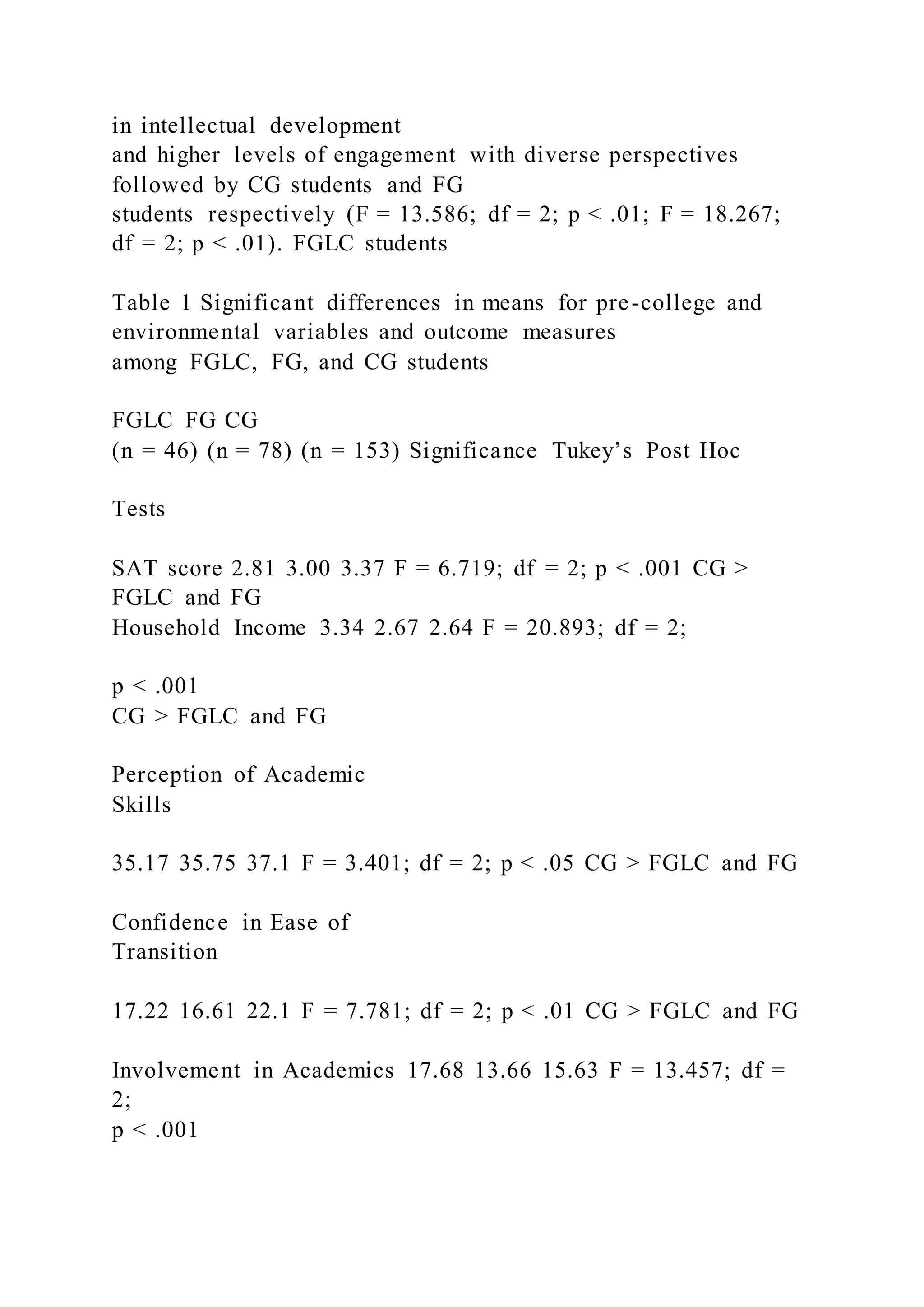

The document outlines a curriculum project for third-grade students at Liberty University, focusing on various educational activities related to character education, ancient Greece, and animal adaptations. It includes a series of lesson plans that integrate writing, math, science, and art with hands-on activities and collaborative group work. Emphasis is placed on developing critical thinking, communication skills, and an understanding of historical content through engaging lessons and multimedia resources.

