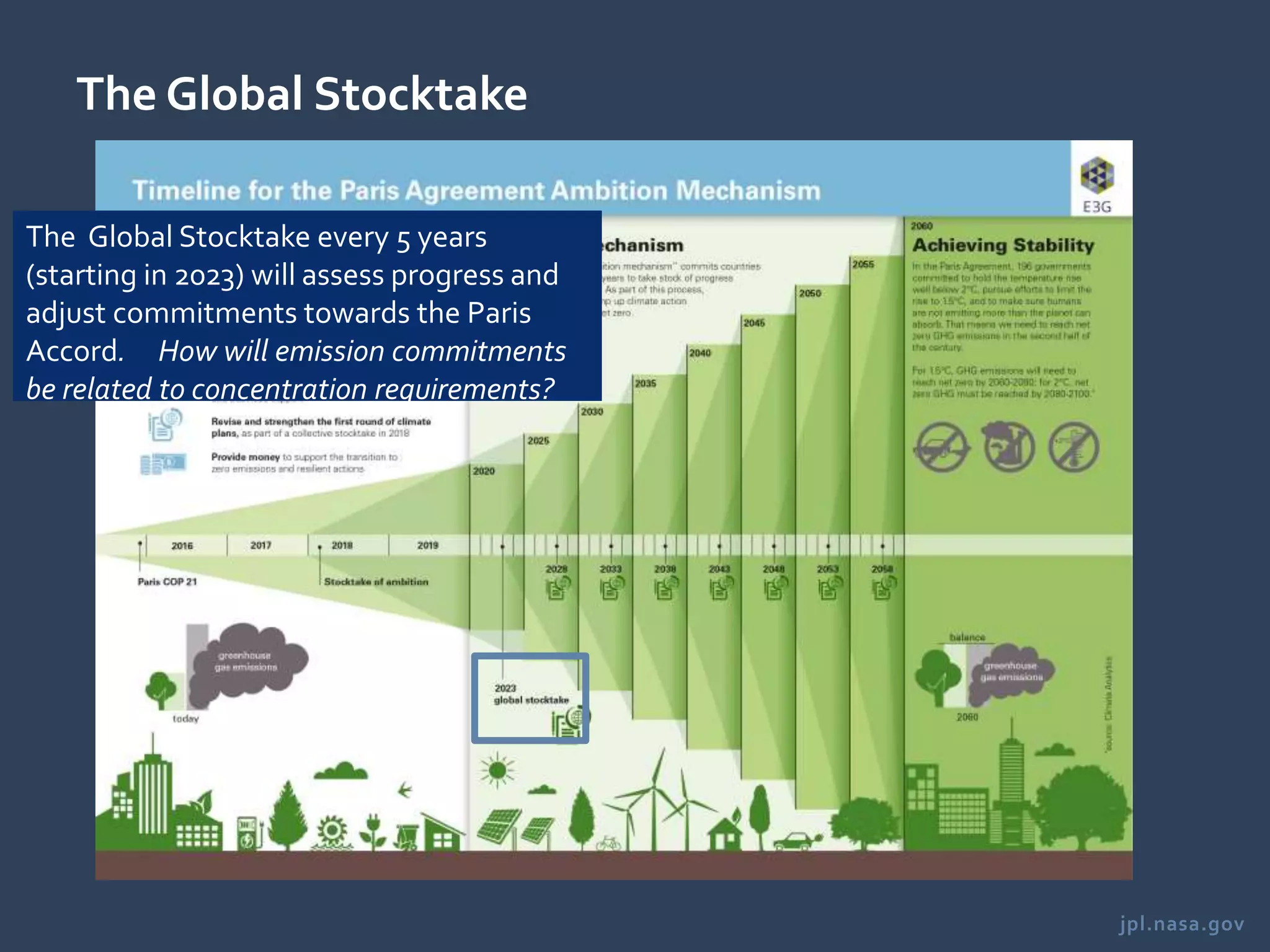

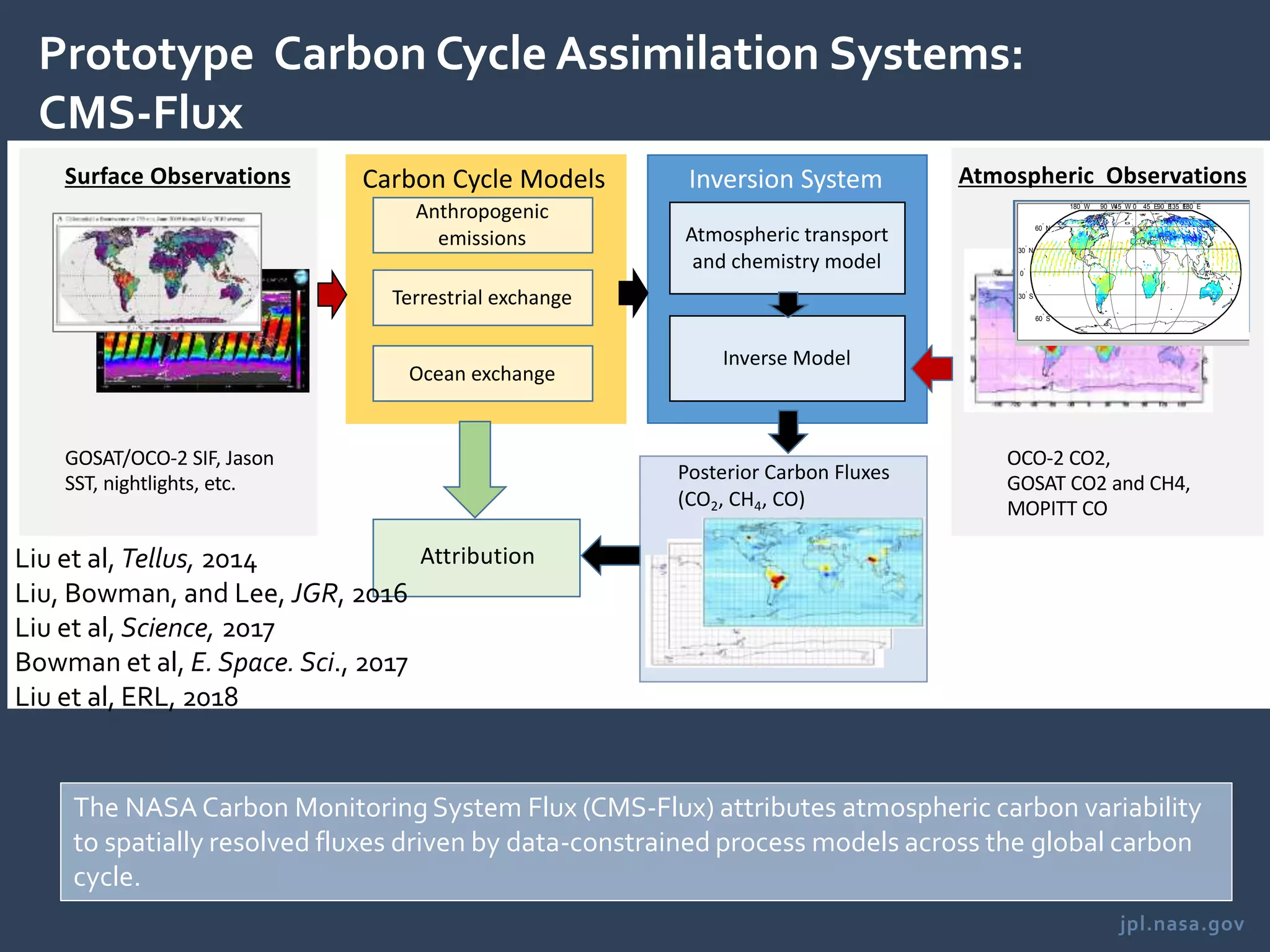

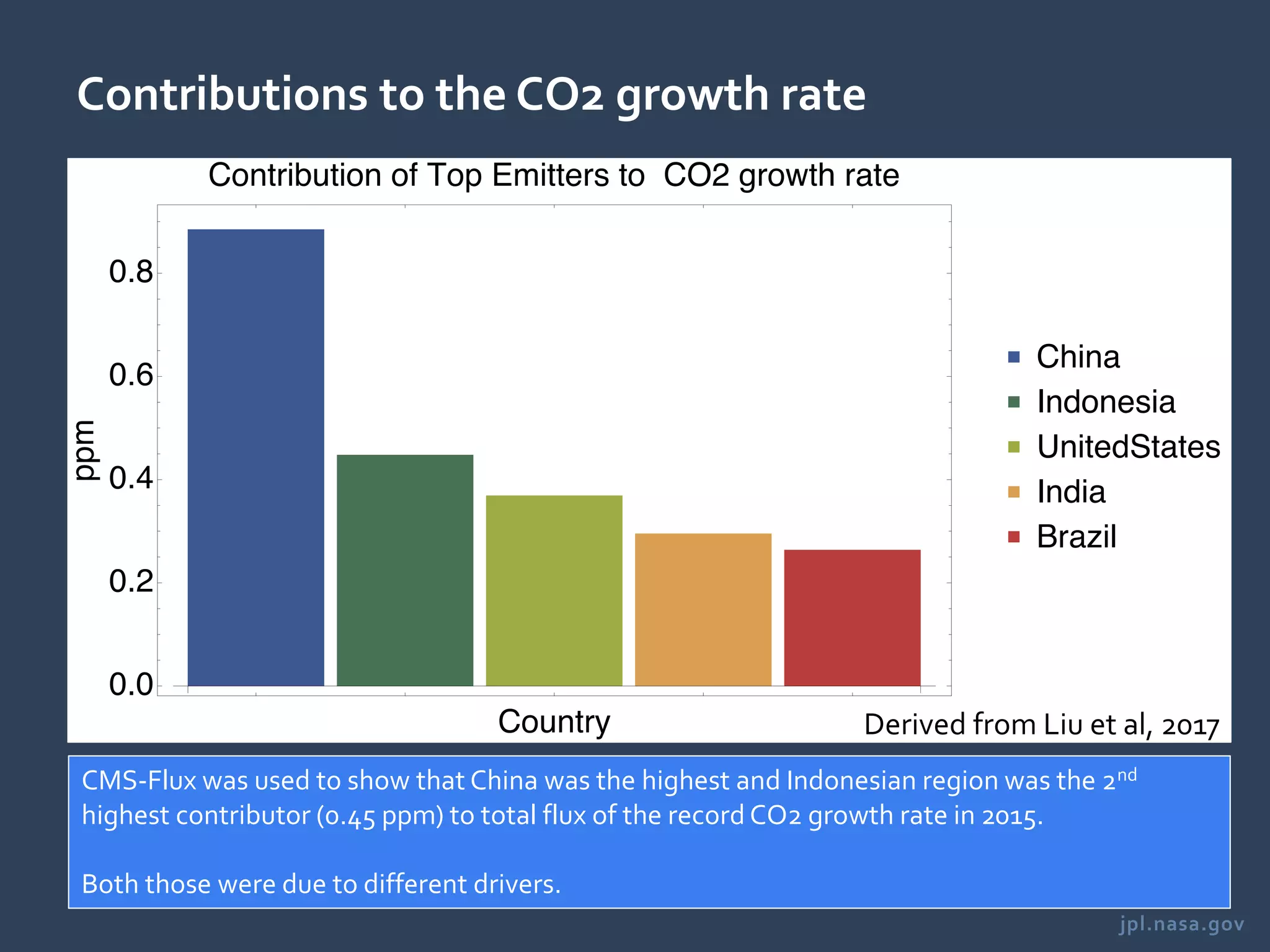

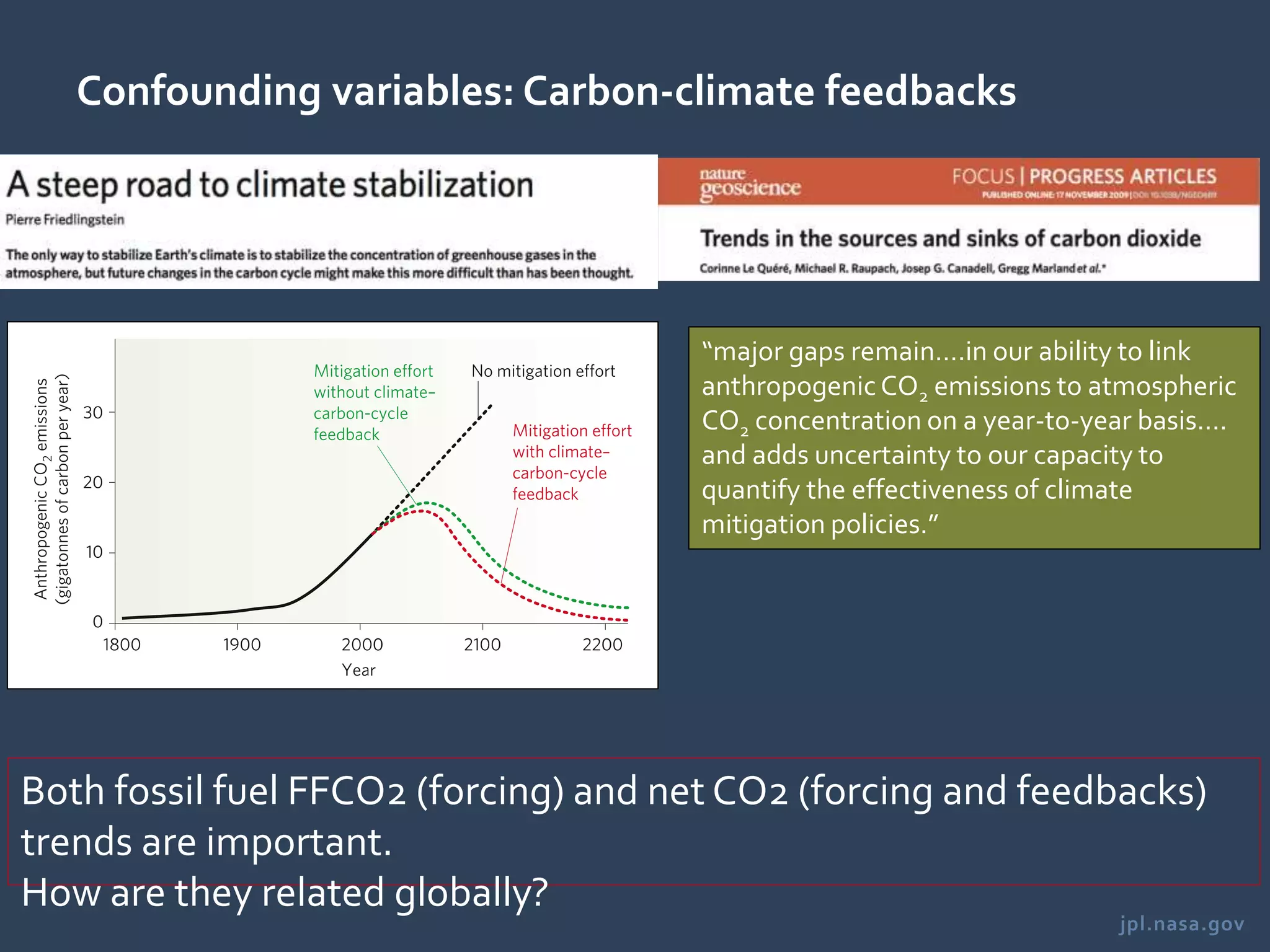

