This document describes the creation of an "Access for All" training course to teach web developers how to make university websites accessible and compliant with disability legislation. It begins by discussing relevant UK and EU disability laws. It then defines what an accessible website is, examines barriers disabled users face, and considers learning theories. It details the creation of an initial "bad" website to demonstrate accessibility issues, and an improved "good" version following user feedback. The goal is to enable developers to design legal, accessible sites for disabled students.

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

10

2.0 Disability Legislation

This section will outline the disability legislation applicable to the UK as understood

by the author at the time of writing (April 2003) and provides a justification for

developing the AFA project.

The number of students with, and declaring that they have, a disability is equivalent to

the number of students in a large university (see Appendix A). The passing of the

Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001 (SENDA) [1] has conferred upon

these students’ new rights, rights which pervade every area of academic life.

SENDA came into force on September 1st 2002 and introduced the right for disabled

students not to be discriminated against in education, training, and any other services

provided wholly or mainly for students, or those enrolled on courses.

SENDA places educational institutions in the same position as other service

providers; breaches of the SENDA legislation can result in civil proceedings and

potentially high awards against governing bodies.

SENDA requires that educational institutions consider the provision they make for

disabled students and prospective students generally. The duties cover all aspects of

student life including academic activities and wider services such as accommodation

and leisure facilities, examinations and assessments, library and learning resources,

and Web sites.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-11-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

11

2.1 Disability Discrimination Act 1995

The Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) [2] was passed in 1995 to introduce new

measures aimed at ending the discrimination faced by many disabled people.

Education was exempted from the DDA at that time although the exemption was

expected to be removed in 2004. In fact the introduction of SENDA removed the

exemption in 2002.

Part II of the DDA makes discriminatory treatment illegal in relation to employment;

part III of the Act makes discriminatory treatment illegal in relation to access to

goods, facilities and services, and the selling, letting or managing of land or premises.

For employers these measures came into force on December 2nd 1996, for service

providers (e.g. businesses and organisations) the measures were introduced over a

period of time.

Since December 1996 it has been unlawful to treat disabled people less favourably

than other people for a reason related to their disability. Since October 1999 service

providers have had to make reasonable adjustments for disabled people, such as

providing extra help or making changes to the way they provide their services. From

2004 they may have to make reasonable adjustments to the physical features of their

premises to overcome physical barriers to access.

In addition, the DDA requires schools, colleges and universities to provide

information for disabled people and allows the Government to set minimum standards

to assist disabled people to use public transport easily. Many people, both with and

without disabilities, are affected by the Act.

The DDA gives new rights to people who have or have had a disability which makes

it difficult for them to carry out normal day-to-day activities. The disability could be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-12-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

16

The duty to make reasonable adjustments is a duty to disabled people generally, not

just particular individuals. This ‘anticipatory’ aspect effectively means that providers

must consider what sort of adjustments may be necessary for disabled people in the

future and, where appropriate, make adjustments in advance. There is a responsibility

on education providers to find out whether individuals have disability-related needs.

SENDA legislation came into force on 1st September 2002 with two important

exceptions; reasonable adjustments involving the provision of auxiliary aids and

services (such as interpreters etc) come into force on 1st September 2003; the

requirement to make physical adjustments to buildings comes into force on the 1st

September 2005.

2.2.1 DRC Code of Practice

Having established that HE & FE institution Web sites are covered under DDA and

SENDA legislation I will now consider how this works in practice.

The Disability Rights Commission (DRC) [3] is an independent body, established by

Act of Parliament to eliminate discrimination against disabled people and promote

equality of opportunity.

On 26 February 2002, the DRC published a new, revised Code of Practice on the

rights of access to goods, facilities, services and premises for disabled people.[4] This

statutory Code, agreed by Parliament, provides detailed advice on the way the law

should work. It also provides practical examples and tips.

‘The Code's primary function is to provide guidance for both service

providers and disabled people and whilst not an authoritative statement of

the law, there is a requirement that the court consider any part of the Code

which seems relevant.’ [5]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-17-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

17

The May 2002 Guidelines for UK Government Web sites [6] refers to the Code four

times.

