This document outlines key concepts from Chapter 3 of the textbook "International Business: Environments and Operations" including:

- The objectives of the chapter which are to discuss political and legal systems, trends, risks, and issues facing international businesses.

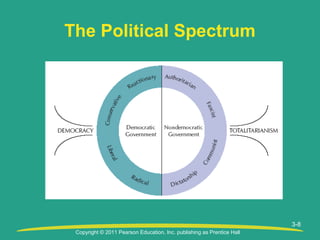

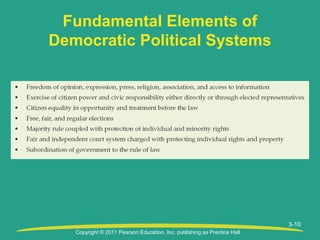

- Definitions of political systems, ideologies, the political spectrum, and types of governments like democracy and totalitarianism.

- Trends in political systems such as the third wave of democracy.

- Definitions of a legal system, the bases of rules, and types of legal systems.

- Operational and strategic concerns that international managers face regarding political and legal environments.