![unique, but it must clearly explain and perform a representati on

of a direct democracy and a representative democracy. (Multiple

day project)

FINE ARTS

· Dramatic art – Democracy play

· Visual art – Democracy play props

· Visual art – Improper fractions and mixed numbers display.

HEALTH

· The teacher will discuss with the children how predators can

be dangerous to humans and ways students can be aware and

avoid the dangers they present to them.

MOVEMENT / PE

· Acting in the play provides a chance for all students to be

active and to move around.

SAMPLE PLANNING CHARTS

4

ReferencesBlack, I. (2013). Animal adaptations. [Video file].

Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dw7z8Fo5ijkFlocabulary.

(2018). Ancient Greece. [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.flocabulary.com/unit/ancient-greece/

Motivational Archive. (2018 Mar. 9). Watch this everyday-

motivational speech by navy seal admiral

William H. McRaven. [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z7QL6hjeNDA

Rayor, L. (2012). Avoiding predators: How to avoid being

eaten. [Video file]. Retrieved

from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B2JdRPKYyTcSchwartzberg

, M. (n.d). What did democracy mean in Athens? [Video file].

Retrieved from https://ed.ted.com/lessons/what-did-democracy-

really-mean-in-athens-melissa-schwartzberg Scientist Cindy.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-11-2048.jpg)

![(2016). Coolest camouflage – animal adaptations. [Video file].

Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jsTW6xwjLyY

Virginia Department of Education. (2008). History and social

science standards of learning

for Virginia public schools: Grade 3 introduction to history and

social science.

Retrieved from

http://www.doe.virginia.gov/esting/sol/standards_docs/

history_socialscience/next_version/stdshistory3.pdf

Virginia Department of Education. (2010). English standards of

learning curriculum

framework. Retrieved from

http://www.doe.virginia.gov/testing/sol/frameworks/

english_framewks/2010/framework_english_k-5.pdf

Virginia Department of Education. (2010). Grade three science

standard of learning for Virginia public schools-

2010. Retrieved from

http://www.doe.virginia.gov/testing/sol/standards_docs/science/

2010/k-

6/stds_science3.pdf

Virginia Department of Education. (2013). Music standards of

learning for Virginia public schools.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-12-2048.jpg)

