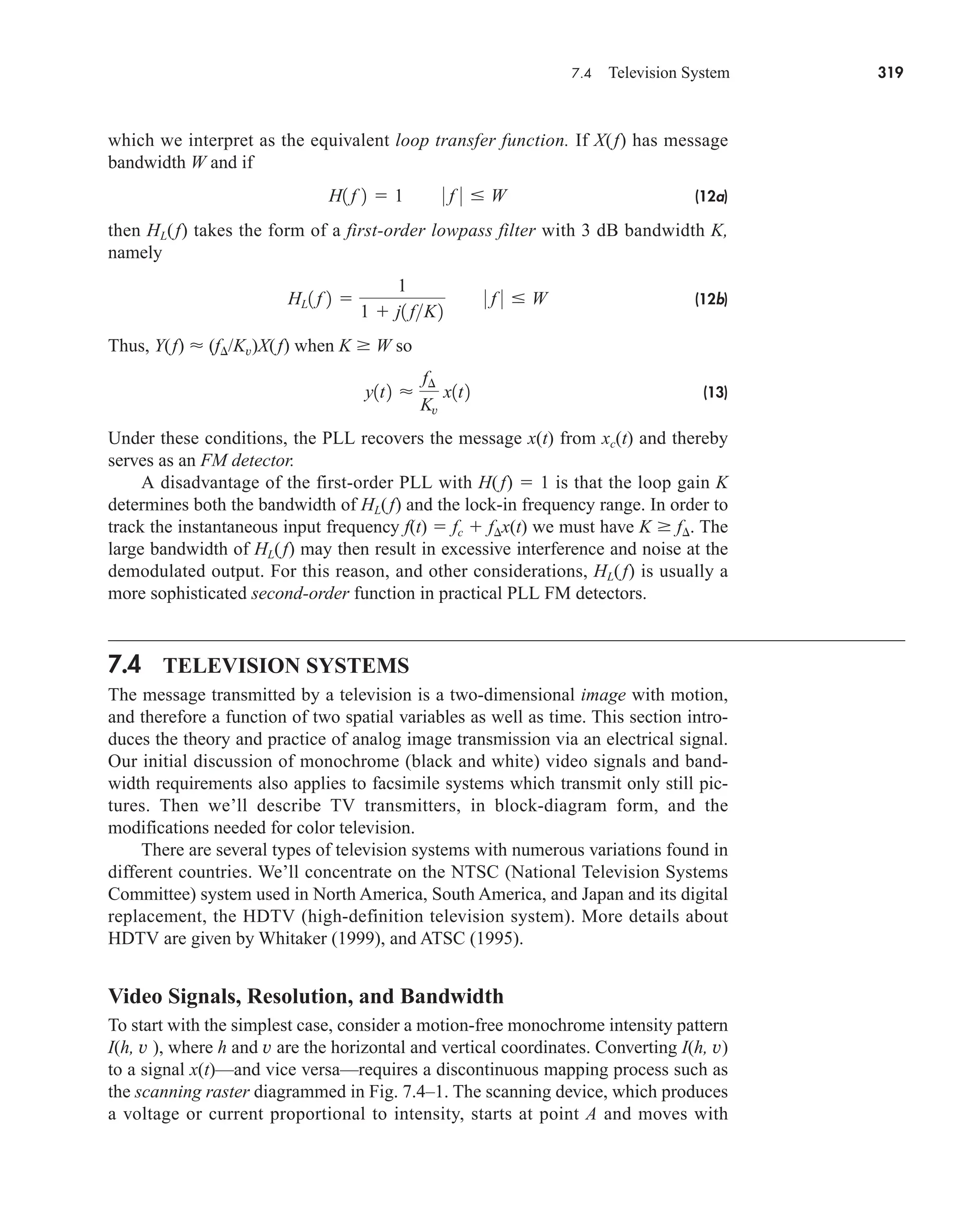

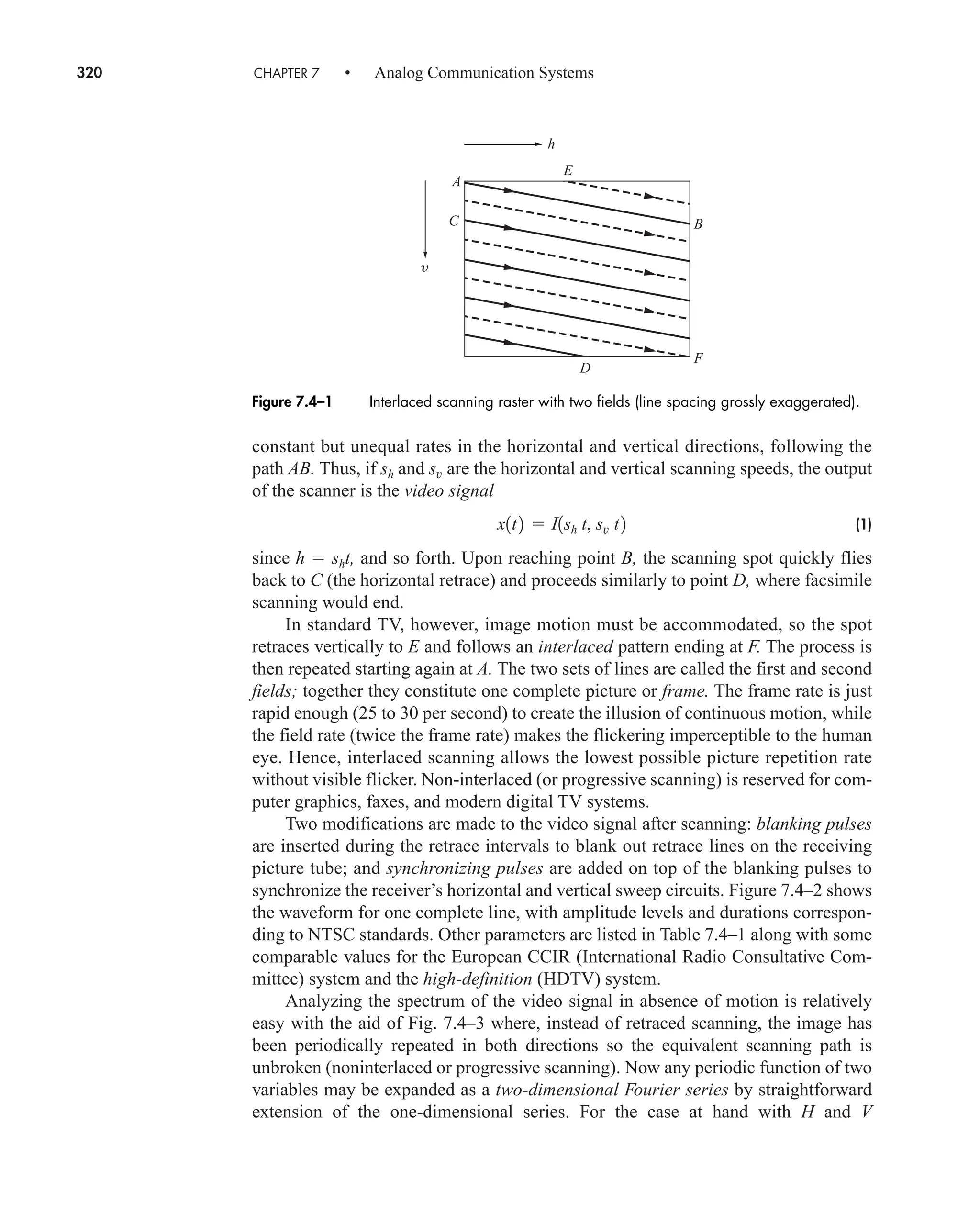

B bandwidth in hertz (Hz)

BT transmission bandwidth, or bandwidth of a bandpass signal

C channel capacity, bits per second, capacitance in Farads, or check vector

Cvw(t1, t2) covariance function of signals v(t) and w(t)

D deviation ratio, or pulse interval

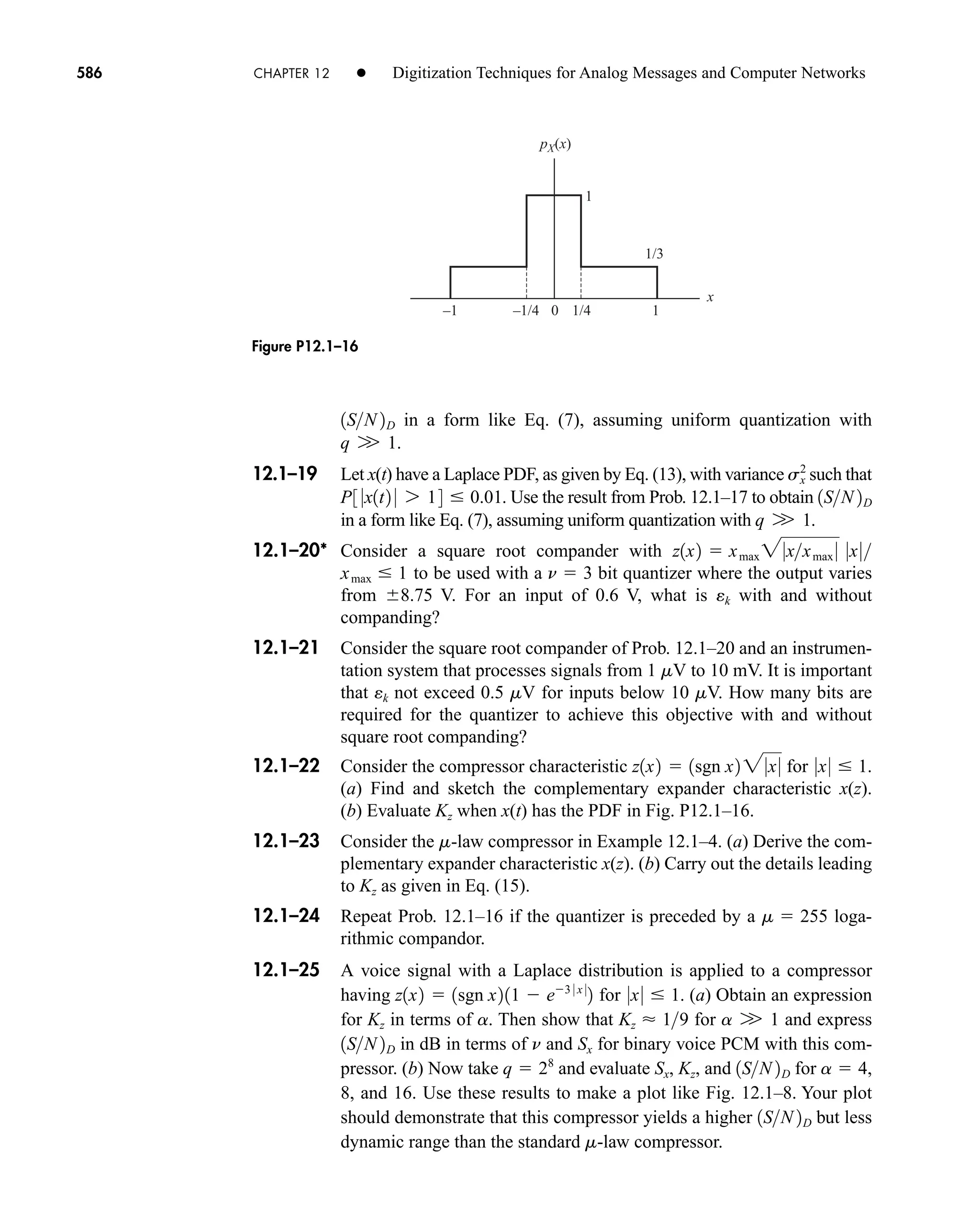

DR dynamic range

DFT[ ], IDFT[ ] discrete and inverse discrete Fourier transorm

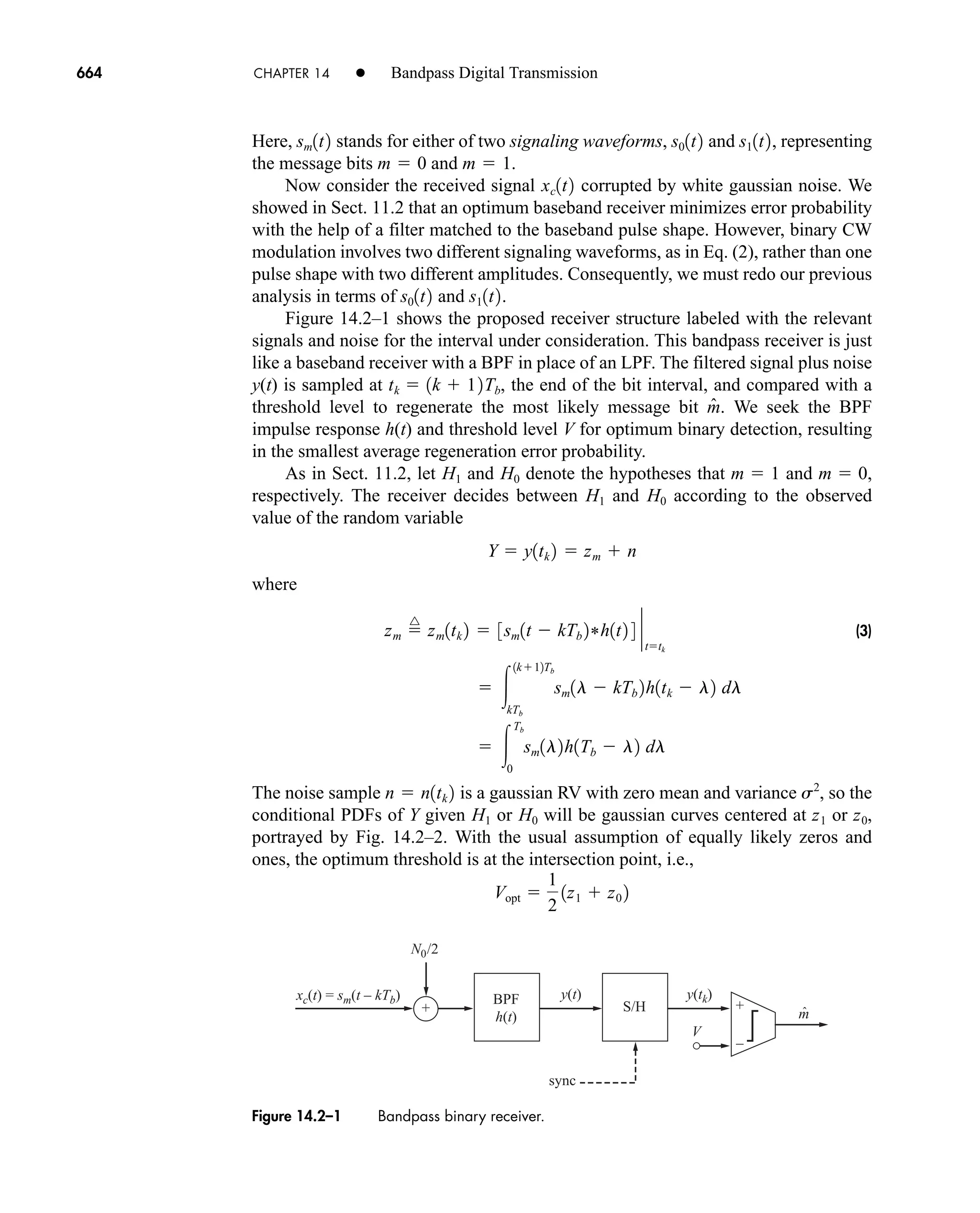

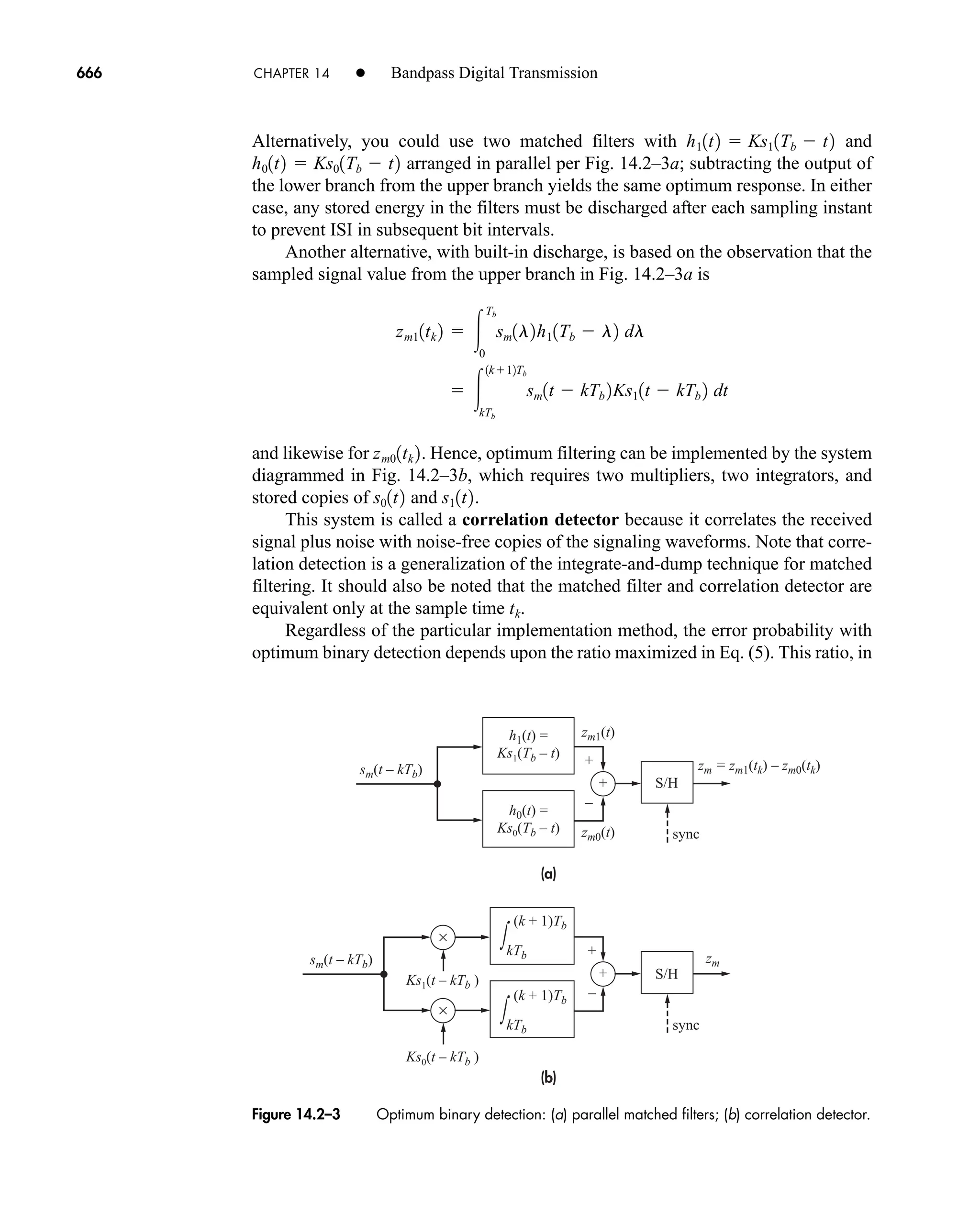

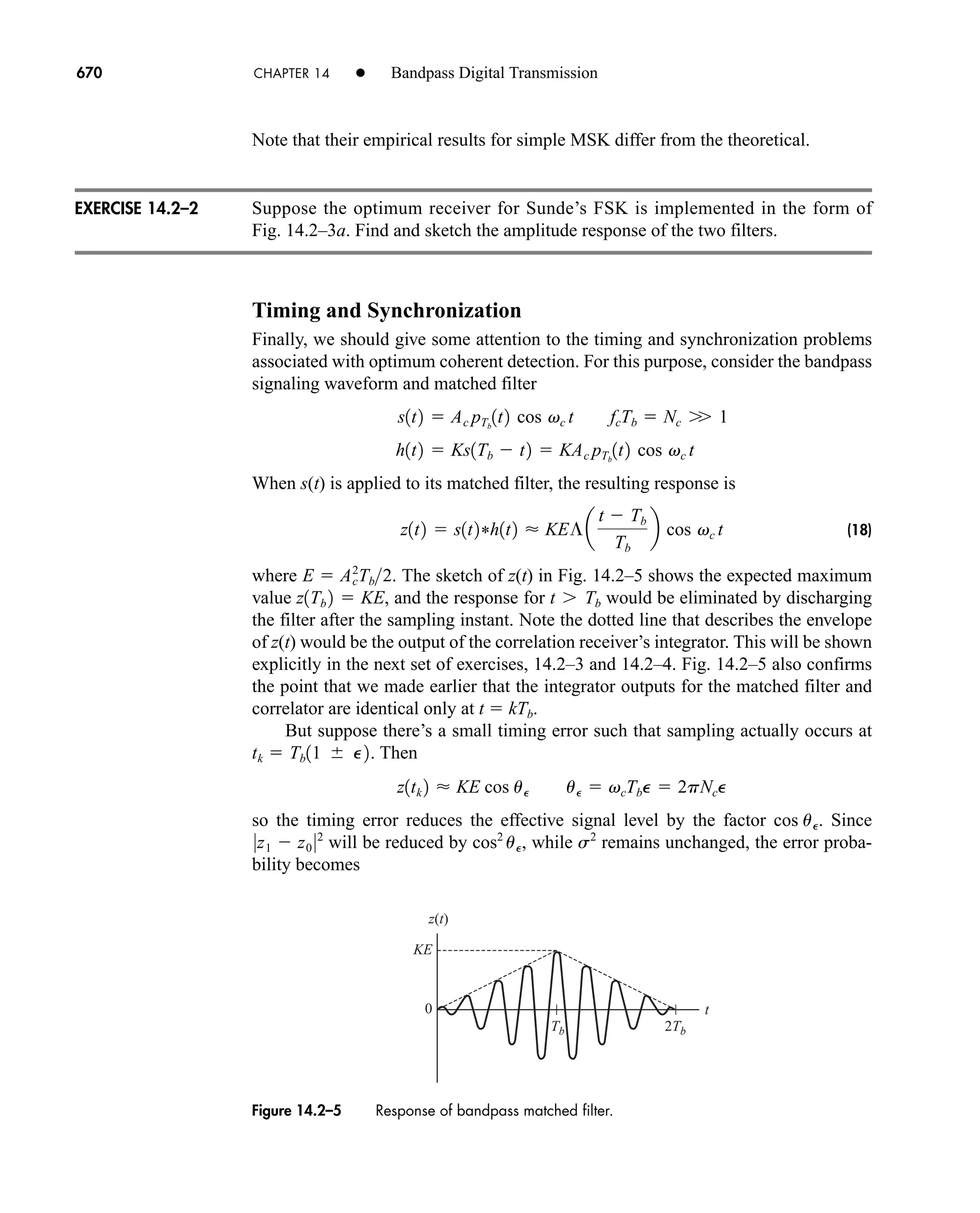

E error vector

E, E1, E0, Eb signal energy, energy in bit 1, energy in bit 0, and bit energy

E[ ] expected value operator

FX(x) cumulative distribution function of X

FXY(x,y) joint cumulative distribution of X and Y

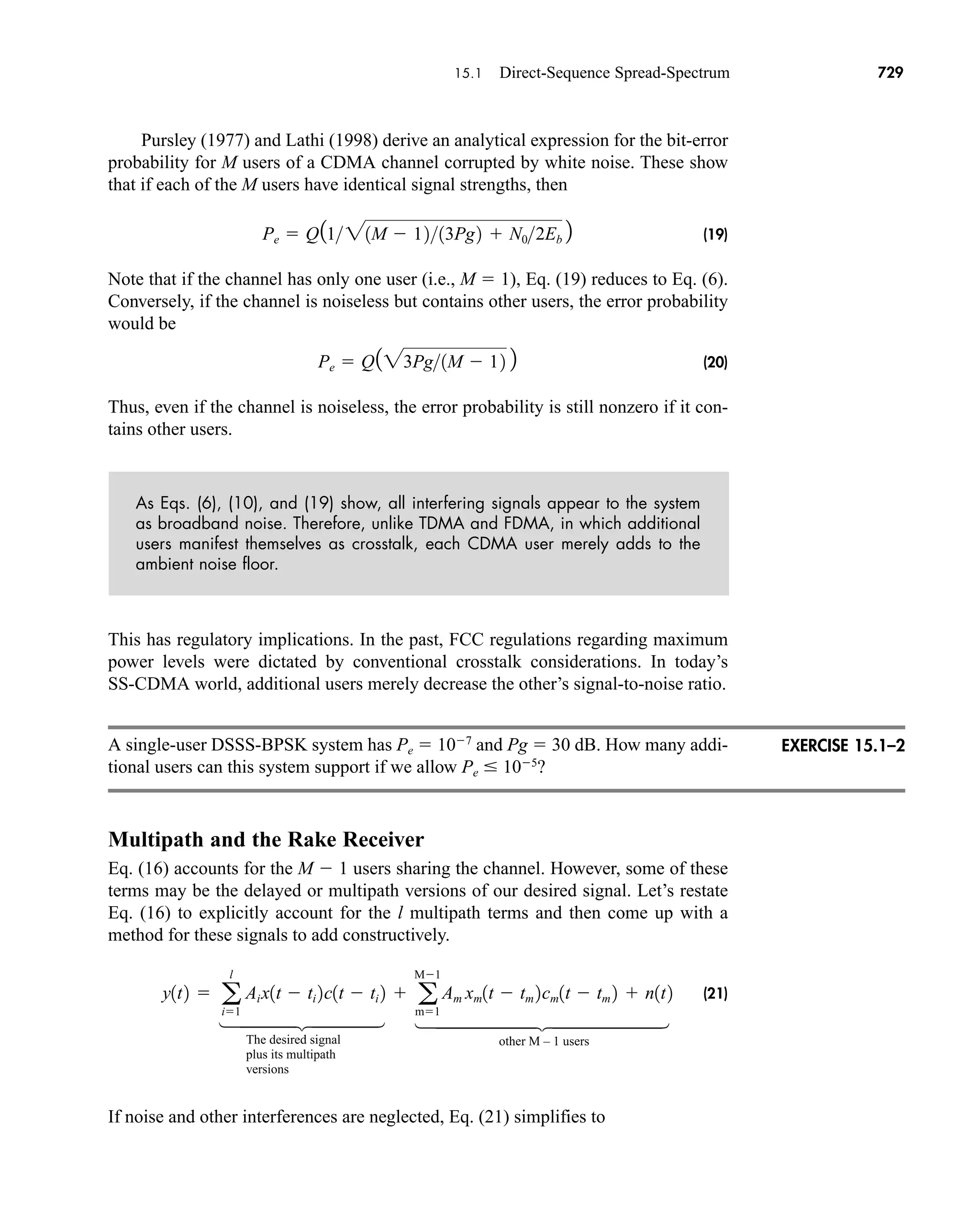

G generator vector

Gx(f) power spectral density of signal x(t)

Gvw(f) cross-spectral density functions of signals v(t), w(t)

H(f) transfer or frequency-response function of a system

HC(f) channel’s frequency response

Heq(f) channel equalizer frequency response

HQ(f) transfer function of quadrature filter

IR image rejection

Jn(b) Bessell function of first kind, order n, argument b

L,LdB loss in linear and decibel units

Lu, Ld uplink and downlink losses

M numerical base, such that q Mv

or message vector

ND destination noise power

NR received noise power

N0 power spectral density or spectral density of white noise

NF, or F noise figure

N(f) noise signal spectrum

P power in watts

Pc unmodulated carrier power

P(f) pulse spectrum

Pe, Pe0, Pe1 probability of error, probability of zero error, probability of 1 error

Pbe, Pwe probability of bit and word errors

Pout, Pin output and input power (watts)

PdBW, PdBmW power in decibel watts and milliwatts

Psb power per sideband

P(A), P(i,n) probability of event A occurring and probability of i errors in n-bit word

Q[ ] gaussian probability function

car80407_fm_i-xx.qxd 9/1/09 8:59 AM Page xvii](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-19-2048.jpg)

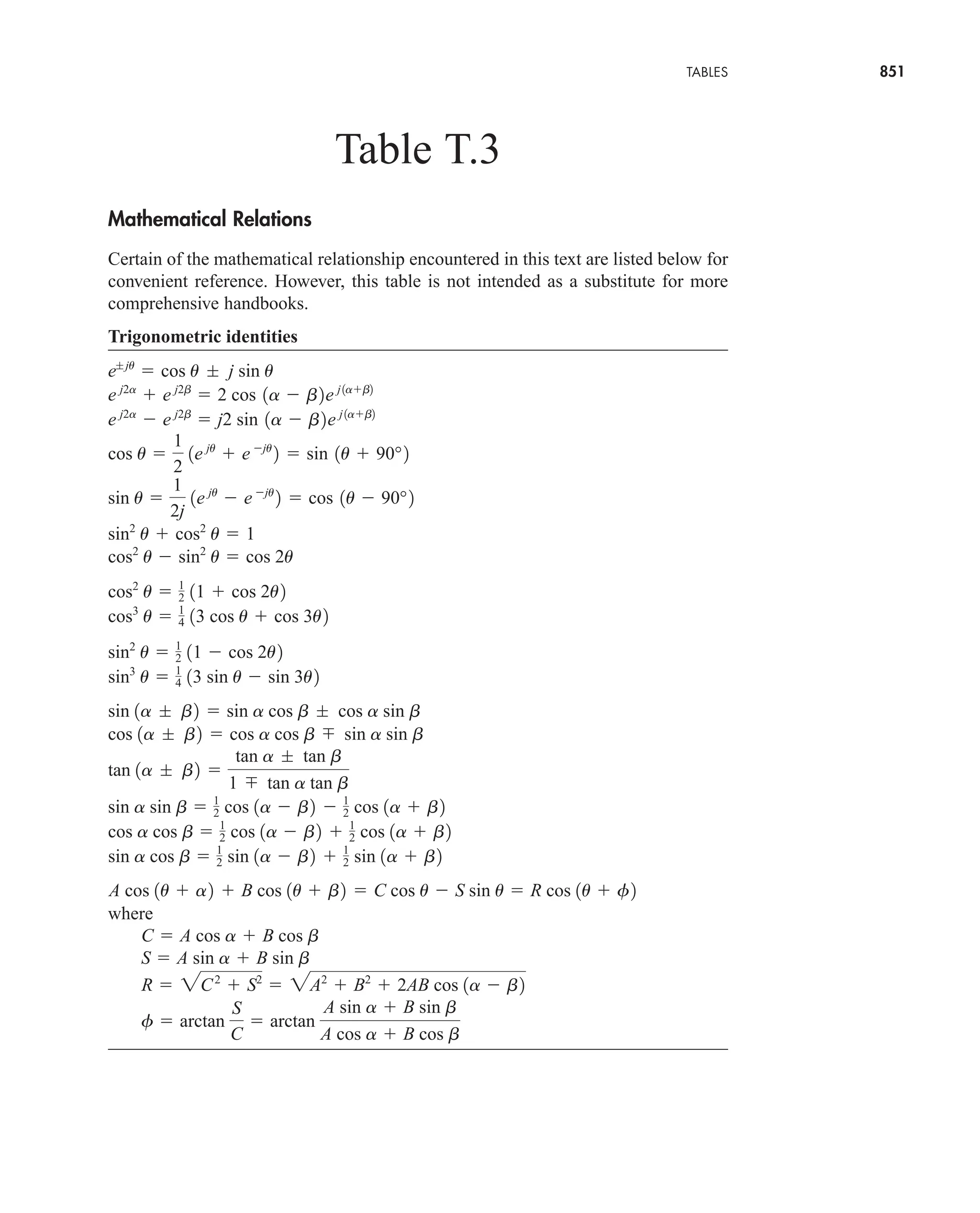

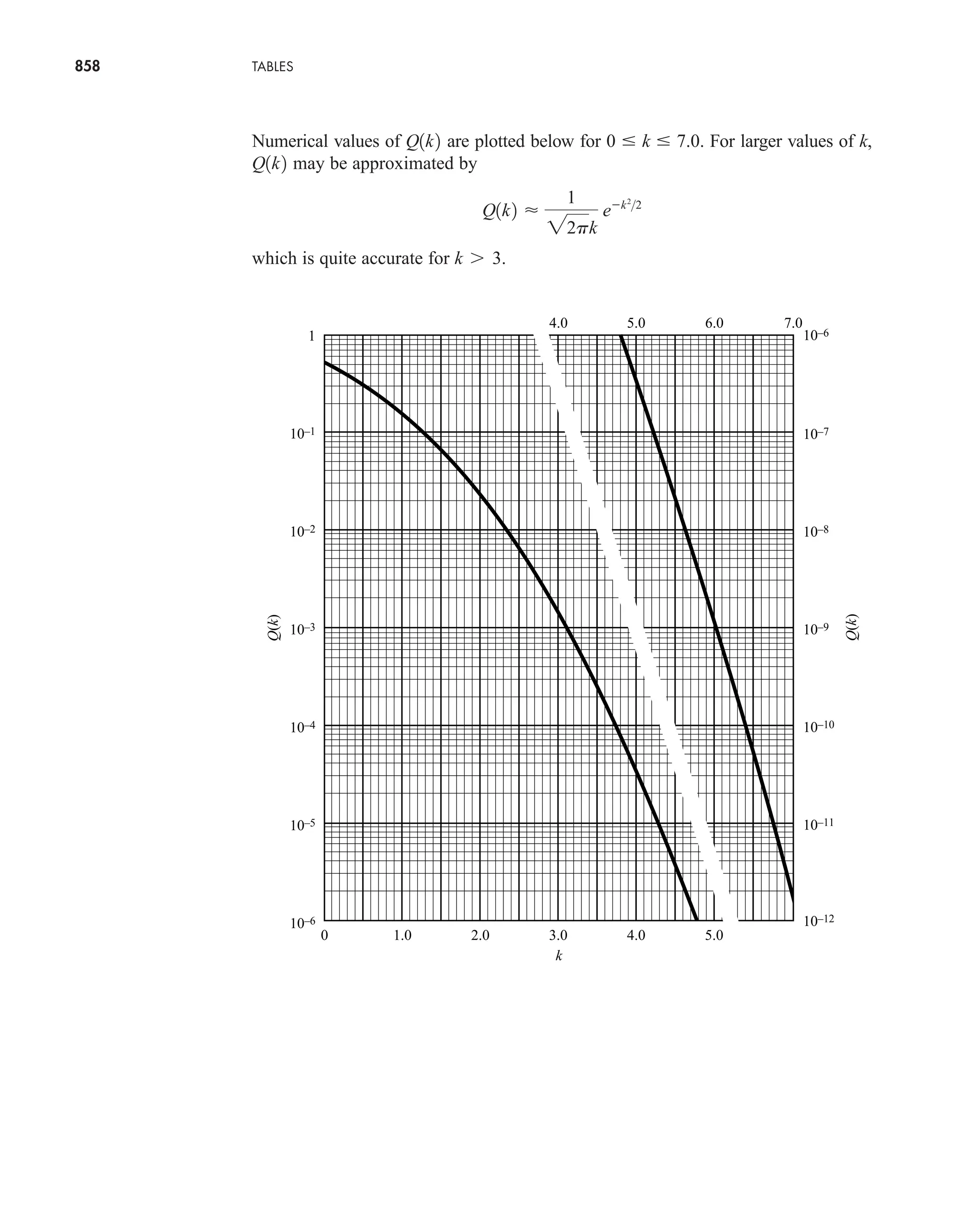

![Mathematical Symbols xix

Mathematical Symbols xix

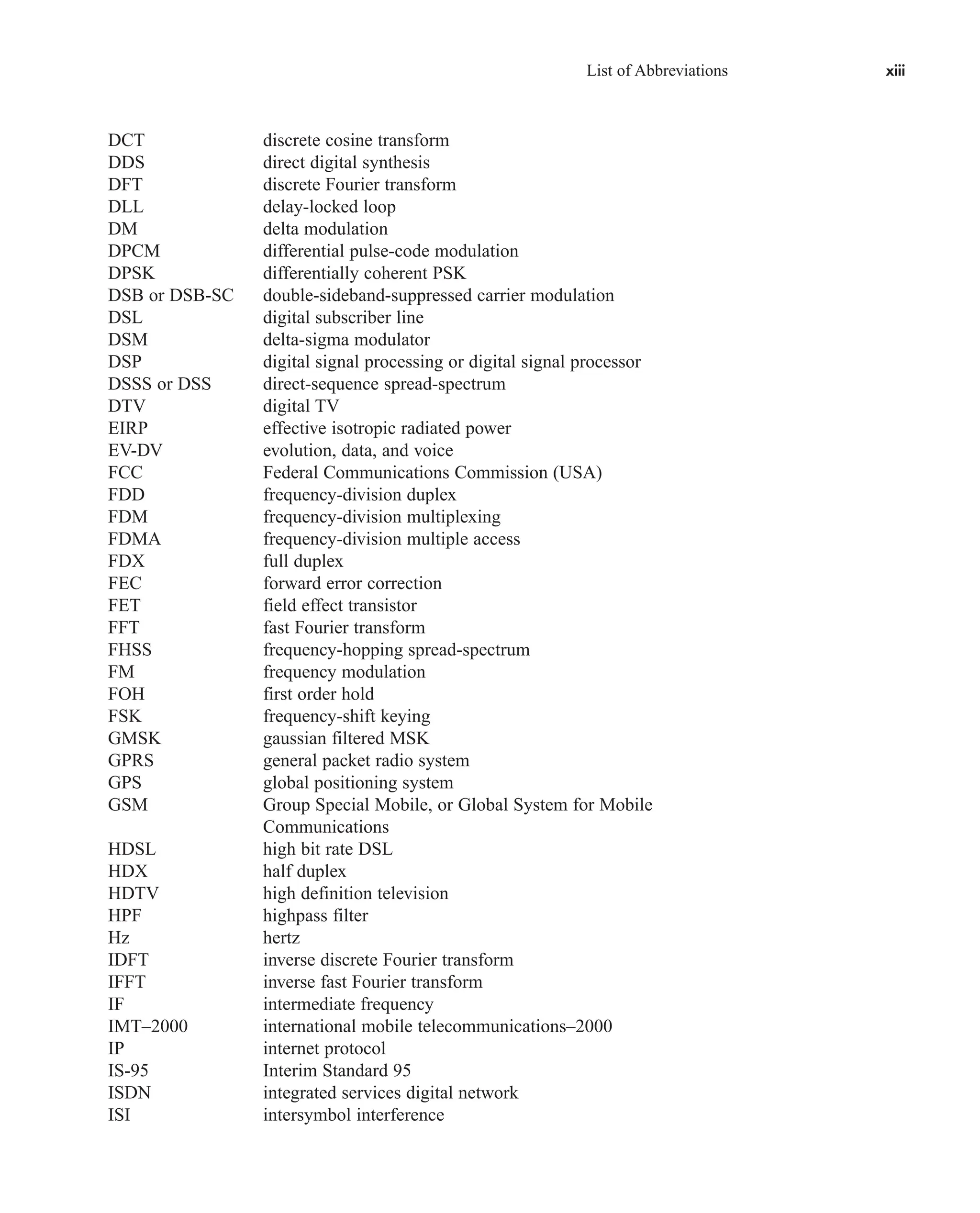

h(t) impulse-response function of a system

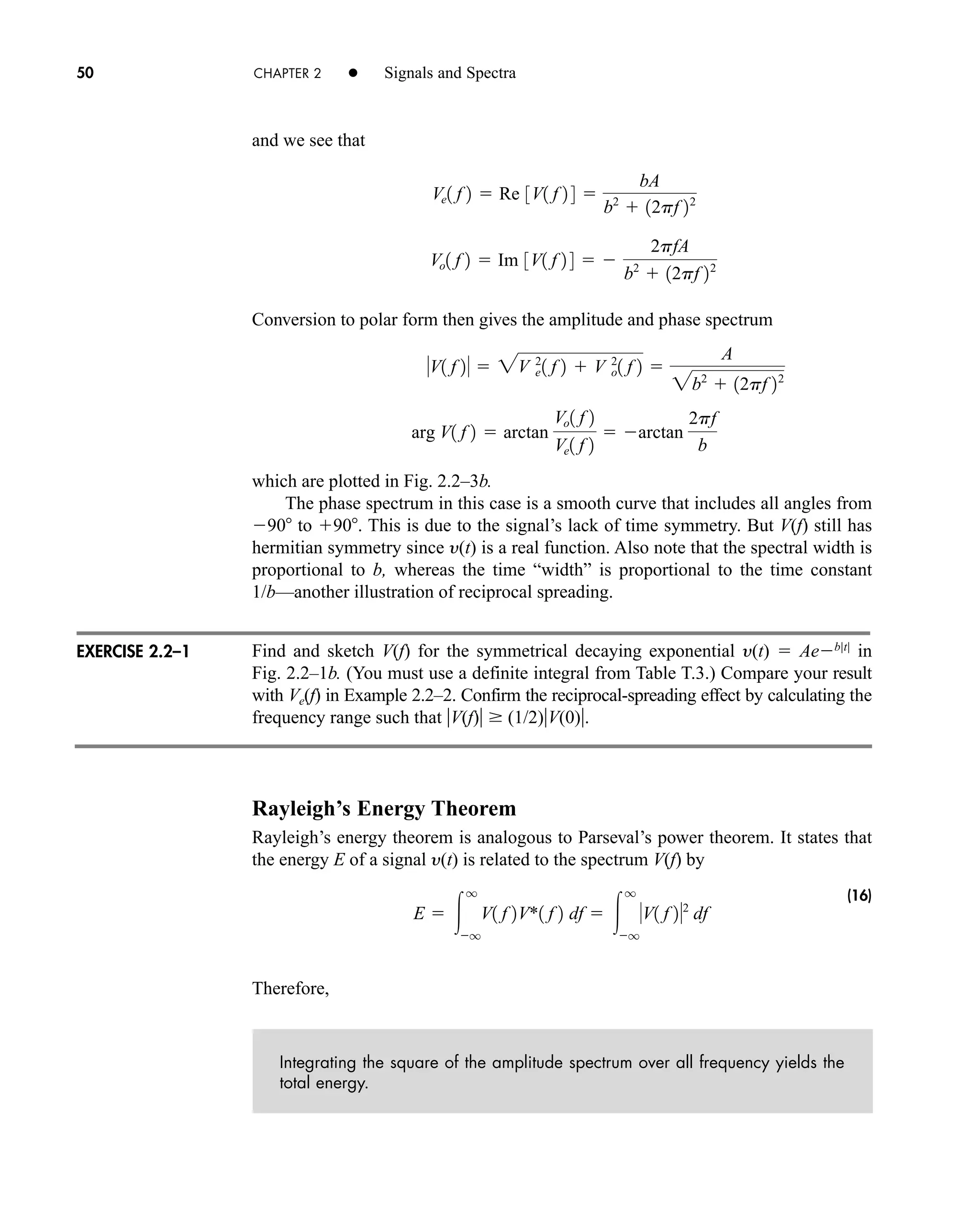

hC(t) impulse-response function of a channel

hk(t), hk(n) impulse-response function of kth portion of subchannel

hQ(t) impulse-response function of a quadrature filter

Im[x] and Re[x] imaginary and real components of x

j imaginary number operator

l length in kilometers

m number of repeater sections

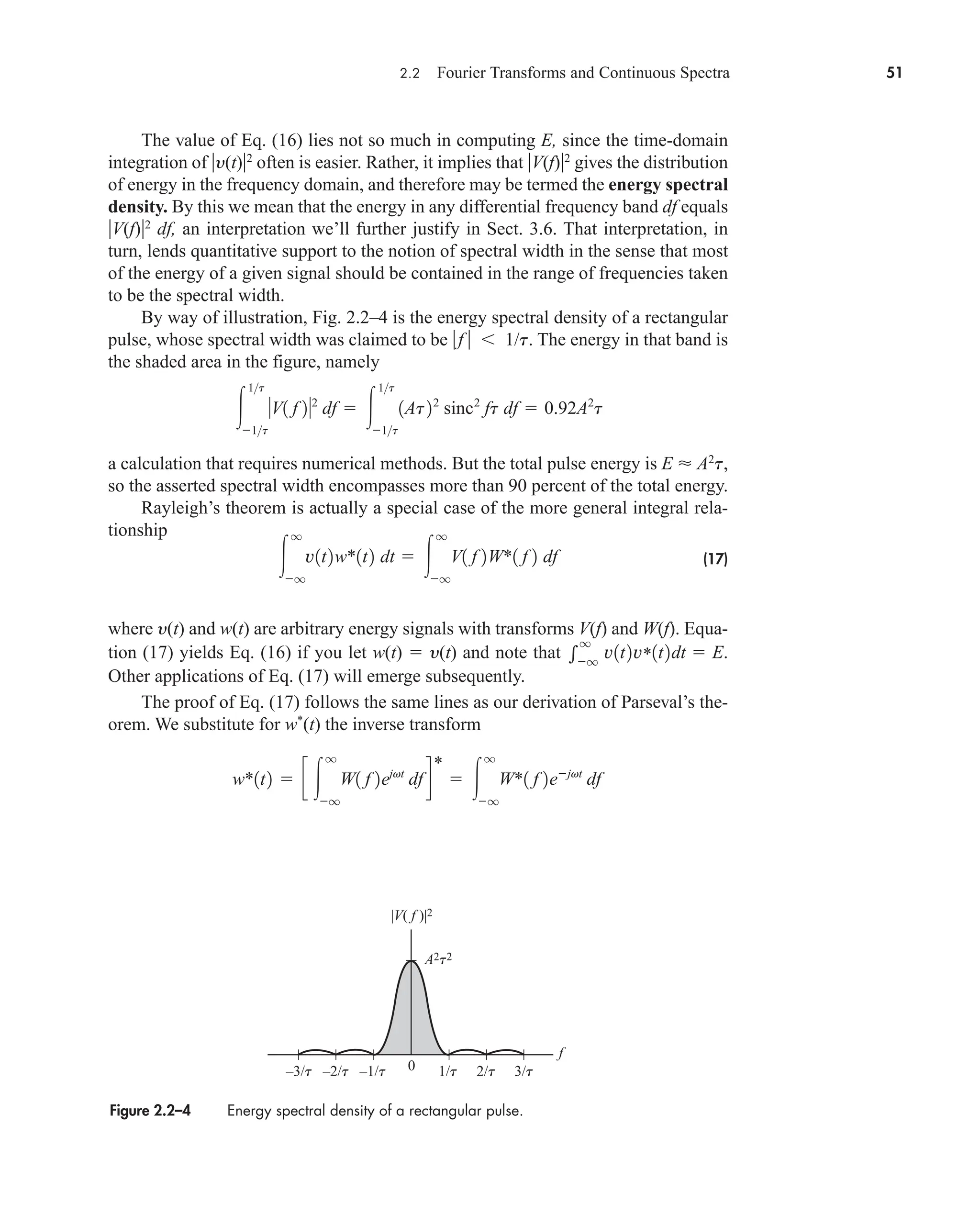

mk, k actual and estimated k message symbol

n(t) noise signal

p(t) pulse signal

p0

(t), p1

(t) gaussian and first-order monocycle pulses

output of transversal filter’s nth delay element

input to equalizing filter

peq(tk) output of an equalizing filter

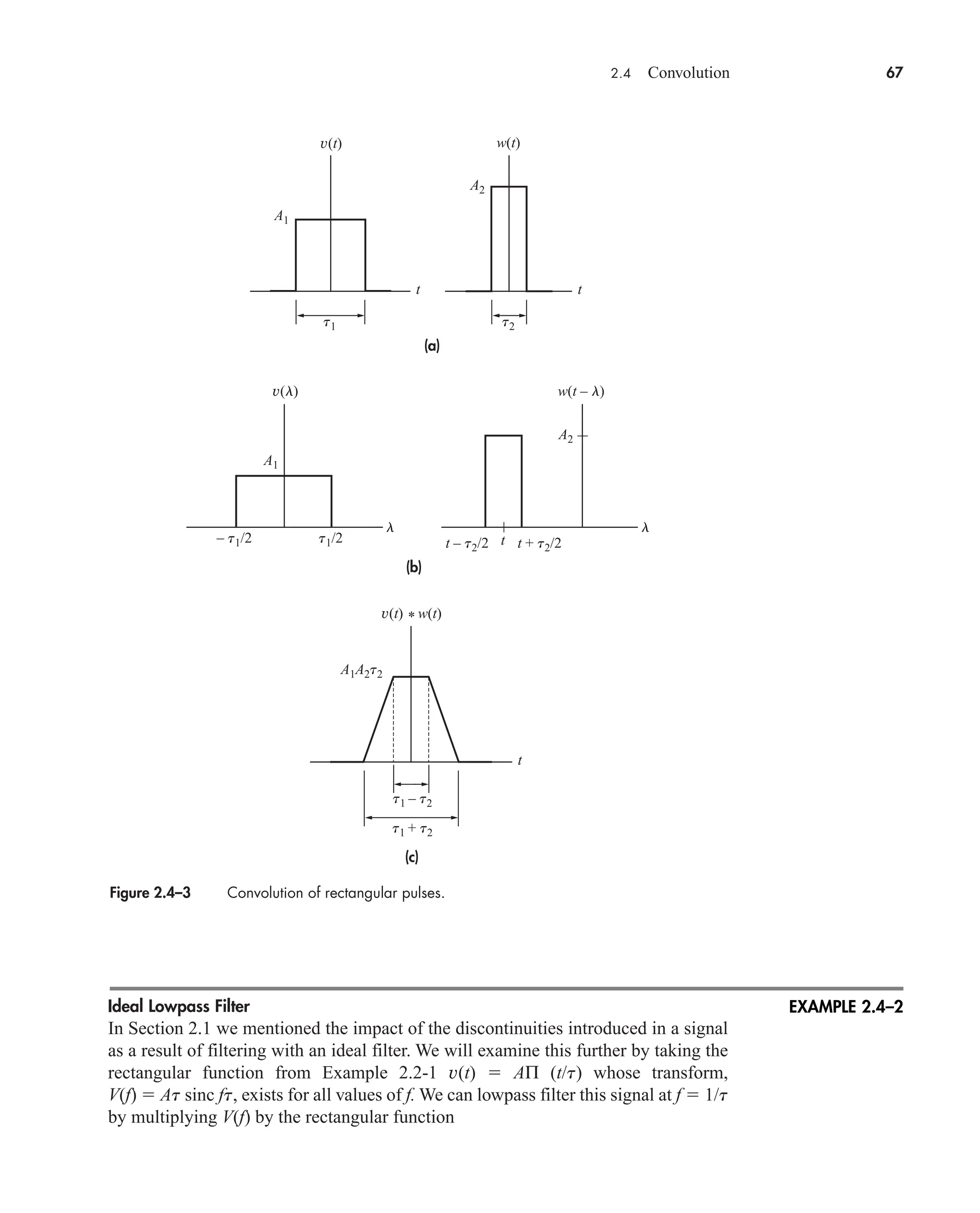

pX(x) probability density function of X

pXY(x) joint probability density function of X and Y

q number of quantum levels

r, rb signal rate, bit rate

s(t) switching function for sampling

s0(t), s1(t) inputs to multiplier of correlation detector

sgn(t) signum function

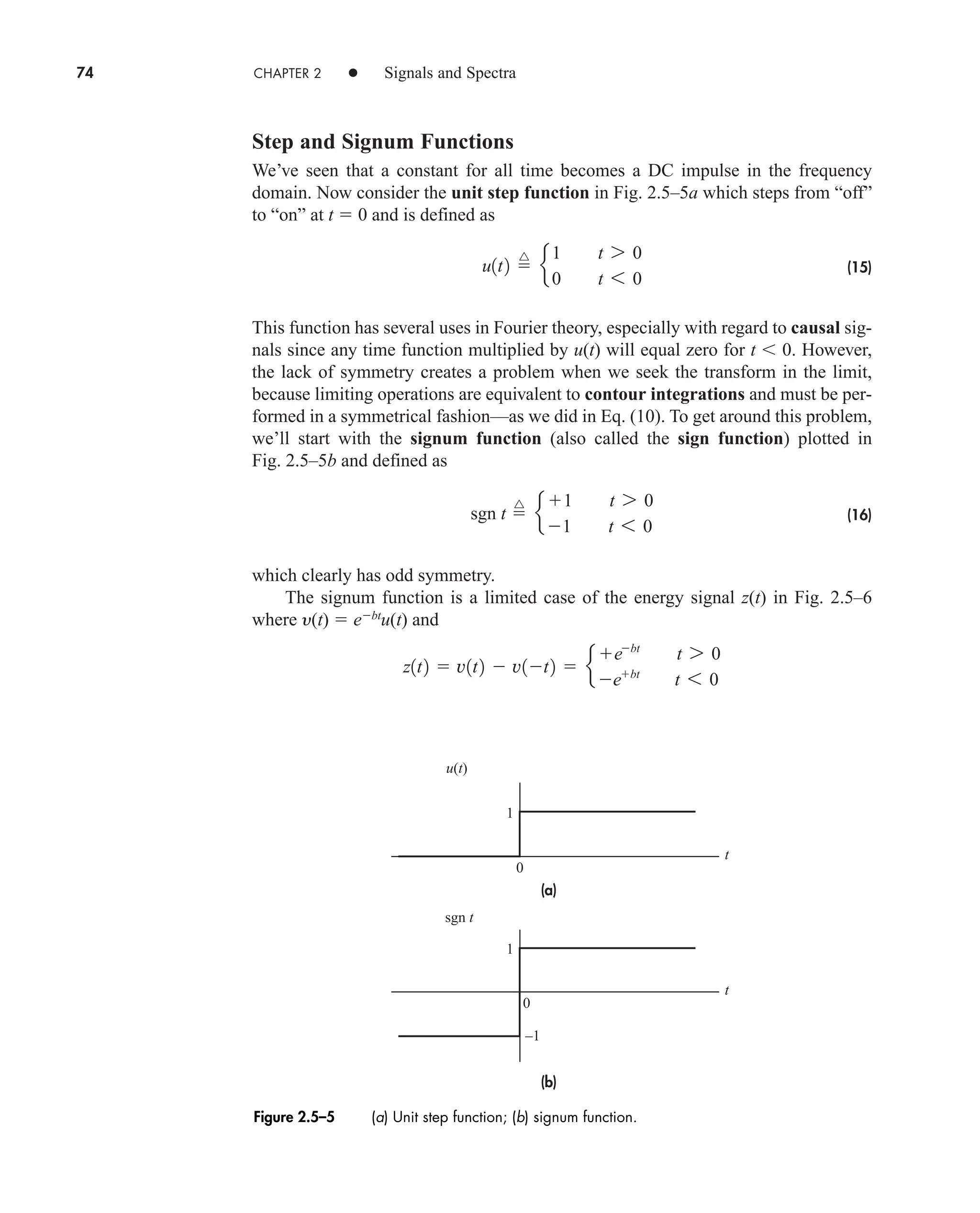

t time in seconds

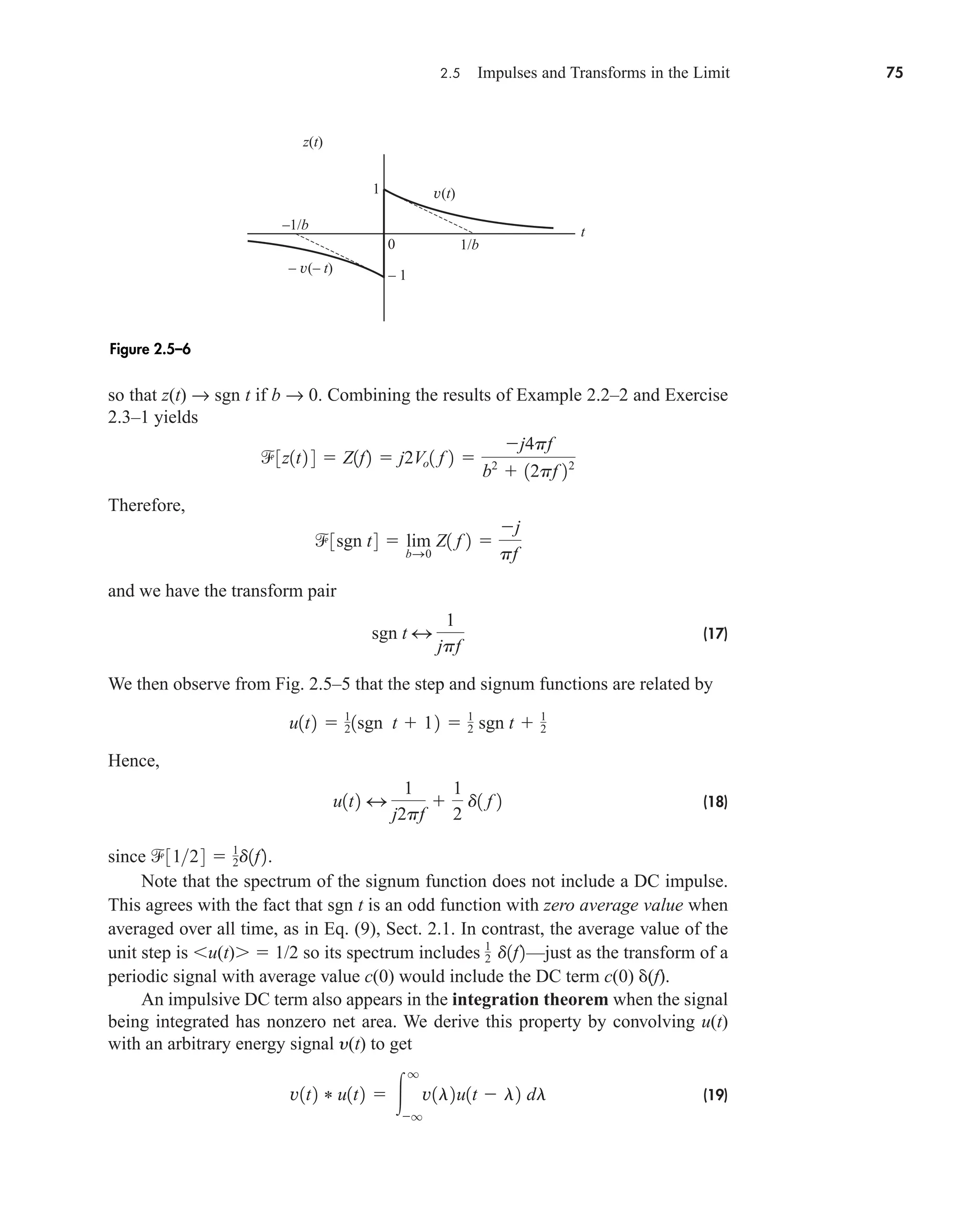

td time delay in seconds

tk kth instant of time

tr rise time in seconds

u(t) unit step function, or output from rake diversity combiner

v number of bits

v(t) input to a detector

vk (t) kth subcarrier function

v(t) average value of v(t)

vbp(t) time-domain expression of a bandpass signal

w*(t) complex conjugate of w(t)

Hilbert transform of x, or estimate of x

x(t), y(t) input and output time functions

x(t) message signal

x(k), x(kTs) sampled version of x(t)

X(n) discrete Fourier transform of x(k)

xb(t) modulated signal at a subcarrier frequency

xc(t) modulated signal

xq(k) quantized value for kth value of x

y(t) detector output

xk(t), yk(t) subchannel signal

yD(t) signal at destination

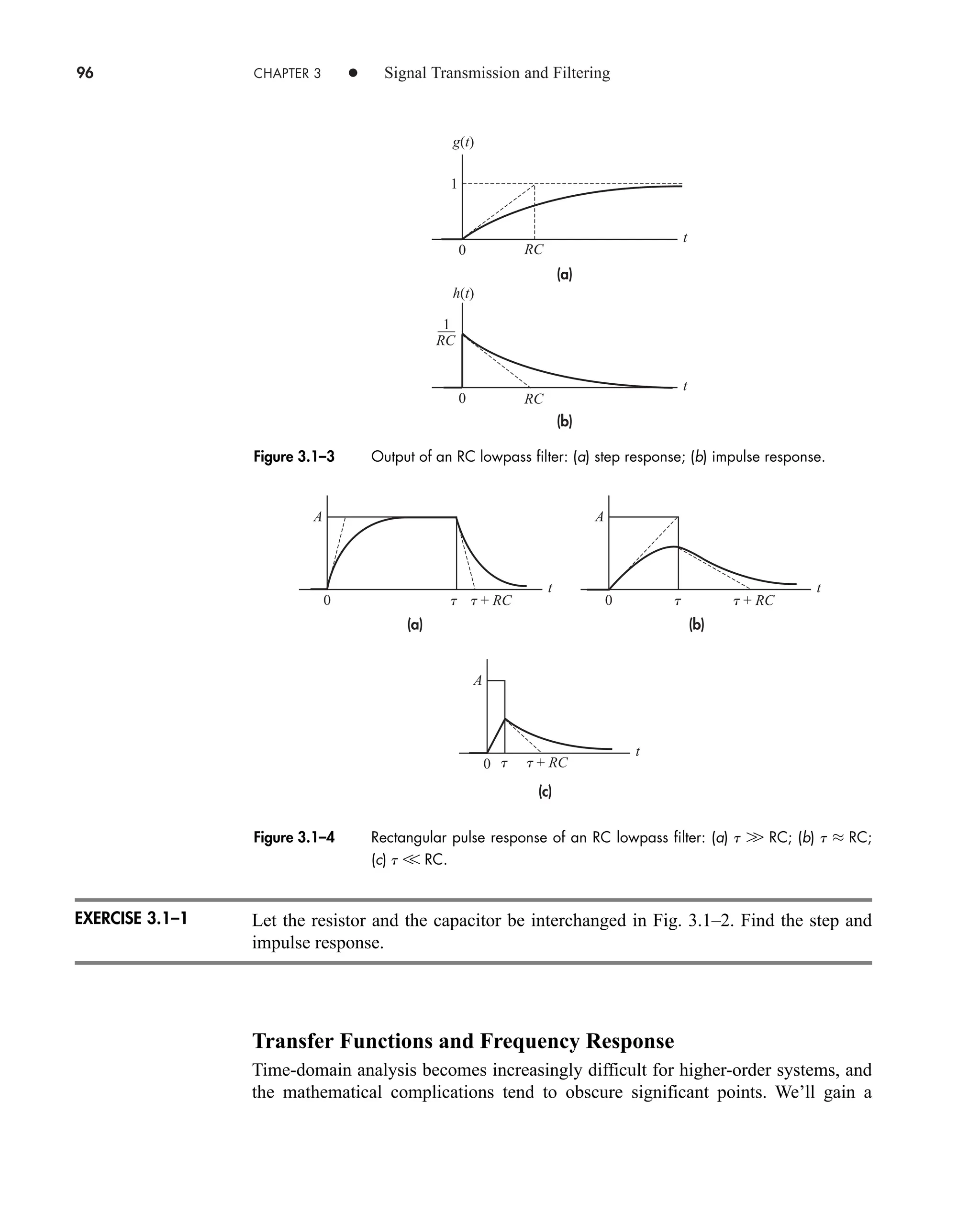

zm(t) output of matched filter or correlation detector

x̂

p

1t2

p

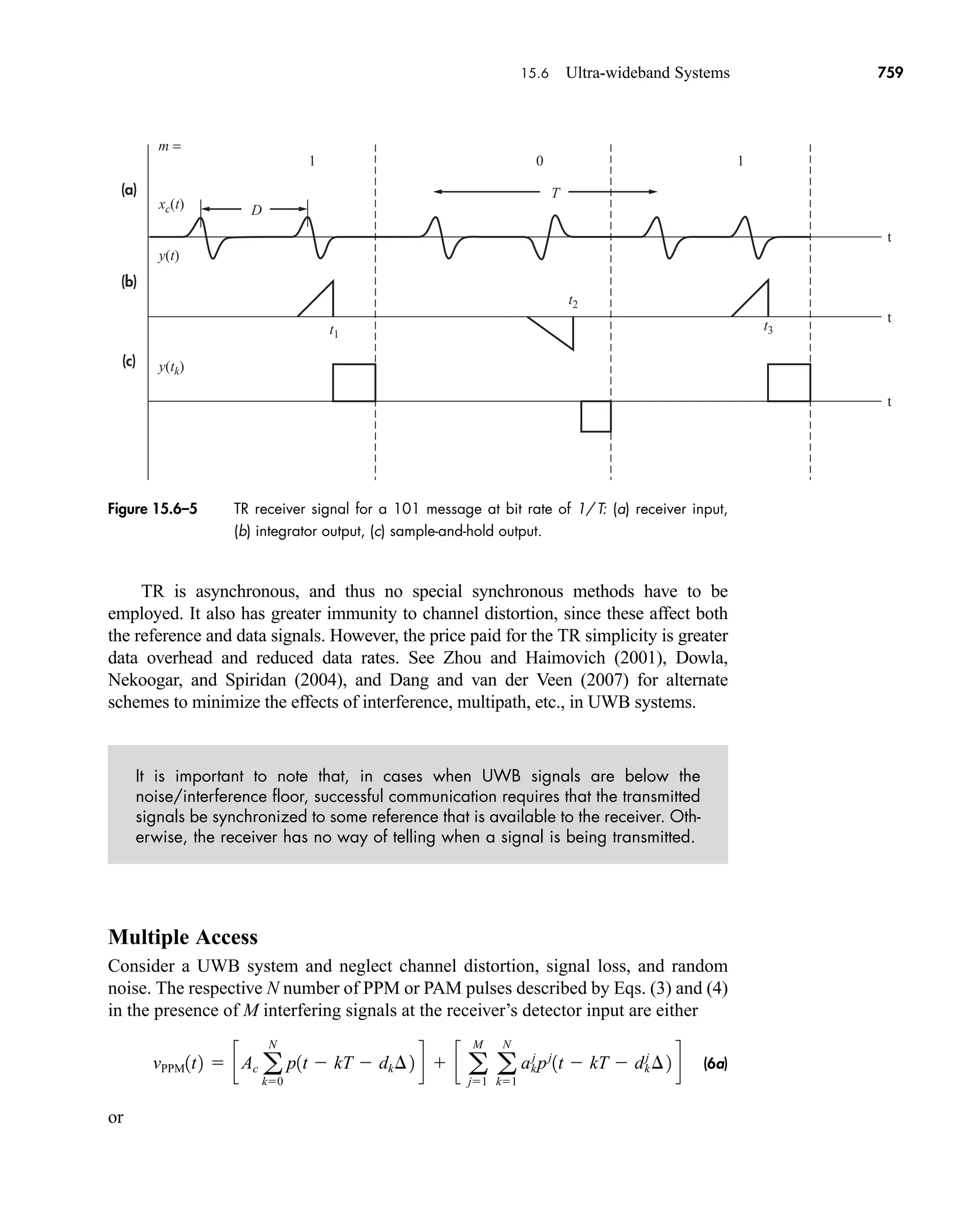

n

m̂

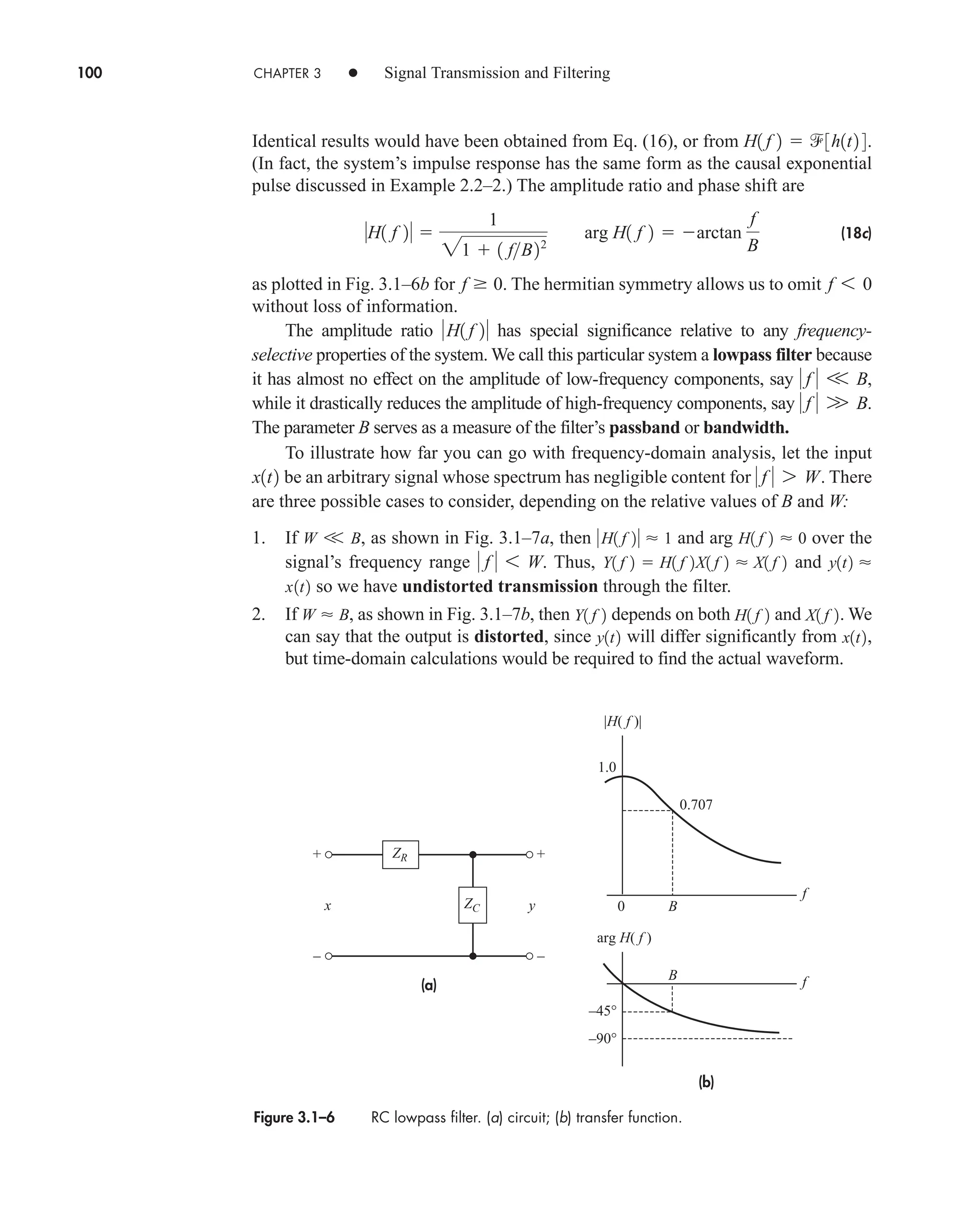

car80407_fm_i-xx.qxd 9/1/09 8:59 AM Page xix](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-21-2048.jpg)

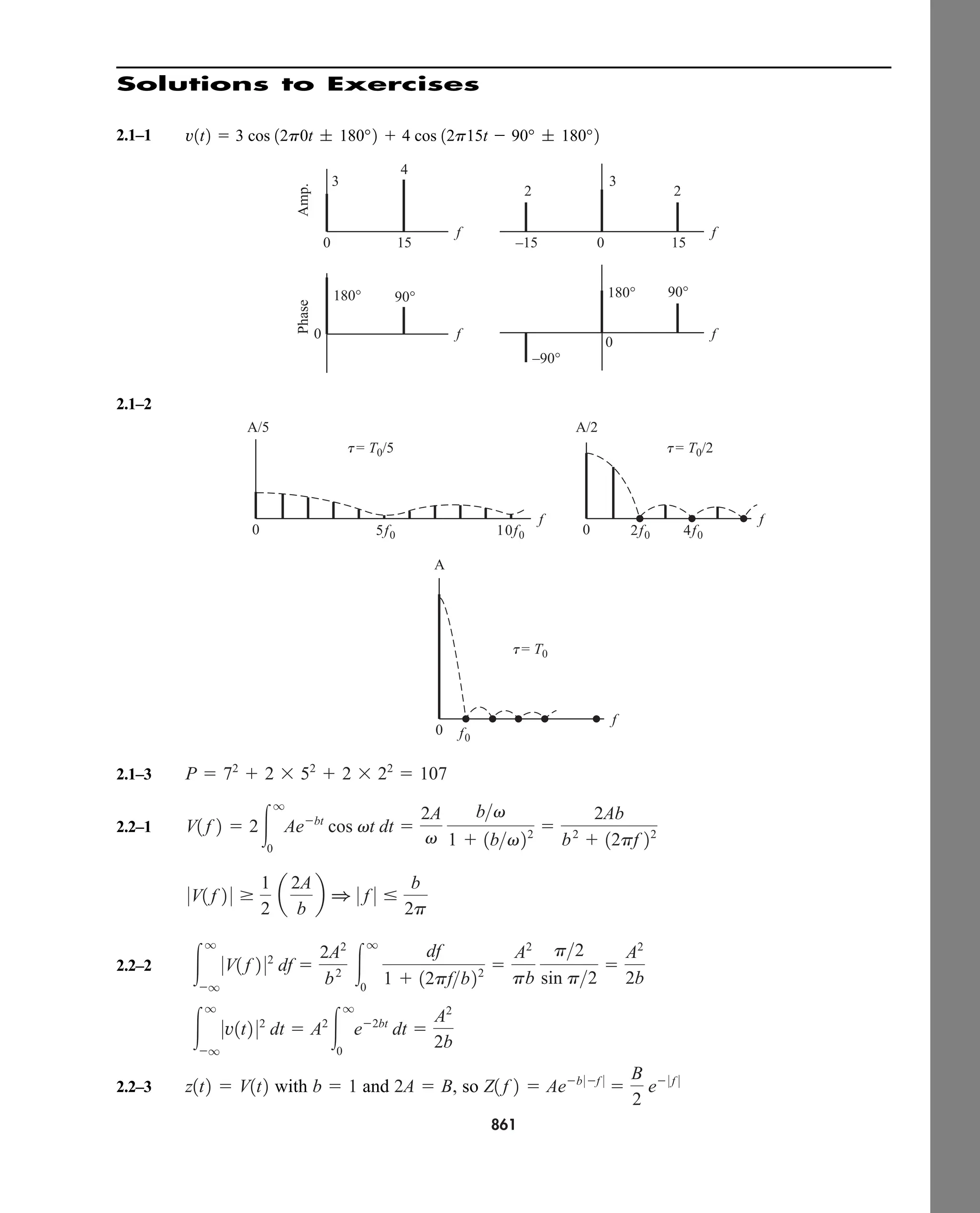

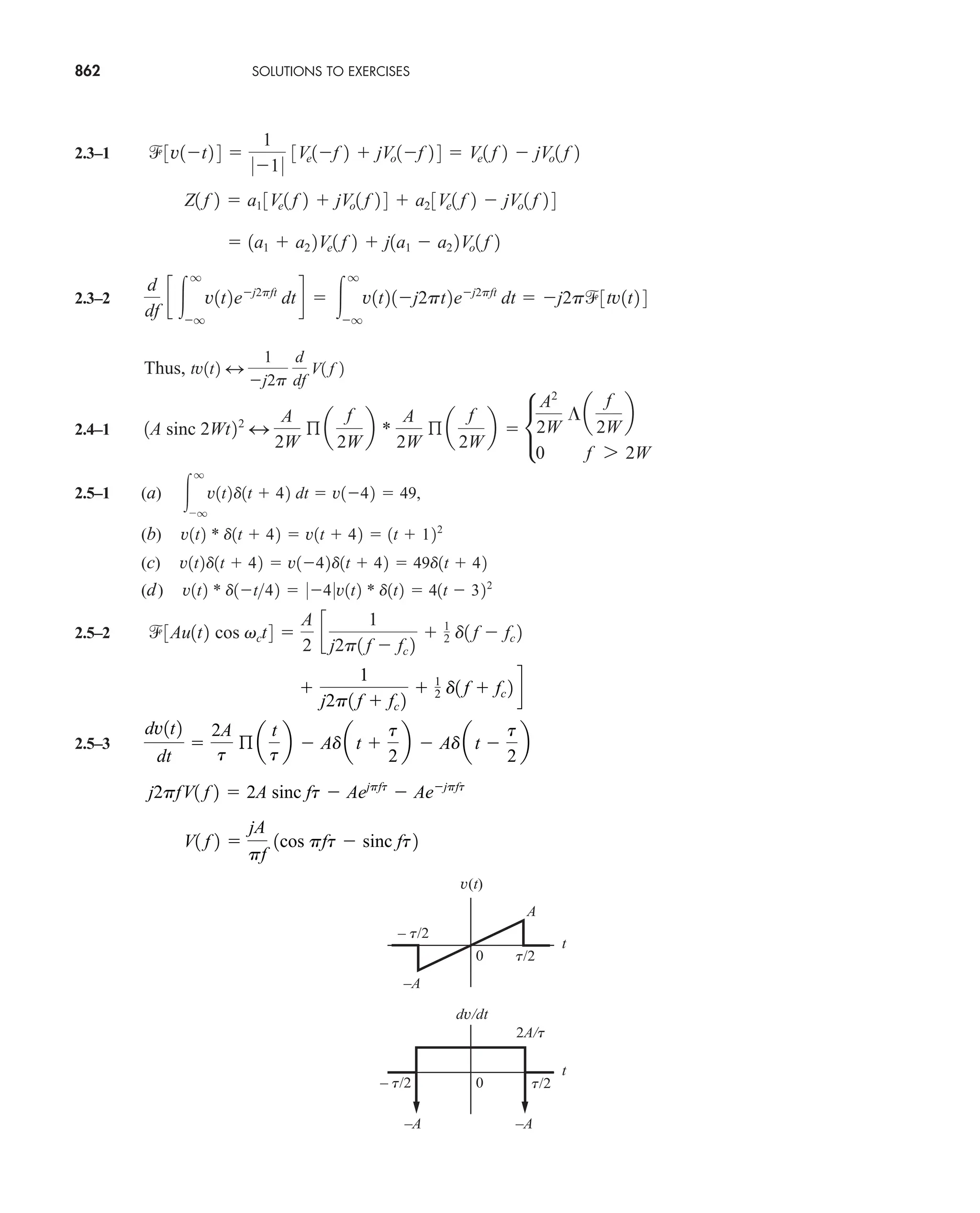

![36 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

Calculated values of c(0) may be checked by inspecting v(t)—a wise practice

when the integration gives an ambiguous result.

3. If v(t) is a real (noncomplex) function of time, then

(16a)

which follows from Eq. (14) with n replaced by n. Hence

(16b)

which means that the amplitude spectrum has even symmetry and the phase

spectrum has odd symmetry.

When dealing with real signals, the property in Eq. (16) allows us to regroup the

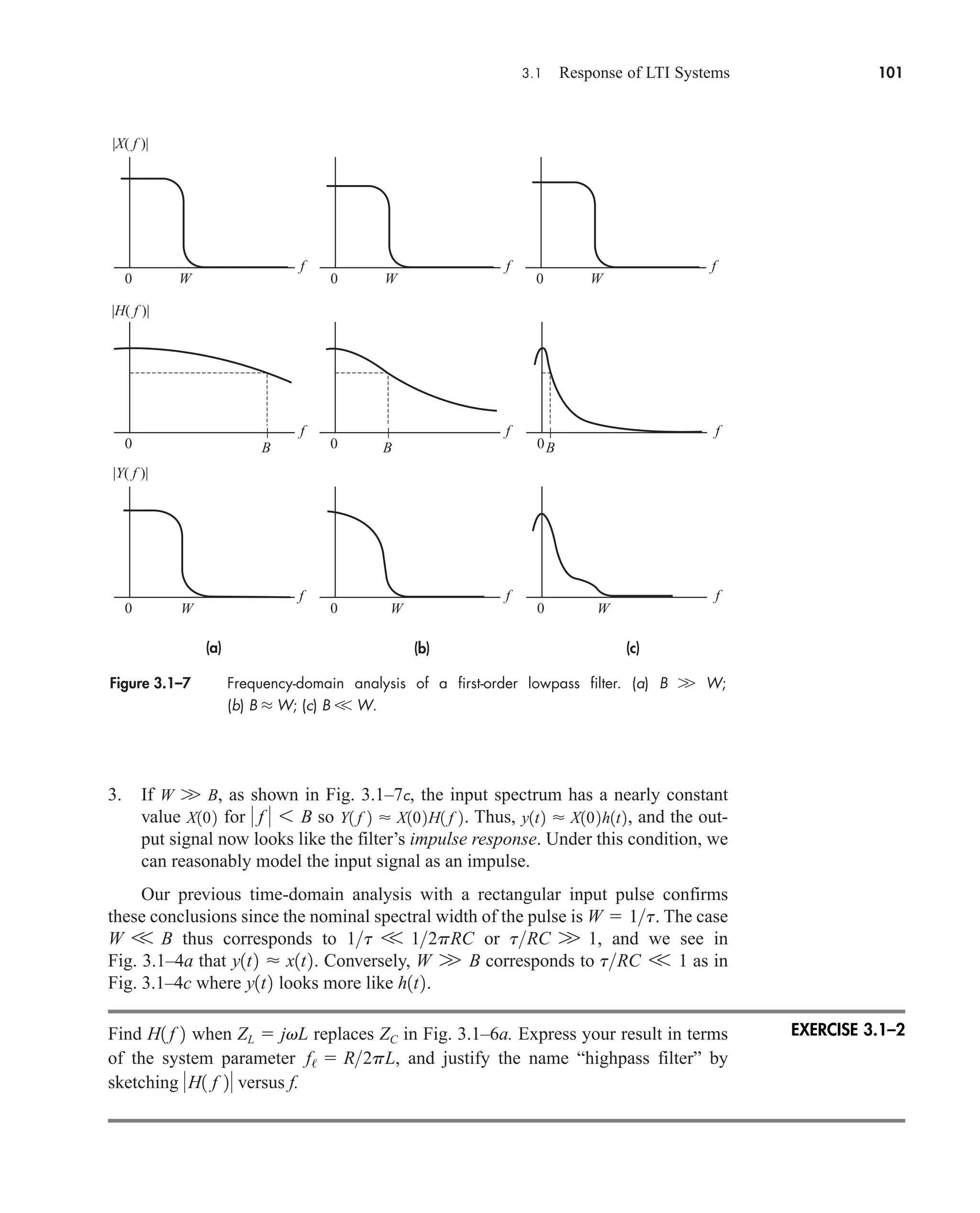

exponential series into complex-conjugate pairs, except for c0. Equation (13) then

becomes

(17a)

or

(17b)

an Re[cn]

and bn Im[cn]. Re[ ] and Im[ ] being the real and imaginary operators respectively.

Equation 17a is the trigonometric Fourier Series and suggests a one-sided

spectrum. Most of the time, however, we’ll use the exponential series and two-sided

spectra.

The sinusoidal terms in Eq. (17) represent a set of orthogonal basis functions.

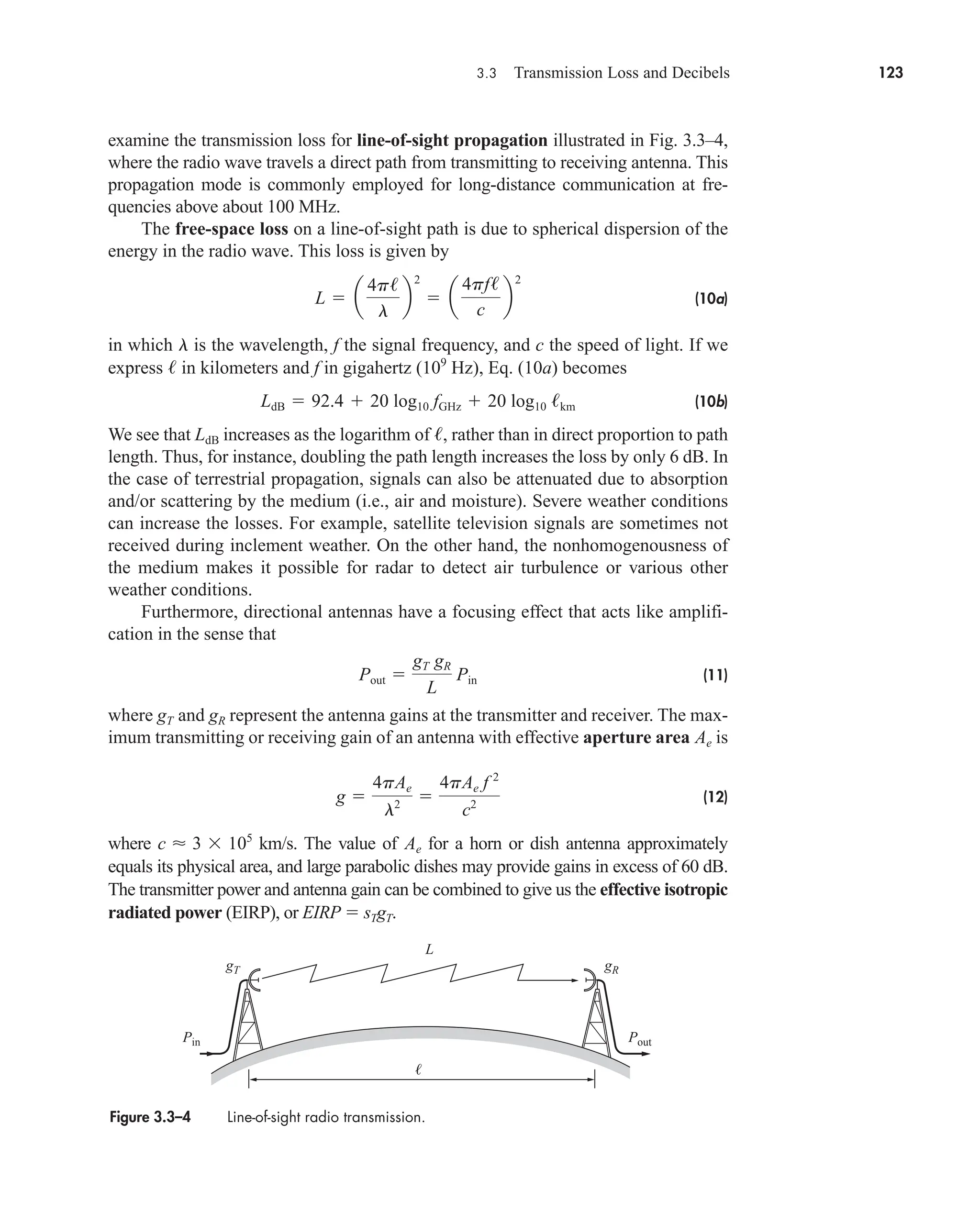

Functions vn(t) and vm(t) are orthogonal over an interval from t1 to t2 if

Later we will see in Sect. 7.2 (QAM) and 14.5 that a set of users can share a

channel without interfering with each other by using orthogonal carrier signals.