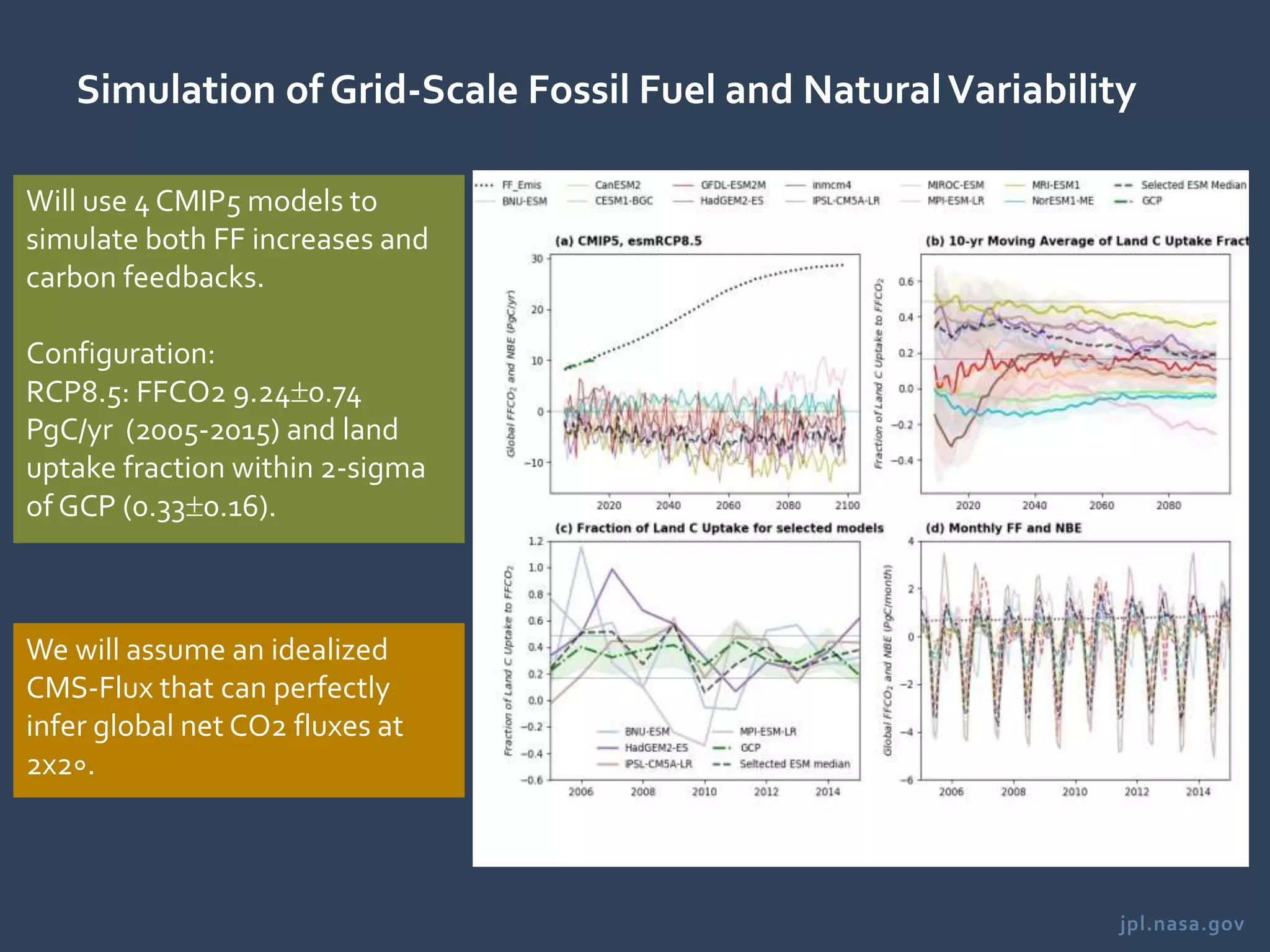

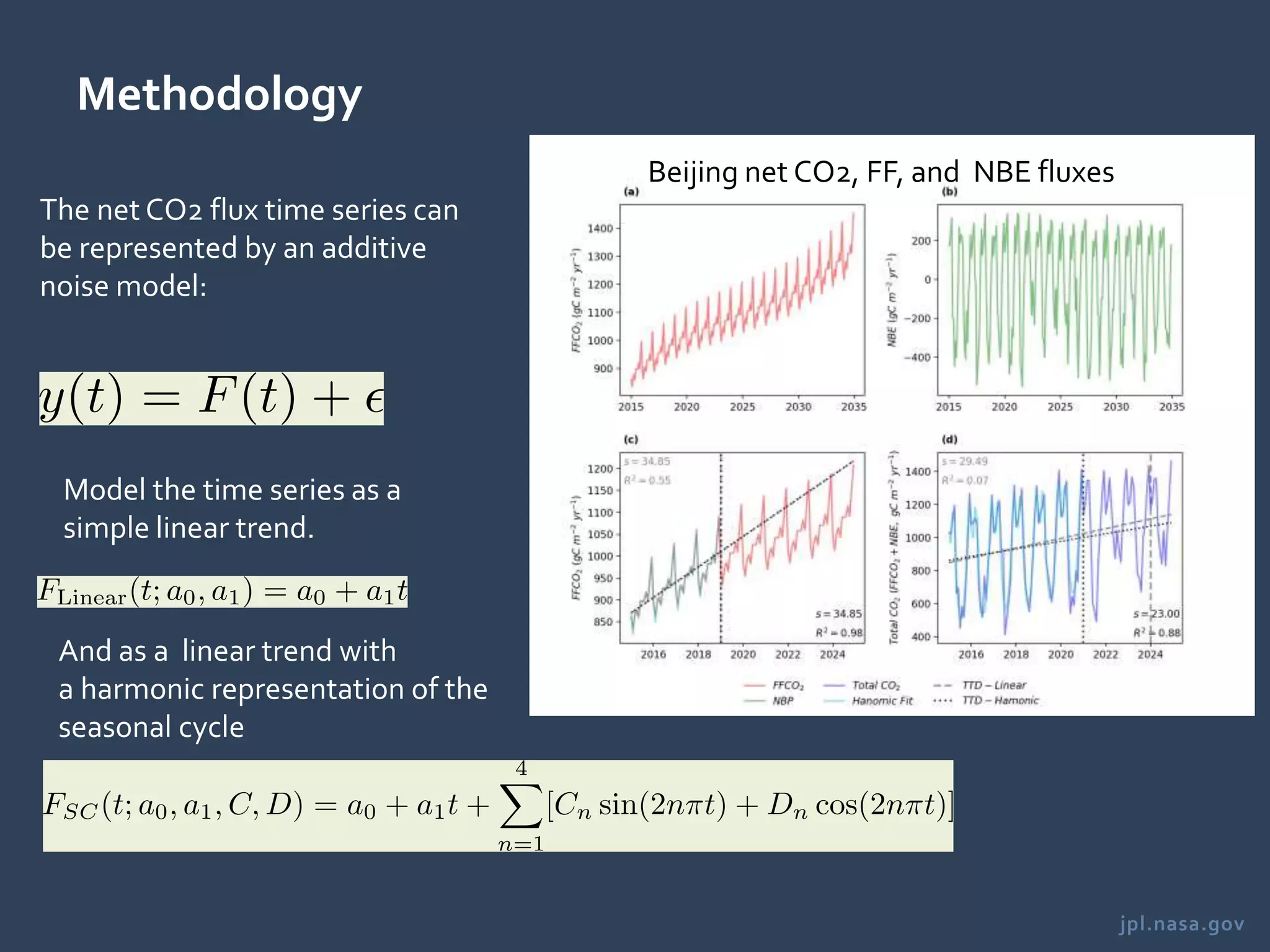

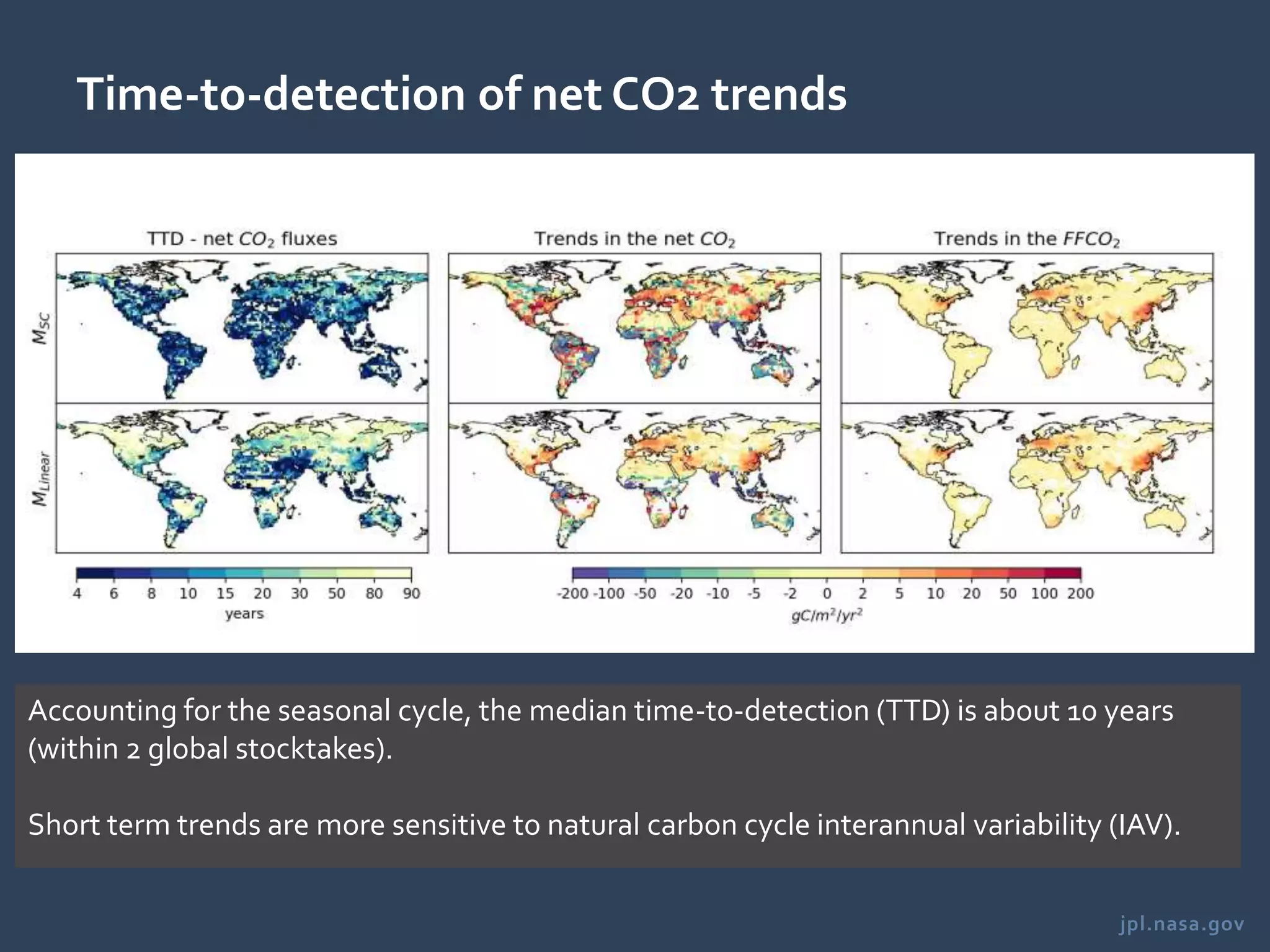

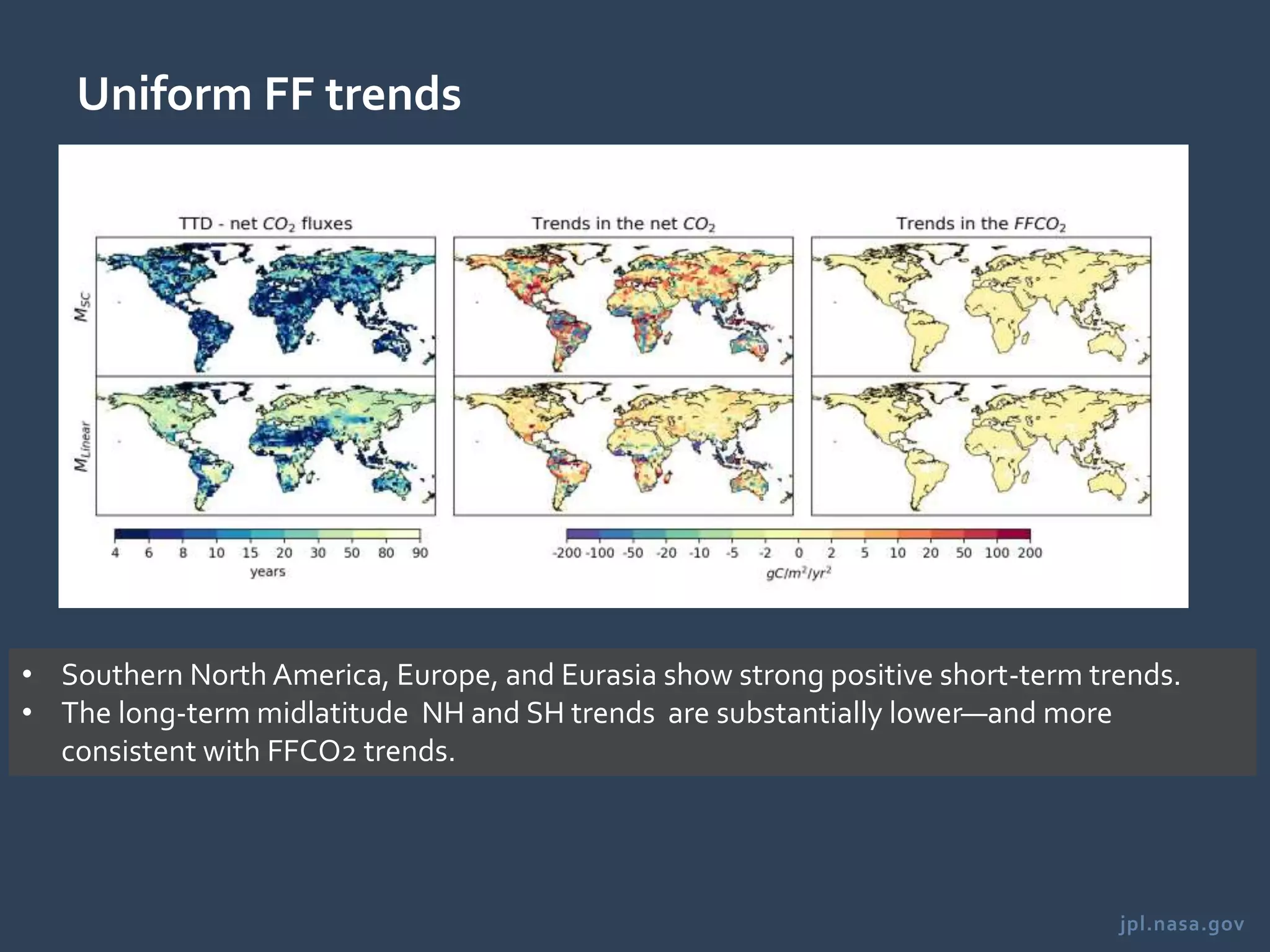