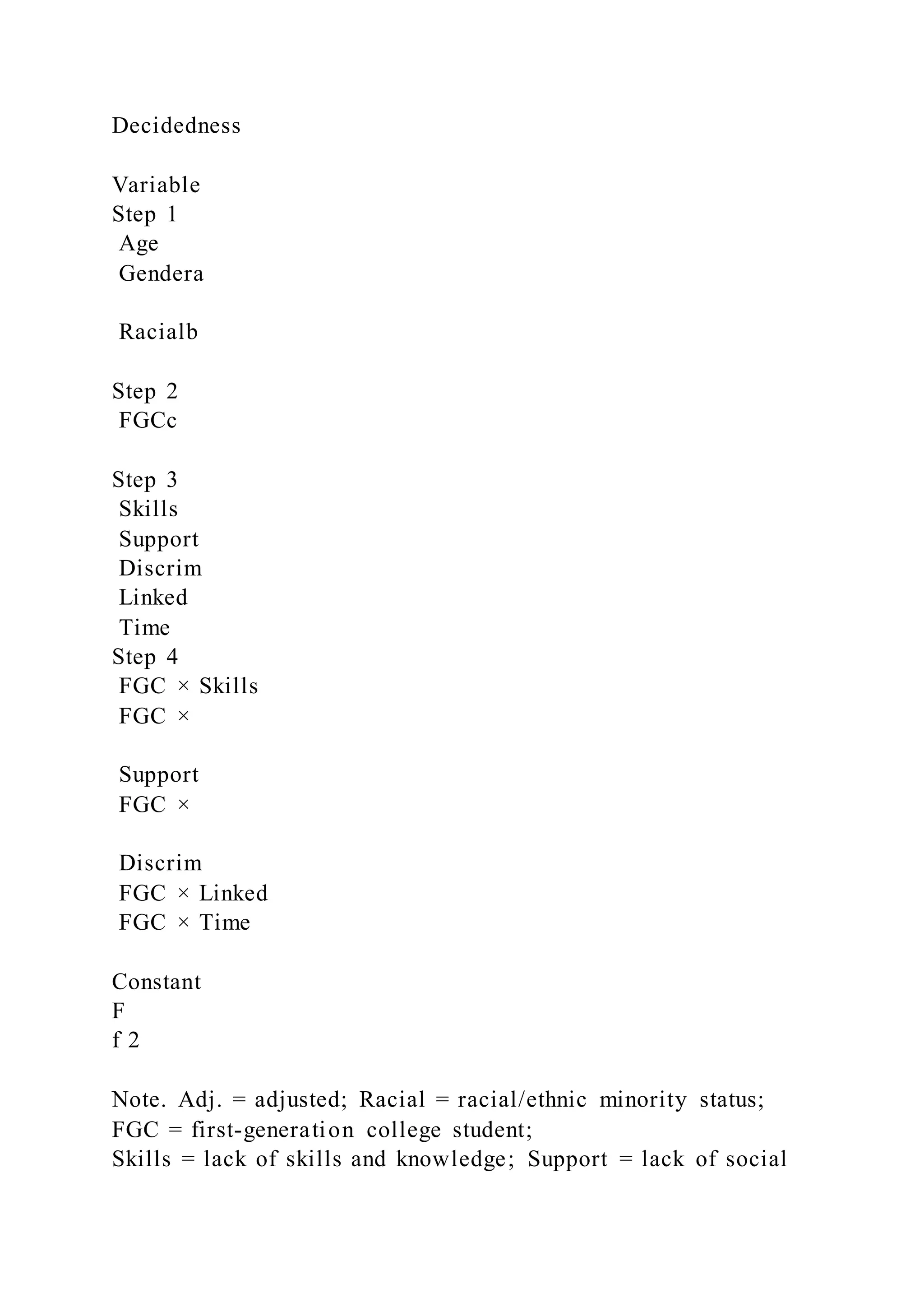

![4,000 undergraduate students who attended 4-year colleges and

univer-

sities in 1991–1994 revealed that, after being admitted to

universities

and colleges, 51% of FGC students cannot complete their

postsecondary

education within 4 years compared with 26% of undergraduate

students

with at least one parent with a bachelor’s degree (Ishitani,

2006).

Teru Toyokawa, Department of Human Development, California

State University

San Marcos; Chelsie DeWald, Department of Psychology,

Pacific Lutheran Univer-

sity. Correspondence concerning this article should be

addressed to Teru Toyokawa,

Department of Human Development, California State University

San Marcos,

333 South Twin Oaks Valley Road, San Marcos, CA 92096

(email: [email protected]

csusm.edu).

The Career DevelopmenT QuarTerly DECEMBER 2020 •

VOLUME 68 333

Even if they can complete their education, FGC students

experience

disadvantages in transitioning from school to work because of

challenges

and barriers to their career exploration and planning (Olson,

2014).

Although FGC students’ academic challenges during education

have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-16-2048.jpg)

![Konstam, V., & Lehmann, I. S. (2011). Emerging adults at work

and at play: Leisure,

work engagement, and career indecision. Journal of Career

Assessment, 19(2), 151–164.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072710385546

Lauff, E., & Ingels, S. J. (2013). Education Longitudinal Study

of 2002 (ELS:2002): A first

look at 2002 high school sophomores 10 years later (NCES

2014-363). National Center

for Education Statistics.

https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014363.pdf

Lee, S. H., Yu, K., & Lee, S. M. (2008). A typology of career

barriers. Asia Pacific Educa-

tion Review, 9(2), 157–167.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03026496

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a

unifying social cognitive

theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance

[Monograph]. Journal

of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122.

https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027

Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (2000). Contextual

supports and barriers to

career choice: A social cognitive analysis. Journal of

Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 36–49.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.36

Lewis, C., & Keren, G. (1977). You can’t have your cake and

eat it too: Some consid-

erations of the error term. Psychological Bulletin, 84(6), 1150–

1154. https://doi.

org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.6.1150](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-75-2048.jpg)

![When students go to college, they grow and become mature

individuals, expand their

knowledge academically and socially, and gain a better

understanding of different careers,

1El Camino College, Torrance, CA, USA

Corresponding Author:

Rosean Moreno, El Camino College, 18232 Index St., Porter

Ranch, CA 91326, USA.