One final comment should be made before taking up an example. The integra-

tion for cn often involves a phasor average in the form

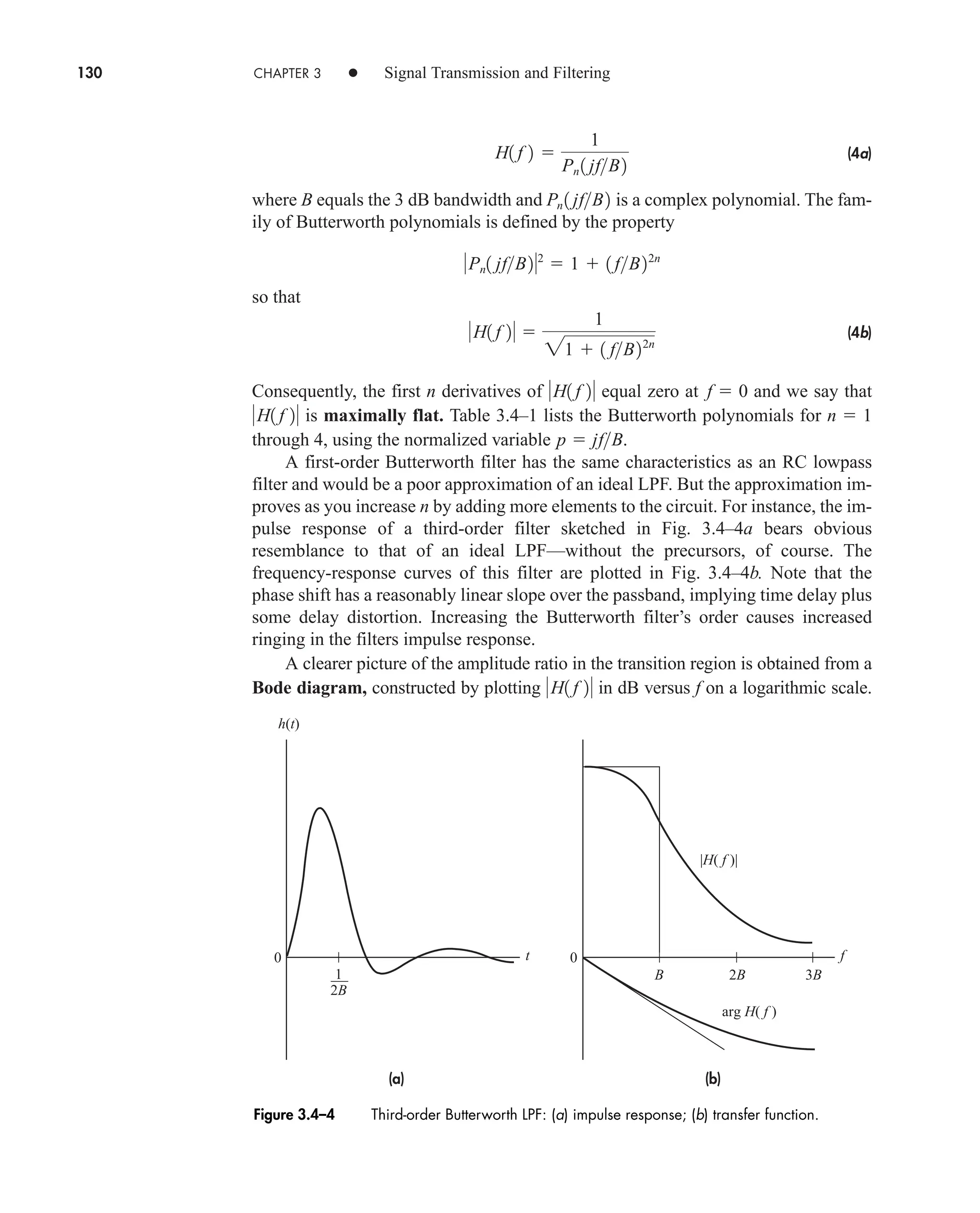

(18)

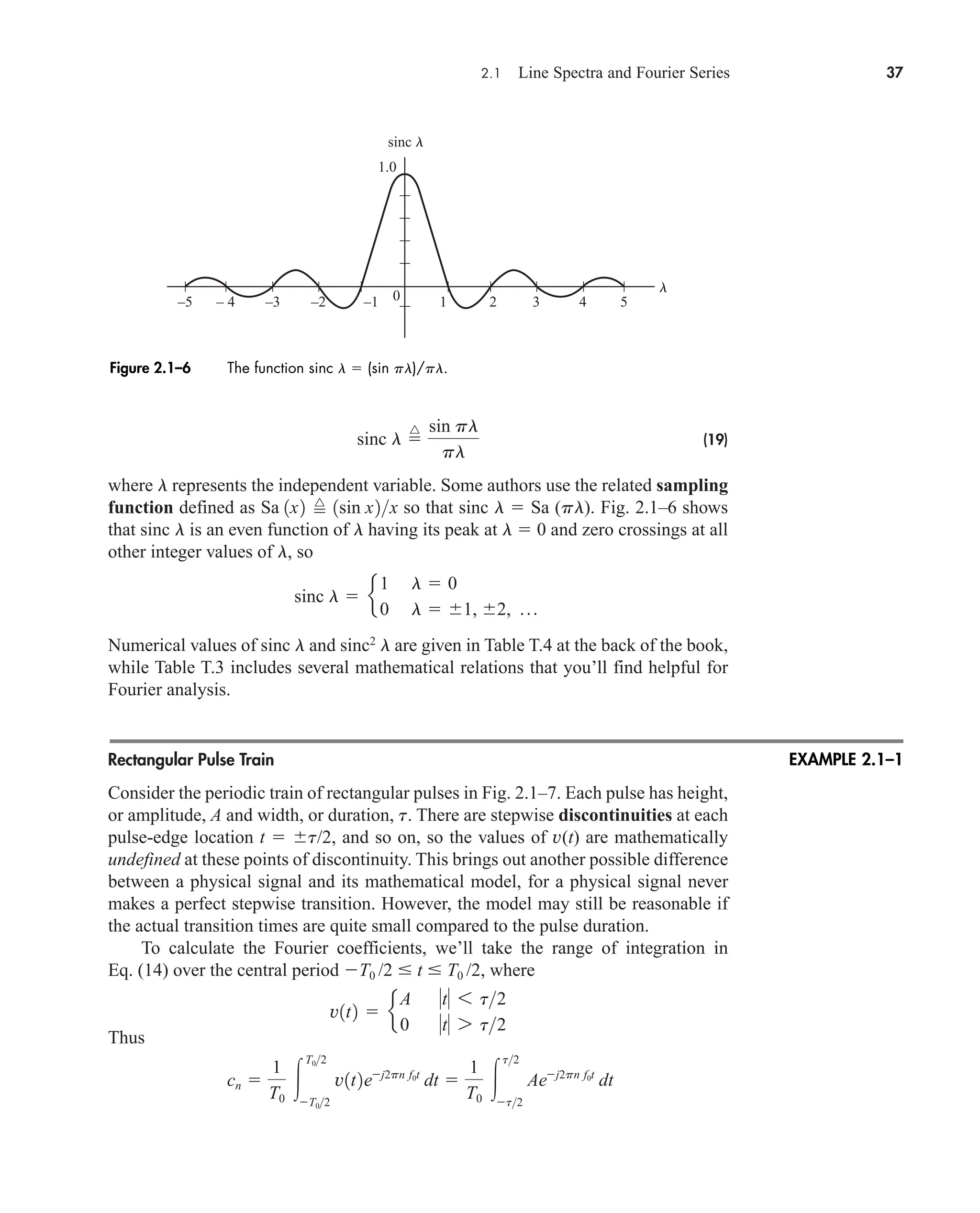

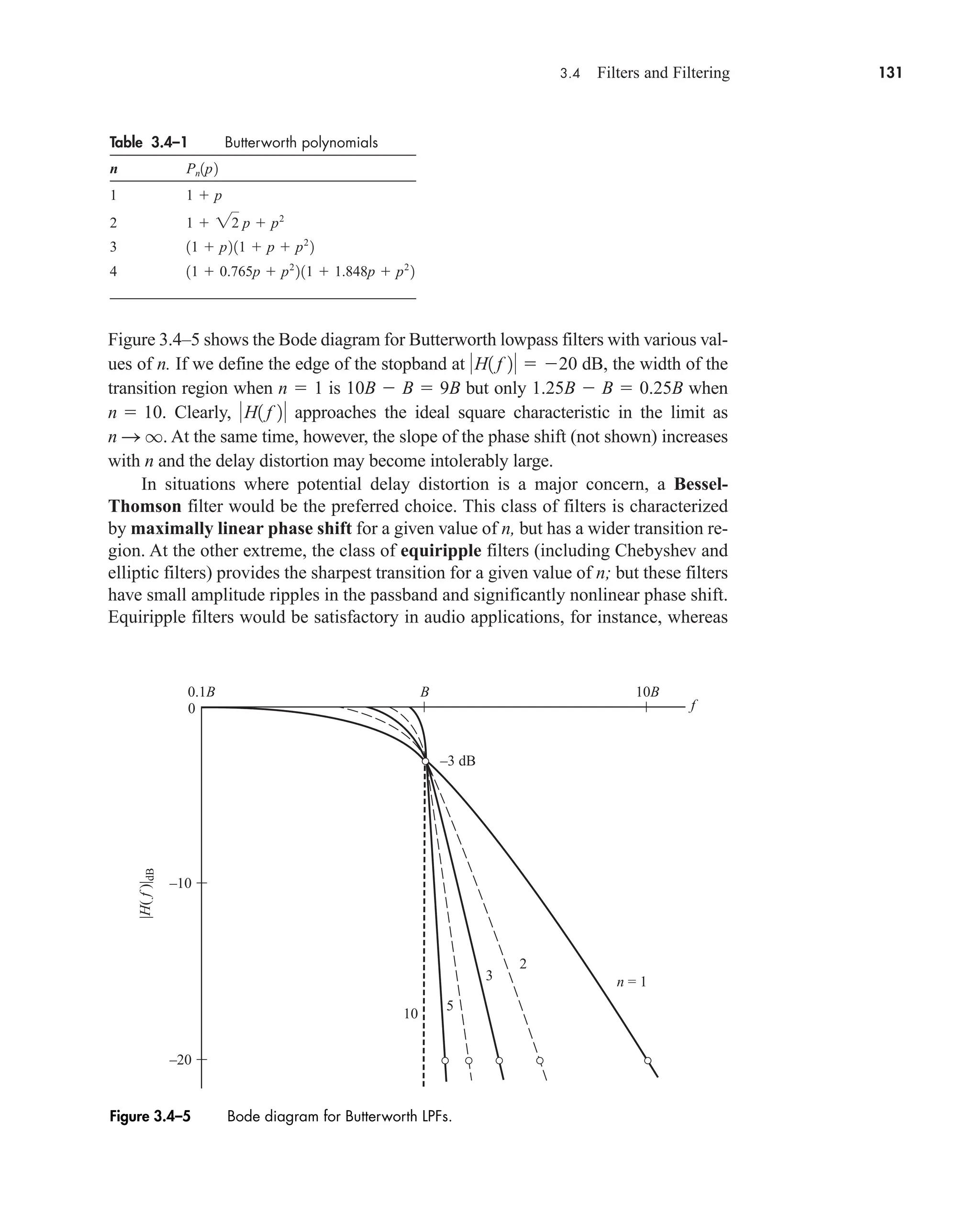

Since this expression occurs time and again in spectral analysis, we’ll now introduce

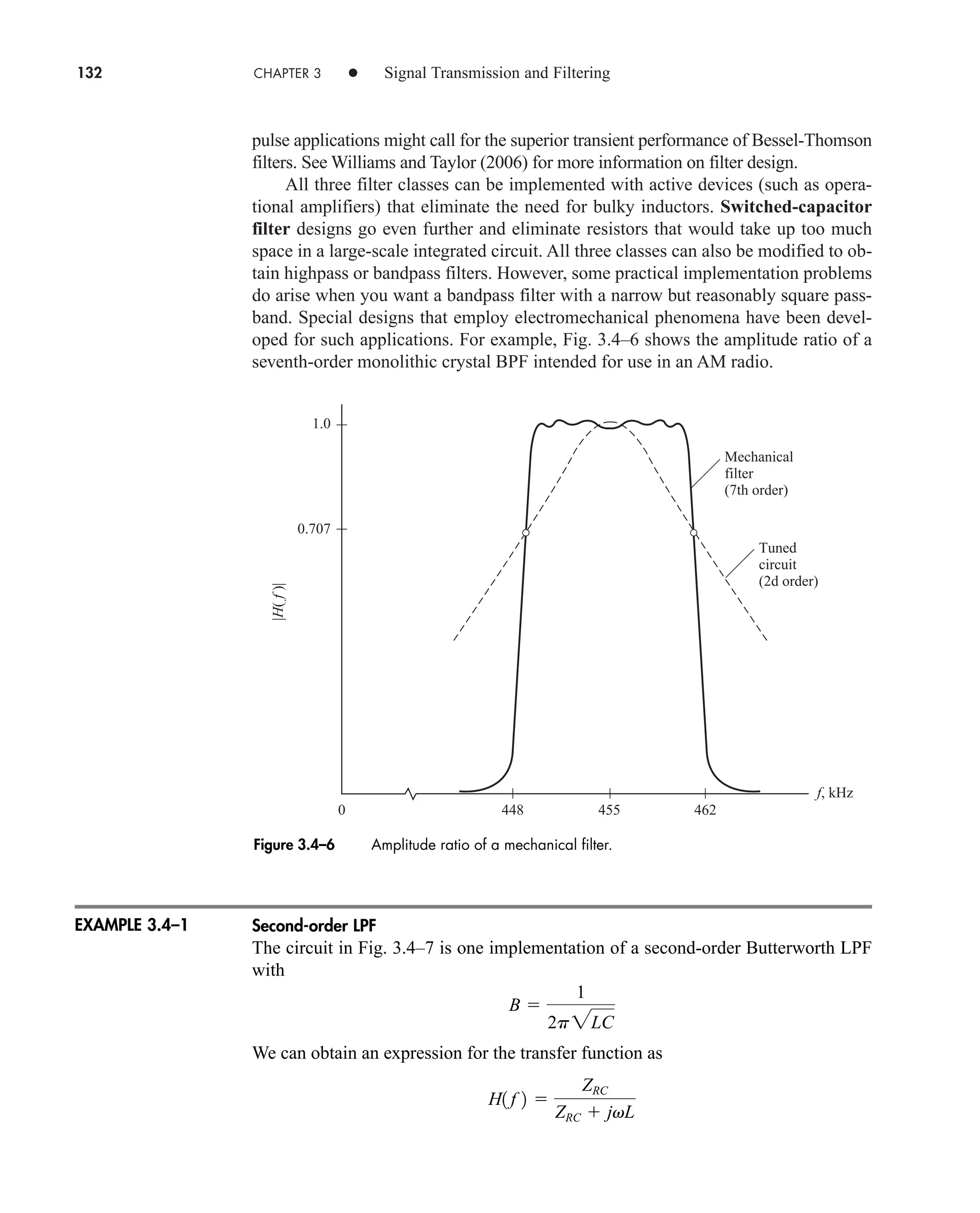

the sinc function defined by

1

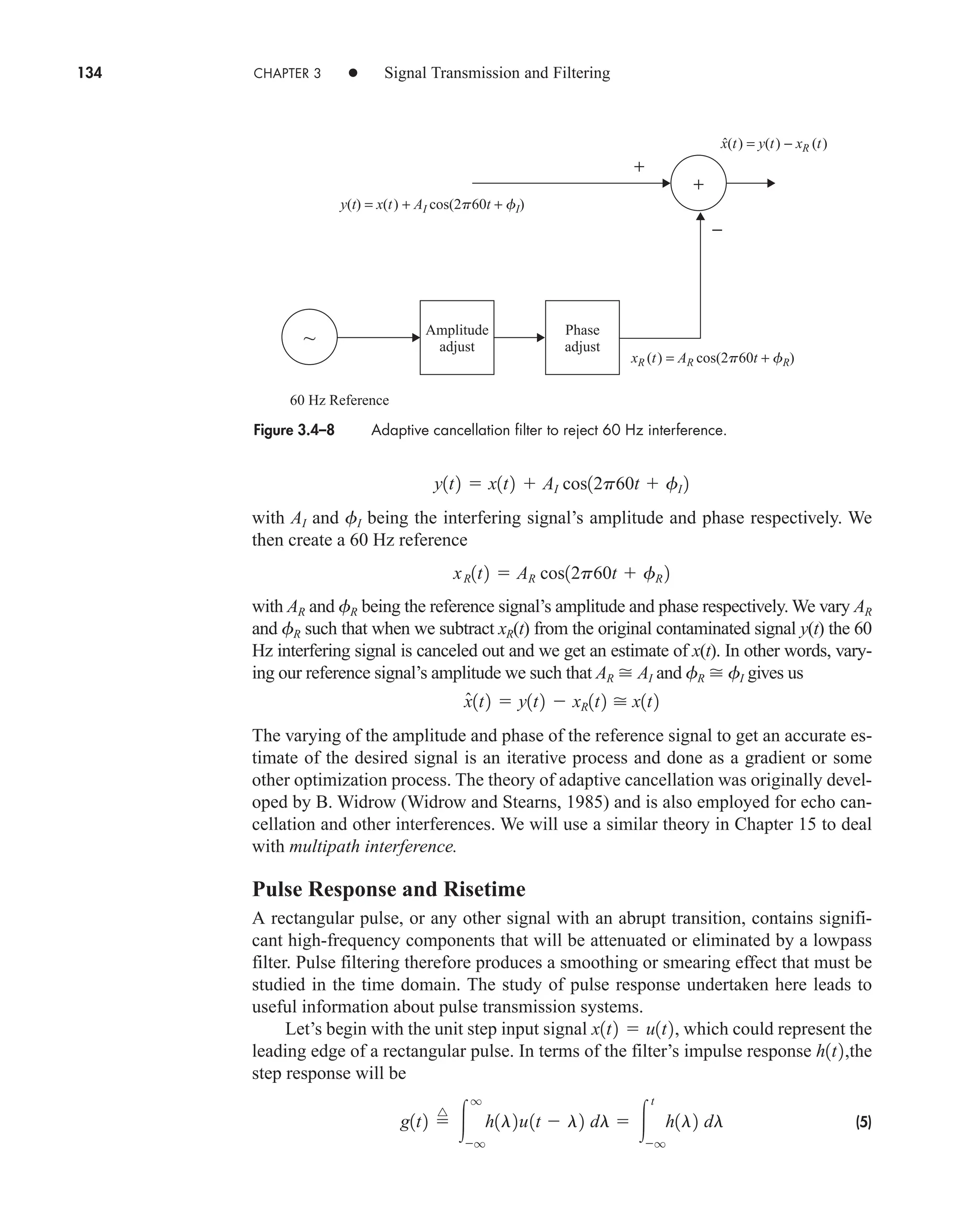

pf T

sin pf T

1

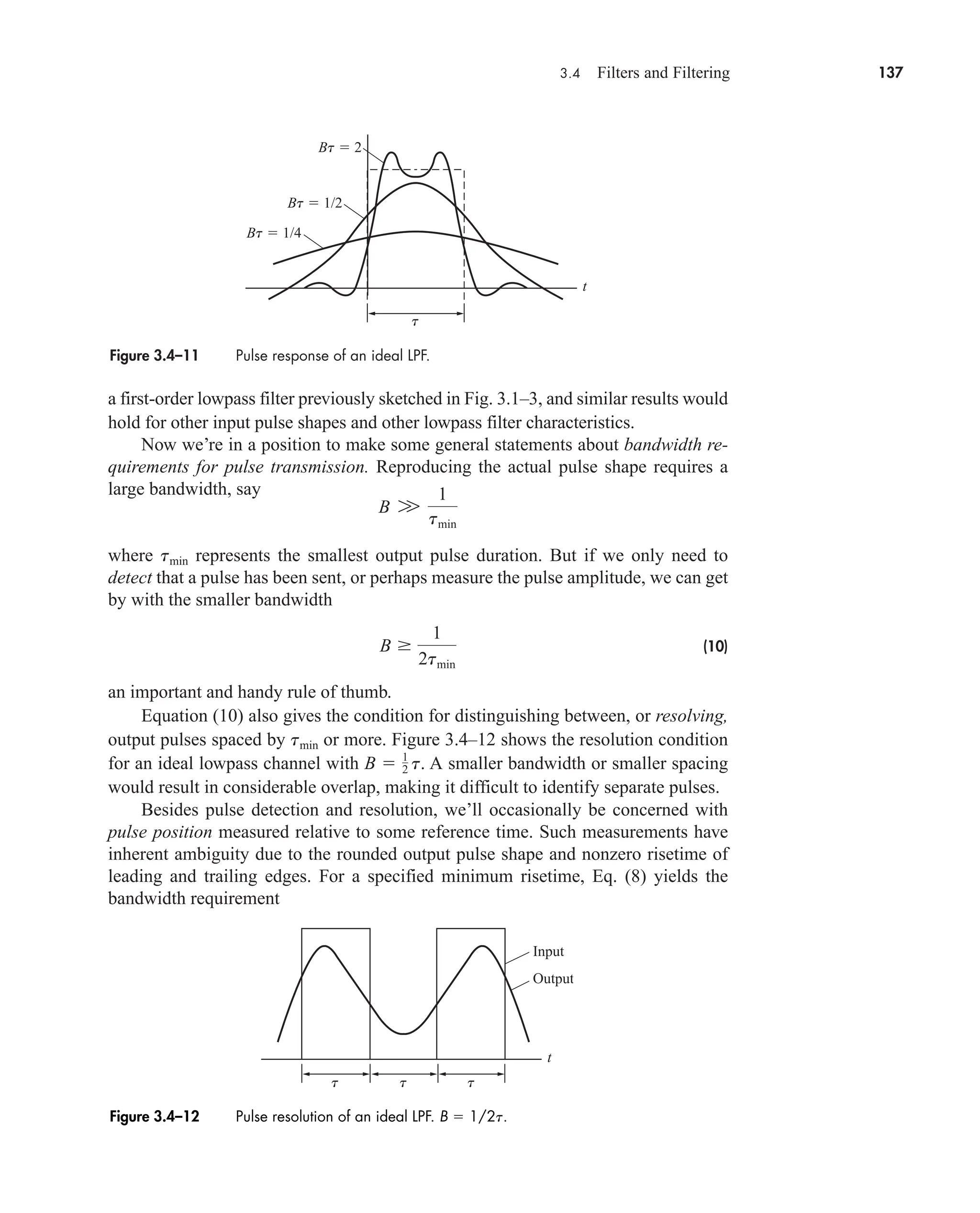

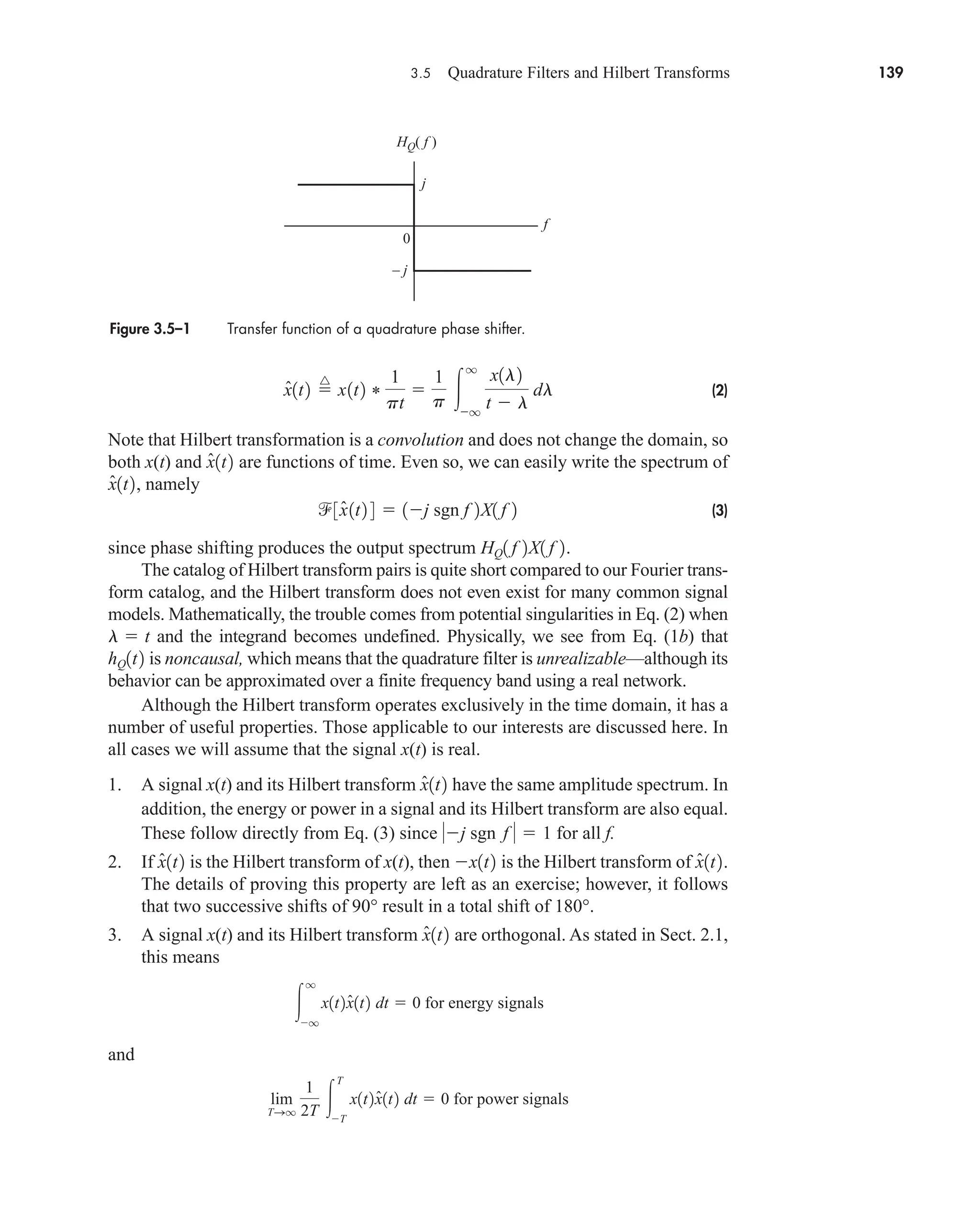

T

T2

T2

ej2pft

dt

1

j2pf T

1ejpf T

ejpf T

2

t2

t1

vn1t2vm1t2dt e

0 n m

K n m

with K a constant.

v1t2 c0 a

q

n1

3an cos 2pnf0t bn sin 2pf0t4

v1t2 c0 a

q

n1

2cn cos12pnf0t arg cn 2

c1nf0 2 c1nf0 2 arg c1nf0 2 arg c1nf0 2

cn c*

n cn ej arg cn

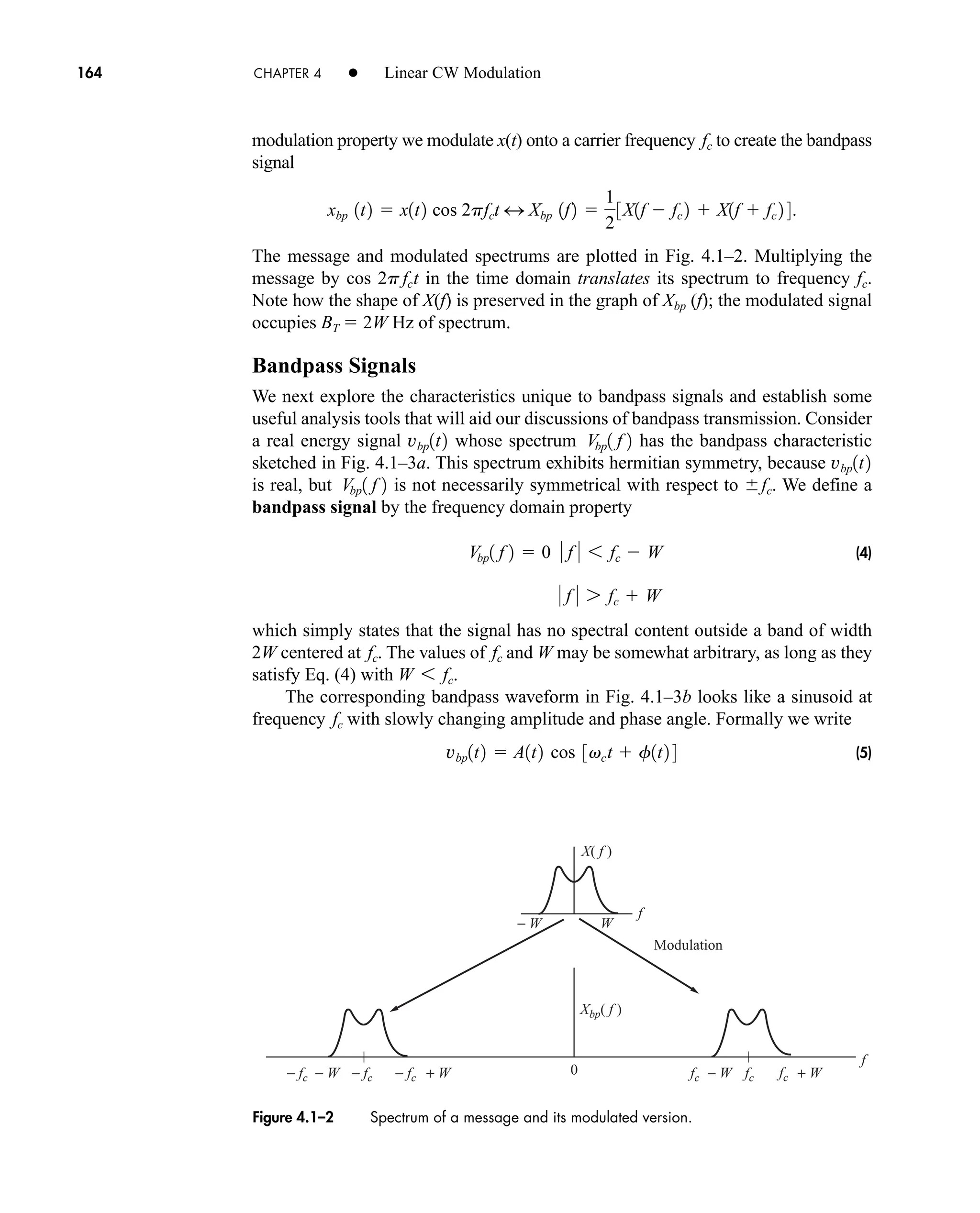

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:03 PM Page 36](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-58-2048.jpg)

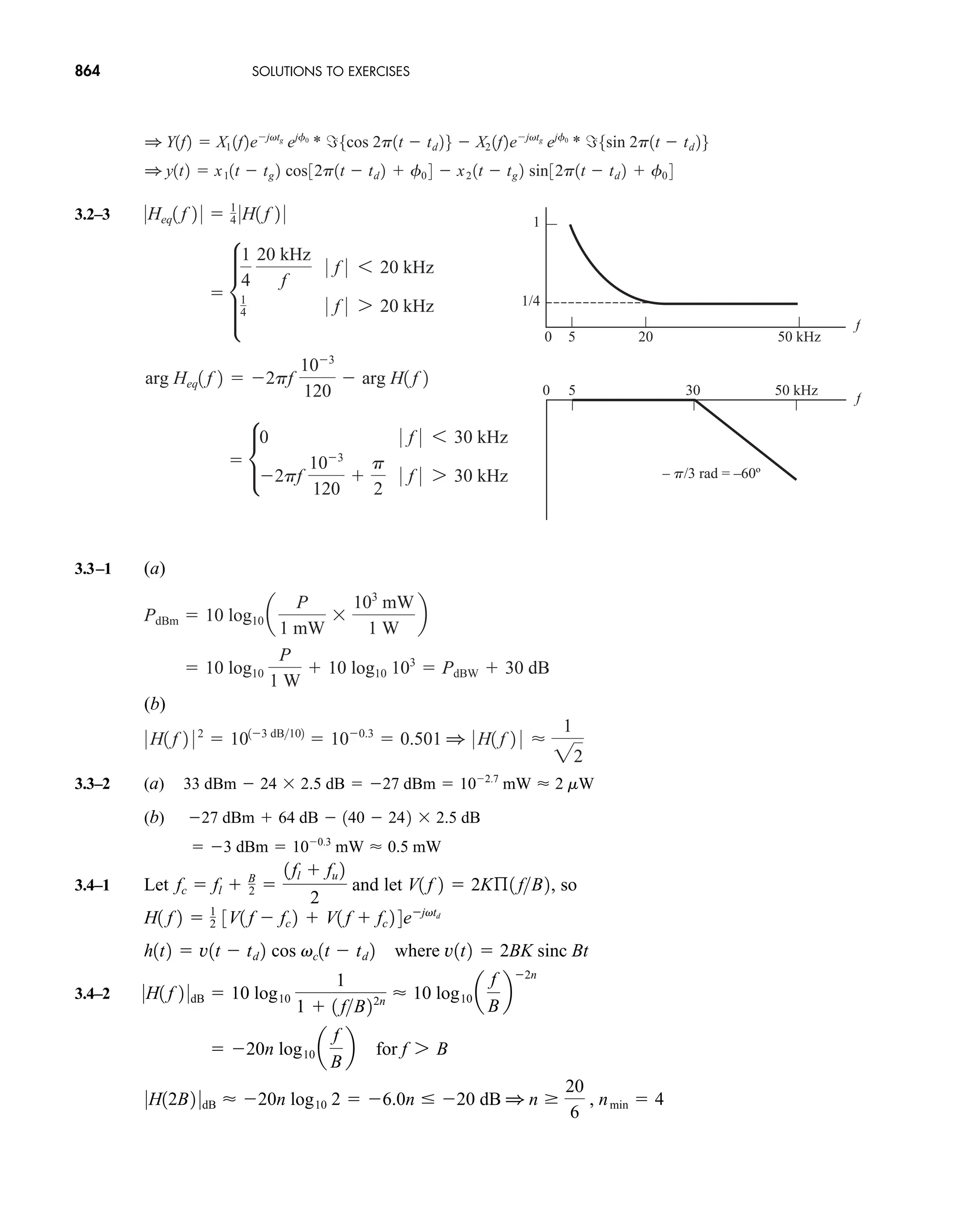

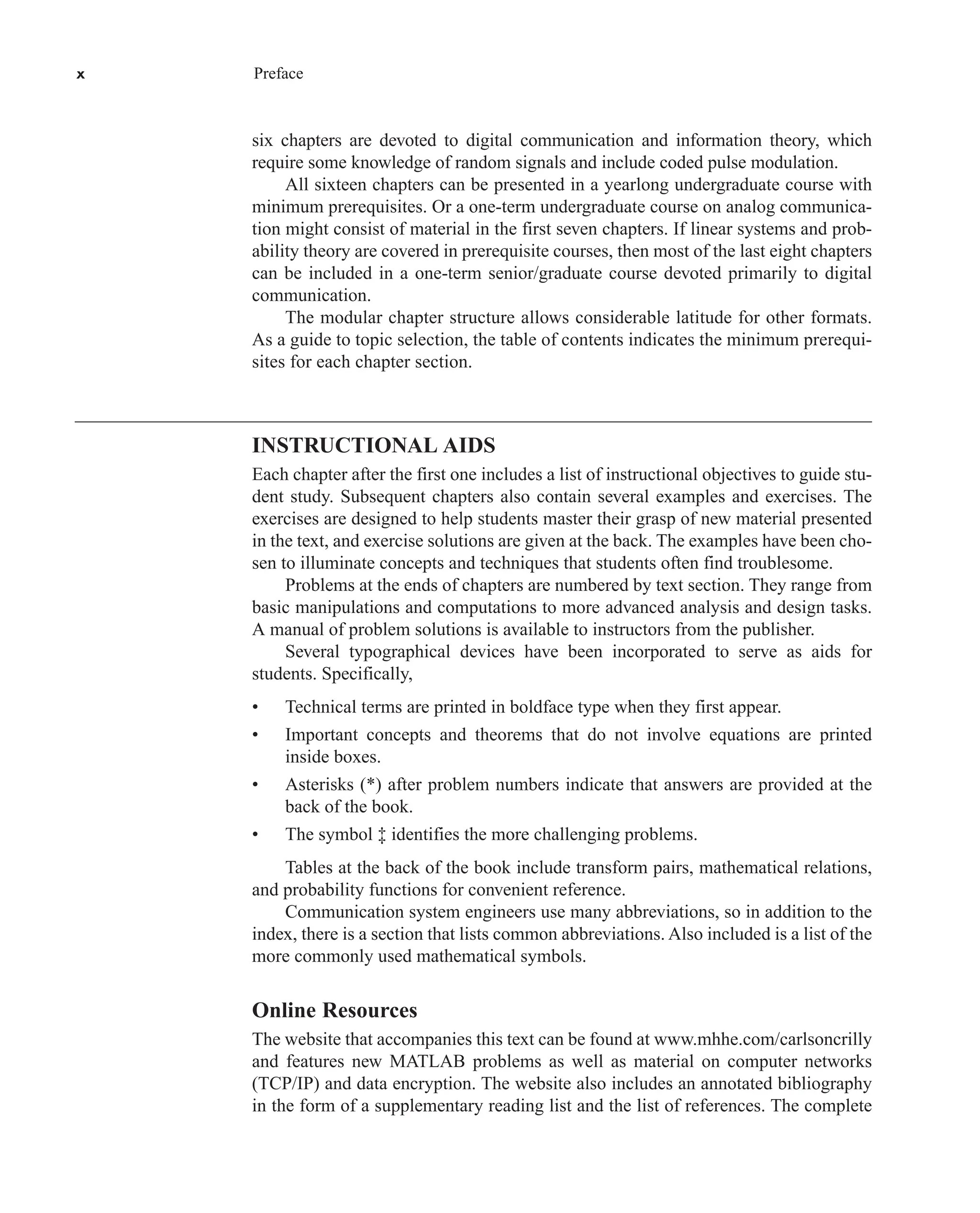

![38 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

Multiplying and dividing by t finally gives

(20)

which follows from Eq. (19) with l nf0 t.

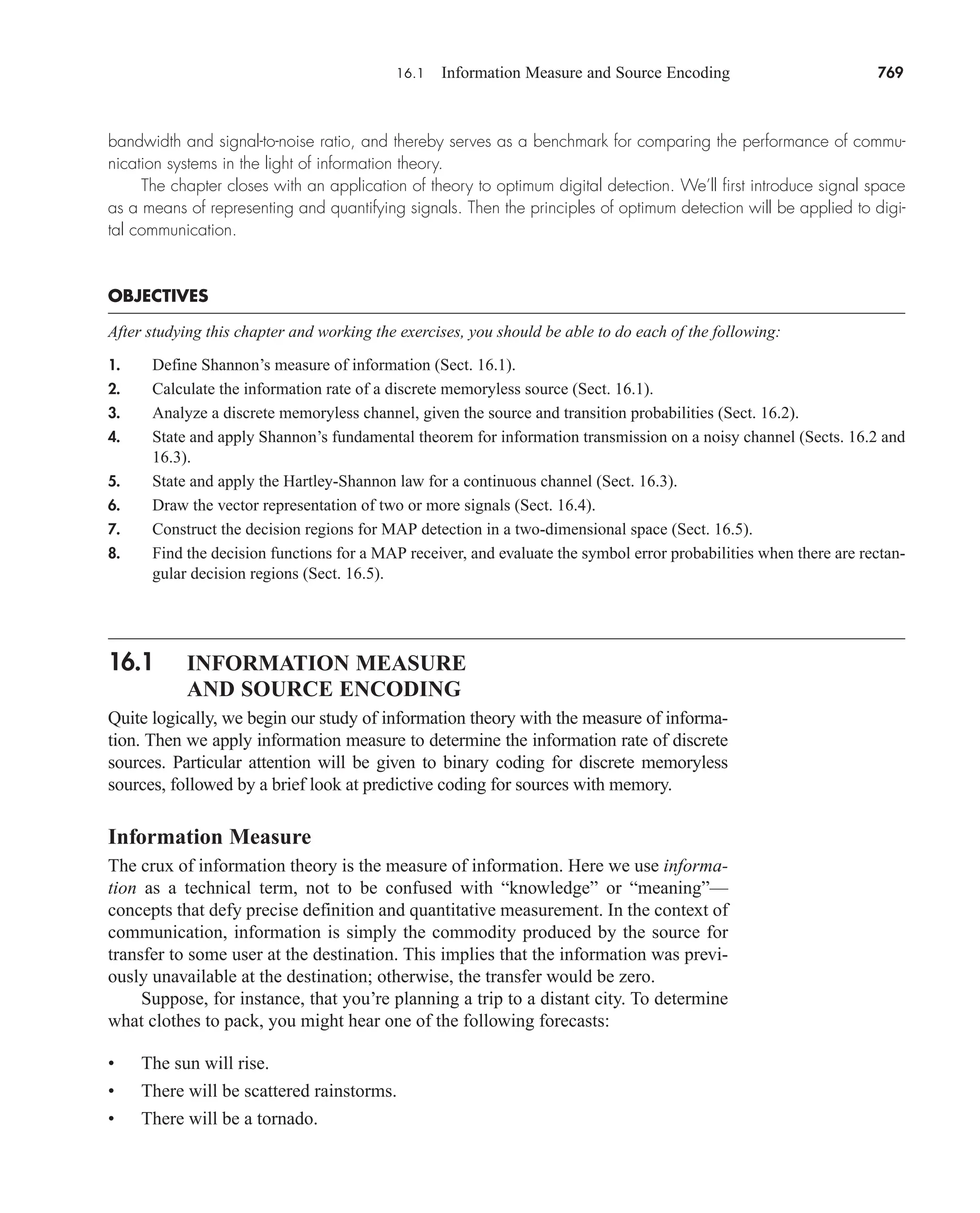

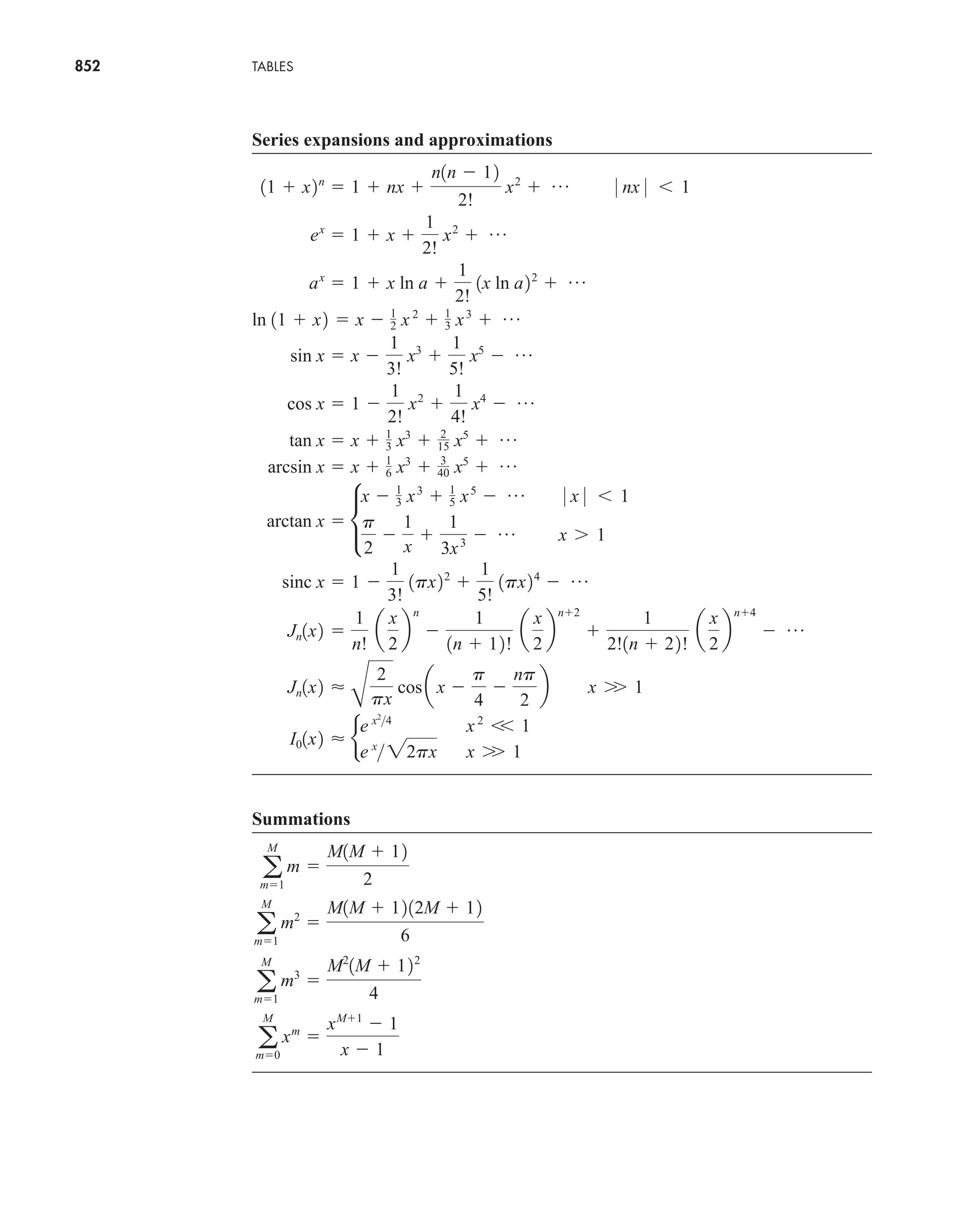

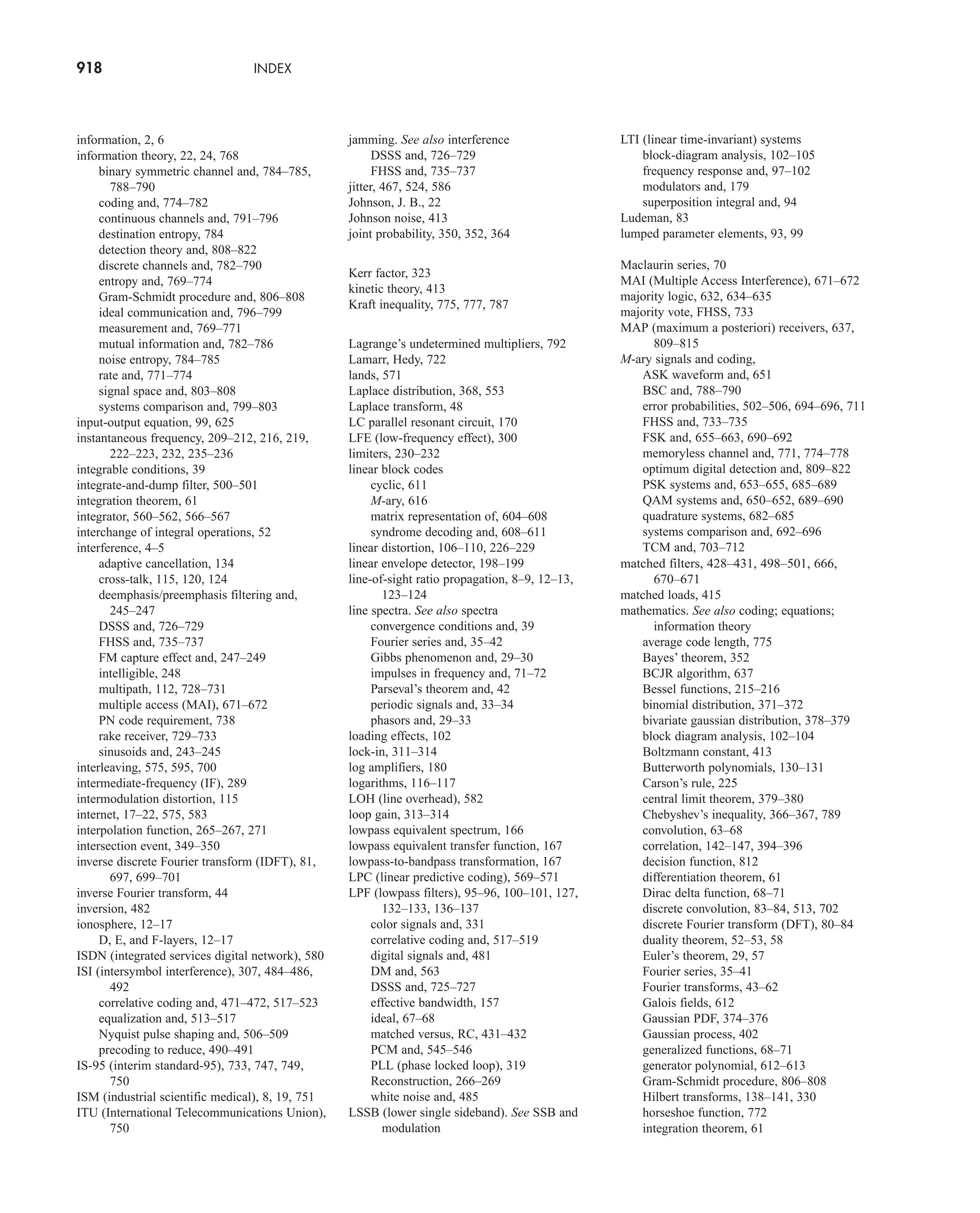

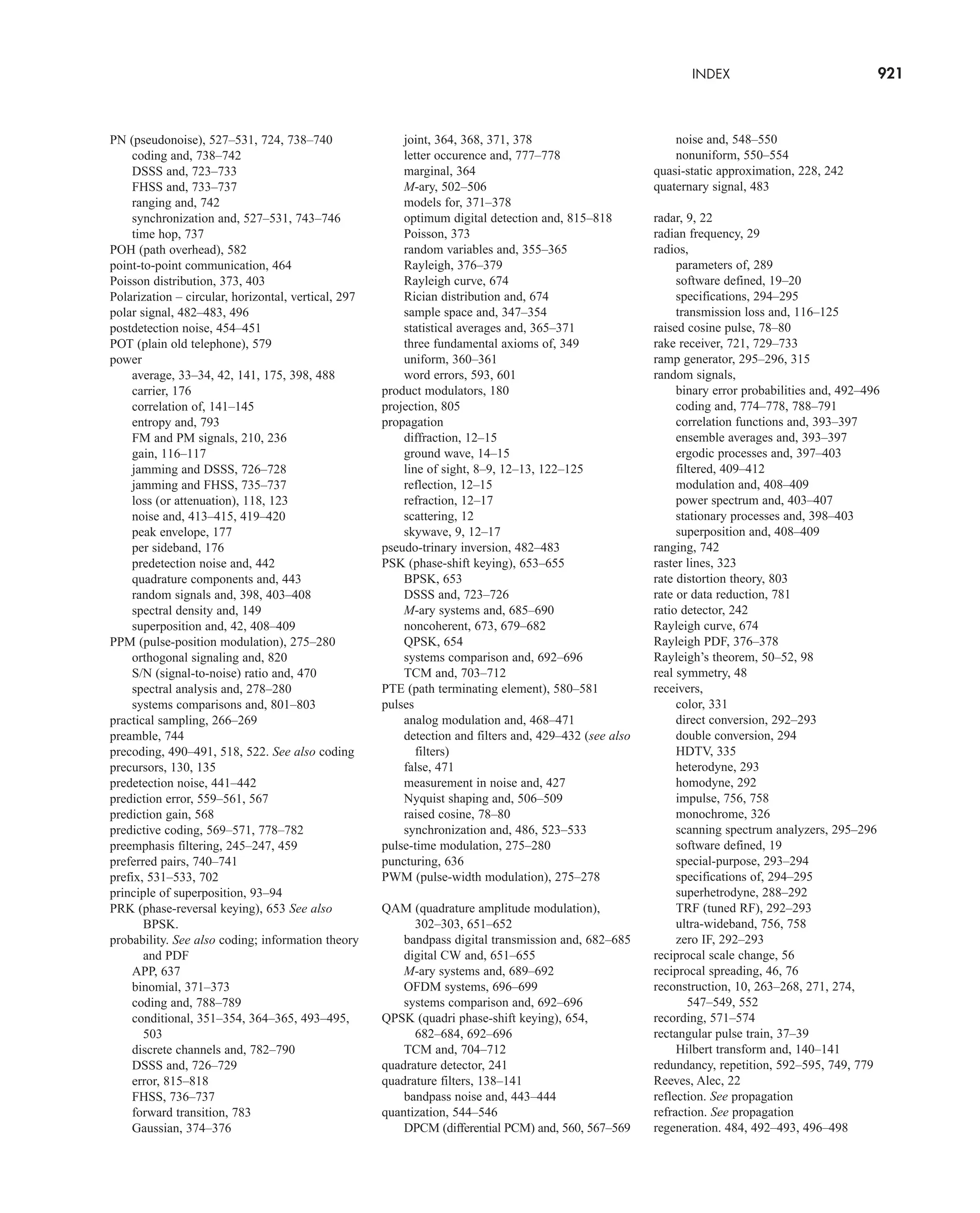

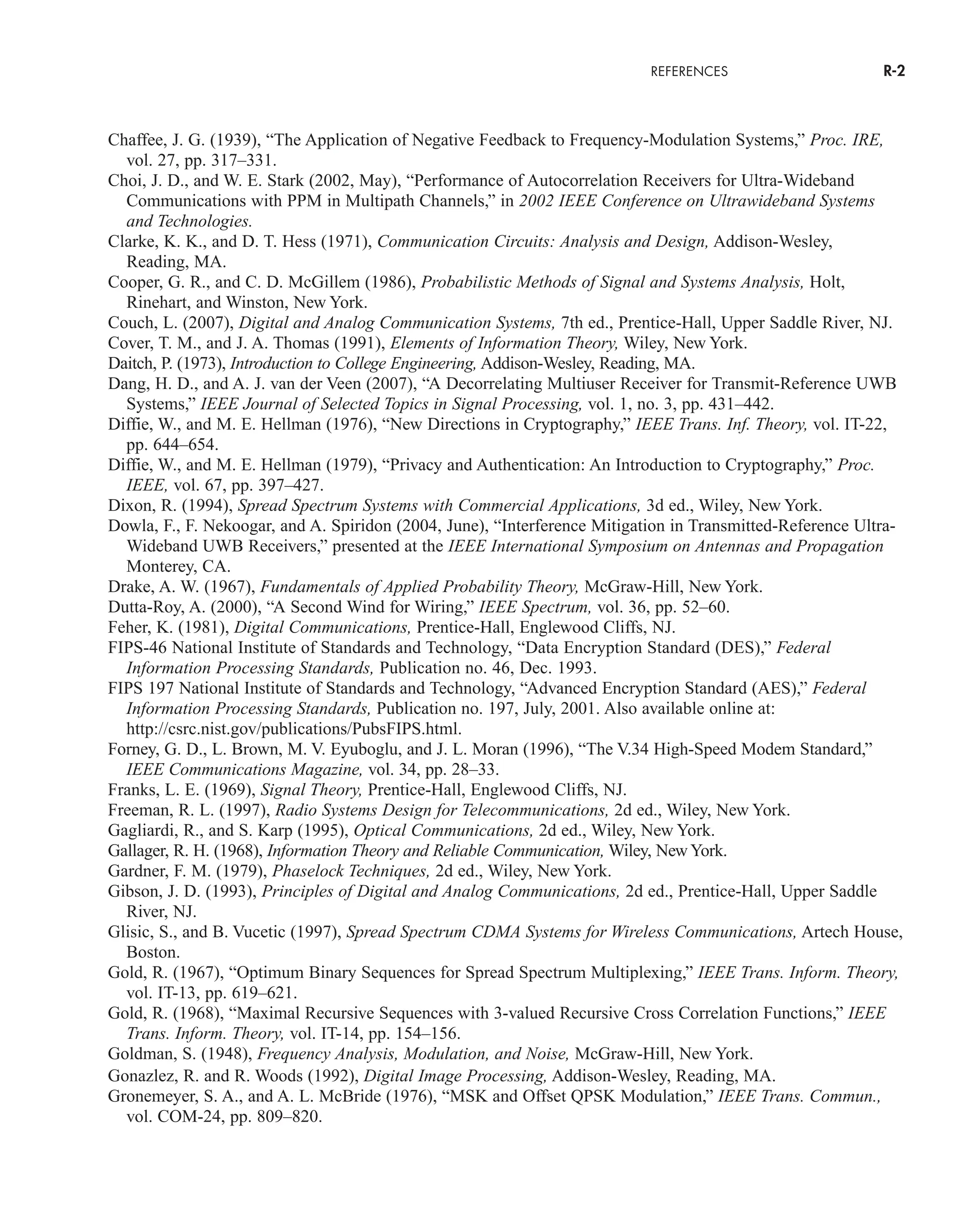

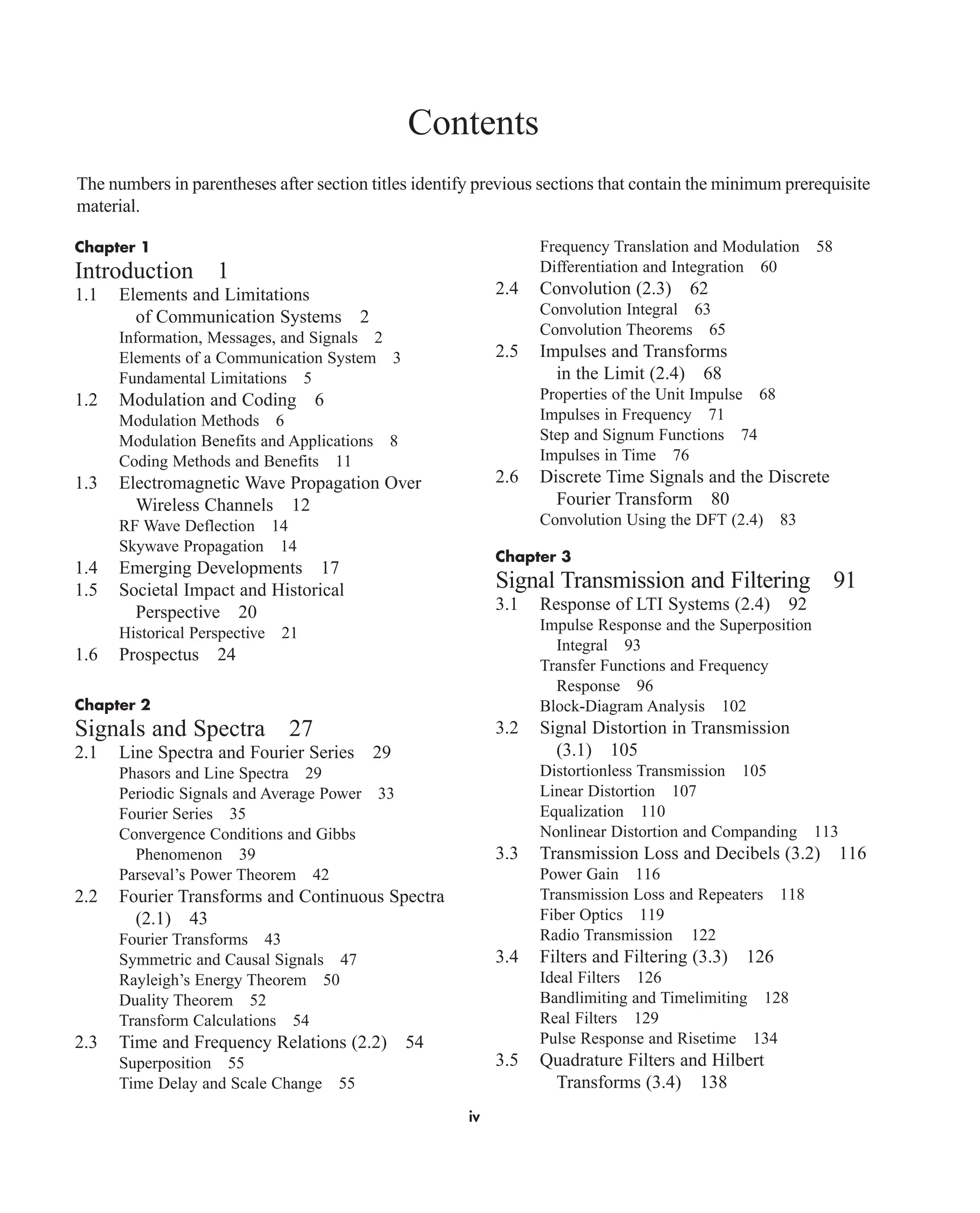

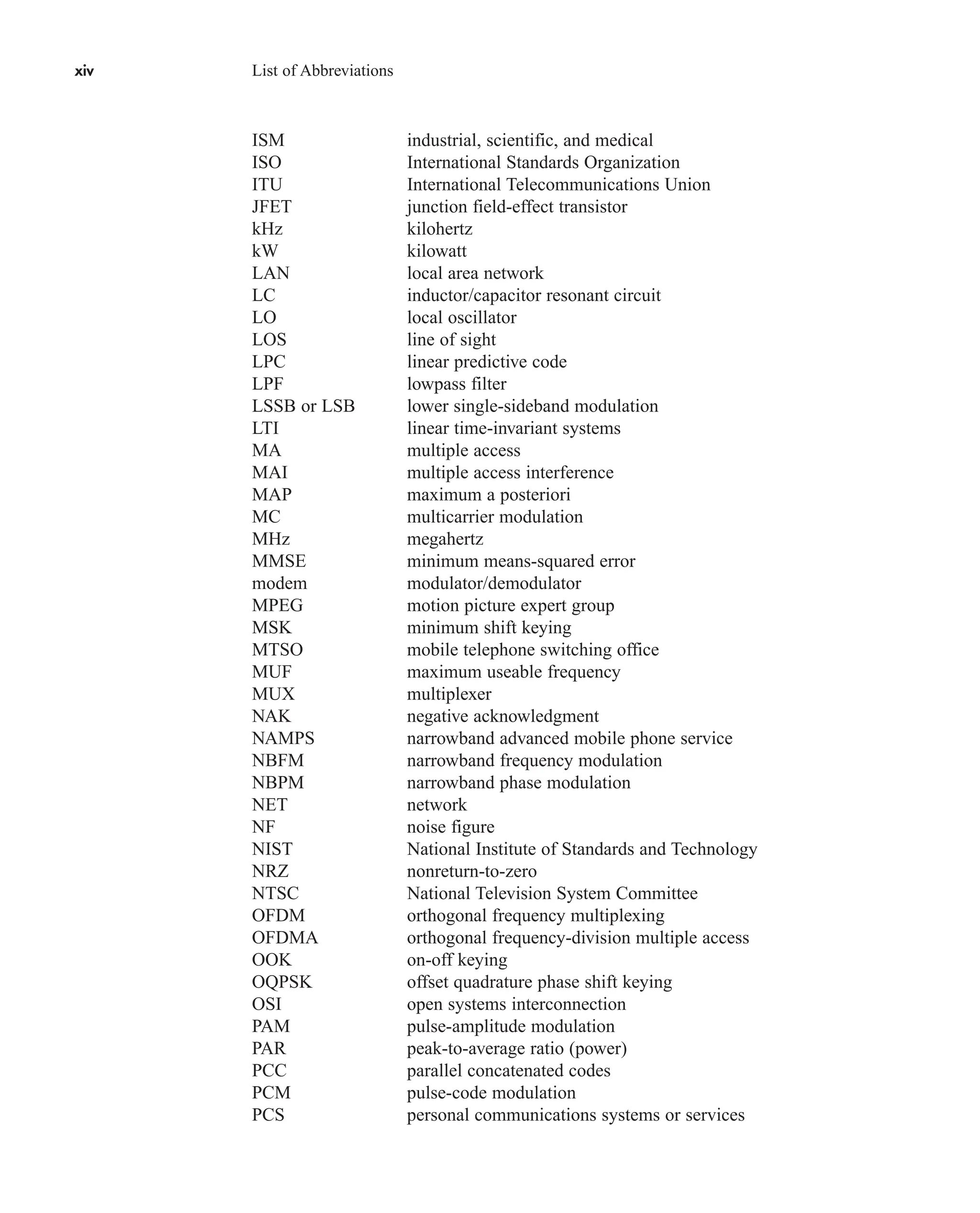

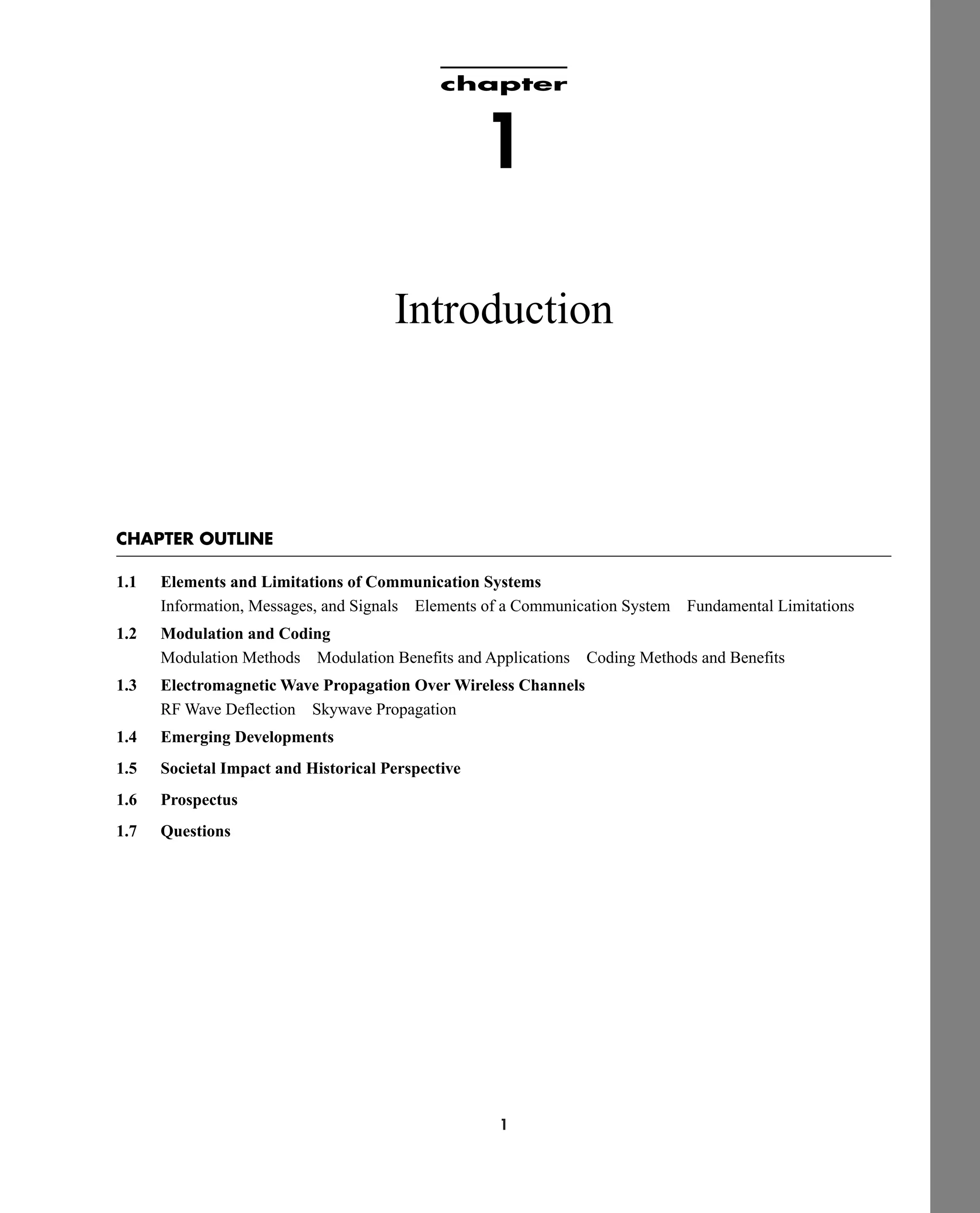

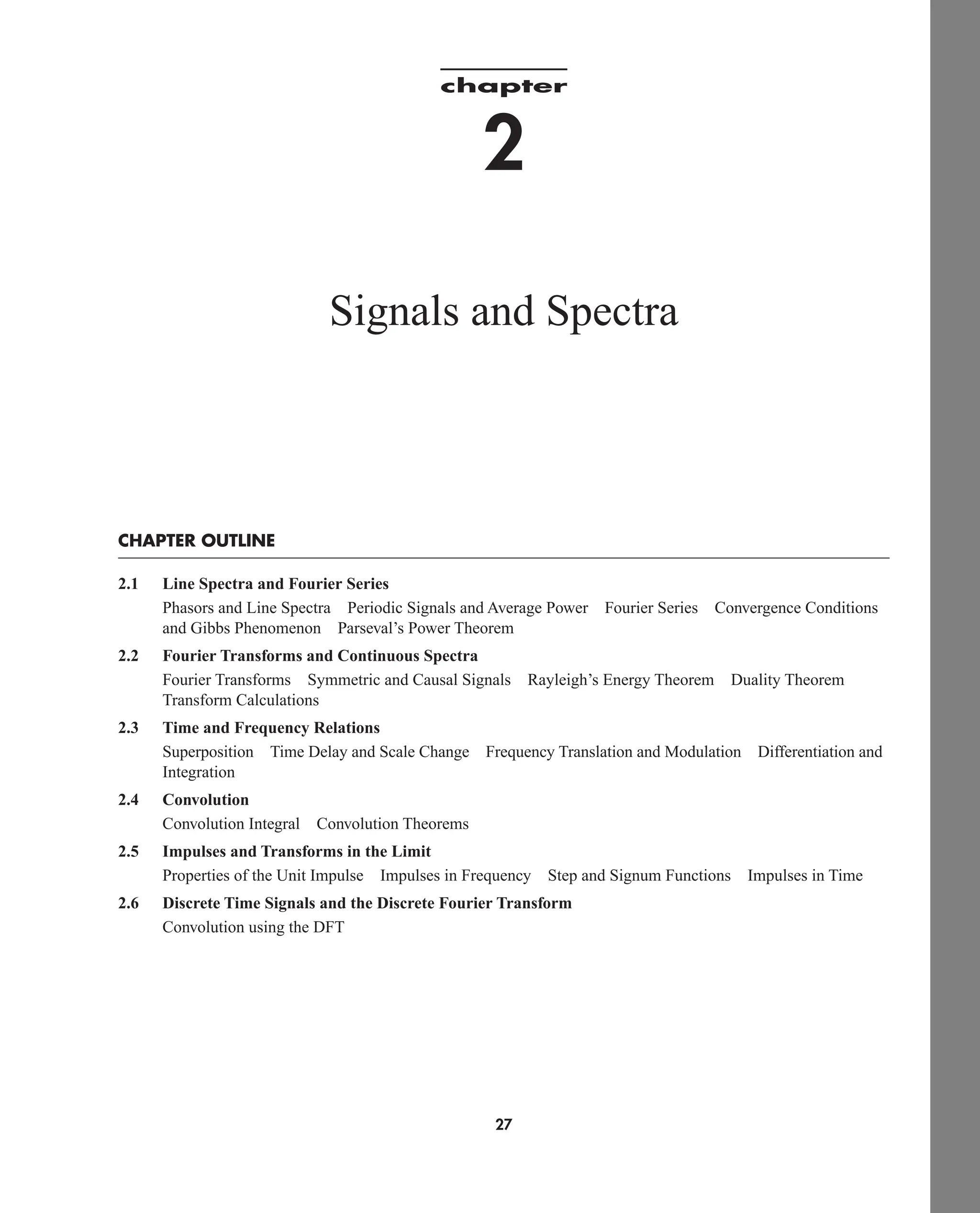

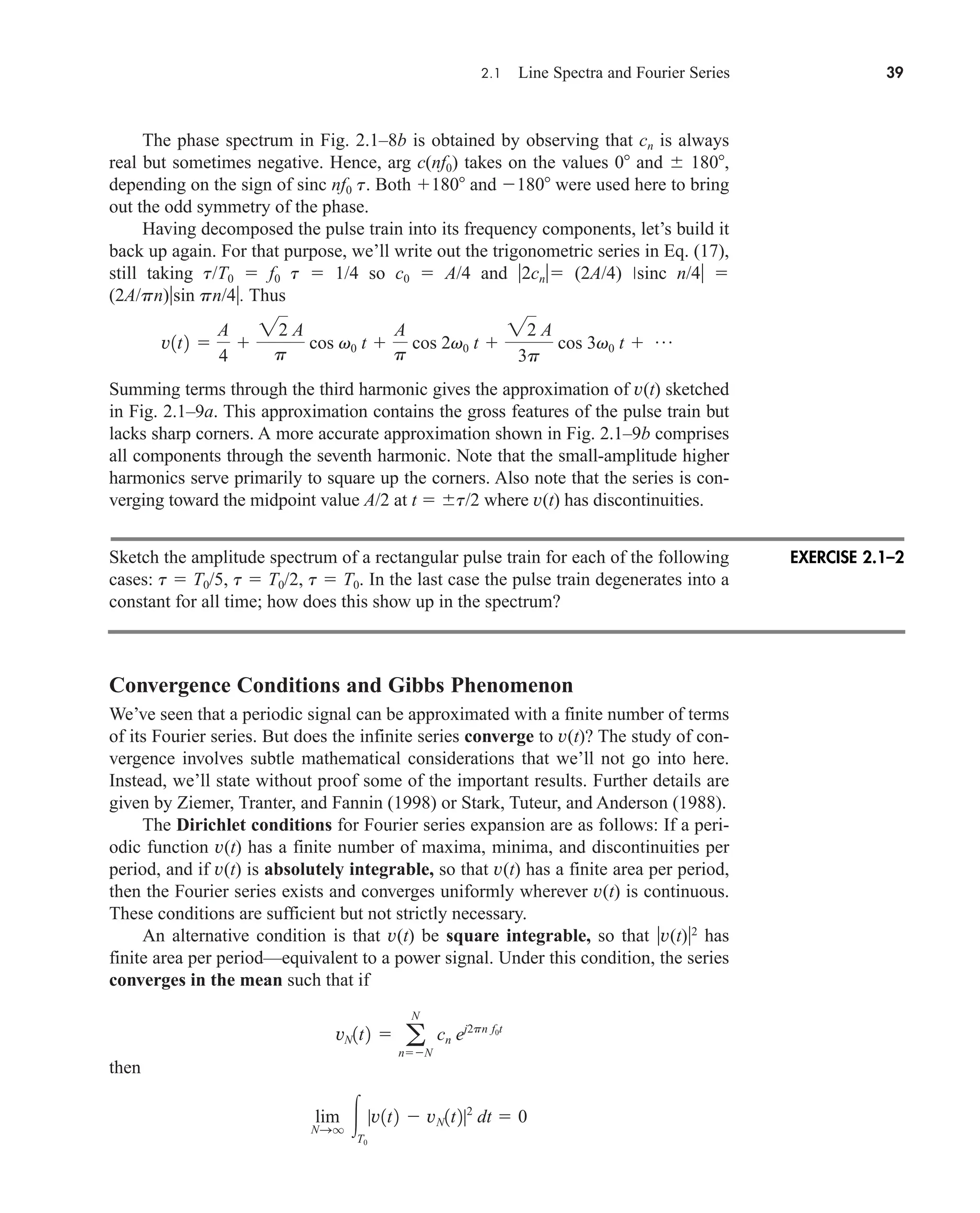

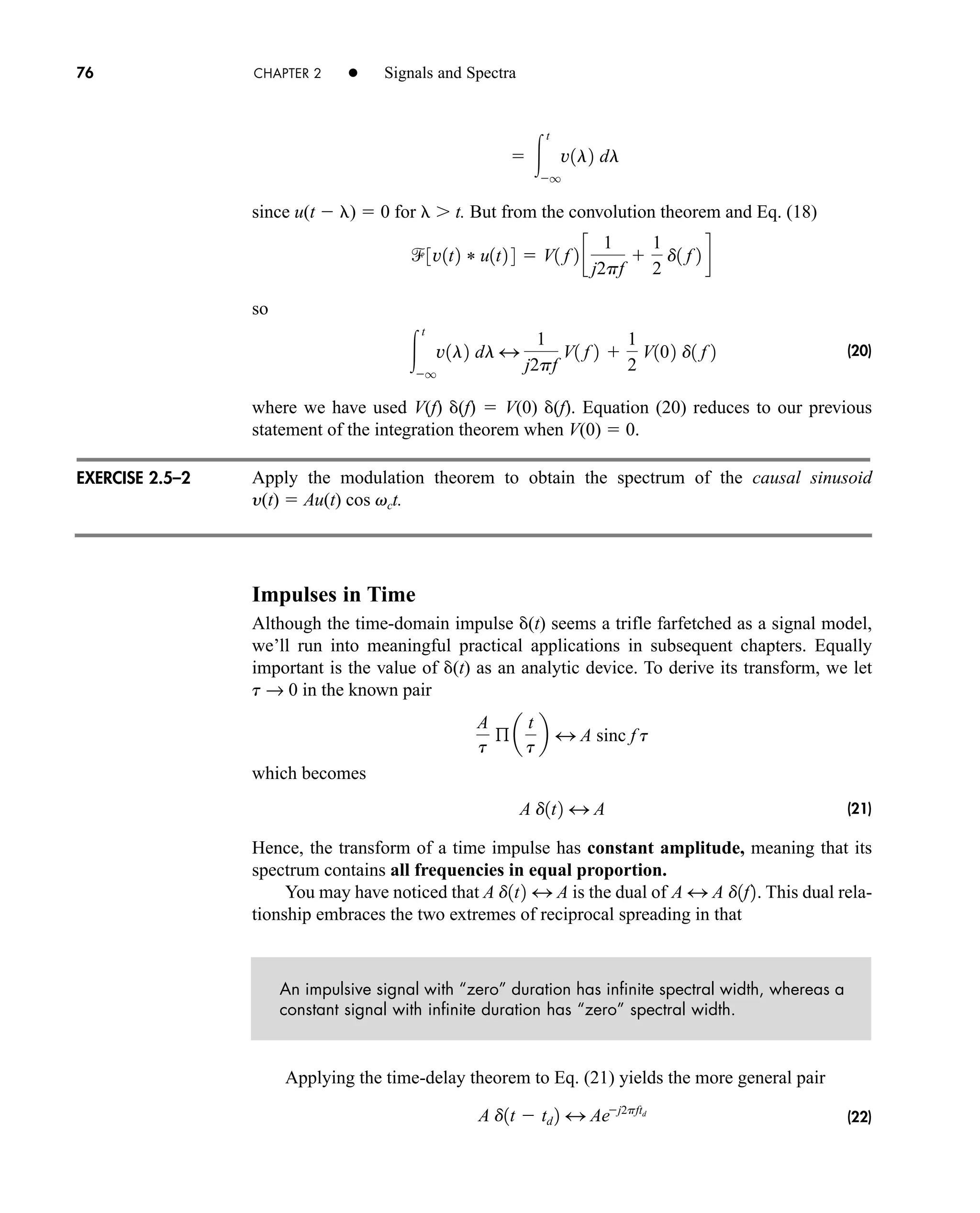

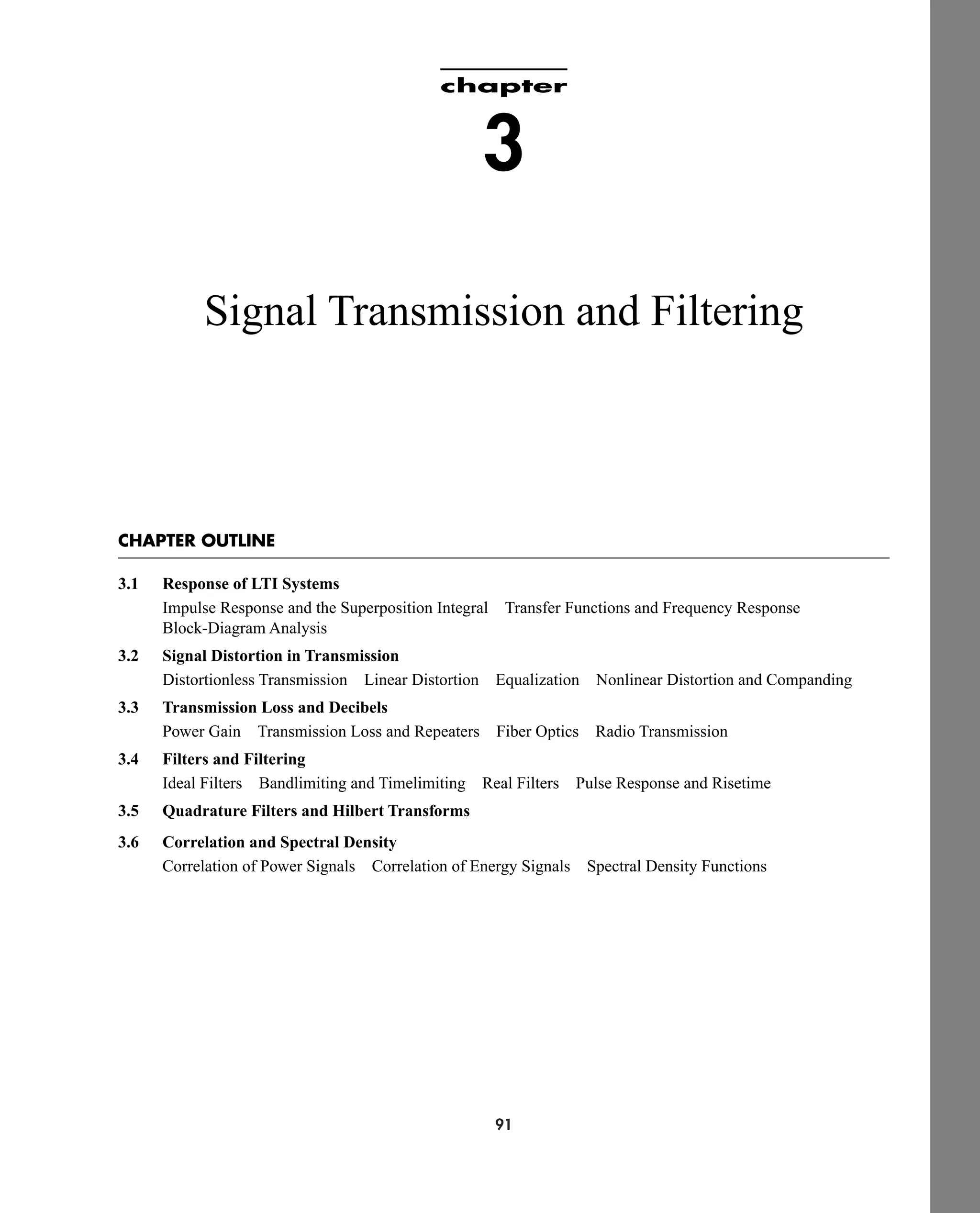

The amplitude spectrum obtained from c(nf0) cn Af0 tsinc nf0 is shown

in Fig. 2.1–8a for the case of /T0 f0 1/4. We construct this plot by drawing the

continuous function Af0 tsinc ft as a dashed curve, which becomes the envelope of

the lines. The spectral lines at 4f0, 8f0, and so on, are “missing” since they fall

precisely at multiples of 1/t where the envelope equals zero. The dc component has

amplitude c(0) At/T0 which should be recognized as the average value of v(t) by

inspection of Fig. 2.1–7. Incidentally, t/T0 equals the ratio of “on” time to period,

frequently designated as the duty cycle in pulse electronics work.

cn

At

T0

sinc nf0 t

A

T0

sin pnf0 t

pnf0

A

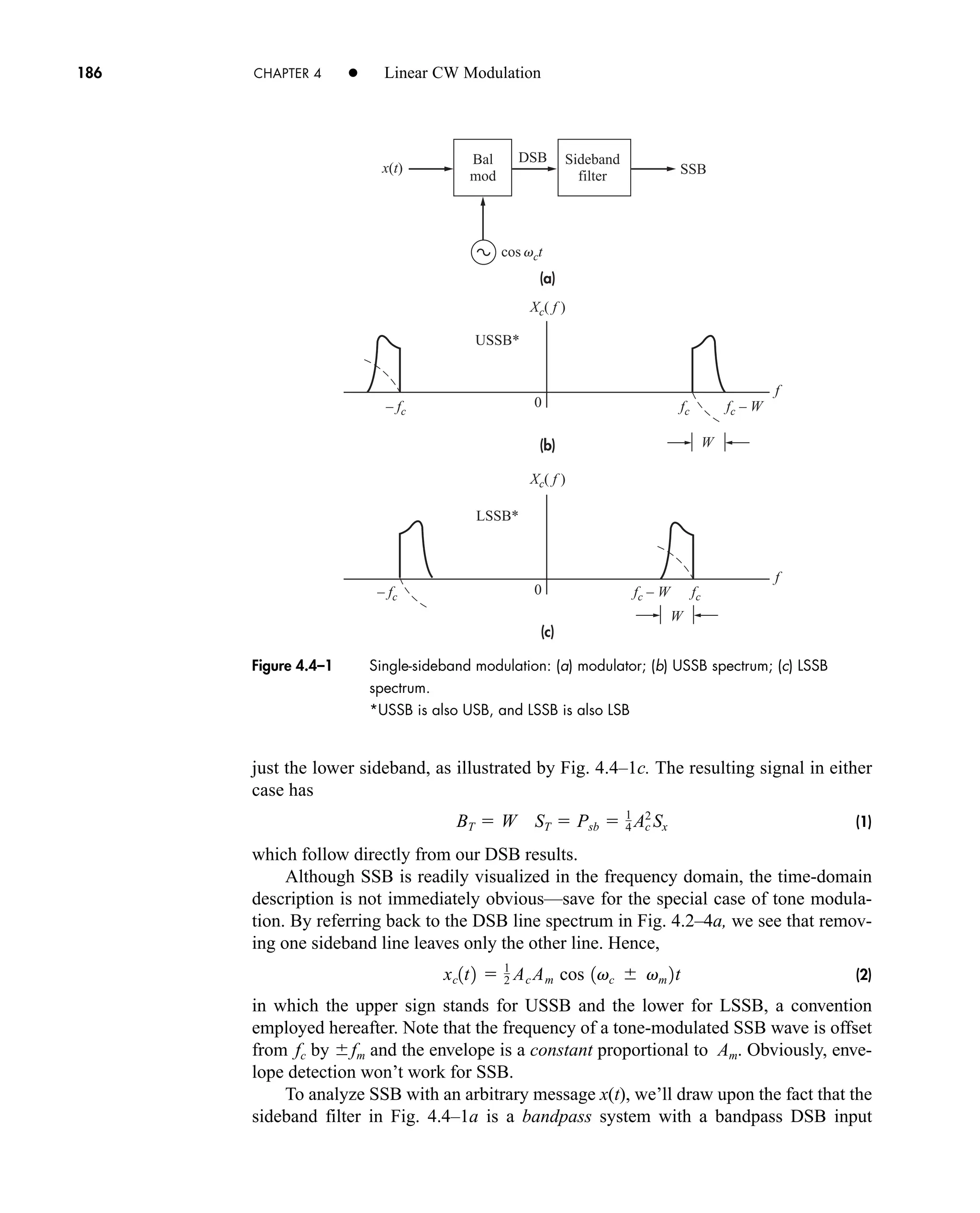

j2pnf0 T0

1ejpn f0t

ejpn f0t

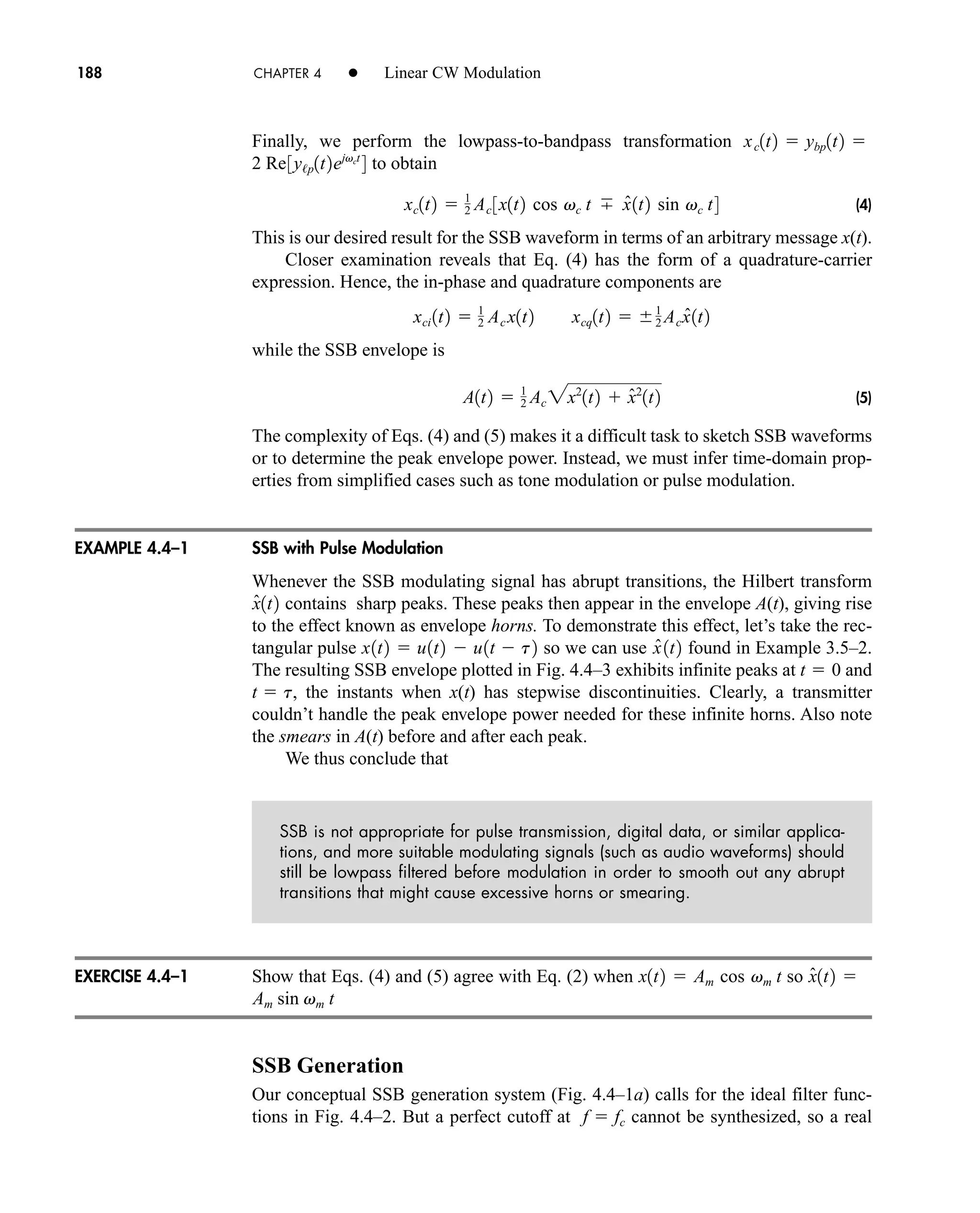

2

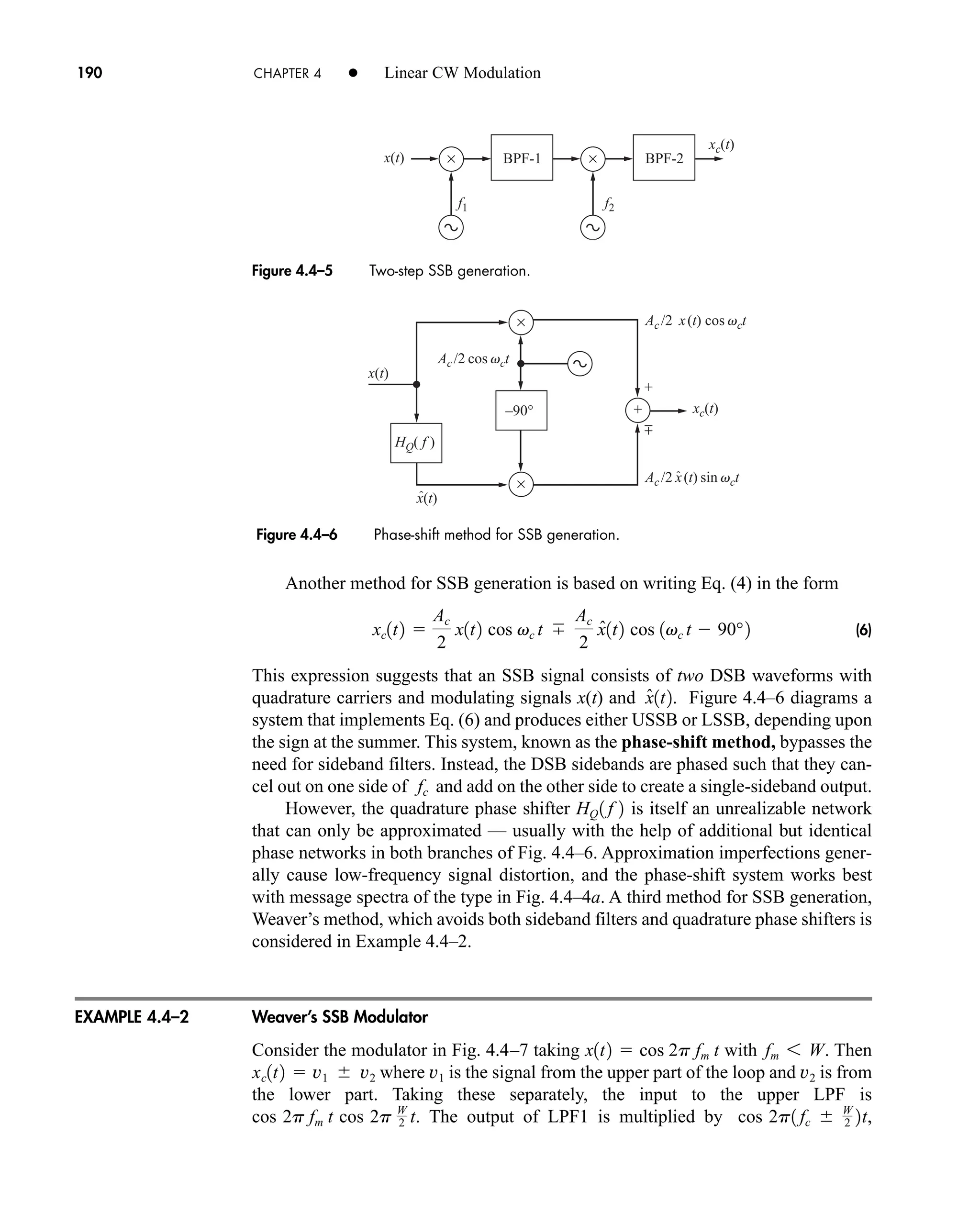

Figure 2.1–7 Rectangular pulse train.