With regard to providing services Paragraph 2.14 of the Code lists numerous services

which are covered. In paragraph 2.17 a Web related example is given, clearly

establishing that Web sites are classed as a service and therefore covered under the

DDA.

‘An airline company provides a flight reservation and booking service to the

public on its Web site. This is a provision of a service and is subject to the

Act.’

Accessible Web sites are clearly stated as examples of reasonable adjustments in

Paragraph 5.23, provision for people with a hearing disability, and paragraph 5.26,

provision for people with a visual impairment.

2.3 Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act came into force on 2nd

October 2000 [7], bringing some of the

European Convention on Human Rights into UK law. The rights are binding on public

bodies.

Article 2 of the First Protocol of the Convention provides a right ‘not to be denied

access to education’. European case law has defined the right to education as

including a right to the ‘full benefit of that education’.

Article 14 of the Convention provides a right not to be discriminated against in the

enjoyment of Convention rights on 'any ground such as sex, race, colour, language,

religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a

national minority, property, birth or ‘other status'.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-18-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

18

Disability is not specifically mentioned but is probably covered by the phrase 'other

status'.

2.4 European Union Law

The European Union (EU) recently passed EU Law Parliament Resolution

(2002)0325 regarding the Accessibility of Public Web Sites. This was adopted on

13th June 2002. [8]

In note 31 of the resolution the EU has stressed that, for Web sites to be accessible, it

is essential that they are ‘WCAG AA’ compliant. In other words priority 2 of the Web

Accessibility Initiative (WAI) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

guidelines must be fully implemented. A full discussion of the WCAG guidelines can

be found in Section #.#.

EU legislation is legally binding on UK courts and therefore should be taken as the

legal definition of Web Accessibility.

2.5 Sydney Olympic Games Legal Case

At the time of writing there have been very few legal cases relating to accessible Web

sites. The majority of potential cases tend to be settled out of court because the

defendants wish to avoid negative publicity. AOL, Barnes & Noble, and Claire’s

Stores [9] have already settled potential cases out of court without admitting liability.

The University of Kentucky has a list of University related disability legal cases, [10]

most of which have ended with the Universities agreeing to put things right –

‘voluntary resolution’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-19-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

19

There has been one key legal action which was brought under the Commonwealth

Disability Discrimination Act 1992, namely Bruce Lindsay Maguire v Sydney

Organising Committee for the Olympic Games (SOCOG) [11]

This case is not legally binding on UK courts but it is likely to be regarded as highly

persuasive. It is common for the UK courts to consider cases in other courts when

dealing with ‘new technology’ issues.

Bruce Maguire was born blind and uses a refreshable Braille display. He complained

that the Sydney Olympic Games Web site was not accessible to him as a blind person.

In particular, alternative text was not provided on all of the site images and

imagemaps. Furthermore Maguire could not access the Index of Sports or the Results

Tables.

The Human Rights & Equal Opportunities Commission (HREOC) delivered a

landmark ruling on 24th

August 2000 when they found that SOCOG were in breach of

Australia's DDA. SOCOG ignored the ruling and were fined A$20,000.

The HREOC dismissed defence arguments presented by SOCOG and IBM (who built

the site). The defendants argued that it would be excessively expensive to retrofit the

site to remove accessibility barriers and (over) estimated retrofit costs to be in the

region of A$2.2 million. This defence was rejected by the HREOC.

SOCOG did not actively cooperate with the HREOC. The defendants withheld site

information from Maguire arguing that ‘it was commercially sensitive’ although this

argument was rejected by the HREOC. Moreover, the defendants did not return

telephone calls or reply to correspondence. They also refused to provide a list of

witnesses as directed by the HREOC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-20-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

20

SOCOG never seriously considered disability issues and attempted to ‘bully’ their

way out of their obligations under the law. This case highlights the fact that

compliance with Web accessibility legislation is not optional. FE and HE institutions

need to consider the implications of this landmark case.

2.6 Legal Summary

Disability legislation regarding Web accessibility has been passed in many countries

around the world [12]. The vast majority of these countries cite ‘WCAG AA’ as the

benchmark in their definition of Web accessibility, the one main exception being the

United States which has provided its’ own guidelines, namely Section 508 of the

Rehabilitation Act of 1973 [13].