Email: [email protected]

849756 JHHXXX10.1177/1538192719849756Journal of

Hispanic Higher EducationMoreno

research-article2019

https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/journals-permissions

https://journals.sagepub.com/home/jhh

mailto:[email protected]

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1177%2F15381927

19849756&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2019-05-18

214 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 20(2)

including which one is right for them (Pascarella & Terenzini,

2005). Students choose to

go to college because a college degree increases their income by

almost 50% compared

with someone who only has a high school diploma (Swail, Redd,

& Perna, 2003).

First-generation college students in particular are a growing

population in U.S. col-

leges. Between 1980 and 2011, first-generation college students

increased 73%, mak-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-83-2048.jpg)

![supportive. Always

understanding. I would tell my mom like I have to be at the

library until this time working

on this stuff and “echale ganas [give it your all]” that was all I

needed from them.

When the participants went home, it was often a time to tune

out school and take all

the time to spend with their loved ones. The literature described

how parents often

tried to support their children, however did not understand what

they were doing

(Stephens, Hamedani, & Destin, 2014), and the fact that first-

generation college stu-

dents are highly motivated by their families (Irlbeck, Adams,

Akers Ci Burris, &

Jones, 2014), which were concepts also seen in this study. Each

of the participants

stated their parents supported them as much as they could;

however, they did not

222 Journal of Hispanic Higher Education 20(2)

support them academically or financially because they did not

know how or could not

provide the funds. Saenz et al. (2007) described how finances

played a significant role

in the lives and experiences of first-generation college students,

and for this study,

financial difficulty often arose and made college much more

difficult. One individual

talked about being accepted to her dream school for college;

however, that excitement

was short-lived when her parents told her they could not afford](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-102-2048.jpg)

![learning community outperformed continuing-generation

students in gains in intellectual

development, interpersonal development, and engagement with

diverse perspectives.

There was no significant difference in persistence between first-

generation students

who were in the learning community and those who were not.

Keywords First-generation students . Student development .

Student involvement . Learning

communities . Persistence

Innovative Higher Education (2020) 45:285–298

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09502-0

Gail Markle is Associate Professor of Sociology at Kennesaw

State University. She has a B.S. in Business

Administration from East Carolina University, an M.S. in

Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of North

Texas, and a Ph.D. in Sociology from Georgia State University.

Her research interests include nontraditional

students, student loan debt, and persistence. Email:

[email protected]

Danelle Dyckhoff Stelzriede is the Interim Director of First-

Year Writing and Visiting Faculty in English at

California State University, Los Angeles. She earned her B.A.

in English from California State University,

Sacramento; her M.A. in English from Loyola Marymount

University; and her Ph.D. in English with an

emphasis on twentieth Century American Literature and U.S.

Empire Studies at Claremont Graduate University.

Her current research interests include translingual approaches to

teaching first-year writing and high-impact

academic practices for first-year, first-generation college

students. Email: [email protected]

* Gail Markle](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-126-2048.jpg)

![[email protected]

Danelle Dyckhoff Stelzriede

[email protected]

Extended author information available on the last page of the

article

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1007/s10755-020-

09502-0&domain=pdf

mailto:[email protected]

First-generation college students, as a demographic, are

garnering increasing attention in the

general media, academic journals, and institutional reports and

initiatives. According to the

2017 National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) report,

about 30% of U.S. college

students identify as first-generation, which means that neither

parent has attained a college

degree. An extensive body of research has documented common

challenges facing first-

generation students, including lower SAT scores (Atherton,

2014; Penrose, 2002), difficulty

with transition (Choy, 2001; Engle, Bermeo, & O’Brien, 2006),

lower degree completion rates

(Cataldi, Bennett, & Chen, 2018; Engle & Tinto, 2008), higher

student loan debt (NCES,

2017), and lack of support for first-generation students of color

(Phinney & Haas, 2003). As a

result, institutions around the country have begun developing

targeted initiatives for promoting

effective transition, retention, and progress to graduation for

this student population (Ward,

Siegel, & Davenport, 2012).