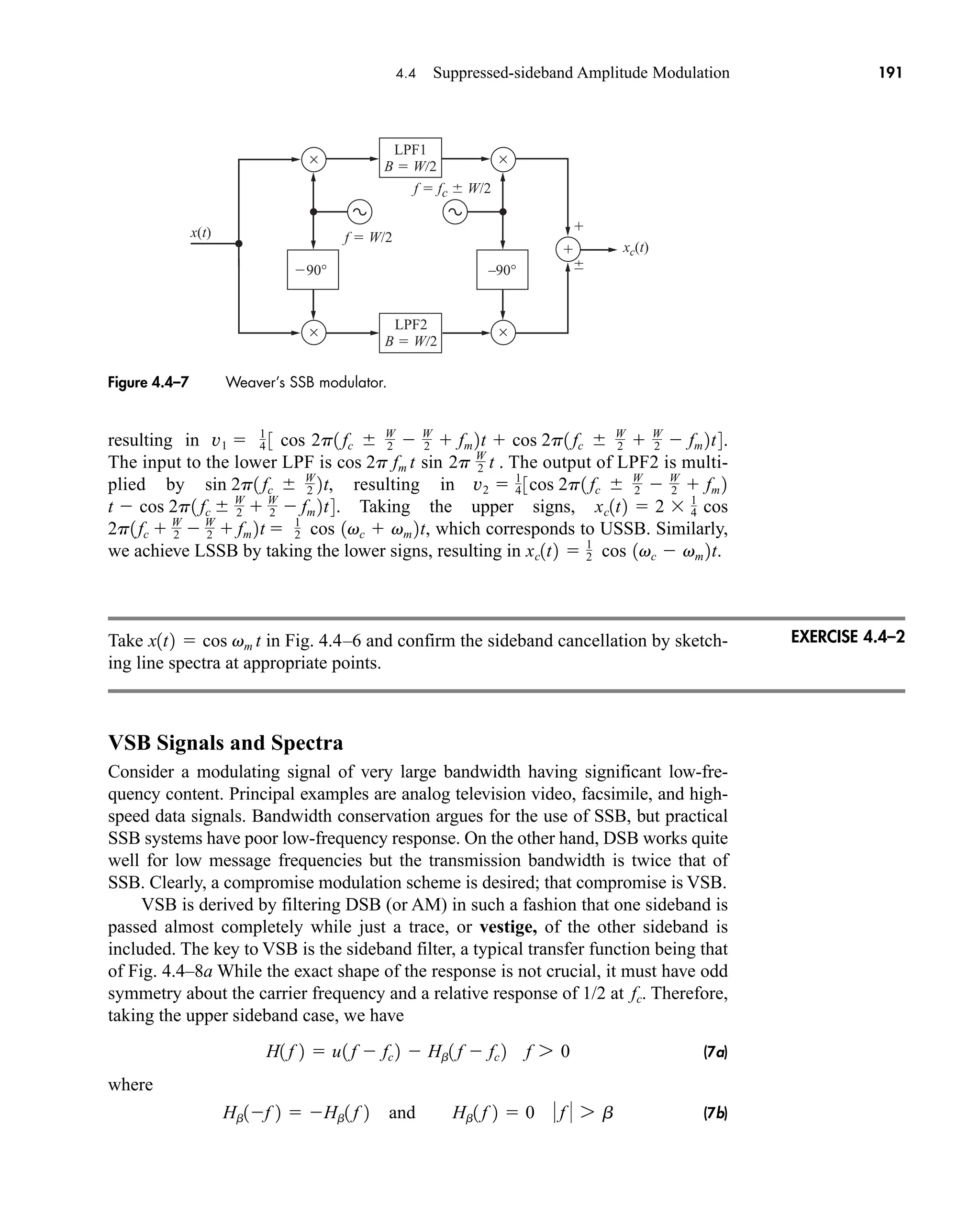

v(t)

0 T0

– T0 –

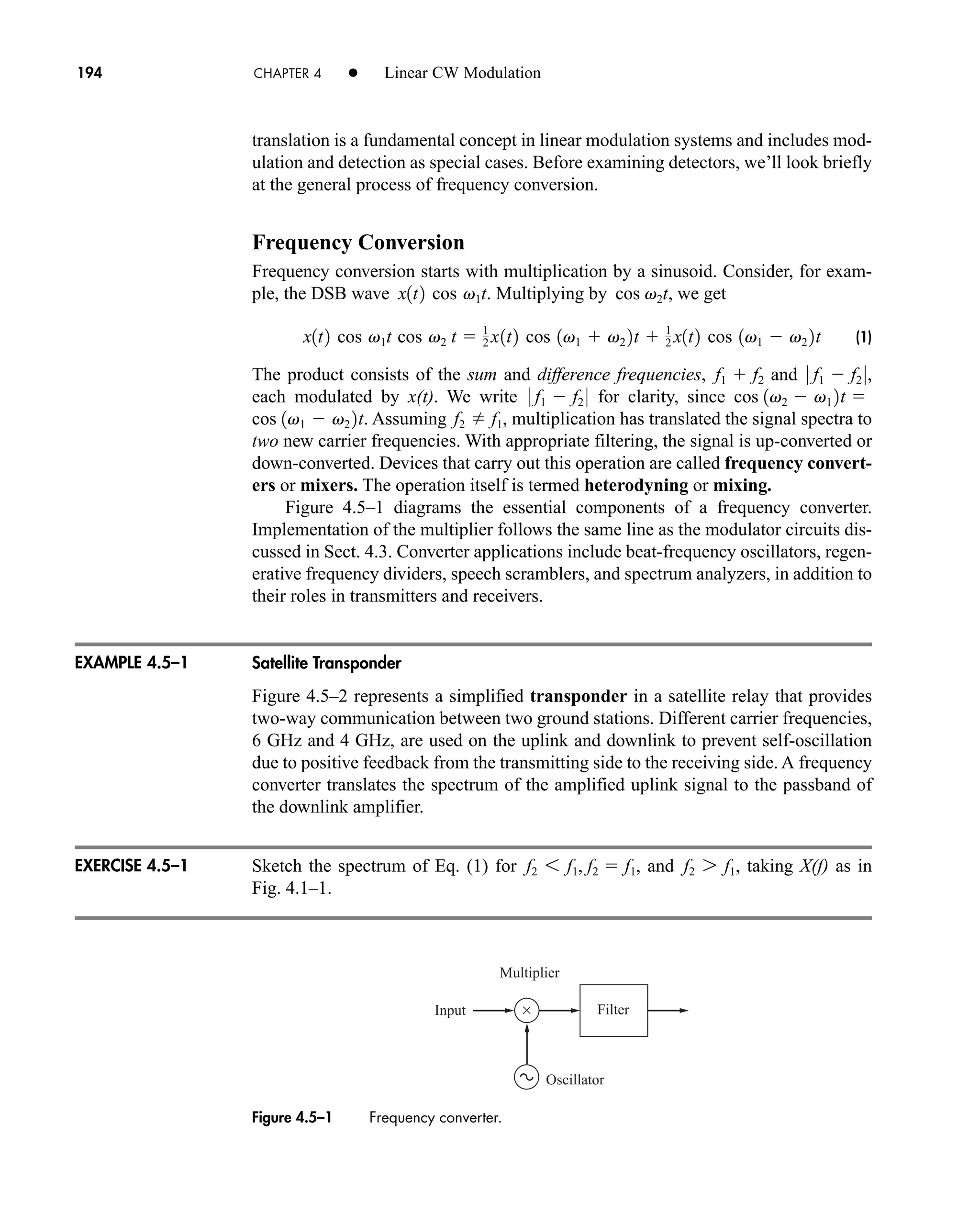

A

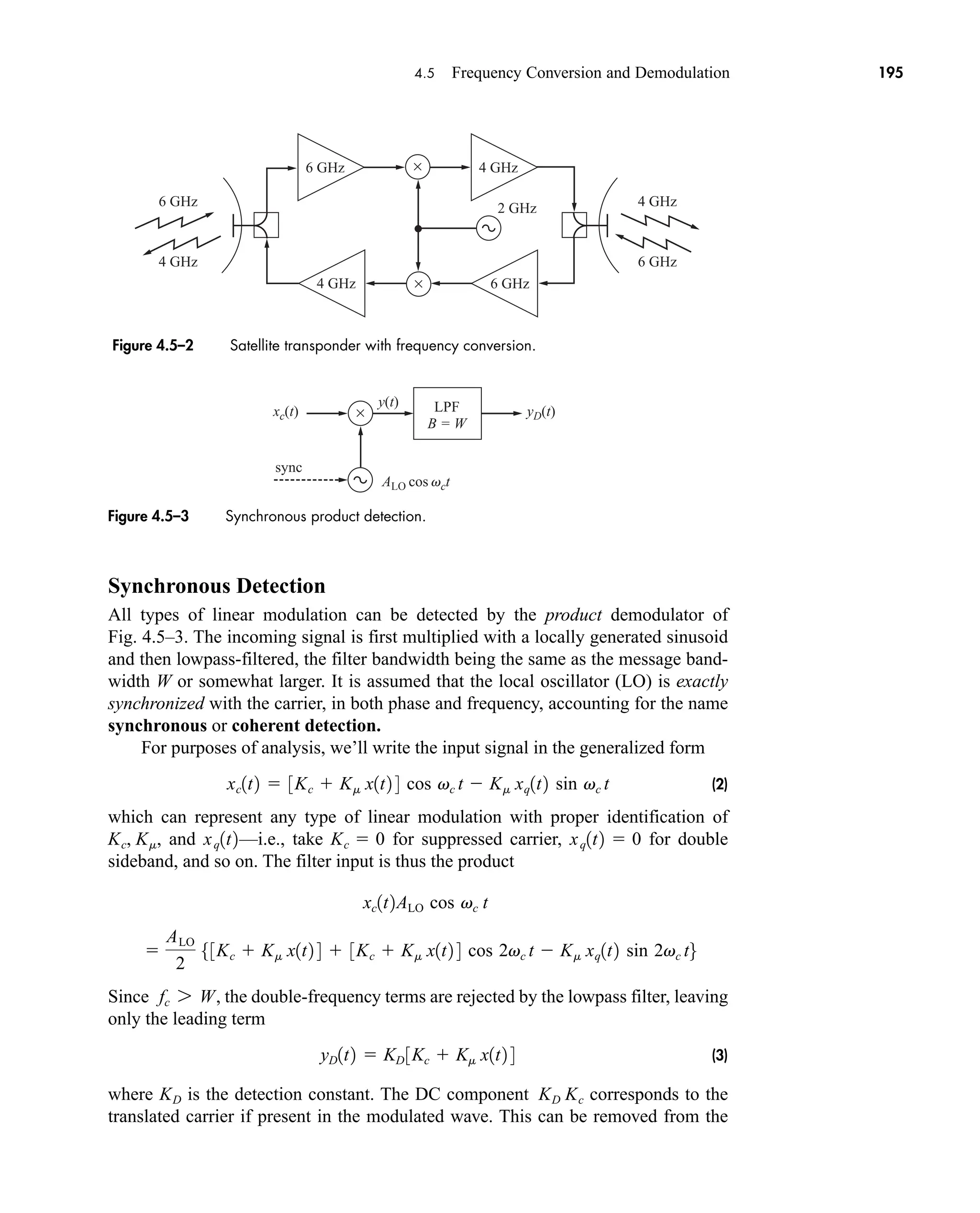

t

t

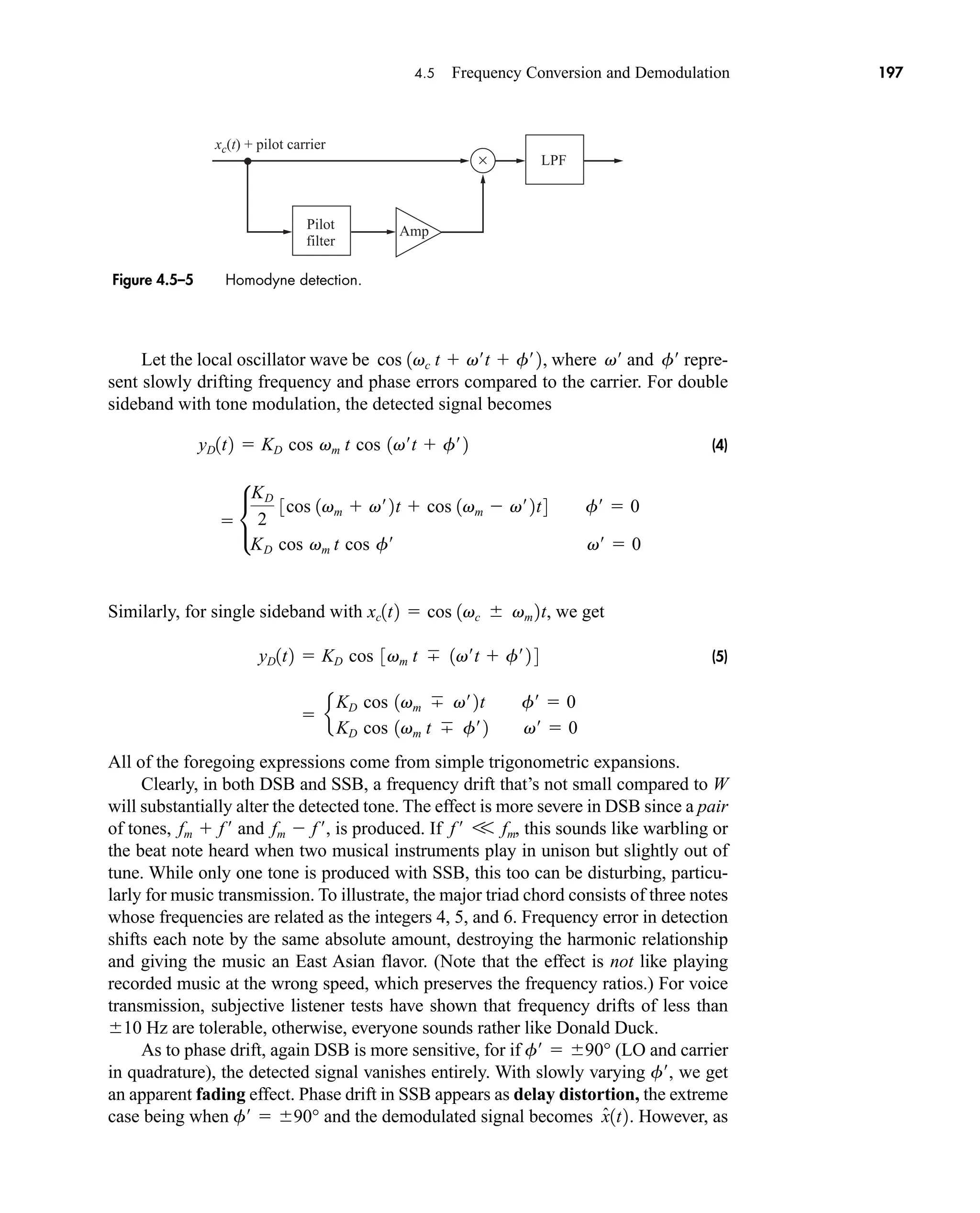

2

t

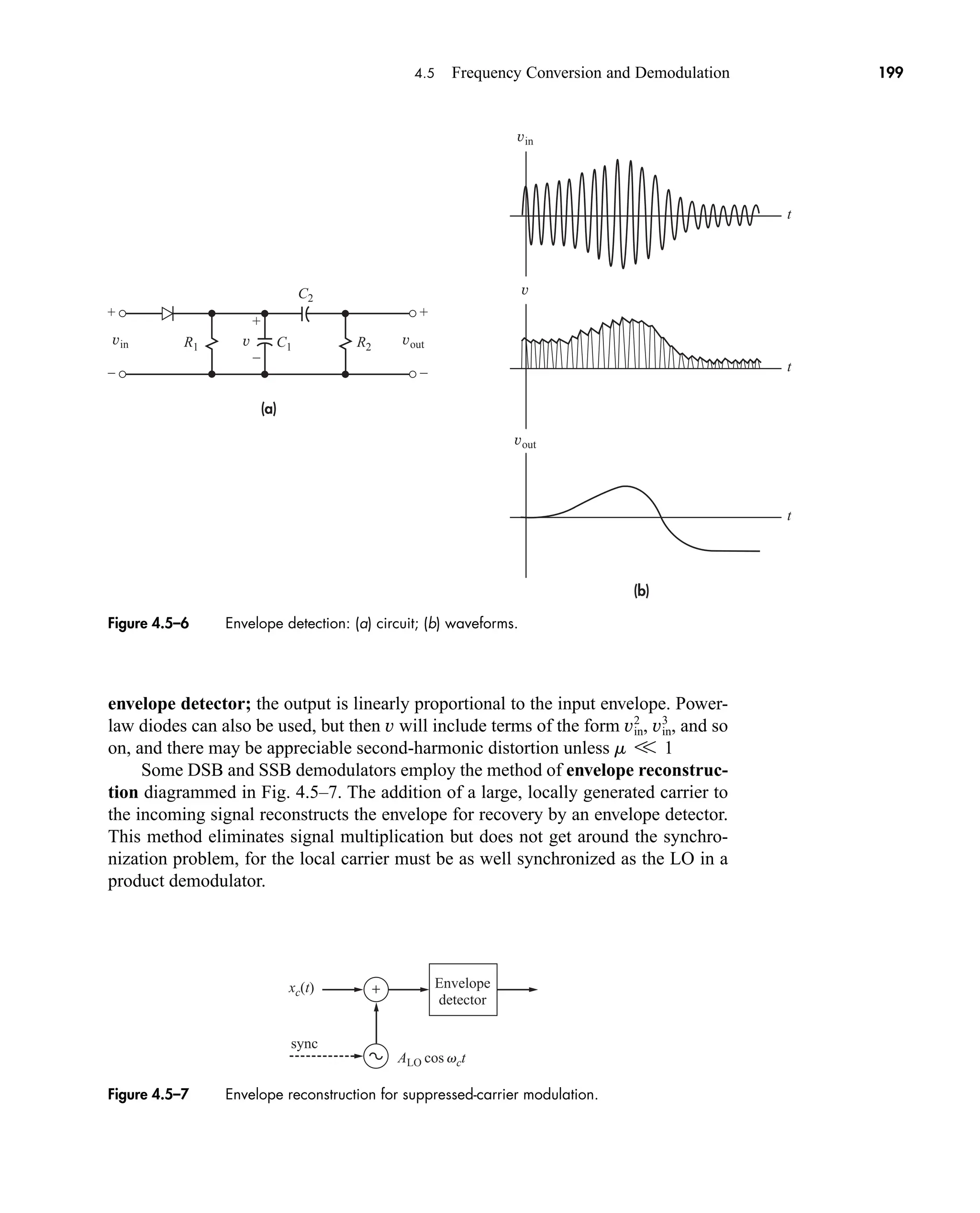

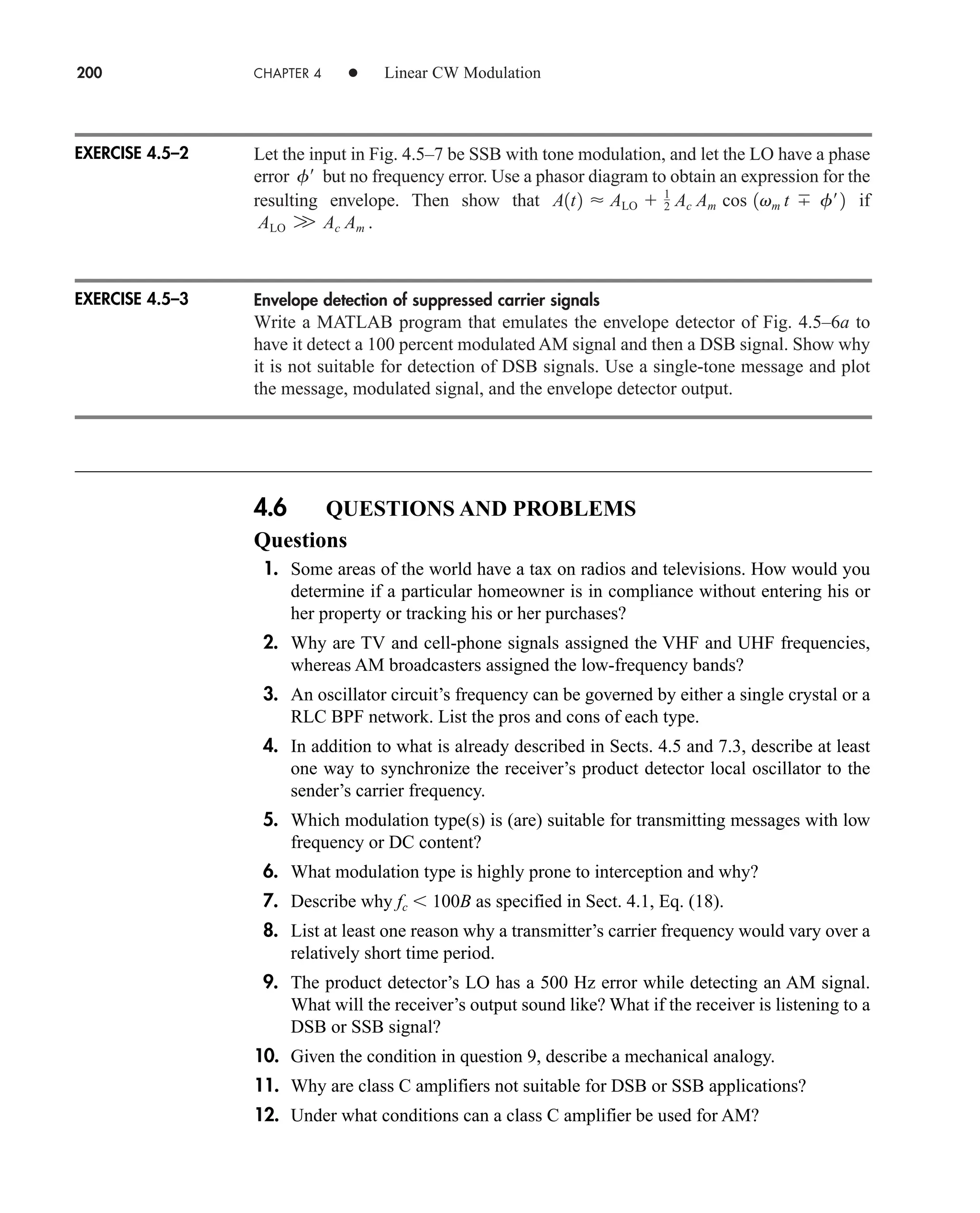

2

Figure 2.1–8 Spectrum of rectangular pulse train with fct 1/4. (a) Amplitude; (b) phase.

(a)

(b)

180°

–180°

A f0t

– f0 2 f0

= 4 f0

f0

A f0t|sinc ft|

|c(nf0)|

arg [c( f0)]

f

0

0

– t

1

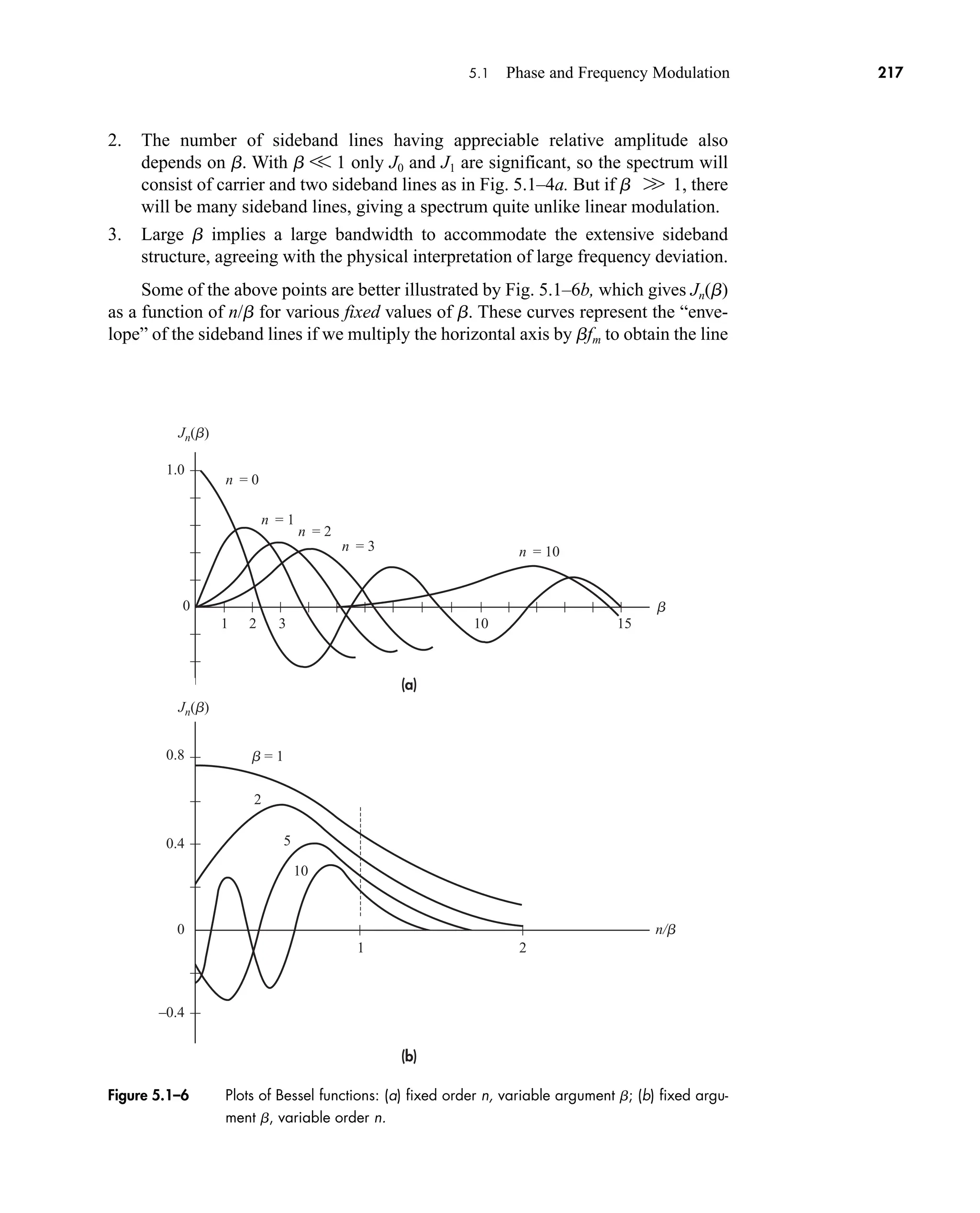

t

1

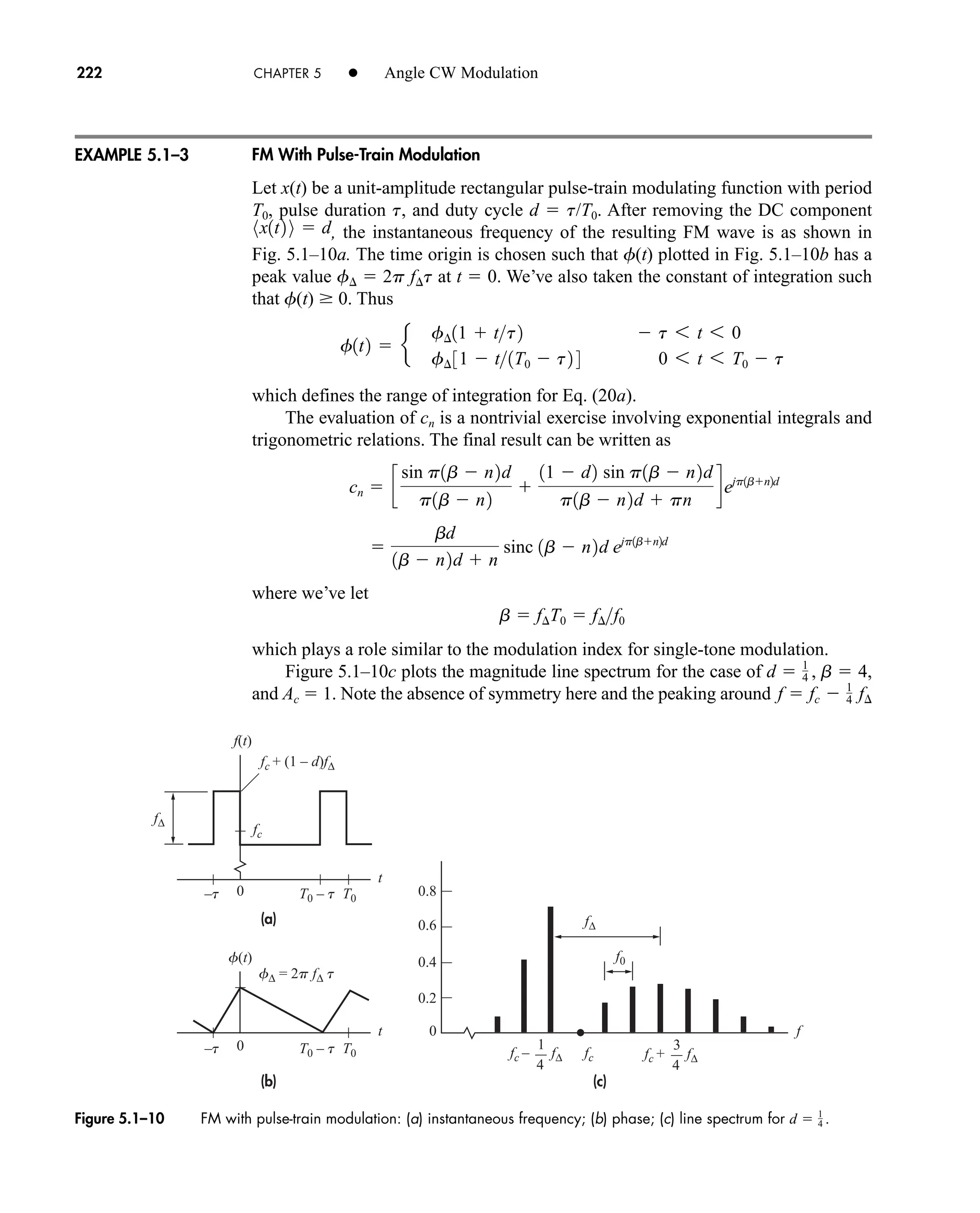

t

2

t

3

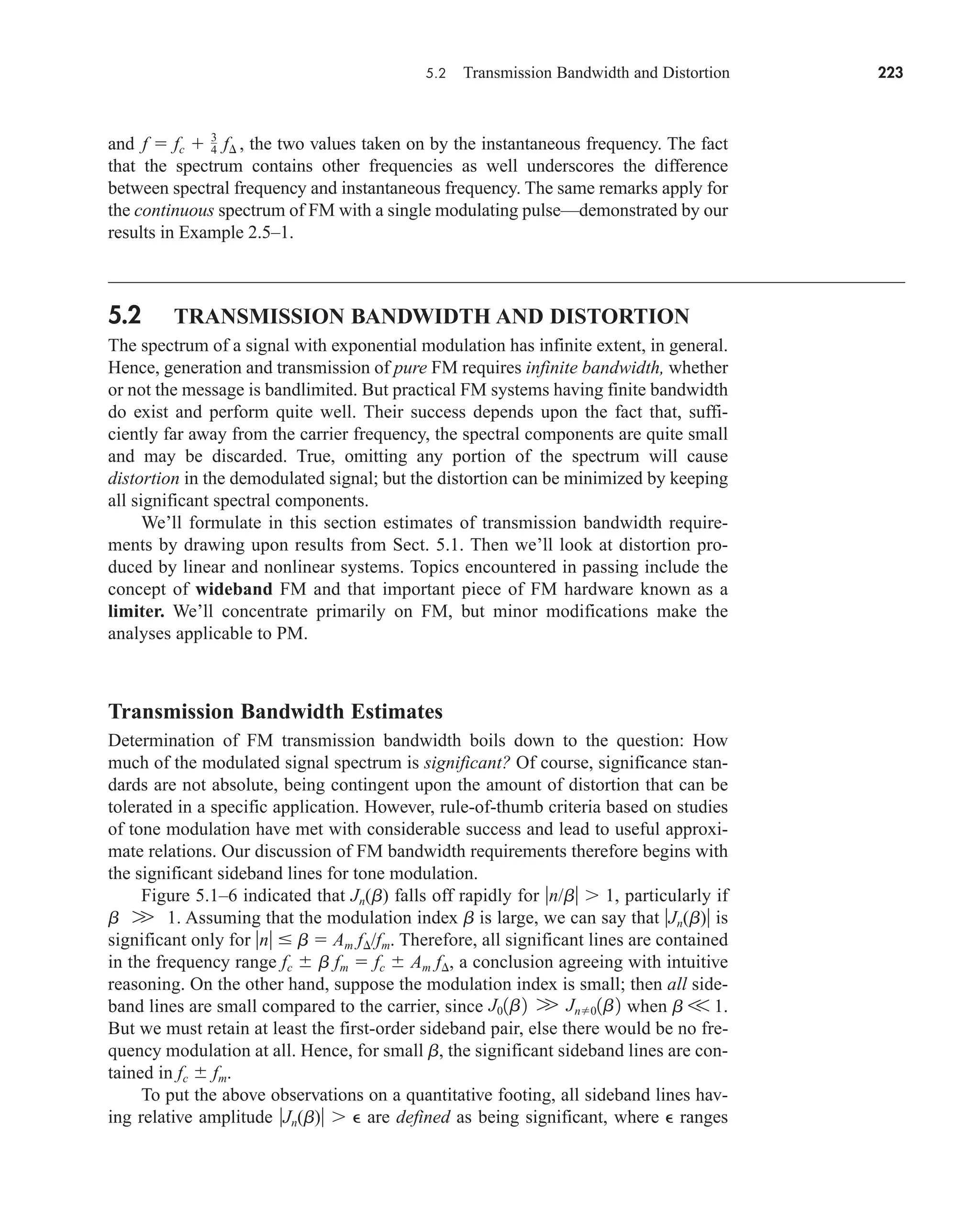

t

4

t

2

t

1

t

3

t

4

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:03 PM Page 38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-60-2048.jpg)

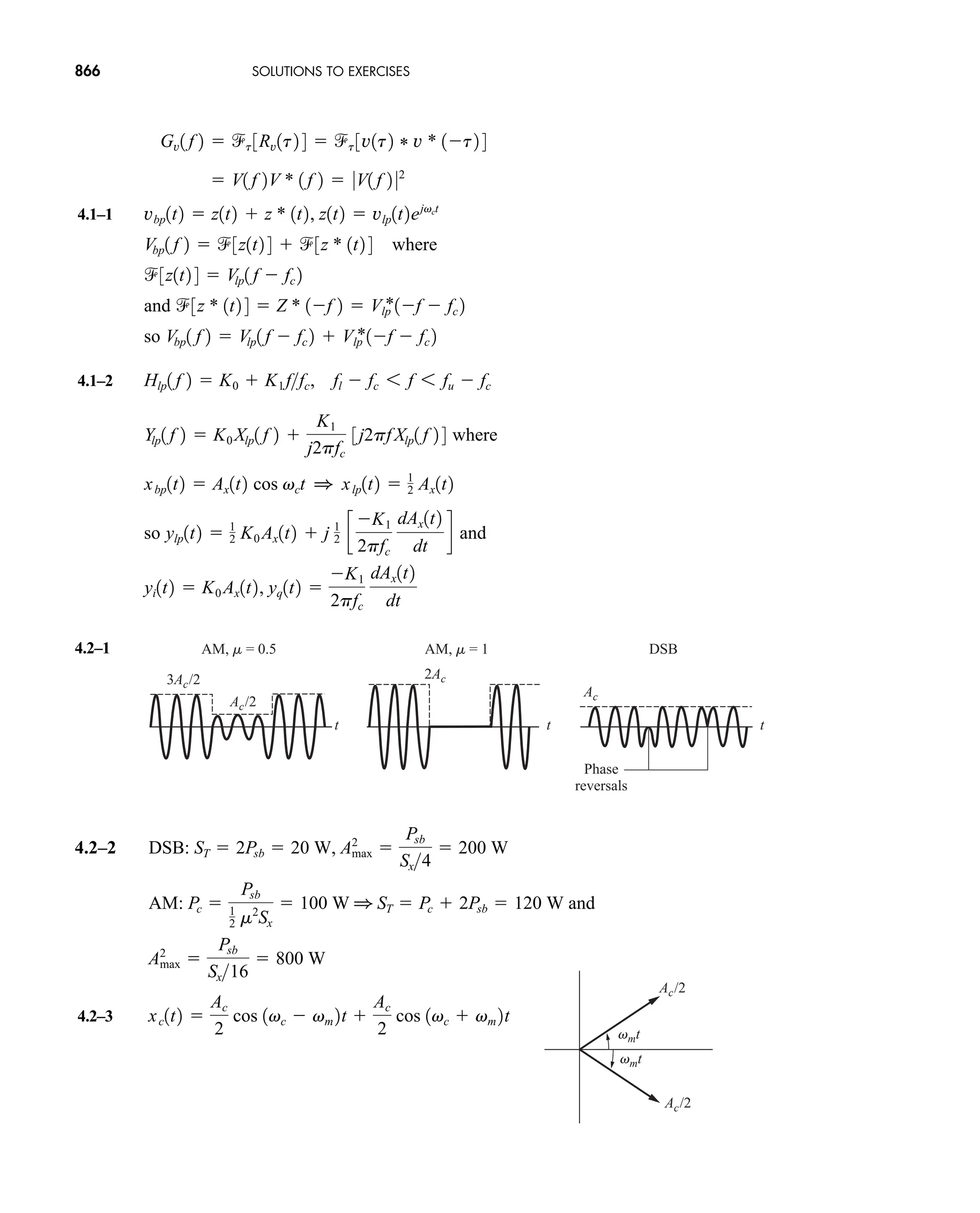

![2.2 Fourier Transforms and Continuous Spectra 53

Although the statement of duality in Eq. (18) seems somewhat abstract, it turns

out to be a handy way of generating new transform pairs without the labor of inte-

gration. The theorem works best when y(t) is real and even so z(t) will also be real

and even, and The following example should clar-

ify the procedure.

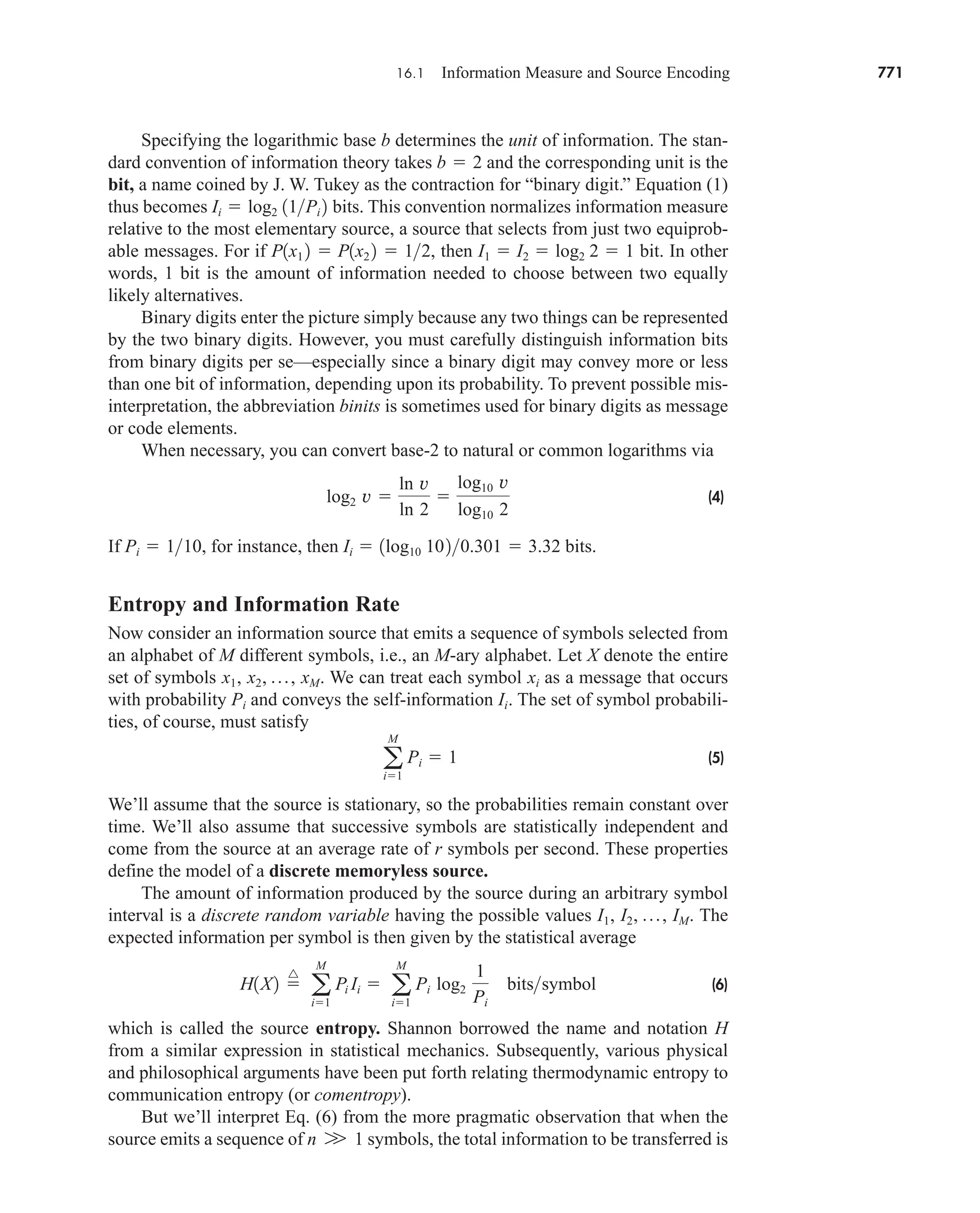

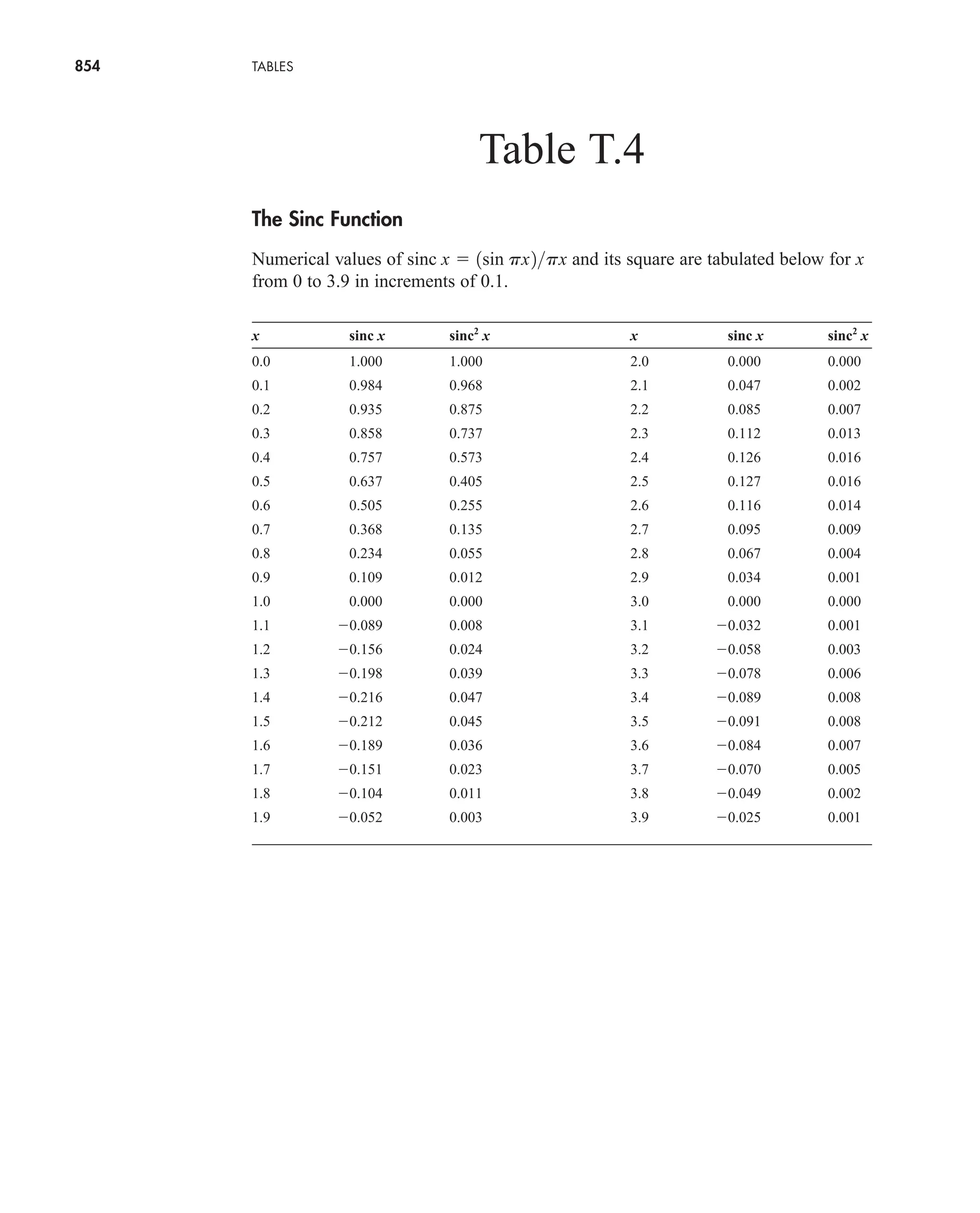

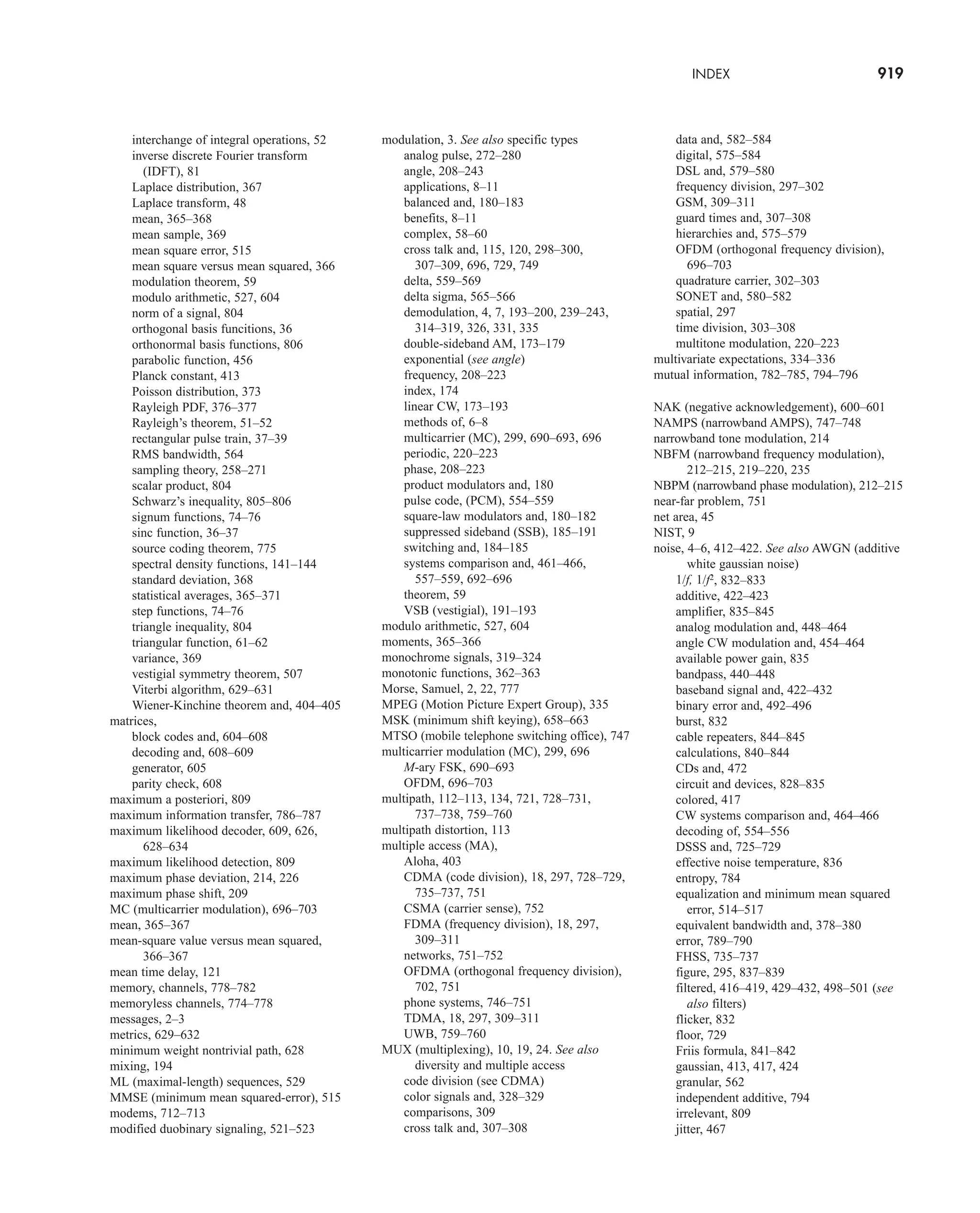

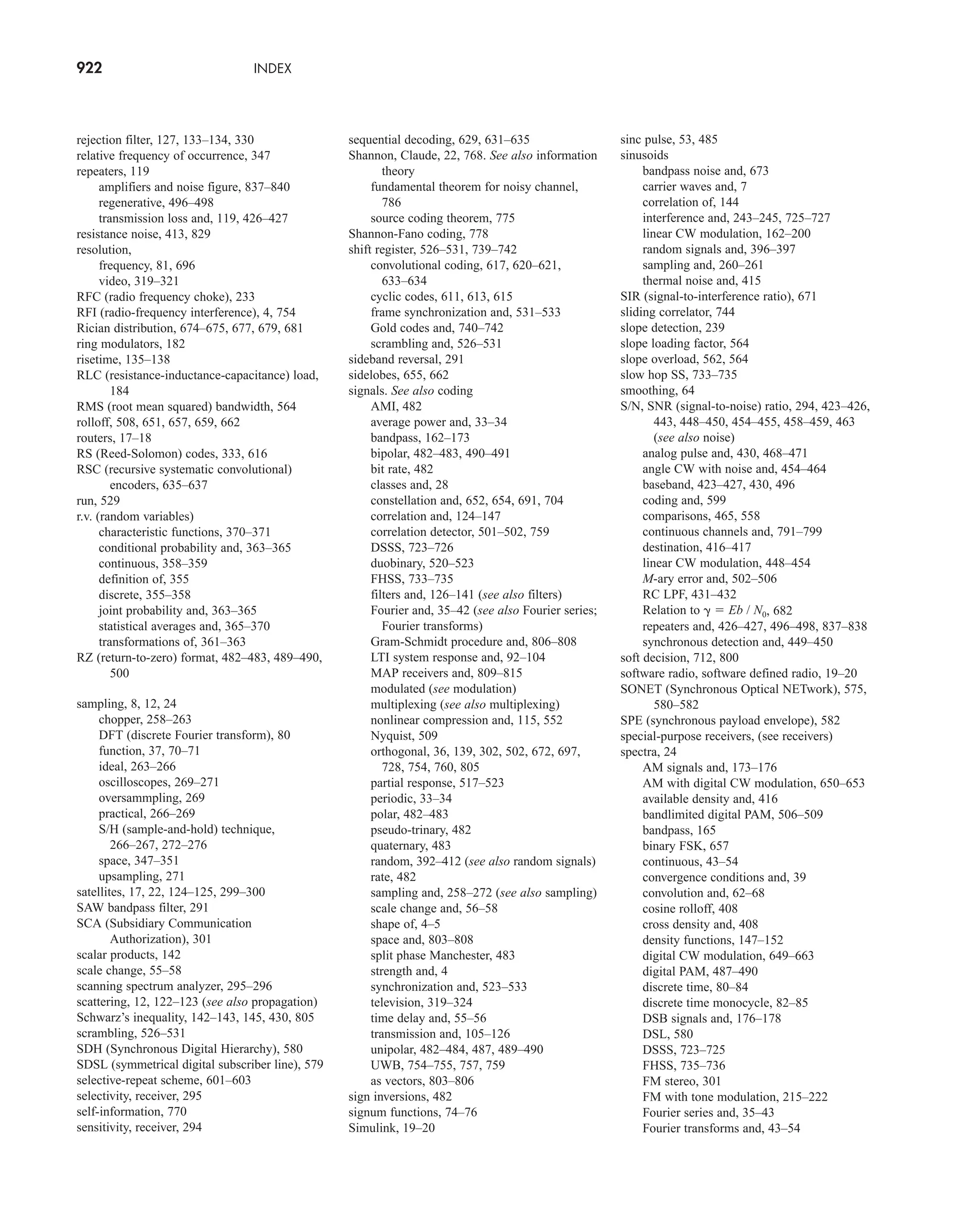

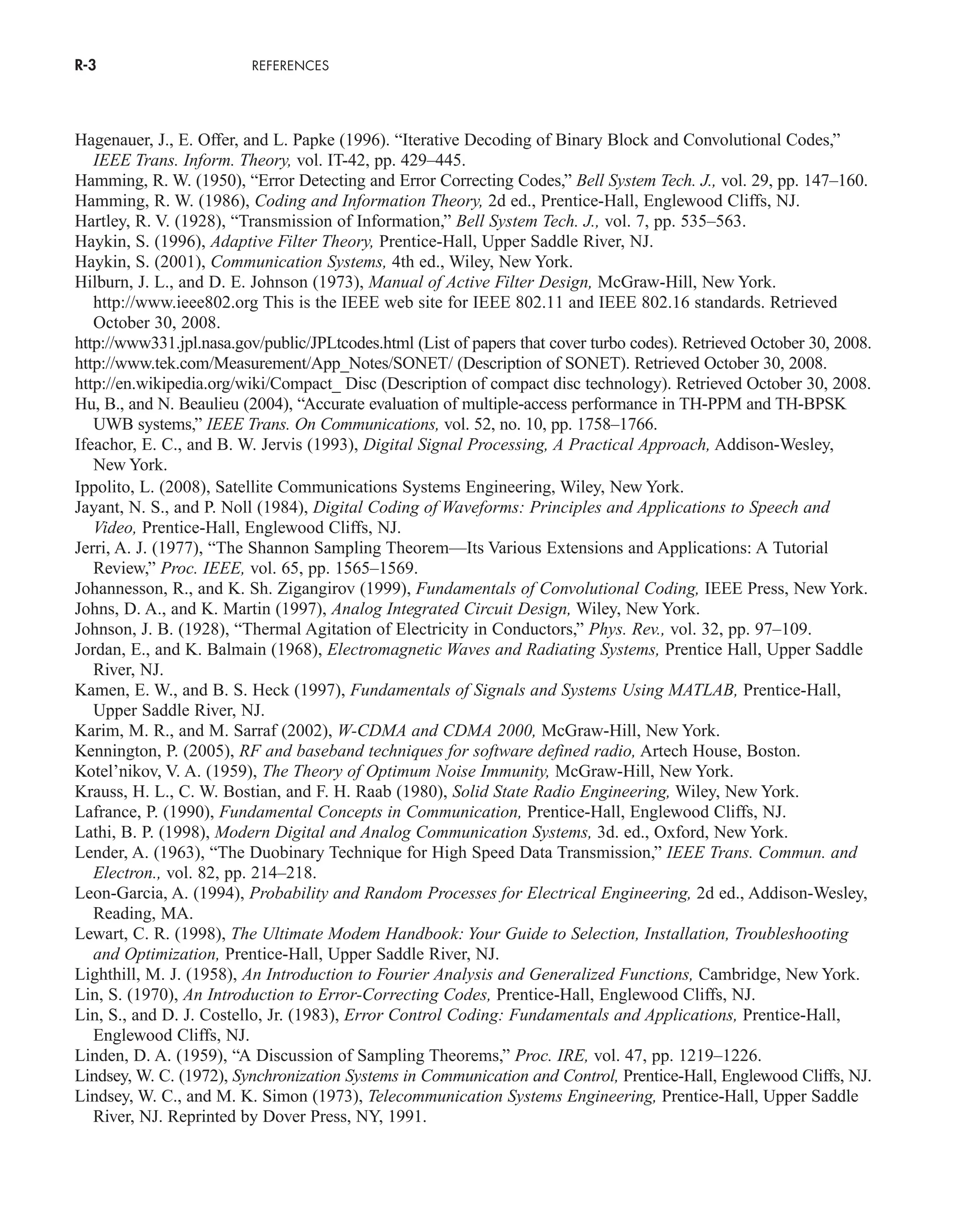

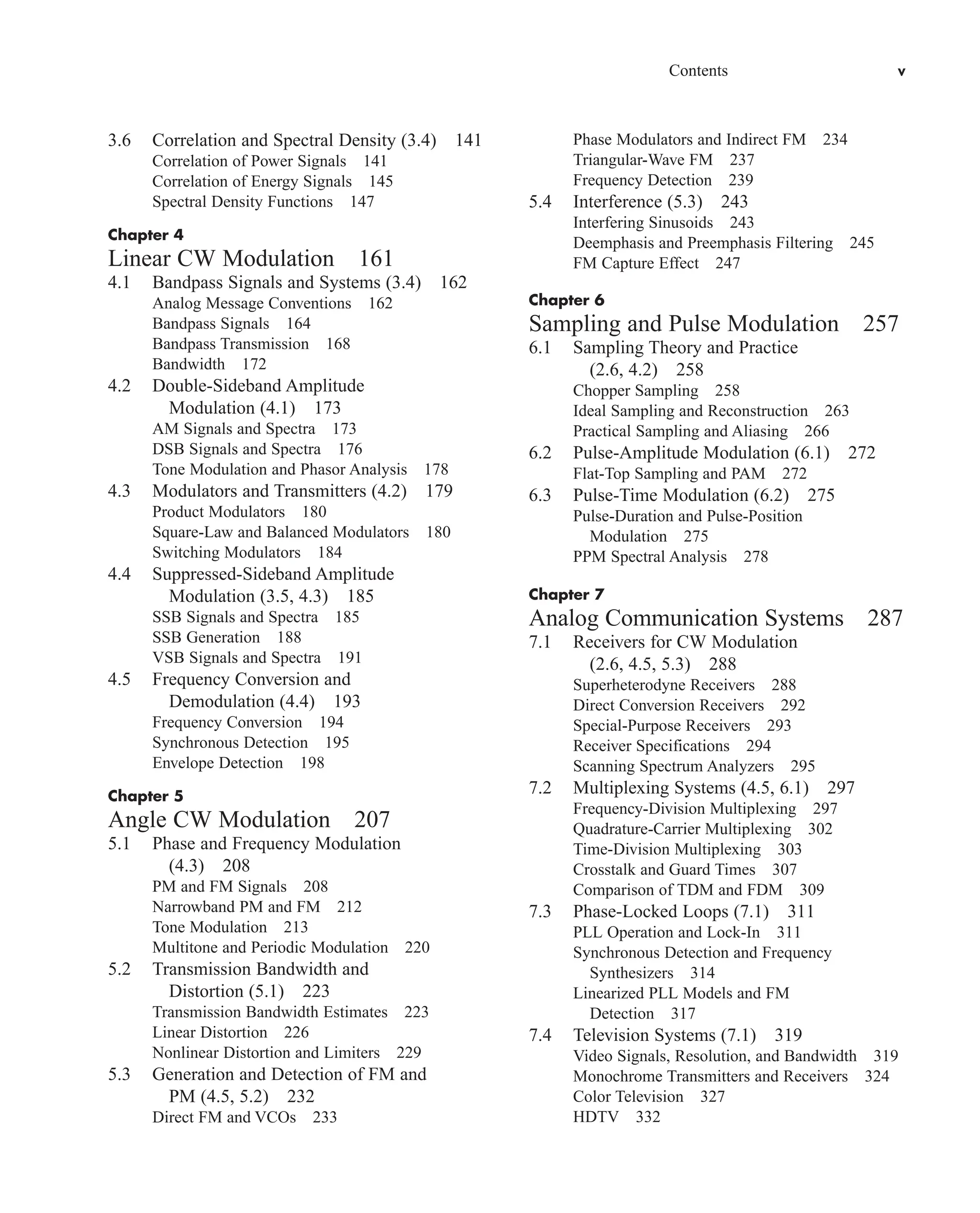

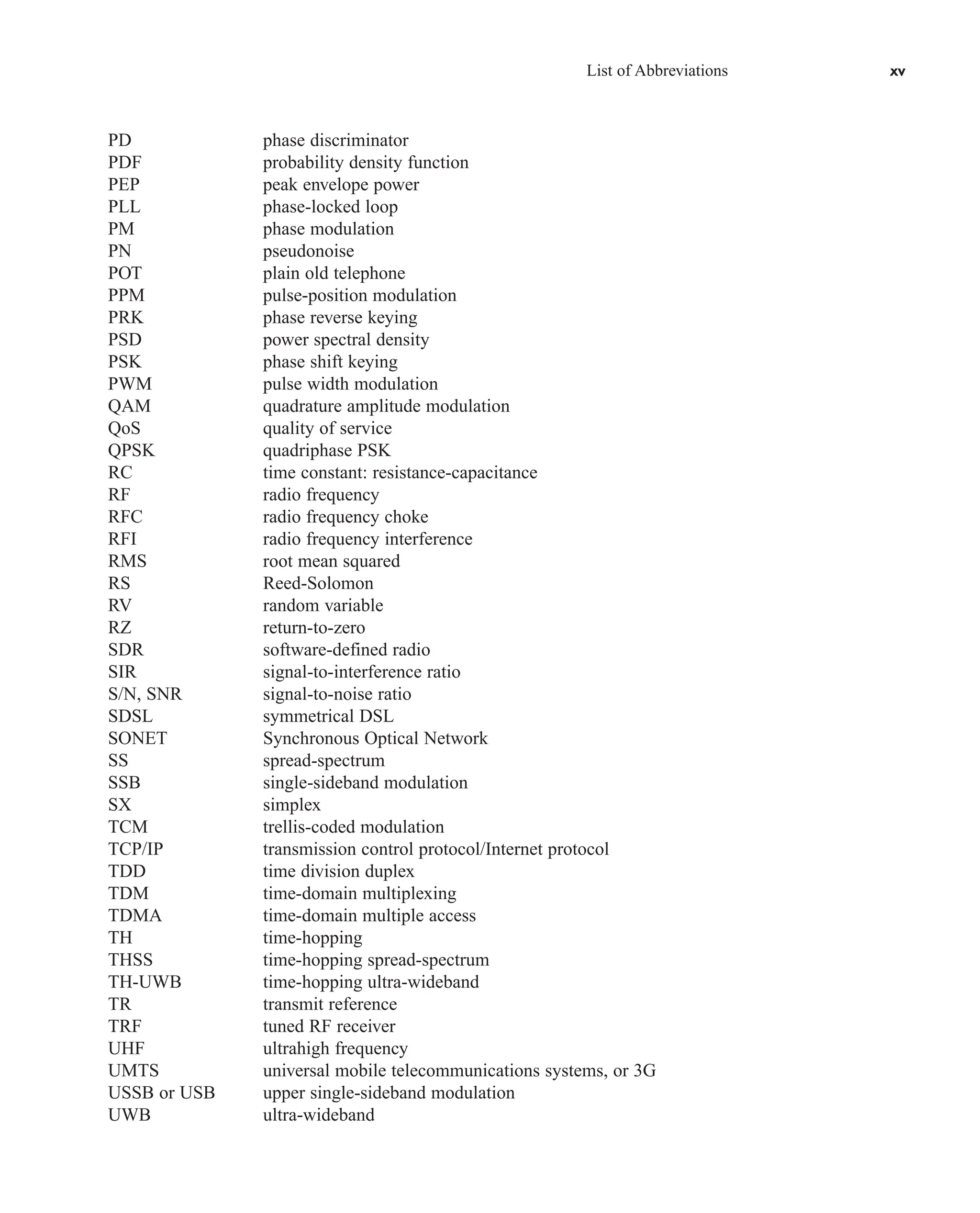

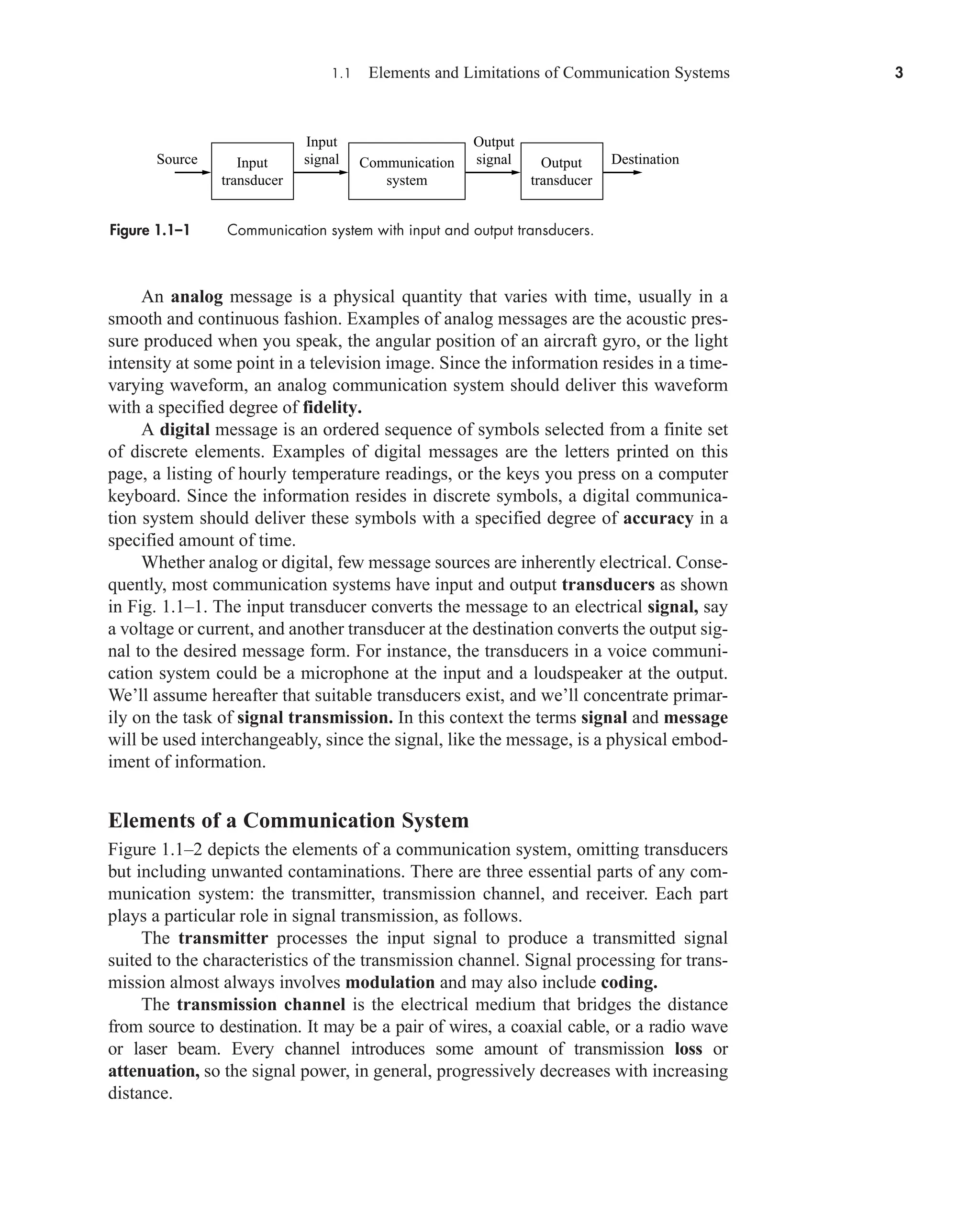

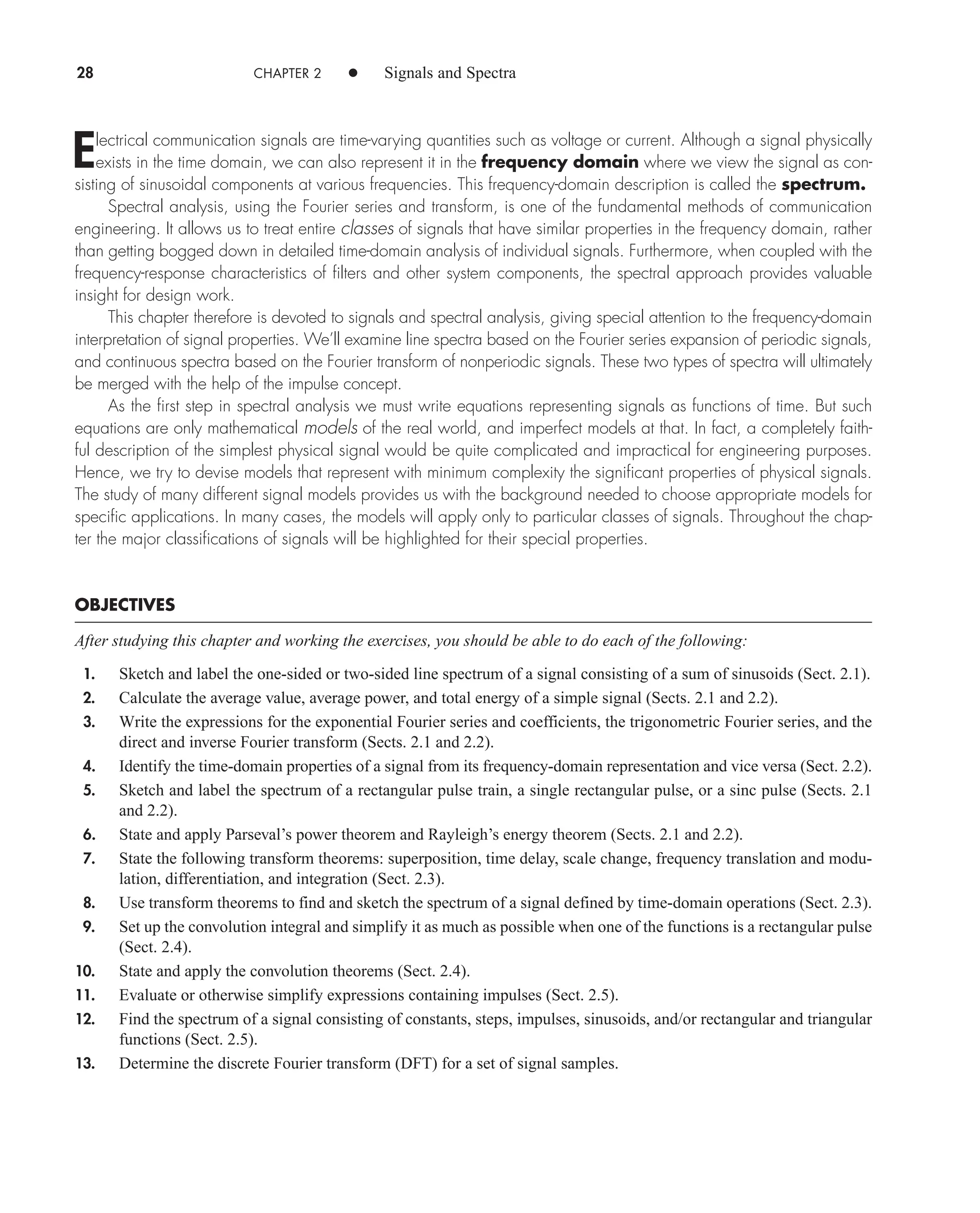

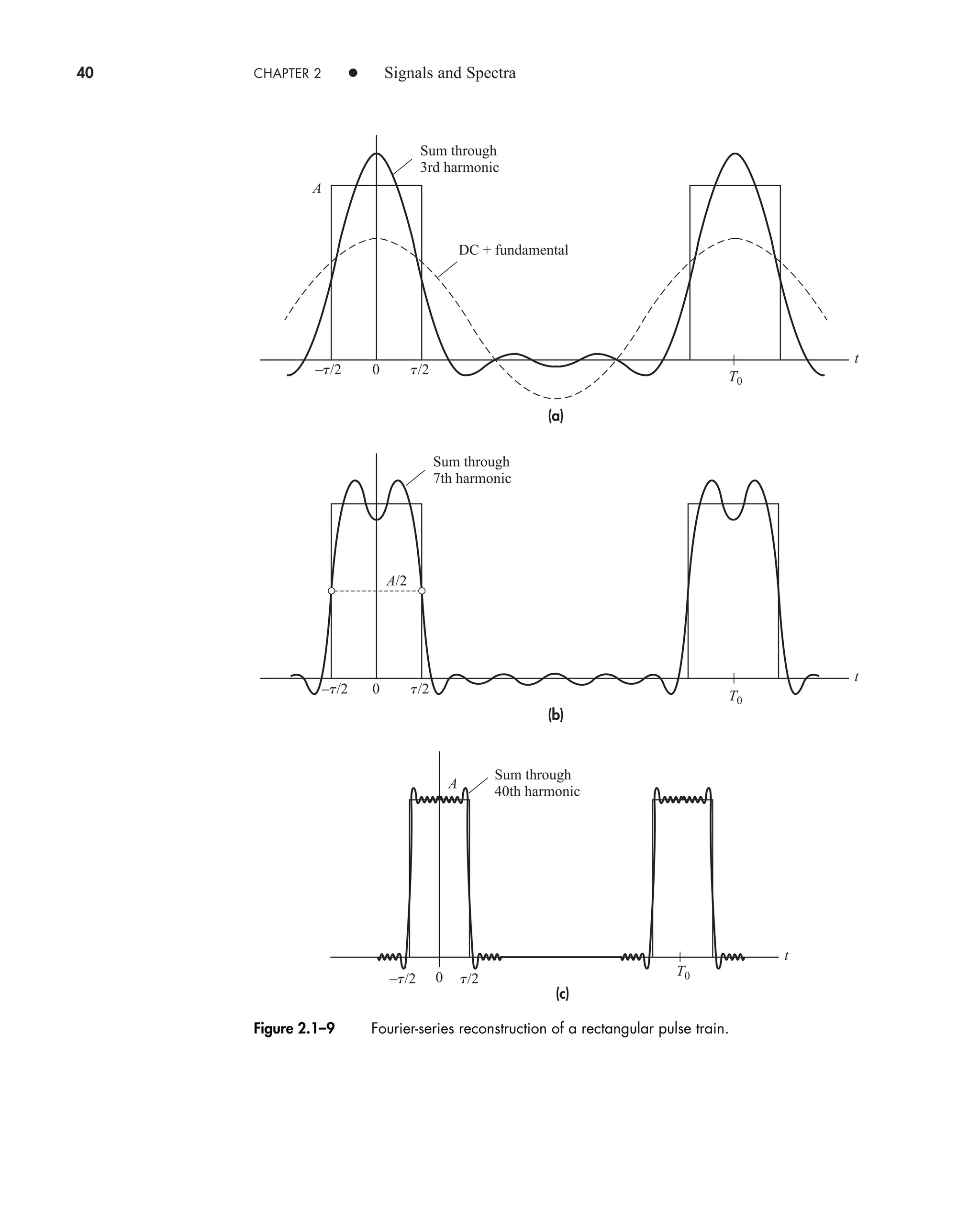

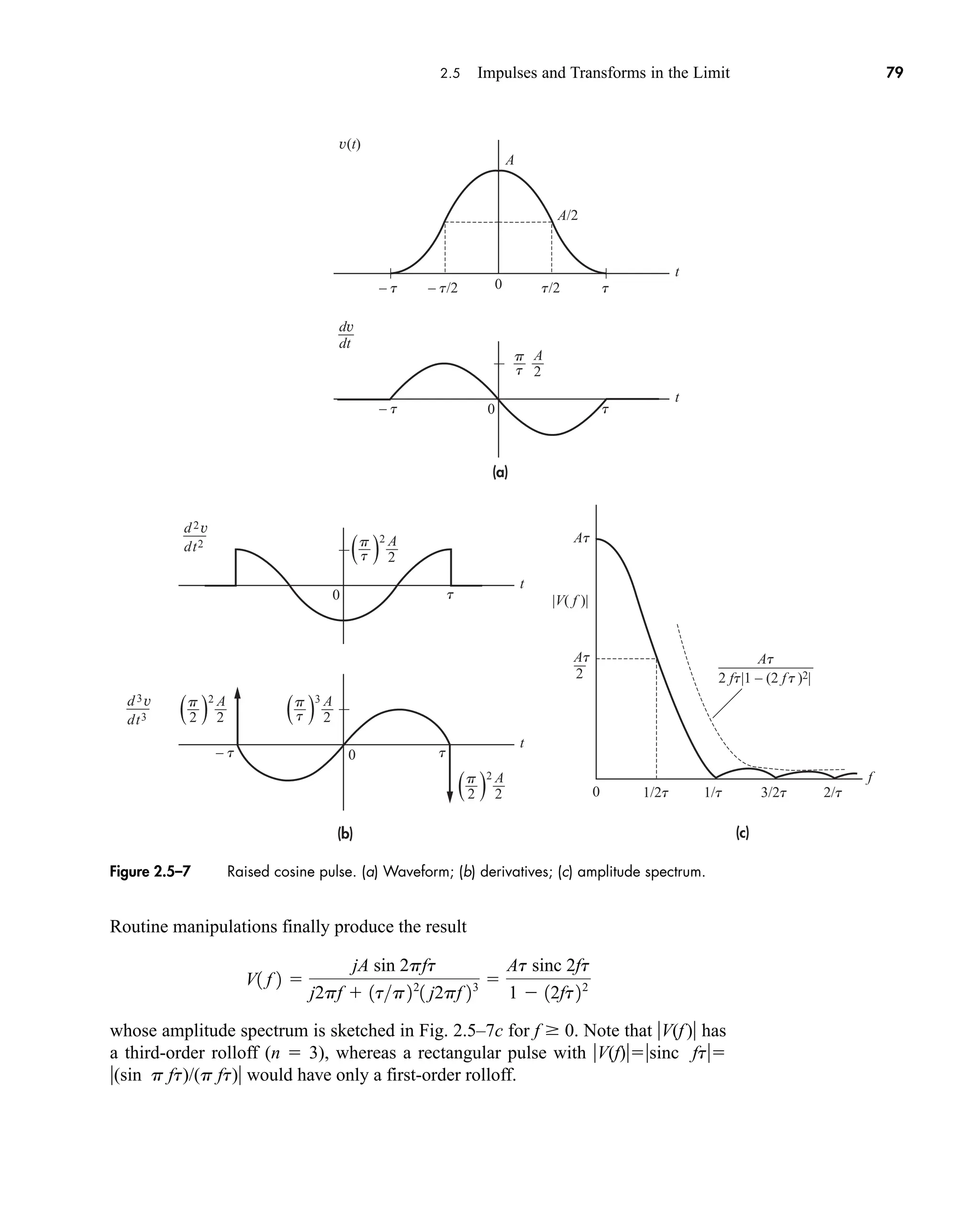

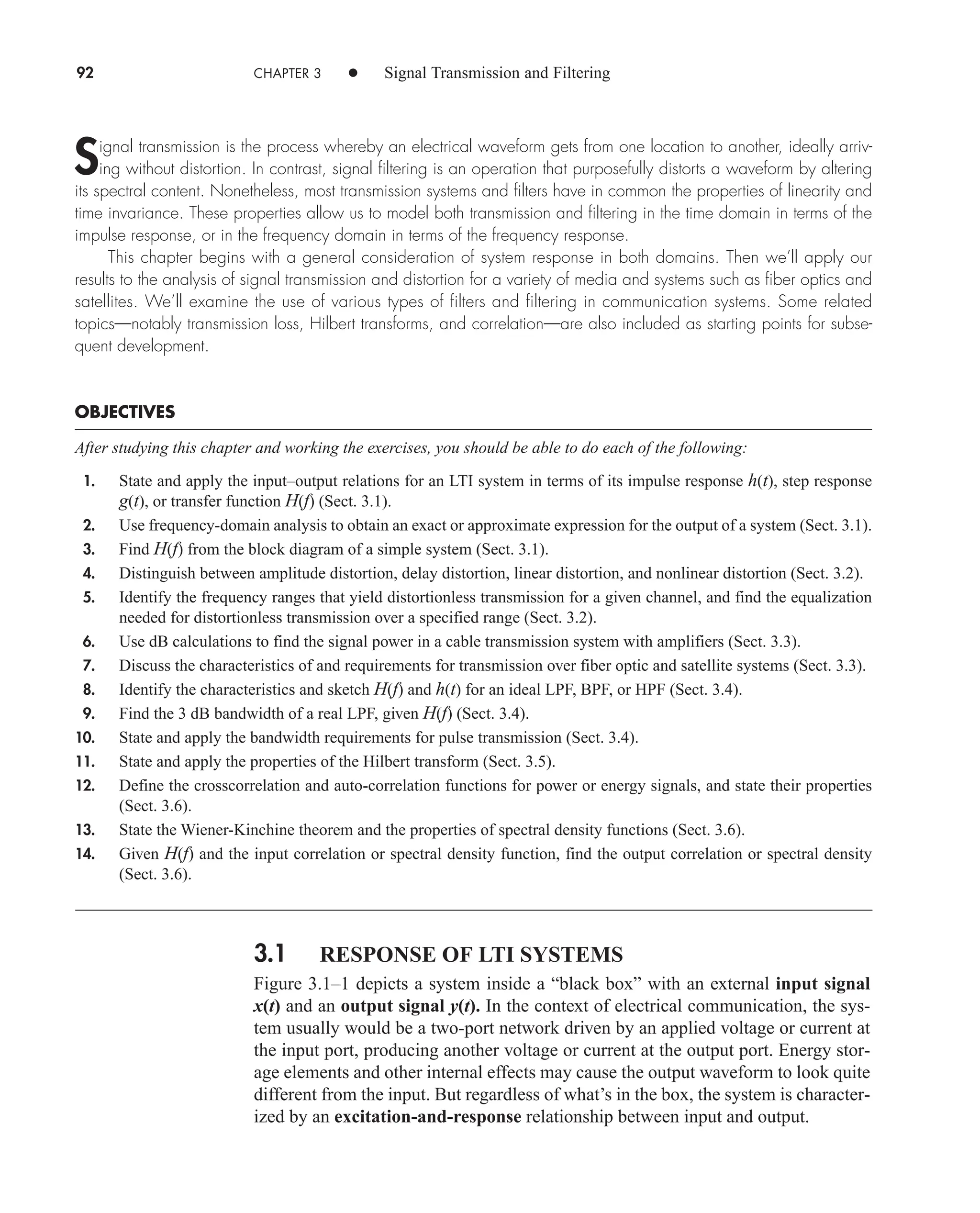

Sinc Pulse

A rather strange but important time function in communication theory is the sinc

pulse plotted in Fig. 2.2–5a and defined by

(19a)

We’ll obtain Z(f) by applying duality to the transform pair

Rewriting Eq. (19a) as

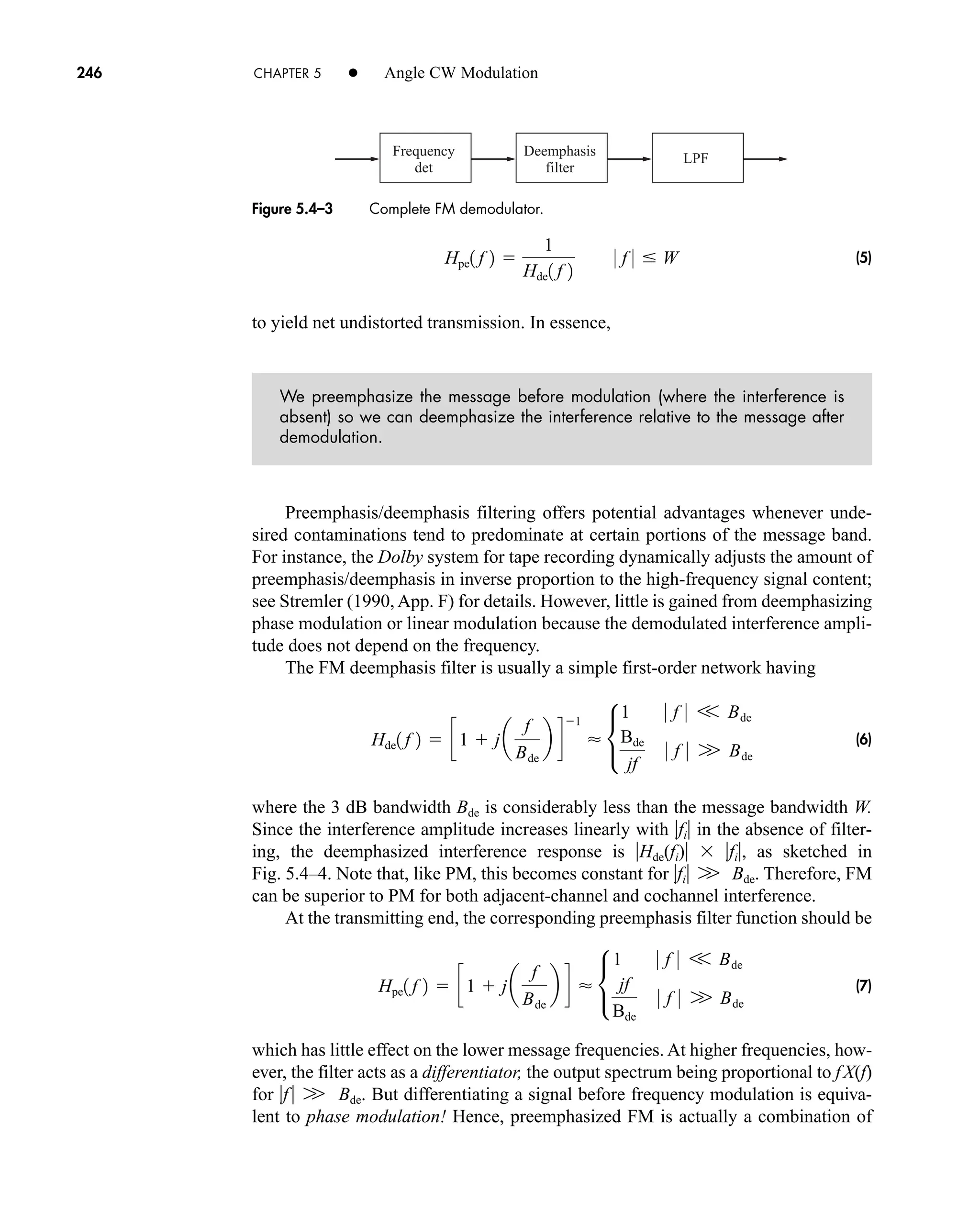

brings out the fact that z(t) V(t) with t 2W and B A/2W. Duality then says that

or

(19b)

since the rectangle function has even symmetry.

The plot of Z(f), given in Fig. 2.2–5b, shows that the spectrum of a sinc pulse

equals zero for f W. Thus, the spectrum has clearly defined width W, measured in

terms of positive frequency, and we say that Z(f ) is bandlimited. Note, however,

that the signal z(t) goes on forever and is only asymptotically timelimited.

Find the transform of z(t) B/[1 (2pt)2

] by applying duality to the result of

Exercise 2.2–1.