A discussion of Section 508 is not relevant because the AFA project is aimed at UK

universities. However, sites which comply with UK legislation would automatically

comply with American legislation; Section 508 criteria is not as rigorous as

elsewhere.

This section has clearly demonstrated that UK FE and HE institutions are legally

bound under SENDA legislation, in effect DDA Part IV, to create accessible Web

sites. The potential consequences for non-compliance can be seen in the Maguire v.

SOCOG legal case. If an organisation as big as SOCOG, in partnership with IBM,

can be prosecuted through the courts, UK universities must face the fact that they are

not above the law.

The aim of the AFA project is to prevent FE and HE institutions from falling foul of

disability legislation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-21-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

21

3.0 What is an Accessible Web Site?

In order to train Web developers to design and create accessible Web sites it would be

useful to define what an accessible Web site actually is. This will provide a number of

useful guidelines and constraints.

There are numerous definitions of Web accessibility including the above mentioned

‘WCAG AA’ legal recommendation. The Open Training and Education Network

(OTEN), the largest provider of distance education and training in Australia with

more than 35 000 students enrolled in 660 fully accredited subjects and modules, [14]

defines an accessible Web site as one in which ‘all users can easily enter and navigate

the site, access all of the information and use all the interactive features provided.’ [15]

(Emphasis mine)

Section 508 of the US Rehabilitation Act 1973 states that a Web site is accessible

when ‘individuals with disabilities can access and use them as effectively as people

who don’t have disabilities’.[16]

The Making Connections Unit (MCU), based in Glasgow Caledonian University,

consider four definitions although they actually recommend number 4. [17] An

Accessible Web site is one that will be: -

1. accessible to everyone

2. accessible to the intended audience - though perhaps not accessible to

other groups

3. accessible to disabled people

4. accessible to machines first, and people second

The definition with perhaps the most authority was written by Chuck Letourneau

[18], the man who co-chaired the working group that developed the W3C's Web

Content Accessibility Guideline Recommendation 1.0 [19], the de facto international](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-22-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

22

standard for the design of accessible Web sites [20], and also co-authored the online

training Curriculum for the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0 [21].

Letourneau describes Web accessibility thus: - ‘anyone using any kind of Web

browsing technology must be able to visit any site and get a full and complete

understanding of the information contained there, as well as have the full and

complete ability to interact with the site.’ [22] (Emphasis mine)

3.1 Definitions

3.1.1 ‘Anyone’

‘Anyone’ means every person regardless of their sex, race, nationality or ability -

from people having the full range of visual, aural, physical and cognitive skills and

abilities to those who are limited in any, or all, of them.

3.1.2 ‘Any Web Browsing Technology’

There are more than 100 different Web browsers, many of which have numerous

versions [23]. This figure includes text-only browsers such as Lynx [24], speech

browsers such as the IBM Homepage Reader [25] and the Cast E-Reader [26], as well as

the more popular browsers such as Internet Explorer [27], Netscape [28] and Opera [29].

Web pages can also be viewed by various other devices including screen readers such

as Dolphin Supernova [30], Personal Digital Assistants (PDA’s), Java and WAP

(Wireless Application Protocol) phones, Web and interactive TV and there is even an

Internet fridge [31]. An excellent source of information on dozens of accessibility

related products is the TECHDIS Accessibility Database [32].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-23-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

23

To comply with our accessible Web site definition, pages should be viewable on all of

these devices.

3.1.3 ‘Any Site’

‘Any site’ means literally any and all sites.

Some Web developers may argue that their site has been created for a specific group

of people and therefore it is not necessary for their site to comply with our Web

accessibility definition. This argument fails on three counts, not counting any legal

ramifications. Firstly, any member of the intended audience may become disabled at

a future time, secondly, disabled users wishing to join this selected group are

prevented from doing so, and thirdly, users who may be interested in the subject

matter are prevented from accessing the information.

3.1.4 ‘Full and Complete Understanding’

There are approximately 6,800 spoken languages with a further 41,000 distinct

dialects. [33] Unfortunately the content of the vast majority of Web sites is written in

just one language. In the case of UCLAN that language is obviously English.