The sheer number of first-generation college students enrolled](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-127-2048.jpg)

![Education Statistics, 2017). For this study we defined first-

generation students as those for

whom neither parent had obtained a bachelor’s degree and

continuing-generation students as

those for whom at least one parent had obtained a bachelor’s

degree.

Variables and Analysis

Input (pre-college) Variables Perception of academic skills,

confidence in ease of transition,

and predisposition to new perspectives served as pretest

variables. We measured perception of

academic skills using ten Likert-style questions adapted from

Penrose (2002). Students

reported their level of ability (from 1 to 5, with 1 being very

low and 5 being very high) for

such academic skills as communicating ideas in writing and

critically analyzing events,

information, and ideas. Chronbach’s alpha for this measure was

.73. Confidence in ease of

transition represents students’ anticipated level of difficulty in

transitioning to the role of

college student. It is a composite measure consisting of

students’ initial sense of belonging to

the campus community and their anticipation of participating in

college student behaviors. We

measured this variable using five Likert-style questions adapted

from Inkelas and Weisman

(2003). Students reported their level of agreement (from 1 to 5,

with 1 being strongly disagree

and 5 being strongly agree) with statements such as “I feel that

I belong at [name of

university]” and “I am confident about my academic success at

[name of university].”

Chronbach’s alpha for this measure was .72. We measured](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-136-2048.jpg)

![predisposition to new perspectives

using five Likert-style questions also adapted from Inkelas and

Weisman (2003). Students

reported their level of interest (from 1 to 5, with 1 being not at

all interested and 5 being very

interested) in matters such as learning about cultures differ ent

from [your] own and discussing

intellectual topics with friends and other students. Chronbach’s

alpha for this measure was .81.

Other input variables included gender, race/ethnicity, household

income, self-reported SAT

scores, and high school GPA.

Innovative Higher Education (2020) 45:285–298 289

Environmental Variables Environmental variables measured

student involvement in aca-

demics and with faculty, student peers, and campus social

organizations. Students indicated

how frequently in the current semester (from 1 to 5, with 1

being never and 5 being very often)

they had engaged in various activities. We adapted these

measures from Inkelas and Weisman

(2003), Inkelas et al. (2007), Lohfink and Paulsen (2005), Pike

& Kuh (2005), and Soria and

Stebleton (2012). Involvement in academics included five

activities such as brought up ideas

from different courses during class discussion and used critical

thinking skills in class

assignments. Chronbach’s alpha for this measure was .77.

Involvement with faculty included

five activities such as met with a faculty member in his or her

office and visited informally

with a faculty member during a social occasion. Chronbach’s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-137-2048.jpg)