Z1 f 2

A

2W

ß a

f

2W

b

3z1t2 4 v1f2 Bß1ft2 1A2W2ß1f2W2

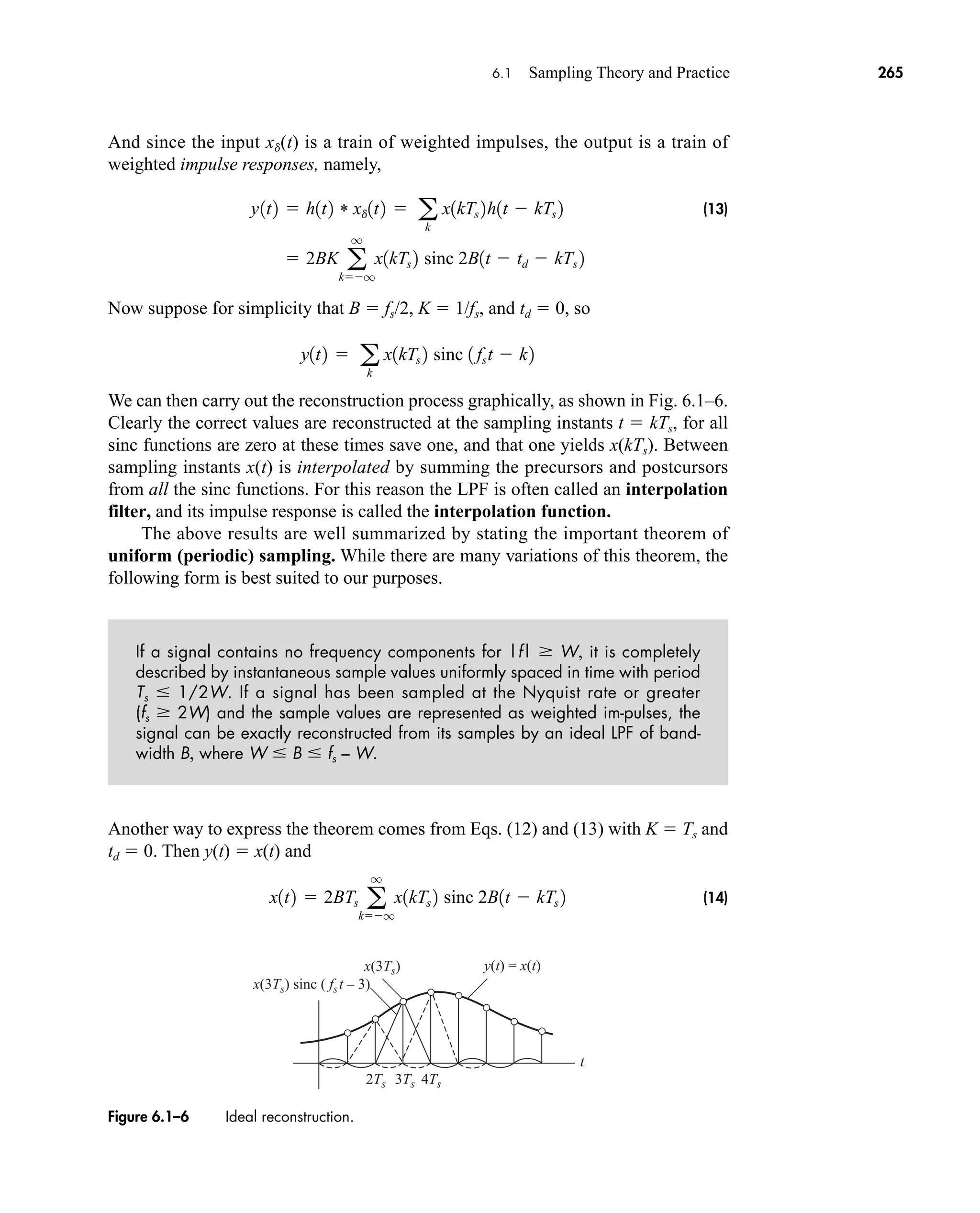

z1t2 a

A

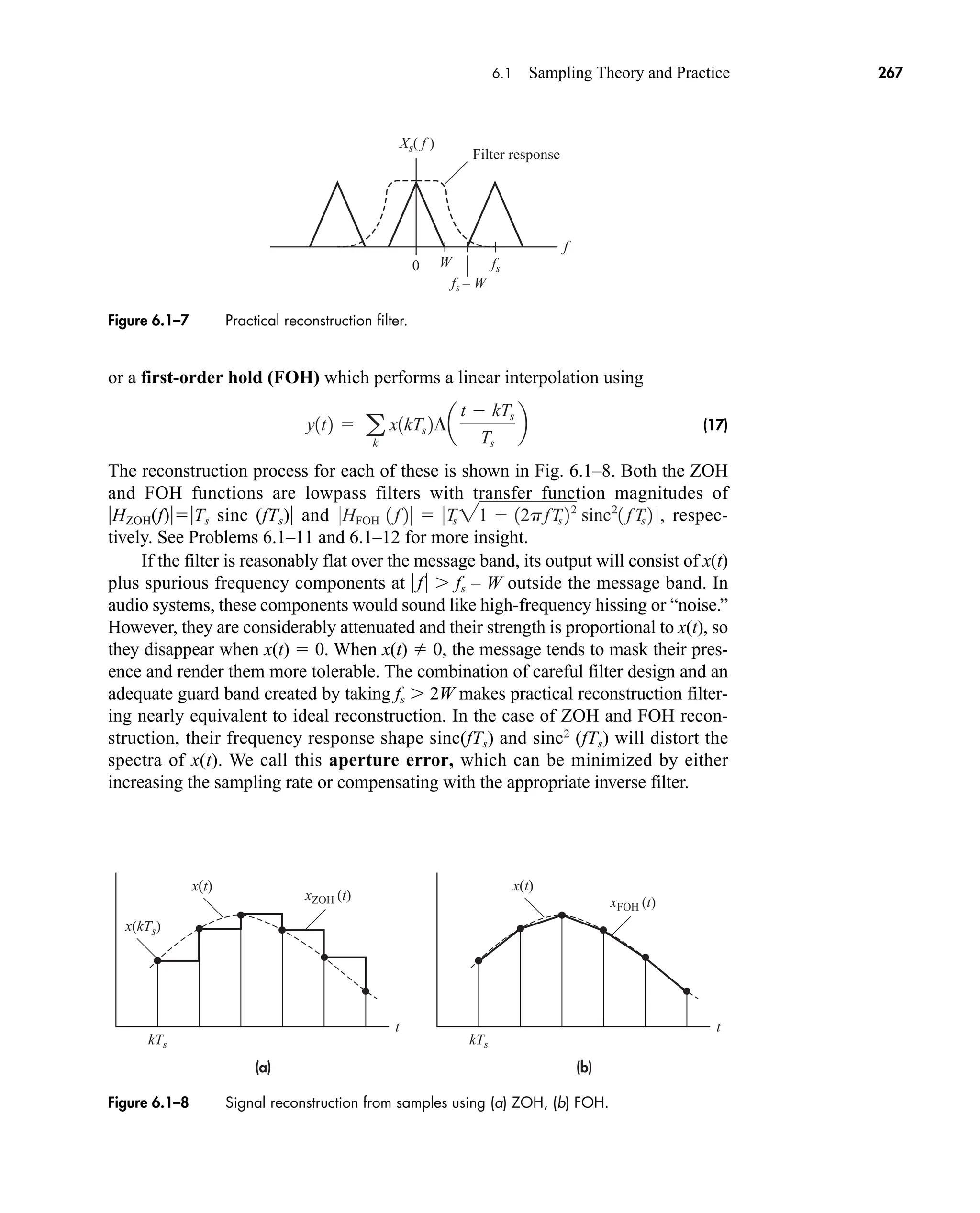

2W

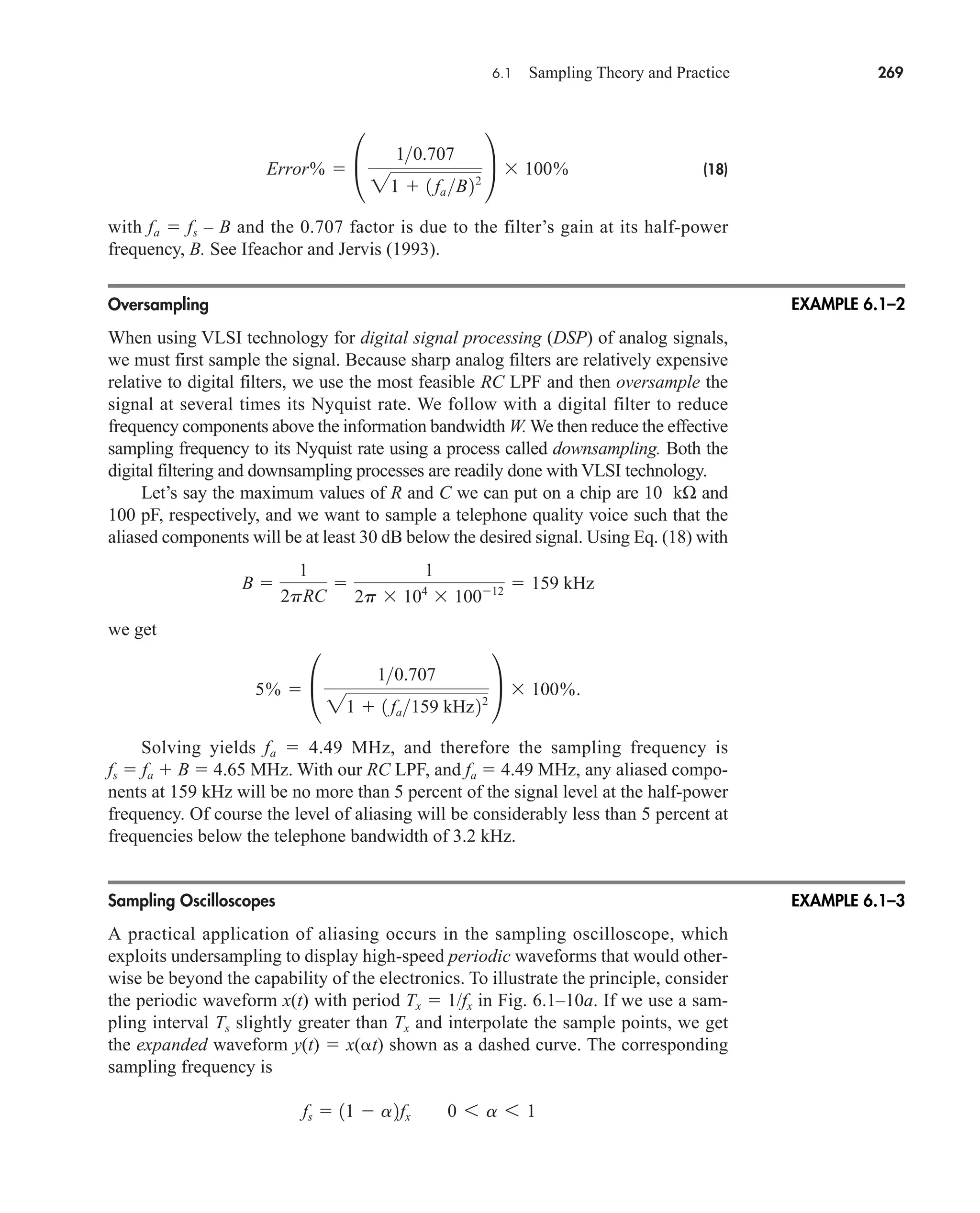

b 12W2 sinc t12W2

v1t2 Bß1tt2 V1 f 2 Bt sinc ft

z1t2 A sinc 2Wt

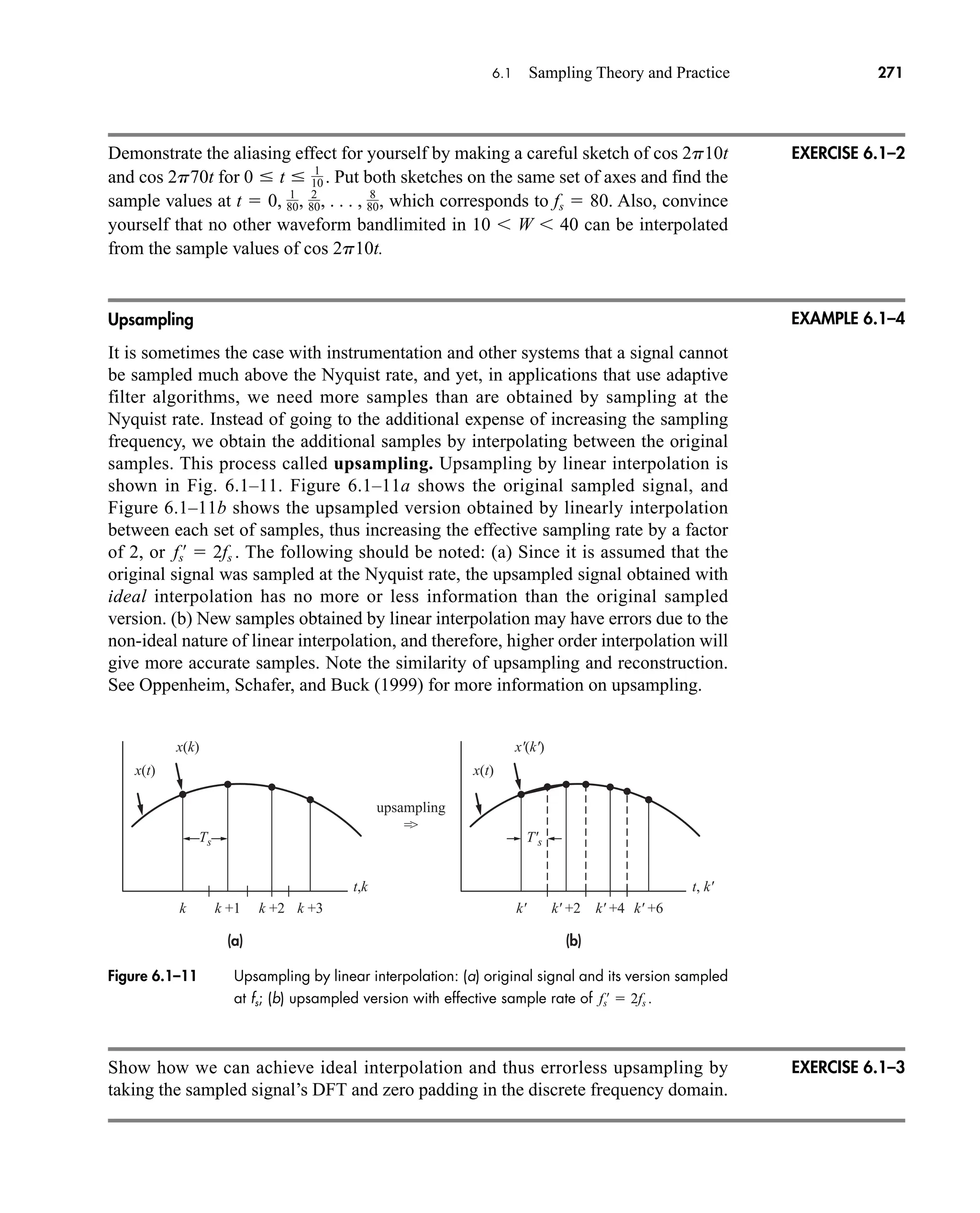

Z1f2 3z1t2 4 v1f2 v1f2.

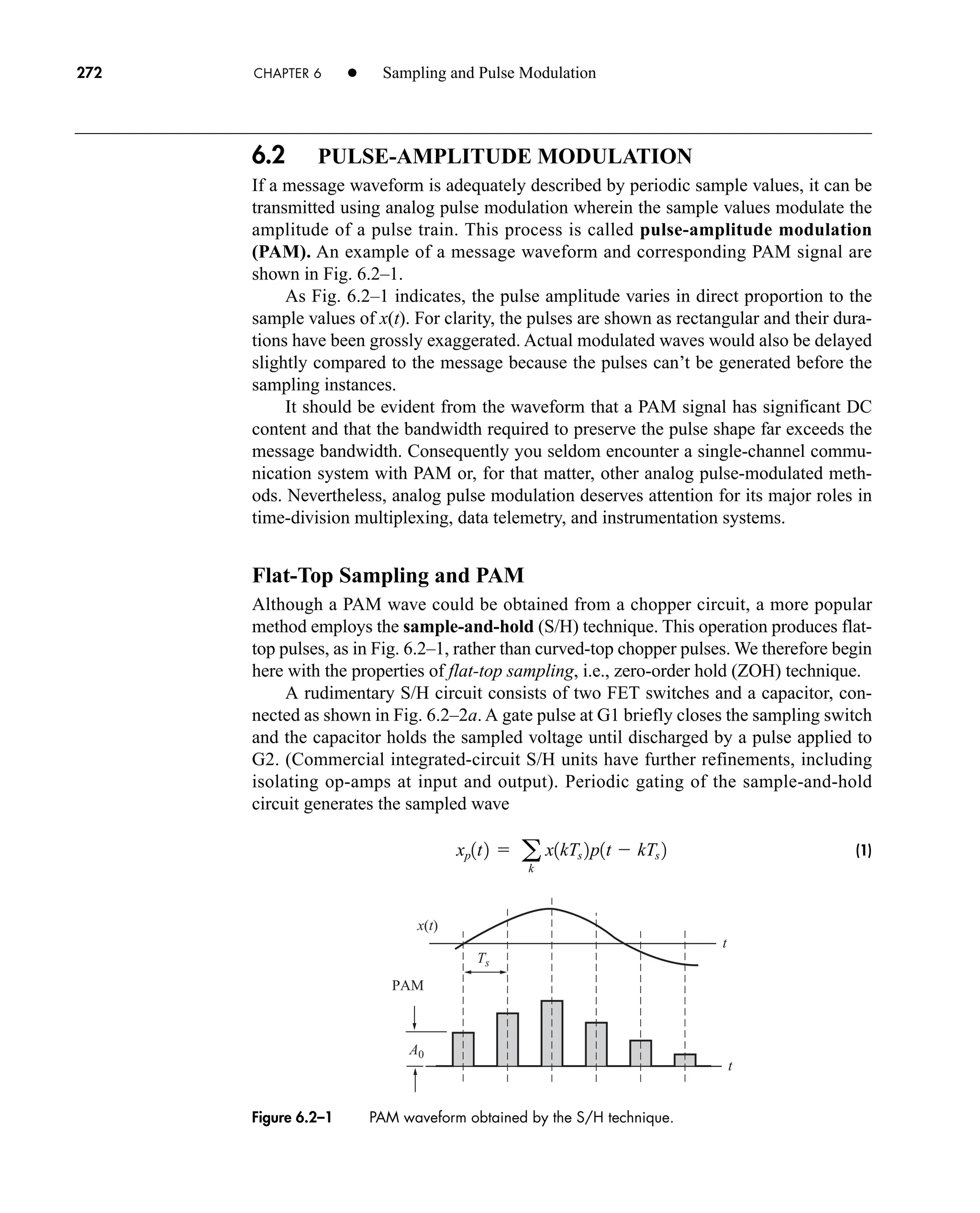

EXAMPLE 2.2–3

Figure 2.2–5 A sinc pulse and its bandlimited spectrum.

EXERCISE 2.2–3

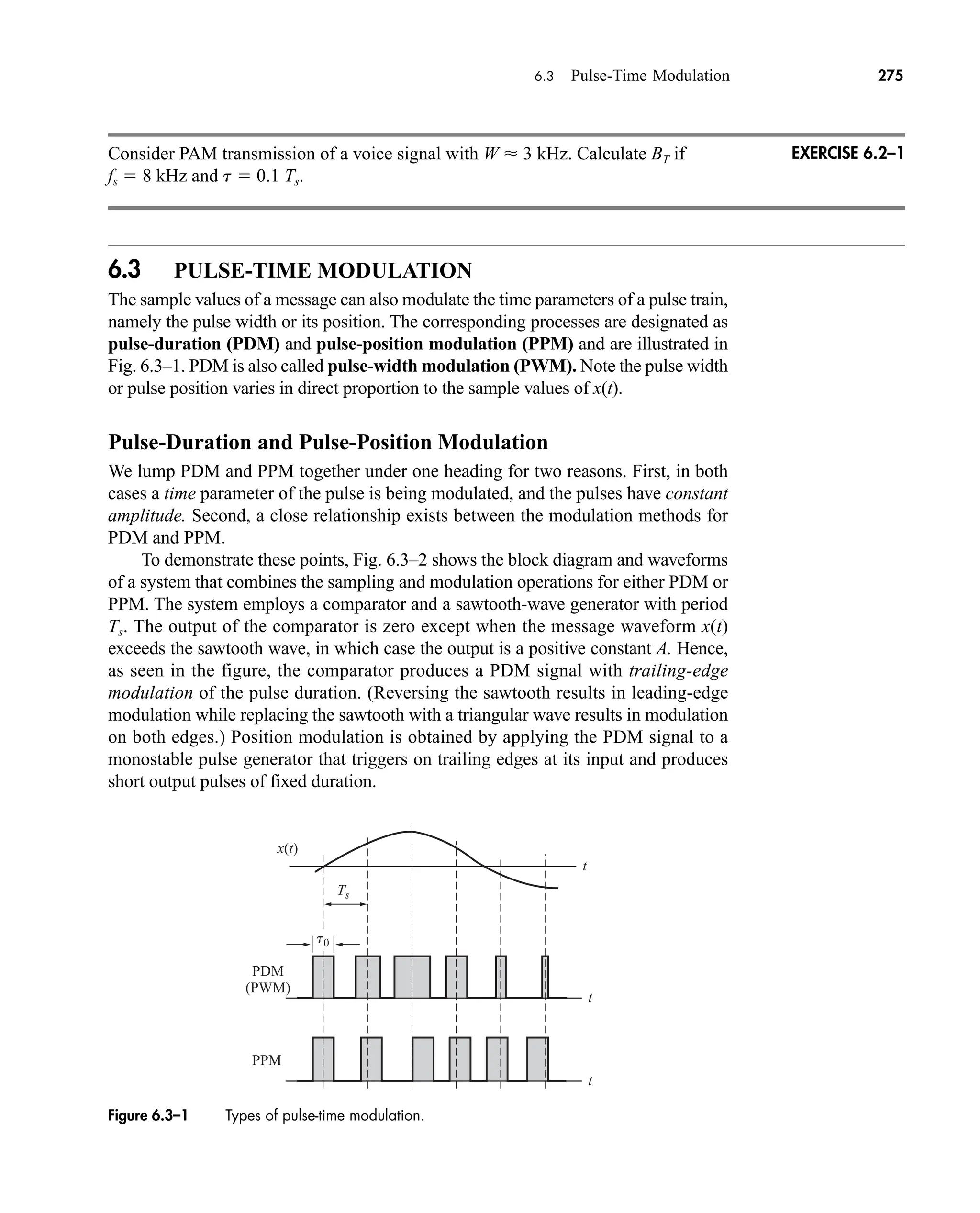

0 0

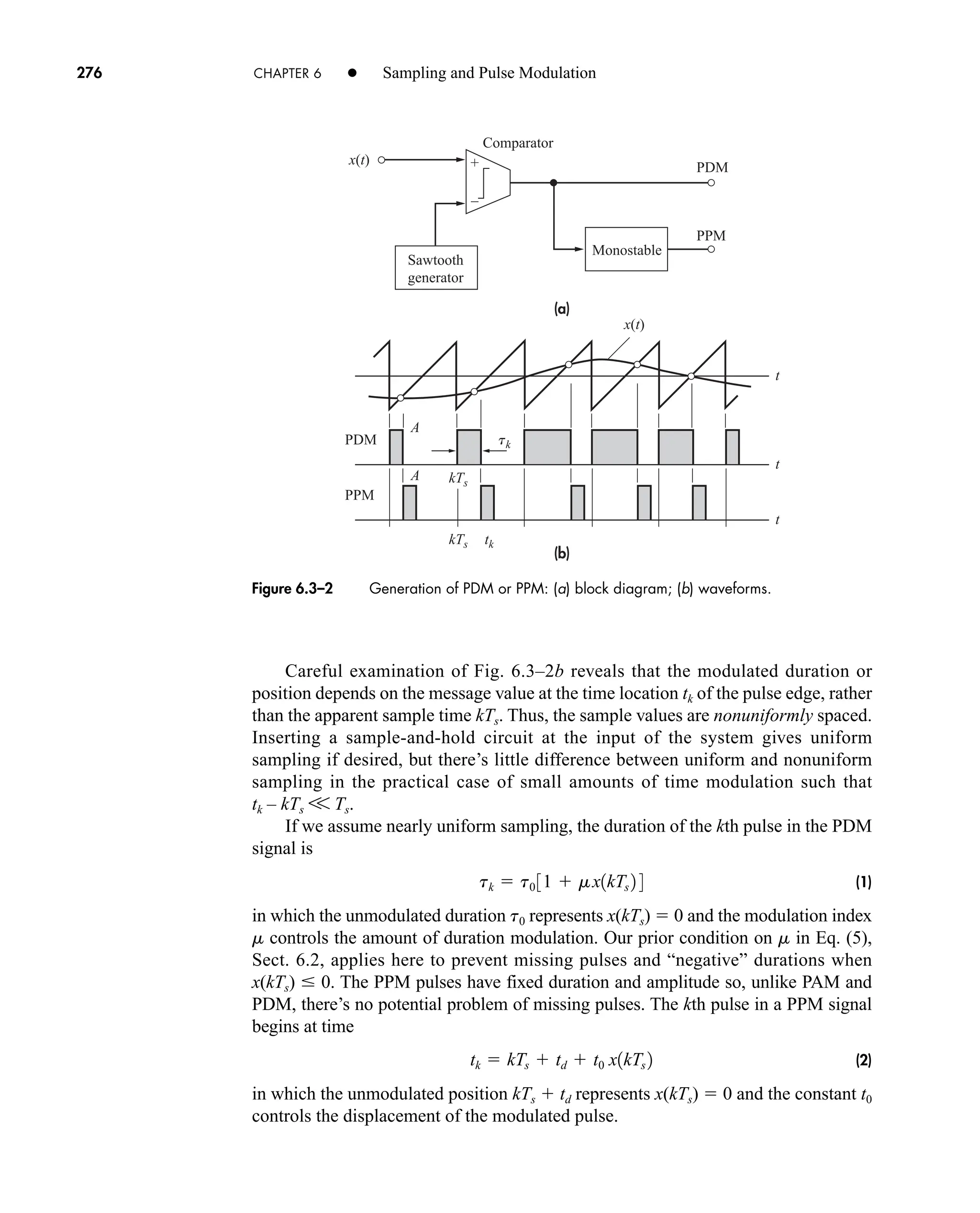

f f

W

–W

z(t)

A

Z( f )

–1/2W

A/2W

1/2W

(b)

(a)

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:03 PM Page 53](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-75-2048.jpg)

![54 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

Transform Calculations

Except in the case of a very simple waveform, brute-force integration should be

viewed as the method of last resort for transform calculations. Other, more practical

methods are discussed here.

When the signal in question is defined mathematically, you should first consult

a table of Fourier transforms to see if the calculation has been done before. Both

columns of the table may be useful, in view of the duality theorem. A table of

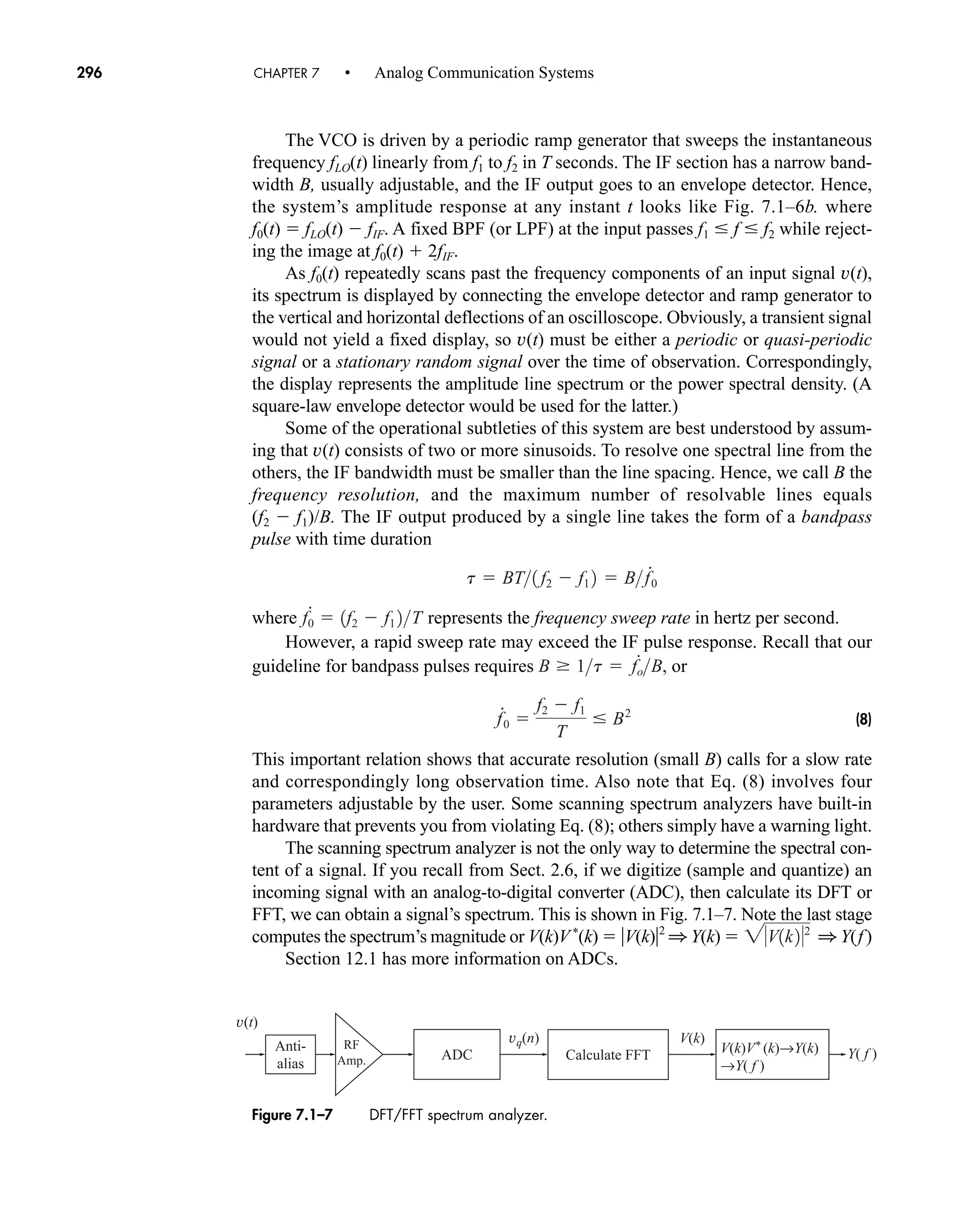

Laplace transforms also has some value, as mentioned in conjunction with Eq. (14).

Besides duality, there are several additional transform theorems covered in

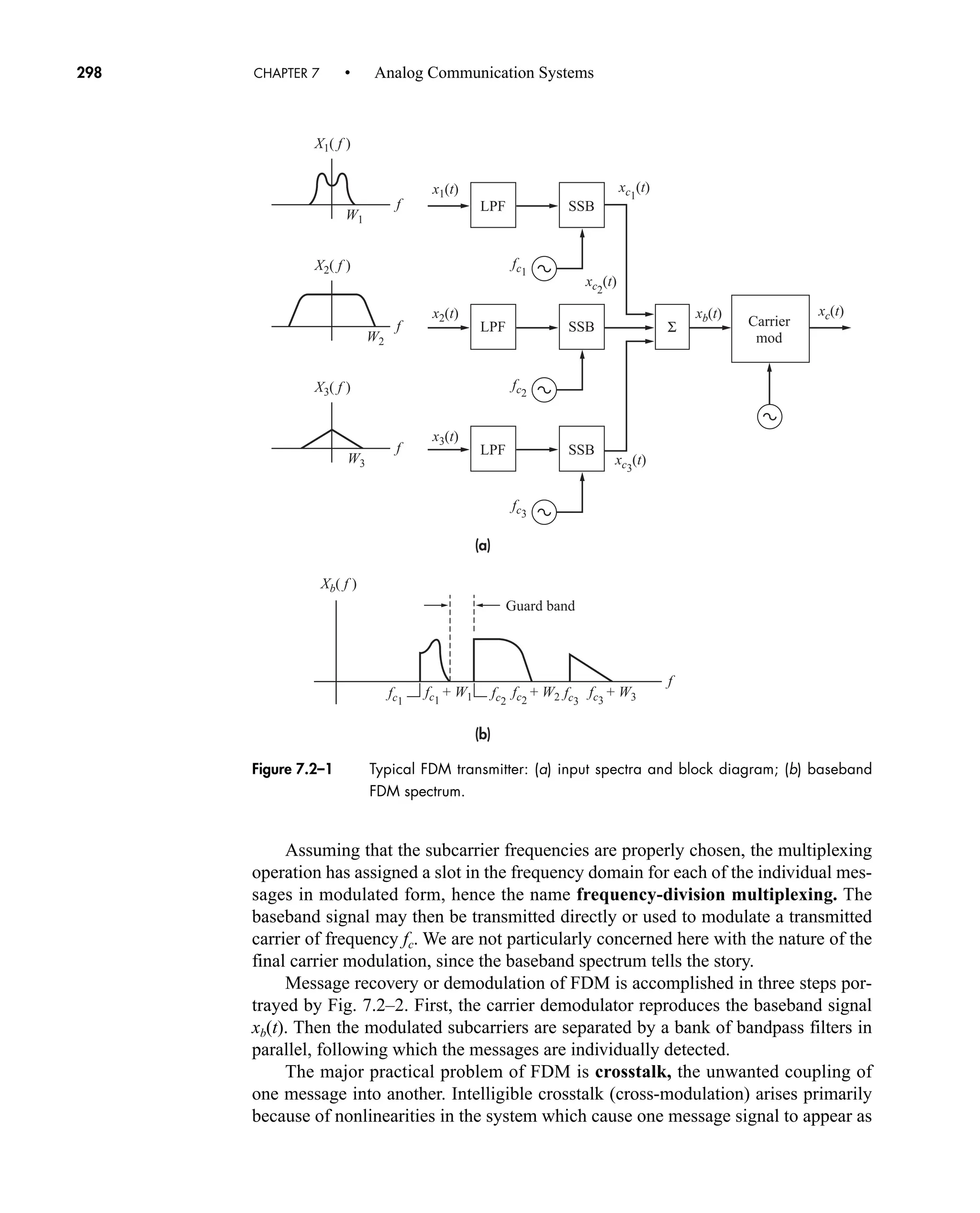

Sect. 2.3. These theorems often help you decompose a complicated waveform into

simpler parts whose transforms are known. Along this same line, you may find it

expedient to approximate a waveform in terms of idealized signal models. Suppose

z̃(t) approximates z(t) and magnitude-squared error z(t) z̃(t)2

is a small quantity. If

Z(f) [z(t)] and

~

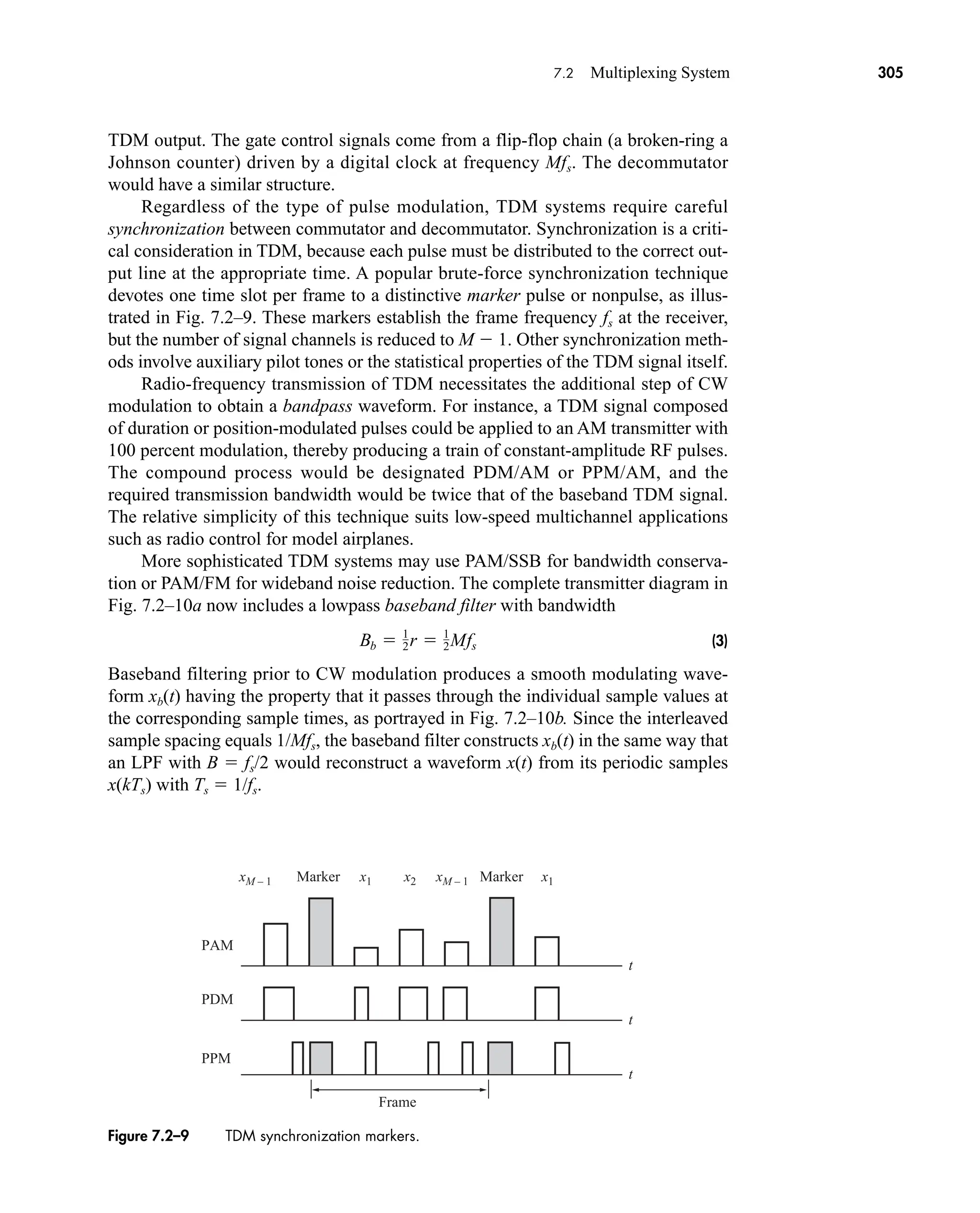

Z(f ) [z̃(t)] then

(20)

which follows from Rayleigh’s theorem with v(t) z(t) z̃(t). Thus, the integrated

approximation error has the same value in the time and frequency domains.

The above methods are easily modified for the calculation of Fourier series

coefficients. Specifically, let v(t) be a periodic signal and let z(t) v(t)Π (t/T0), a

nonperiodic signal consisting of one period of v(t). If you can obtain

(21a)

then, from Eq. (14), Sect. 2.1, the coefficients of v(t) are given by

(21b)

This relationship facilitates the application of transform theorems to Fourier series

calculations.

Finally, if the signal is expressed in numerical form as a set of samples, its trans-

form, as we will see in Sect. 2.6, can be found via numerical calculations. For this

purpose the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) and its faster version, the Fast Fourier

Transform is used.

2.3 TIME AND FREQUENCY RELATIONS

Rayleigh’s theorem and the duality theorem in the previous section helped us draw

useful conclusions about the frequency-domain representation of energy signals.

Now we’ll look at some of the many other theorems associated with Fourier trans-

forms. They are included not just as manipulation exercises but for two very practical

reasons. First, the theorems are invaluable when interpreting spectra, for they express

cn

1

T0

Z1nf0 2

Z1 f 2 3v1t2ß1tT0 2 4

q

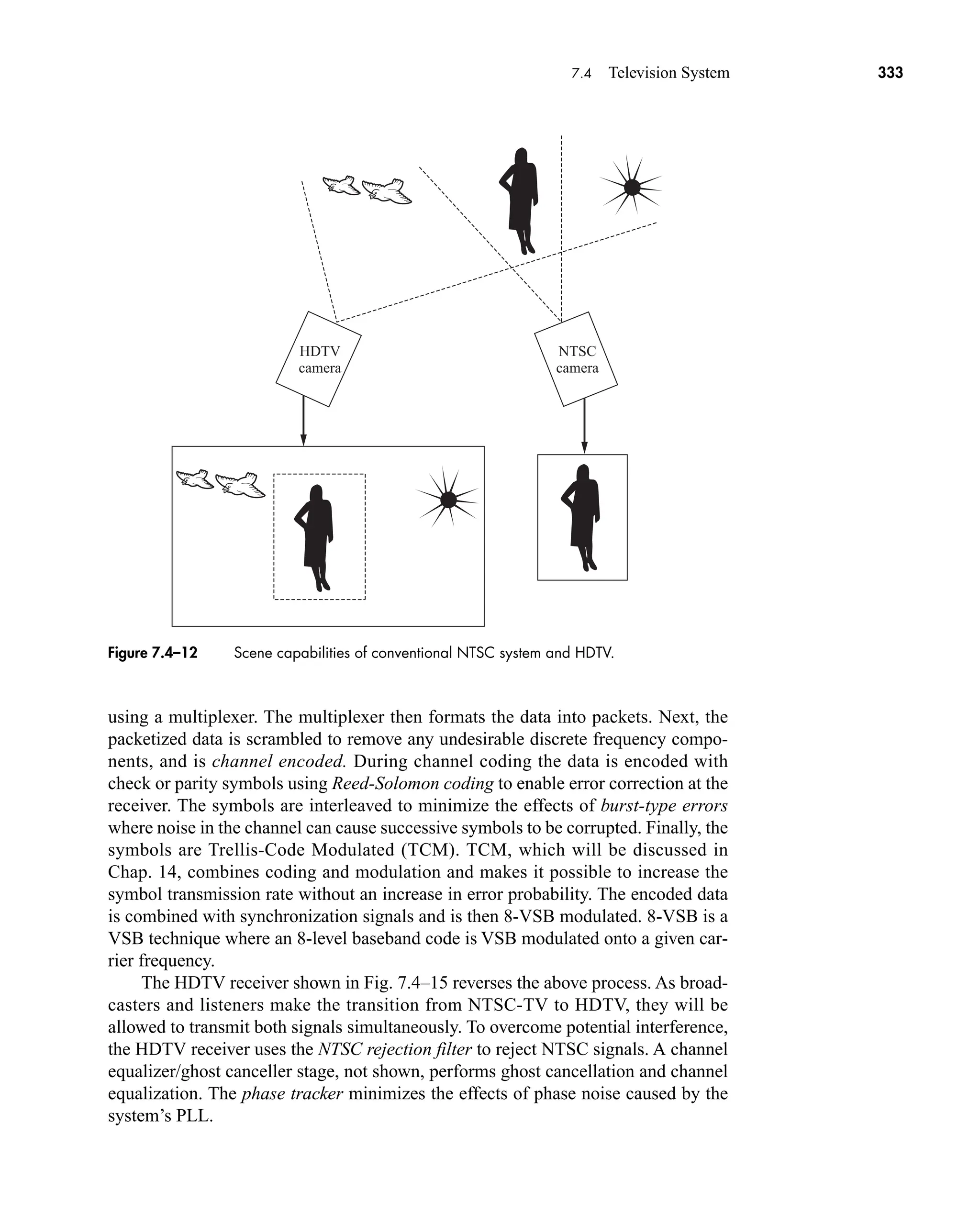

q

0 Z1 f 2 Z

1 f 2 02

df

q

q

0z1t2 z

1t2 02

dt

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/15/08 9:29 PM Page 54](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-76-2048.jpg)

![2.4 Convolution 63

Convolution Integral

The convolution of two functions of the same variable, say y(t) and w(t), is defined by

(1)

The notation y(t) * w(t) merely stands for the operation on the right-hand side of

Eq. (1) and the asterisk (*) has nothing to do with complex conjugation. Equation (1)

is the convolution integral, often denoted y * w when the independent variable is

unambiguous. At other times the notation [y(t)] * [w(t)] is necessary for clarity. Note

carefully that the independent variable here is t, the same as the independent variable

of the functions being convolved; the integration is always performed with respect to a

dummy variable (such as ), and t is a constant insofar as the integration is concerned.

Calculating y(t) * w(t) is no more difficult than ordinary integration when the

two functions are continuous for all t. Often, however, one or both of the functions is

defined in a piecewise fashion, and the graphical interpretation of convolution

becomes especially helpful.

By way of illustration, take the functions in Fig. 2.4–1a where

For the integrand in Eq. (1), y( ) has the same shape as y(t) and

But obtaining the picture of w(t ) as a function of requires two steps: First, we

reverse w(t) in time and replace t with to get w( ); second, we shift w( ) to the

right by t units to get w[( t)] w(t ) for a given value of t. Fig. 2.4–1b

shows y( ) and w(t ) with t 0. The value of t always equals the distance from

the origin of y( ) to the shifted origin of w( ) indicated by the dashed line.

As y(t) * w(t) is evaluated for q t q, w(t ) slides from left to right

with respect to y( ), so the convolution integrand changes with t. Specifically, we

see in Fig. 2.4–1b that the functions don’t overlap when t 0; hence, the integrand

equals zero and

When 0 t T as in Fig. 2.4–1c, the functions overlap for 0 t, so t

becomes the upper limit of integration and

A

T

1t 1 et

2 0 6 t 6 T

v1t2 * w1t2

t

0

Ael

a

t l

T

b dl

v1t2 * w1t2 0 t 6 0

w1t l2

t l

T

0 6 t l 6 T

w1t2 tT 0 6 t 6 T

v1t2 Aet

0 6 t 6 q

v1t2 * w1t2

^

q

q

v1l2w1t l2 dl

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:03 PM Page 63](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-85-2048.jpg)

![2.5 Impulses and Transforms in the Limit 77

It’s a simple matter to confirm the direct transform relationship [Ad(t td)]

consistency therefore requires that A d(t td), which

leads to a significant integral expression for the unit impulse. Specifically, since

we conclude that

(23)

Thus, the integral on the left side may be evaluated in the limiting form of the unit

impulse—a result we’ll put immediately to work in a proof of the Fourier integral

theorem.

Let y(t) be a continuous time function with a well-defined transform

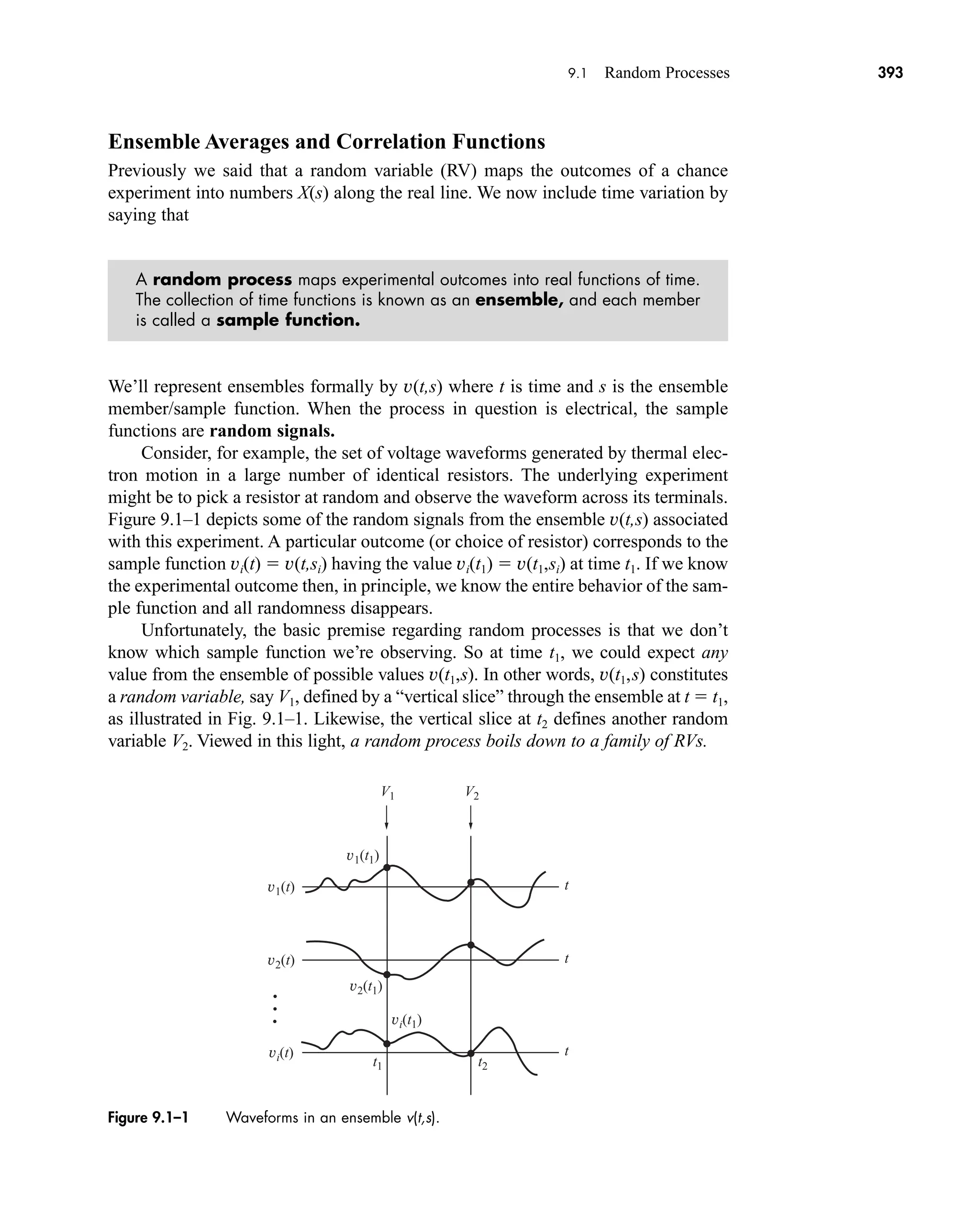

Our task is to show that the inverse transform does, indeed, equal

y(t). From the definitions of the direct and inverse transforms we can write

But the bracketed integral equals (t ), from Eq. (23), so

(24)

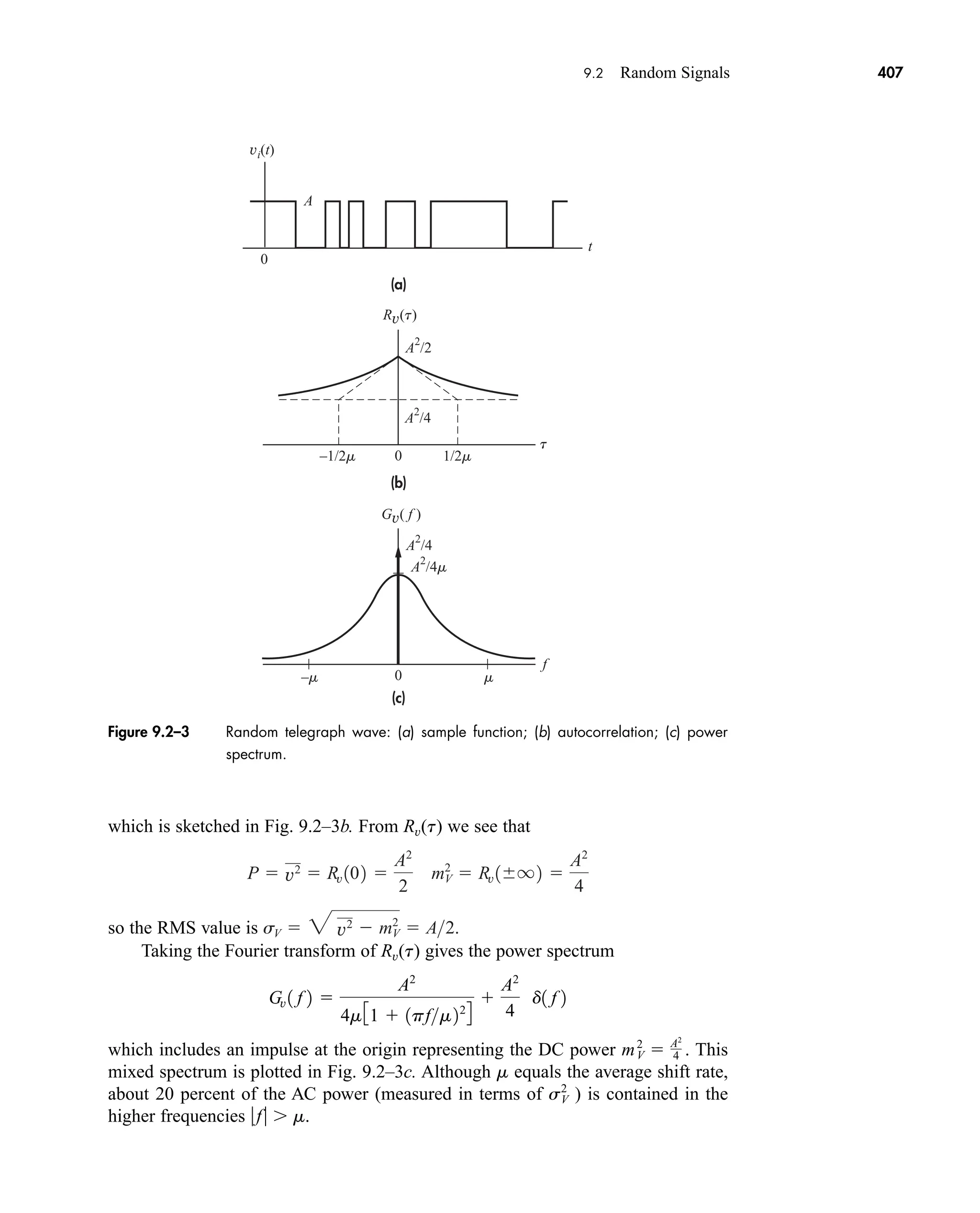

Therefore equals y(t), in the same sense that y(t) * (t) y(t). A more

rigorous proof, including Gibbs’s phenomena at points of discontinuity, is given by

Papoulis (1962, Chap. 2).

Lastly, we relate the unit impulse to the unit step by means of the integral

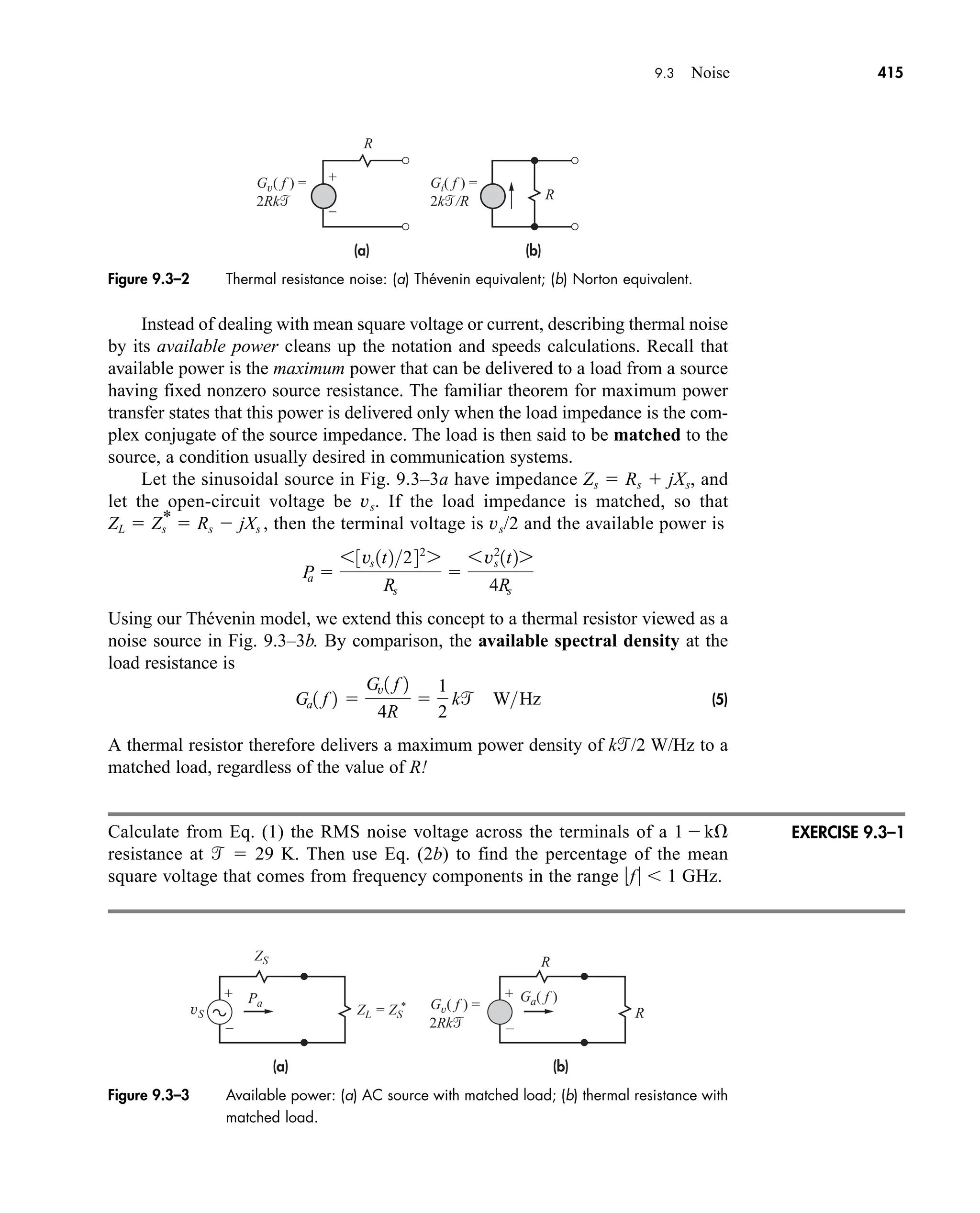

(25)

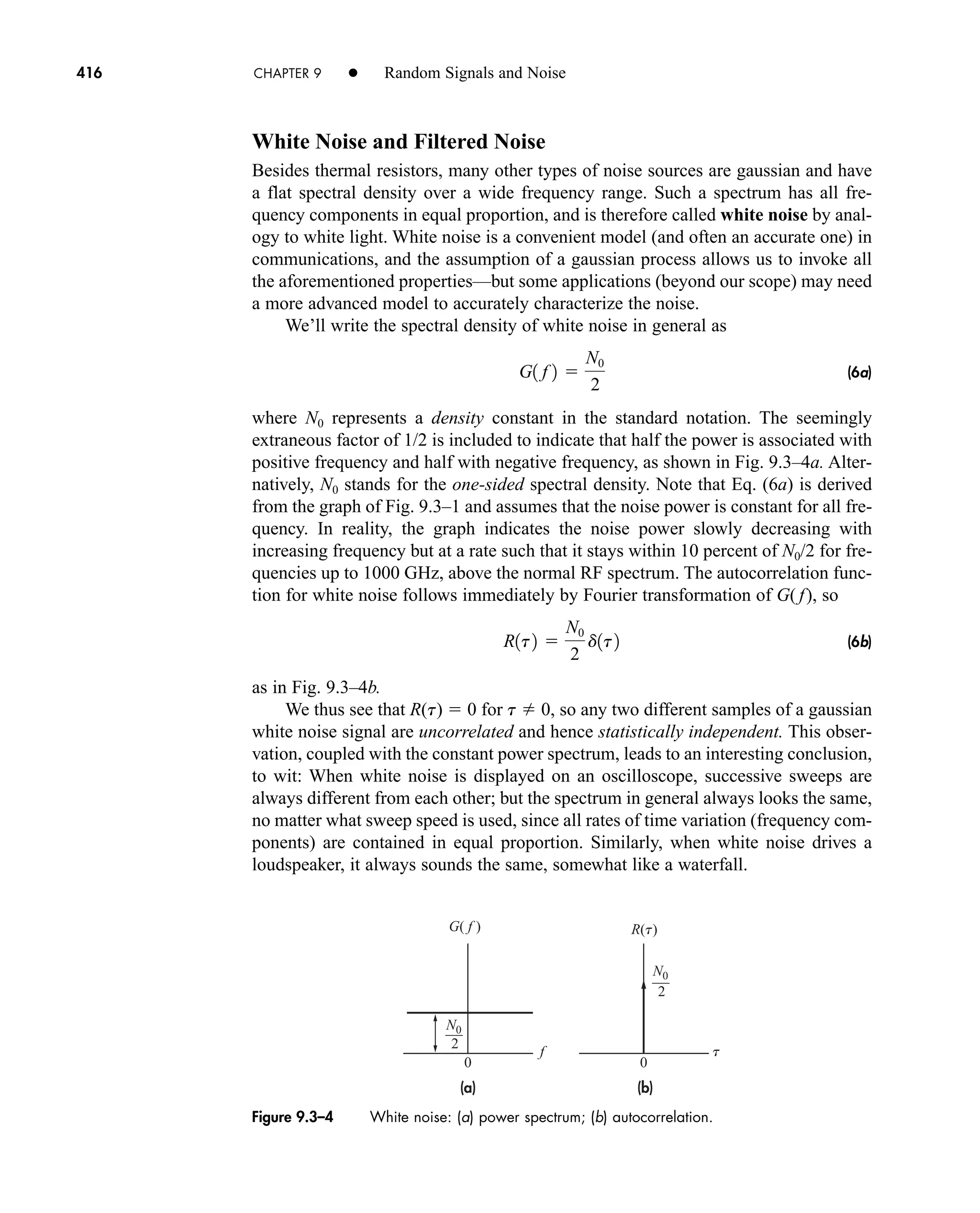

Differentiating both sides then yields

(26)

which provides another interpretation of the impulse in terms of the derivative of a

step discontinuity.

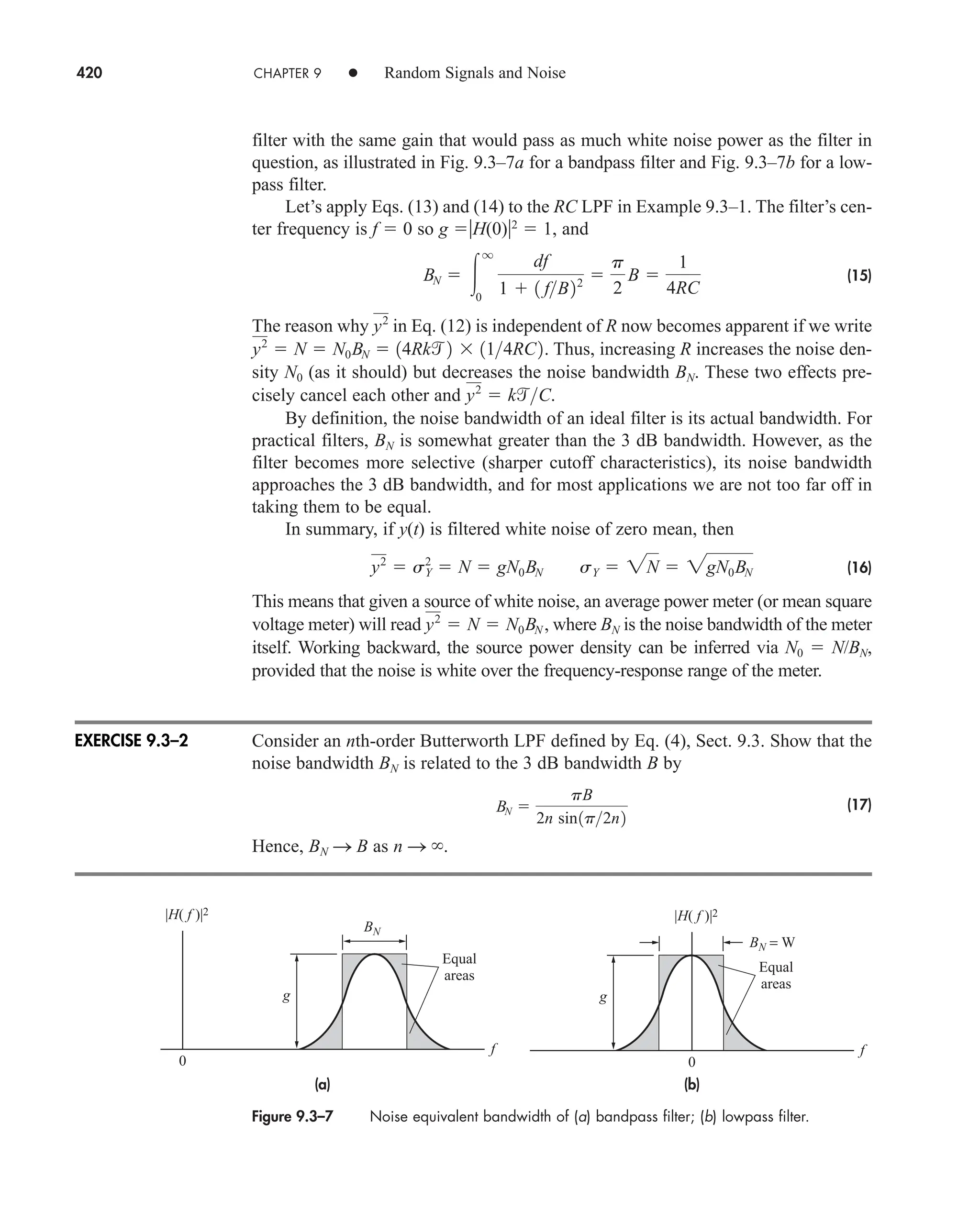

Equations (26) and (22), coupled with the differentiation theorem, expedite cer-

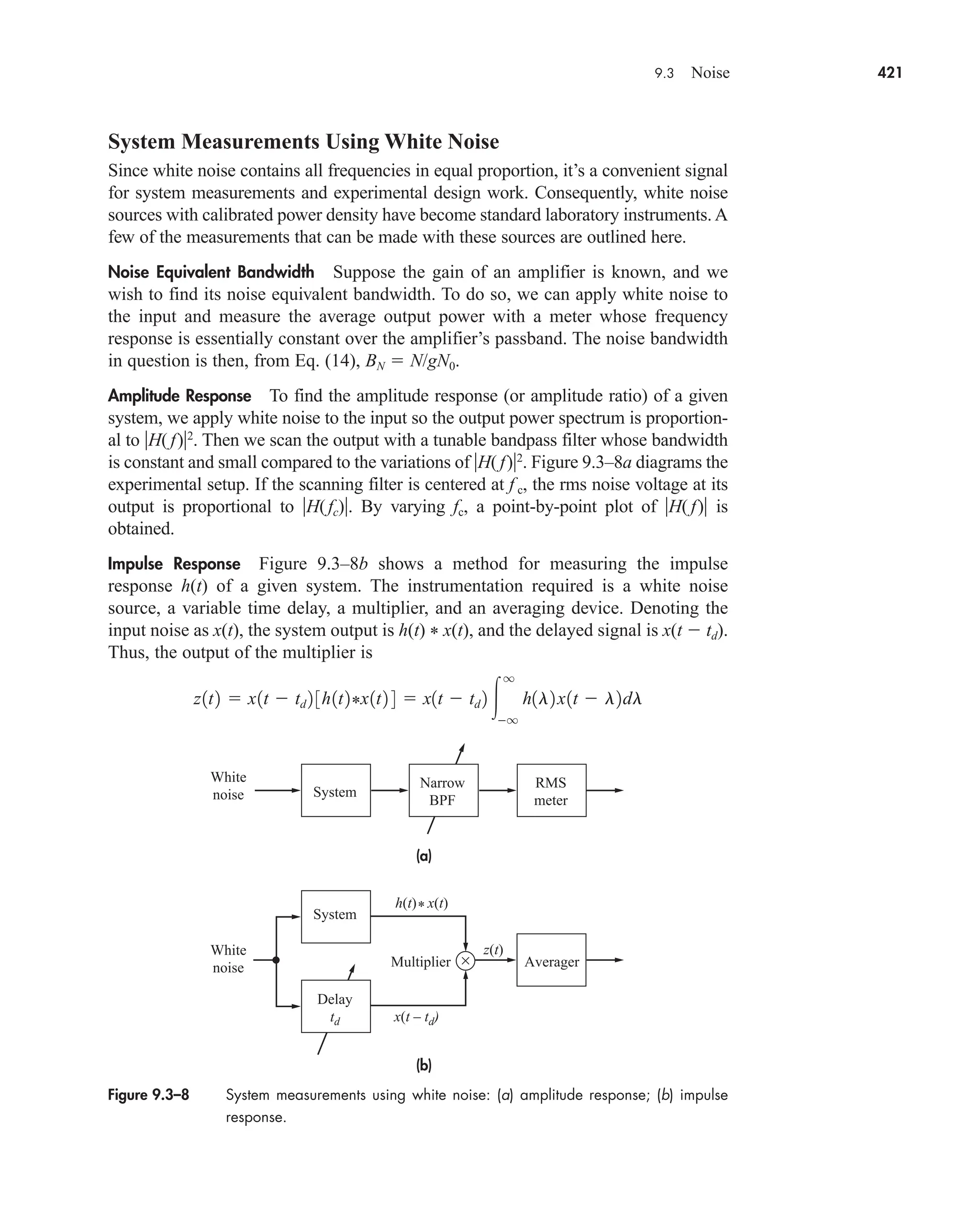

tain transform calculations and help us predict a signal’s high-frequency spectral

d1t td 2

d

dt

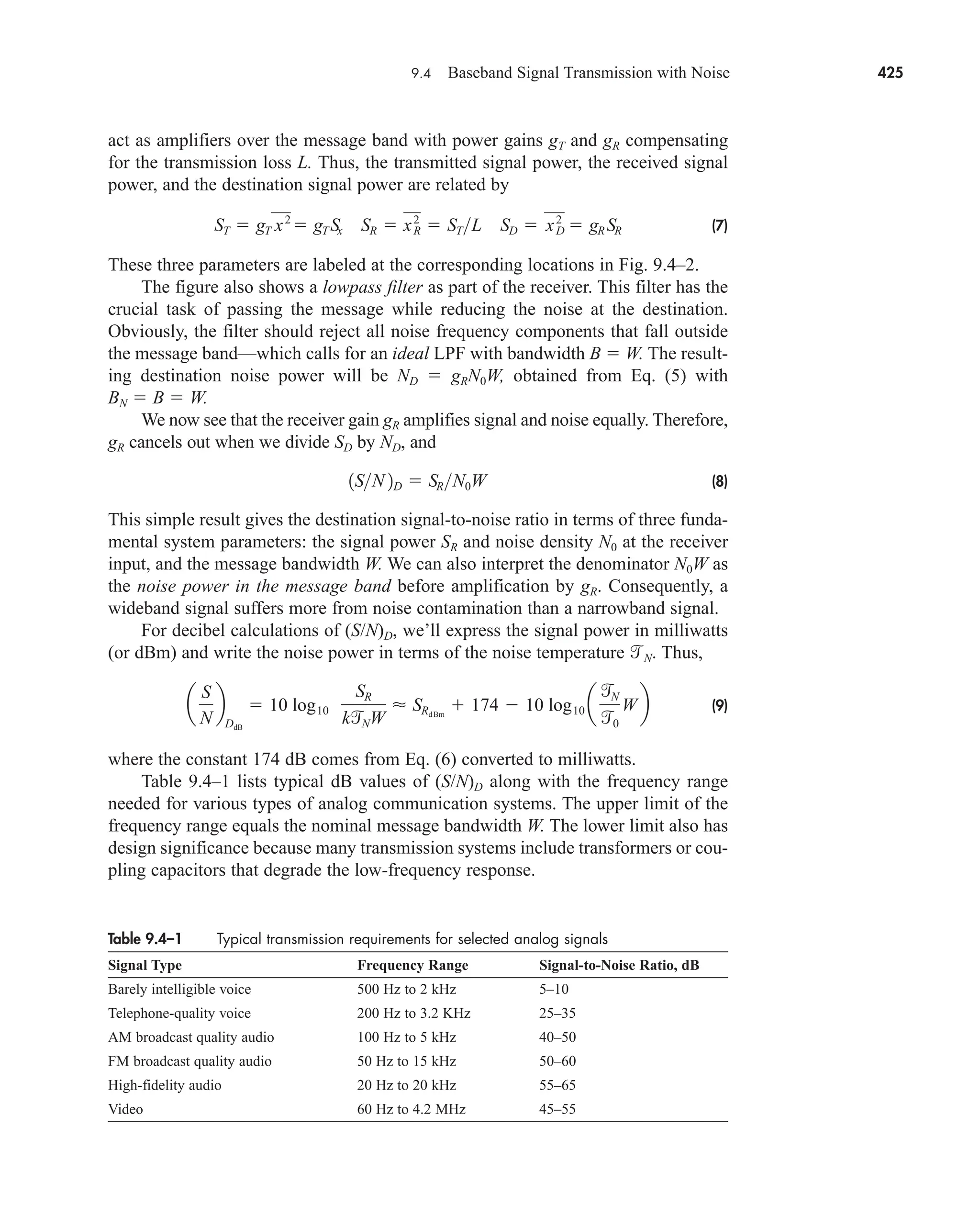

u1t td 2

u1t td 2

t

q

d1l td 2 dl e

1 t 7 td

0 t 6 td

1

3V1f2 4

1

3V1 f 2 4

q

q

v1l2 d1t l2 dl v1t2 * d1t2

q

q

v1l2 c

q

q

ej2p1tl2 f

df d dl

1

3V1 f 2 4

q

q

c

q

q

v1l2ej2pfl

dldej2pft

df

V1f2 3v1t2 4.

q

q

ej2pf 1ttd2

df d1t td 2

1

3ej2pftd

4

q

q

ej2pftd

ej2pft

df

1

3Aej2pftd

4

Aej2pftd

;

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-99-2048.jpg)

![80 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

Let y(t) (2At/t)Π (t/t). Sketch dy(t)/dt and use Eq. (27) to find V(f).

2.6 DISCRETE TIME SIGNALS AND THE DISCRETE

FOURIER TRANSFORM

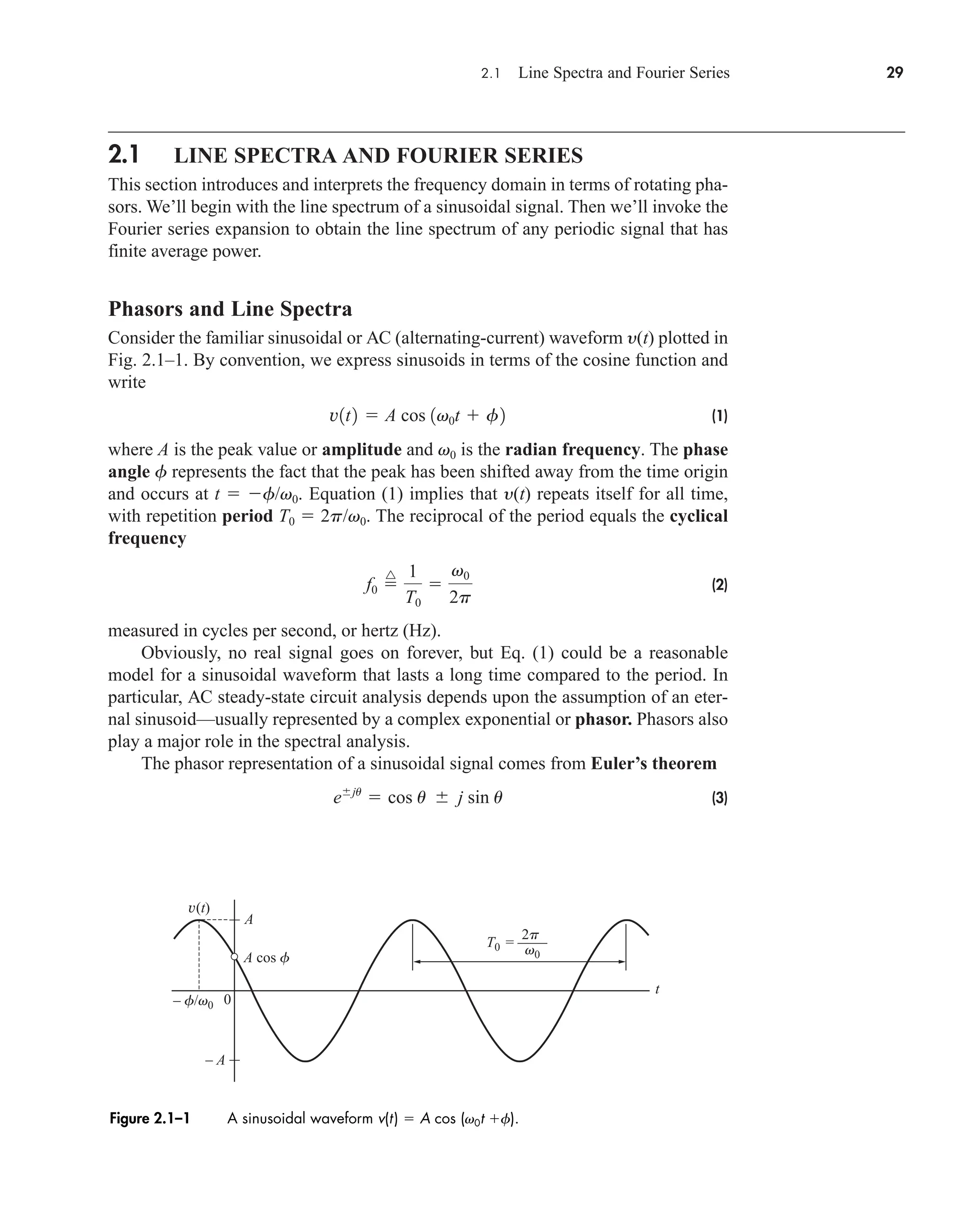

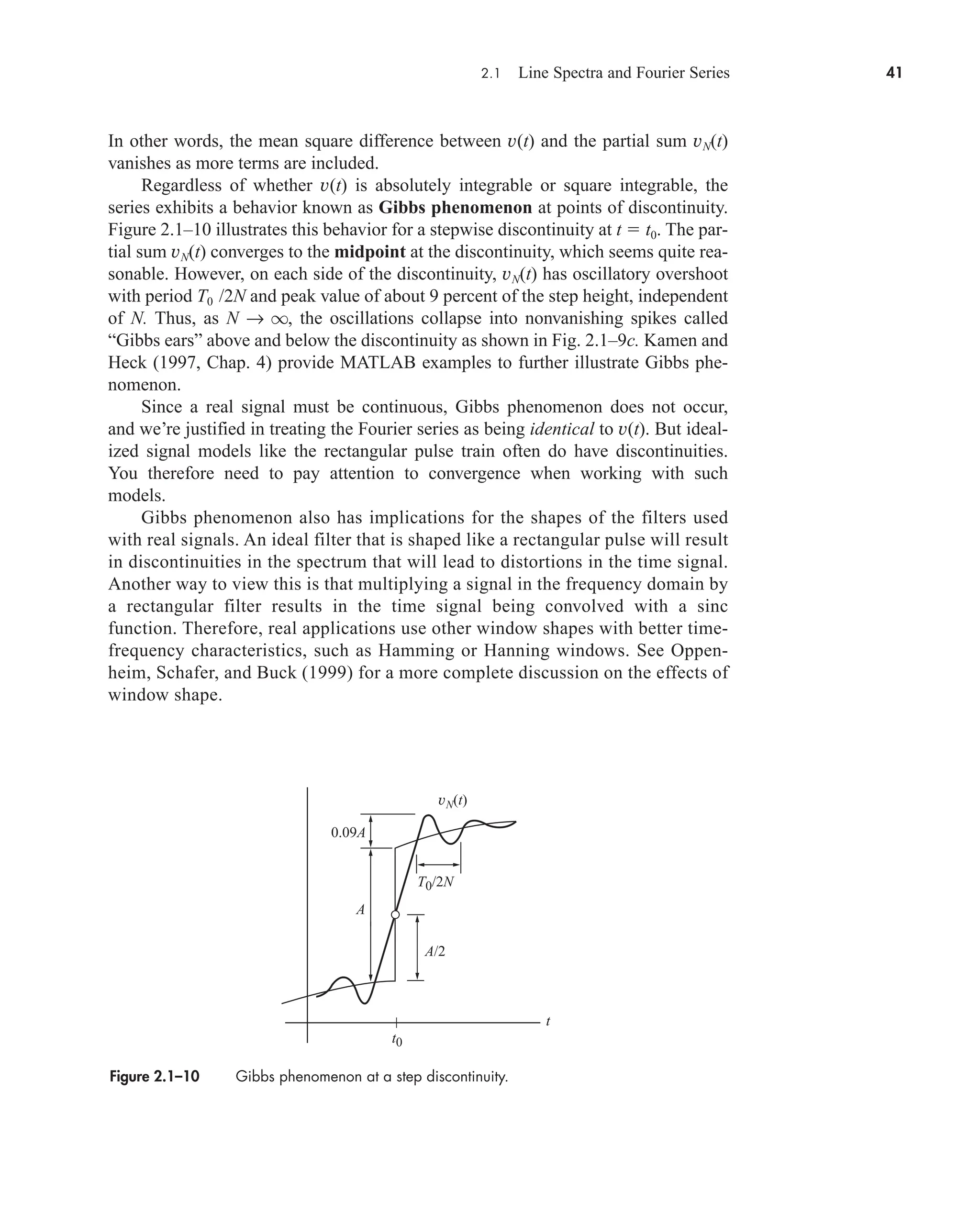

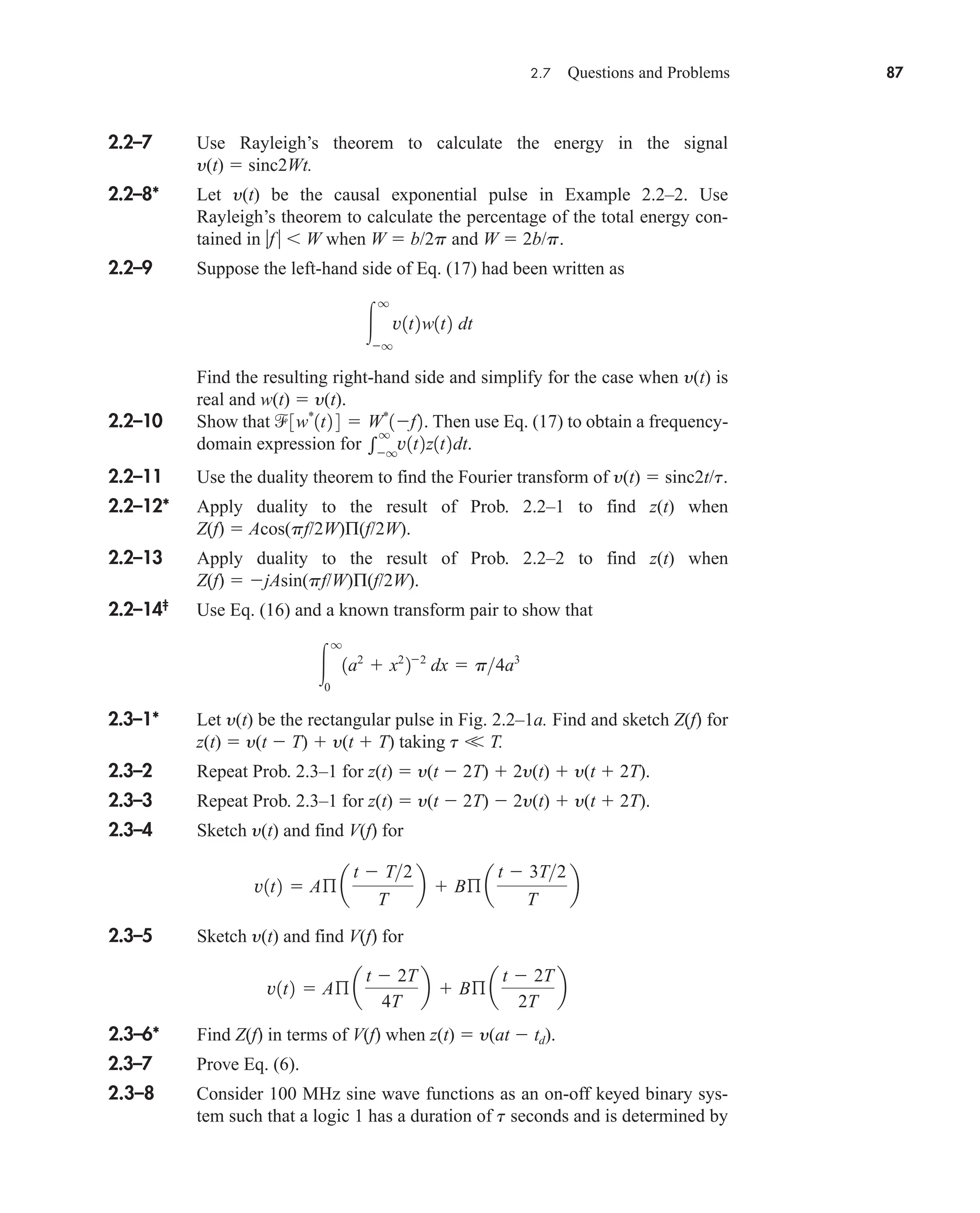

It will be shown in Sect. 6.1 that if we sample a signal at a rate at least twice its

bandwidth, then it can be completely represented by its samples. Consider a rectan-

gular pulse train that has been sampled at rate fs 1/Ts and is shown in Fig. 2.6–1a.

It is readily observed that the sampling interval is t Ts. The samples can be

expressed as

(1a)

Furthermore, if our sampler is a periodic impulse function, we have

(1b)

Then we drop the Ts to get

(1c)

where x(k) is a discrete-time signal, an ordered sequence of numbers, possibly com-

plex, and consists of k 0, 1, . . . N 1, a total of N points.

