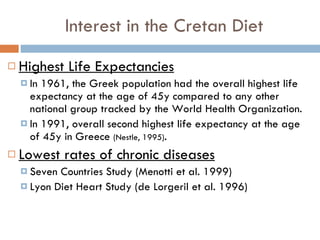

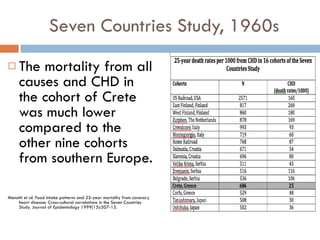

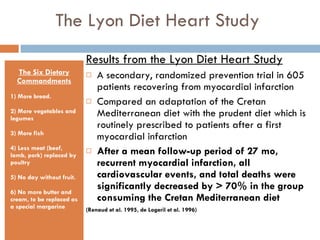

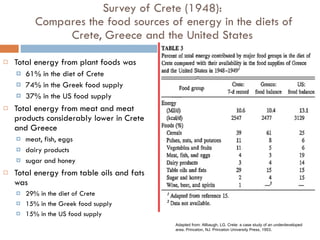

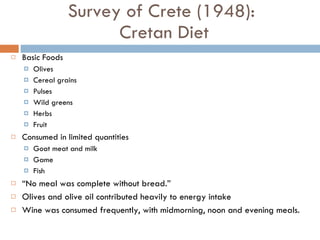

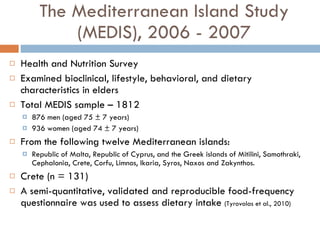

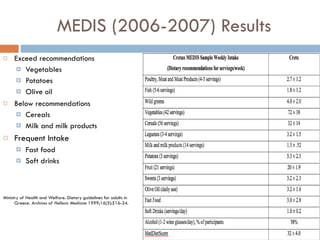

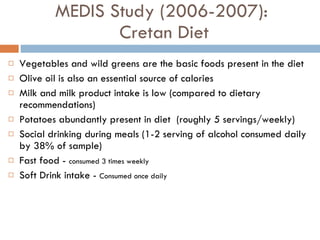

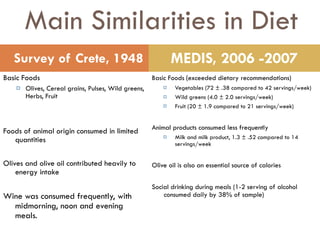

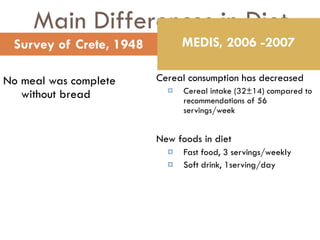

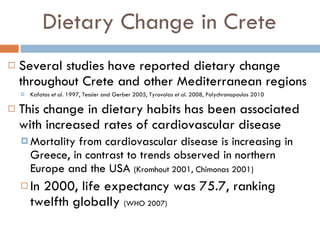

The document summarizes research on dietary changes in Crete, Greece over time. It compares data from a 1948 survey of the traditional Cretan diet to data from 2006-2007. The traditional Cretan diet was high in plant foods like olive oil, cereals, pulses, and vegetables. Animal products and bread were consumed in moderation. The modern Cretan diet still incorporates many traditional foods but has seen an increase in foods like fast food, soft drinks, and a decrease in cereal consumption from the traditional diet. While longevity in Crete remains high compared to other regions, chronic disease risks are rising with the dietary shifts away from the original Mediterranean diet.