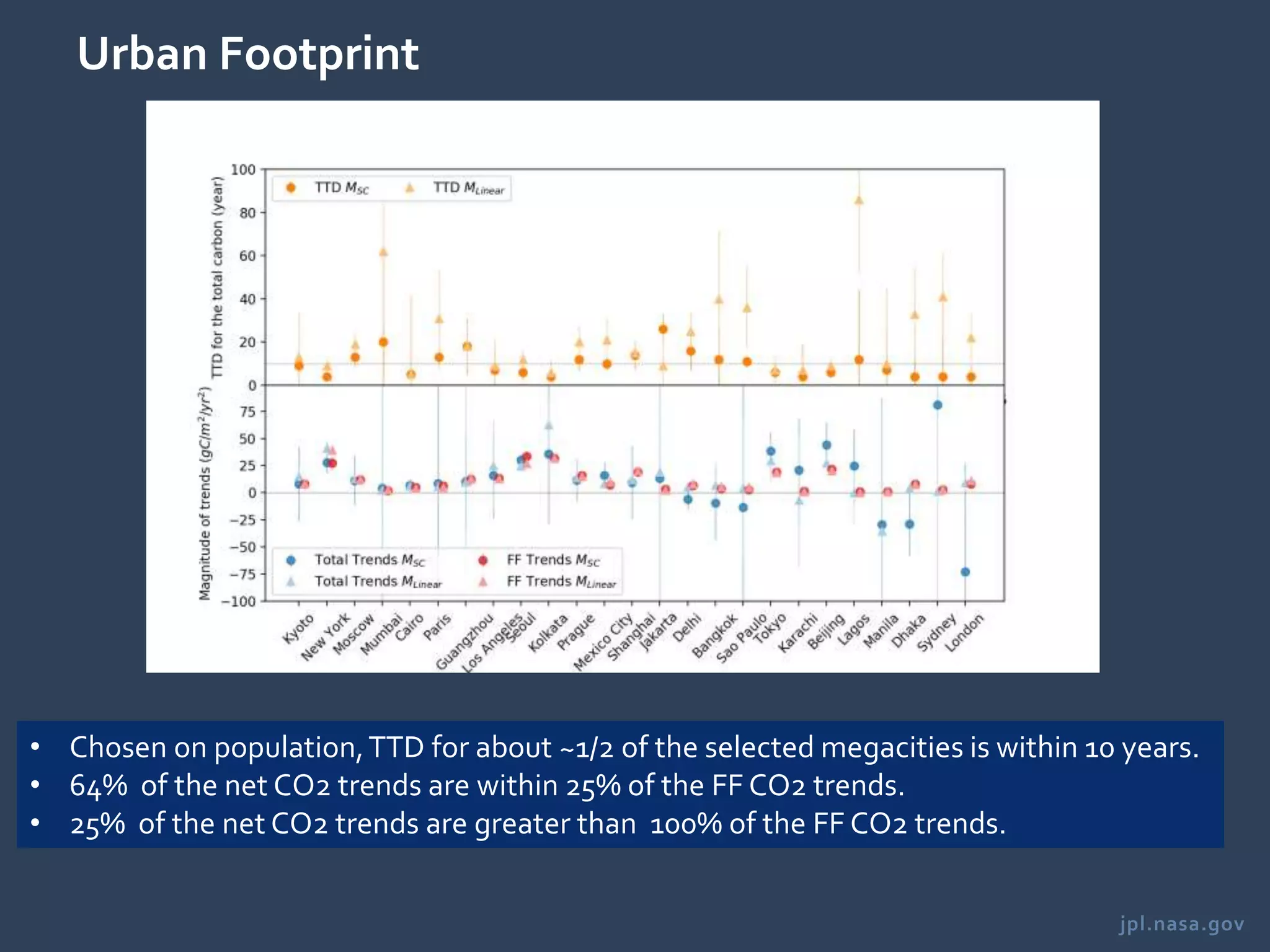

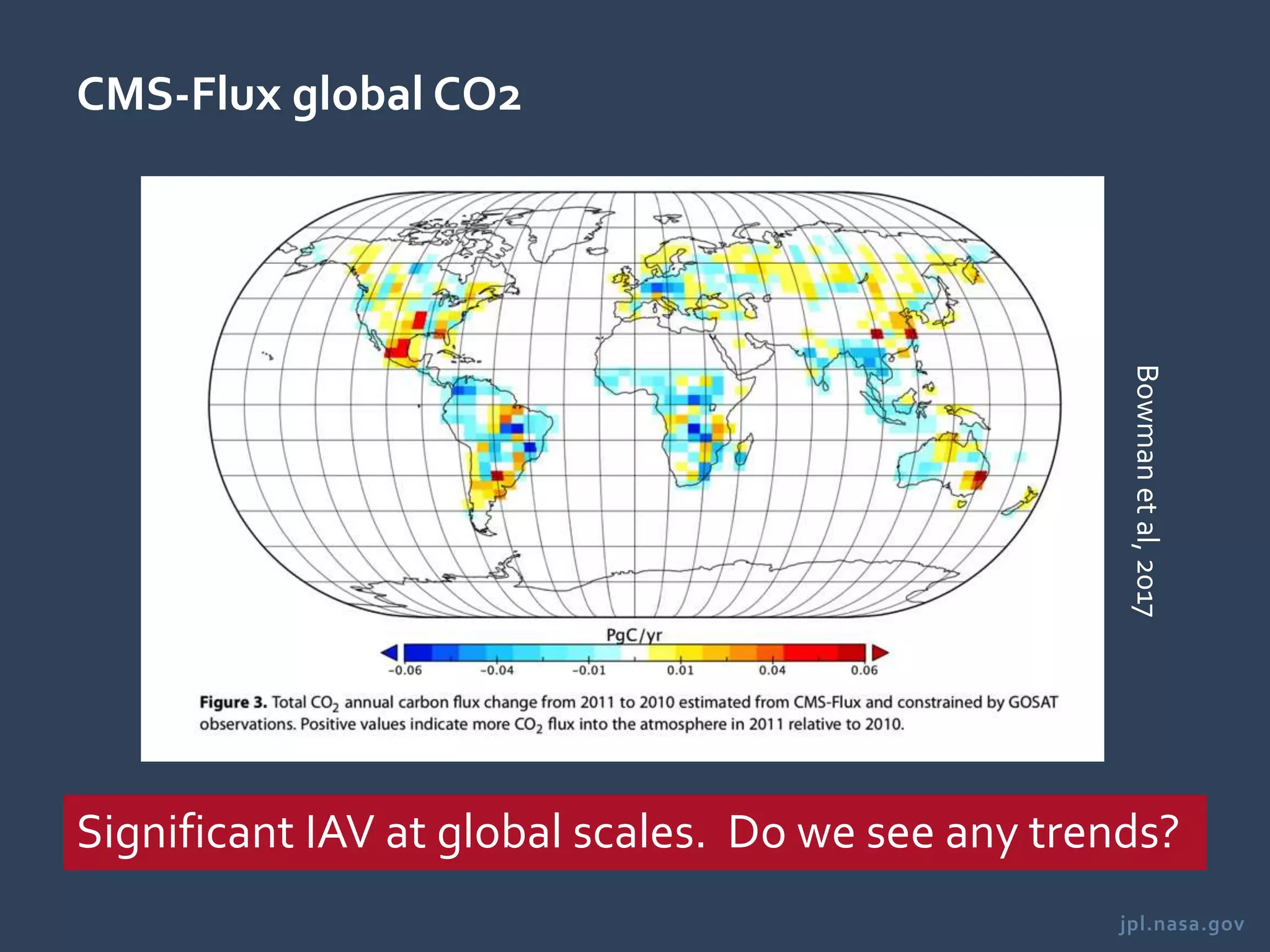

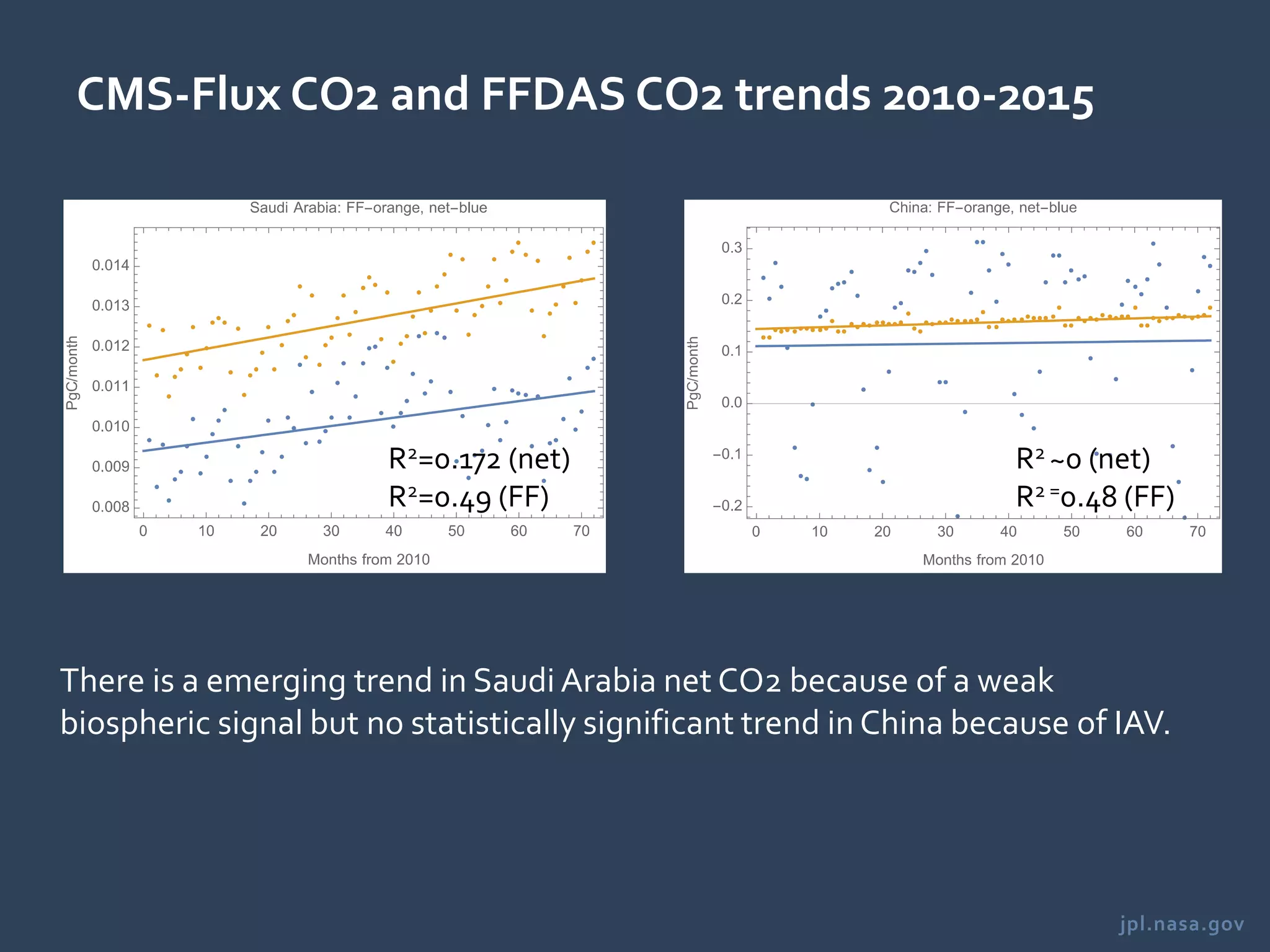

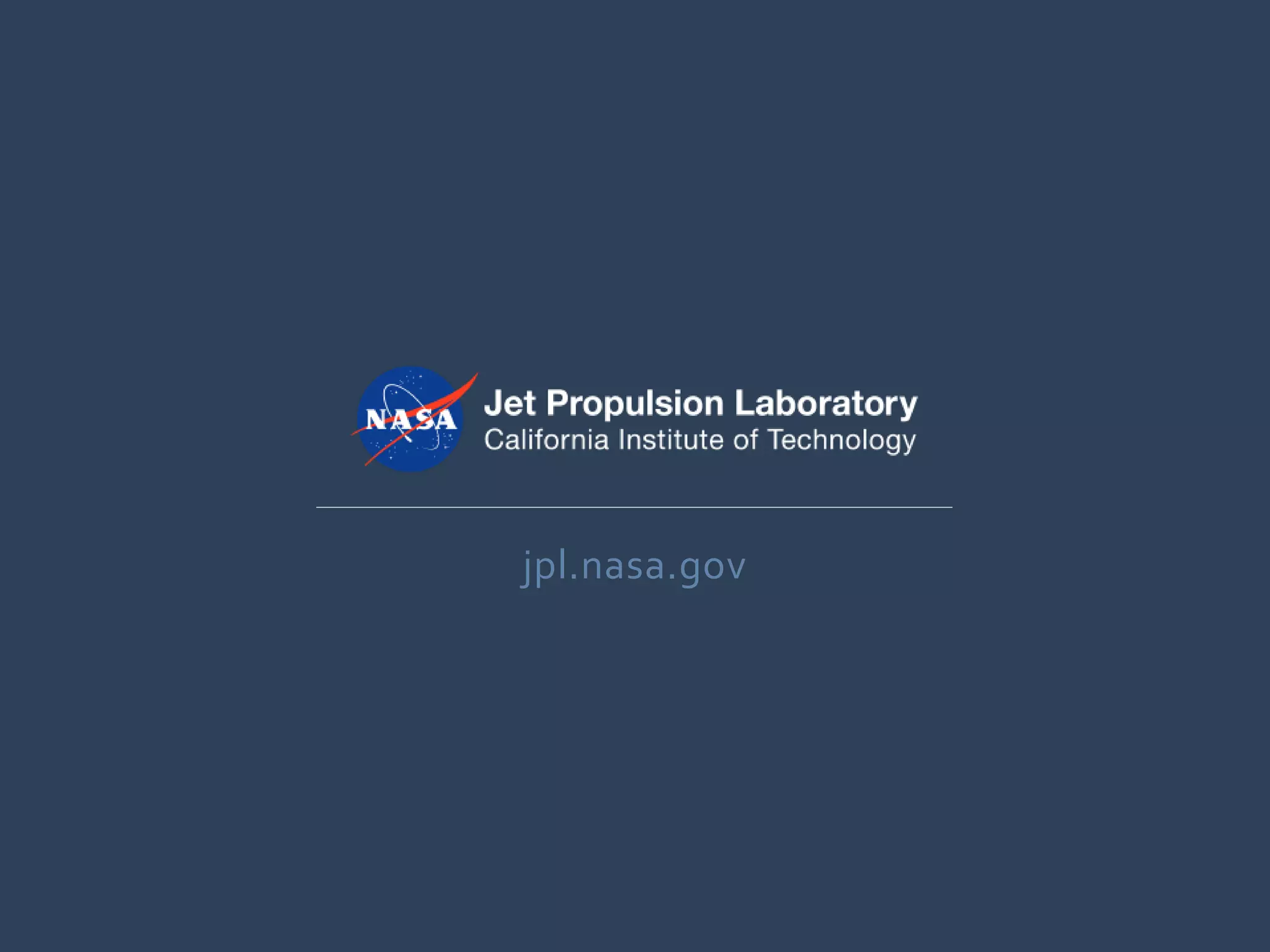