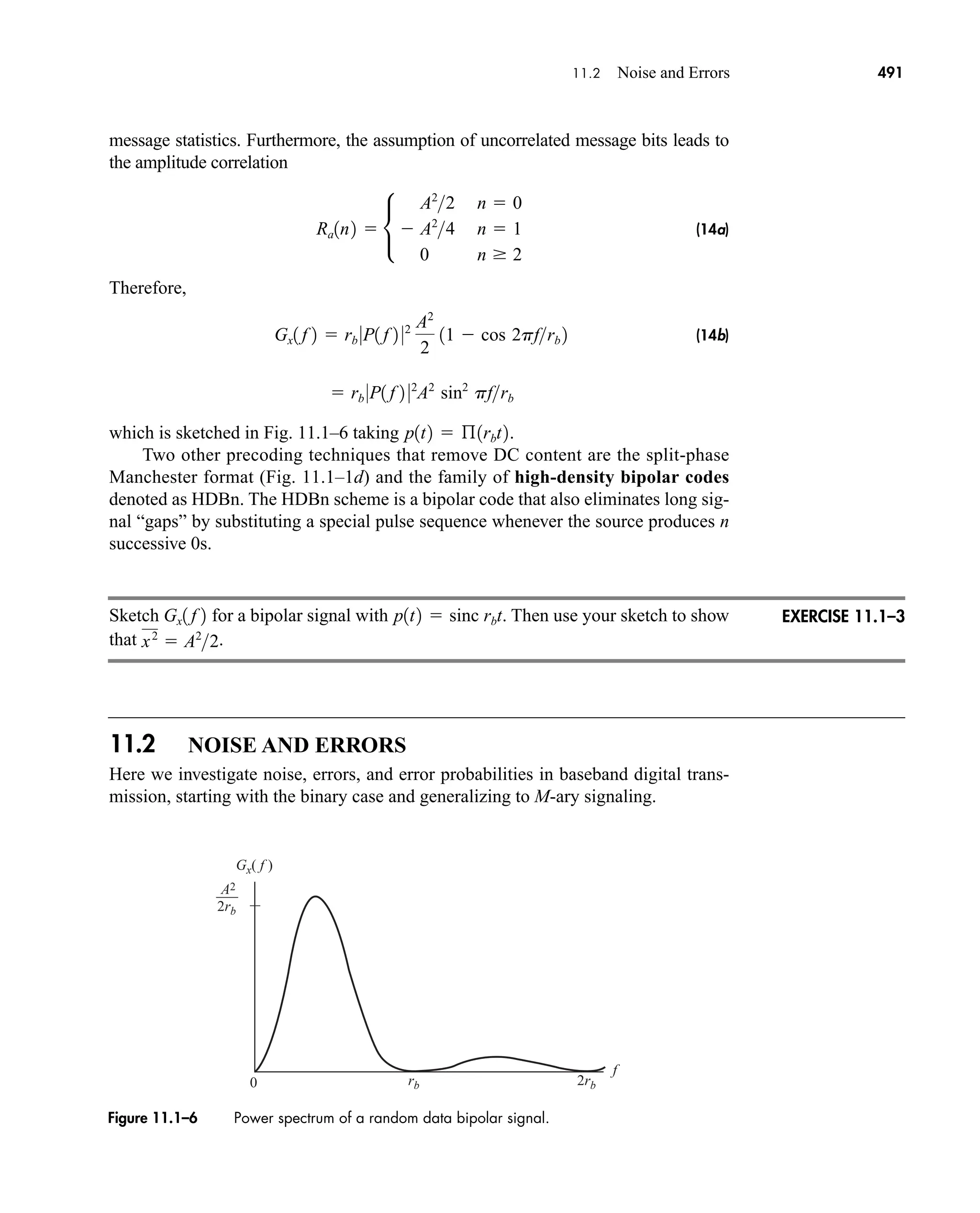

It can be shown that because our sampler is a periodic impulse function

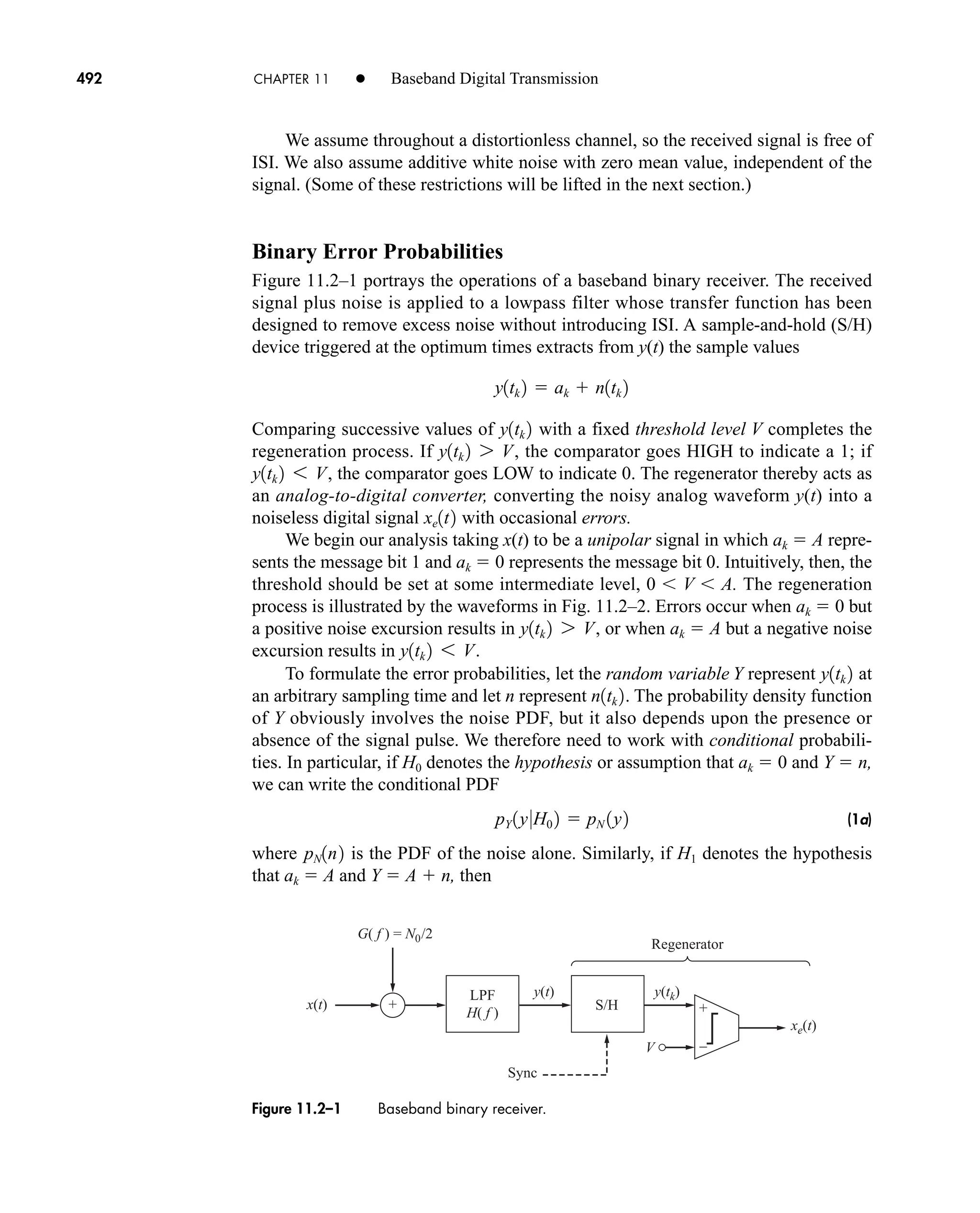

(t kTs), then we can replace the Fourier transform integral of Eq. (4) of Sect. 2.2

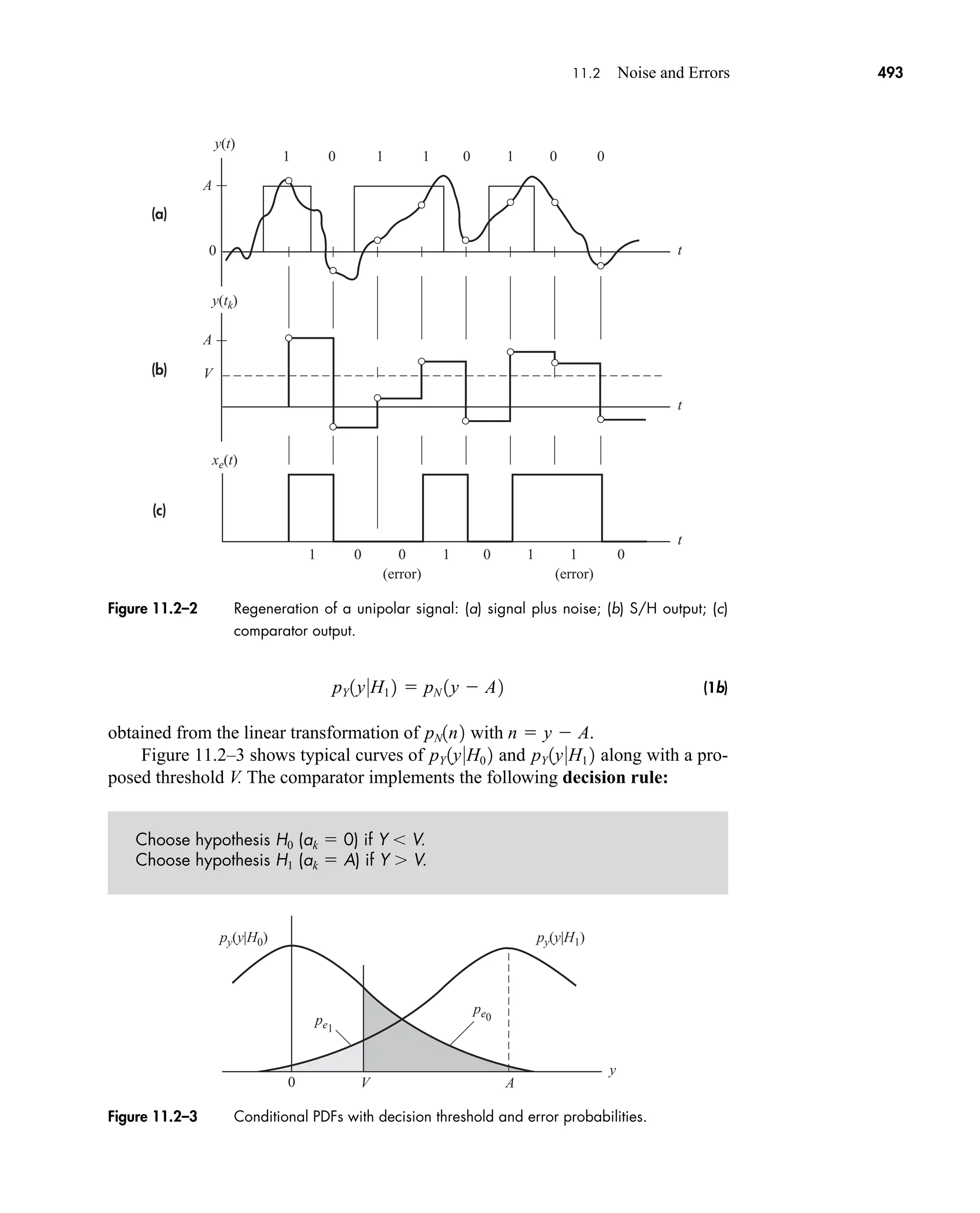

with a summation operator, giving us

(2)

Alternatively, we can get Eq. (2) by converting the integral of Eq. (4), Sect. 2.2, to a sum-

mation and changing dt → t Ts. Function X(n) is the Discrete Fourier transform

(DFT), written as DFT[x(k)] and consisting of N samples, where each sample is spaced

at a frequency of 1/(NTs) fs/N Hz. The DFT of the sampled signal of Fig. 2.6–1a is

shown in Fig. 2.6–1b. Note how the DFT spectrum repeats itself every N samples or

every fs Hz. The DFT is computed only for positive N. Note the interval from n → (n 1)

represents fs /N Hz, and thus the discrete frequency would then be

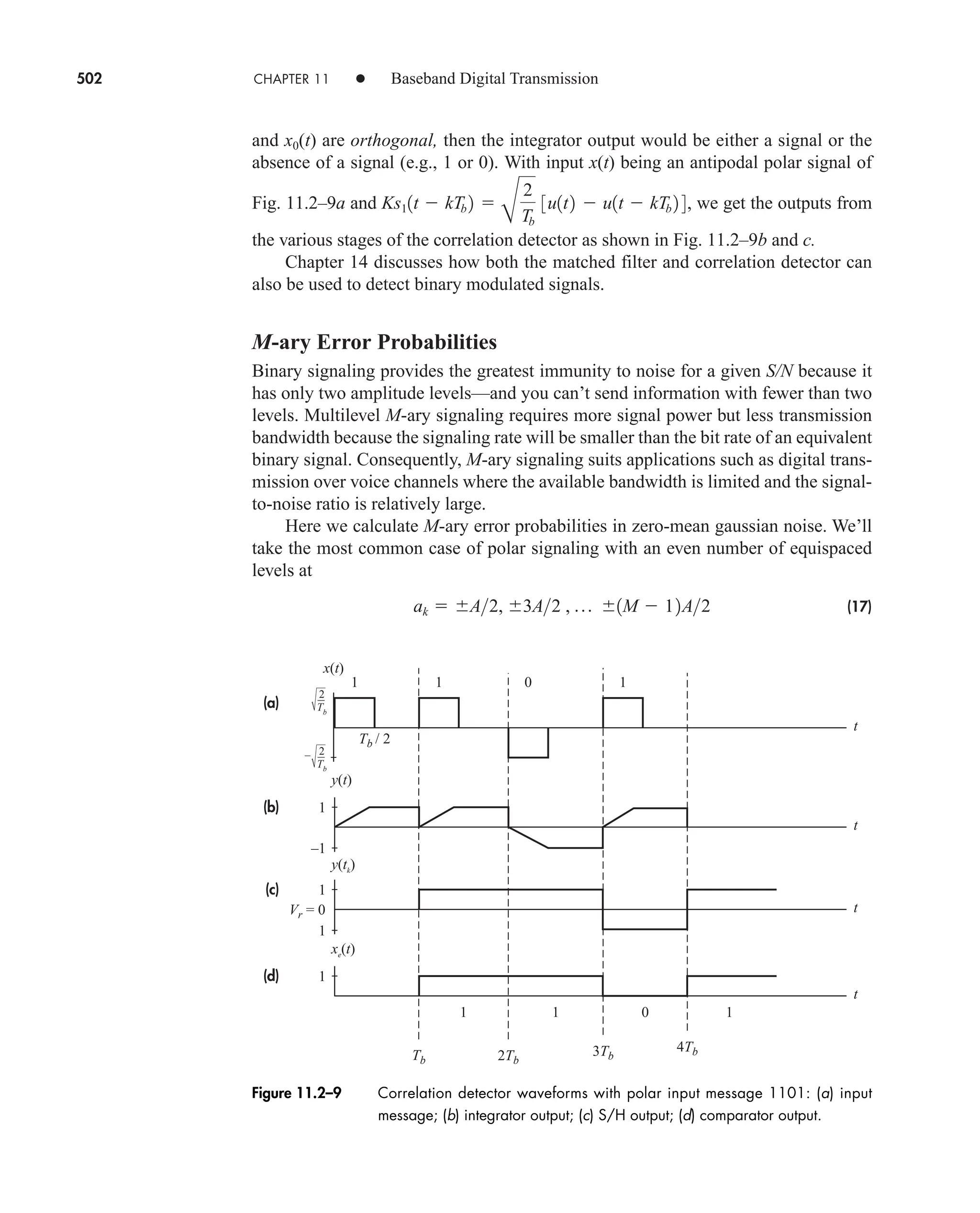

(3)

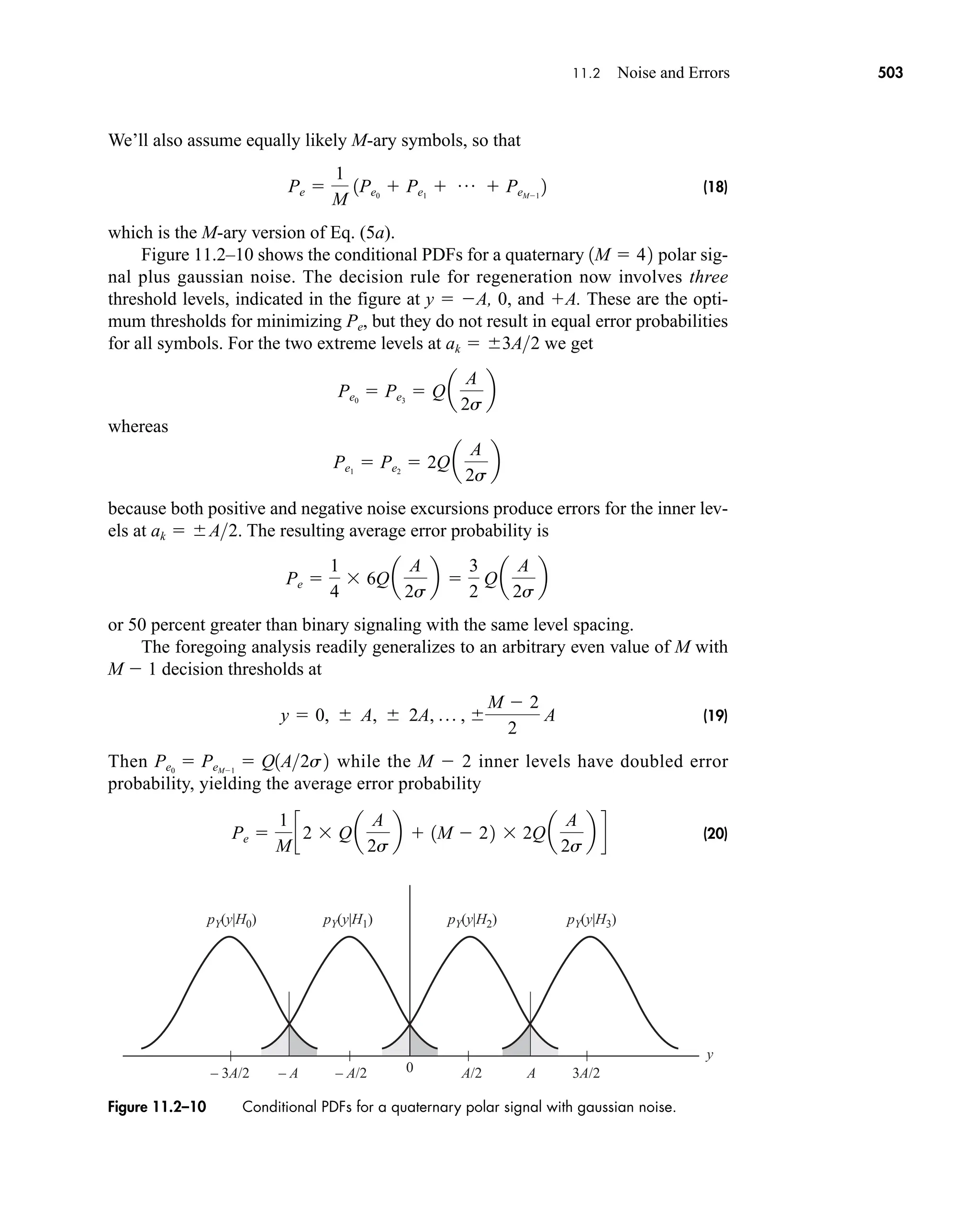

Observe that both x(k) and X(n) are an ordered sequence of numbers and thus can

easily be processed by a computer or some other digital signal processor (DSP).

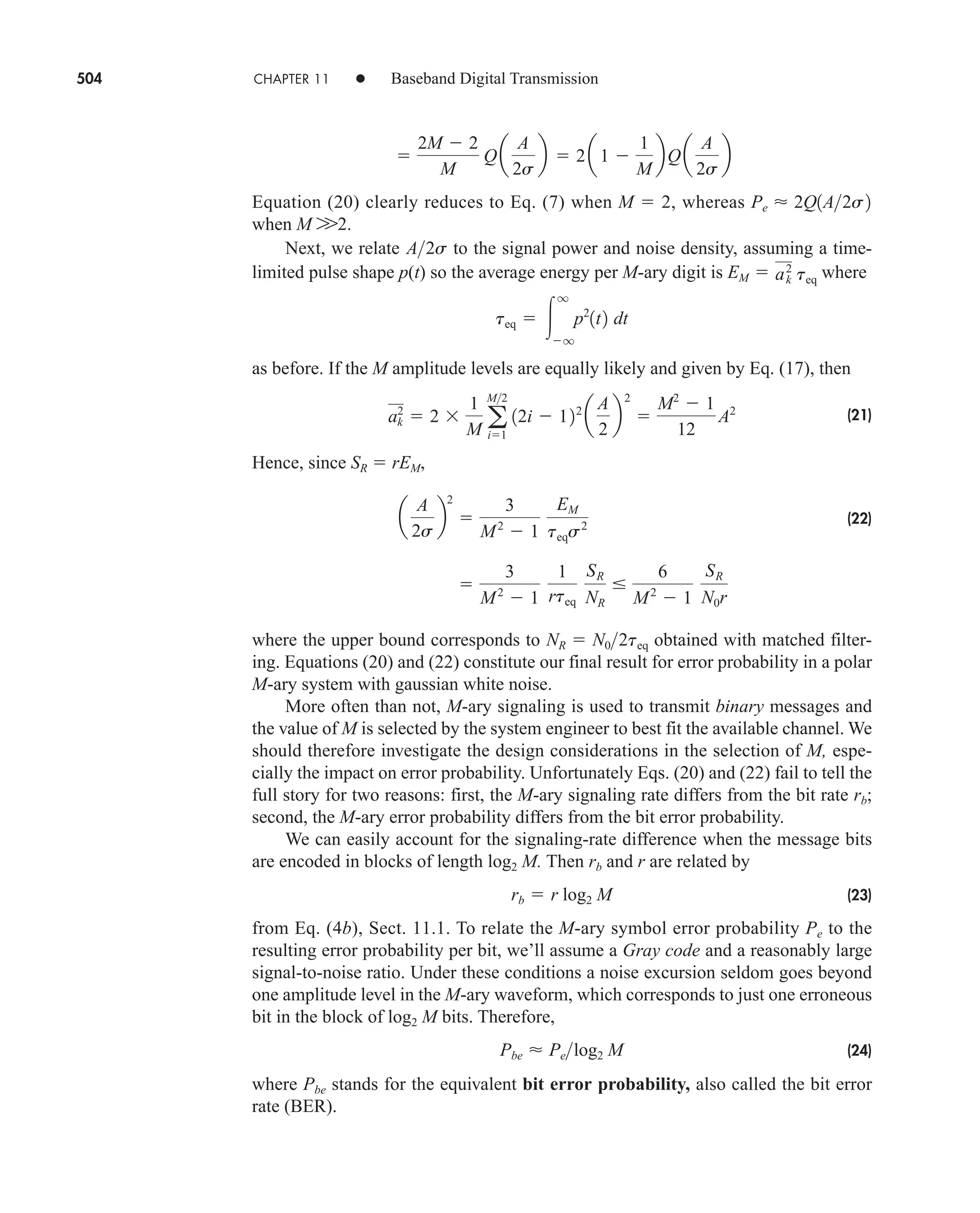

n S fn nfsN

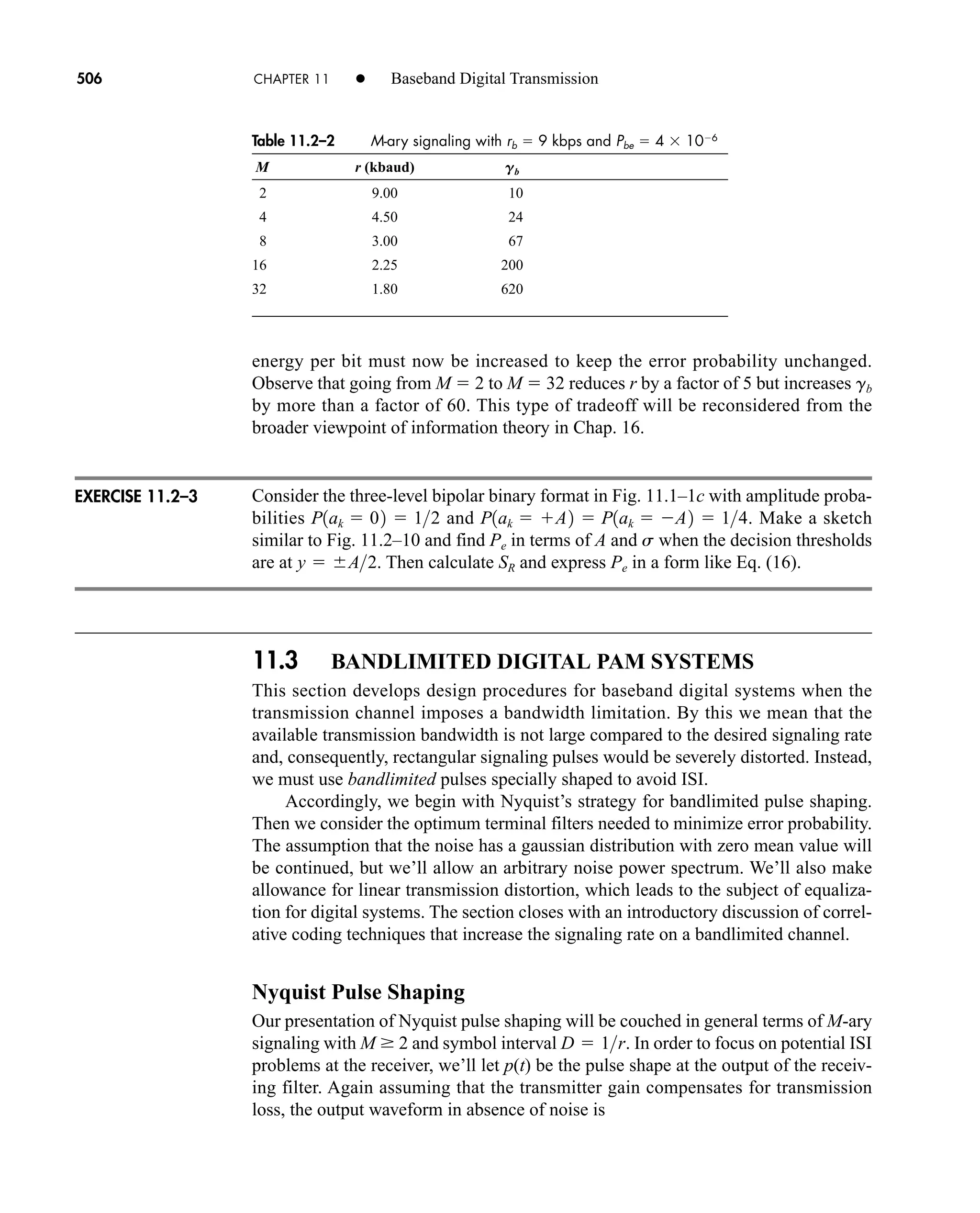

X1n2 a

N1

k0

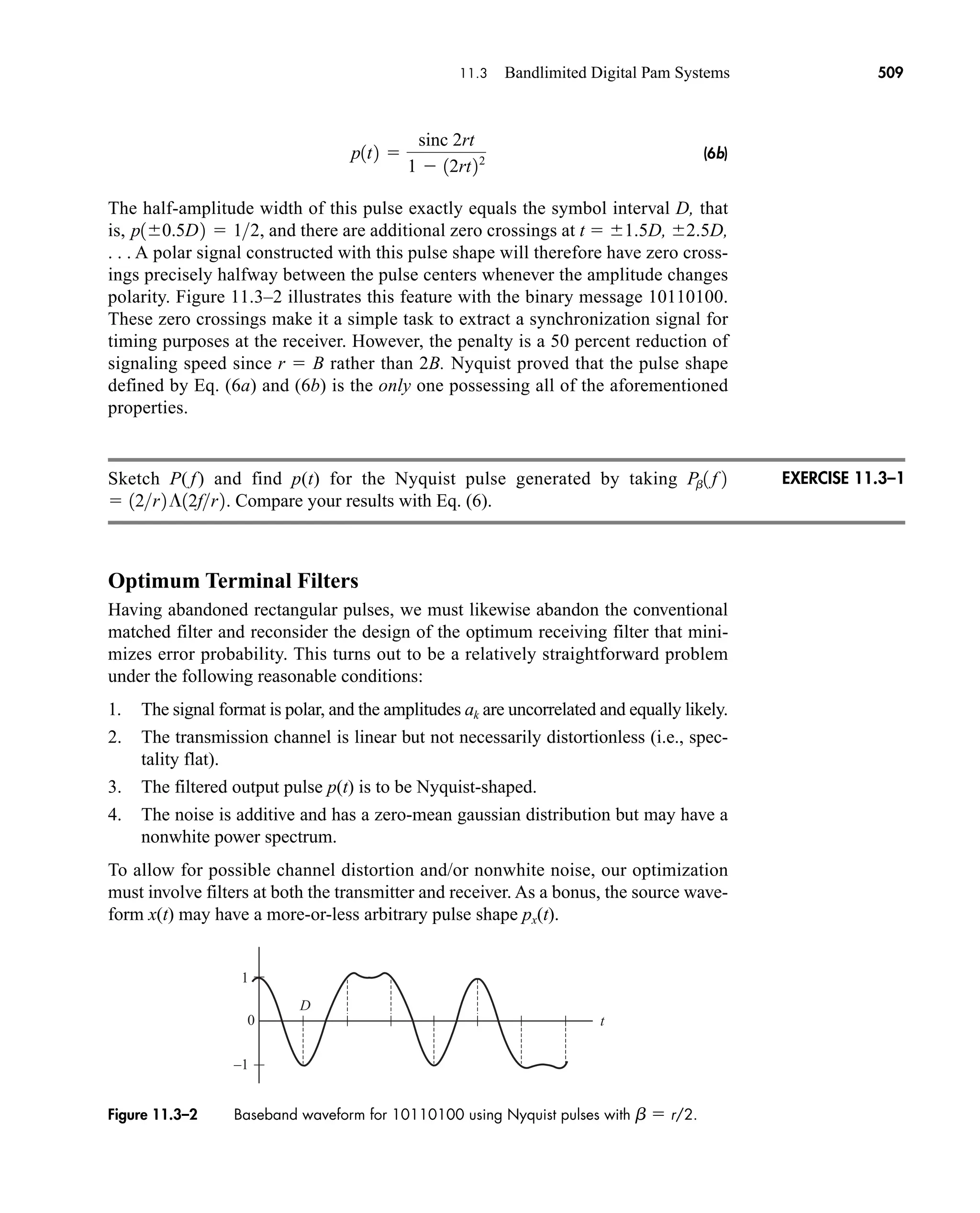

x1k2ej2pnkN

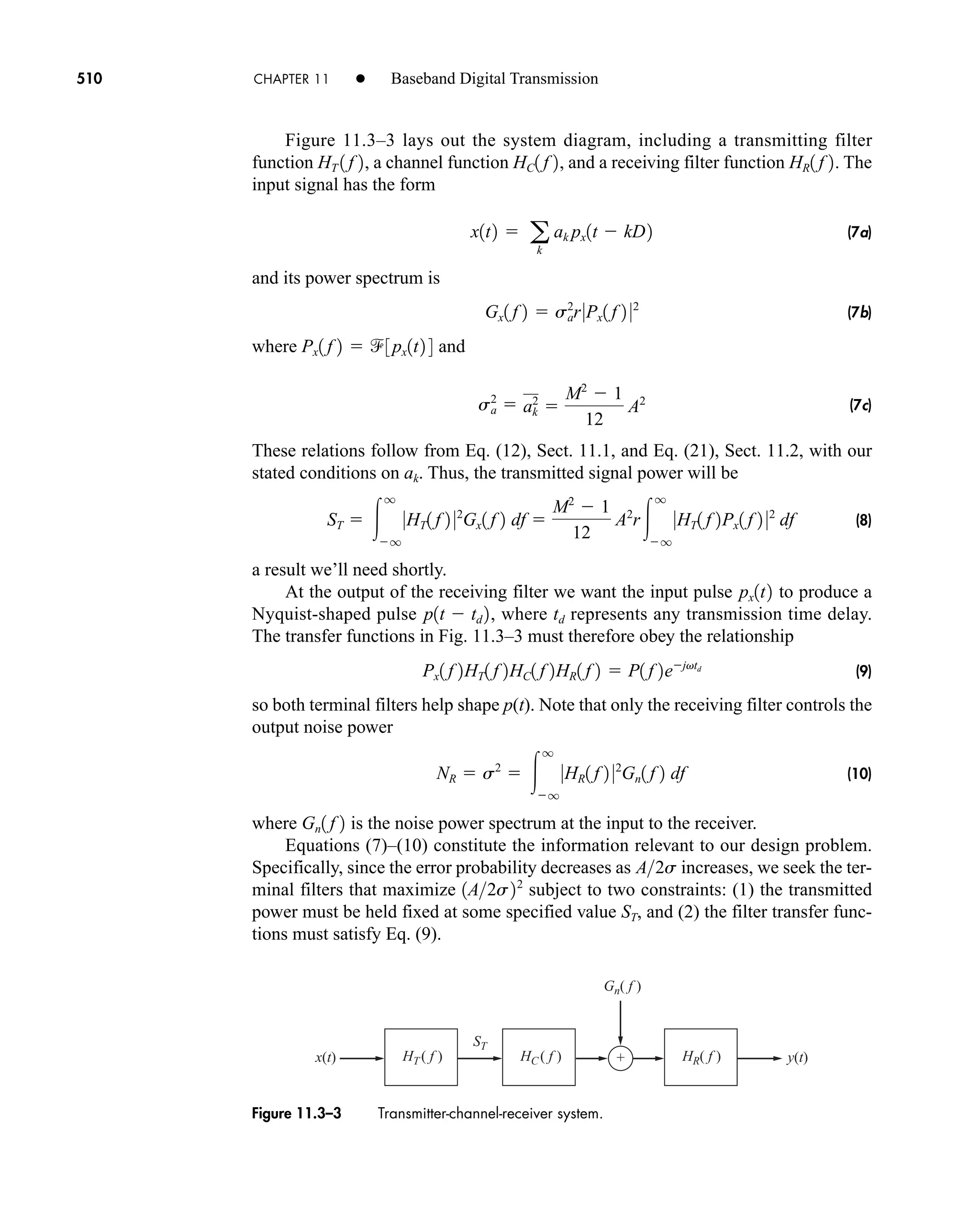

n 0, 1 p N

x1k2 x1kTs 2

x1kTs 2 x1t2d1t kTs 2

x1t2|tkTs

x1kTs 2

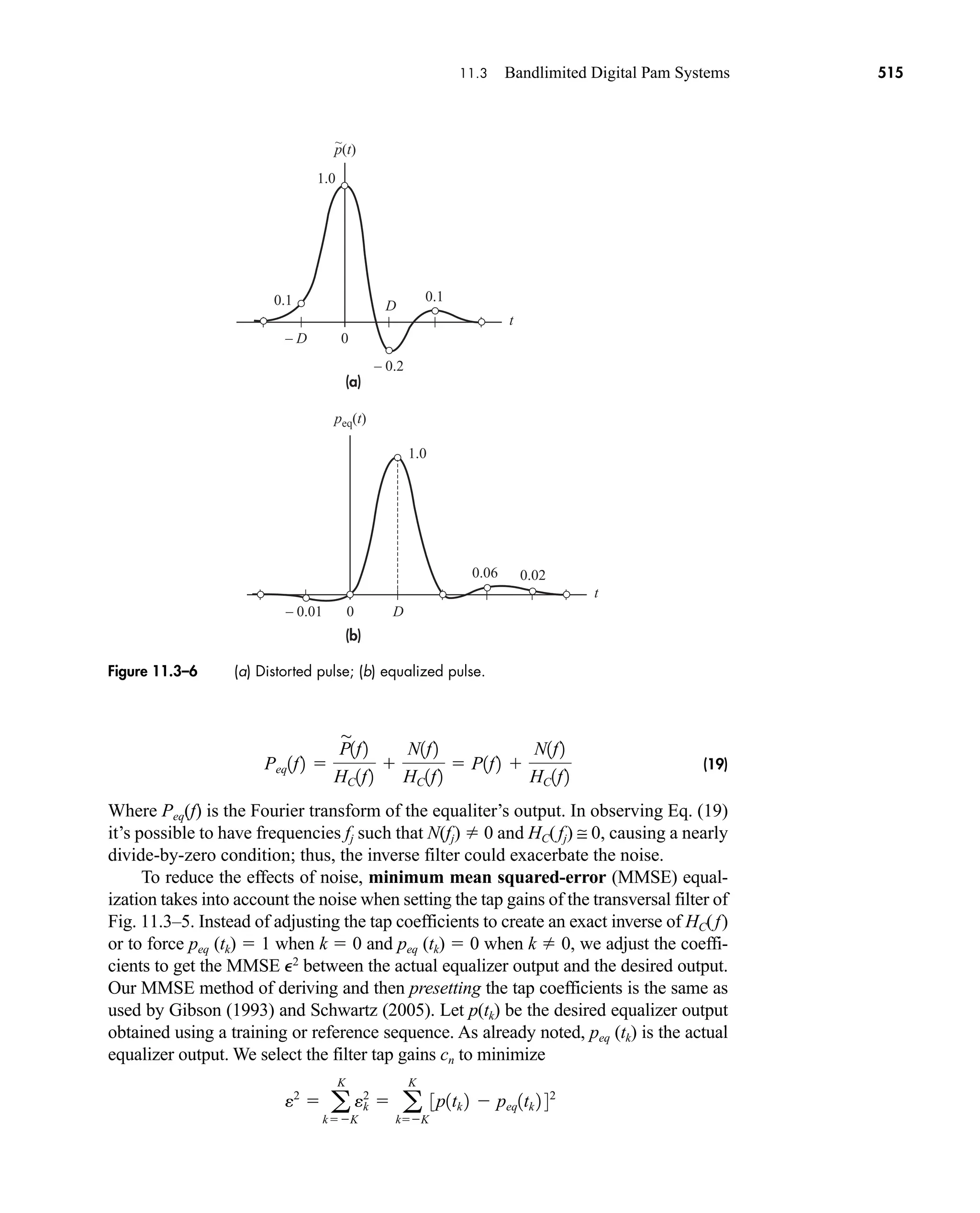

EXERCISE 2.5–3

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-102-2048.jpg)

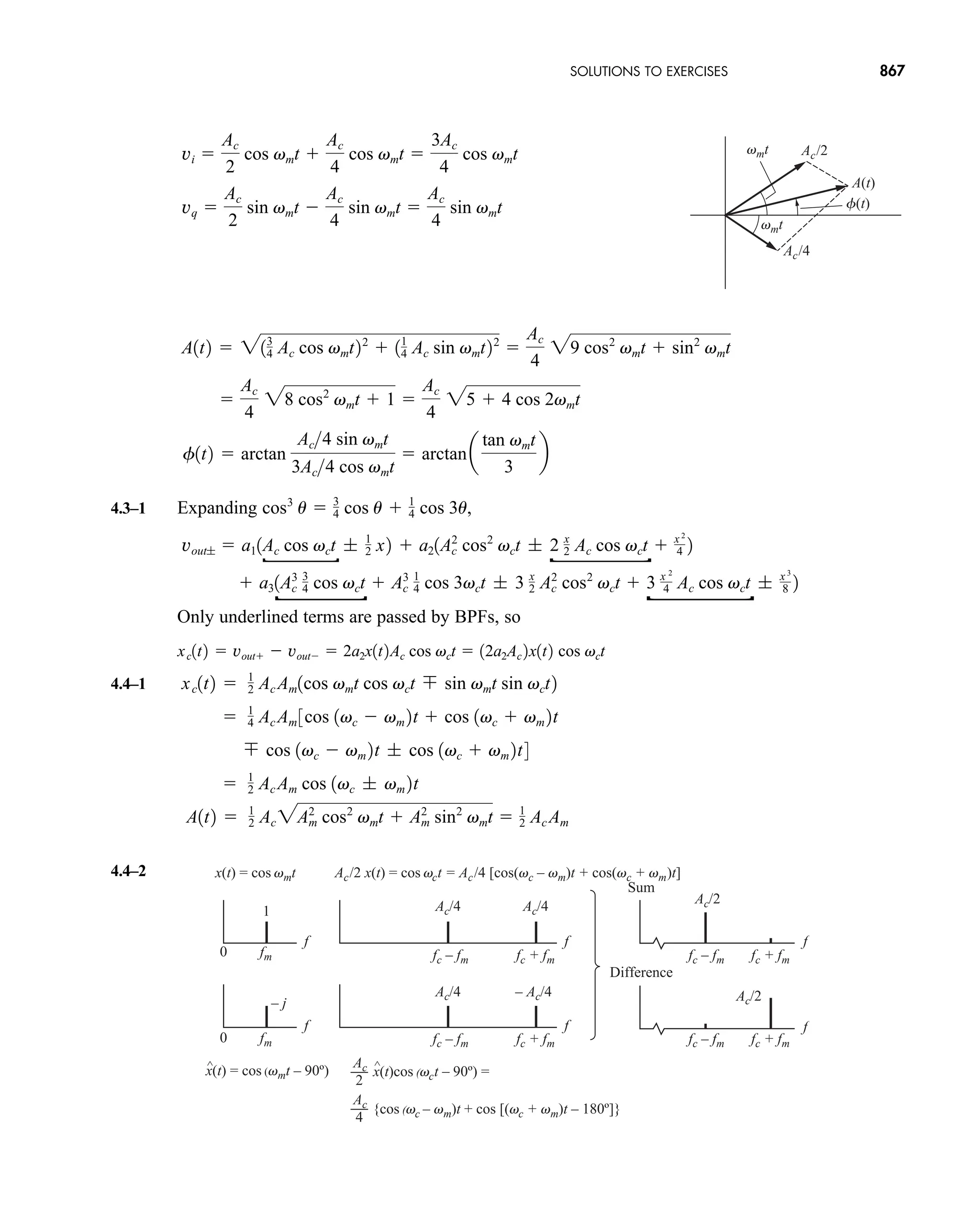

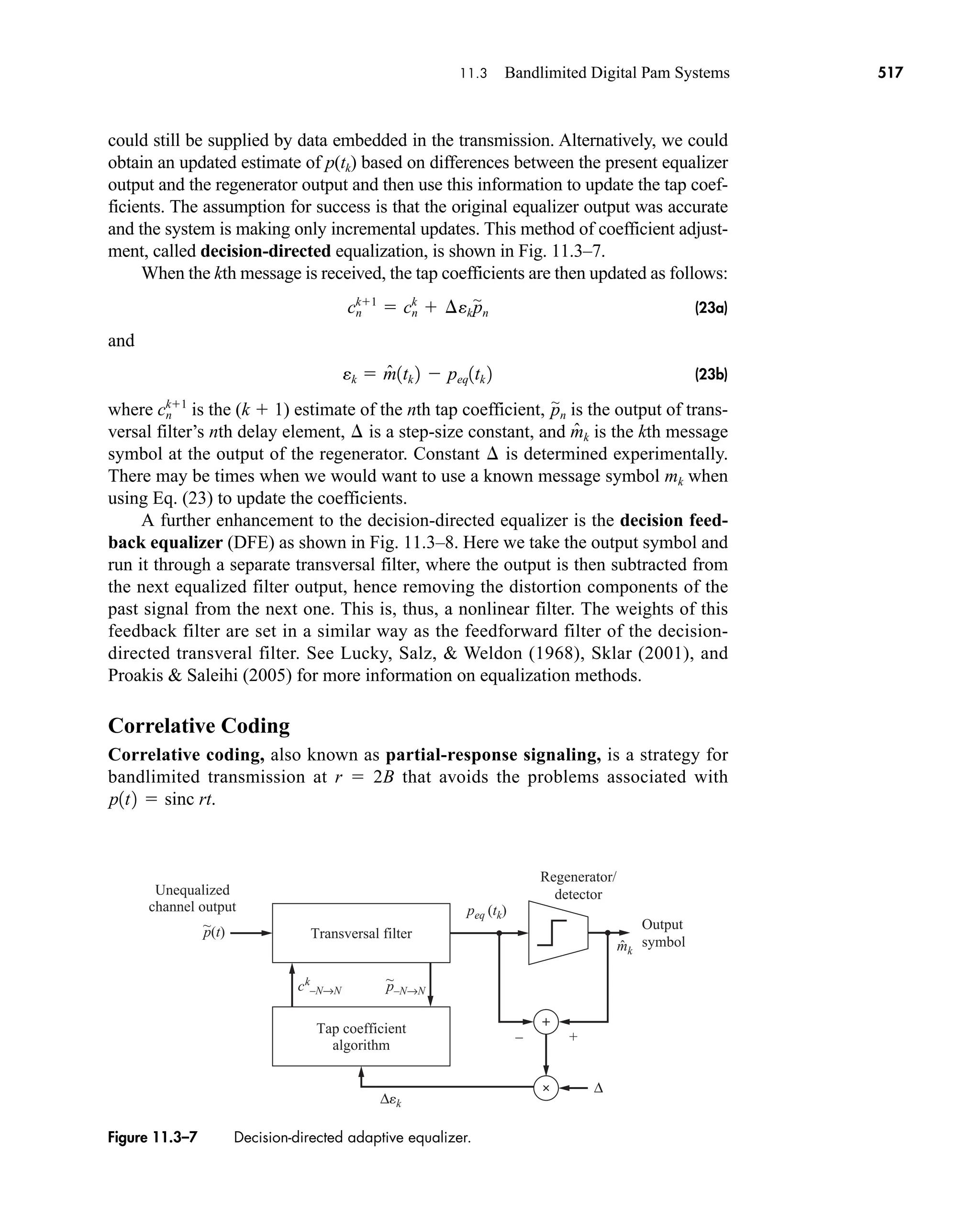

![2.6 Discrete Time Signals and the Discrete Fourier Transform 81

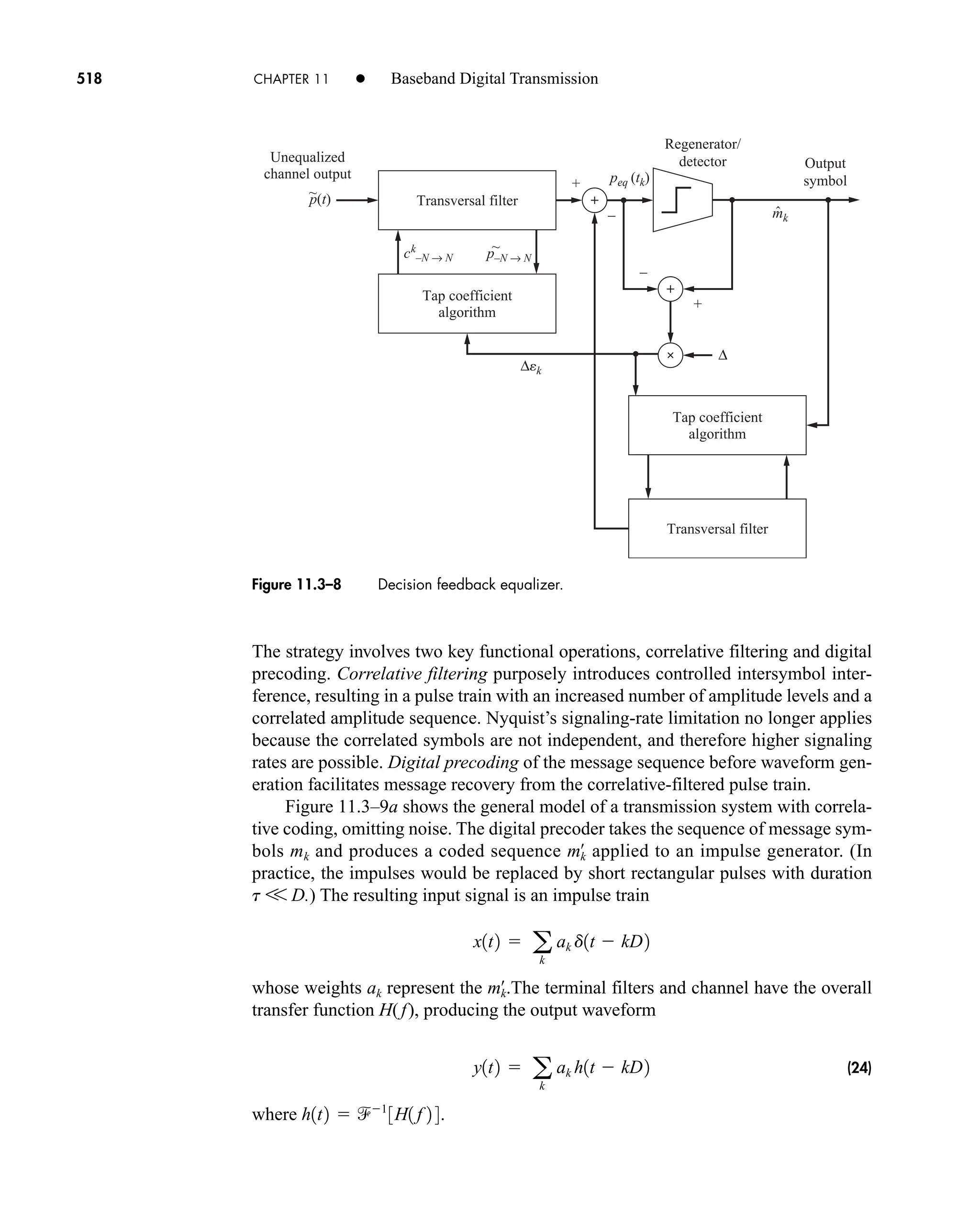

The corresponding inverse discrete Fourier transform (IDFT) is

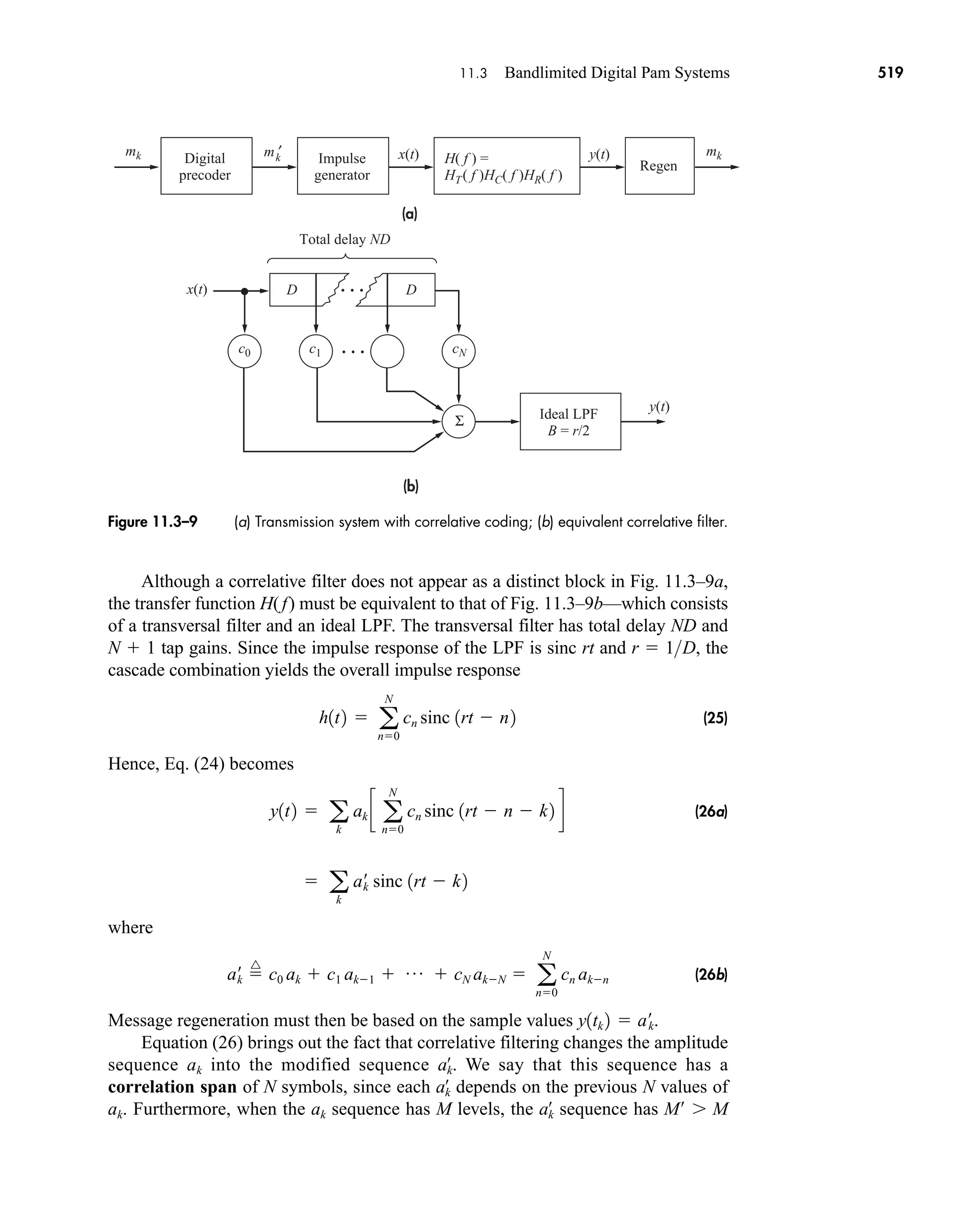

(4)

Equations (2) and (4) can be separated into their real and imaginary components giving

and

Sect. 6.1 will discuss how x(t) is reconstructed from from X(n) or x(k).

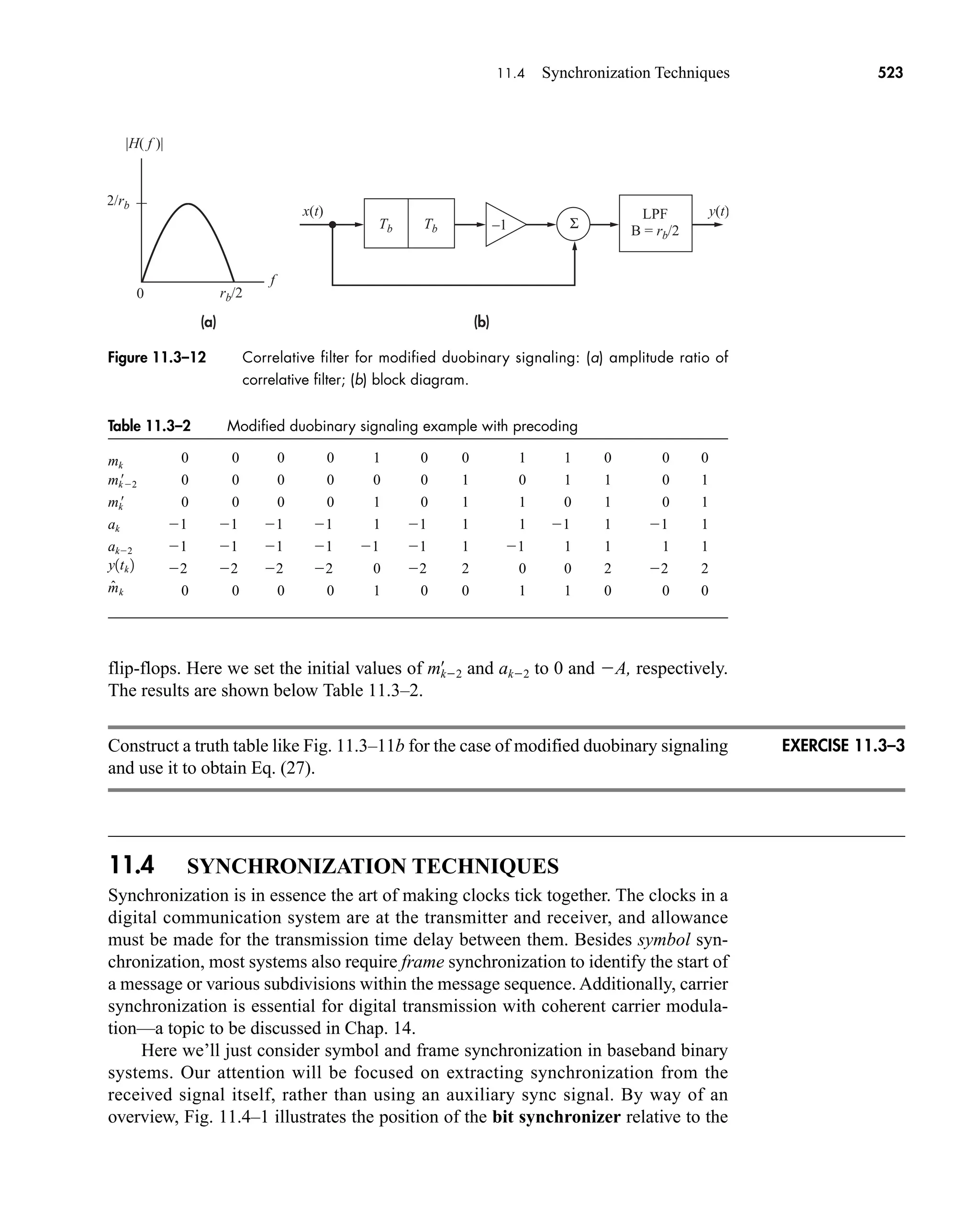

In examining Eqs. (2) and (4) we see that the number of complex multiplica-

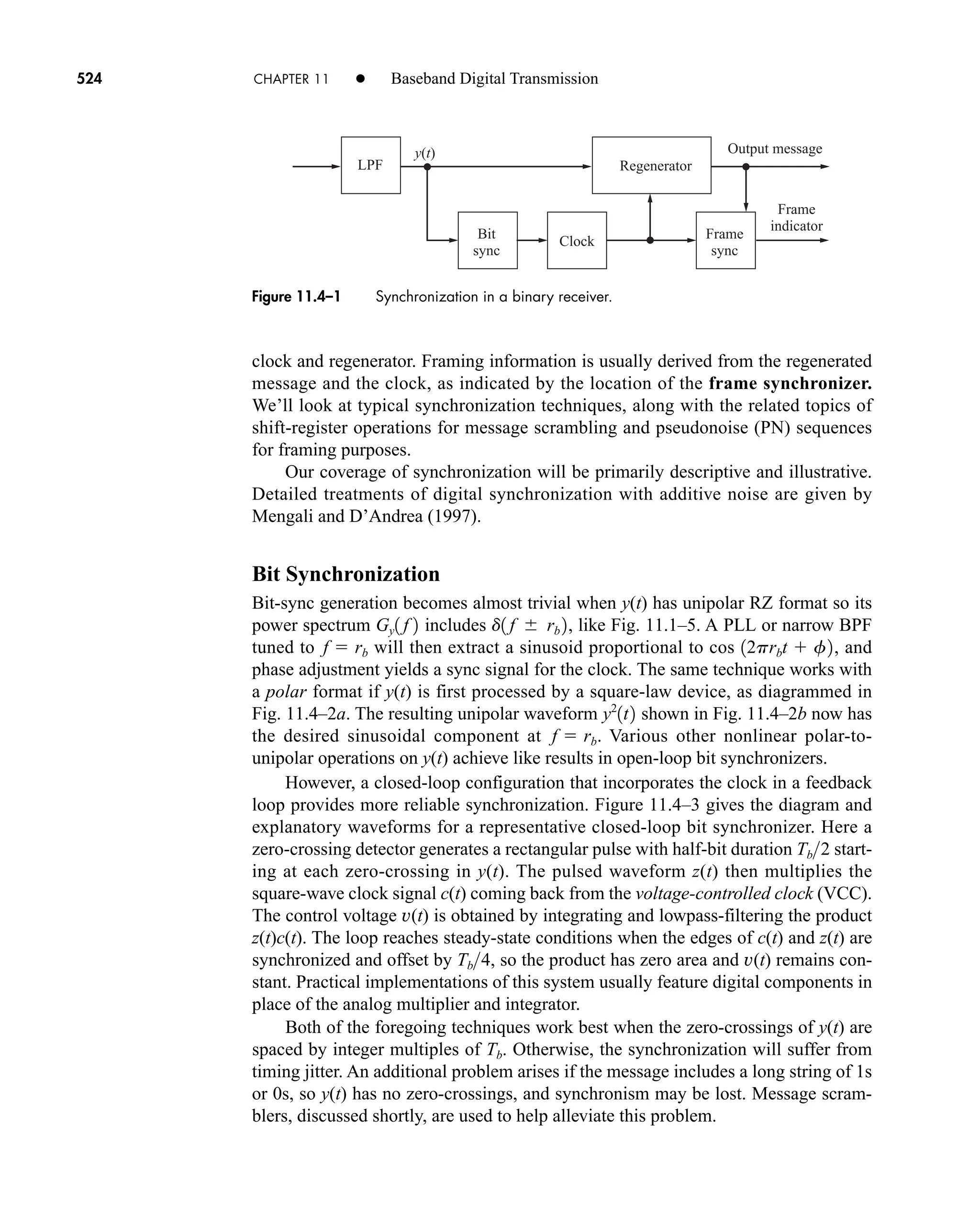

tions required to do a DFT or IDFT is N2

. If we are willing to work with N 2y

sam-

ples, where y is an integer, we can use the Cooley-Tukey technique, otherwise

known as the fast Fourier transform (FFT) and inverse FFT (IFFT), and thereby

reduce the number of complex multiplications to This technique greatly

N

2

log2 N.

xR1k2 Re3x1k2 4 and xI 1k2 Im3x1k2 4.

XR1n2 Re3X1n2 4 and XI 1n2 Im3X1n2 4

x1k2 IDFT3X1n2 4

1

N a

N

n0

X1n2ej2pnkN

k 0, 1 p N

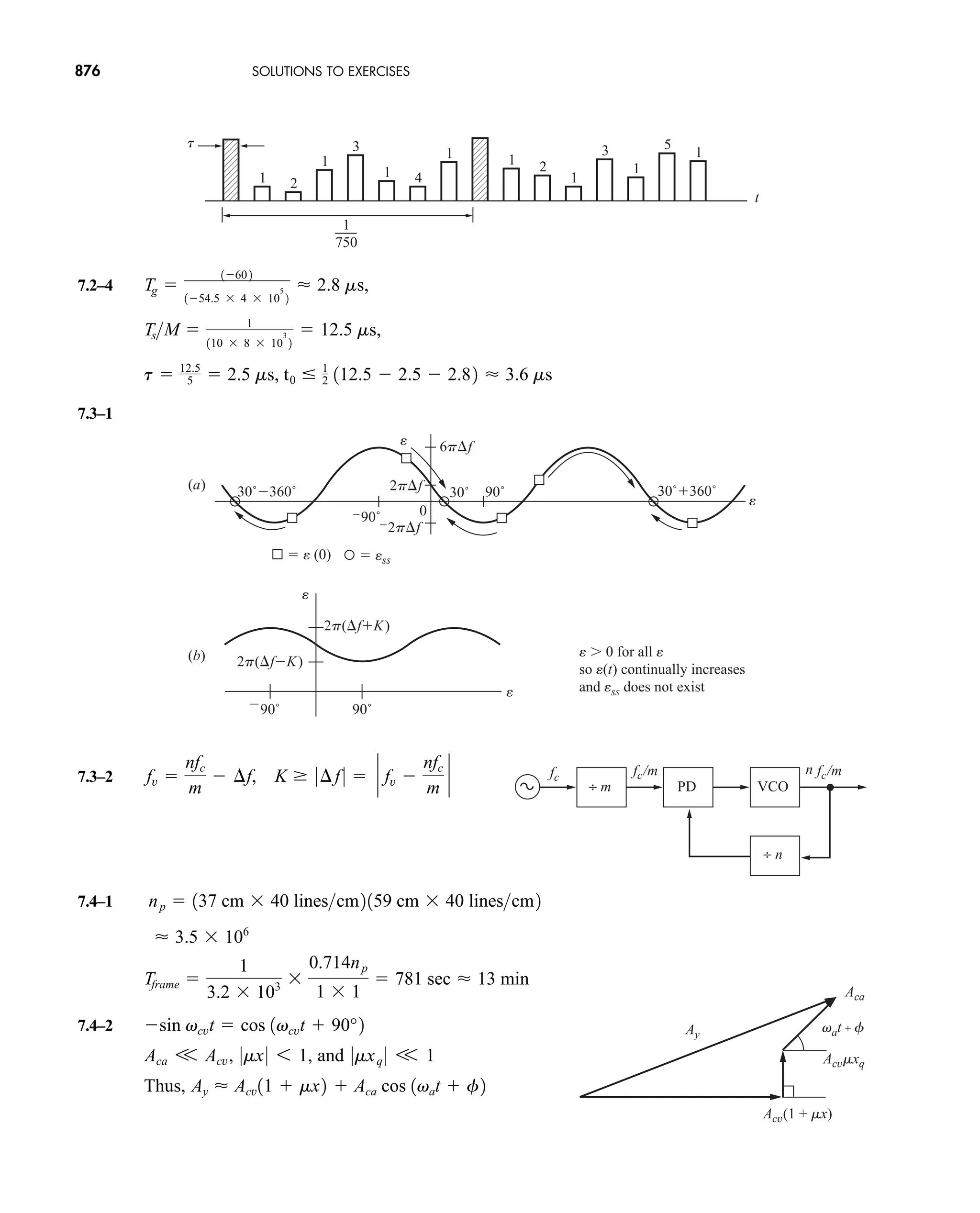

Figure 2.6-1 (a) Sampled rectangular pulse train with (b) corresponding N 16 point

DFT[x(k)]. Also shown is the analog frequency axis.

0 1

0 1 2 3 8 13 14 15 16

8 15 16

f

N

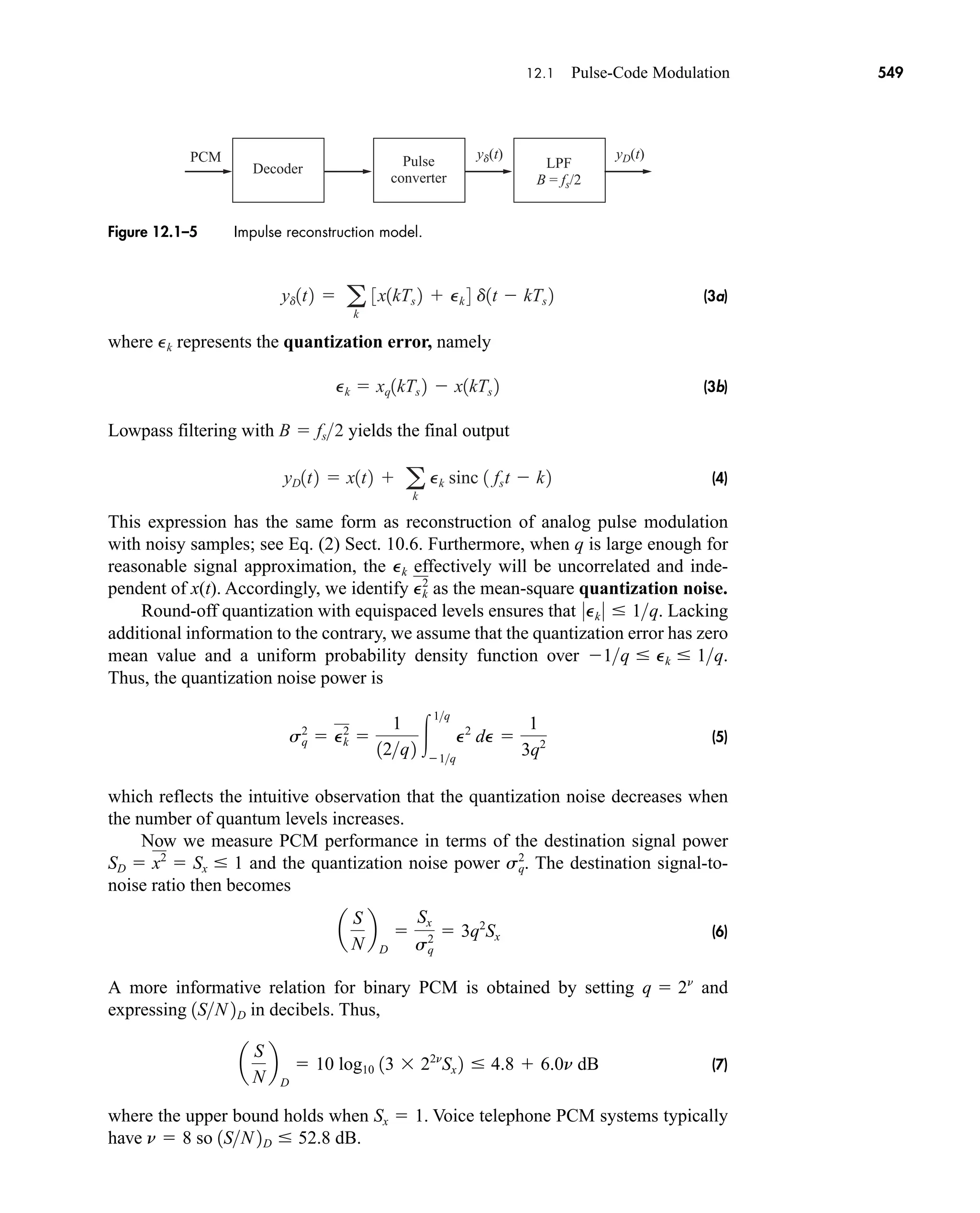

2

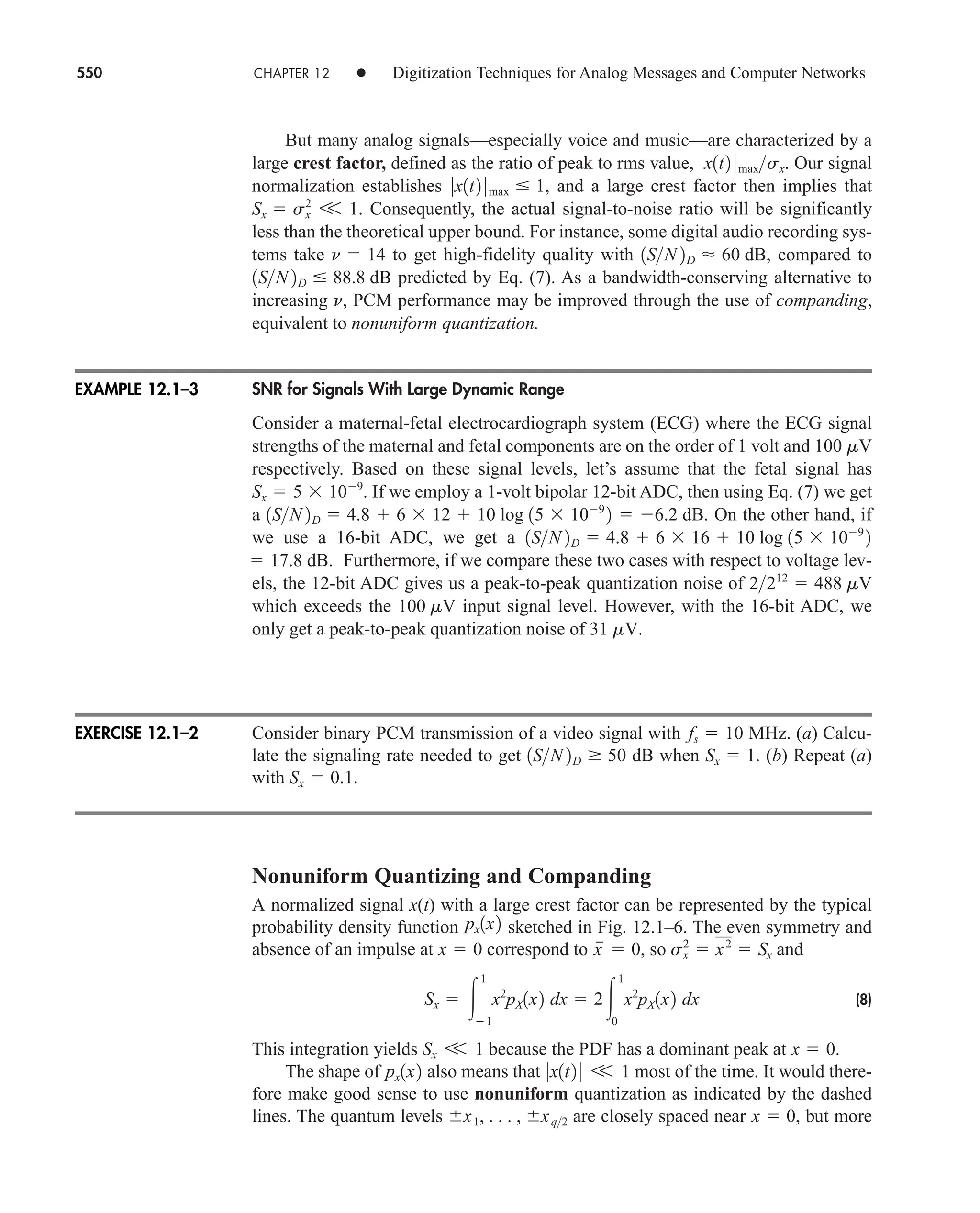

N

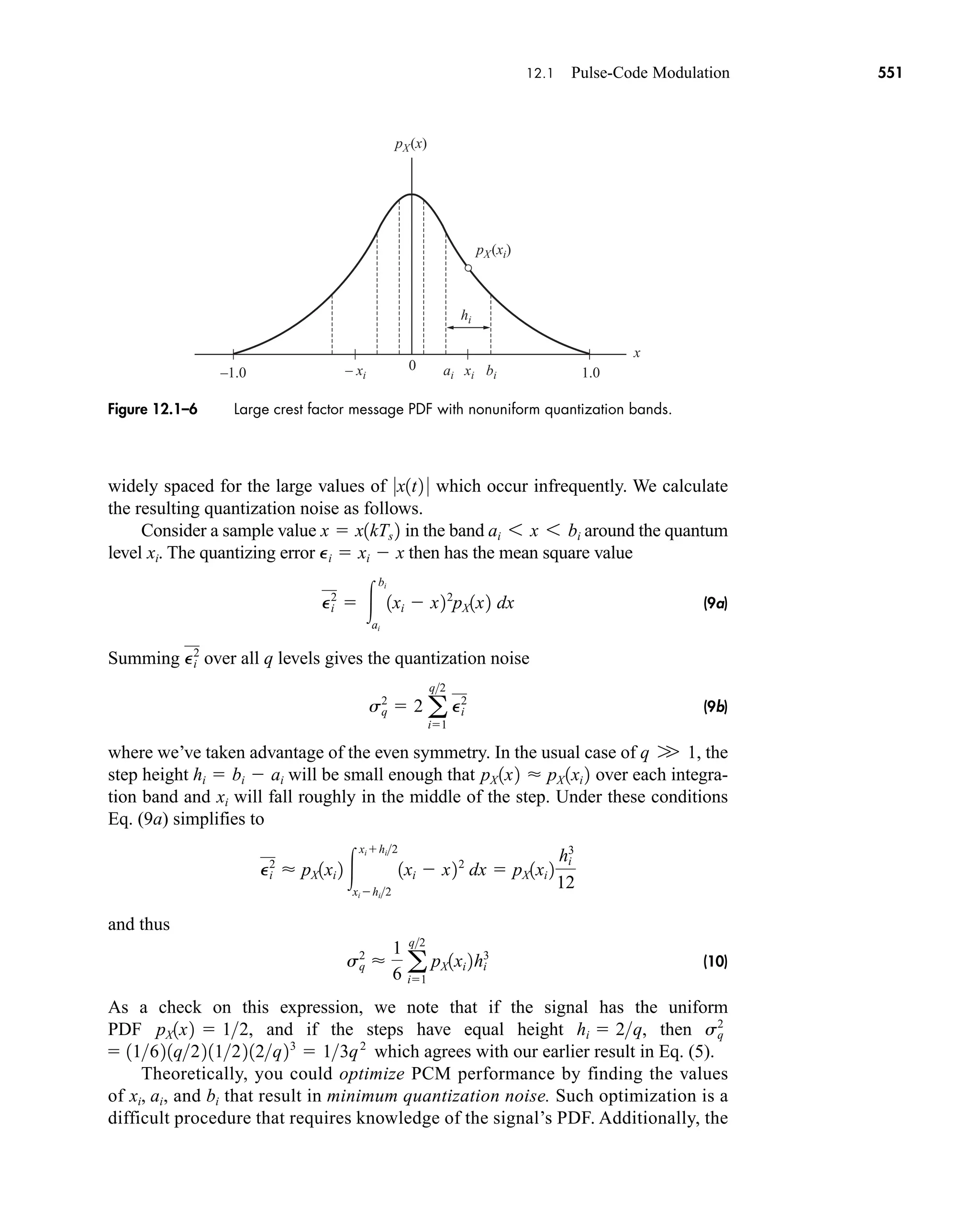

2

0 fs

2

fs

N

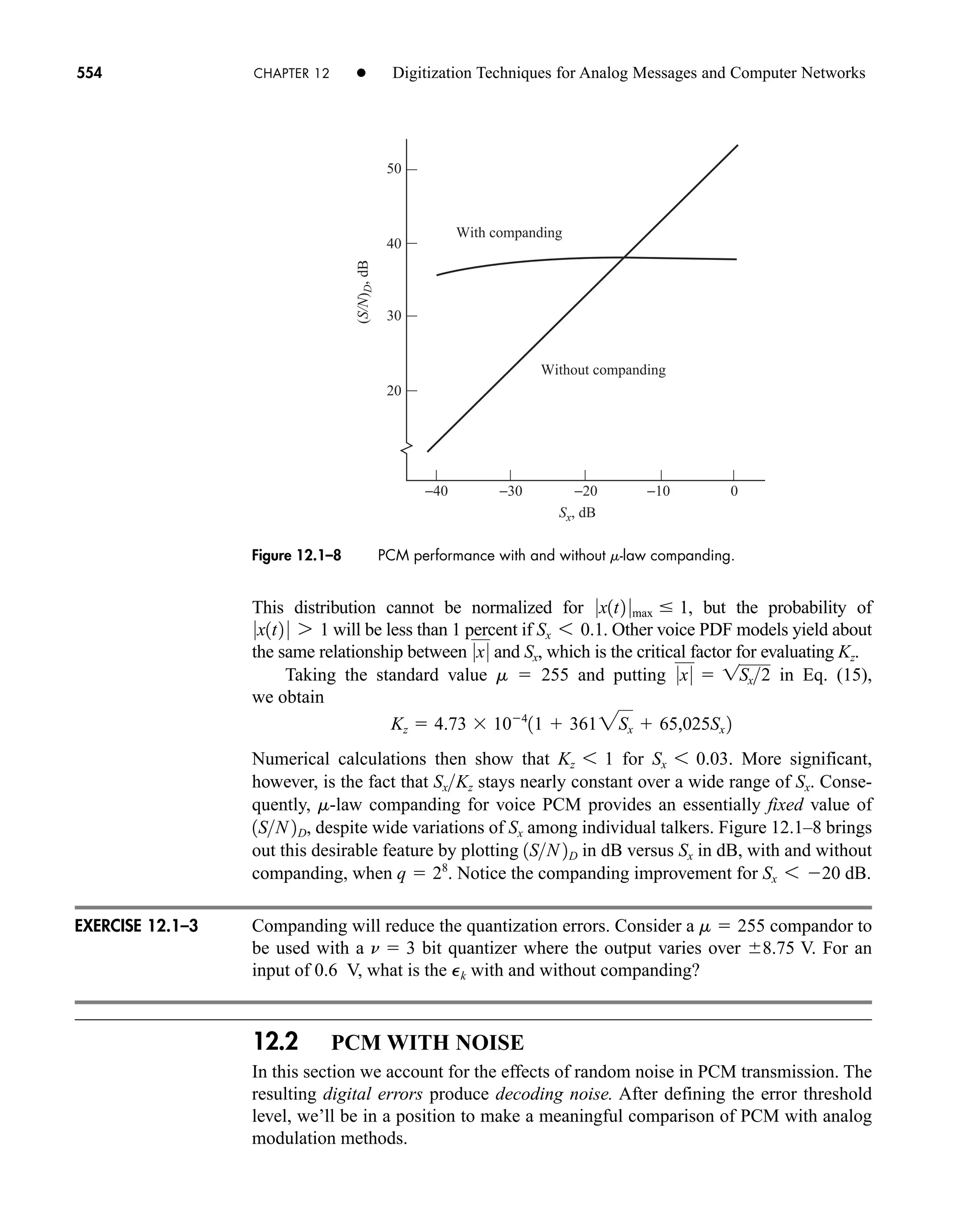

∆f =

∆t = Ts

n

X(n)

x(k)

(b)

N−1

N−1

k

A1

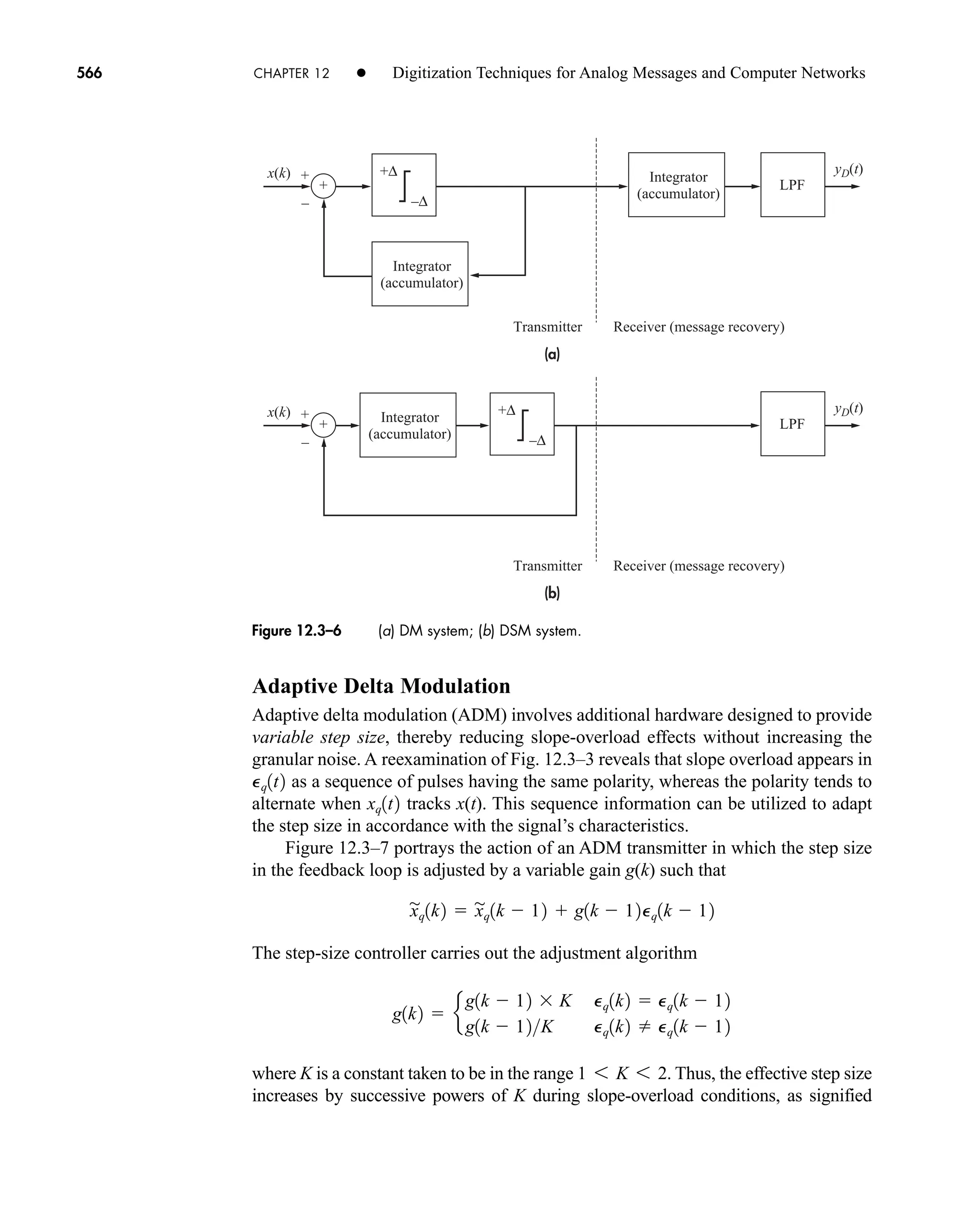

A2

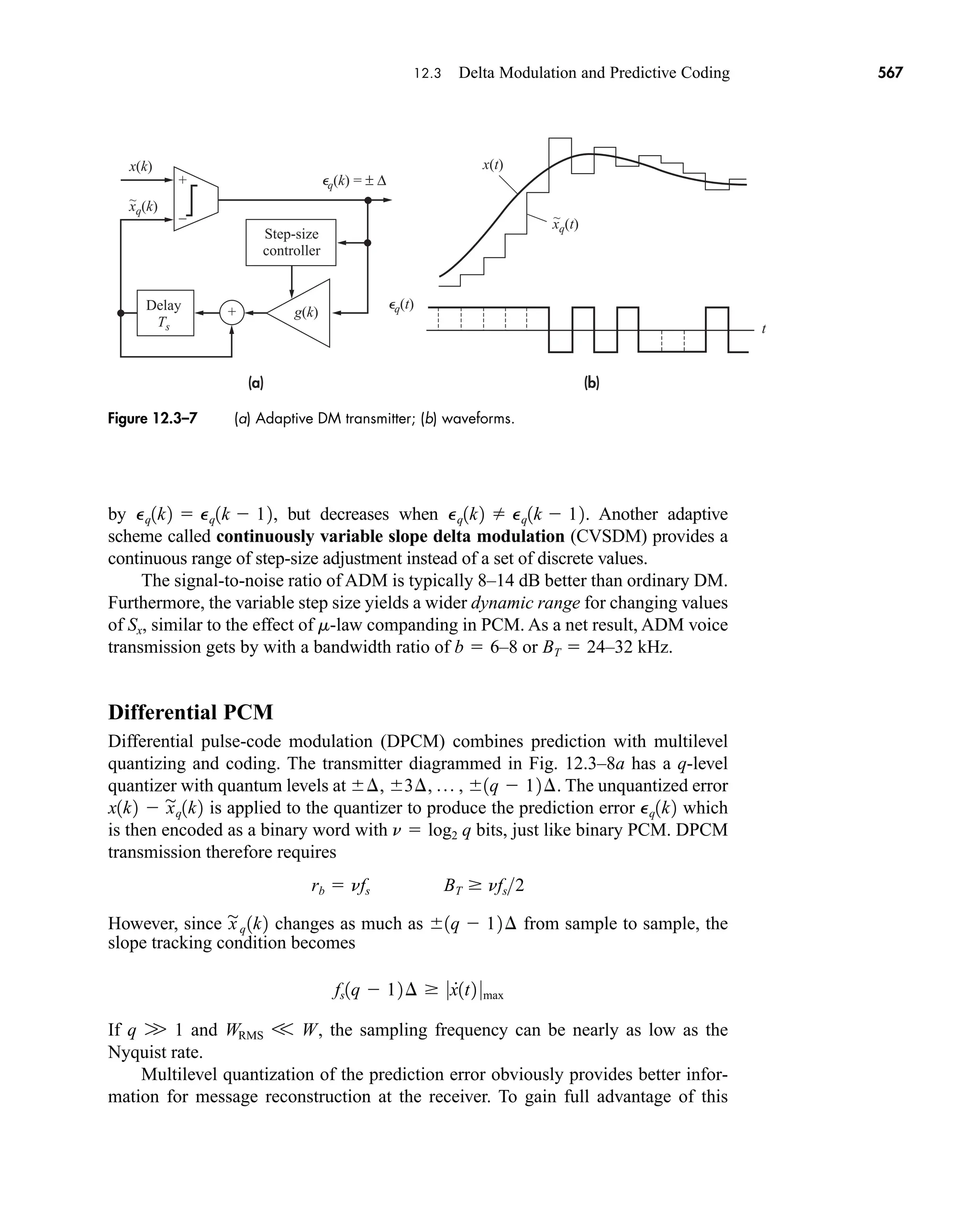

(a)

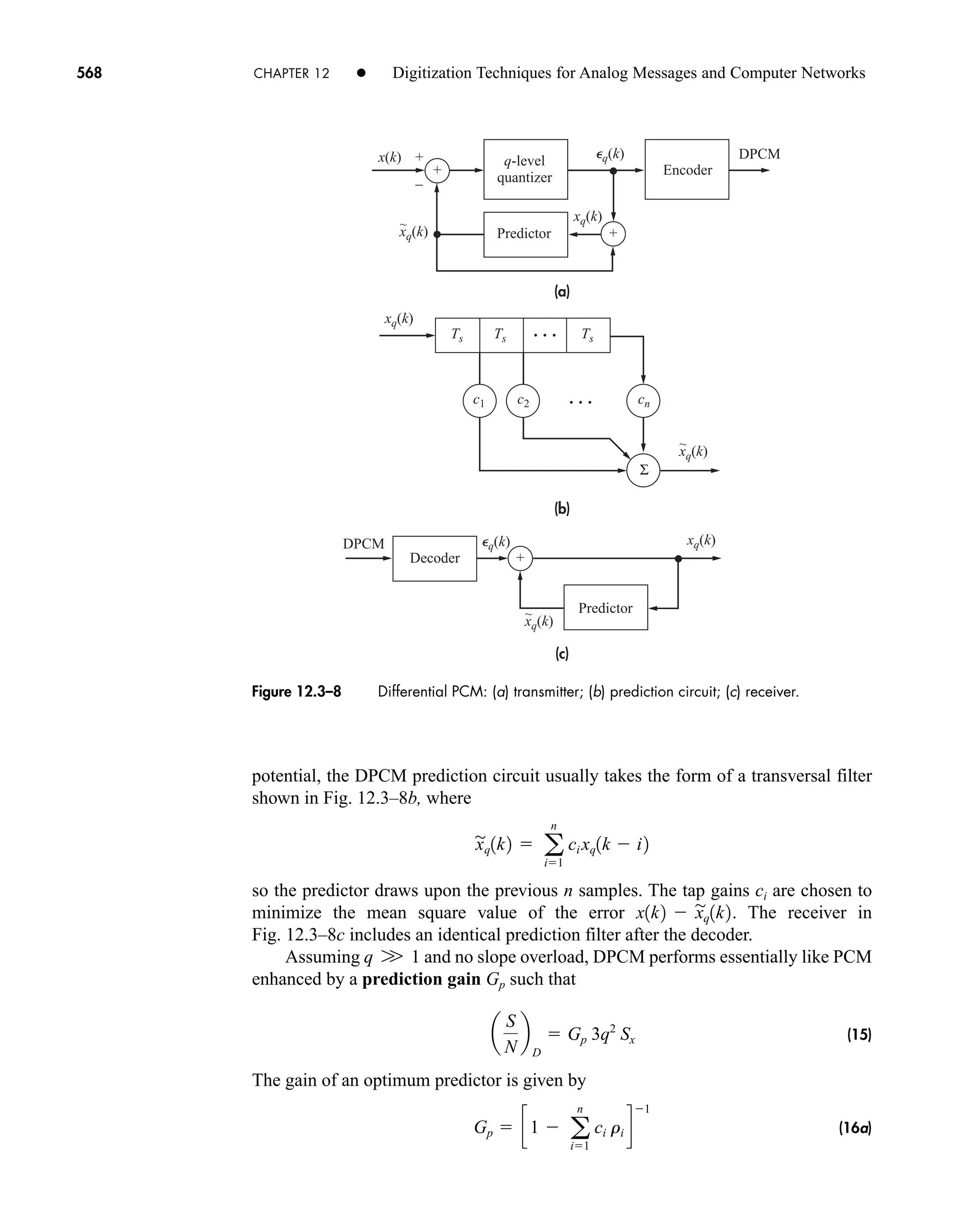

fs

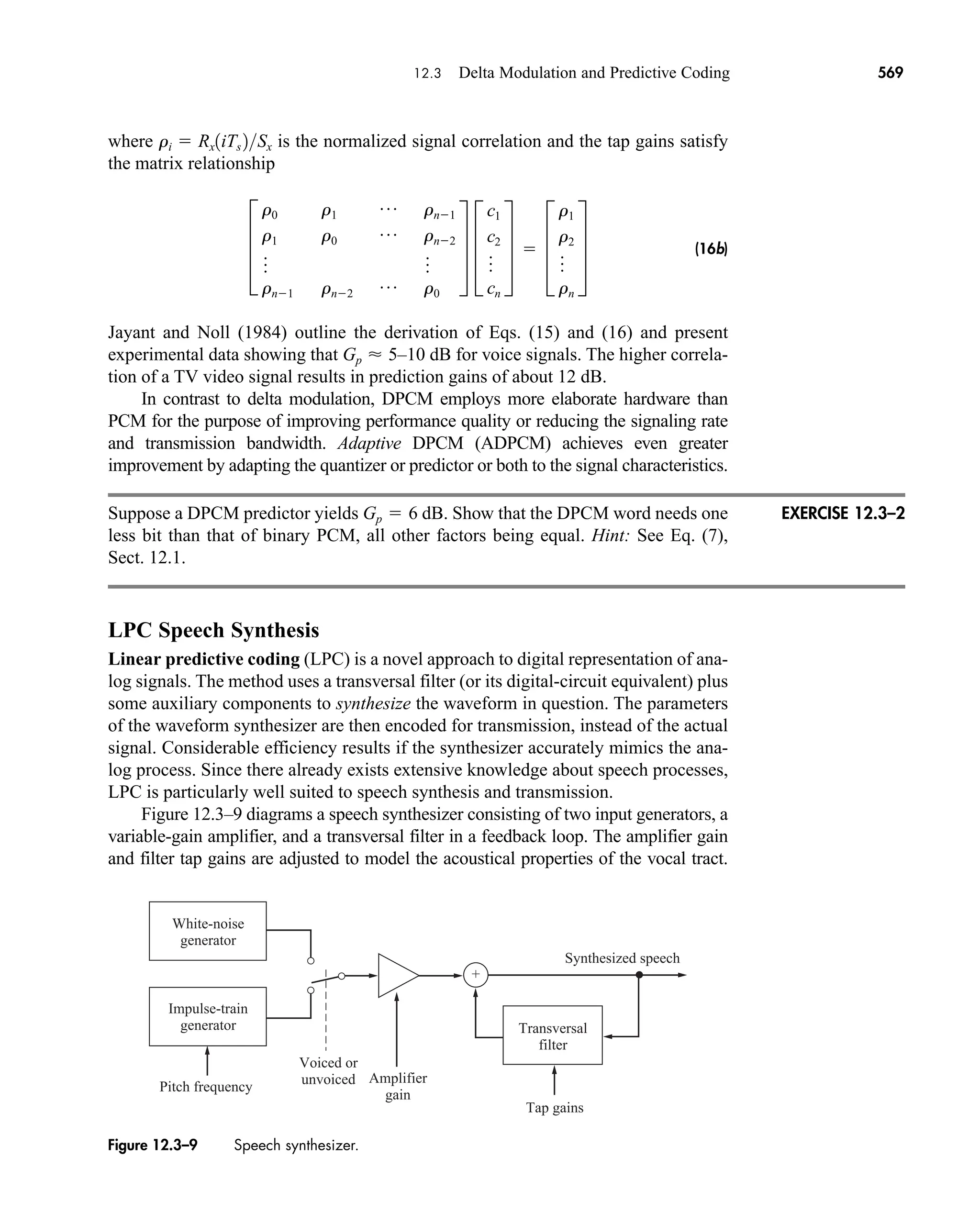

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-103-2048.jpg)

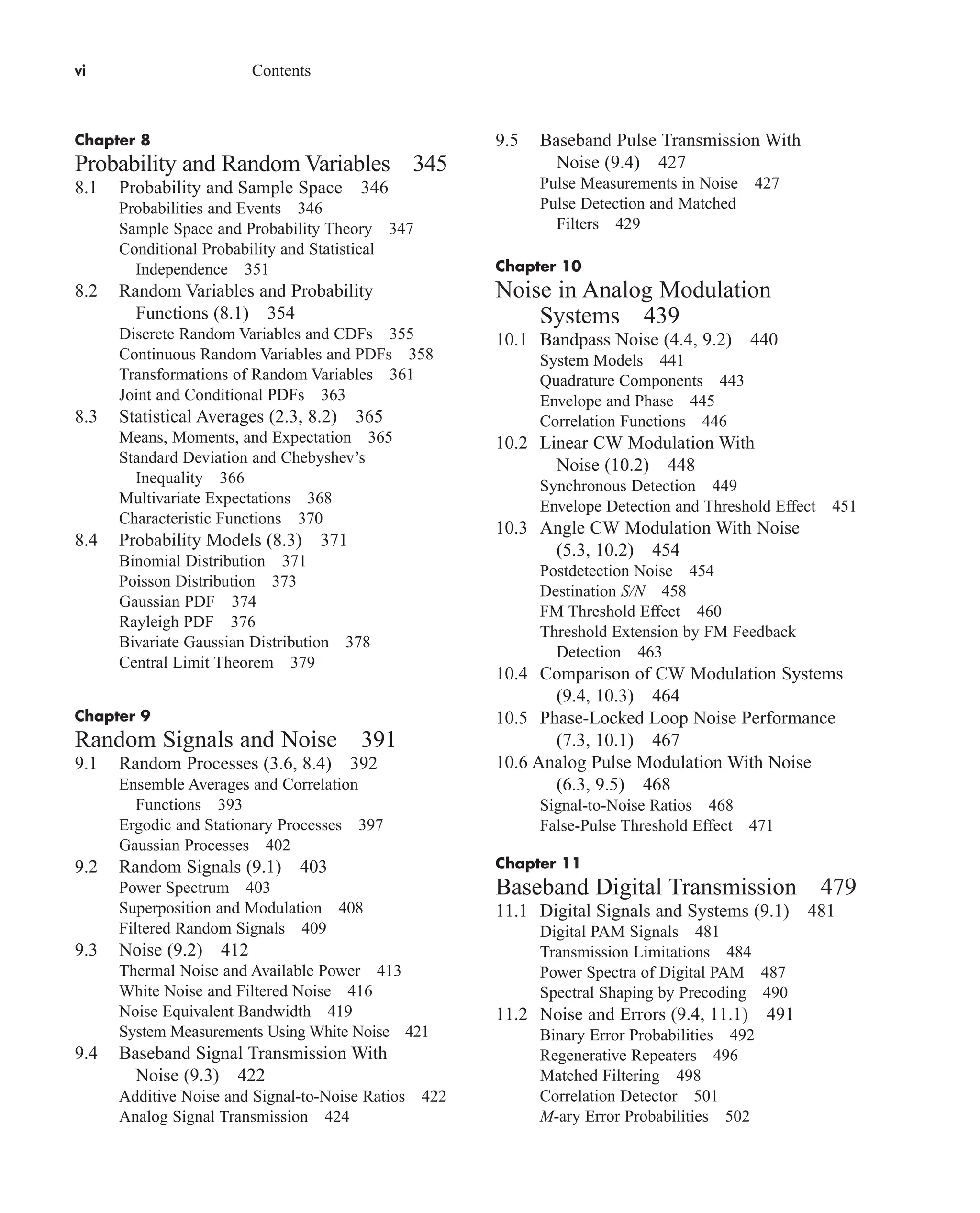

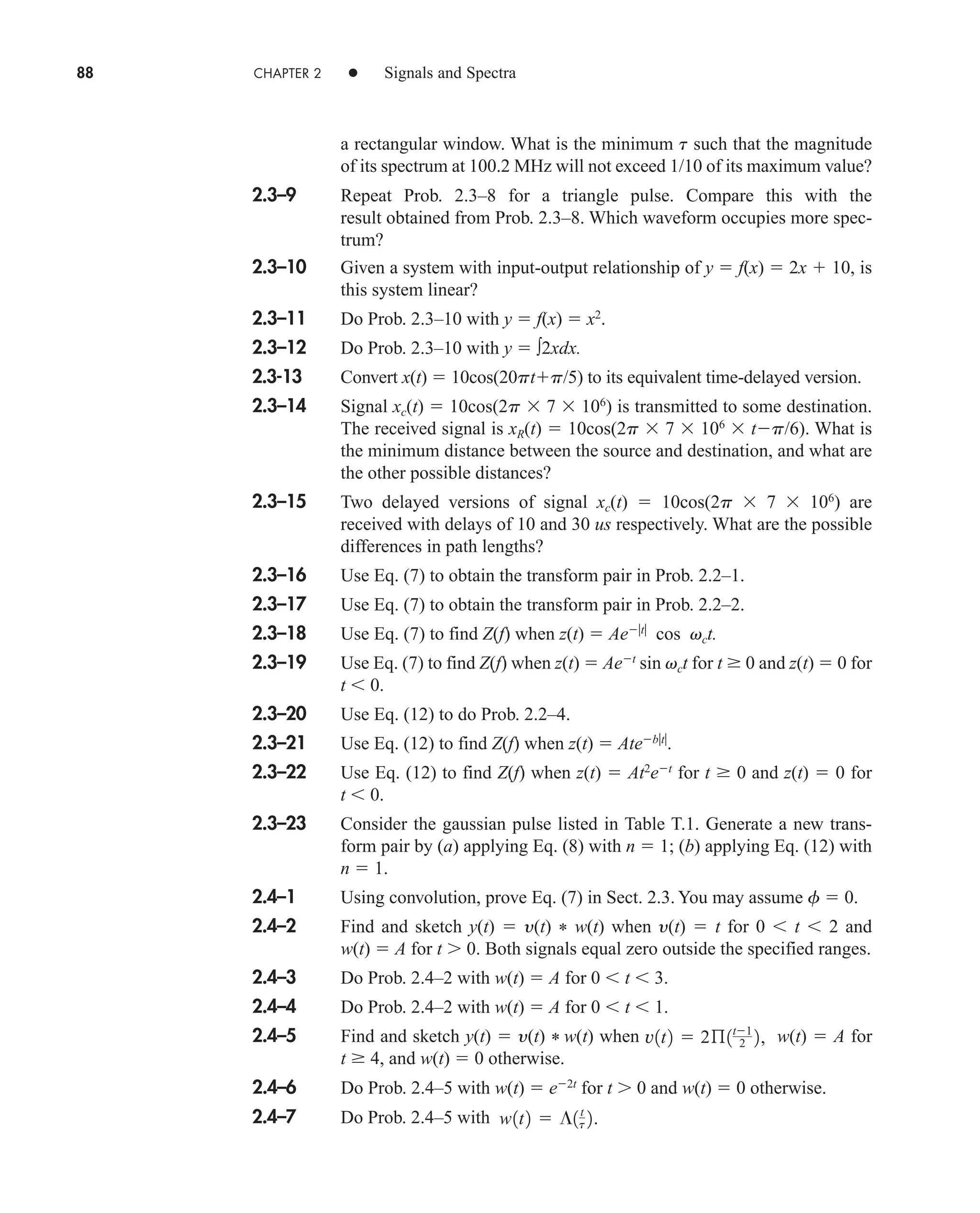

![2.6 Discrete Time Signals and the Discrete Fourier Transform 83

Note that k to (k 1) corresponds to a 1-second interval and n to (n 1) corre-

sponds to a 1/64 Hz interval. Therefore, the graphs of x(k) and X(n) span 64 sec-

onds and 64 Hz respectively.

