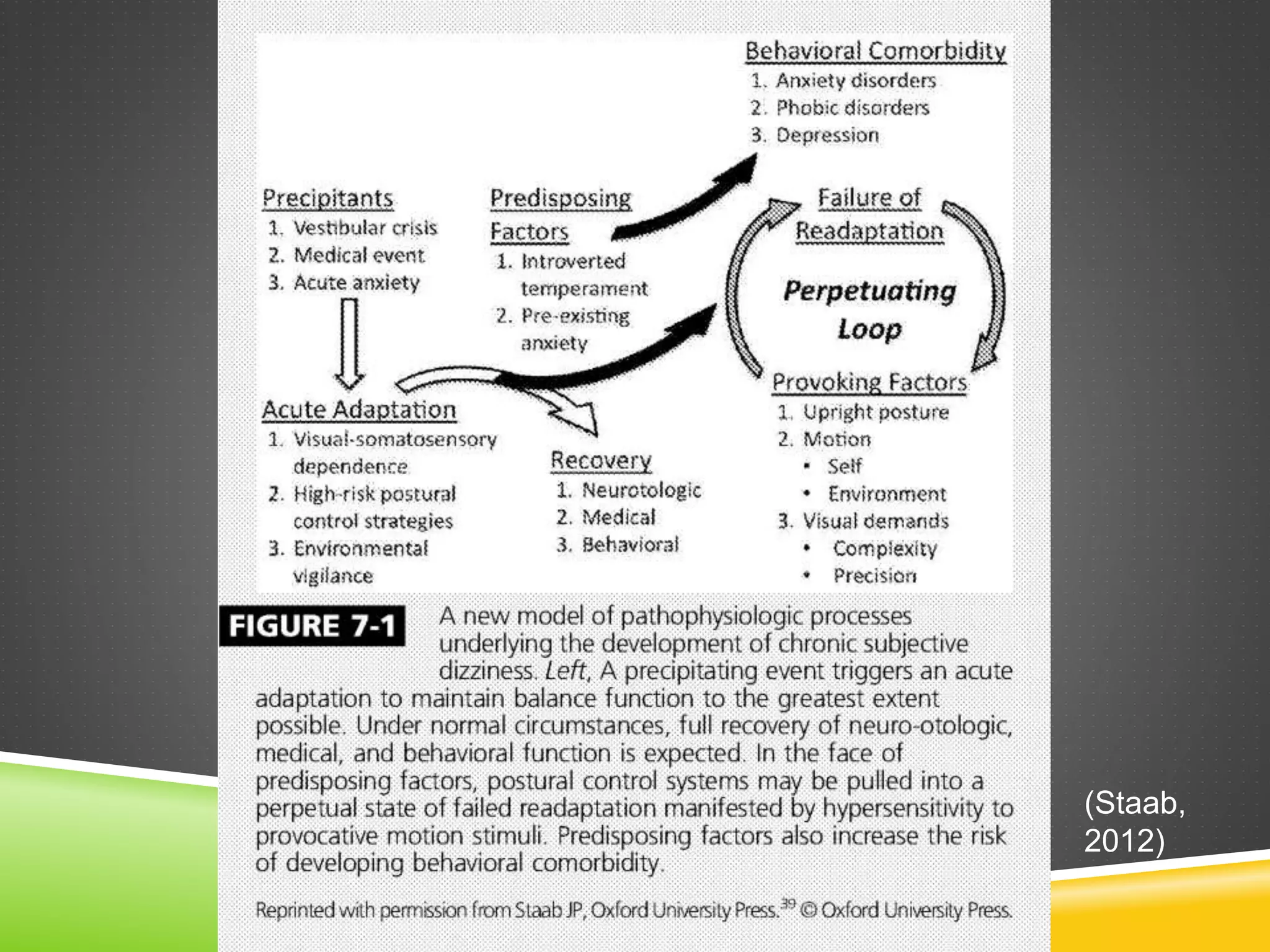

This document discusses chronic subjective dizziness (CSD), a condition characterized by non-vertiginous dizziness or imbalance that is exacerbated by motion and visual stimuli. CSD is thought to develop through classical and operant conditioning following acute vestibular disorders. Treatment involves diagnosis, education, pharmacology like SSRIs, psychotherapy, and vestibular rehabilitation therapy including habituation exercises and graded exposure. CSD is differentiated from other conditions through characteristic symptoms and normal exam findings despite a history of vestibular dysfunction.