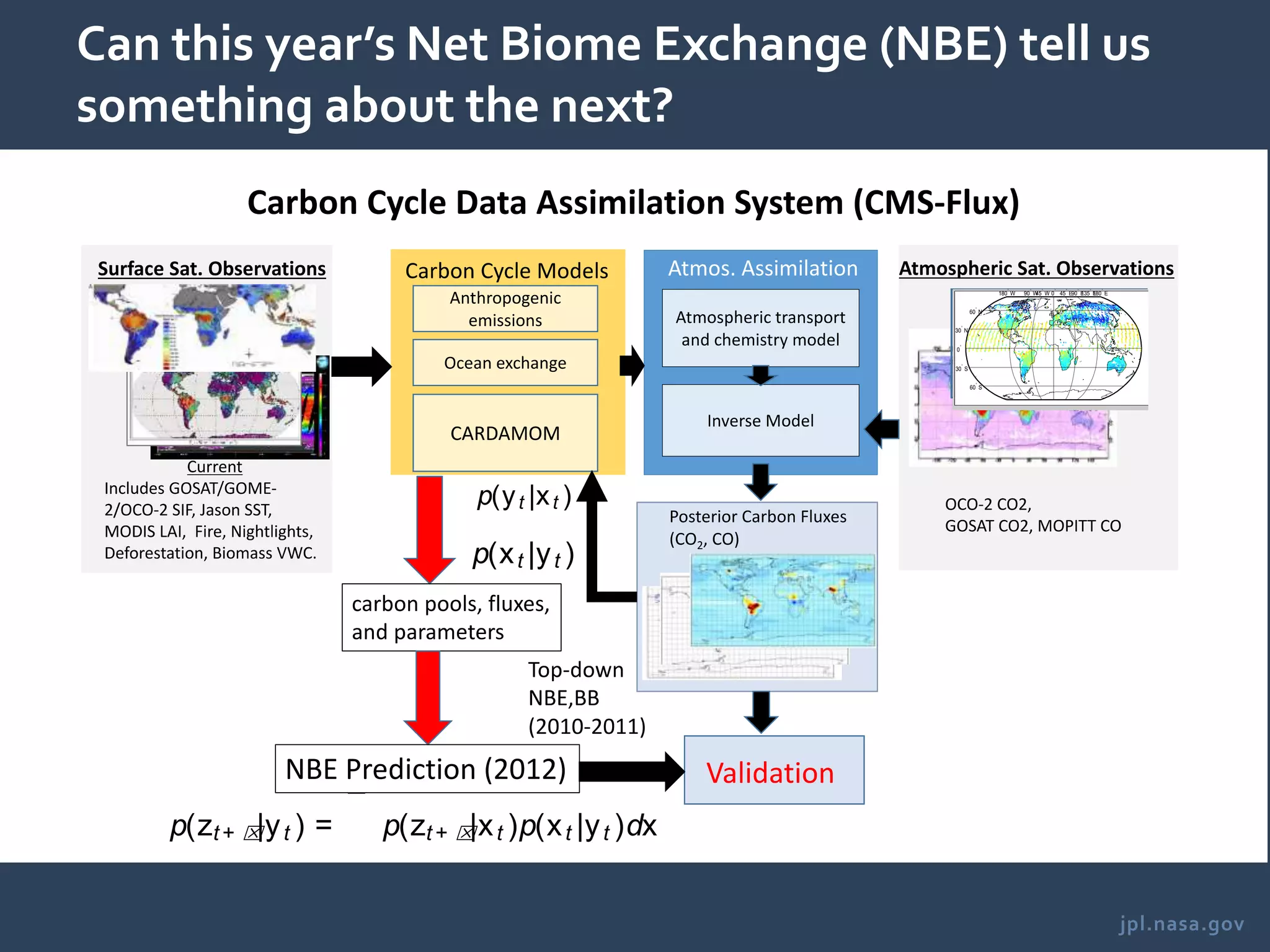

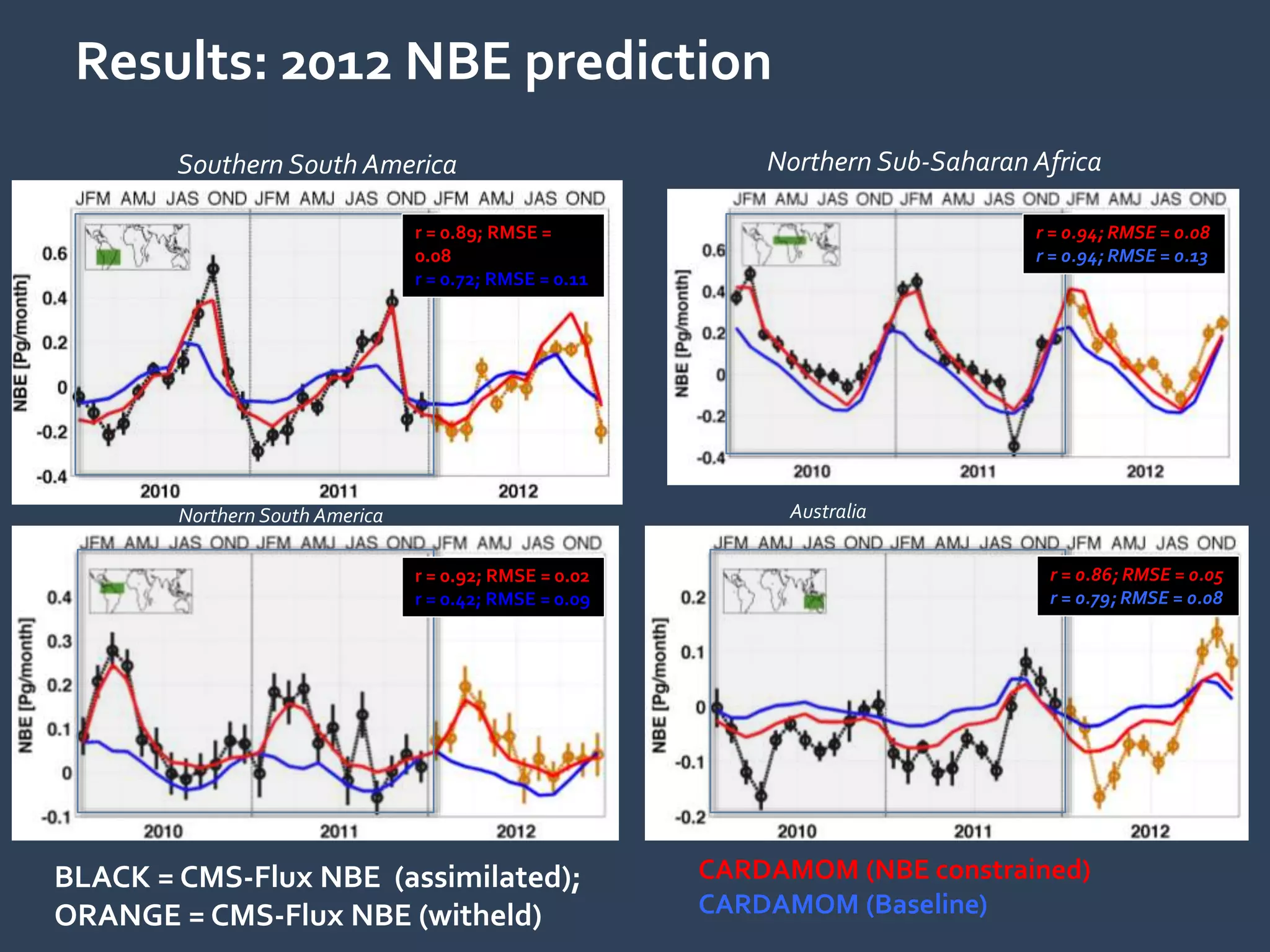

This document discusses using data from satellite instruments and carbon cycle models to attribute trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide to specific regions and sources. It describes the NASA Carbon Monitoring System Flux (CMS-Flux) model which uses data from satellites like OCO-2 and GOSAT to constrain process models and attribute variability in the global carbon cycle to spatially resolved surface fluxes. The document examines using CMS-Flux to detect trends in net CO2 fluxes from different regions within 10 years or between two global stocktakes, though natural variability introduces uncertainty. It also explores using multiple climate models to simulate the effects of fossil fuel emissions and natural carbon cycle feedbacks on regional net CO2 trends.