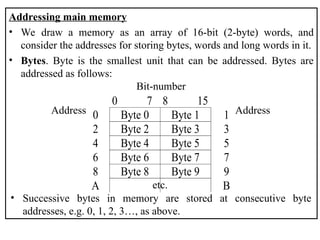

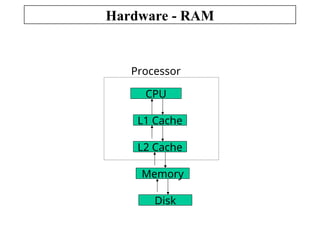

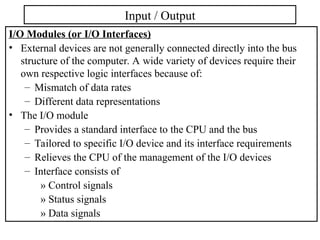

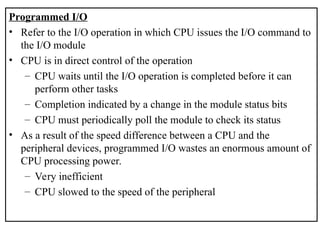

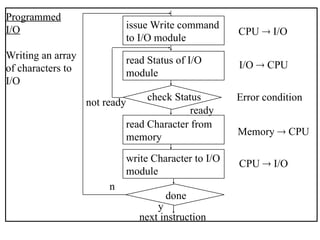

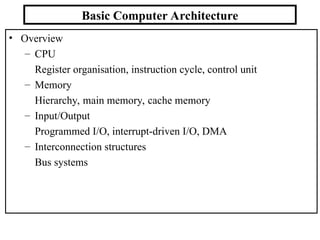

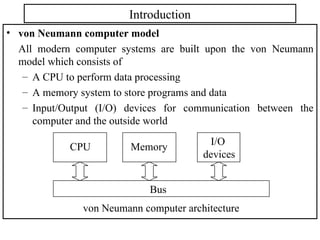

The document outlines the fundamentals of computer architecture, focusing on the CPU, memory hierarchy, and input/output systems. It explains the von Neumann model, organization of the CPU, instruction cycle, various types of registers, and differences between programmed, interrupt-driven, and direct memory access I/O. It also discusses the complexities of cache memory and the implications of hardware vs. microprogrammed control in CPUs.

![Register transfer language (RTL)

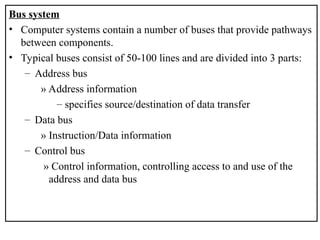

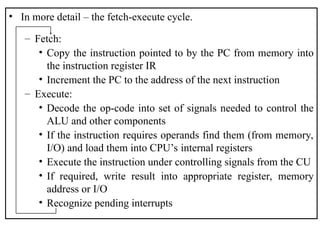

• To describe the details of operation of the CPU, we use a simple

language called RTL. The notations are as follows:

– Reg denotes contents of register Reg; Reg may be, for example,

MAR, MBR, PC, IR, D0, A5, ….

– Mem[x] denotes contents of a memory cell with address x;

sometimes [x].

– Mem[Reg] denotes contents of a memory cell whose address is

given by the contents of register Reg; sometimes [Reg].

– We use to denote transfer of contents: MAR PC means that

the contents of PC are transferred into MAR; PC Mem[x]

means that the contents of address x are transferred into PC; and,

Mem[x] PC means that the contents of PC are stored in

memory address x.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session11c-250124070911-38df02c9/85/Data-path-of-Computer-Architecture-ALU-and-other-components-13-320.jpg)

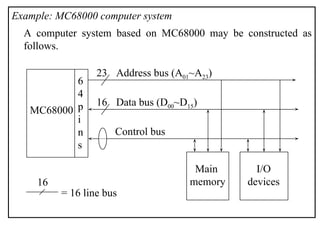

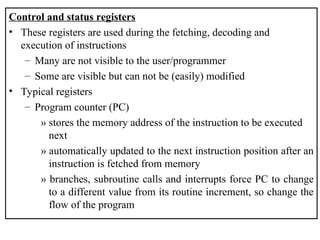

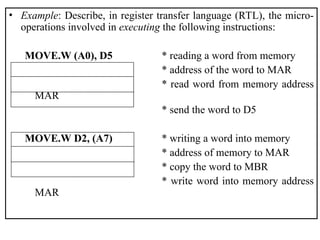

![• Example: In RTL, the fetch-execute cycle for the instruction

ADD.W ($2000), D0 (in MC68000 assembly

language)

i.e. add the contents of memory address $2000 to the contents of a

data register D0 and store the result in D0 – can be expressed as

(assume that each instruction is 16 bits wide, or 2 bytes wide):

MAR PC move contents of PC to MAR

PC PC + 2 increment PC by 2 (why 2 ?)

MBR Mem[MAR] read instruction from memory

IR MBR move instruction to IR

CU IR(op-code) move op-code to CU

MAR IR(address) operand address ($2000) to MAR

MBR Mem[MAR] read operand from memory

ALU MBR, D0 perform addition

D0 ALU move output of ALU to D0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session11c-250124070911-38df02c9/85/Data-path-of-Computer-Architecture-ALU-and-other-components-14-320.jpg)

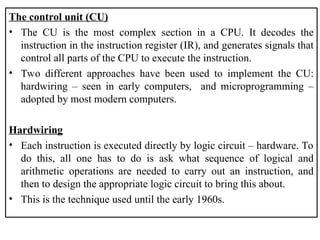

![Microprogramming

• This method was introduced in 1951 by Wilkes.

• Microprogramming means that each instruction could be translated

into a sequence of even more primitive instructions called

microinstructions, which specify the control signals for the

electronic components in every detail.

• For example, the operation ‘fetch an instruction’ in a fetch-execute

cycle can be decomposed into microinstructions as follows

MAR PC move contents of PC to MAR

PC PC + 2 increment PC by 2 (for 16 bit

machine)

MBR Mem[MAR] read instruction from memory

IR MBR move instruction to IR

CU IR(op-code) move op-code to CU](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/session11c-250124070911-38df02c9/85/Data-path-of-Computer-Architecture-ALU-and-other-components-17-320.jpg)