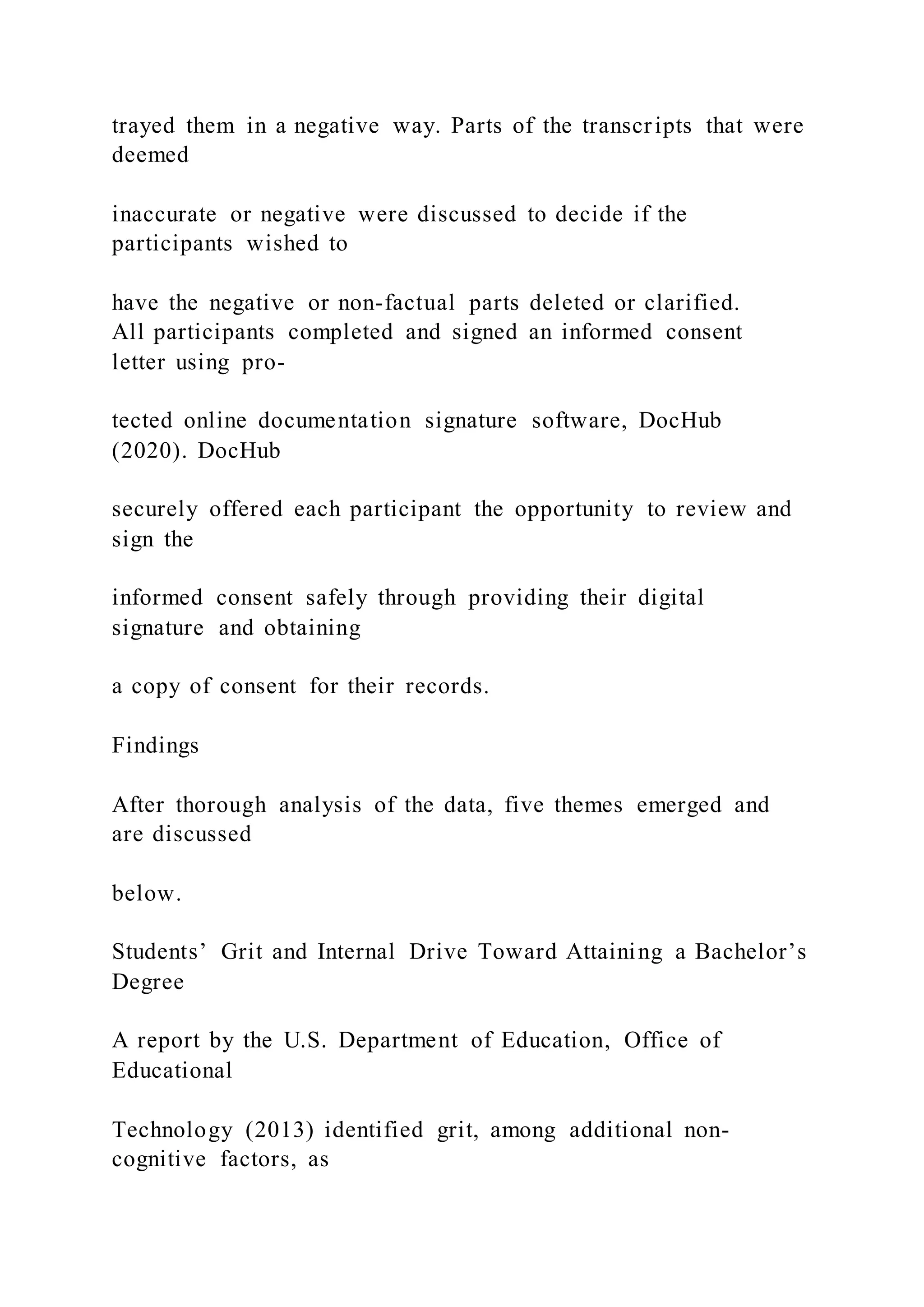

![assist in retention efforts of this population.

1

Department of Counseling and College Student Personnel,

Shippensburg University of Pennsylvania,

Shippensburg, United States

Corresponding Author:

Davina Capik, Department of Counseling and College Student

Personnel, Shippensburg University of

Pennsylvania, 1871 Old Main Drive, Shippensburg, PA 17257,

United States.

Email: [email protected]

Journal of College Student Retention:

Research, Theory & Practice

0(0) 1–25

! The Author(s) 2021

Article reuse guidelines:

sagepub.com/journals-permissions

DOI: 10.1177/15210251211014868

journals.sagepub.com/home/csr

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0253-6813

mailto:[email protected]

http://us.sagepub.com/en-us/journals-permissions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-165-2048.jpg)

![way. When asked about any individuals whom she identifies as

being an influ-

ence on her, like many, CiCi pointed out the professors who she

credits with

helping her persist to her goal of completing an accounting

degree. Cici stated

I very heavily relied on a lot of my professors to answer

questions. I mean, there

were some things that I found out I didn’t find out about my

major until I was

already at [the university] for an accounting major. I relied very

heavily on my

professors to kind of guide me through a lot of things that I had

no experience in.

Meeting with the professors in their department and getting a

feeling, you know,

create relationships with them and get a feeling for what ki nd of

professors they are.

Seeking out and identifying college personnel with whom they

could foster rela-

tionships with was a common sentiment among many students

identified as the first

in their families to pursue college. Many of those interviewed

did not express strong

relationships with staff at their high school when asked about](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-199-2048.jpg)

![wasn’t just a passing whim.