Derive Eq. (2). Assume the signal was sampled by an impulse train.

Convolution Using the DFT

Just as with the continuous-time system, the output of a discrete-time system is the

linear convolution of the input with the system’s impulse response system, or simply

(7)

where the lengths of x(k) and h(k) are bounded by N1 and N2 respectively, the length of

y(k) is bounded by N (N1 N2 1), y(k) and x(k) are the sampled versions of y(t)

and x(t) respectively, and * denotes the linear convolution operator. The system’s

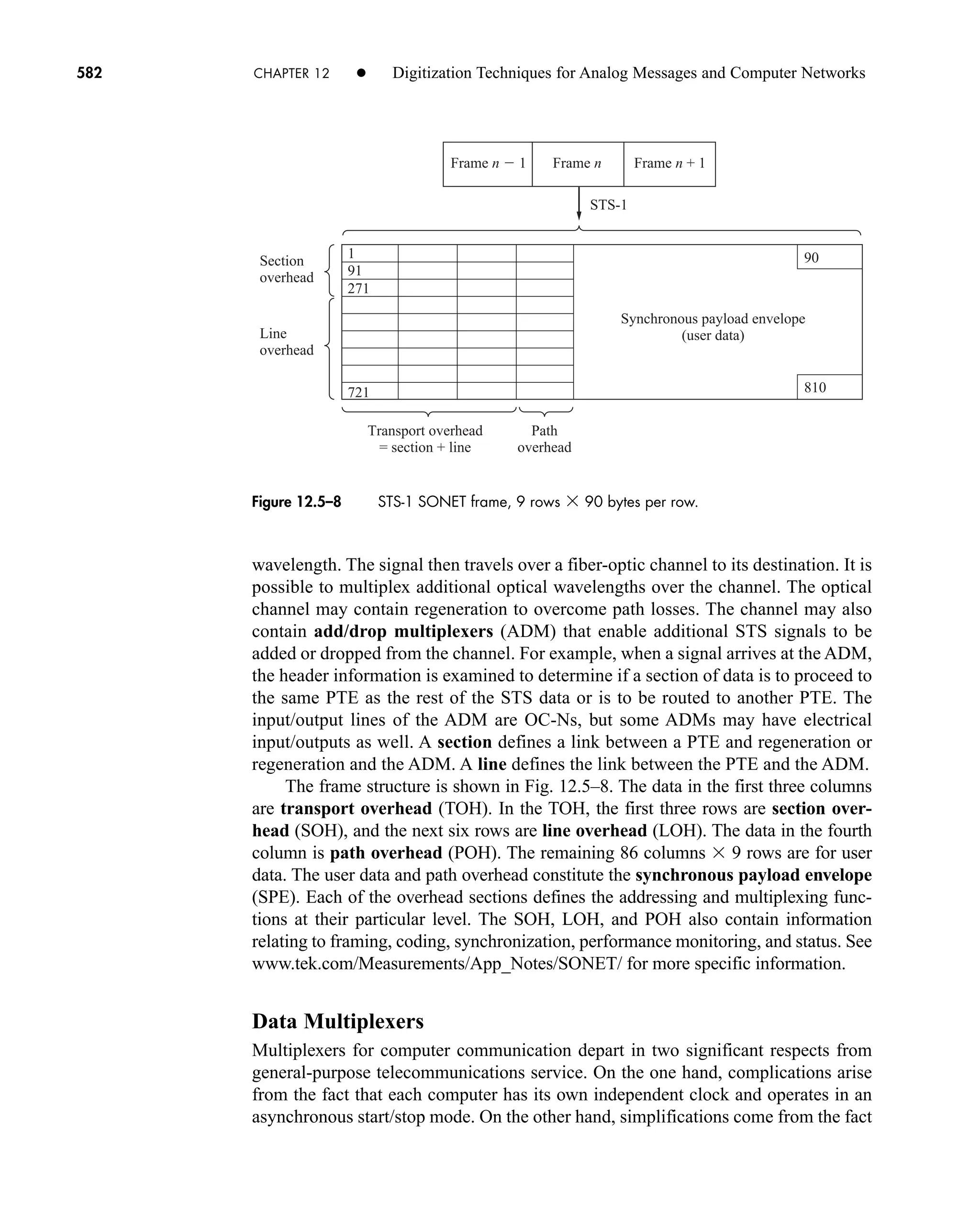

discrete-time impulse response function, h(k), is approximately equal to its analog

counterpart, h(t).†

However, for reasons of brevity, we will not discuss under what con-

ditions they are closely equal. Note that we still have the DFT pair of

where H(k) is discrete system response.

h1k2 4 H1k2

y1k2 x1k2 * h1k2 a

N

l0

x1l2h1k l2

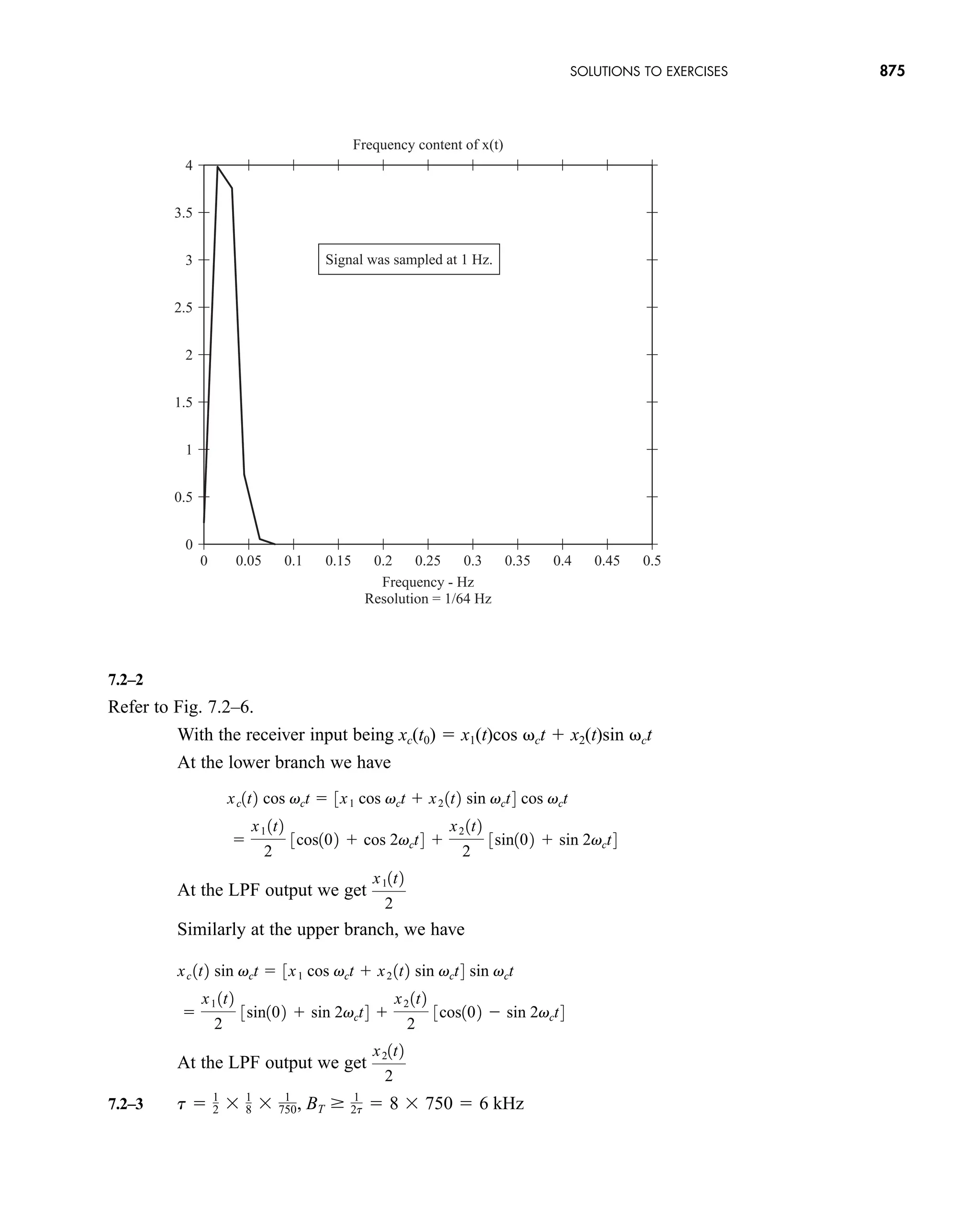

Figure 2.6-2 Monocycle and its DFT: (a) Monocycle x(k) with Ts 1 s.; (b) Re[X(n)];

(c) Im[X(n)]; (d) Puu(n) |X(n)|2

.

x(k)

XR(n)

XI(n)

Puu(n)

n

n

n

n

k

(a)

(b)

(c)

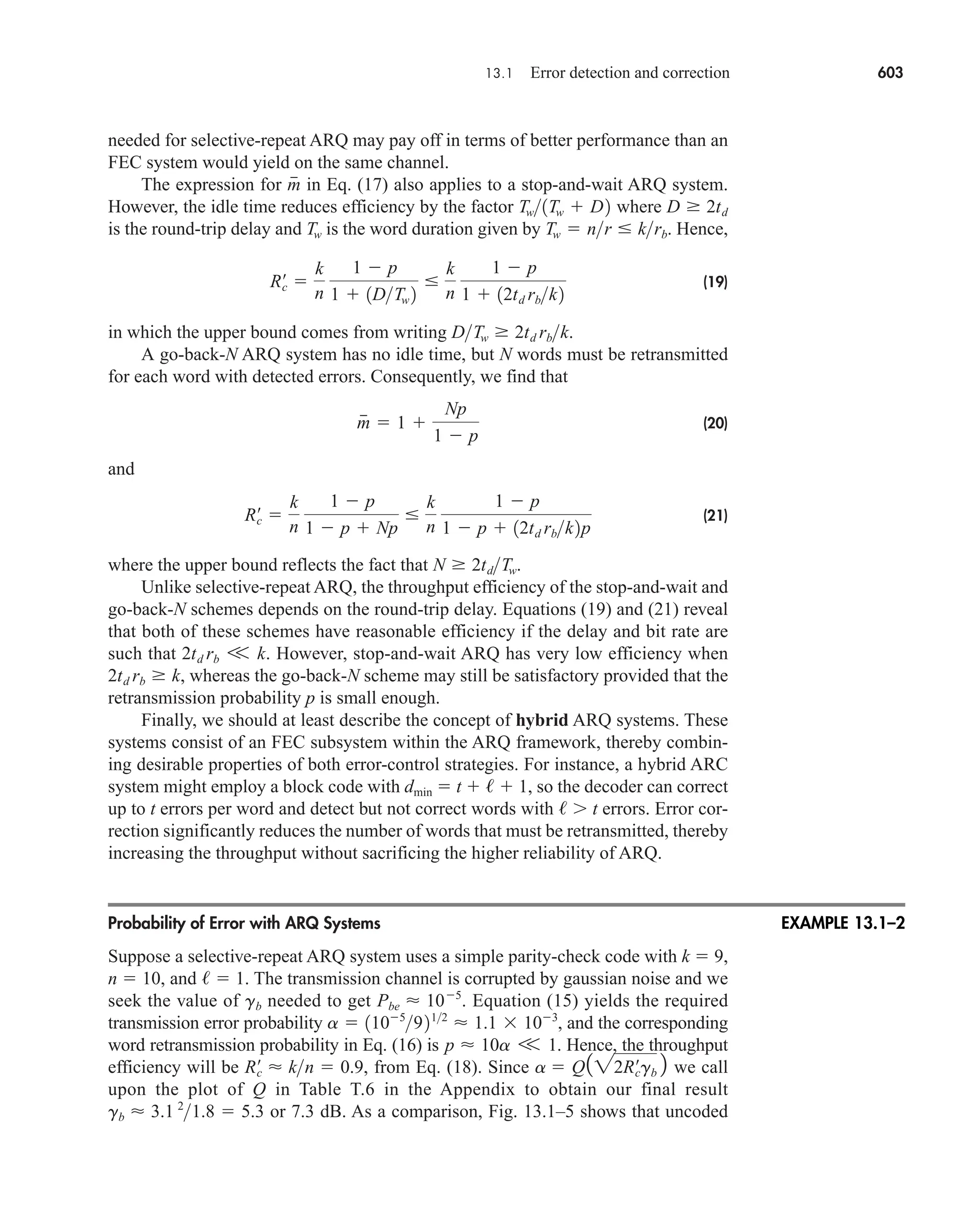

(d)

1

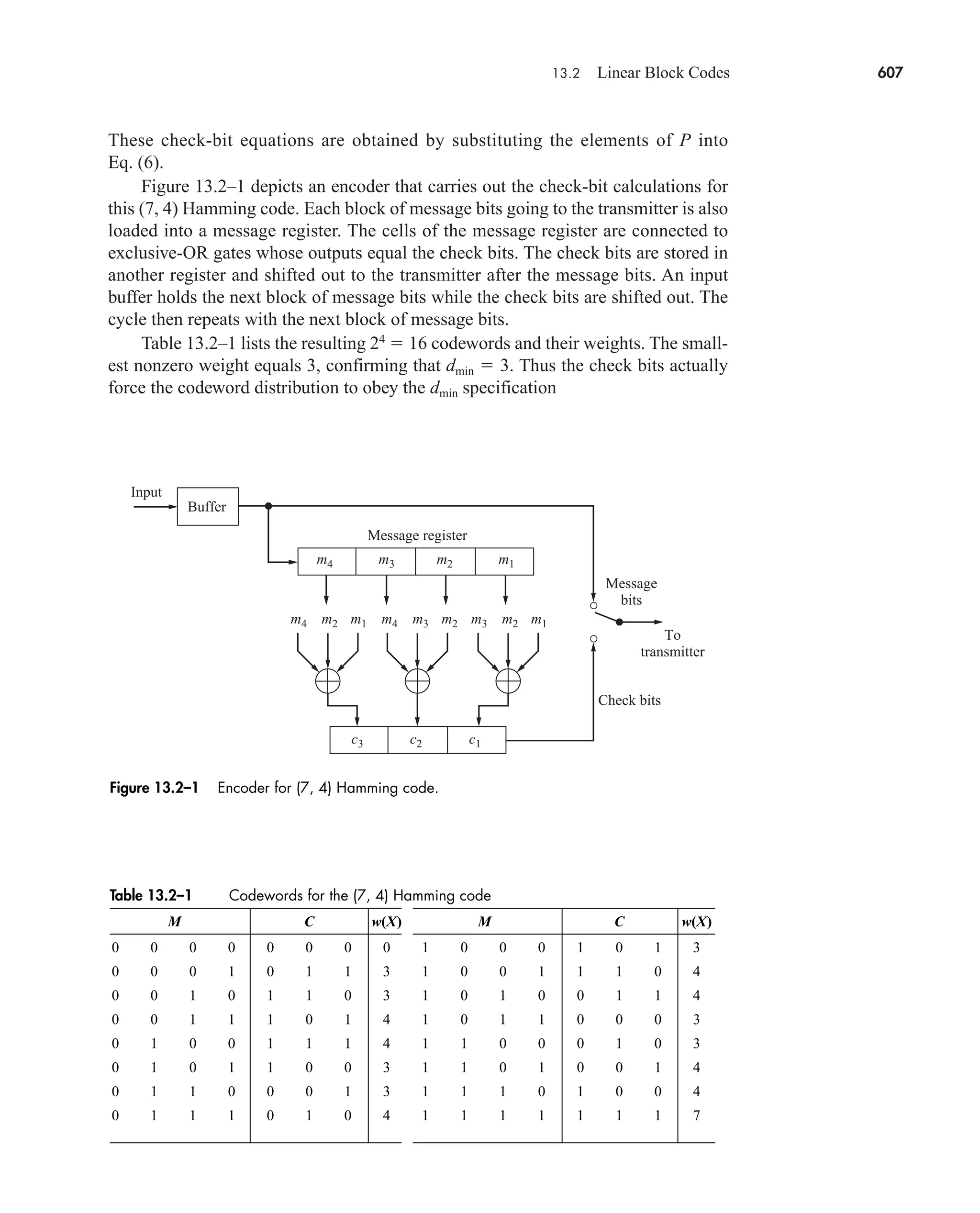

0

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

−1

5

0

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

−5

20

0

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

−20

4

2

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

0

EXERCISE 2.6–1

†

Function h(k) ≅ h(t) if fs Nyquist rate. See Ludeman (1986) for more information.

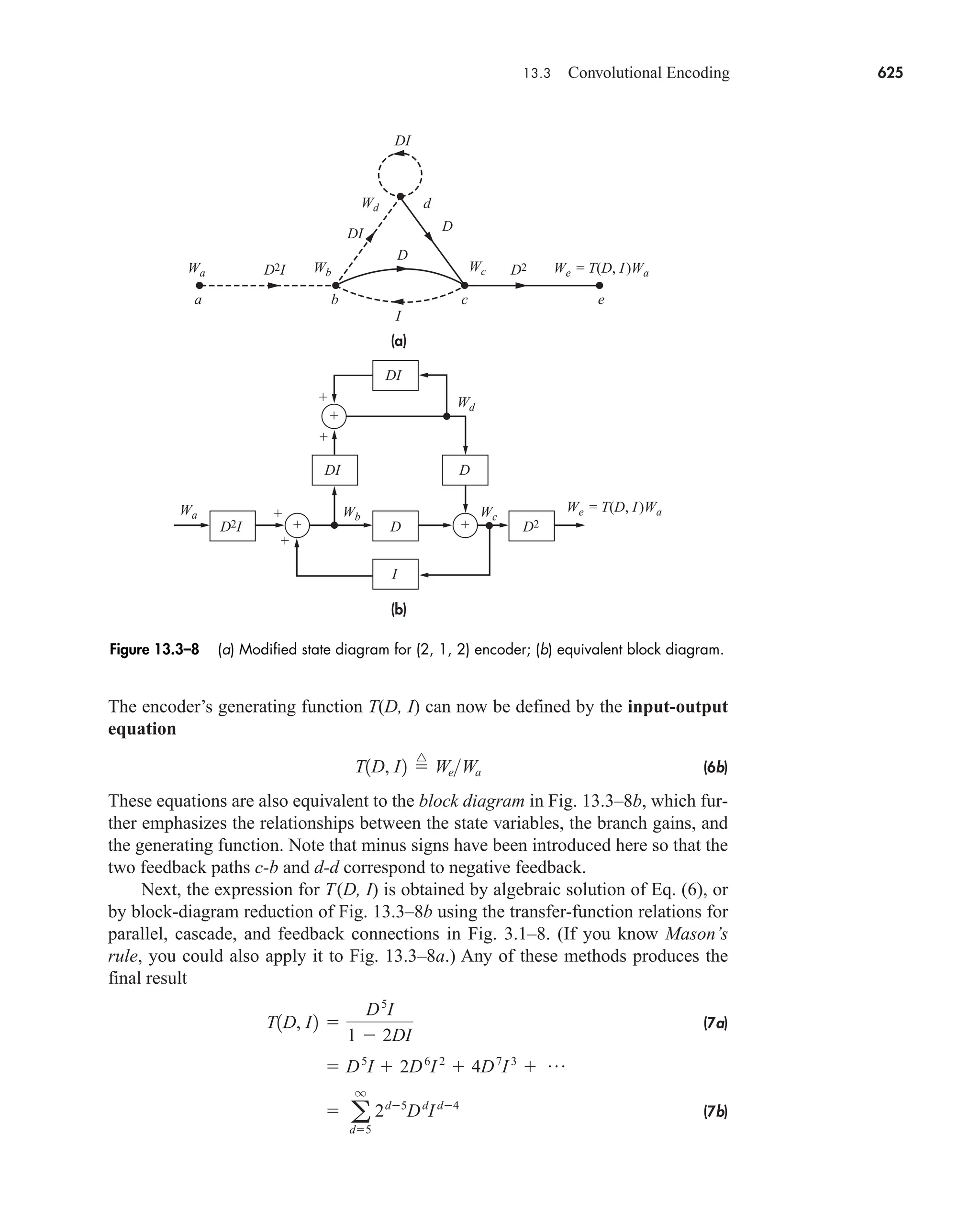

W

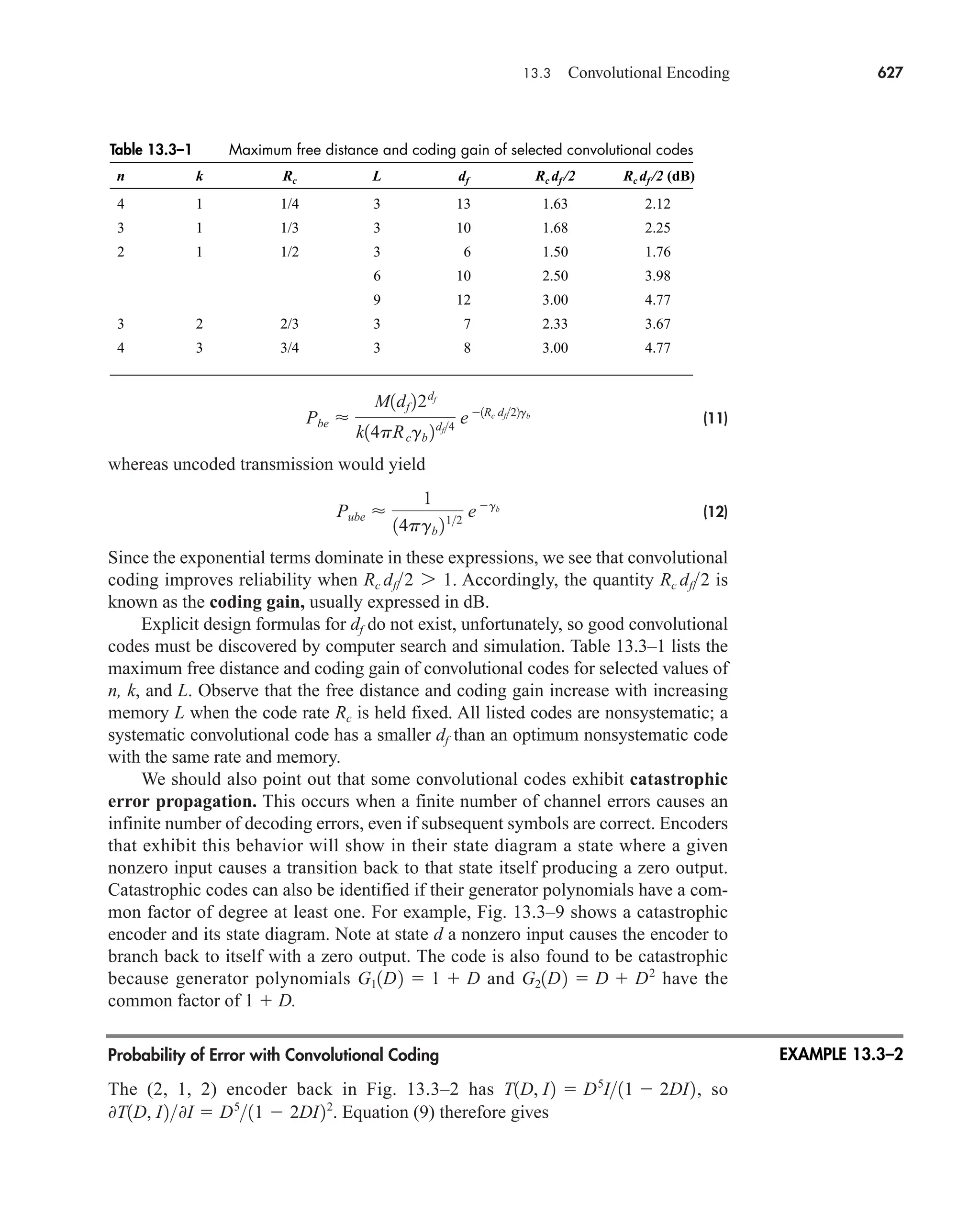

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 83](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-105-2048.jpg)

![84 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

If

then we have

(8)

where ⊗ denotes circular convolution. Circular convolution is similar to linear con-

volution, except both functions must be the same length, and the resultant function’s

length can be less than the bound of N1 N2 1. Furthermore, while the operation

of linear convolution adds to the resultant sequence’s length, with circular convolu-

tion, the new terms will circulate back to the beginning of the sequence.

It is advantageous to use specialized DFT hardware to perform the computa-

tions, particularly as we will see in Sect. 14.5. If we are willing to constrain the

lengths of N1 N2 and N (2N1 1), then the linear convolution is equal to the cir-

cular convolution,

(9a)

[9b]

(9c)

and

(9d)

The lengths of x1(k) and x2(k) can be made equal by appending zeros to the sequence

with the shorter length. Thus, just as the CFT replaces convolution in continuous-

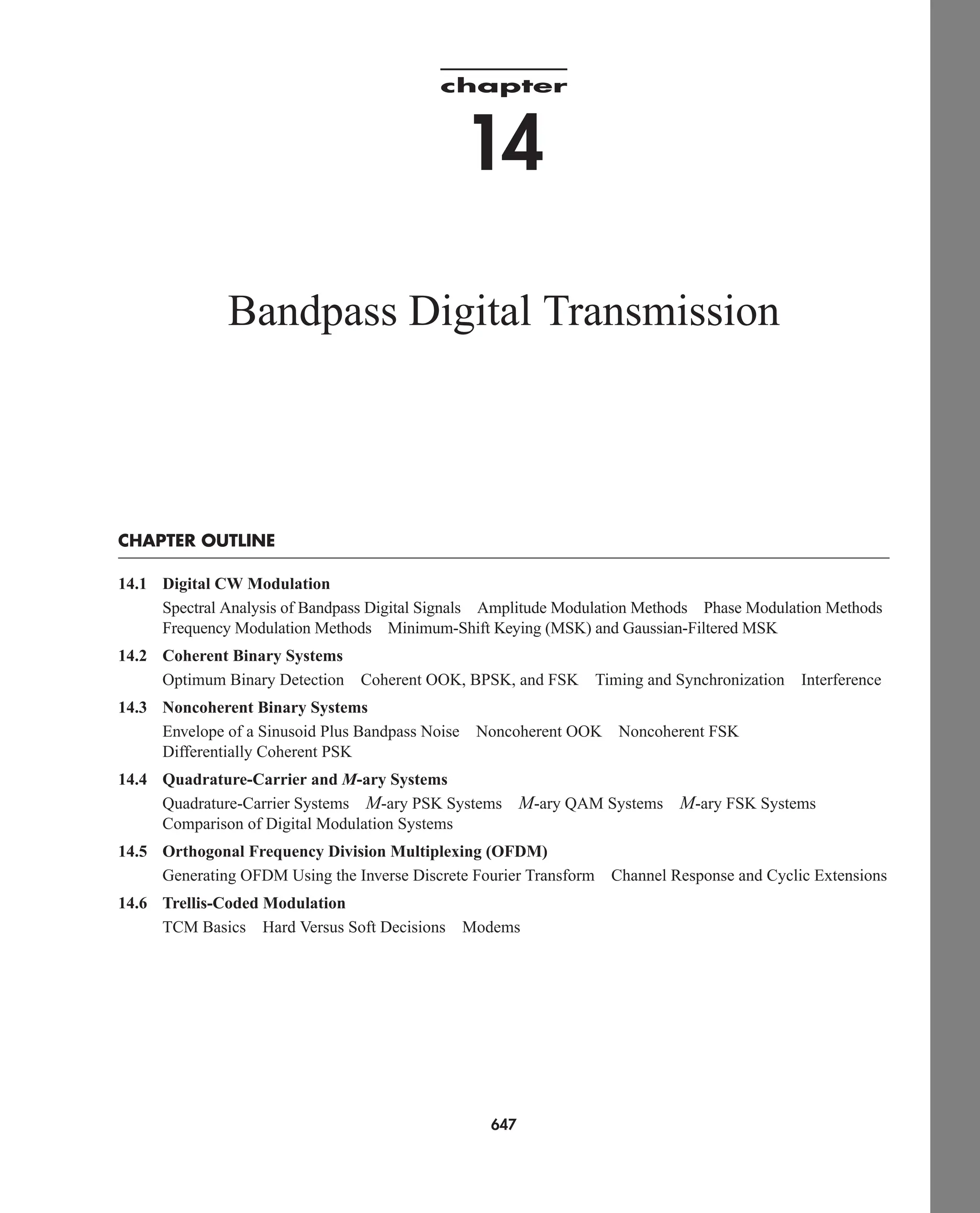

time systems, so can the DFT be used to replace linear convolution for discrete-time

systems. For more information on the the DFT and circular convolution, see Oppen-

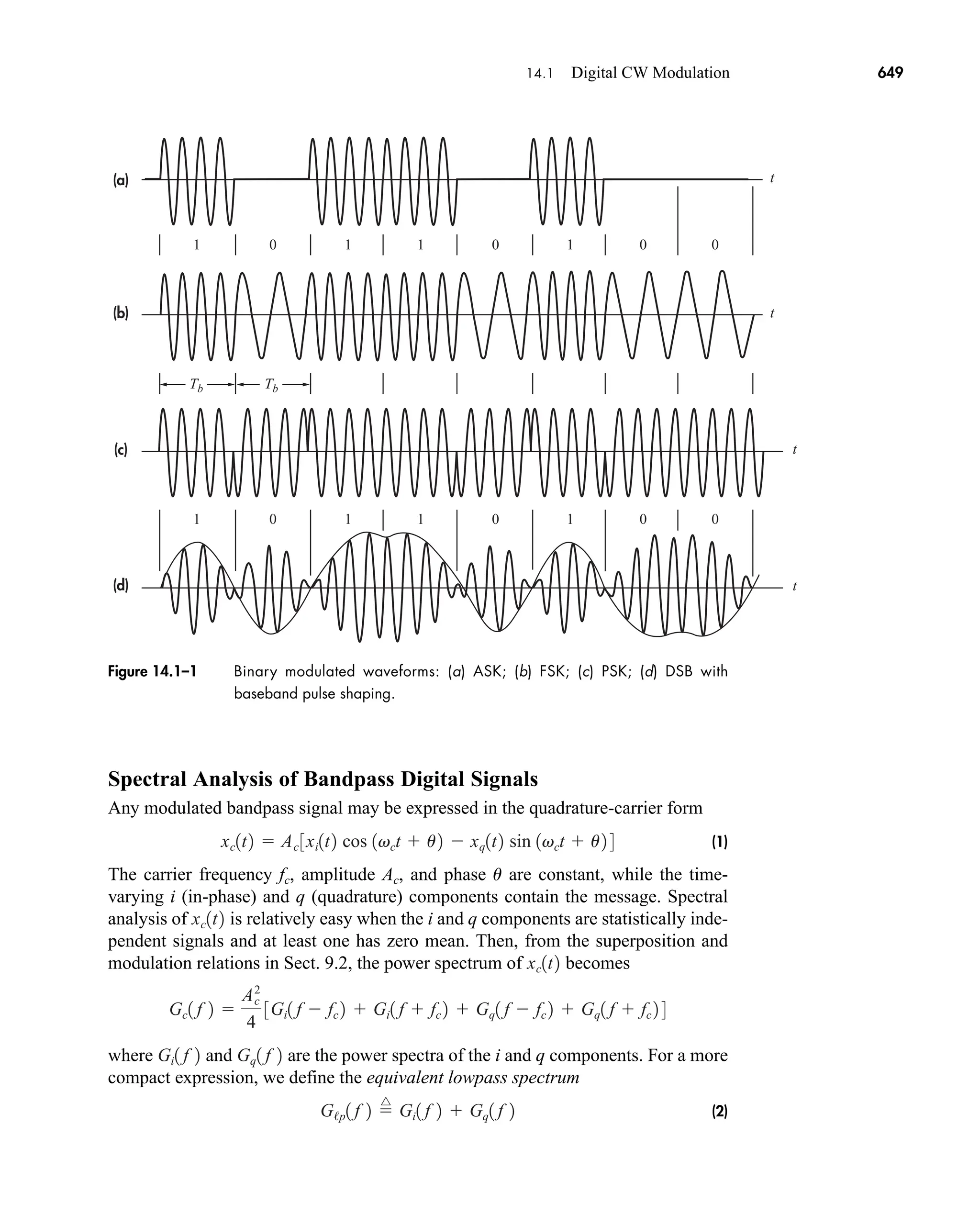

heim, Schafer, and Buck (1999).

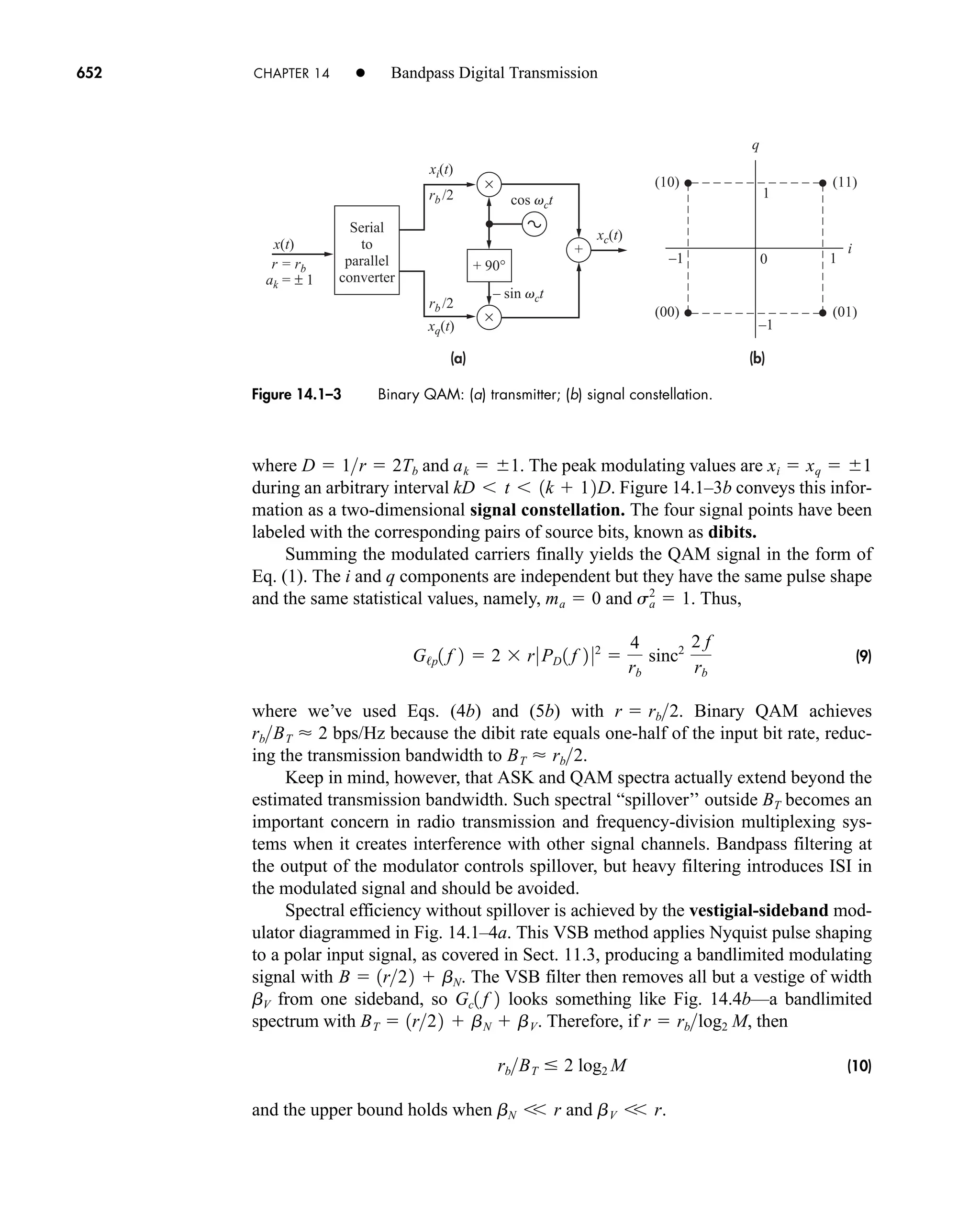

2.7 QUESTIONS AND PROBLEMS

Questions

1. Why would periodic signals be easier to intercept than nonperiodic ones?

2. Both the H(f) sinc(ft) and H(f) sinc2

(ft) have low-pass-frequency responses,

and thus could be used to reconstruct a sampled signal. What is their equivalent

operation in the time domain?

3. You have designed a noncommunications product that emits radio frequency

(RF) interference that exceeds the maximum limits set by the FCC. What signal

shapes would most likely be the culprit?

y1k2 IDFT3Y1n2 4

Y1k2 DFT3x11n2 z x21n2 4

Y1n2 DFT3x11k2 4 DFT3x21k2 4

y1k2 x11k2 * x21k2 x11k2 z x21k2

x11k2 z x21k2 4 X11n2X21n2

X11n2 DFT3x1 1k2 4 and X2 1n2 DFT3x21k2 4

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 84](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-106-2048.jpg)

![86 CHAPTER 2 • Signals and Spectra

2.1–6 Do Prob. 2.1–5 with y(t) A sin(2pt/T0) for t T0/2.

2.1–7‡

Consider a periodic signal with the half-wave symmetry property

y(tT0/2) y(t) , so the second half of any period looks like the first

half inverted. Show that cn 0 for all even harmonics.

2.1–8 How many harmonic terms are required in the Fourier series of a peri-

odic square wave with 50 percent duty cycle and amplitude A to rep-

resent 99 percent of its power?

2.1–9* Use Parseval’s power theorem to calculate the average power in the rec-

tangular pulse train with t/T0 1/4 if all frequencies above f 1/t are

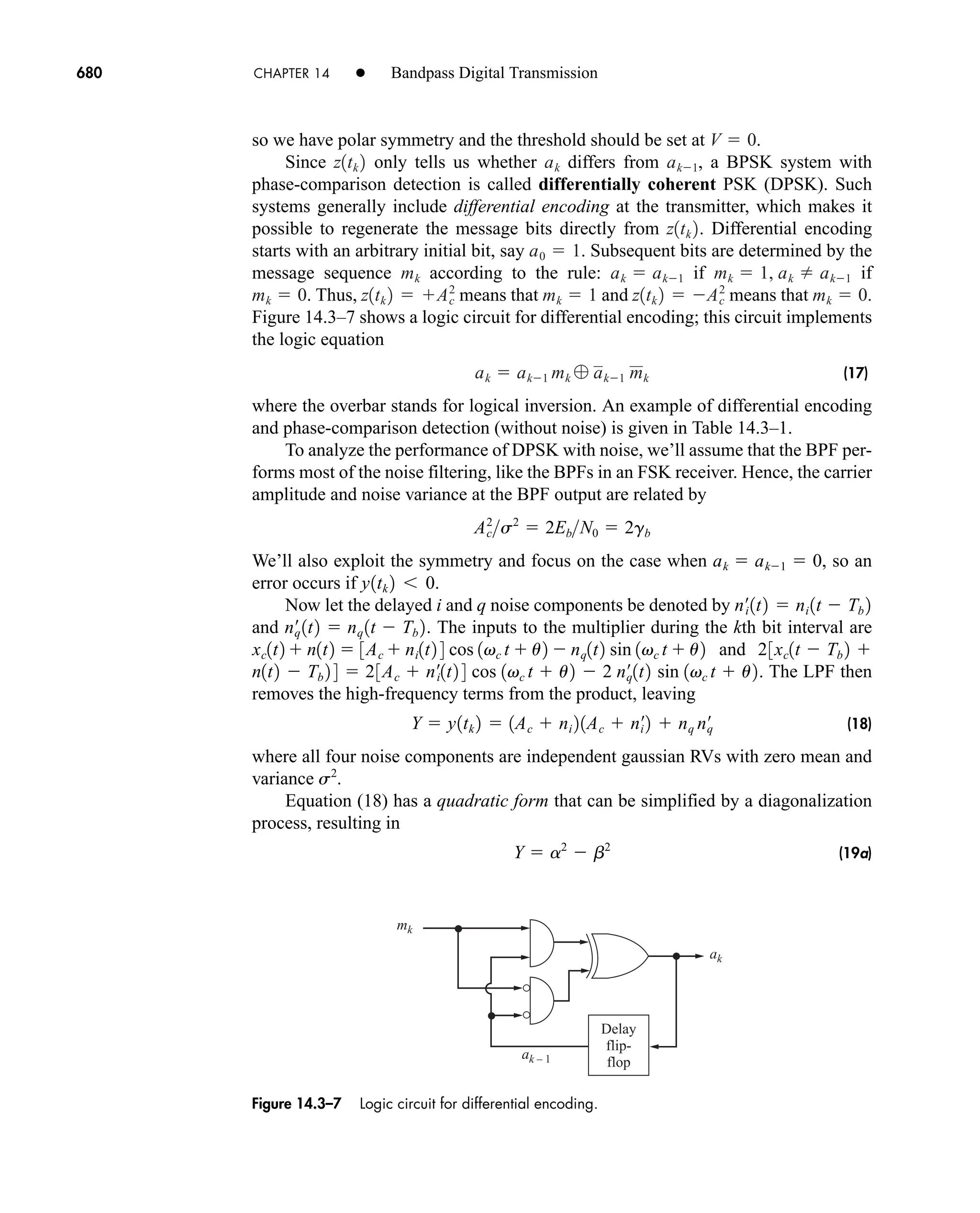

removed. Repeat for the cases where all frequencies above f 2/t and

f 1/2t are removed.

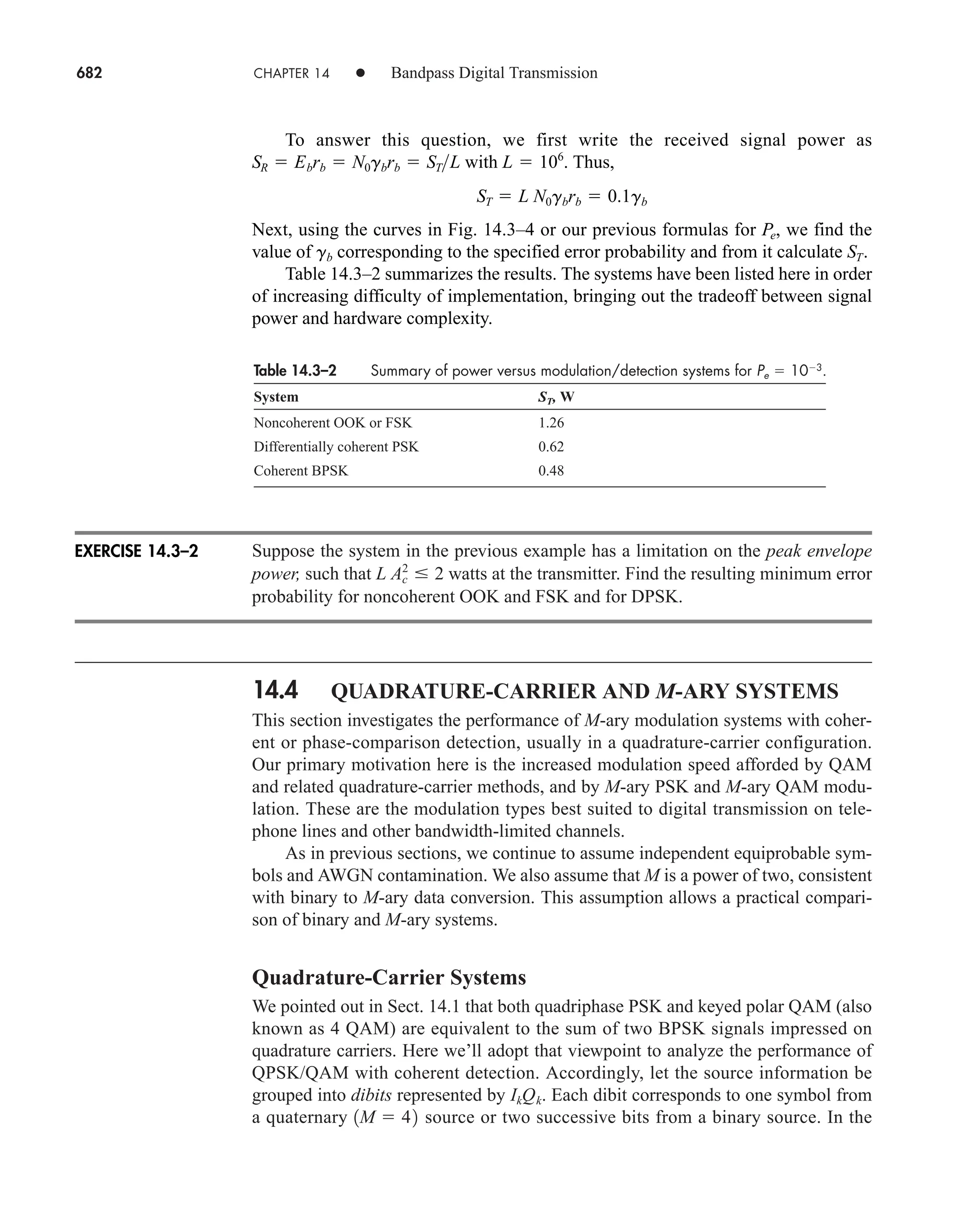

2.1–10 Let y(t) be the triangular wave with even symmetry listed in Table T.2,

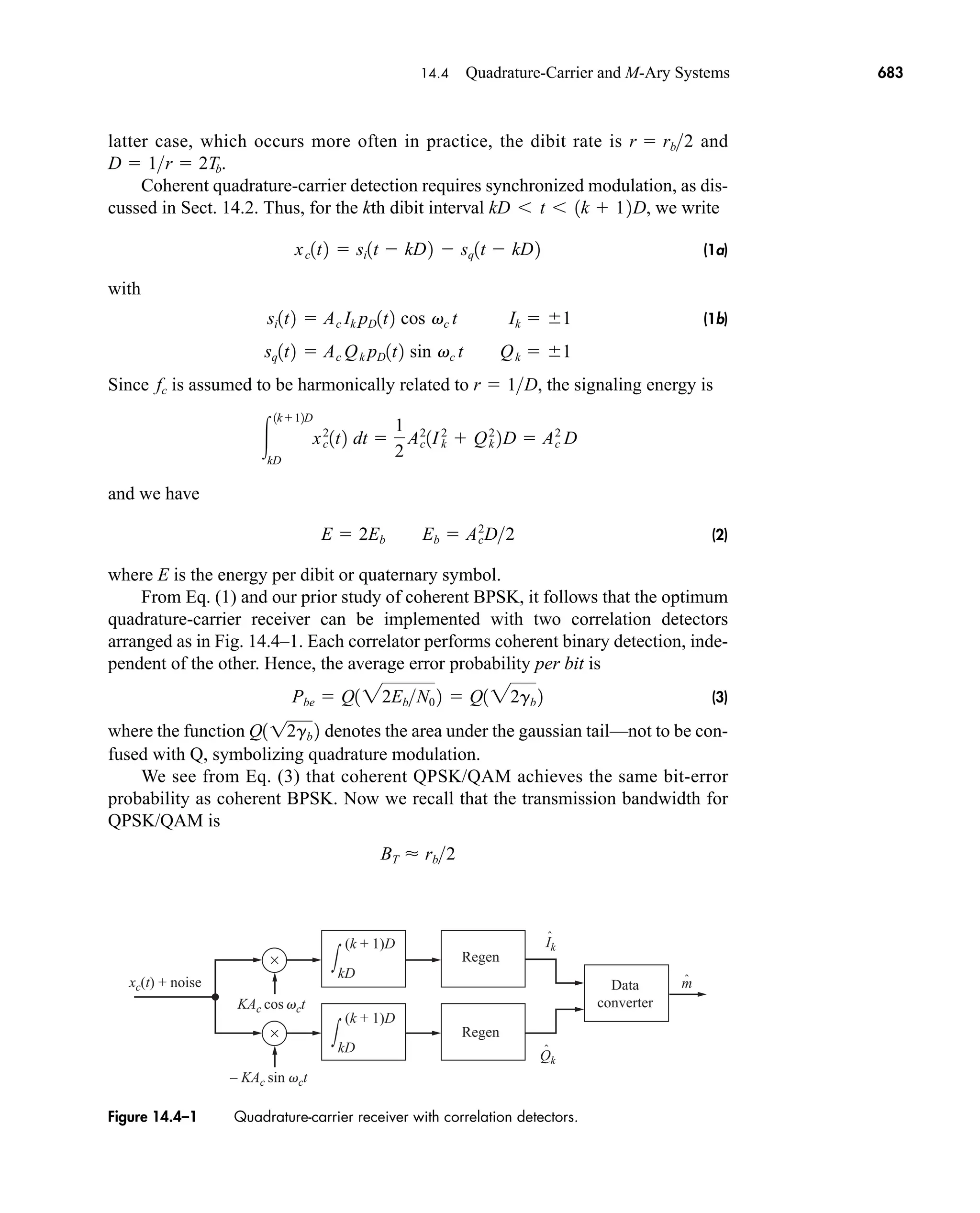

and let y(t) be the approximating obtained with the first three nonzero

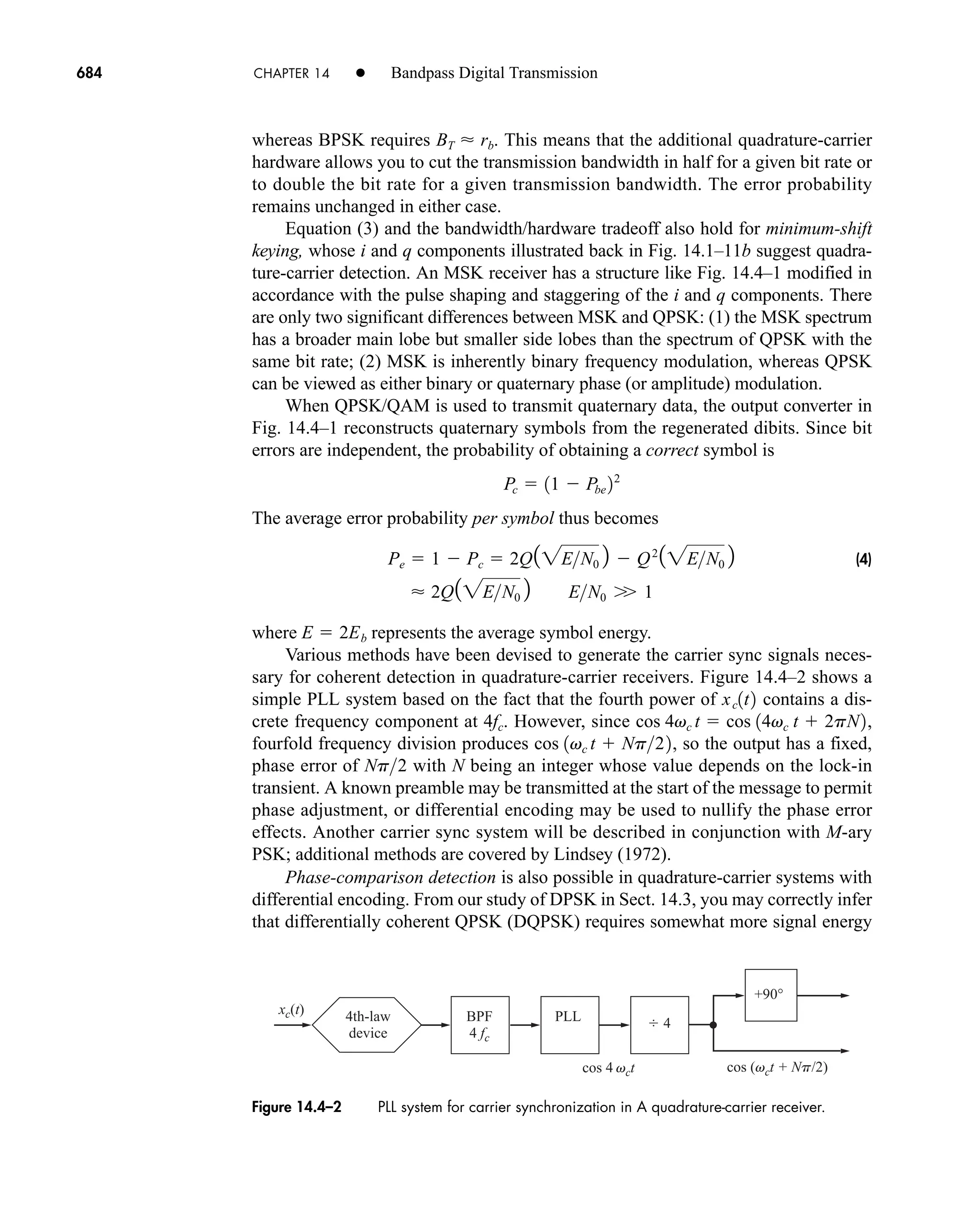

terms of the trigonometric Fourier series. (a) What percentage of the

total signal power is contained in y(t)? (b) Sketch y(t) for t T0/2.

2.1–11 Do Prob. 2.1–10 for the square wave in Table T.2.

2.1–12‡

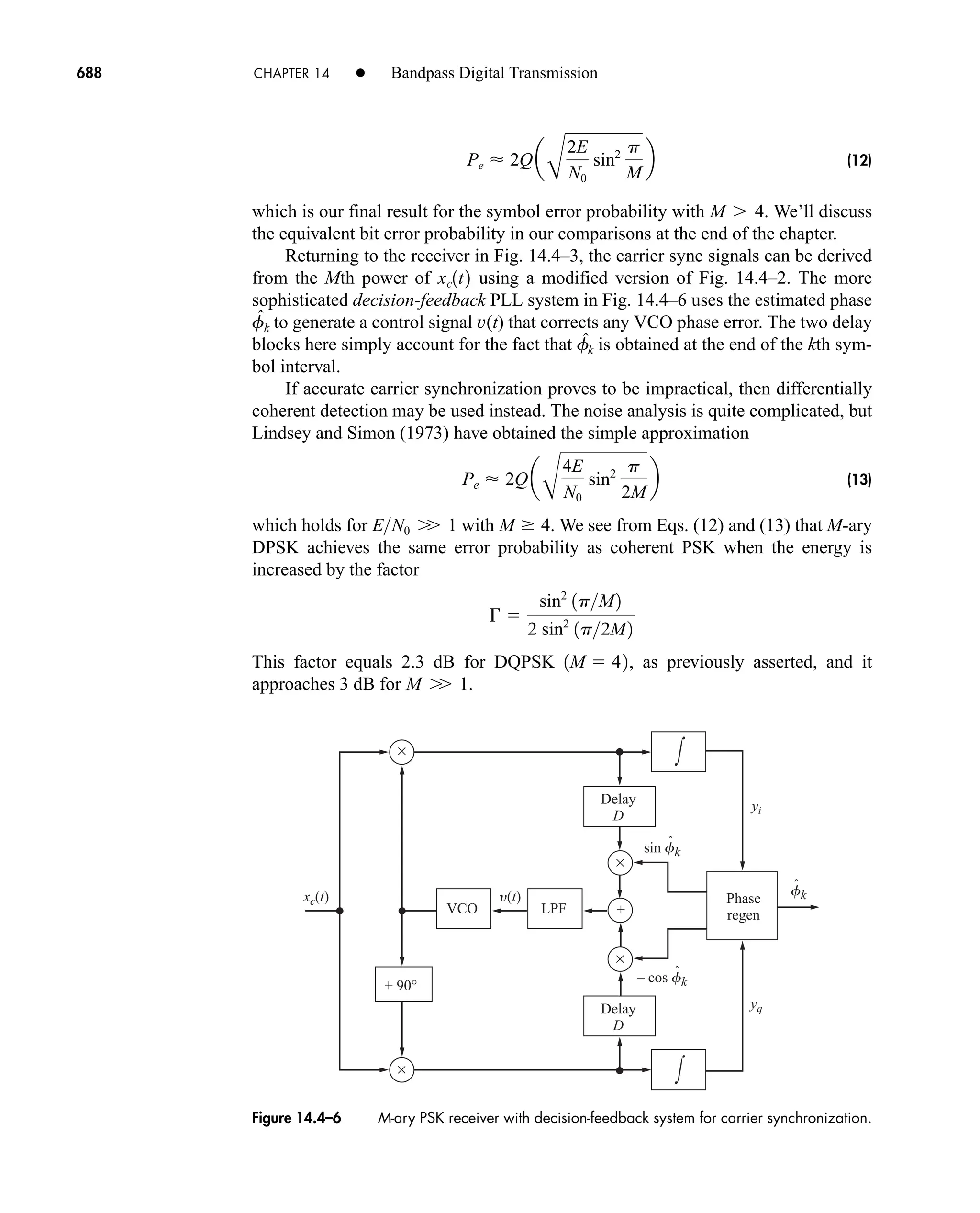

Calculate P for the sawtooth wave listed in Table T.2. Then apply Parse-

val’s power theorem to show that the infinite sum 1/12

1/22

1/32

. . . equals p2

/6.

2.1–13‡

Calculate P for the triangular wave listed in Table T.2. Then apply Parse-

val’s power theorem to show that the infinite sum 1/14

1/34

1/54

. . . equals p4

/96.

2.2–1 Consider the cosine pulse y(t) Acos(pt/t)Π(t/t). Show that

V(f) (At/2)[sinc(ft 1/2) sinc(ft 1/2)]. Then sketch and label

V(f) for f 0 to verify reciprocal spreading.

2.2–2 Consider the sine pulse y(t) Asin(2pt/t)Π(t/t). Show that V(f)

j(At/2)[sinc(ft 1) sinc(ft 1)]. Then sketch and label V(f) for

f 0 to verify reciprocal spreading.

2.2–3 Find V(f) when y(t) (A At/t)Π(t/2t). Express your result in terms

of the sinc function.

2.2–4* Find V(f) when y(t) (At/t)Π(t/2t). Express your result in terms of the

sinc function.

2.2–5 Given y(t) Π(t/t) with t 1 ms. Determine f0 such that

for all f f0

2.2–6 Repeat Prob. 2.2–5 for y(t) Λ (t/t).

V1f2 6

1

30

V102

*

Indicates answer given in the back of the book.

car80407_ch02_027-090.qxd 12/8/08 11:04 PM Page 86](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-108-2048.jpg)

![3.1 Response of LTI Systems 93

x(t) y(t)

Black box

Input Output

System

Figure 3.1–1 System showing external input and output.

Here we’re concerned with the special but important class of linear time-

invariant systems—or LTI systems for short. We’ll develop the input–output rela-

tionship in the time domain using the superposition integral and the system’s impulse

response. Then we’ll turn to frequency-domain analysis expressed in terms of the sys-

tem’s transfer function.

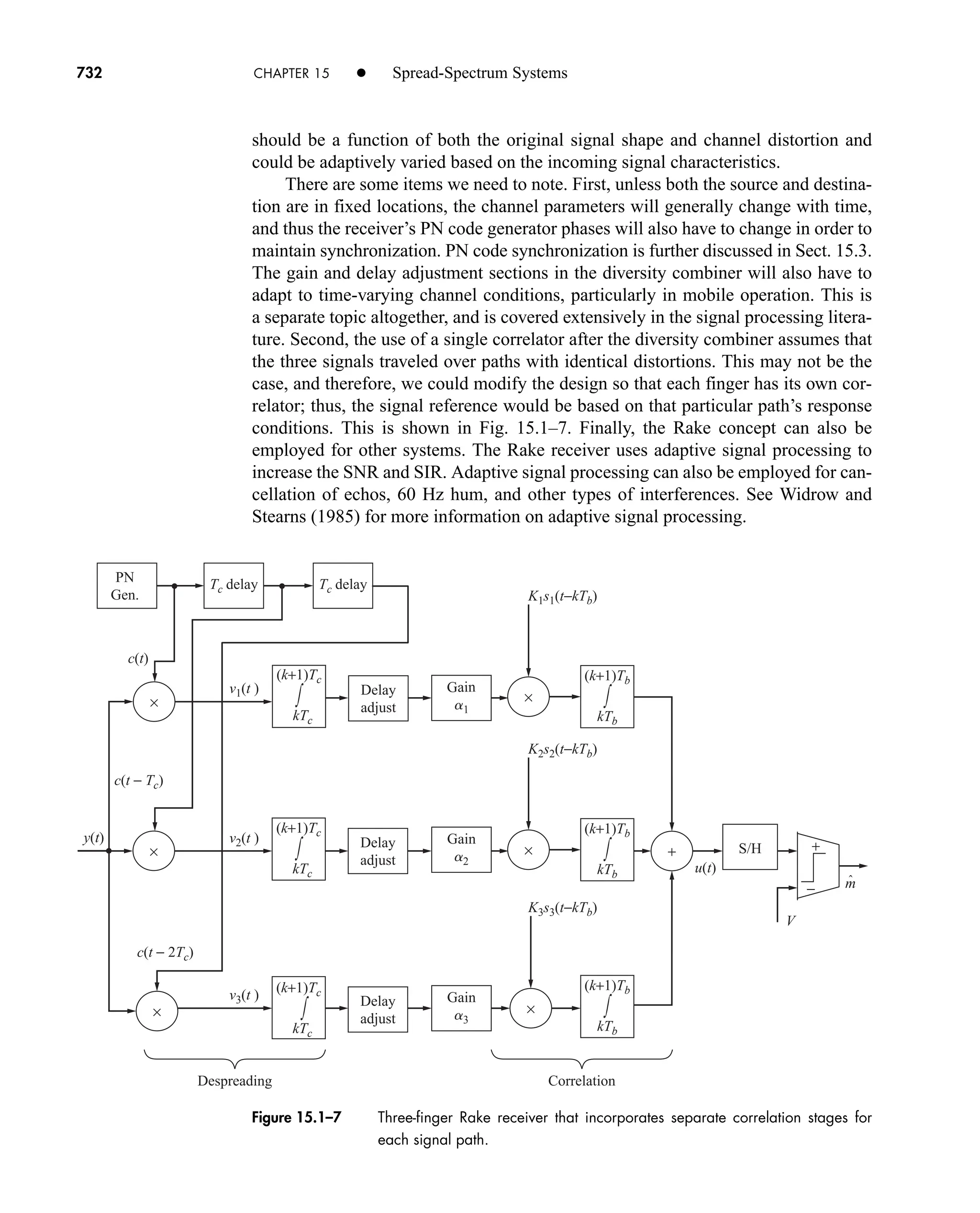

Impulse Response and the Superposition Integral

Let Fig. 3.1–1 be an LTI system having no internal stored energy at the time the input

x(t) is applied. The output y(t) is then the forced response due entirely to x(t), as rep-

resented by

(1)

where F[x(t)] stands for the functional relationship between input and output. The

linear property means that Eq. (1) obeys the principle of superposition. Thus, if

(2a)

where are constants, then

(2b)

The time-invariance property means that the system’s characteristics remain fixed

with time. Thus, a time-shifted input produces

(3)

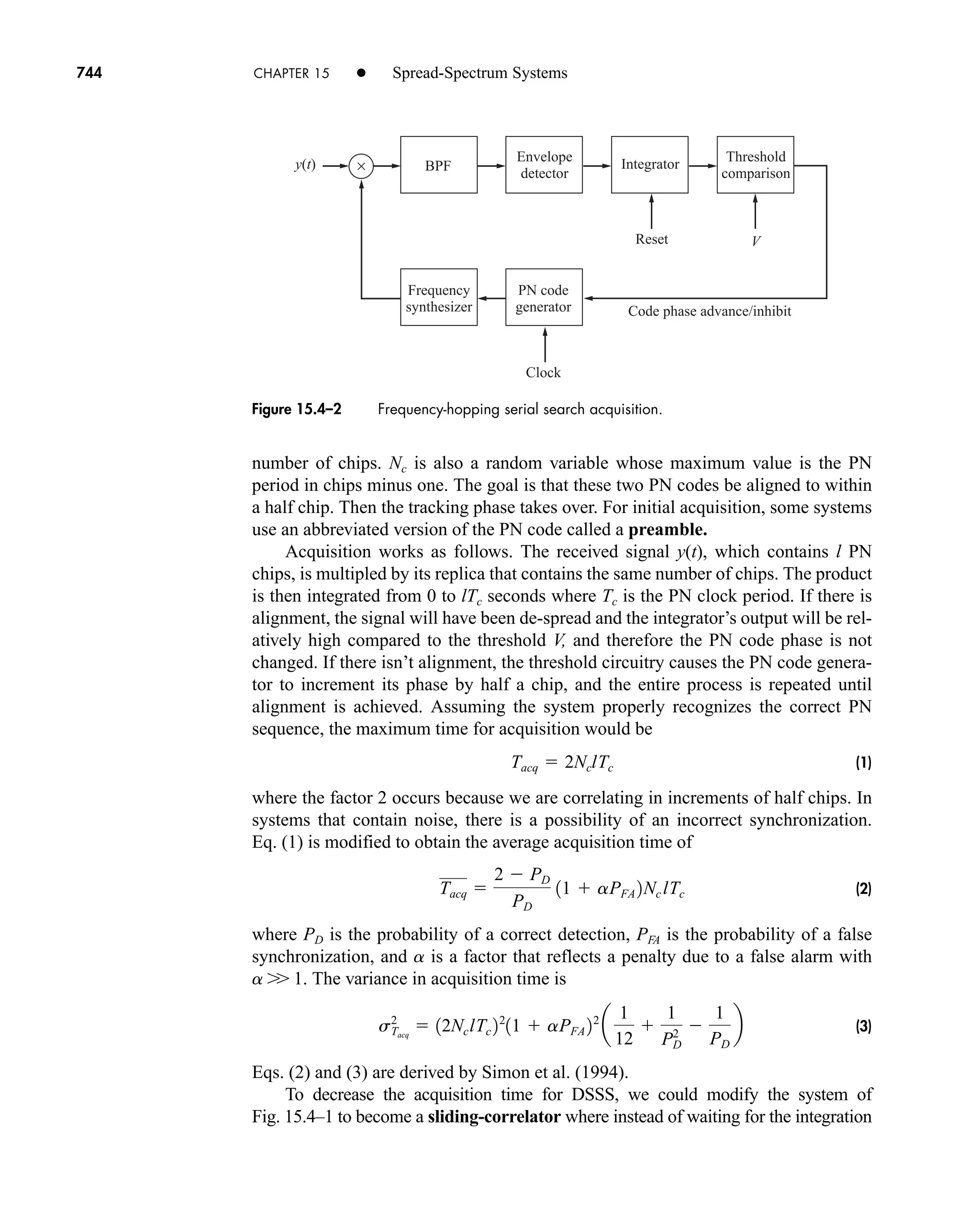

so the output is time-shifted but otherwise unchanged.

Most LTI systems consist entirely of lumped-parameter elements (such as resis-

tors capacitors, and inductors), as distinguished from elements with spatially distrib-

uted phenomena (such as transmission lines). Direct analysis of a lumped-parameter

system starting with the element equations leads to the input–output relation as a

linear differential equation in the form

(4)

an

dn

y1t2

dtn p a1

dy1t2

dt

a0 y1t2 bm

dm

x1t2

dtm p b1

dx1t2

dt

b0 x1t2

F3x1t td 2 4 y1t td 2

x1t td 2

y1t2 a

k

ak F3xk1t2 4

ak

x1t2 a

k

ak xk1t2

y1t2 F3x1t2 4

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 93](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-115-2048.jpg)

![94 CHAPTER 3 • Signal Transmission and Filtering

where the a’s and b’s are constant coefficients involving the element values. The

number of independent energy-storage elements determines the value of n, known as

the order of the system. Unfortunately, Eq. (4) doesn’t provide us with a direct ex-

pression for y(t).

To obtain an explicit input–output equation, we must first define the system’s

impulse response function

(5)

which equals the forced response when . Now any continuous input sig-

nal can be written as the convolution , so

in which the interchange of operations is allowed by virtue of the system’s linearity.

Now, from the time-invariance property, and hence

(6a)

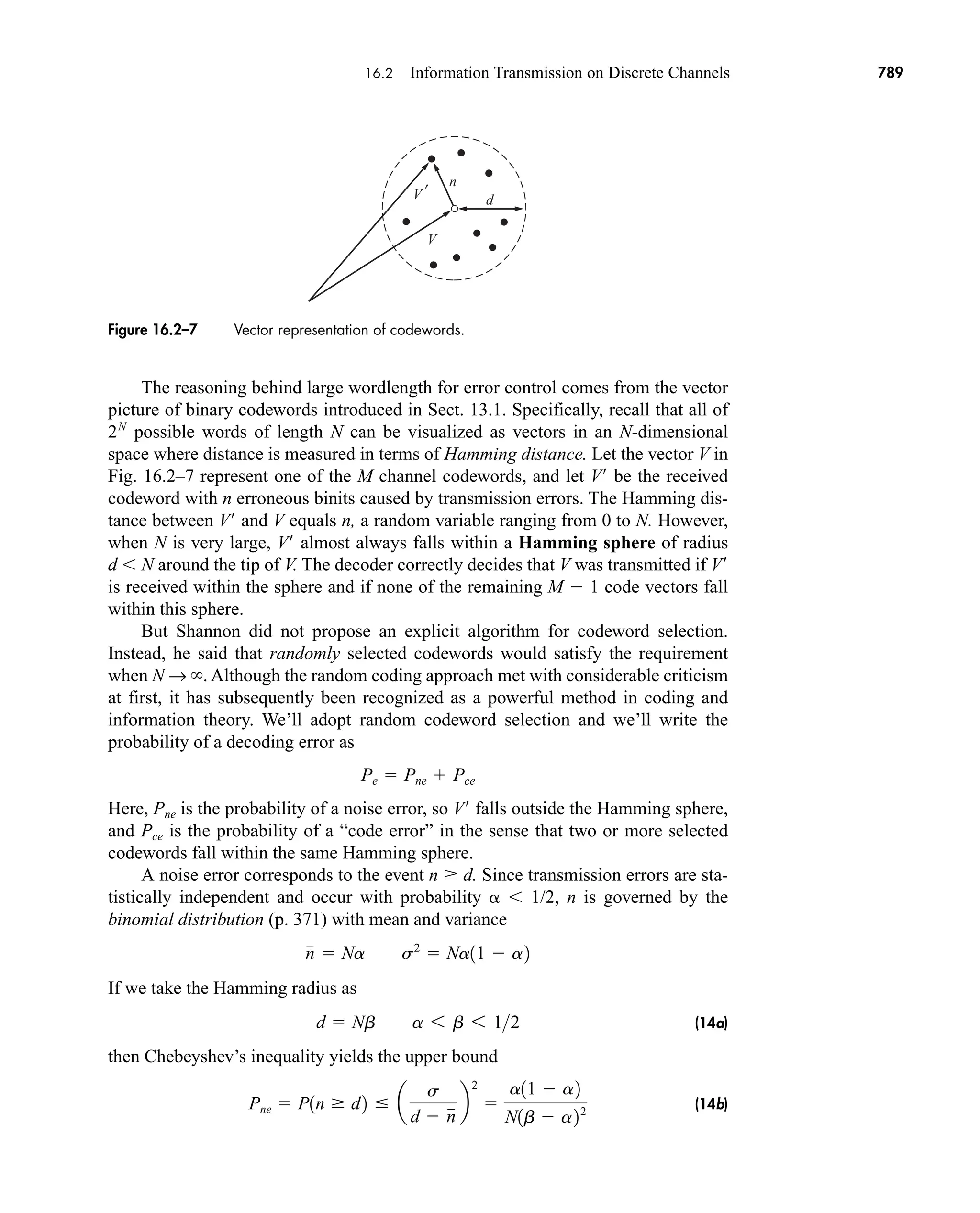

(6b)

where we have drawn upon the commutativity of convolution.

Either form of Eq. (6) is called the superposition integral. It expresses the

forced response as a convolution of the input x(t) with the impulse response h(t).

System analysis in the time domain therefore requires knowledge of the impulse

response along with the ability to carry out the convolution.

Various techniques exist for determining h(t) from a differential equation or some other

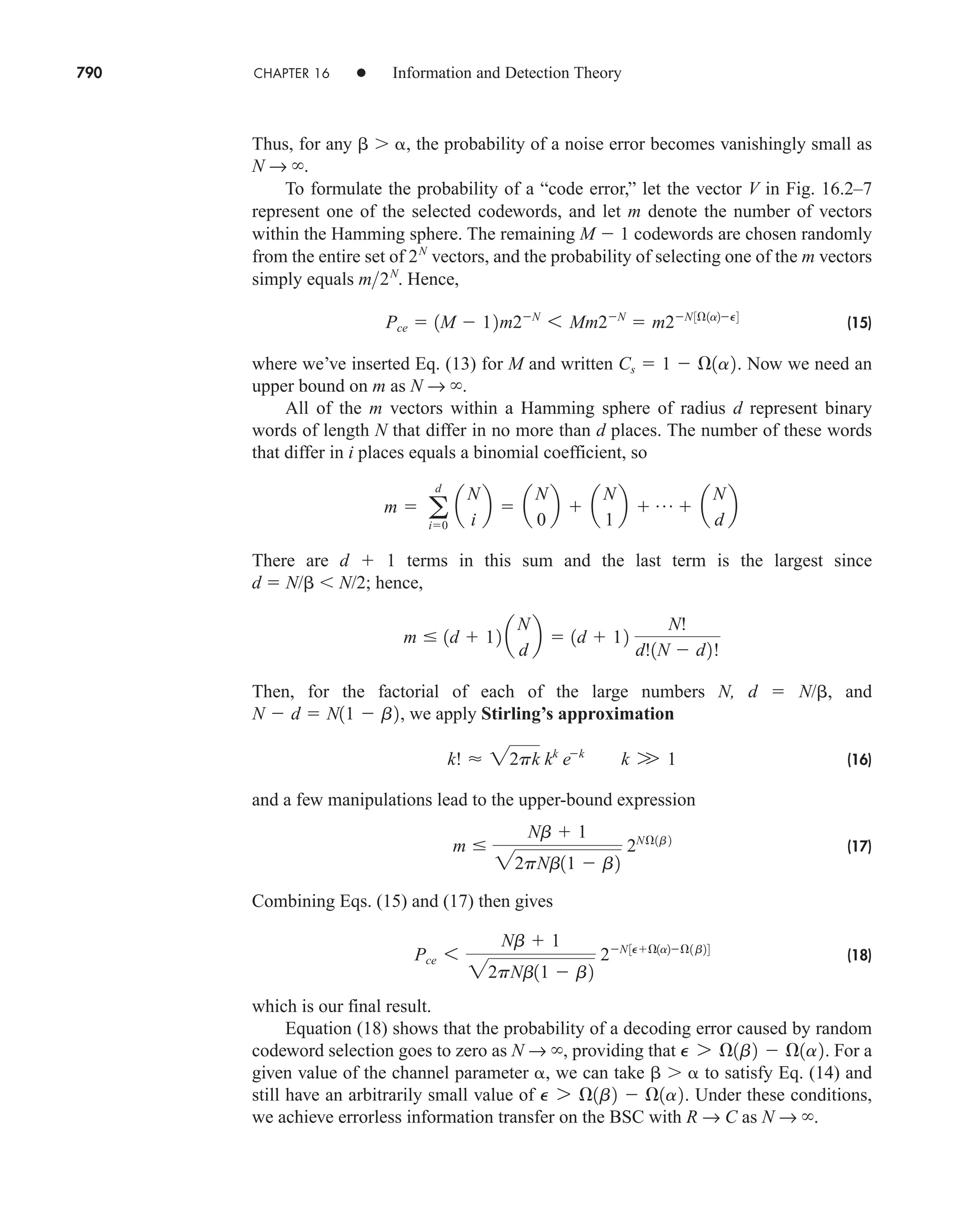

system model. However, you may be more comfortable taking and calculating

the system’s step response

(7a)

from which

(7b)

This derivative relation between the impulse and step response follows from the gen-

eral convolution property

Thus, since g(t) h(t) * u(t) by definition, dg(t)/dt h(t) * [du(t)/dt] h(t) * d (t) h(t).