For many students English is not their first language yet, to comply with our

definition, all Web pages must be fully and completely understandable to them.

Some sites now use automatic language translation programs. For example, Google

now offer their search engine Web site in 53 languages and users can set their user

interface preference in one of 88 different languages. Google also offer a Web page

translation service in 12 languages. [34] Unfortunately the resulting translations are not

totally accurate and can confuse students.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-24-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

25

The following groups of people would benefit from having access to accessible Web

sites which comply with this definition. [35]

1. People who may not be able to see, hear, or move.

2. People who may not be able to process some types of information easily,

or at all.

3. People who have difficulty reading or understanding text.

4. People who do not have, or are not able to use, a keyboard or mouse.

5. People who have a text-only screen, a small screen, or a slow Internet

connection.

6. People who do not speak or understand the language in which the

document is written.

7. People who are in a situation where their eyes, ears, or hands are busy (e.g.

driving to work, working in a noisy / loud environment).

8. People who have an old version of a browser, a different browser entirely,

a voice browser, or a different operating system.

9. People who do not have access to audio speakers.

4.0 Compliance of Existing University Web Sites

4.1 University of Central Lancashire

UCLAN is assumed to be a typical UK University. It is also assumed that the

accessibility / inaccessibility of the UCLAN Web site will be fairly representative of

the vast majority of FE and HE institutions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-26-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

26

UCLAN is the sixth largest university in England with more than 26,000 students and

2000 staff. [36] Students can enrol on more than 550 courses with a further 3600

possible subject combinations - students can effectively design their own course.

UCLAN has 21 Partner Colleges and is also partnered with 120 institutions

worldwide. UCLAN currently has more than 2000 international students enrolled on

courses.

UCLAN has set a target of attracting 50,000 students by 2010. This doubling of

student numbers will necessitate a large increase in distance learning - the current

campus could not physically accommodate such an influx of students. Distance

learning, via the World Wide Web, will therefore be the main way of attracting new

students and is becoming a central part of the delivery of both on and off campus

learning programmes. Distance Learning programmes must be accessible to disabled

students.

4.2 UCLAN Web Site Audit

A brief audit of the UCLAN Web site in March 2003 identified more than 13000

corporate Web pages [37] as shown in Appendix B. These figures do not include

individual staff pages. A brief assessment of the site in September 2001, using

‘Bobby’ [38], highlighted the fact that more than 80% of the Web pages did not meet

the requirements of ‘WCAG A’, never mind the preferred ‘WCAG AA’ benchmark.

This situation has now largely been rectified and UCLAN aims to be fully ‘WCAG

AA’ compliant by September 2003.

This audit confirms Paciello’s assertion that the vast majority of Web pages were

technically illegal prior to SENDA. (See Section 5.1)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-27-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

27

5.0 Incidence of Disability

5.1 General Disability Statistics

It is very difficult to obtain accurate statistics regarding the incidence of disability.

According to Paciello [39]

there are approximately: -

1. 500 million disabled people worldwide

2. 8.5 million disabled people in UK

3. 52.6 million disabled people in USA

4. 37 million disabled people in EU

5. 4.2 million disabled people in Canada

6. 3.7 million disabled people in Australia

Temporary disabilities are NOT included in these statistics. Additionally, Paciello

estimates that between 95% and 99% of all Web sites are inaccessible.

5.2 Disabled Students in HE

According to the Higher Education Statistics Agency more than 30,000 students with

a disability started programmes of study in UK higher education institutions during

the 2000-01 academic year, representing over 4% of all new students. Of those

students with a disability, approximately 34% were dyslexic, 3% blind or partially

sighted, 7% deaf or hearing impaired, 5% were wheelchair users or had mobility

problems, 4% had mental health difficulties, 27% had an unseen disability, 6% had

multiple disabilities and 13% had some other disability. [40] These numbers probably

underestimate the total number of students who consider themselves to have a

disability, the numbers actually with a disability, and the numbers covered by

SENDA.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-28-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

29

According to the Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB) [41] there are more than

350,000 people in the UK who are blind or partially sighted, that is 1 person in 60 of

the whole population. Moreover, 6 out of 10 visually impaired adults have another

illness or disability.