Other participants reported entire support systems encouraging

them to enroll

in their bachelor’s program. This was the experience for Talia,

“My family was

very supportive. My parents, and my house parents at [a

Pennsylvania private

boarding school].” And Fred offered this sentiment regarding

the support he felt

from various members of his family when they learned of the

choice to pursue

higher education, “I live with my mom right now. Big support.

Both my sisters

were very ecstatic when learning I was going back to school.

My mom’s family,

her brothers and sisters, are very supportive.” Family support

proved to be an

indicator of student persistence throughout the study.

Implications and Recommendations

Improving college retention rates among the first-generation

college student

population continues to be a top priority for college student

personnel

(Gallup, 2016; Mitchall & Jaeger, 2018). Amid more first-

generation college

students desire to attain a bachelor’s degree, understanding

factors attributing

to persistence toward their goal and what stakeholders can do to

assist is crucial

for students to remain unwavering toward graduation. Moving

away from def-

icit models previously used (Tierney, 1999; Zervas-Adsitt,

2017), this study cen-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-204-2048.jpg)

![Candela, A. G. (2019). Exploring the function of member

checking. The Qualitative

Report, 24(3), 619–628.

https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=

3726&context=tqr

Chen, X. (2005). First generation students in postsecondary

education: A look at their

college transcripts. Postsecondary education descriptive

analysis report (NCES 2005-

171). U.S. Department of Education, National Center for

Educational Statistics.

https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2005/2005171.pdf

Choy, S. (2001). Students whose parents did not go to college:

Postsecondary access,

persistence, and attainment (NCES 2001-126). National Center

for Education

Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of

Education. https://

nces.ed.gov/pubs2001/2001126.pdf

Cloyd, M. C. (2019). Family achievement guilt as experienced

by first-generation college

students: A phenomenology [Doctoral dissertation].

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/

849d/c271ef4a037c1ccbd975a10a50351854c97c.pdf

Covarrubias, R., & Fryberg, S. (2014). Movin’ on up (to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-220-2048.jpg)

![gov/fulltext/EJ1180306.pdf

Gahagan, J., & Hunter, M. S. (2006). The second-year

experience: Turning attention to

the academy’s middle children. About Campus, 11(3), 17–22.

https://doi.org/10.1002/

abc.168

Gallup, Inc. (2016). Gallup college and university president’s

study. https://news.gallup.

com/reports/194783/gallup-college-university-presidents-study-

2016.aspx

Guetterman, T. C. (2015). Descriptions of sampling practices

within five approaches to

qualitative research in education and the health sciences.

Educational Psychology

Papers and Publications, 263.

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?

article=1275&context=edpsychpapers

Hall, D.L. (2017). Overcoming barriers to college graduation:

The sophomore student

experience with academic integration, retention and persistence

(Publication No.

10690131) [Doctoral dissertation]. Hampton University.

Available from ProQuest

Dissertations and Theses.

Hays, D. G., & Singh, A. A. (2012). A qualitative inquiry in

clinical and educational](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-225-2048.jpg)

![settings. Guilford Press.

Hicks, T. (2003). First-generation and non-first-generation pre-

college students’ expect-

ations and perceptions about attending college. The Journal of

College Orientation and

Transition, 11(1), 1–17.

https://digitalcommons.uncfsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?arti

cle=1009&context=soe_faculty_wp

Hoffman, J. L., & Lowitzi, K. E. (2005). Predicting college

success with high school

grades and test scores: Limitation for minority students. Review

of Higher

Education, 28(4), 455–474.

https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2005.0042

Ishitani, T. (2006). Studying attrition and degree completion

behavior among first-

generation college students in the United States. The Journal of

Higher Education,

77(5), 861–885. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2006.0042

Ishitani, T. (2016). First-generation students persist at four-year

institutions. College &

University, 91(3), 22–34.

Jordan, T. K. (2011). Sophomore programs: Theory, research,

and efficacy [Doctoral

dissertation]. Ohio State University.

https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-226-2048.jpg)

![Schaller, M. A. (2005). Wandering and wondering: Traversing

the uneven terrain of the

second college year. About Campus, 10(3), 17–24.