d

dt

3v1t2 * w1t2 4 v1t2 * c

dw1t2

dt

d

h1t2

dg1t2

dt

g1t2

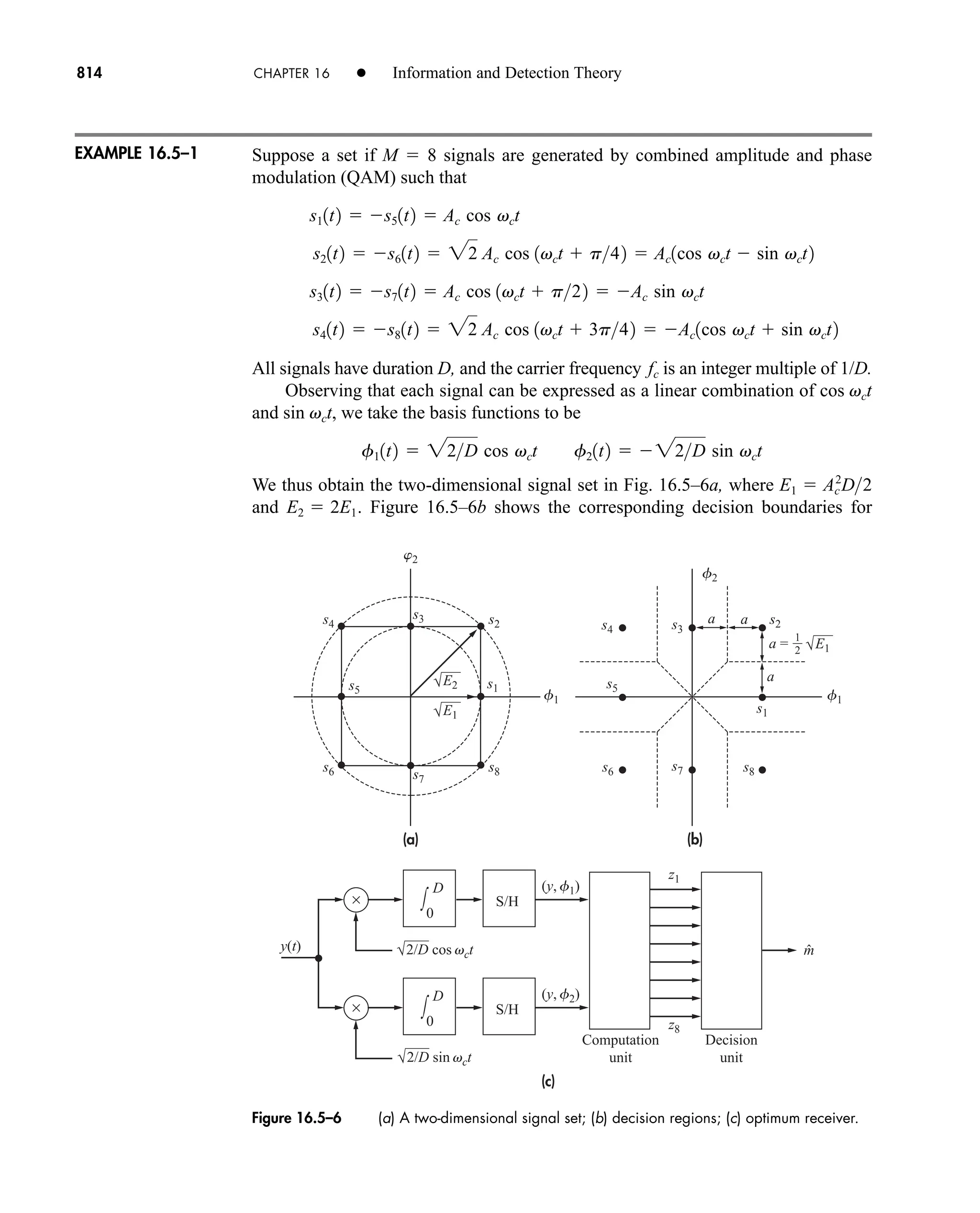

^

F3u1t2 4

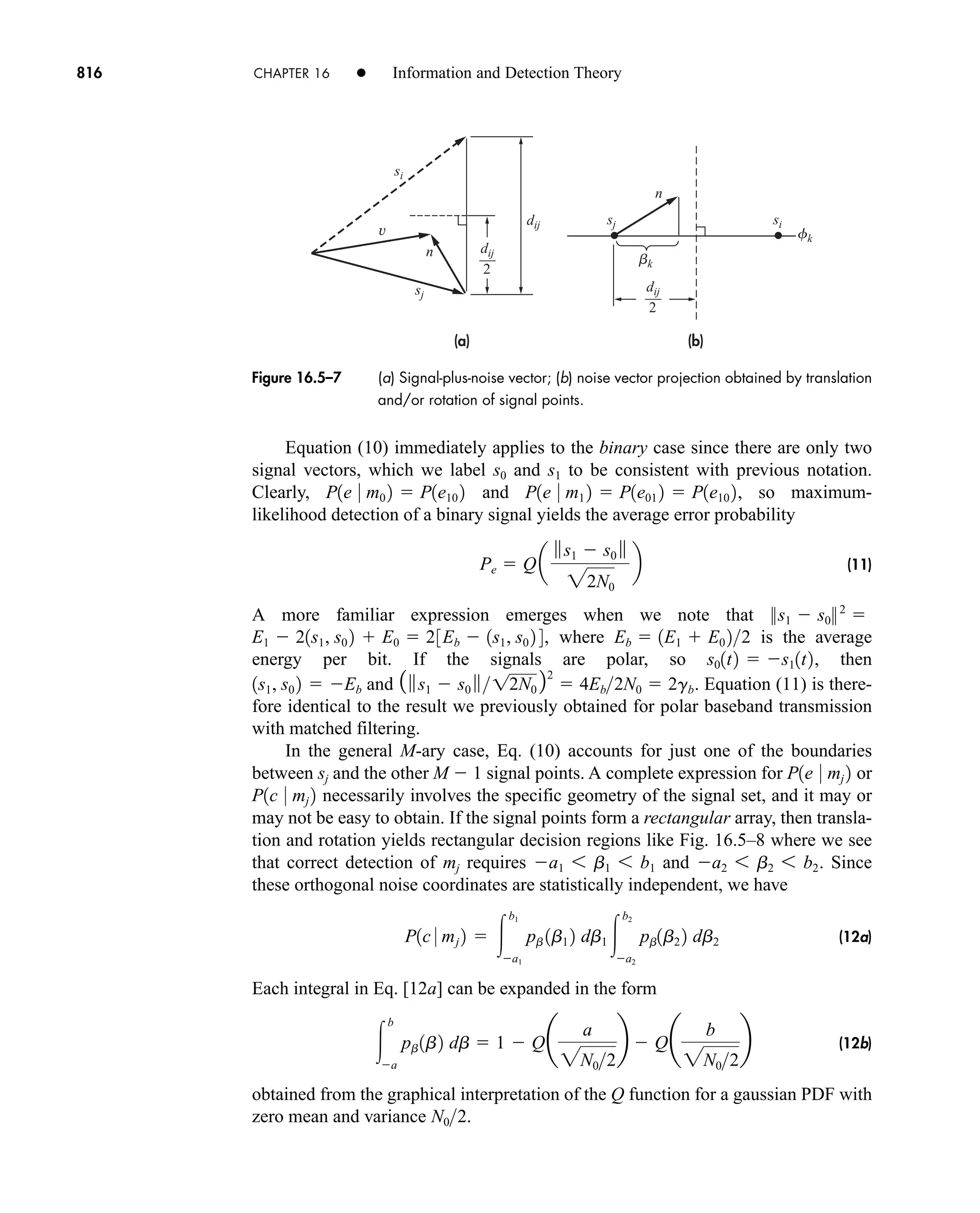

x1t2 u1t2

q

q

h1l2x1t l2 dl

y1t2

q

q

x1l2h1t l2 dl

F3d1t l2 4 h1t l2

q

q

x1l2F3d1t l2 4 dl

y1t2 F c

q

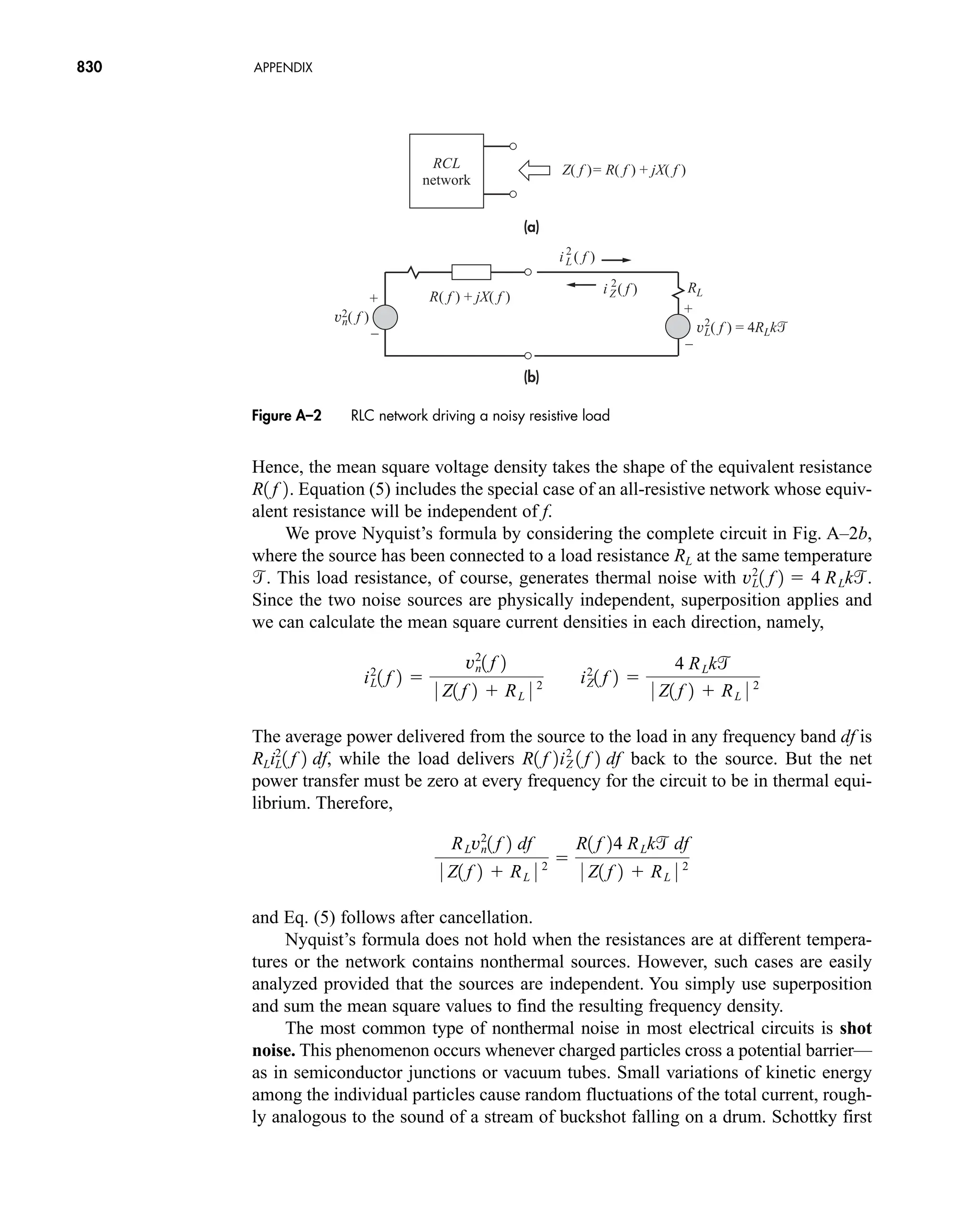

q

x1l2d1t l2 dld

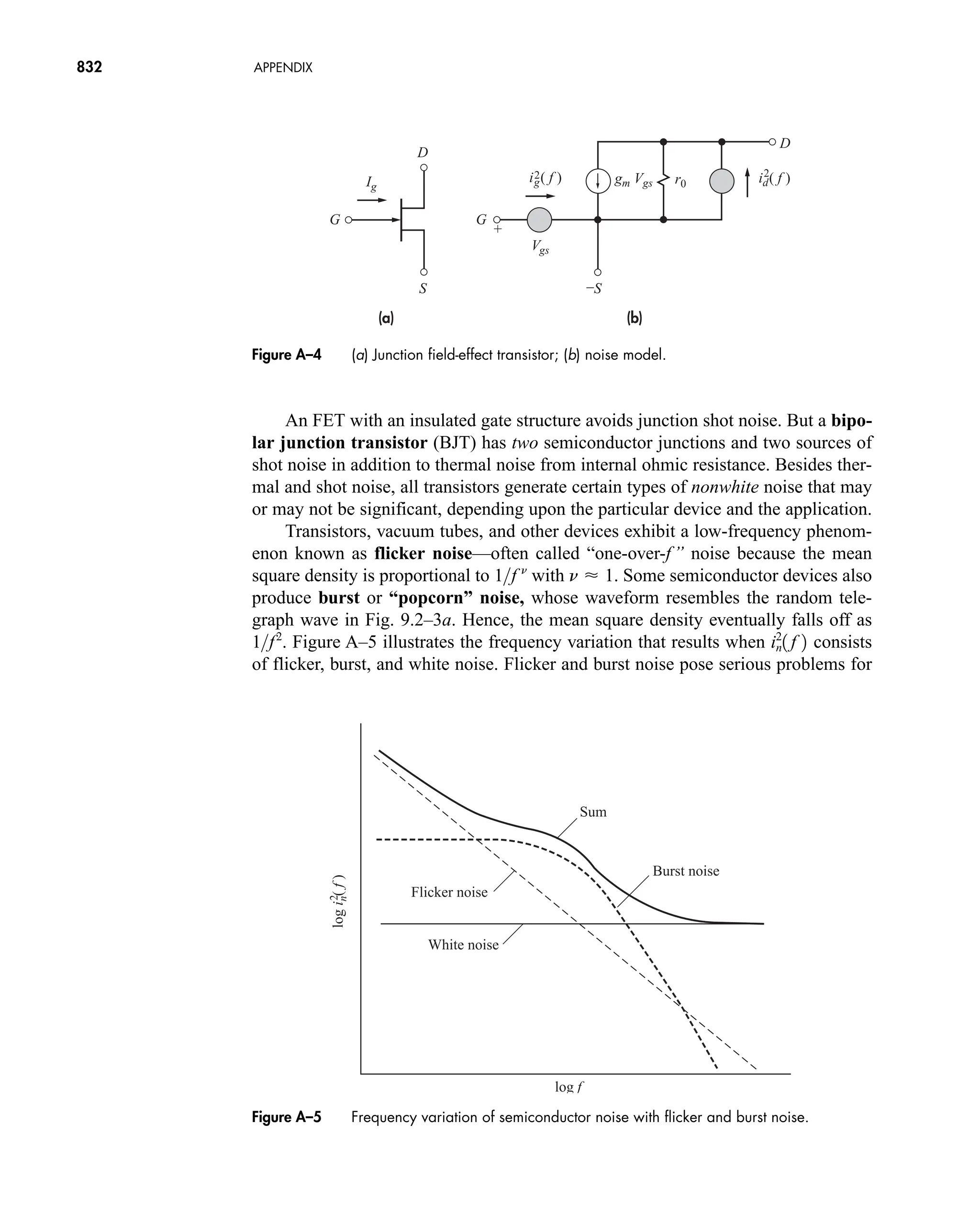

x1t2 x1t2 * d1t2

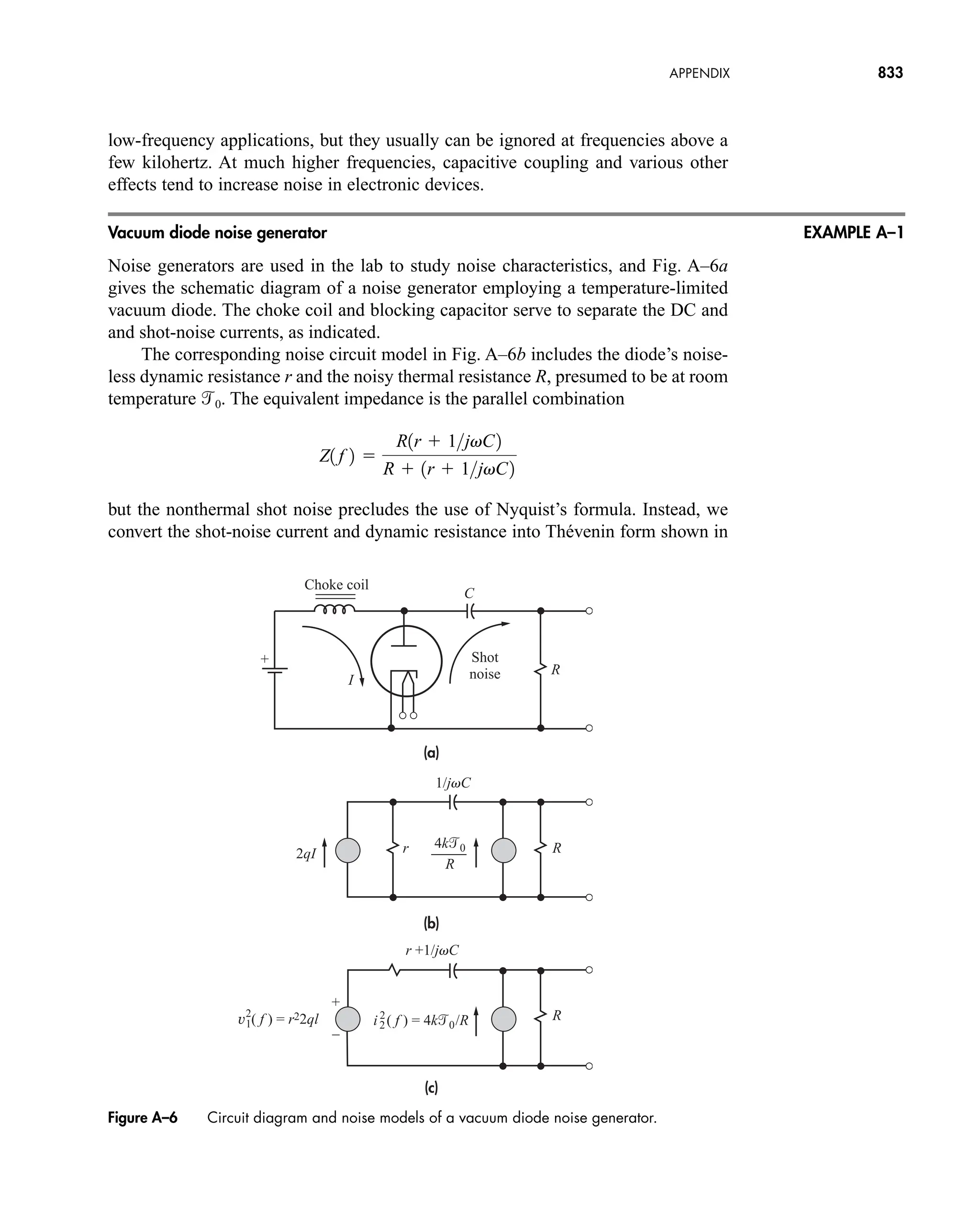

x1t2 d1t2

h1t2

^

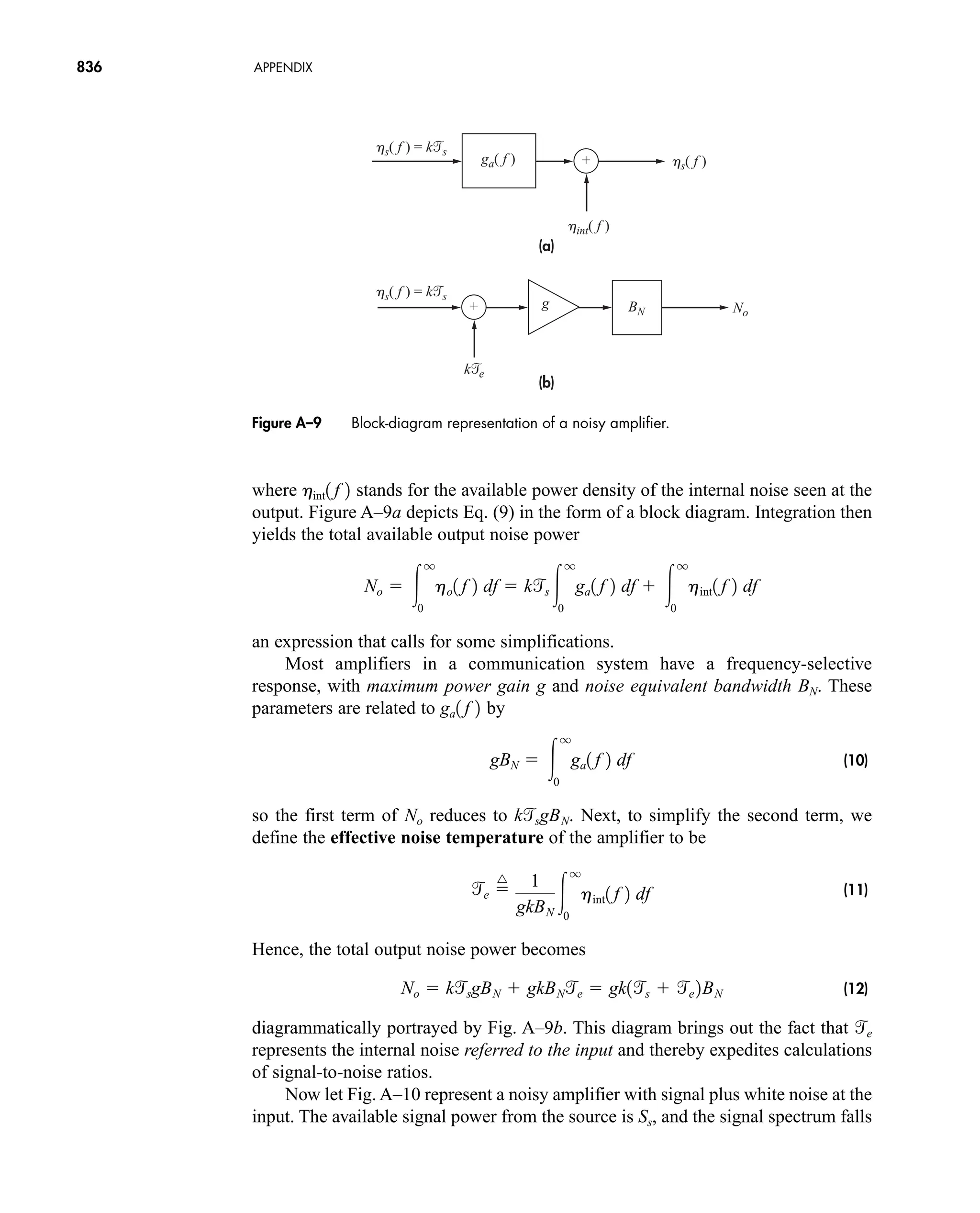

F3d1t2 4

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-116-2048.jpg)

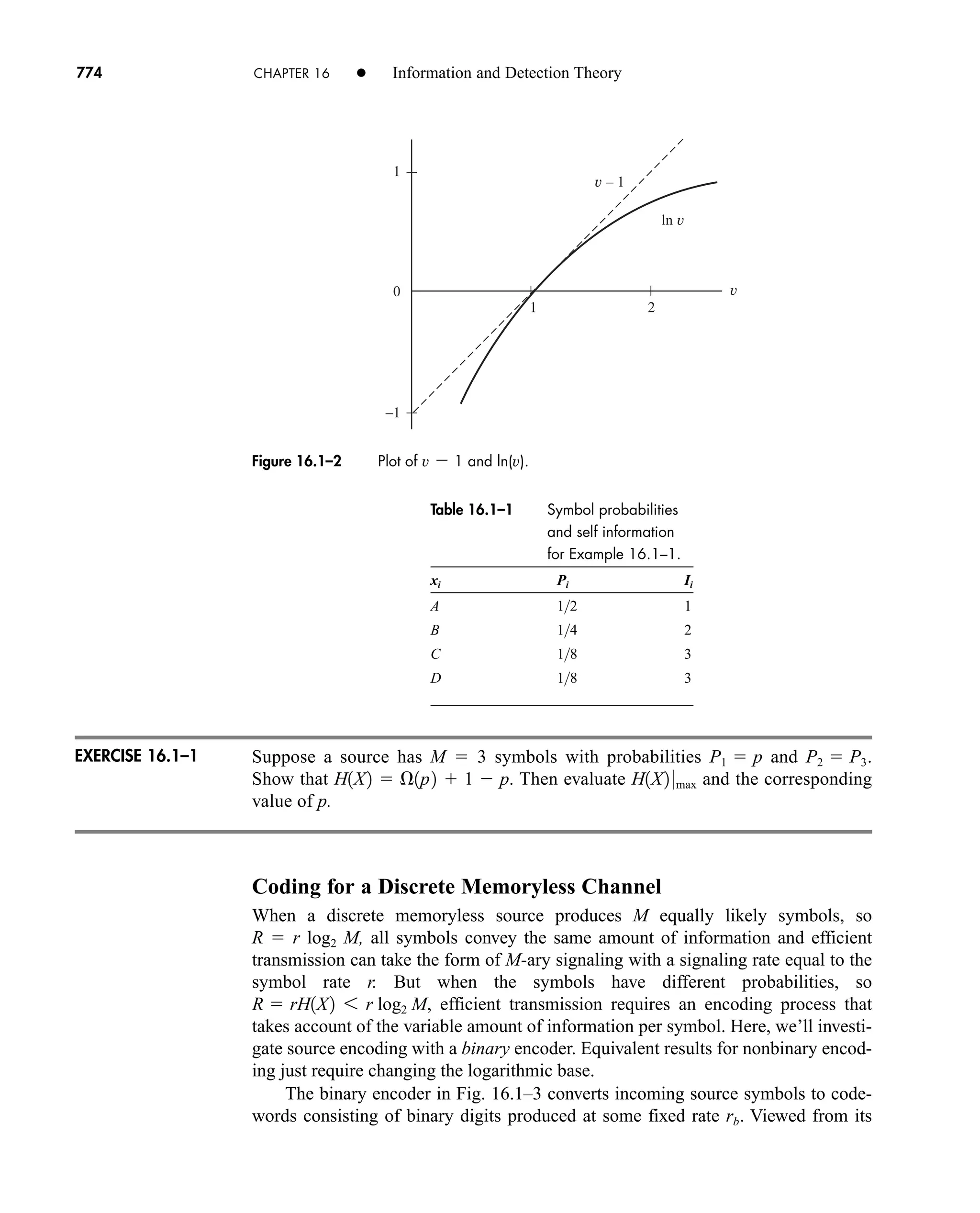

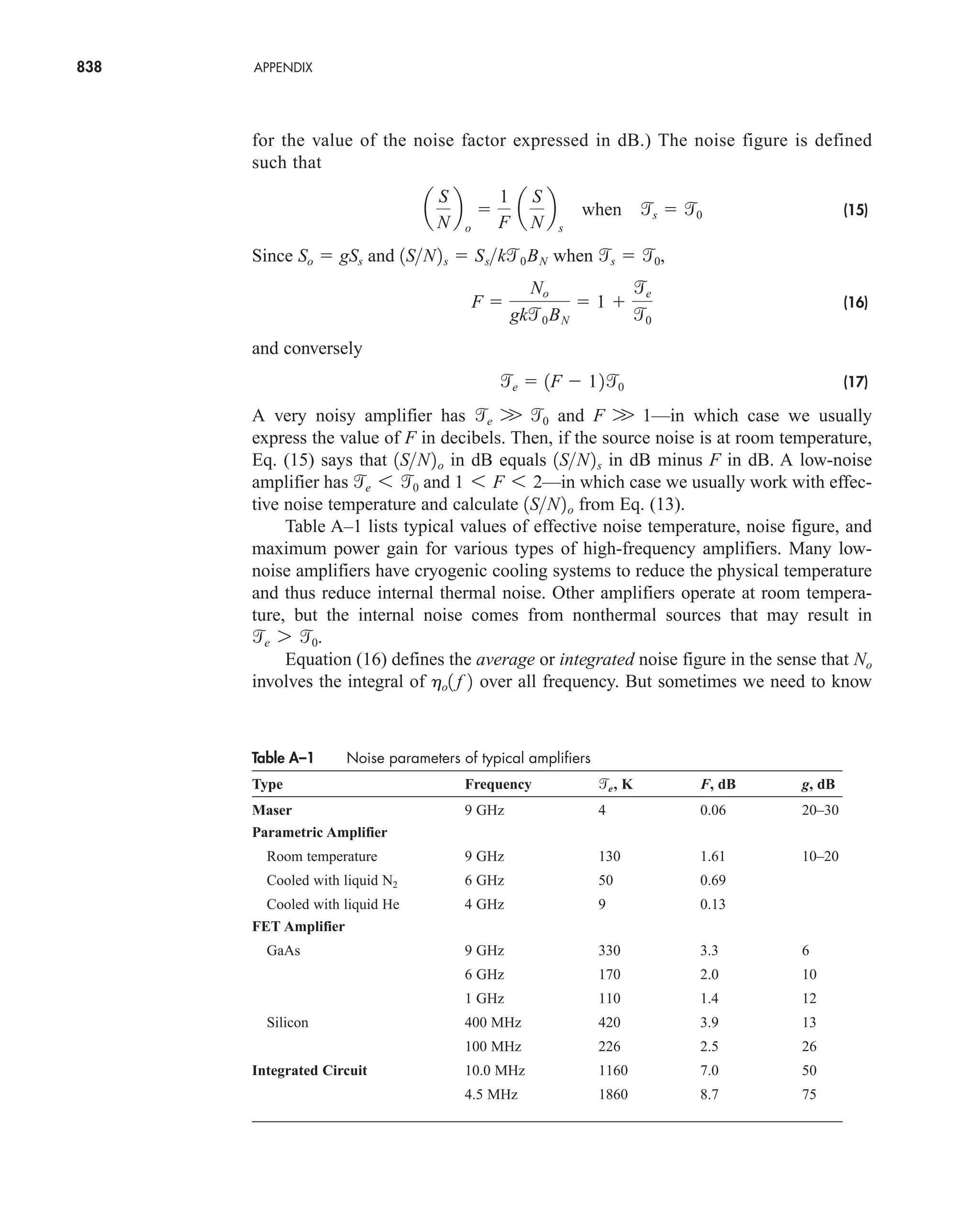

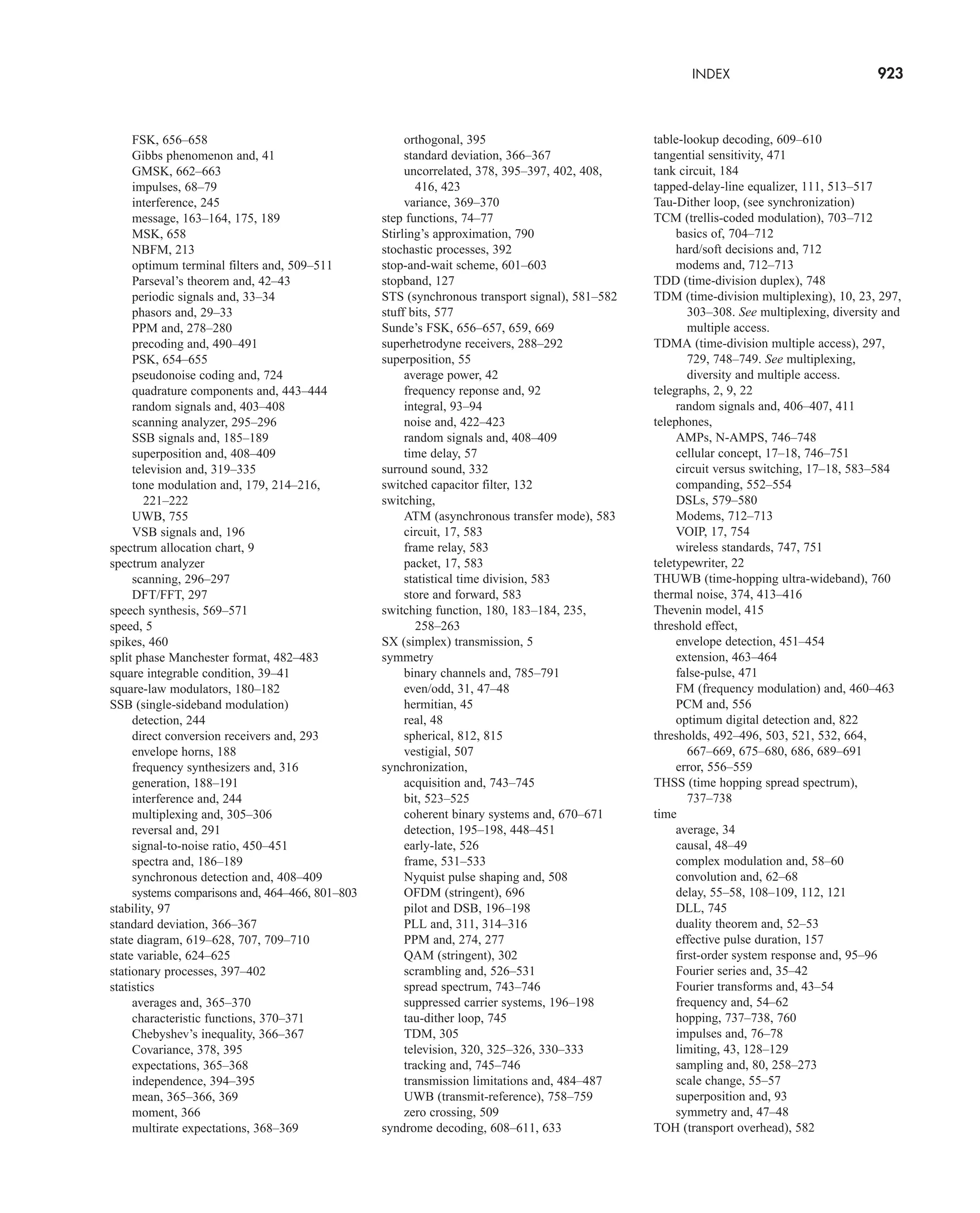

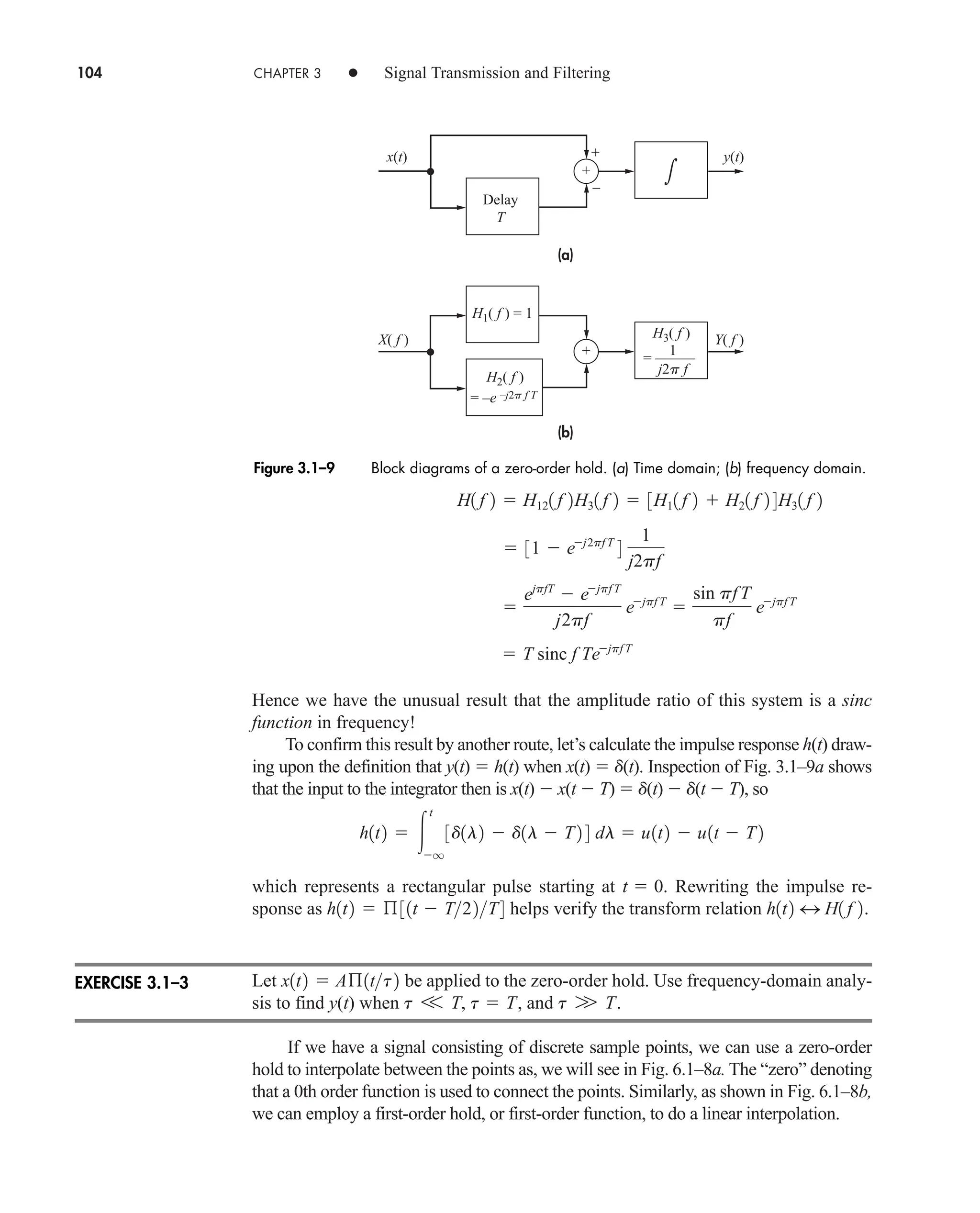

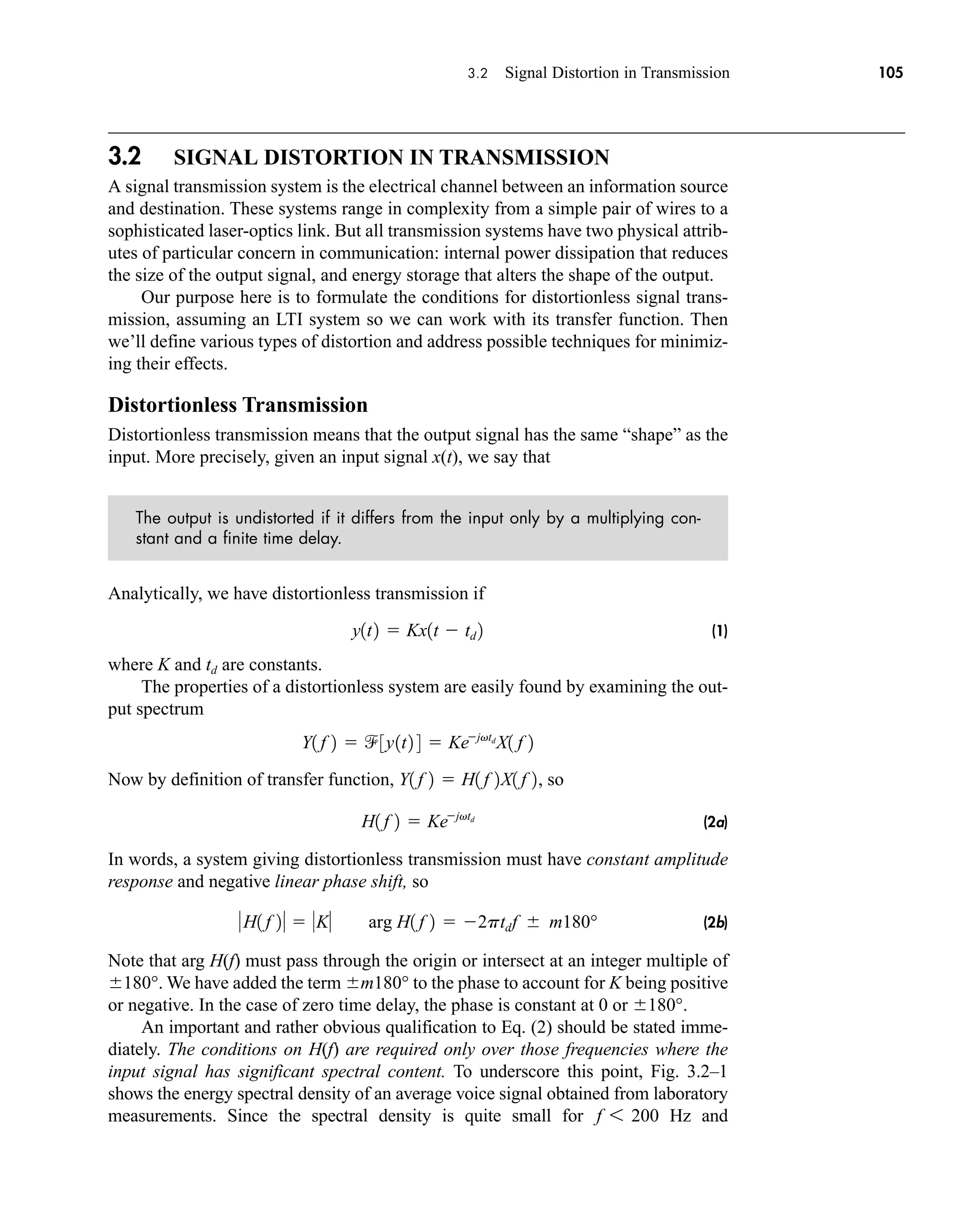

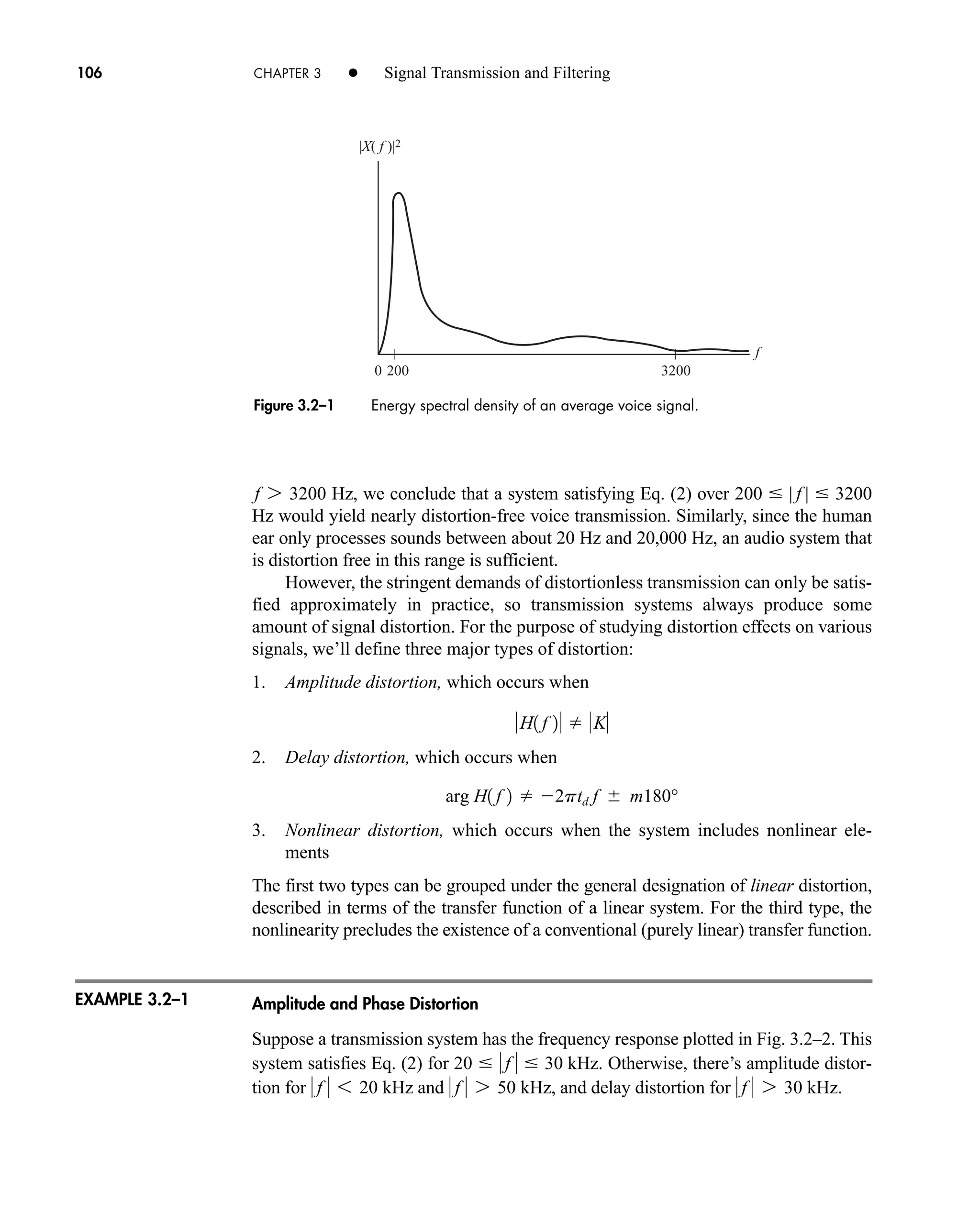

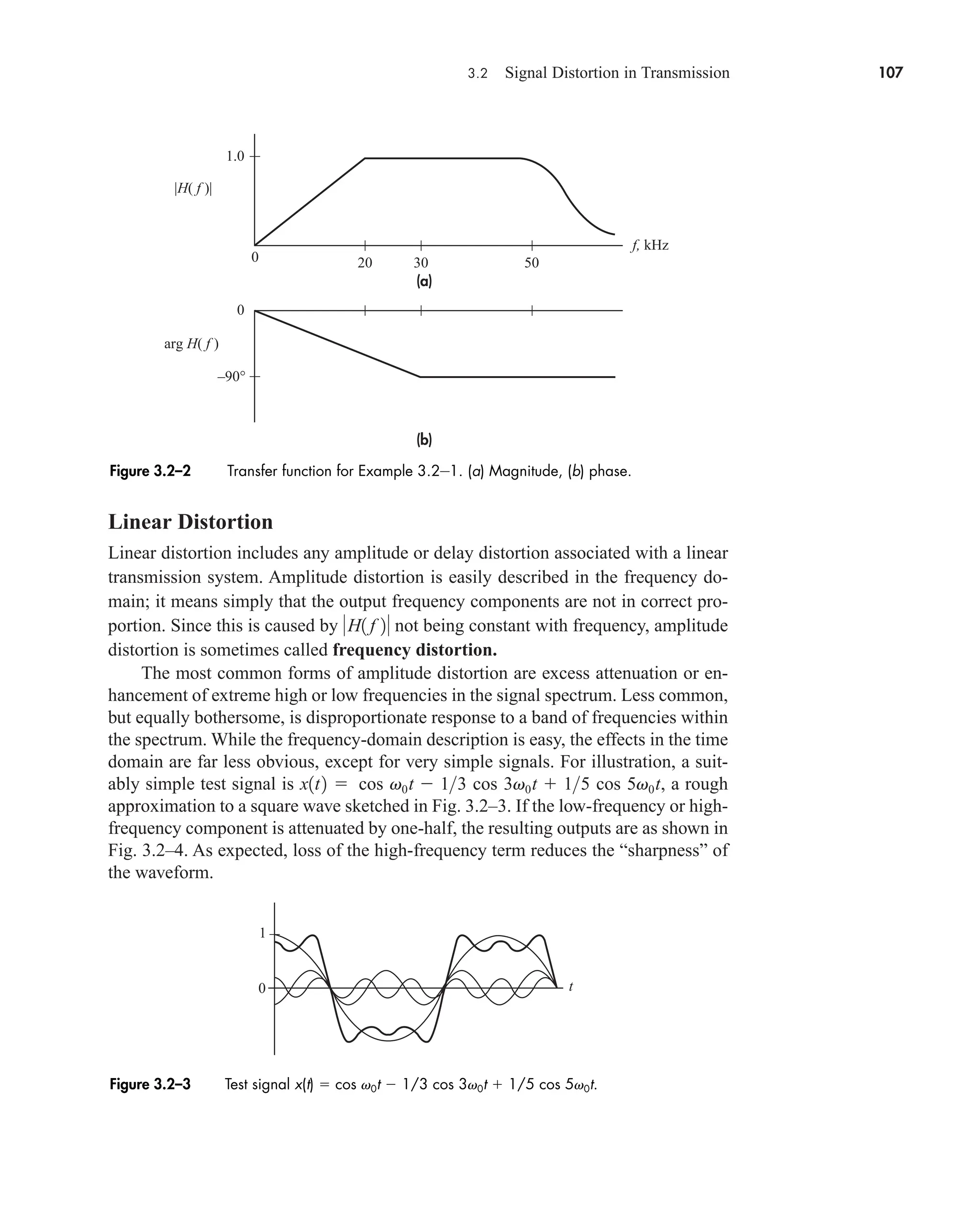

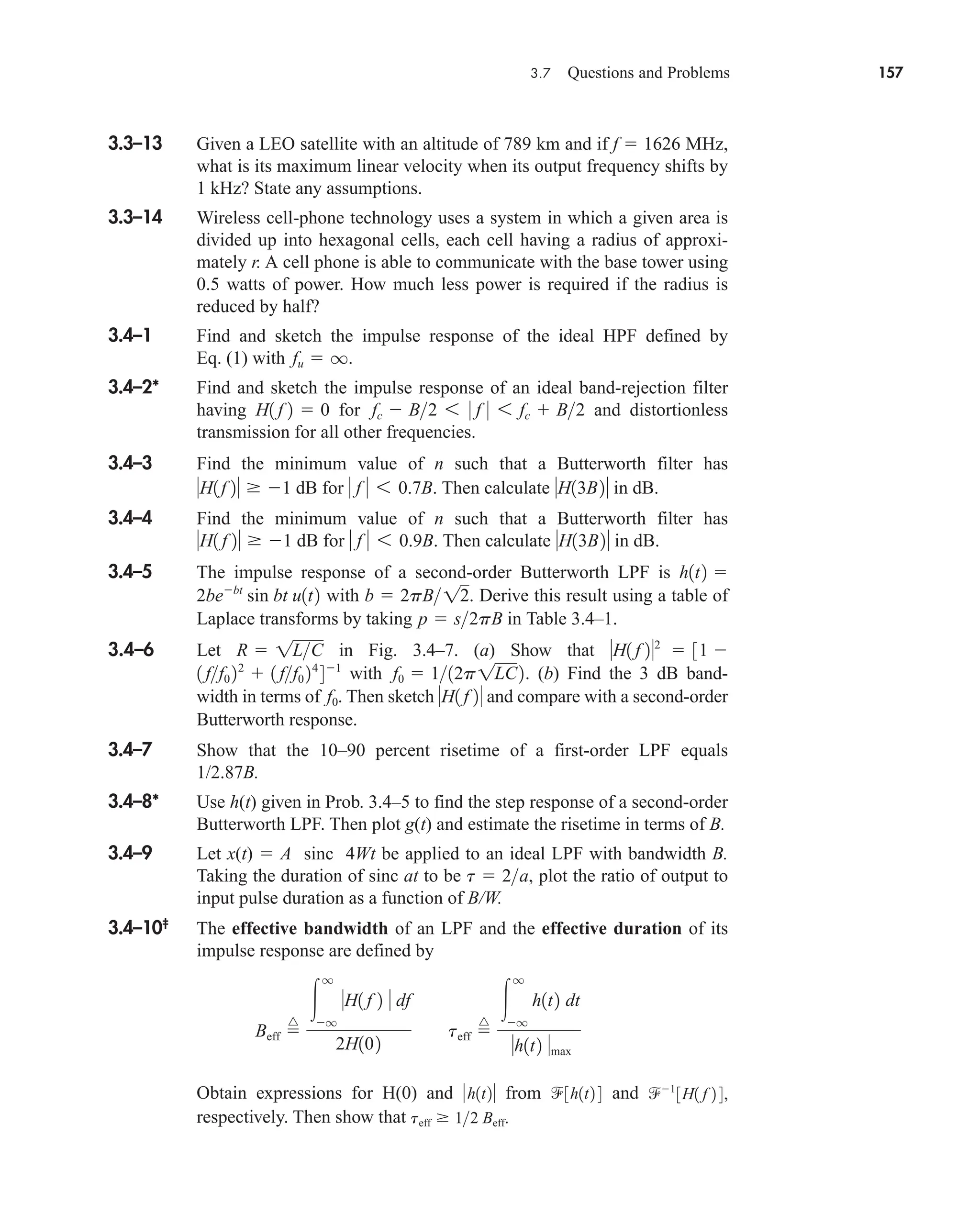

![3.1 Response of LTI Systems 103

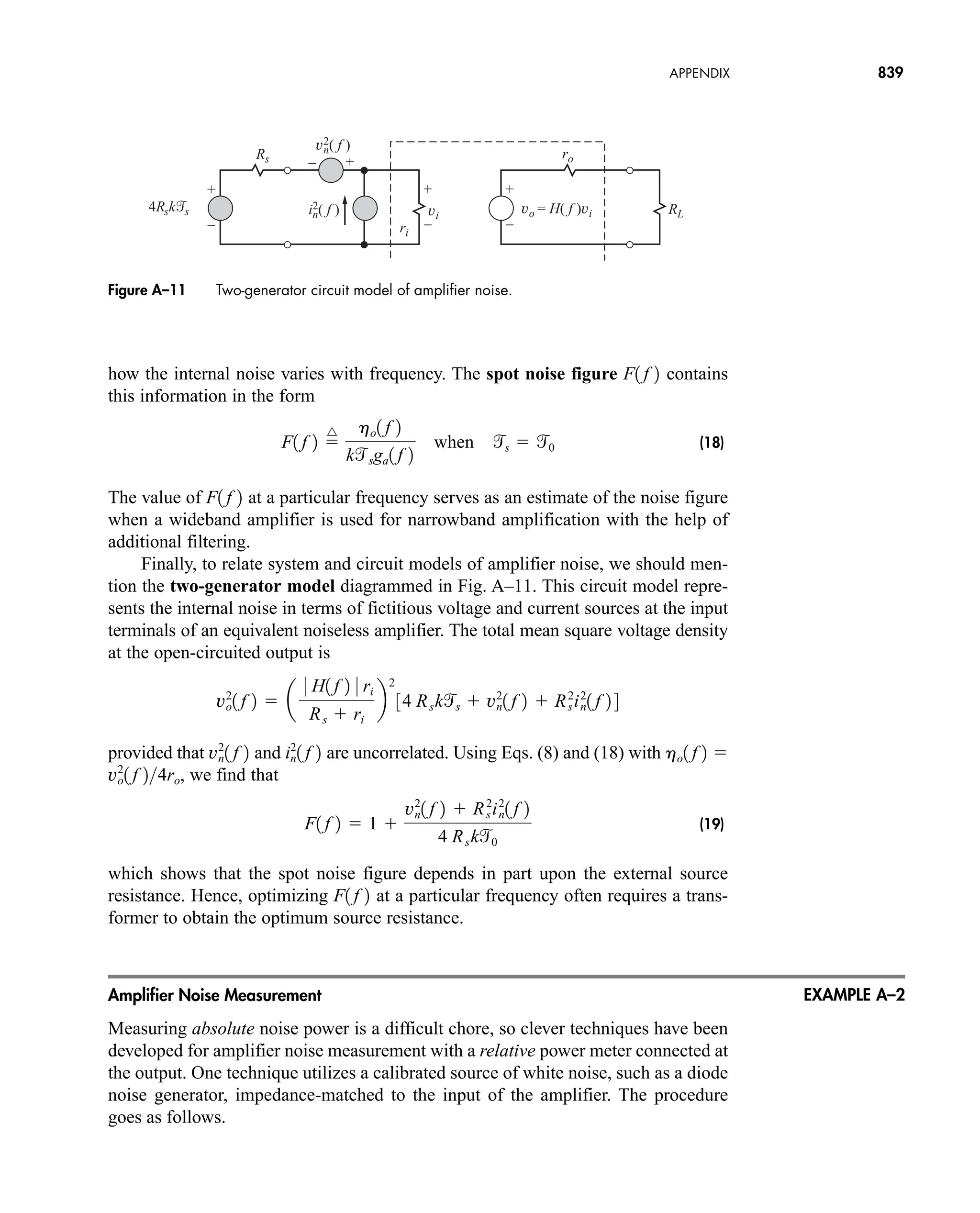

Figure 3.1–8 (a) Parallel connection; (b) cascade connection; (c) feedback connection.

(19c)

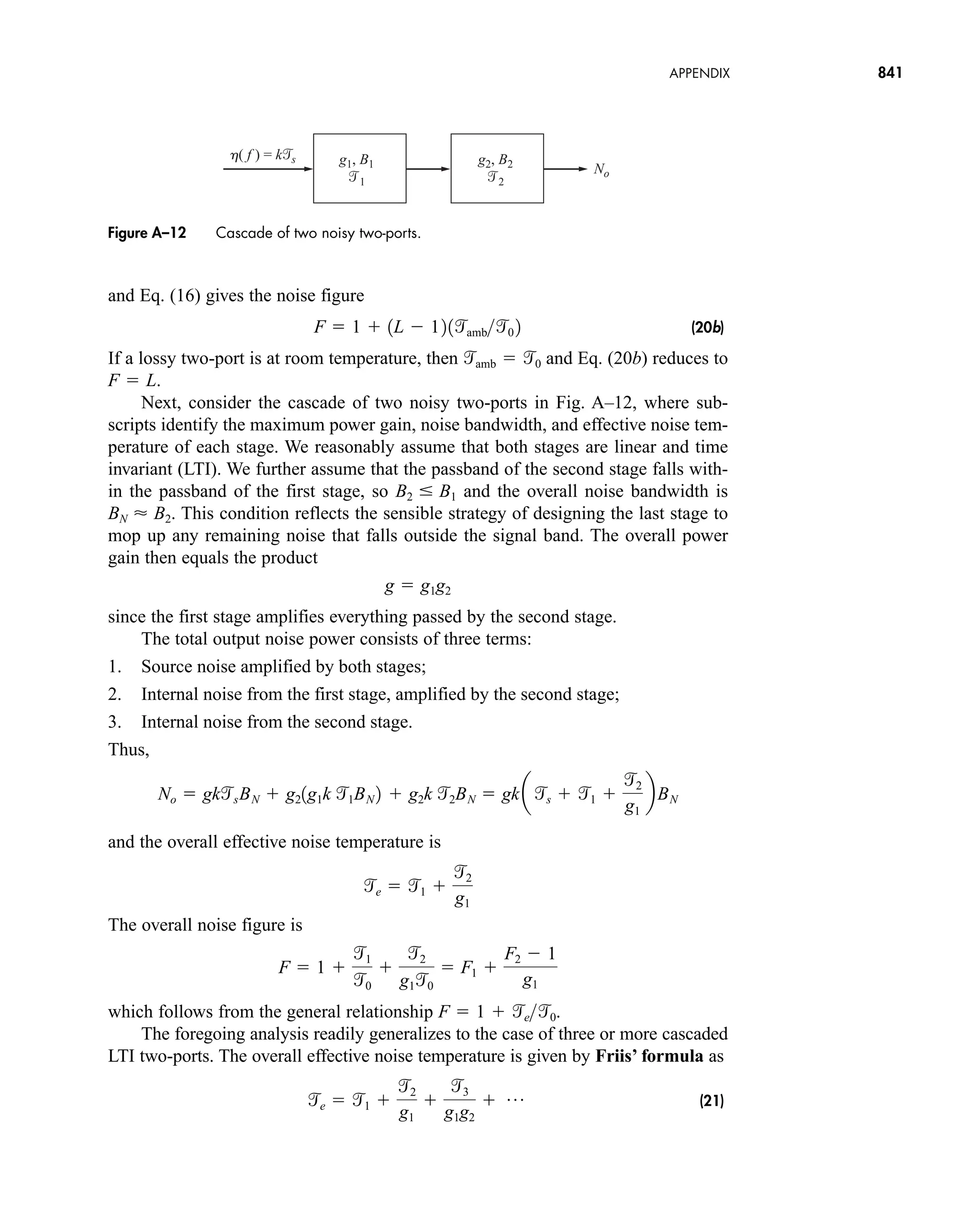

This case is more properly termed the negative feedback connection as distinguished

from positive feedback, where the returned signal is added to the input instead of

subtracted.

Zero-Order Hold

The zero-order hold system in Fig. 3.1–9a has several applications in electrical com-

munication. Here we take it as an instructive exercise of the parallel and cascade re-

lations. But first we need the individual transfer functions, determined as follows:

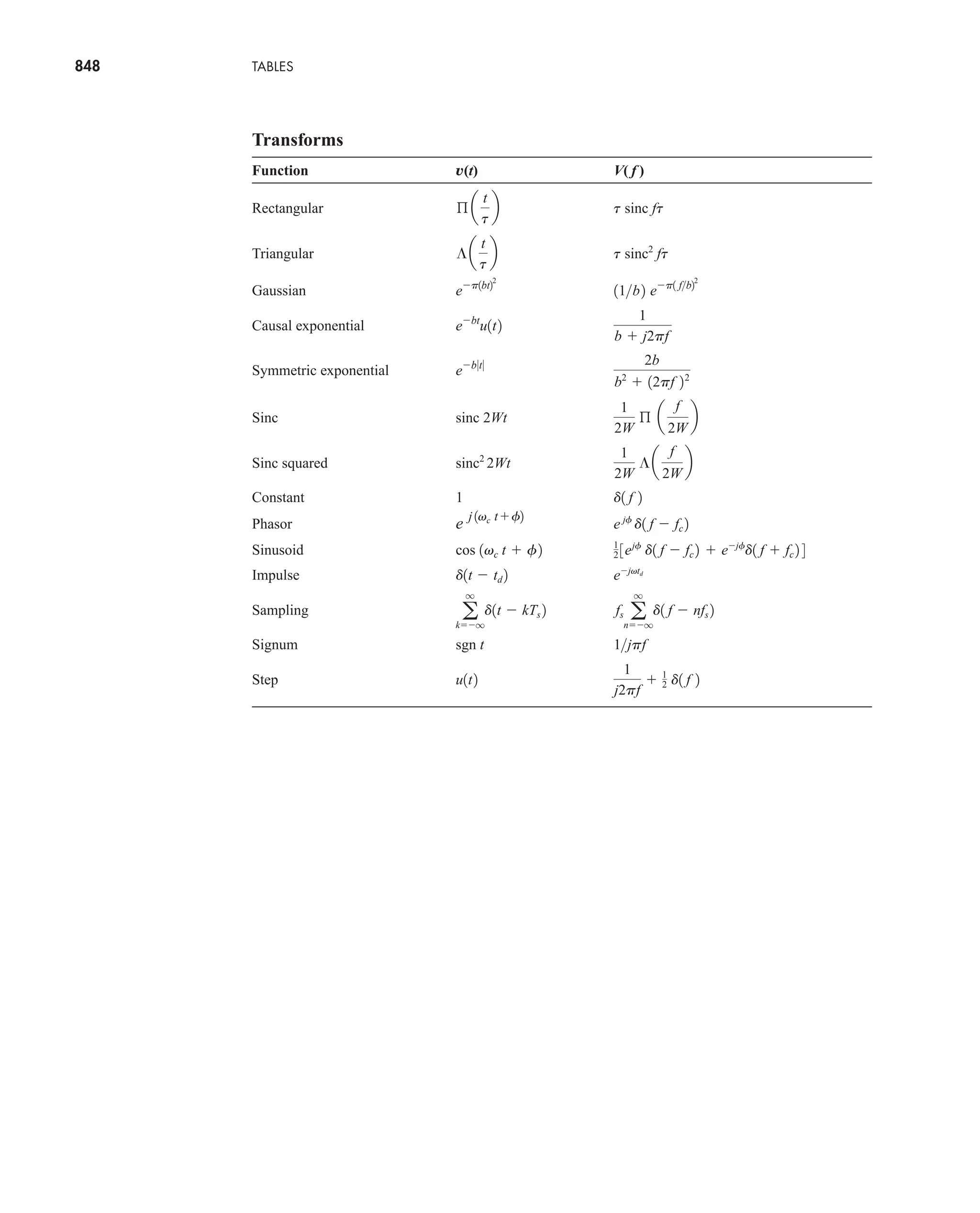

the upper branch of the parallel section is a straight-through path so, trivially,

; the lower branch produces pure time delay of T seconds followed by

sign inversion, and lumping them together gives ; the integrator in

the final block has . Figure 3.1–9b is the equivalent block diagram

in terms of these transfer functions.

Having gotten this far, the rest of the work is easy. We combine the parallel

branches in and use the cascade rule to obtain

H121 f 2 H11 f 2 H21 f 2

H31 f 2 1j2pf

H21 f 2 ej2pfT

H11 f 2 1

H1f2

H11f2

1 H11f2H21f2

Feedback connection

+

–

(a)

(b)

(c)

+

+

H1( f )

H1( f ) X( f )

H2( f ) X( f )

H1( f ) X( f )

H2( f ) Y( f )

H1( f )

Y( f ) = [H1( f ) + H2( f )] X( f )

1 + H1( f )H2( f )

Y( f ) = ––––––––––––––––– X( f )

Y( f ) = H1( f )H2( f ) X( f )

X( f )

X( f )

X( f )

H1( f ) H2( f )

H2( f )

H1( f )

H2( f )

EXAMPLE 3.1–3

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 103](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-125-2048.jpg)

![114 CHAPTER 3 • Signal Transmission and Filtering

We’ll consider only memoryless devices, for which the transfer characteristic is a

complete description. It should be noted that the transfer function is a purely linear

concept and is only relevant in linear or linearized systems.

Under small-signal input conditions, it may be possible to linearize the transfer

characteristic in a piecewise fashion, as shown by the thin lines in the figure. The

more general approach is a polynomial approximation to the curve, of the form

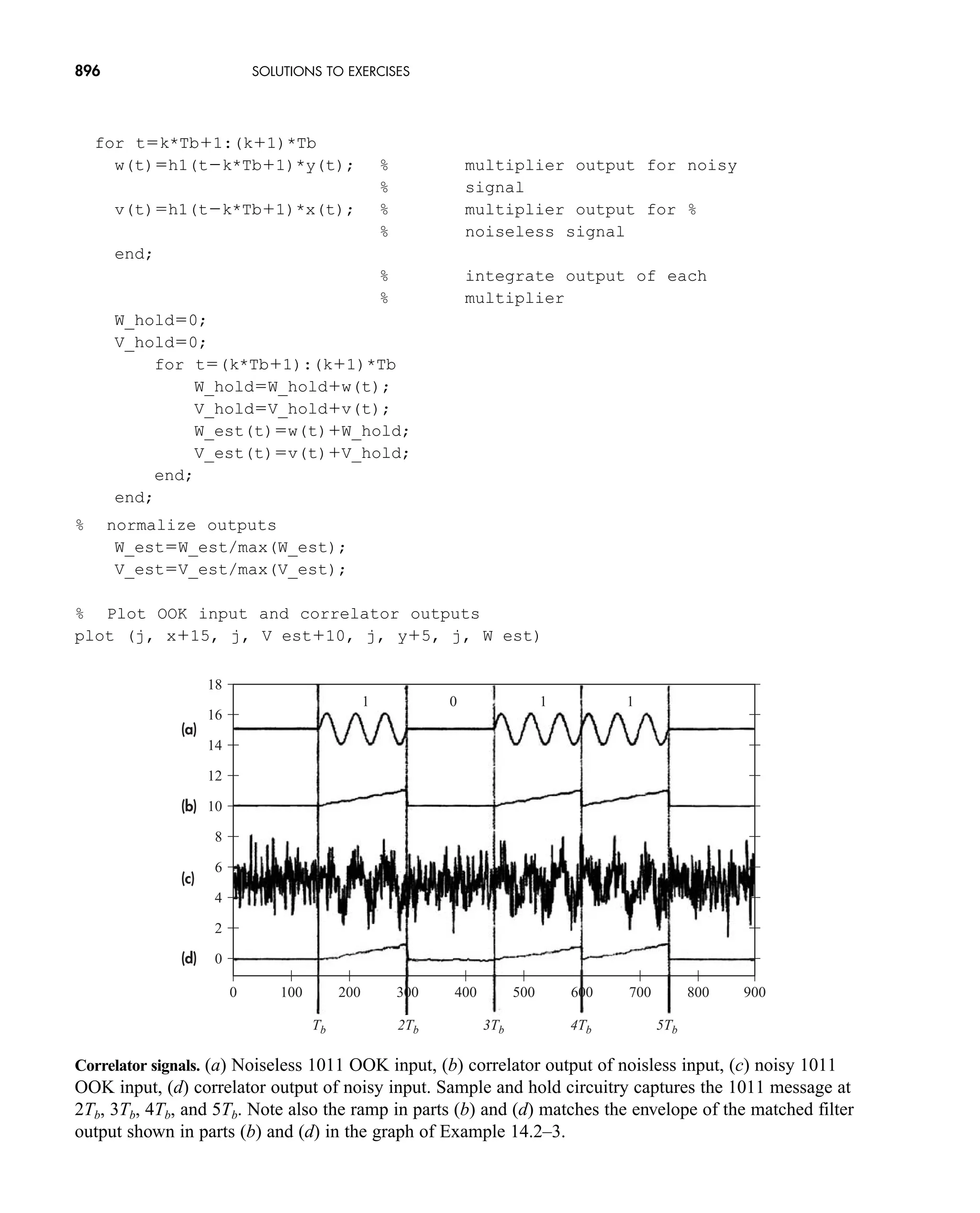

(12a)

and the higher powers of x(t) in this equation give rise to the nonlinear distortion.

Even though we have no transfer function, the output spectrum can be found, at least

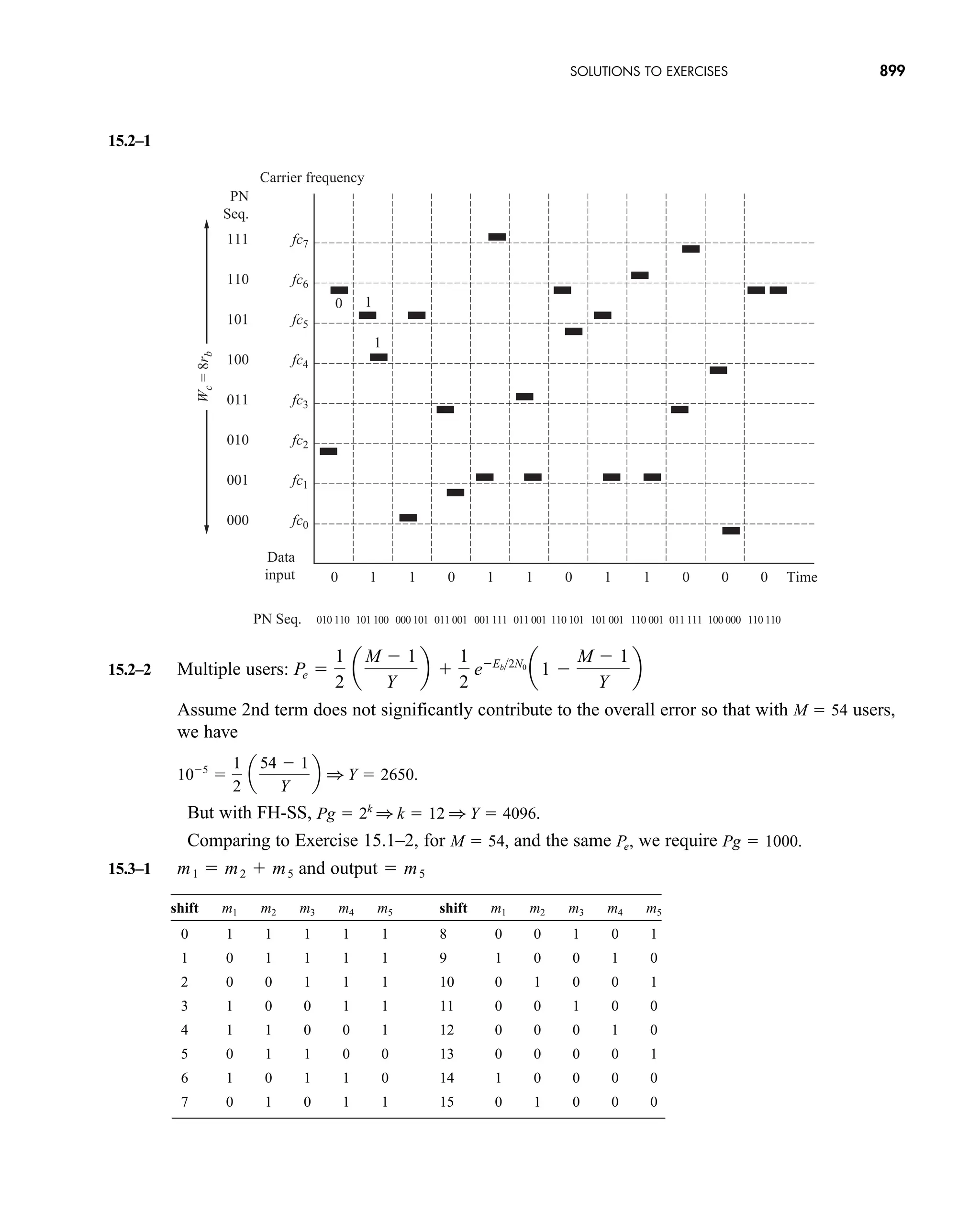

in a formal way, by transforming Eq. (12a). Specifically, invoking the convolution theorem,

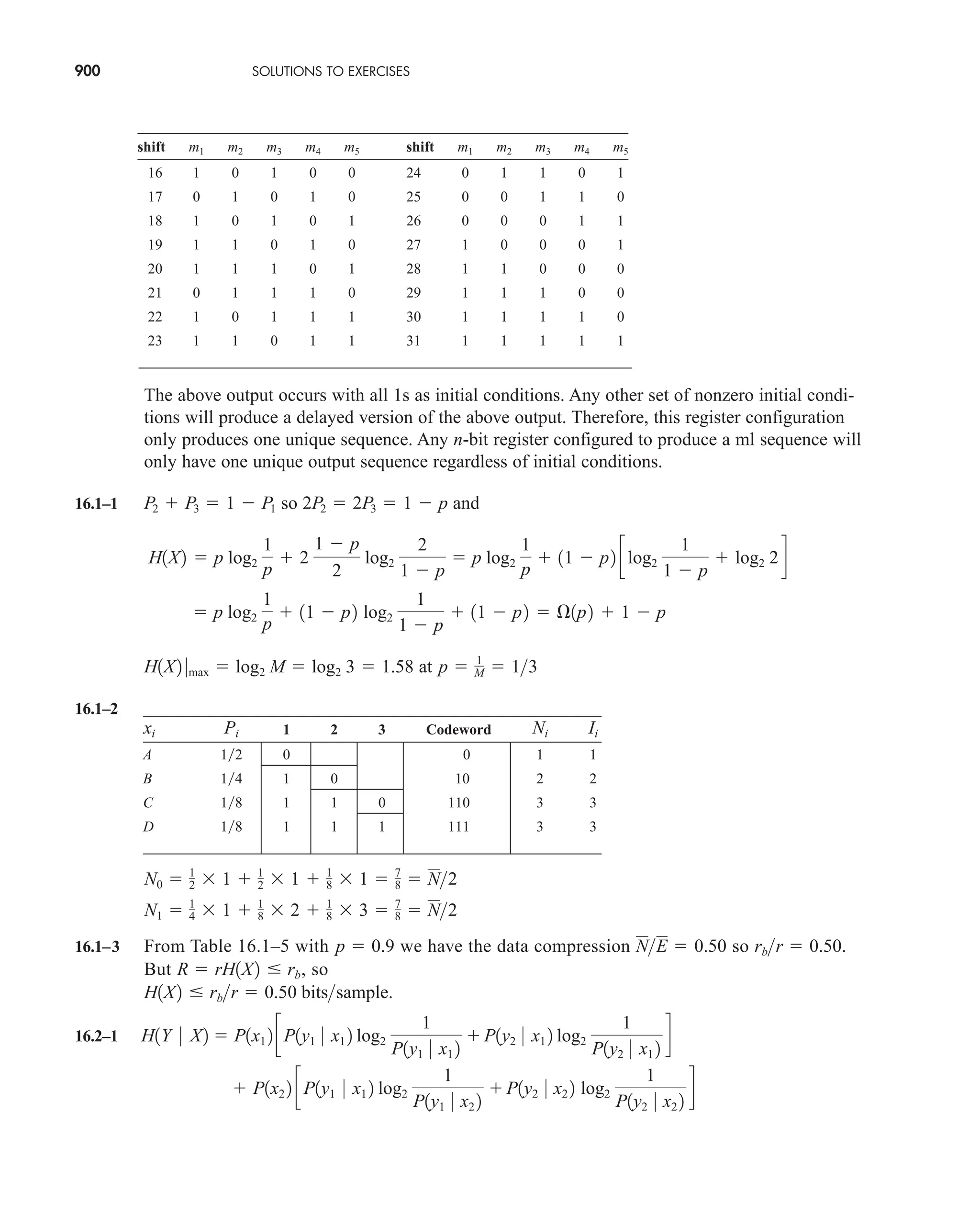

(12b)

Now if x(t) is bandlimited in W, the output of a linear network will contain no fre-

quencies beyond But in the nonlinear case, we see that the output includes

, which is bandlimited in , which is bandlimited in ,

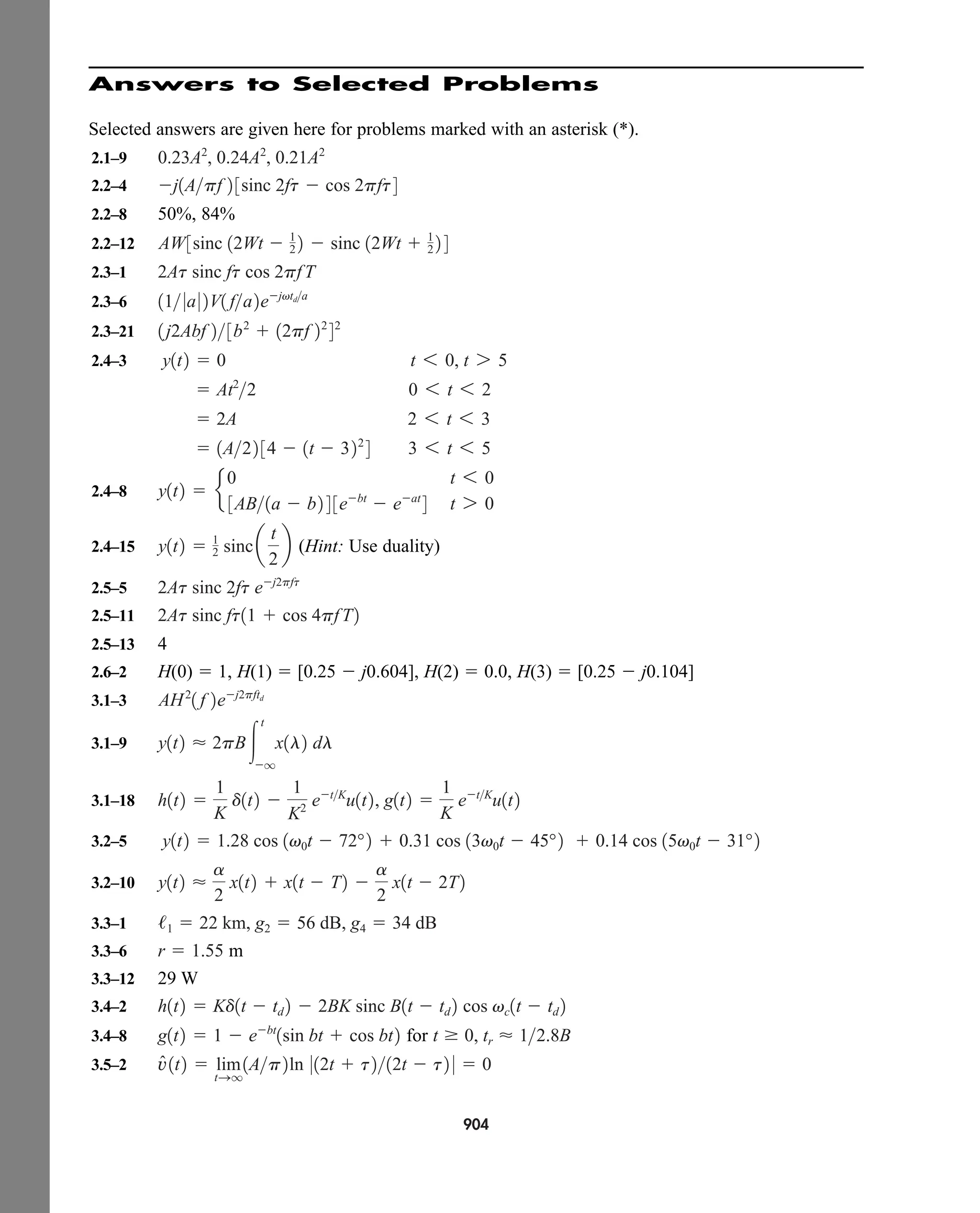

and so on. The nonlinearities have therefore created output frequency components

that were not present in the input. Furthermore, since may contain compo-

nents for this portion of the spectrum overlaps that of . Using filtering

techniques, the added components at can be removed, but there is no con-

venient way to get rid of the added components at These, in fact, constitute

the nonlinear distortion.

A quantitative measure of nonlinear distortion is provided by taking a simple co-

sine wave, , as the input. Inserting in Eq. (12a) and expanding yields

a

a2

2

a4

4

pb cos 2v0t p

y1t2 a

a2

2

3a4

8

pb aa1

3a3

4

pb cos v0t

x1t2 cos v0t

f 6 W.

f 7 W

X1 f 2

f 6 W,

X * X1 f 2

3W

2W, X * X * X1 f 2

X * X1 f 2

f 6 W.

Y1 f 2 a1 X1 f 2 a2 X * X1 f 2 a3 X * X * X1 f 2 p

y1t2 a1 x1t2 a2 x2

1t2 a3 x3

1t2 p

x

y = T[x]

Figure 3.2–10 Transfer characteristic of a nonlinear device.

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 114](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-136-2048.jpg)

![3.2 Signal Distortion in Transmission 115

Therefore, the nonlinear distortion appears as harmonics of the input wave. The

amount of second-harmonic distortion is the ratio of the amplitude of this term to

that of the fundamental, or in percent:

Higher-order harmonics are treated similarly. However, their effect is usually much

less, and many can be removed entirely by filtering.

If the input is a sum of two cosine waves, say cos , the output will

include all the harmonics of f1 and f2, plus crossproduct terms which yield

f2 f1, f2 f1, f2 2f1, etc. These sum and difference frequencies are designated as

intermodulation distortion. Generalizing the intermodulation effect, if x(t) x1(t) x2(t),

then y(t) contains the cross-product x1(t)x2(t) (and higher-order products, which we ignore

here). In the frequency domain x1(t)x2(t) becomes X1 * X2(f); and even though X1(f)

and X2(f) may be separated in frequency, X1 * X2(f) can overlap both of them, pro-

ducing one form of crosstalk. Note that nonlinearity is not required for other forms

of crosstalk (e.g., signals traveling over adjacent cables can have crosstalk). This as-

pect of nonlinear distortion is of particular concern in telephone transmission sys-

tems. On the other hand the cross-product term is the desired result when nonlinear

devices are used for modulation purposes.

It is important to note the difference between crosstalk and other types of inter-

ference. Crosstalk occurs when one signal crosses over to the frequency band of an-

other signal due to nonlinear distortion in the channel. Picking up a conversation on

a cordless phone or baby monitor occurs because the frequency spectrum allocated

to such devices is too crowded to accommodate all of the users on separate frequen-

cy carriers. Therefore some “sharing” may occur from time to time. While crosstalk

resulting from nonlinear distortion is now rare in telephone transmission due to ad-

vances in technology, it was a major problem at one time.

The cross-product term is the desired result when nonlinear devices are used for

modulation purposes. In Sect. 4.3 we will examine how nonlinear devices can be

used to achieve amplitude modulation. In Chap. 5, carefully controlled nonlinear dis-

tortion again appears in both modulation and detection of FM signals.

Although nonlinear distortion has no perfect cure, it can be minimized by care-

ful design. The basic idea is to make sure that the signal does not exceed the linear

operating range of the channel’s transfer characteristic. Ironically, one strategy along

this line utilizes two nonlinear signal processors, a compressor at the input and an

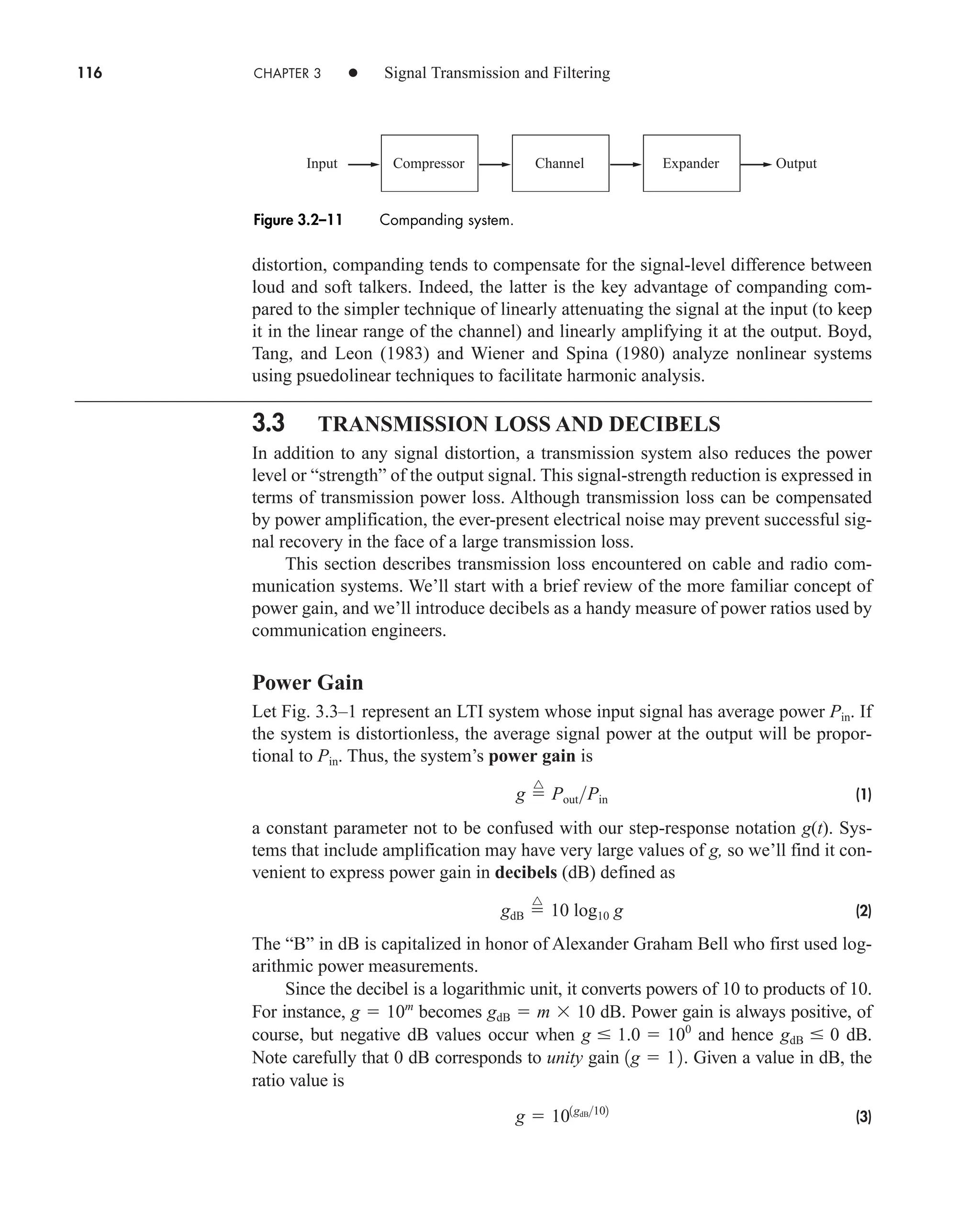

expander at the output, as shown in Fig. 3.2–11.

A compressor has greater amplification at low signal levels than at high signal lev-

els, similar to Fig. 3.2–10, and thereby compresses the range of the input signal. If the

compressed signal falls within the linear range of the channel, the signal at the channel

output is proportional to Tcomp[x(t)] which is distorted by the compressor but not the chan-

nel. Ideally, then, the expander has a characteristic that perfectly complements the com-

pressor so the expanded output is proportional to Texp{Tcomp[x(t)]} x(t), as desired.

The joint use of compressing and expanding is called companding (surprise?)

and is of particular value in telephone systems. Besides reducing nonlinear

v1t cos v2t

Second-harmonic distortion `

a22 a44 p

a1 3a34 p ` 100%

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 115](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-137-2048.jpg)

![146 CHAPTER 3 • Signal Transmission and Filtering

Pattern Recognition

Cross-correlation can be used in pattern recognition tasks. If the cross-correlation of ob-

jects A and B is similar to the autocorrelation of A, then B is assumed to match A. Oth-

erwise B does not match A. For example, the autocorrelation of x(t) (t) can be

found from performing the graphical correlation in Eq. (14b) as Rx(t) (t). If we ex-

amine the similarity of y(t) 2 (t) to x(t) by finding the cross-correlation Rxy(t)

2 (t), we see that Rxy(t) is just a scaled version of Rx(t). Therefore y(t) matches x(t).

However, if we take the cross-correlation of z(t) u(t) with x(t), we obtain

and conclude that z(t) doesn’t match x(t)

This type of graphical correlation is particularly effective for signals that do not

have a closed-form solution. For example, autocorrelation can find the pitch (funda-

mental frequency) of speech signals. The cross-correlation can determine if two speech

samples have the same pitch, and thus may have come from the same individual.

Let v(t) A[u(t) u(t D)] and w(t) v(t td). Use Eq. (16) with z(t) w*(t)

to sketch Rvw(t). Confirm from your sketch that and that

at .

We next investigate system analysis in the “ domain,” as represented by

Fig. 3.6–1. A signal x(t) having known autocorrelation is applied to an LTI sys-

tem with impulse response h(t), producing the output signal

We’ll show that the input-output cross-correlation function is

(18)

and that the output autocorrelation function is

(19a)

Substituting Eq. (18) into (19a) then gives

(19b)

Note that these t-domain relations are convolutions, similar to the time-domain relation.

Ry1t2 h*1t2 * h1t2 * Rx1t2

Ry1t2 h*1t2 * Ryx1t2

q

q

h*1m2Ryx 1t m2 dm

Ryx1t2 h1t2 * Rx1t2

q

q

h1l2 Rx1t l2 dl

y1t2 h1t2 * x1t2

q

q

h1l2 x1t l2 dl

Rx1t2

t

t td

0Rvw1t2 0max

2

EvEw

0Rvw1t2 02

EvEw

Rxz1t2 •

1 for t 6 12

12 t for 12 t 12

0 for t 7 12

EXAMPLE 3.6–2

EXERCISE 3.6–2

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 12/8/08 11:15 PM Page 146](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-168-2048.jpg)

![3.7 Questions and Problems 155

Express your answer in the form of y(t) Kx(t td). How does the

phase term affect the output time delays?

3.2–2 Do Prob. 3.2–1 with a system whose frequency response is What

is the effect of nonlinear phase distortion?

3.2–3 Show that a first-order lowpass system yields essentially distortionless

transmission if x(t) is bandlimited to .

3.2–4 Find and sketch y(t) when the test signal

, which approximates a triangular wave, is applied to a first-order

lowpass system with .

3.2–5* Find and sketch y(t) when the test signal from Prob. 3.2–4 is applied to a

first-order highpass system with and .

3.2–6 The signal 2 sinc 40t is to be transmitted over a channel with transfer

function H(f). The output is . Find H(f) and

sketch its magnitude and phase over .

3.2–7 Evaluate at , 0.5, 1, and 2 kHz for a first-order lowpass sys-

tem with kHz.

3.2–8 A channel has the transfer function

Sketch the phase delay and group delay . For what values of f

does ?

3.2–9 Consider a transmission channel with HC(f) (1 2a cos vT)ejvT

, which has

amplitude ripples. (a) Show that , so

theoutputincludesaleadingandtrailingecho.(b)Let and .

Sketch y(t) for and

3.2–10* Consider a transmission channel with HC(f ) exp[j(vT a sin vT)],

which has phase ripples. Assume and use a series expansion

to show that the output includes a leading and trailing echo.

3.2–11 Design a tapped-delay line equalizer for in Prob. 3.2–10 with

.

3.2–12 Design a tapped-delay line equalizer for in Prob. 3.2–9 with

.

3.2–13 Supposex(t)Acosv0tisappliedtoanonlinearsystemwithy(t)2x(t)–3x3

(t).

Write y(t) as a sum of cosines. Then evaluate the second-harmonic and third-

harmonic distortion when and .

A 2

A 1

a 0.4

Hc1 f 2

a 0.4

Hc1 f 2

a V p2

4T

3 .

t 2T

3

a 1

2

x1t2 ß1tt2

y1t2 ax1t2 x1t T2 ax1t 2T2

td1 f 2 tg1 f 2

tg1 f 2

td1 f 2

H1 f 2 µ

4ß a

f

40

bejpf30

for f 15 Hz

4ß a

f

40

bejp2

for f 7 15 Hz

B 2

f 0

td1 f 2

f 30

y1t2 20 sinc 140t 2002

B 3f0

H1 f 2 jf1B jf 2

B 3f0

4

25 cos 5v0t

x1t2 4 cos v0t 4

9 cos 3v0t

W V B

5ejv2

.

car80407_ch03_091-160.qxd 1/23/09 12:23 PM Page 155

Rev.Confirming Pages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-177-2048.jpg)

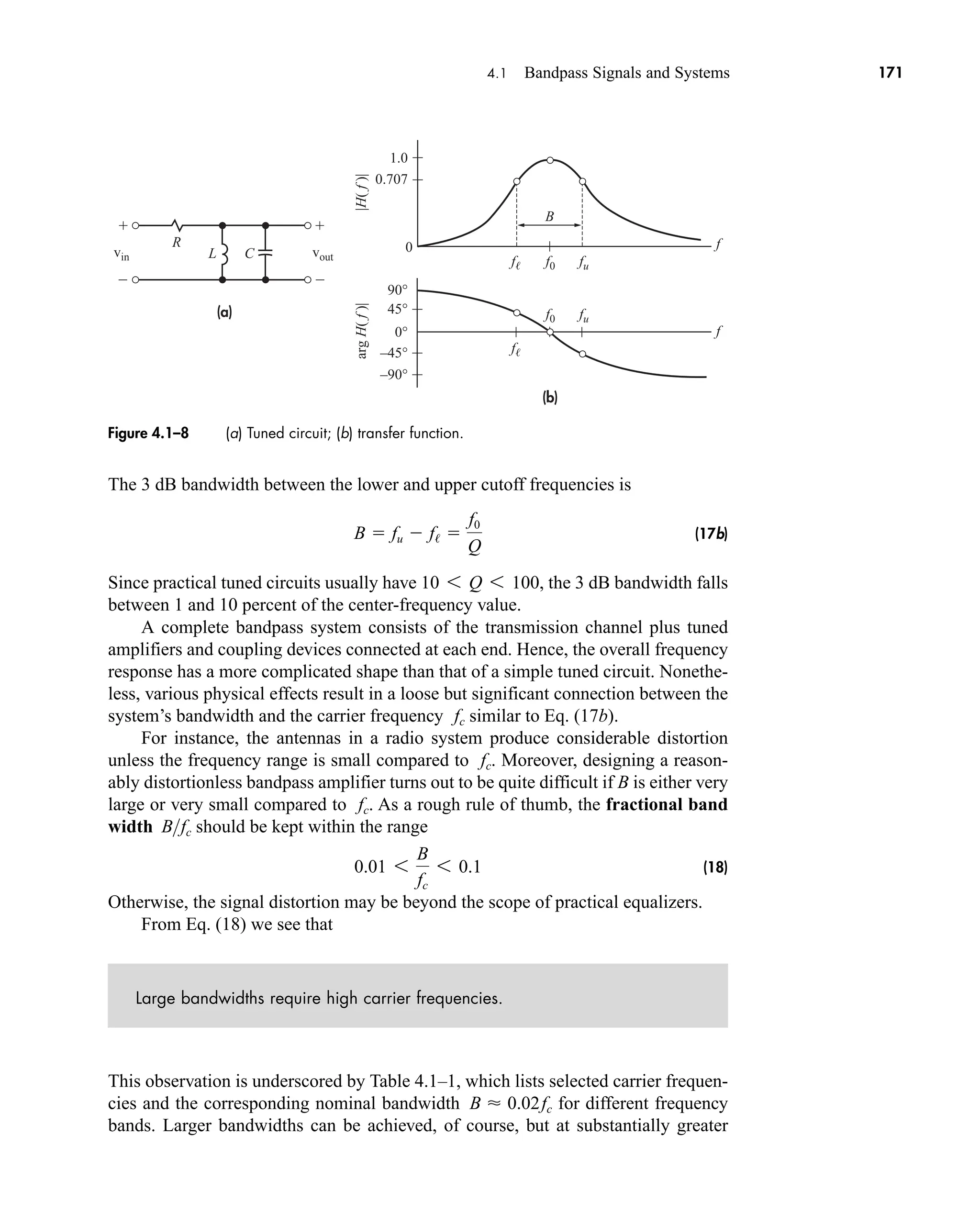

![Figure 4.1–6 (a) Bandpass system; (b) lowpass model.

(a) (b)

xbp(t) ybp(t) xp(t) yp(t)

Hbp( f ) Hp( f )

168 CHAPTER 4 • Linear CW Modulation

bandpass signals, we can keep the hermitian symmetry of in mind and use the

simpler expression

(13b)

which follows from Figs. 4.1–3a and 4.1–5.

Let and use 2 Re [z(t)] = z(t) + z*(t) to derive Eq. (13a) from Eq. (12).

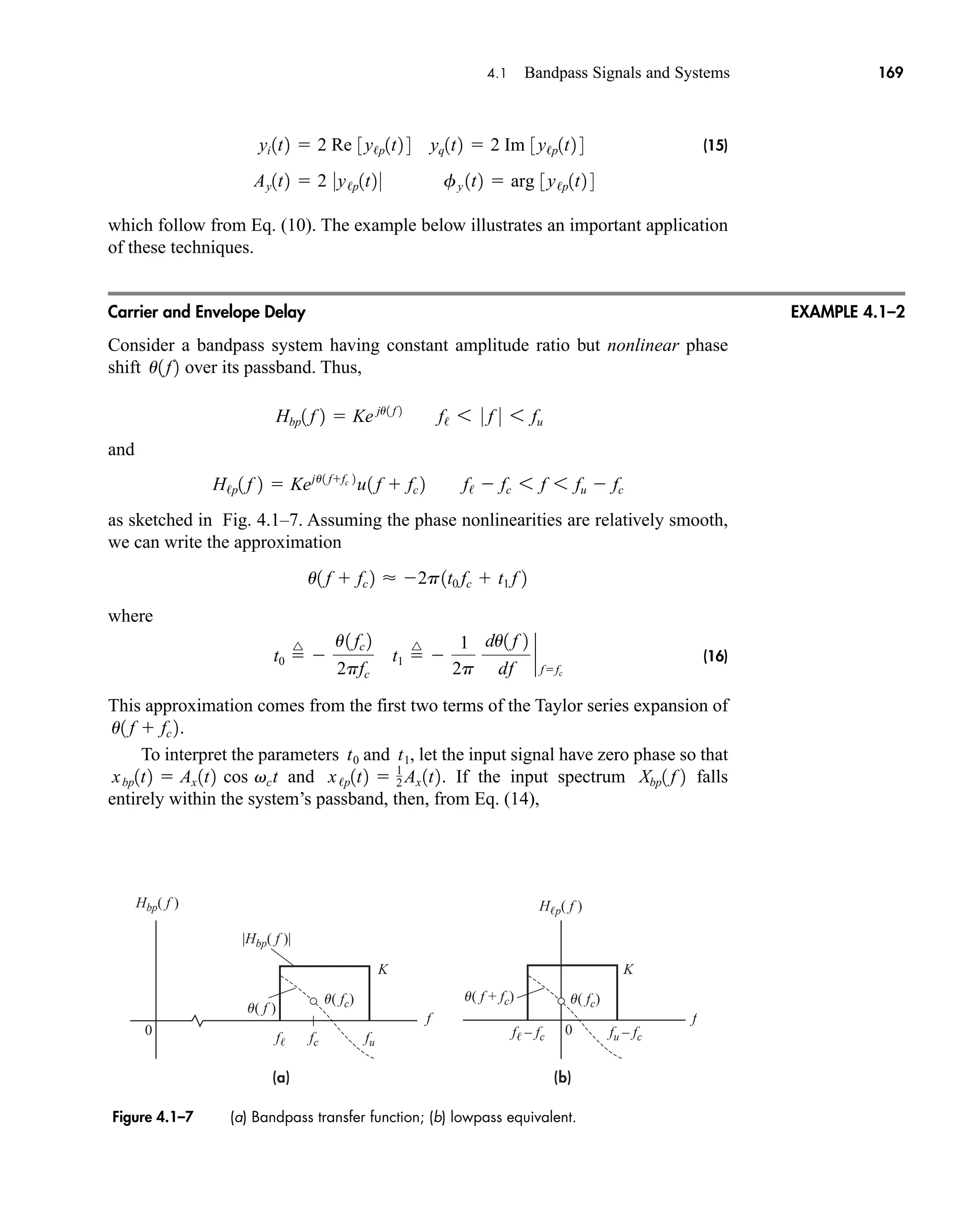

Bandpass Transmission

Now we have the tools needed to analyze bandpass transmission represented by

Fig. 4.1–6a where a bandpass signal applied to a bandpass system with transfer

function produces the bandpass output . Obviously, you could attempt

direct bandpass analysis via . But it’s usually easier to work

with the lowpass equivalent spectra related by

(14a)

where

(14b)

which is the lowpass equivalent transfer function.