Sterling, A. J. (2015). Persistence in the sophomore year

following transition from success-

ful first-year program (Publication No. 3730498) [Doctoral

dissertation]. Northeastern

University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Sterling, A. J. (2018). Student experiences in the second year:

Advancing strategies for

success beyond the first year of college. Strategic Enrollment

Management Quarterly,

5, 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/sem3.20113

Stewart, S., Hun Lim, D., & Kim, J. (2018). Factors influencing

college persistence for

first-time students. Journal of Developmental Education, 38(3),

12–20. https://files.eric.

ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1092649.pdf

Thayer, P. B. (2000). Retention of students from first generation

and low-income back-

grounds. Opportunity Outlook. Advance online publication.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/

fulltext/ED446633.pdf

Tibbetts, Y., Harachkiewicz, J. M., Canning, E. A., Boston, J.

S., Priniski, S. J., & Hyde,

J. S. (2016). Affirming independence: Exploring mechanisms

underlying a values affir-

mation: Interventions for first-generation students. Journal of

Personality and Social

Psychology, 110(5), 635–659.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-234-2048.jpg)

![https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/10/04/institutional -

change-required-better-serve-first-generation-students-report-

finds

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/10/04/institutional -

change-required-better-serve-first-generation-students-report-

finds

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/10/04/institutional -

change-required-better-serve-first-generation-students-report-

finds

https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/NASPA-First-generation-

Student-Success-Exec-Summary.pdf

https://firstgen.naspa.org/files/NASPA-First-generation-

Student-Success-Exec-Summary.pdf

Zervas-Adsitt, N. (2017). Stretching the circle: First-generation

college students navigate

their educational journey (Publication No. 10617890) [Doctoral

Dissertation]. Syracuse

University. Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Author Biographies

Davina Capik is a practicing school counselor in Pennsylva nia.

She is a licensed

professional counselor (LPC) in the state of Pennsylvania, a

national certified

counselor (NCC) and national certified school counselor

(NCSC). She received

her Ed.D. in Counselor Education and Supervision from

Shippensburg

University, Masters (M.S.) of Counseling from the University of

Scranton,

Masters (M.Ed.) in Educational Psychology from Edinboro

University and

Bachelors (B.S.) in Applied Psychology from Albright College.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-237-2048.jpg)

![could teach map skills (using longitude and latitude) in Social

Science.[M, SS,] The M stands for Math and the SS stands for

Social Science and you are integrating the two together.

· If you are teaching poetry in English / Language Arts class,

you could introduce your history lesson with a poem such as “O

Captain, My Captain” by Walt Whitman (an homage to Abraham

Lincoln after his assassination following the Civil War.) [LA,

SS,] The LA stands for Language Arts and the SS stands for

Social Science and you are integrati ng the two together.

· If you are teaching the water cycle in Science and a “Rain

Dance” from the Native American culture in SS, you are

integrating 3 subjects. [S, SS, D] The S stands for Science, and

the SS stands for Social Science, and the D stands for Dance.

· If you are teaching how to read and create Historical timelines

in Social Science class, you could have your students create a

timeline using Power Point. [SS, T] The SS stands for Social

Science, and the T stands for Technology.

B. Integration of content and curriculum components. Make sure

to integrate the following content and components:

· Daily integrate reading and writing instruction for English

Language Arts (ELA). Use classic and award-winning

literature. Note what skill you are teaching by using the

literature.

· Daily integrate Fine Arts (Visual Art, Music, Theatre, or

Dance); Health (e.g. You could teach about cell growth in math

class, etc.); and PE (eg. You could teach a dance popular in the

Civil War era.)

· Highlight in yellow (as seen in the example) how you are

frequently providing diverse instruction and accommodations

for exceptional learners.

· Promote critical thinking and use problem solving activities.

· Provide active learning experiences. Plan multiple hands-on

learning experiences and projects. Paper and pencil worksheets

should be used very sparingly.

· Leverage technology. Teachers and students should use

various apps to design and complete projects and reinforce](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/curriculumprojectsampleplanningchartsschool-220921014231-0bc695e0/75/Curriculum-Project-Sample-Planning-ChartsSchool-242-2048.jpg)