Equation (14) permits us to replace a bandpass system with the lowpass equiva-

lent model in Fig. 4.1–6b. Besides simplifying analysis, the lowpass model provides

valuable insight to bandpass phenomena by analogy with known lowpass relation-

ships. We move back and forth between the bandpass and lowpass models with the

help of our previous results for bandpass signals.

In particular, after finding from Eq. (14), you can take its inverse Fourier

transform

The lowpass-to-bandpass transformation in Eq. (12) then yields the output signal

. Or you can get the output quadrature components or envelope and phase

immediately from as

y/p1t2

ybp1t2

y/p1t2 1

3Y/p1 f 2 4 1

3H/p1 f 2X/p1 f 2 4

Y/p1 f 2

H/p1 f 2 Hbp1 f fc 2u1 f fc 2

Y/p1 f 2 H/p1 f 2 X/p1 f 2

Ybp1 f 2 Hbp1 f 2Xbp1 f 2

ybp1t2

Hbp1 f 2

xbp1t2

z1t2 v/p1t2e jvct

Vbp1 f 2 V/p1 f fc 2 f 7 0

Vbp1 f 2

EXERCISE 4.1–1

car80407_ch04_161-206.qxd 1/15/09 4:19 PM Page 168

Rev.Confirming Pages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-190-2048.jpg)

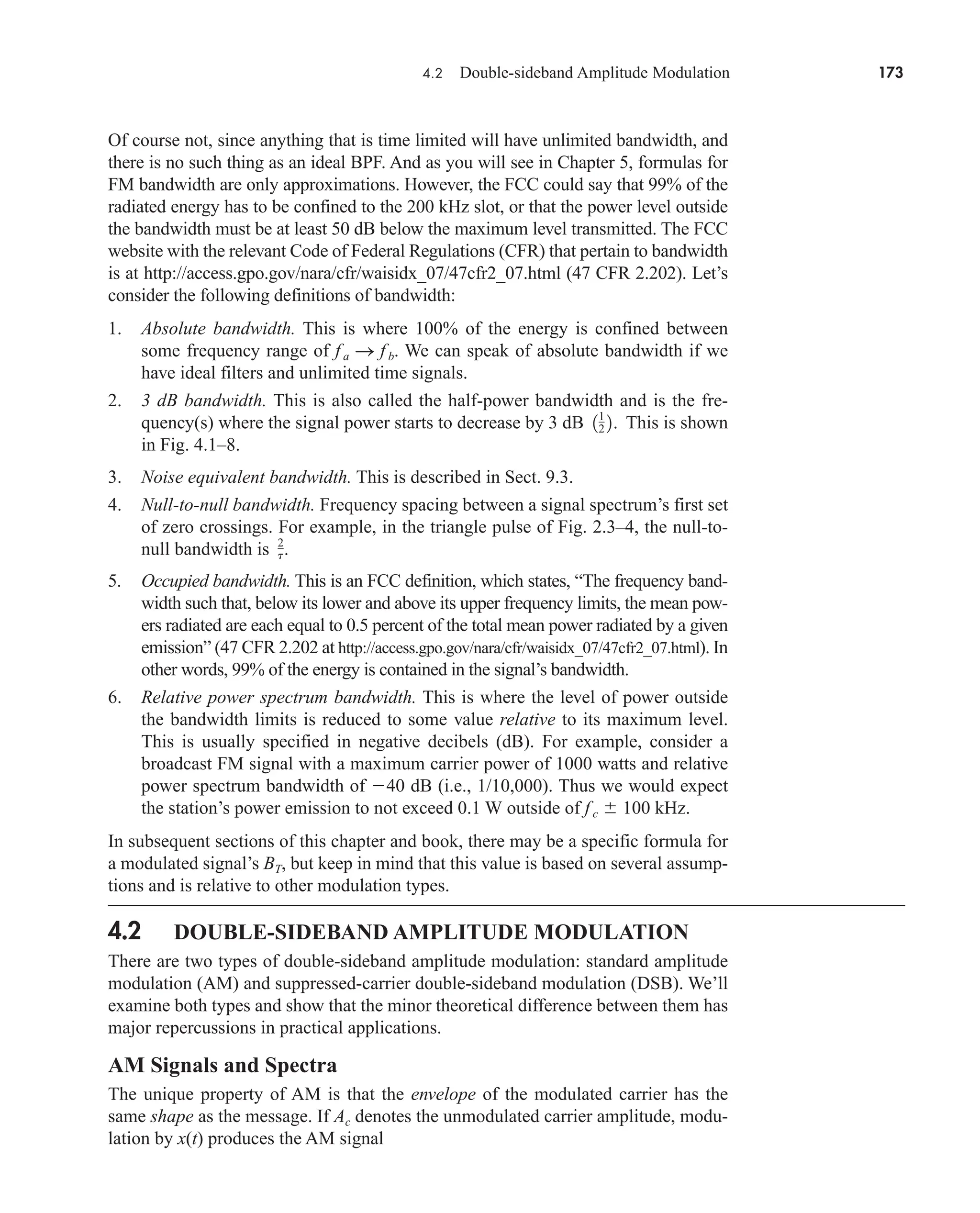

![fc + W

fc – W fc

a2d( f )

a1X( f )

a2[X( f ) * X( f )]

/2

1

a1d( f – fc)

a2X( f – fc)

/2

1

a2d( f – 2fc)

2fc

2W

0 W

/4

1

f

Figure 4.3–4 Spectral components in Eq. (1).

+

Ac cos vct

x(t)Ac cos vct

Ac [1 + x(t)] cos vct

x(t)

/2

1

/2

1

Ac [1 – x(t)] cos vct

/2

1

x(t)

/2

1

–

AM

mod

AM

mod

+

–

Figure 4.3–5 Balanced modulator.

+

–

xc(t)

x(t)

c(t)

vout

+

–

+

+–

–

BPF

Figure 4.3–6 Ring modulator.

4.3 Modulators and Transmitters 183

modulator can be thought of as multiplying x(t) and c(t). However because c(t) is a

periodic function, it can be represented by a Fourier series expansion. Thus

Observe that the DSB signal can be obtained by passing through a bandpass

filter having bandwidth 2W centered at . This modulator is often referred to as a

double-balanced modulator since it is balanced with respect to both x(t) and c(t).

A balanced modulator using switching circuits is discussed in Example 6.1–1

regarding bipolar choppers. Other circuit realizations can be found in the literature.

fc

vout1t2

vout1t2

4

p

x1t2 cos vct

4

3p

x1t2 cos 3vct

4

5p

x1t2 cos 5vct p

car80407_ch04_161-206.qxd 12/8/08 11:28 PM Page 183](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-205-2048.jpg)

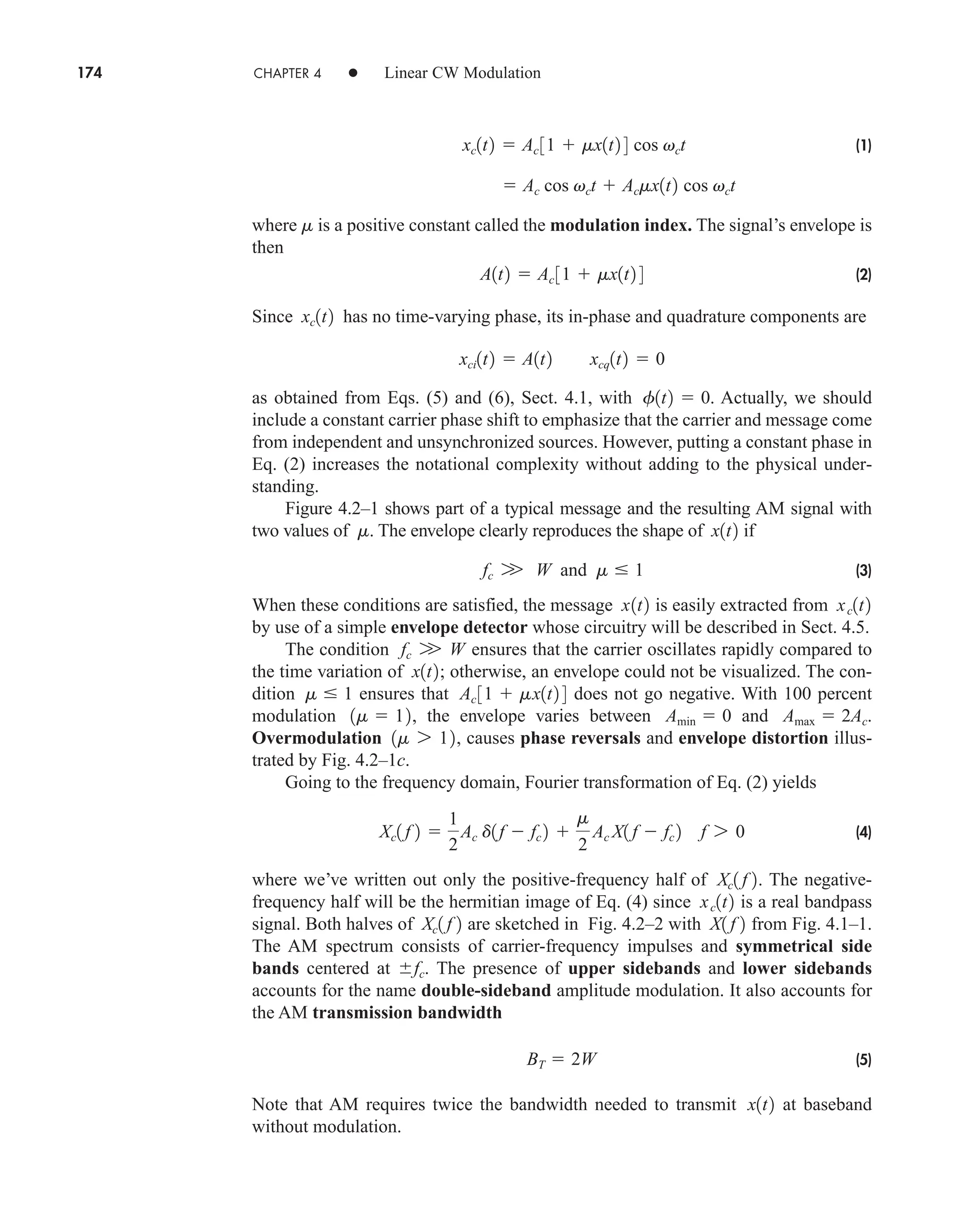

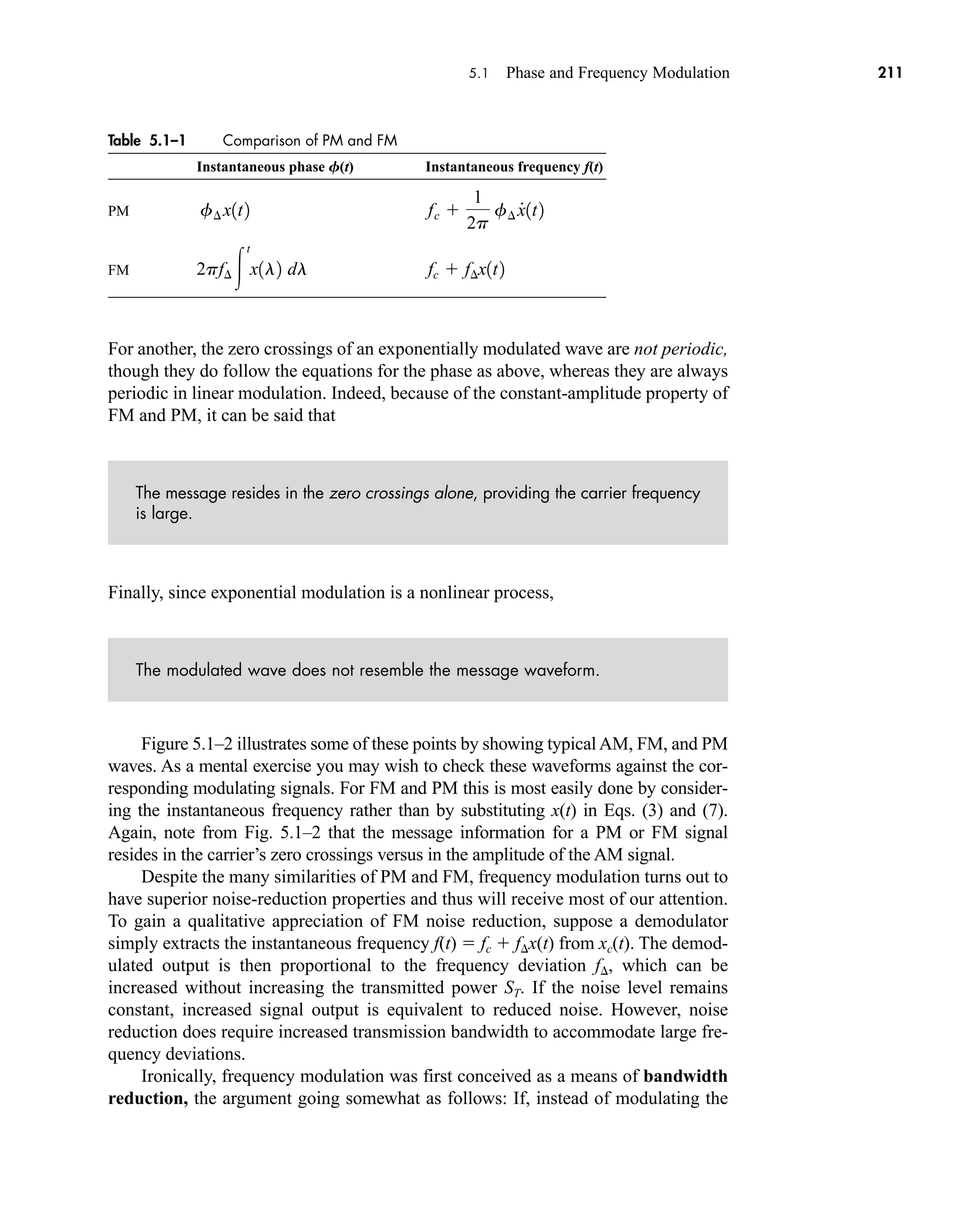

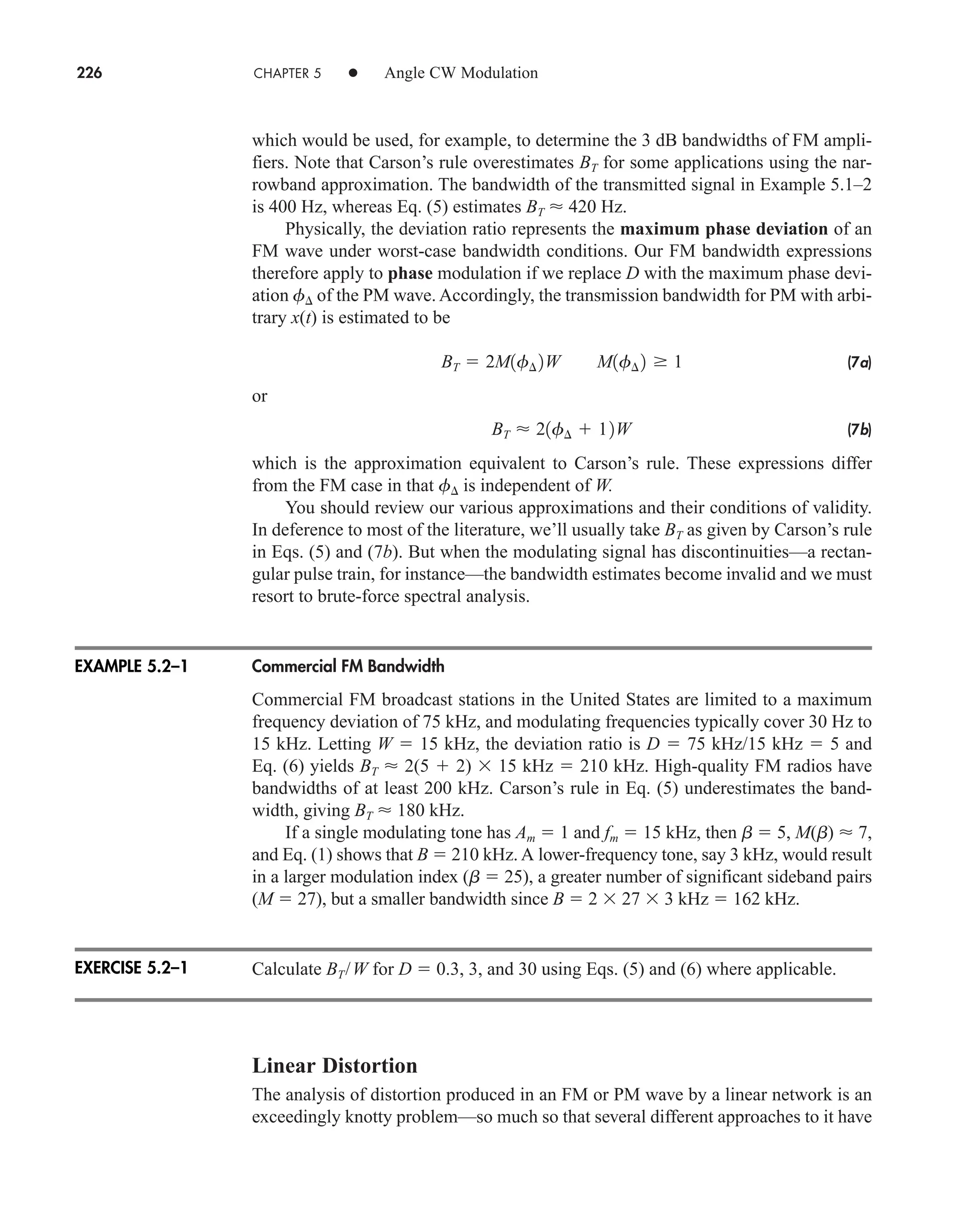

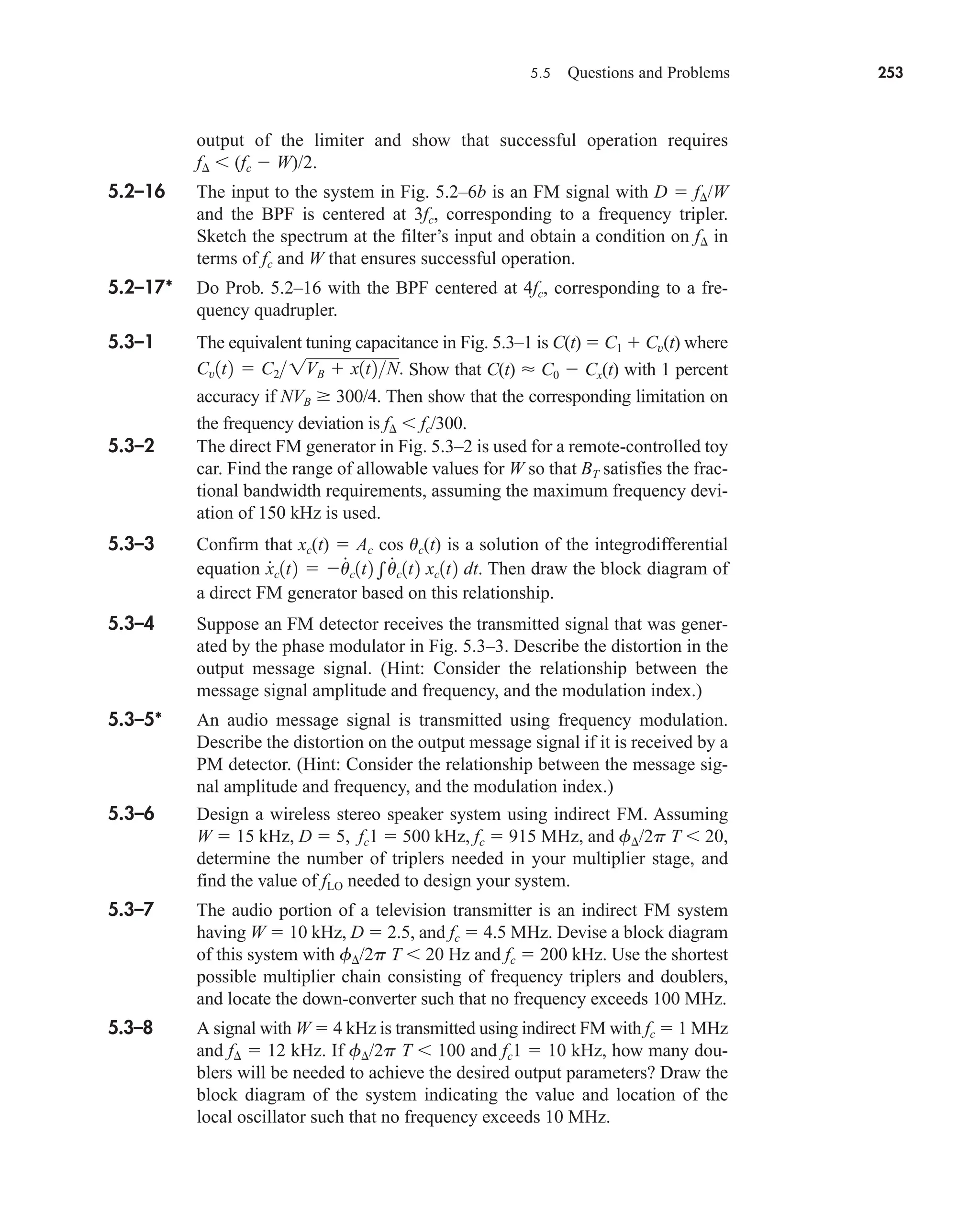

![AM

FM

PM

Modulating

signal

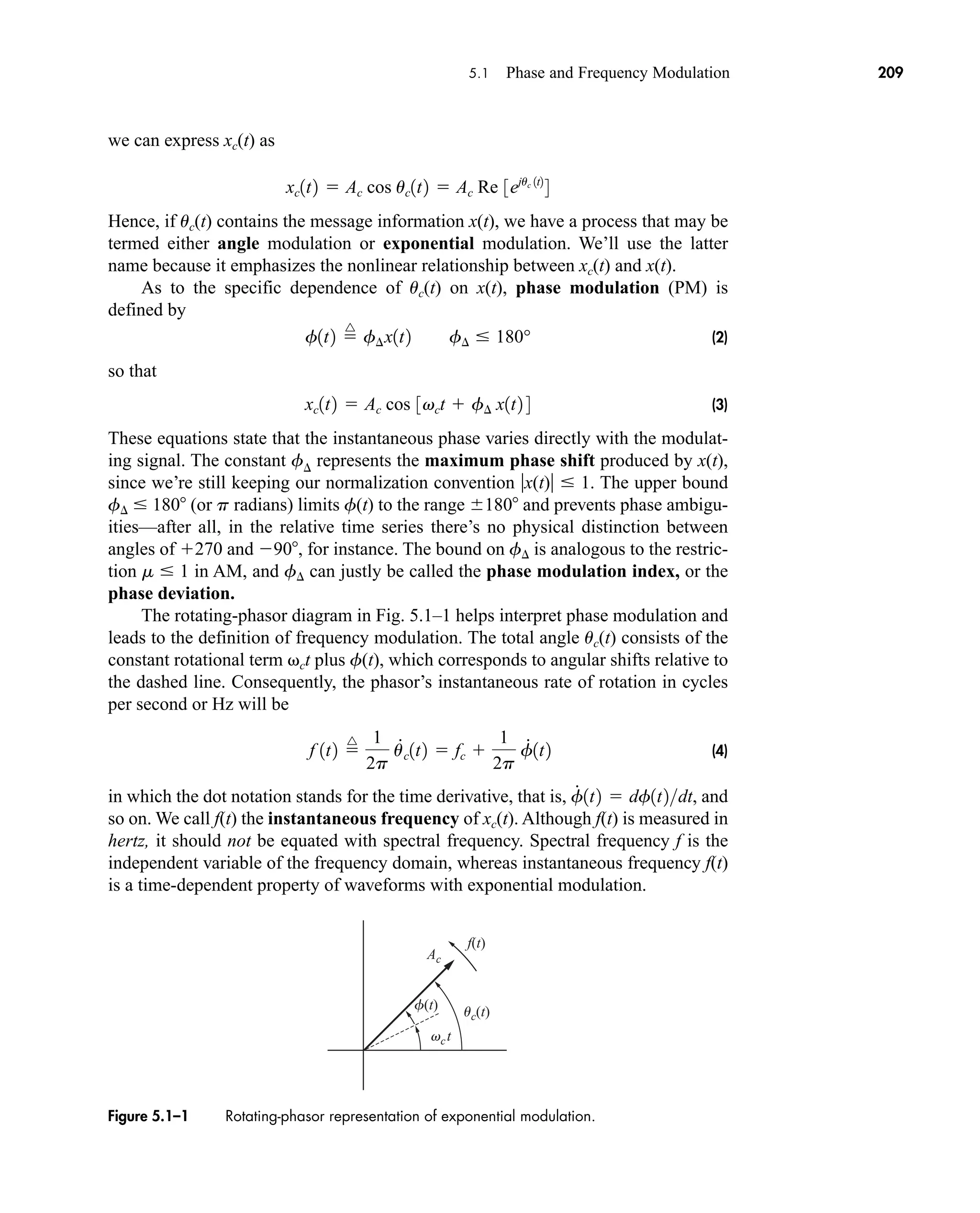

Figure 5.1–2 Illustrative AM, FM, and PM waveforms.

212 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

carrier amplitude, we modulate the frequency by swinging it over a range of, say,

50 Hz, then the transmission bandwidth will be 100 Hz regardless of the message

bandwidth. As we’ll soon see, this argument has a serious flaw, for it ignores the dis-

tinction between instantaneous and spectral frequency. Carson (1922) recognized

the fallacy of the bandwidth-reduction notion and cleared the air on that score.

Unfortunately, he and many others also felt that exponential modulation had no

advantages over linear modulation with respect to noise. It took some time to over-

come this belief but, thanks to Armstrong (1936), the merits of exponential modula-

tion were finally appreciated. Before we can understand them quantitatively, we

must address the problem of spectral analysis.

Suppose FM had been defined in direct analogy to AM by writing xc(t) Ac cos vc(t) t

with vc(t) vc[1 mx(t)]. Demonstrate the physical impossibility of this definition by

finding f(t) when x(t) cos vmt.

Narrowband PM and FM

Our spectral analysis of exponential modulation starts with the quadrature-carrier

version of Eq. (1), namely

(9)

where

(10)

xci1t2 Ac cos f1t2 Ac c1

1

2!

f2

1t2 p d

xc1t2 xci1t2 cos vct xcq1t2 sin vct

EXERCISE 5.1–1

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 212](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-234-2048.jpg)

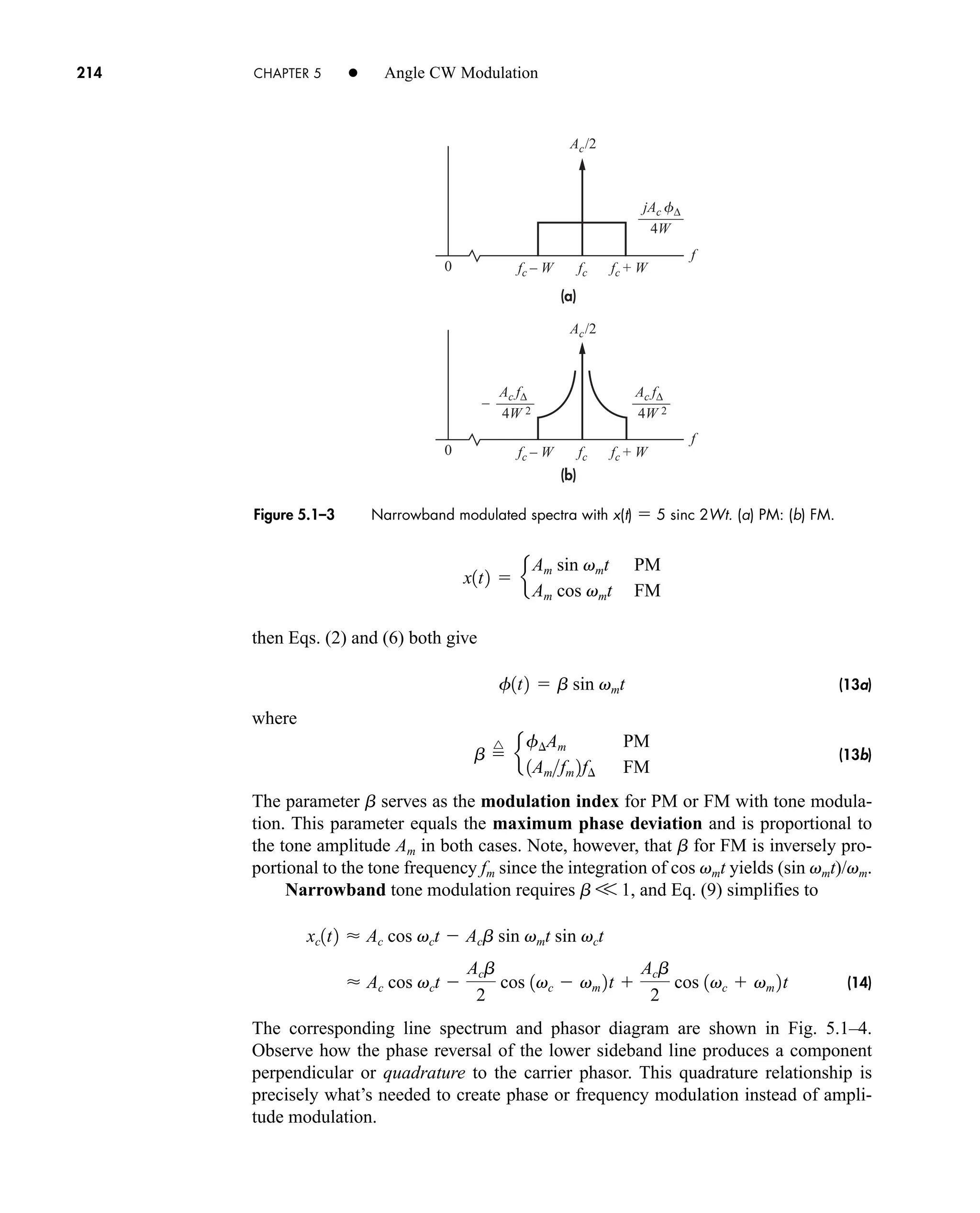

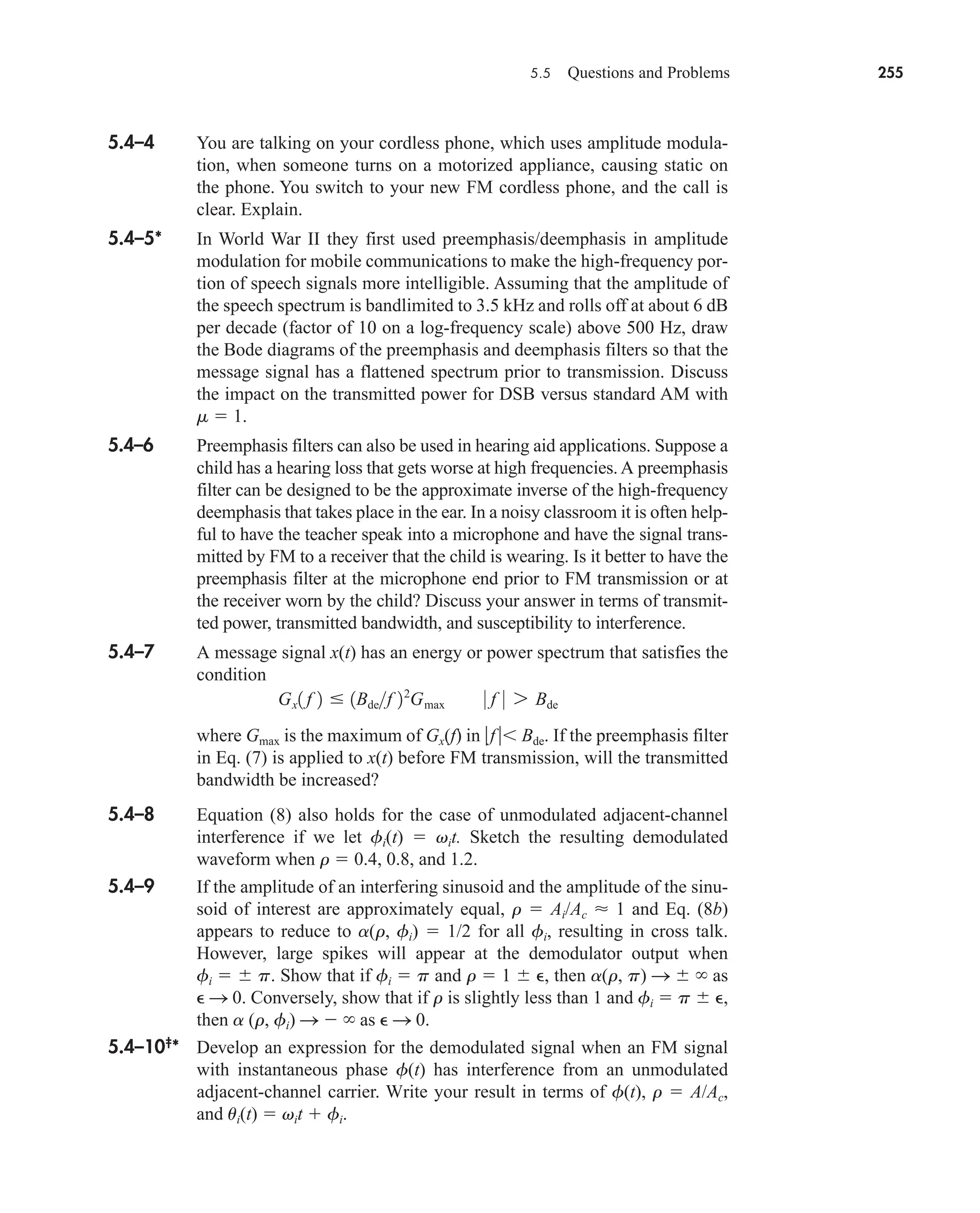

![(a) (b)

fc fc

Ac

2bfm

2bfm

Ac

b = 0.2

b = 1

b = 5

b = 10

5.1 Phase and Frequency Modulation 219

include the second-order pair of sideband lines that rotate at 2fm relative to the car-

rier and whose resultant is collinear with the carrier. While the second-order pair vir-

tually wipes out the undesired amplitude modulation, it also distorts f(t). The phase

distortion is then corrected by adding the third-order pair, which again introduces

amplitude modulation, and so on ad infinitum.

When all spectral lines are included, the odd-order pairs have a resultant in

quadrature with the carrier that provides the desired frequency modulation plus

unwanted amplitude modulation. The resultant of the even-order pairs, being

collinear with the carrier, corrects for the amplitude variations. The net effect is then

as illustrated in Fig. 5.1–8. The tip of the resultant sweeps through a circular arc

reflecting the constant amplitude Ac.

Tone Modulation With NBFM

The narrowband FM signal xc(t) 100 cos [2p 5000t 0.05 sin 2p 200t] is trans-

mitted. To find the instantaneous frequency f(t) we take the derivative of u(t)

5000 10 cos 2p 200 t

1

2p

32p 5000 0.0512p 2002 cos 2p 200 t4

f1t2

1

2p

u

#

1t2

Figure 5.1–7 Single-tone-modulated line spectra: (a) FM or PM with fm fixed; (b) FM with

Amf fixed.

EXAMPLE 5.1–2

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 219](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-241-2048.jpg)

![EXERCISE 5.1–3

Ac

Even-order

sidebands

Odd-order

sidebands

Figure 5.1–8 FM phasor diagram for arbitrary b.

220 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

From f(t) we determine that fc 5000 Hz, f 10, and x(t) cos 2p 200t. There

are two ways to find b. For NBFM with tone modulation we know that

f(t) b sin vmt. Since xc(t) Ac cos [vct f(t)], we can see that b 0.05. Alter-

natively we can calculate

From f(t) we find that Amf 10 and fm 200 so that b 10/200 0.05 just as

we found earlier. The line spectrum has the form of Fig. 5.1–4a with Ac 100 and

sidelobes Acb /2 2.5. The minor distortion from the narrowband approximation shows

up in the transmitted power. From the line spectrum we get

versus when there are

enough sidelobes so that there is no amplitude distortion.

Consider tone-modulated FM with Ac 100, Am f 8 kHz, and fm 4 kHz. Draw

the line spectrum for fc 30 kHz and for fc 11kHz.

Multitone and Periodic Modulation

The Fourier series technique used to arrive at Eq. (18) also can be applied to the case

of FM with multitone modulation. For instance, suppose that x(t) A1 cos v1t

A2 cos v2t, where f1 and f2 are not harmonically related. The modulated wave is first

written as

xc1t2 Ac 31cos a1 cos a2 sin a1 sin a2 2 cos vct

ST 1

2 Ac

2

1

2110022

5000

1

2 110022

1

2 12.522

5006.25

ST 1

2 12.522

b

Am

fm

f¢

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/15/08 10:04 PM Page 220](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-242-2048.jpg)

![5.2 Transmission Bandwidth and Distortion 229

ordinary sinusoid at frequency f(t) fc f x(t). For if the system’s response to a

carrier-frequency sinusoid is

and if xc(t) has a slowly changing instantaneous frequency f(t), then

(13)

It can be shown that this approximation requires the condition

(14)

in which for tone-modulated FM with fm W. If H(f) represents a

single-tuned bandpass filter with 3 dB bandwidth B, then the second term in Eq. (14)

equals 8/B2

and the condition becomes 4fW/B2

V 1 which is satisfied by the trans-

mission bandwidth requirement B BT.

Now suppose that Eq. (14) holds and the system has a nonlinear phase shift such

as arg H( f) af 2

, where a is a constant. Upon substituting

we get

Thus, the total phase in Eq. (13) will be distorted by the addition of and

Let H(f) 1 and arg H(f) 2pt1(f fc). Show that Eqs. (11) and (13) give the

same result with f(t) b sin vmt provided that vmt1 V p.

Nonlinear Distortion and Limiters

Amplitude distortion of an FM wave produces FM-to-AM conversion. Here we’ll

show that the resulting AM can be eliminated through the use of controlled

nonlinear distortion and filtering.

For purposes of analysis, let the input signal in Fig. 5.2–4 be

where uc(t) vct f(t) and A(t) is the amplitude. The nonlinear element is assumed

to be memoryless—meaning no energy storage—so the input and output are related

by an instantaneous nonlinear transfer characteristic vout T[vin]. We’ll also assume

for convenience that T[0] 0.

Although vin(t) is not necessarily periodic in time, it may be viewed as a

periodic function of uc with period 2p. (Try to visualize plotting vin versus uc with

vin1t2 A1t2 cos uc1t2

f

# 2

1t2.

f

#

1t2

arg H 3 f 1t2 4 a f c

2

a fc

p

f

#

1t2

a

4p2 f

#2

1t2

f1t2 fc f

#

1t22p

0 f

.

.

1t2 0 4p2

f¢W

0f

..

1t20max `

1

H1 f 2

d2

H1 f 2

df 2 `

max

V 8p2

yc1t2 AcH3f 1t2 4 cos 5vct f1t2 arg H3f 1t2 46

yc1t2 AcH1fc 2 cos 3vct arg H1fc 2 4

EXERCISE 5.2–2

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 1/13/09 4:03 PM Page 229

Rev.Confirming Pages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-251-2048.jpg)

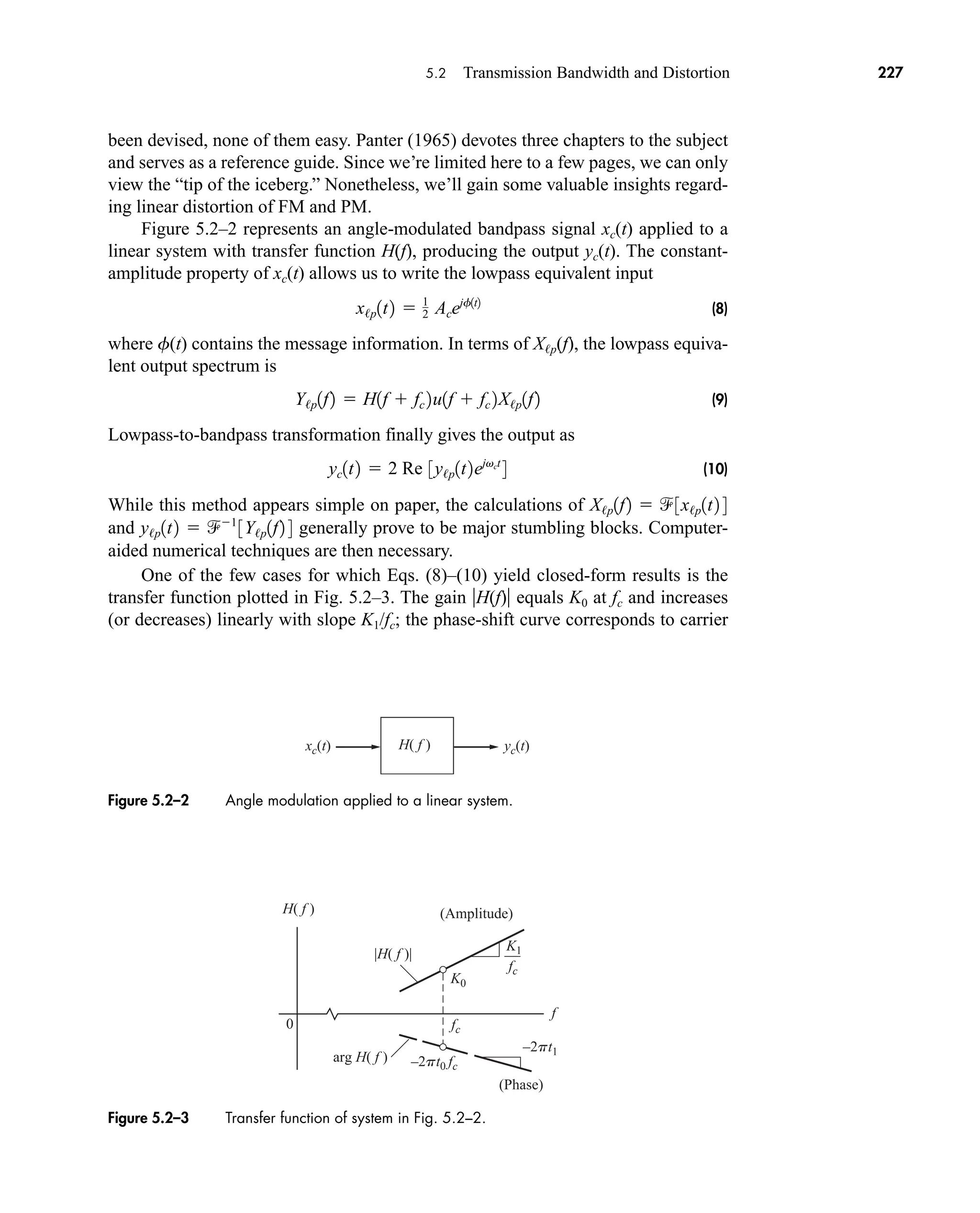

![vin(t) vout(t) = T [vin(t)]

Nonlinear element

Figure 5.2–4 Nonlinear system to reduce envelope variations (AM).

230 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

time held fixed.) Likewise, the output is a periodic function of uc and can be

expanded in the trigonometric Fourier series

(15a)

where

(15b)

The time variable t does not appear explicitly here, but vout depends on t via the time-

variation of uc. Additionally, the coefficients an may be functions of time when the

amplitude of vin has time variations.

But we’ll first consider the case of an undistorted FM input, so A(t) equals the

constant Ac and all the an are constants. Hence, writing out Eq. (15a) term by term

with t explicitly included, we have

(16)

This expression reveals that the nonlinear distortion produces additional FM waves

at harmonics of the carrier frequency, the nth harmonic having constant amplitude

2an and phase modulation nf(t) plus a constant phase shift arg an.

If these waves don’t overlap in the frequency domain, the undistorted input

can be recovered by applying the distorted output to a bandpass filter. Thus, we

say that FM enjoys considerable immunity from the effects of memoryless nonlin-

ear distortion.

Now let’s return to FM with unwanted amplitude variations A(t). Those varia-

tions can be flattened out by an ideal hard limiter or clipper whose transfer char-

acteristic is plotted in Fig. 5.2–5a. Figure 5.2–5b shows a clipper circuit that uses a

comparator or high-gain operational amplifier such that any input voltages greater

or less than zero cause the output to reach either the positive or negative power sup-

ply rails.

The clipper output looks essentially like a square wave, since T[vin] V0 sgn vin

and

vout e

V0 vin 7 0

V0 vin 6 0

p

02a2 0 cos 32vc t 2f1t2 arg a2 4

vout1t2 02a1 0 cos 3vc t f1t2 arg a1 4

an

1

2p 2p

T 3vin 4ejnuc

duc

vout a 0

q

n1

2an 0 cos 1n uc arg an 2

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/15/08 10:04 PM Page 230](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-252-2048.jpg)

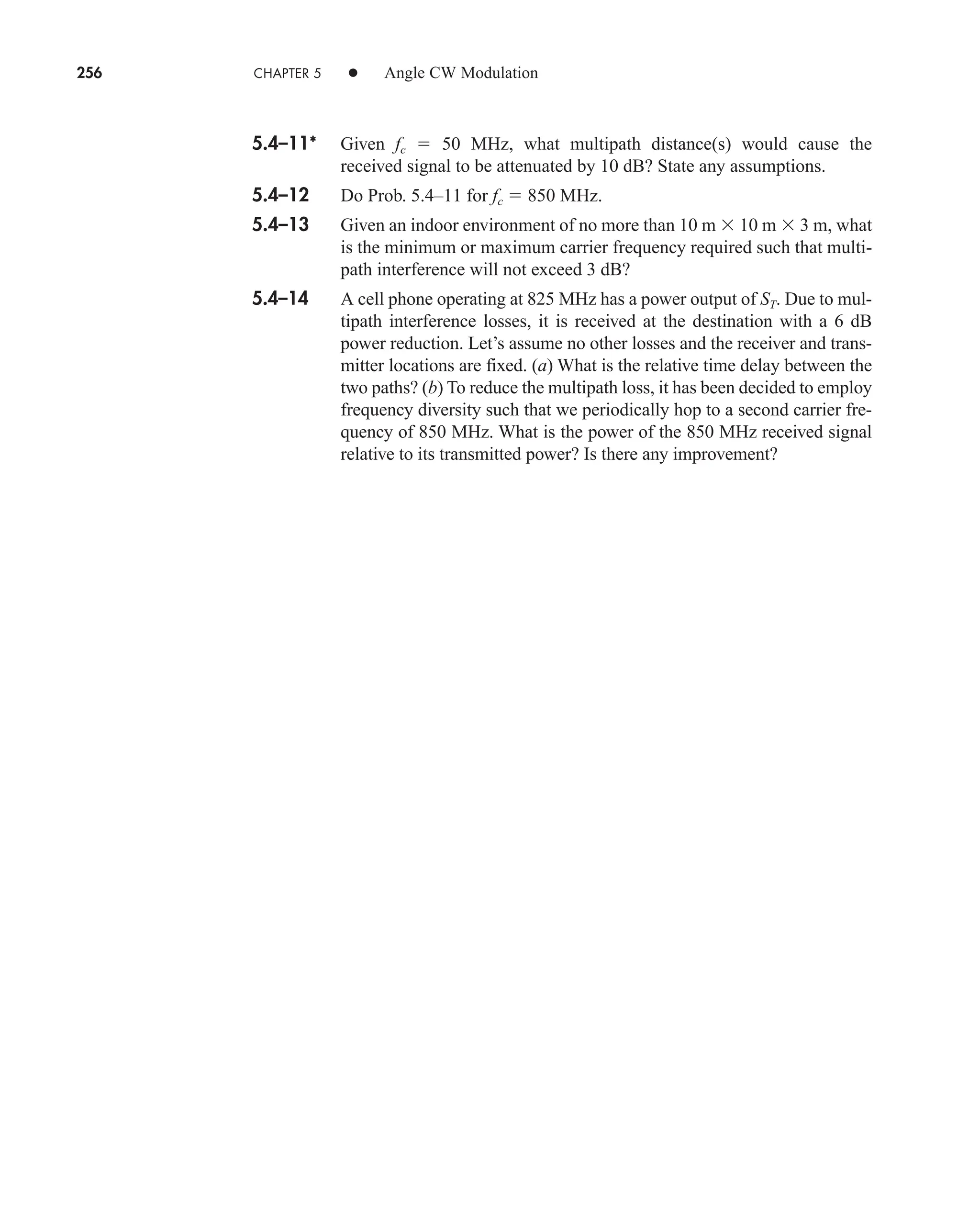

![(a)

(b)

A(t) cos [vct + f(t)]

Ac cos [vct + f(t)]

cos [vct + f(t)]

|2an| cos [nvct + nf(t) + arg an]

4V0

BPF

at fc

BPF

at n fc

p

(a) (b)

vin

vin

vout

vin

+ V0 + +

+

−

−

−

– V0

0

Figure 5.2–5 Hard limiter: (a) transfer characteristic; (b) circuit realization with Zener diodes.

5.2 Transmission Bandwidth and Distortion 231

Figure 5.2–6 Nonlinear processing circuits: (a) amplitude limiter; (b) frequency multiplier.

The coefficients are then found from Eq. (15b) to be

which are independent of time because the amplitude A(t) 0 does not affect the

sign of vin. Therefore,

(17)

and bandpass filtering yields a constant-amplitude FM wave if the components of

vout(t) have no spectral overlap. Incidentally, this analysis lends support to the previ-

ous statement that the message information resides entirely in the zero-crossings of

an FM or PM wave.

Figure 5.2–6 summarizes our results. The limiter plus BPF in part a removes

unwanted amplitude variations from an AM or PM wave, and would be used in a

receiver. The nonlinear element in part b distorts a constant-amplitude wave, but the

BPF passes only the undistorted term at the nth harmonic. This combination acts as

a frequency multiplier if n 1, and is used in certain types of transmitters.

vout1t2

4V0

p

cos3vct f1t2 4

4V0

3p

cos 33vct 3f1t2 4 p

an •

2V0pn n 1, 5, 9, p

2V0pn n 3, 7, 11, p

0 n 2, 4, 6, p

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 1/19/09 10:15 AM Page 231

Rev.Confirming Pages](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-253-2048.jpg)

![(b)

(a)

xΛ(t)

v(t) = 2 uc(t)

= 4[ fc + f∆x(t)]

∫

uc

xΛ

1

0

Schmitt trigger

Electronic switch

–1

–1

–2

p 3p/2

–p/2 2p

•

p

238 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

which is readily derived from the message waveform x(t). The system consists of an

analog inverter, an integrator, and a Schmitt trigger controlling an electronic switch.

The trigger puts the switch in the upper position whenever x(t) increases to 1 and

puts the switch in the lower position whenever x(t) decreases to 1.

Suppose the system starts operating at t 0 with x(0) 1 and the switch in

the upper position. Then, for 0 t t1,

so x(t) traces out the downward ramp in Fig. 5.3–6a until time t1 when x(t1) 1,

corresponding to uc(t1) p. Now the trigger throws the switch to the lower position

and

so x(t) traces out the upward ramp in Fig. 5.3–6a. The upward ramp continues until

time t2 when uc(t2) 2p and x(t2) 1. The switch then triggers back to the upper

position, and the operating cycle goes on periodically for t t2.

3

2

p

uc1t2 t1 6 t 6 t2

x¶1t2 1

t

t1

v1l2 dl 1

2

p

3uc1t2 uc1t1 2 4

1

2

p

uc1t2 0 6 t 6 t1

x¶1t2 1

t

0

v1l2 dl 1

2

p

3uc1t2 uc102 4

Figure 5.3–6 Triangular-wave FM: (a) waveform; (b) modulation system.

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 238](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-260-2048.jpg)

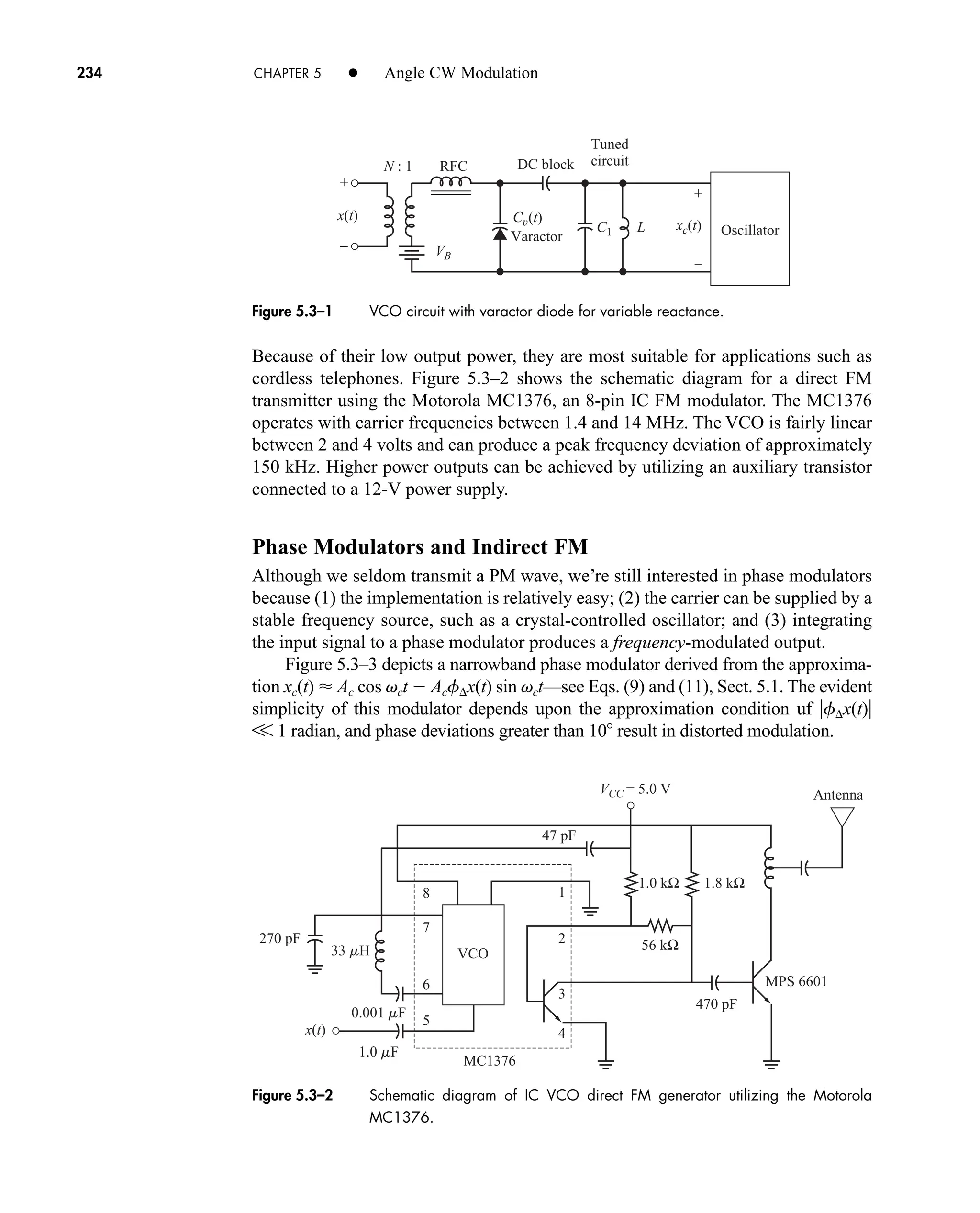

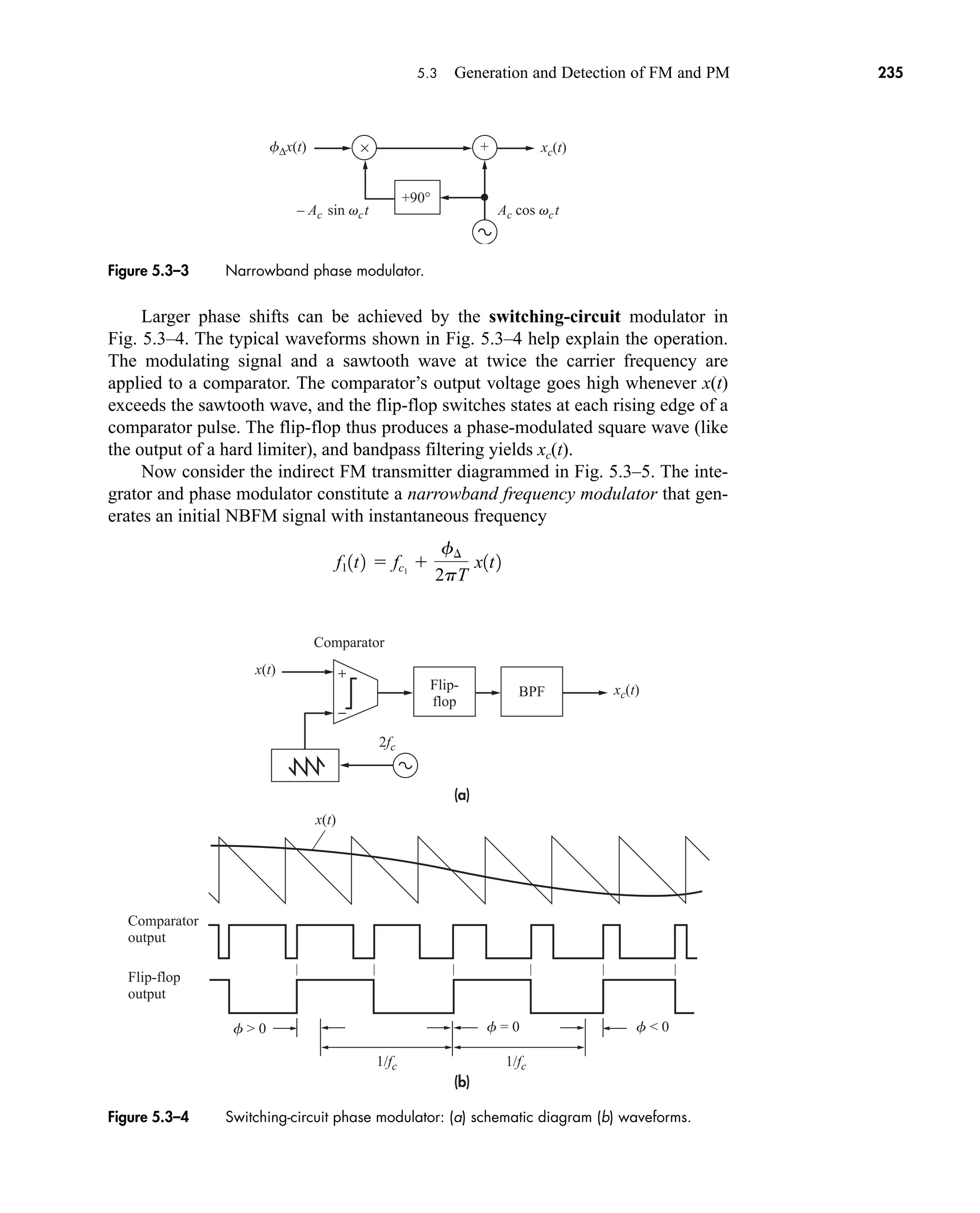

![5.3 Generation and Detection of FM and PM 239

A sinusoidal FM wave is obtained from x(t) using a nonlinear waveshaper with

transfer characteristics T[x(t)] Ac sin [(p/2)x(t)], which performs the inverse of

Eq. (5a). Or x(t) can be applied to a hard limiter to produce square-wave FM. A

laboratory test generator might have all three outputs available.

Frequency Detection

A frequency detector, often called a discriminator, produces an output voltage that

should vary linearly with the instantaneous frequency of the input. There are perhaps

as many different circuit designs for frequency detection as there are designers who

have considered the problem. However, almost every circuit falls into one of the fol-

lowing four operational categories:

1. FM-to-AM conversion

2. Phase-shift discrimination

3. Zero-crossing detection

4. Frequency feedback

We’ll look at illustrative examples from the first three categories, postponing fre-

quency feedback to Sect. 7.3. Analog phase detection is not discussed here because

it’s seldom needed in practice and, if needed, can be accomplished by integrating the

output of a frequency detector.

Any device or circuit whose output equals the time derivative of the input pro-

duces FM-to-AM conversion. To be more specific, let xc(t) Ac cos uc(t) with

then

(6)

Hence, an envelope detector with input yields an output proportional to

f(t) fc fx(t).

Figure 5.3–7a diagrams a conceptual frequency detector based on Eq. (6). The dia-

gram includes a limiter at the input to remove any spurious amplitude variations from

xc(t) before they reach the envelope detector. It also includes a DC block to remove the

constant carrier-frequency offset from the output signal. Typical waveforms are

sketched in Fig. 5.3–7b taking the case of tone modulation. A LPF has been included

after the limiter to remove waveform discontinuities and thereby facilitate differentia-

tion. However with slope detection, filtering and differentiation occur in the same stage.

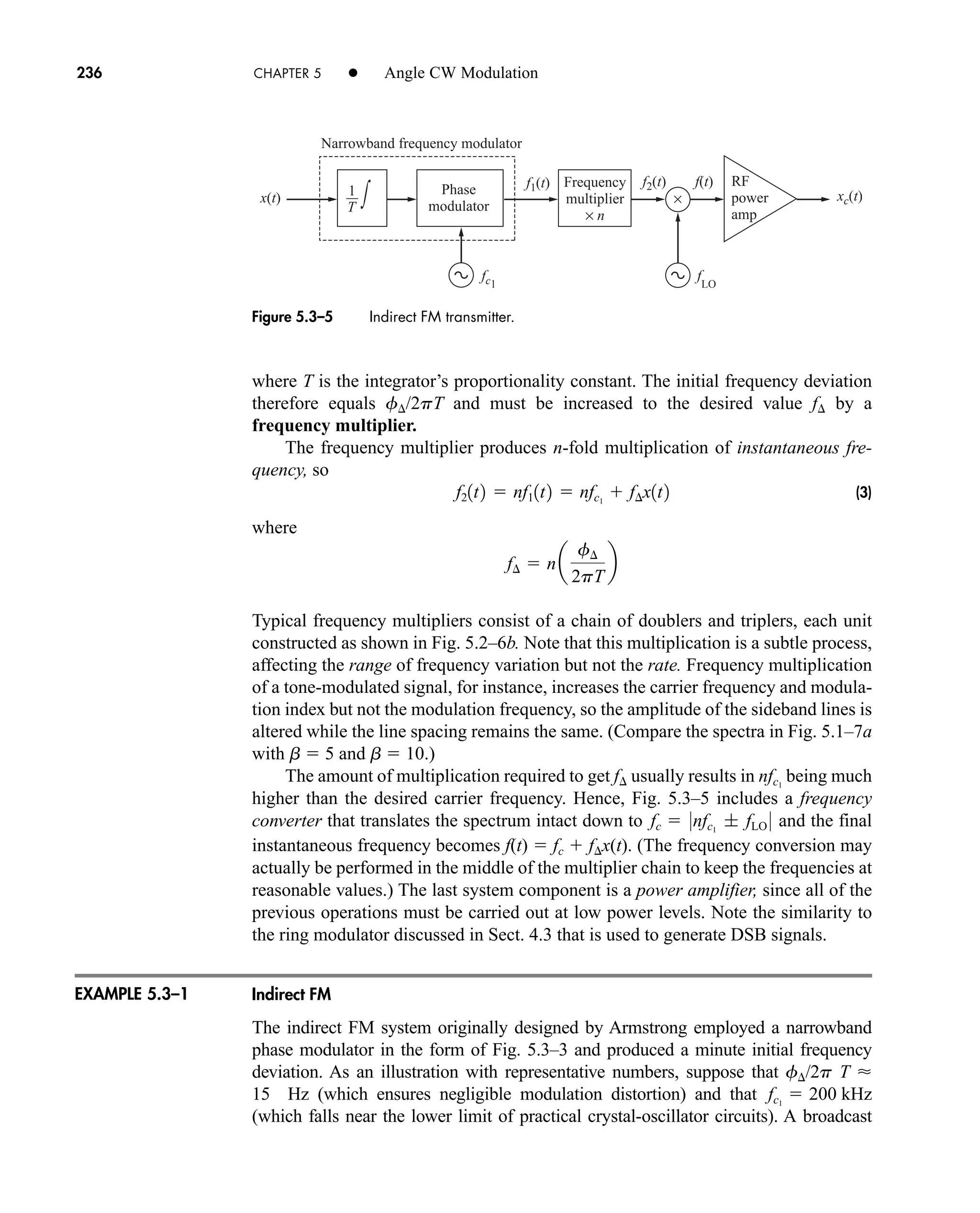

For actual hardware implementation of FM-to-AM conversion, we draw upon the

fact that an ideal differentiator has . Slightly above or below resonance,

the transfer function of an ordinary tuned circuit shown in Fig. 5.3–8a approximates

the desired linear amplitude response over a small frequency range. Thus, for

instance, a detuned AM receiver will roughly demodulate FM via slope detection.

Extended linearity is achieved by the balanced discriminator circuit in

Fig. 5.3–8b. A balanced discriminator includes two resonant circuits, one tuned

above fc and the other below, and the output equals the difference of the two

0H1 f 2 0 2pf

x

#

c1t2

2pAc 3fc f¢ x1t2 4 sin 3uc1t2 ; 180°4

.

xc1t2 Acu

.

c1t2 sin uc1t2

u

#

c1t2 2p3fc f¢x1t2 4;

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/15/08 10:04 PM Page 239](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-261-2048.jpg)

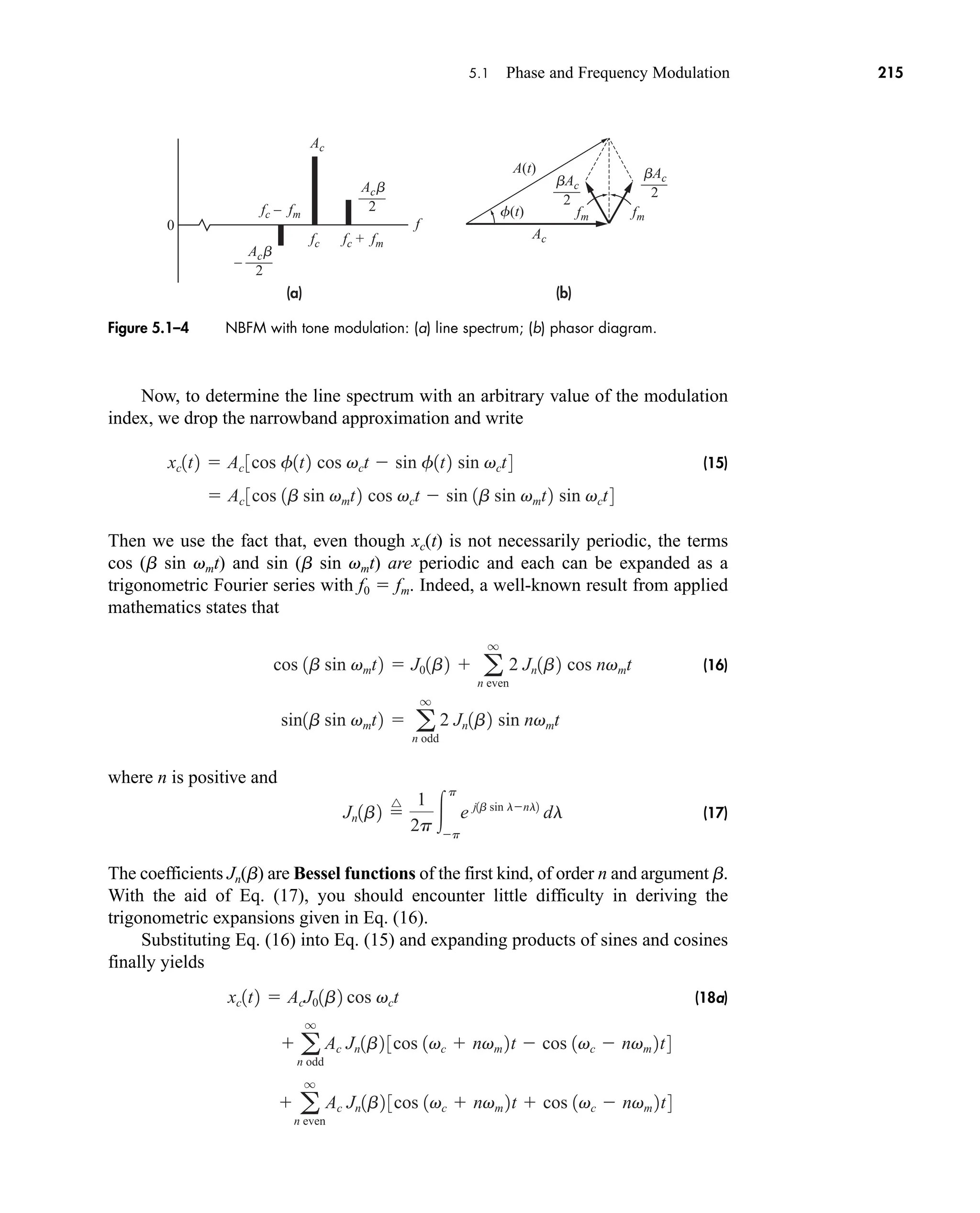

![(a)

(b)

(c)

Kx(t)

xc(t)

fc

fc

f0

f0 fc

f0 fc

f

f

Slope

approximation

|H( f )|

+

–

+

–

5.3 Generation and Detection of FM and PM 241

The term f(t t1) can be obtained with the help of a delay line or, equivalently, a

linear phase-shift network.

Figure 5.3–9 represents a phase-shift discriminator built with a network having

group delay t1 and carrier delay t0 such that vct0 90—which accounts for the

name quadrature detector. From Eq. (11), Sect. 5.2, the phase-shifted signal is pro-

portional to cos[vct 90 f(t t1)] sin [vct f(t t1)]. Multiplication by

cos [vct f(t)] followed by lowpass filtering yields an output proportional to

sin3f1t2 f1t t1 2 4 f1t2 f1t t1 2

Figure 5.3–8 (a) Slope detection with a tuned circuit; (b) balanced discriminator circuit;

(c) frequency-to-voltage characteristic.

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 241](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-263-2048.jpg)

![cos [vct + f(t)]

sin [vct + f(t – t1)]

xc(t) ×

Lim BPF LPF

Phase-shift

network

y

D(t) KD f∆x(t)

242 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

assuming t1 is small enough that f(t) f(t t1)V p. Therefore,

where the detection constant KD includes t1. Despite these approximations, a quadra-

ture detector provides better linearity than a balanced discriminator and is often

found in high-quality receivers.

Other phase-shift circuit realizations include the Foster-Seely discriminator

and the popular ratio detector. The latter is particularly ingenious and economical,

for it combines the operations of limiting and demodulation into one unit. See

Tomasi (1998, Chap. 7) for further details.

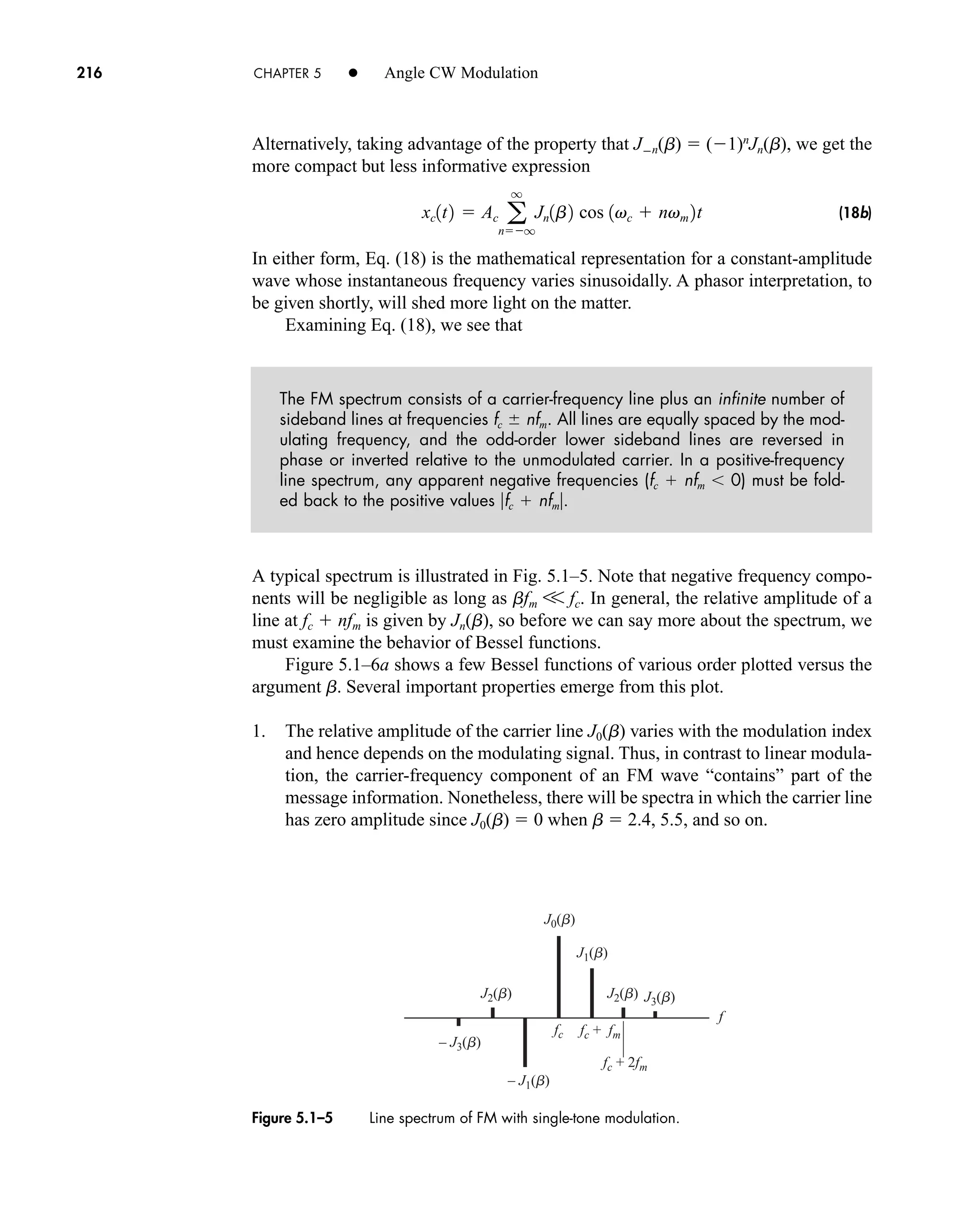

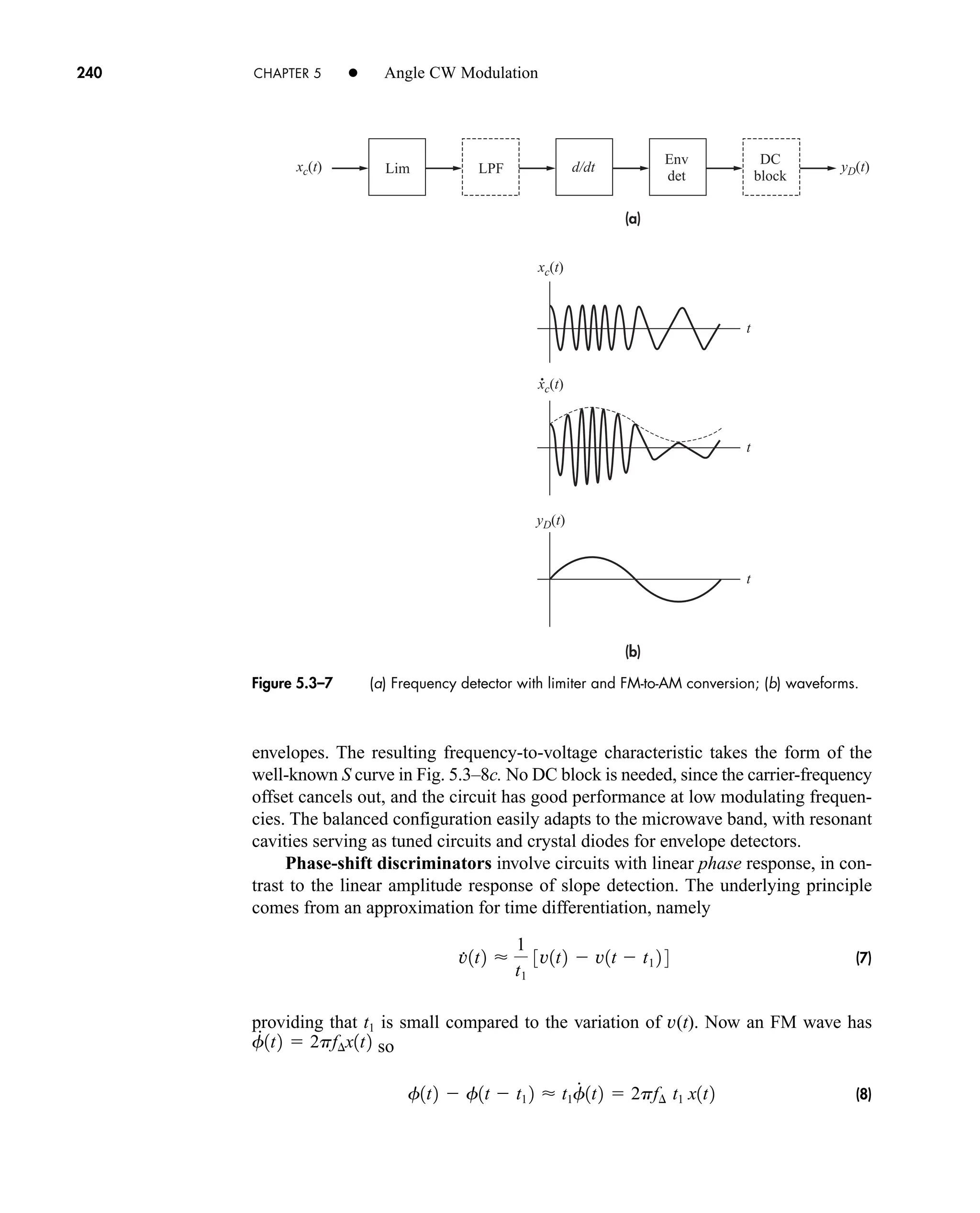

Lastly, Fig. 5.3–10 gives the diagram and waveforms for a simplified zero-

crossing detector. The square-wave FM signal from a hard limiter triggers a

monostable pulse generator, which produces a short pulse of fixed amplitude A and

duration t at each upward (or downward) zero crossing of the FM wave. If we invoke

the quasi-static viewpoint and consider a time interval T such that W V 1/T V fc,

the monostable output v(t) looks like a rectangular pulse train with nearly constant

period 1/f(t). Thus, there are nT Tf(t) pulses in this interval, and continually inte-

grating v(t) over the past T seconds yields

which becomes yD(t) KD fx(t) after the DC block.

Commercial zero-crossing detectors may have better than 0.1 percent linearity

and operate at center frequencies from 1 Hz to 10 MHz. A divide-by-ten counter

inserted after the hard limiter extends the range up to 100 MHz.

Today most FM communication devices utilize linear integrated circuits for FM

detection. Their reliability, small size, and ease of design have fueled the growth of

portable two-way FM and cellular radio communications systems. Phase-locked

loops and FM detection will be discussed in Sect. 7.3.

Given a delay line with time delay t0 V 1/fc, devise a frequency detector based on

Eqs. (6) and (7).

1

T

t

tT

v1l2 dl

1

T

nT At Atf 1t2

yD1t2 KDf¢x1t2

Figure 5.3–9 Phase-shift discriminator or quadrature detector.

EXERCISE 5.3–2

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 242](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-264-2048.jpg)

![(a)

(b)

xc(t)

T

v(t)

v(t) t

t – T

∫

t

t

Limiter

output

Hard

limiter

Monostable y

D(t)

––

T

1

t

DC

block

A

––

f(t)

1

5.4 Interference 243

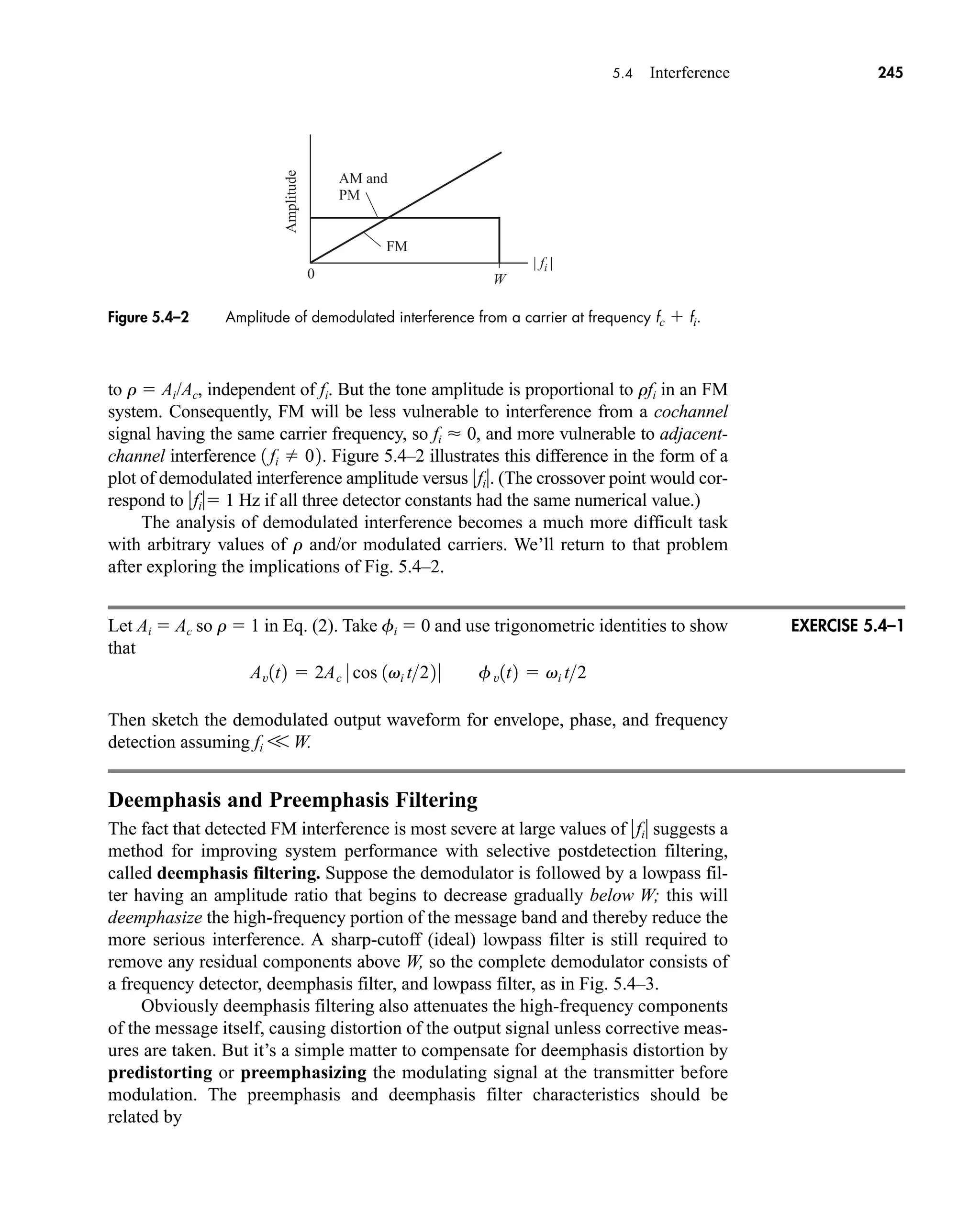

5.4 INTERFERENCE

Interference refers to the contamination of an information-bearing signal by another

similar signal, usually from a human source. This occurs in radio communication

when the receiving antenna picks up two or more signals in the same frequency

band. Interference may also result from multipath propagation, or from electromag-

netic coupling between transmission cables. Regardless of the cause, severe interfer-

ence prevents successful recovery of the message information.

Our study of interference begins with the simple but nonetheless informative

case of interfering sinusoids, representing unmodulated carrier waves. This simpli-

fied case helps bring out the differences between interference effects in AM, FM,

and PM. Then we’ll see how the technique of deemphasis filtering improves FM

performance in the face of interference. We conclude with a brief examination of the

FM capture effect.

Interfering Sinusoids

Consider a receiver tuned to some carrier frequency fc. Let the total received sig-

nal be

The first term represents the desired signal as an unmodulated carrier, while the sec-

ond term is an interfering carrier with amplitude Ai, frequency fc fi, and relative

phase angle fi.

To put v(t) in the envelope-and-phase form v(t) Av(t) cos [vct fv(t)], we’ll

introduce

(1)

r

^

AiAc ui1t2

^

vit fi

v1t2 Ac cos vc t Ai cos 31vc vi 2t fi 4

Figure 5.3–10 Zero-crossing detector: (a) diagram; (b) waveforms.

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 243](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-265-2048.jpg)

![Av(t)

fv(t) ui(t)

Ac r sin ui(t)

Ac [1 + r cos ui(t)]

Ac

rAc

244 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

Hence, Ai rAc and the phasor construction in Fig. 5.4–1 gives

(2)

These expressions show that interfering sinusoids produce both amplitude and phase

modulation. In fact, if r V 1 then

(3)

which looks like tone modulation at frequency fi with AM modulation index m r

and FM or PM modulation index b r. At the other extreme, if r 1 then

so the envelope still has tone modulation but the phase corresponds to a shifted car-

rier frequency fc fi plus the constant fi.

Next we investigate what happens when v(t) is applied to an ideal envelope,

phase, or frequency demodulator with detection constant KD. We’ll take the weak

interference case (r V 1) and use the approximation in Eq. (3) with fi 0. Thus,

the demodulated output is

(4)

provided that fi W—otherwise, the lowpass filter at the output of the demodulator

would reject fi W. The constant term in the AM result would be removed if the

demodulator includes a DC block. As written, this result also holds for synchronous

detection in DSB and SSB systems since we’ve assumed fi 0. The multiplicative

factor fi in the FM result comes from the instantaneous frequency deviation .

Equation (4) reveals that weak interference in a linear modulation system or phase

modulation system produces a spurious output tone with amplitude proportional

f

#

y1t22p

yD1t2 •

KD 11 r cos vit2 AM

KD r sin vit PM

KD r fi cos vit FM

fv1t2 vi t fi

Av1t2 Ai 31 r1

cos 1vi t fi 2 4

W

fv1t2 r sin 1vi t fi 2

Av1t2 Ac 31 r cos 1vi t fi 2 4

f v1t2 arctan

r sin ui1t2

1 r cos ui1t2

Av1t2 Ac 21 r2

2r cos ui1t2

Figure 5.4–1 Phasor diagram of interfering carriers.

car80407_ch05_207-256.qxd 12/8/08 10:49 PM Page 244](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/communicationsystemsanintro-a-241115060943-61721fa8/75/Communication_Systems__An_Intro_-_A-_Bruce_Carlson_-pdf-266-2048.jpg)

![252 CHAPTER 5 • Angle CW Modulation

5.2–3 What is the maximum frequency deviation for a FM system where

W 3 kHz and BT 30 kHz?

5.2–4 Do Prob. 5.2–3 with BT 10 kHz?

5.2–5 An FM system has f 10 kHz. Use Table 9.4–1 and Fig. 5.2–1 to estimate

the bandwidth for: (a) barely intelligible voice transmission; (b) telephone-

quality voice transmission: (c) high-fidelity audio transmission.

5.2–6 A video signal with W 5 MHz is to be transmitted via FM with

f 25 MHz. Find the minimum carrier frequency consistent with frac-

tional bandwidth considerations. Compare your results with transmis-

sion via DSB amplitude modulation.

5.2–7* Your new wireless headphones use infrared FM transmission and have a

frequency response of 30–15,000 Hz. Find BT and f consistent with

fractional bandwidth considerations, assuming fc 5 1014

Hz.

5.2–8 A commercial FM radio station alternates between music and talk

show/call-in formats. The broadcasted CD music is bandlimited to 15 kHz

based on convention. Assuming D 5 is used for both music and voice,

what percentage of the available transmission bandwidth is used during

the talk show if we take W 5 kHz for voice signals?

5.2–9 An FM system with f 30 kHz has been designed for W 10 kHz.

Approximately what percentage of BT is occupied when the modulating

signal is a unit-amplitude tone at fm 0.1, 1.0, or 5.0 kHz? Repeat your

calculations for a PM system with f 3 rad.

5.2–10 Consider phase-integral and phase-acceleration modulation defined in

Prob. 5.1–5. Investigate the bandwidth requirements for tone modula-

tion, and obtain transmission bandwidth estimates. Discuss your results.

5.2–11* The transfer function of a single-tuned BPF is H(f) 1/[1 j2Q (f fc)/fc]

over the positive-frequency passband. Use Eq. (10) to obtain an expression

for the output signal and its instantaneous phase when the input is an

NBPM signal.

5.2–12 Use Eq. (10) to obtain an expression for the output signal and its ampli-

tude when an FM signal is distorted by a system having H(f) K0

K3(f fc)3

over the positive-frequency passband.

5.2–13 Use Eq. (13) to obtain an expression for the output signal and its instan-

taneous frequency when an FM signal is distorted by a system having

H(f) 1 and arg H(f) a1(f fc) a3(f fc)3