Many people assume that visually disabled means total blindness. In fact only 18% of

the visually impaired are totally blind. Likewise, people assume that the visually

disabled can read Braille and have a guide dog. According to the RNIB only 19,000

people can read Braille and only about 4,000 people have a guide dog.

Users with visual disabilities will, to varying degrees, have difficulty seeing the

computer screen. This can range from total blindness where the user cannot see

anything, to somebody who is near or far sighted and therefore able to read the text

with the aid of spectacles or perhaps a screen magnifier. Some dyslexics have

problems with certain colour combinations, as do people with colour blindness.

There is a range of AT designed to help people who have trouble seeing the screen

including:

• Screen readers

o Dolphin Supernova

o Jaws

• Web browsers

o Cast E-Reader

o IBM Homepage Reader

• Refreshable Braille displays

• Voice recognition software

• Screen magnification software](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-30-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

30

In effect all of these AT solutions perform the same function; namely they convert on-

screen text into a format which can be understood by the disabled person.

Web developers can also code special ‘skip navigation’ links which provide a means

for visually disabled users to avoid the main navigation controls of a Web page and

jump straight to the main content of the page. This means that the visually disabled

user does not have to listen to the screen reader reading out the navigation links on

every page.

6.2 Aural Barriers to Access

This category includes people who have been deaf from birth, deafened people, and

those who have partial hearing. A deafened person is someone who was born with

hearing but then developed a hearing impairment later in life, perhaps as a result of an

illness or an accident.

According to the Royal National Institute of the Deaf (RNID) [42] 8.7 million people in

the UK have a hearing impairment, that is 1 in 7 of the whole population. This

number is rising as the number of people aged over 60 increases. About 698,000 of

these are severely or profoundly deaf, a high proportion of which have other

disabilities as well. There are an estimated 123,000 deafened people in the UK aged

16 and over.

4.7 million people, 1 person in 10, suffer from tinnitus [43] and 55% of all people over

60 years of age are deaf or hard of hearing. 25,000 children in the UK under the age

of 15 are permanently deaf or hard of hearing. There are also 23,000 deafblind people

in the UK. In the UK there are approximately 50,000 British Sign Language (BSL)

users. [44]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-31-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

31

The barriers to access faced by users with hearing difficulties depends, to a certain

extent, on whether the user has been deaf from birth or deafened later in life. It is

important from a Web developer’s perspective to differentiate between the two

groups.

Users who are deaf from birth communicate using BSL. BSL is a language in its own

right and has different grammar and structure to English. BSL users must learn

English in the same way that others may learn French or German. Web developers

cannot assume that BSL users can read and understand the content of their Web

pages.

There is an assumption that users who become deaf later in life can read and

understand English. It may be true in some cases but many of these users

communicate using Sign Supported English (SSE); a combination of BSL and

English.

Users with hearing difficulties require visual representation of auditory information

such as a transcript or captions. MAGpie [45] is a free piece of software enabling the

creation of captions and subtitles for, and integrating audio descriptions with, digital

multimedia such as video.

6.3 Physical Barriers to Access

This is a wide ranging category and includes people with a range of physical

disabilities including amputees, people who may have suffered a stroke, have spinal

cord injuries, lost the use of limbs or digits, and people with manual dexterity or

physical co-ordination problems.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-32-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

32

According to the United Medical and Dental Schools of Guy's and St Thomas'

Hospitals (UMDS) [46], Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME) is thought to affect about

2% of the UK population at any one time, one in 100 people over the age of 65 have

Parkinson's disease, and eight in 100 over the age of 65 are affected by Alzheimer’s

disease.

Most Web sites are created assuming that the user can see the screen and use a mouse.

Many physically disabled users cannot use a mouse. Many Web sites include links

which are extremely small. Again many physically disabled users, even if they can

use a mouse, cannot hold the mouse pointer steady for a long enough period of time to

enable them to select the link.

There are a number of AT devices available to help users with physical disabilities

including Retinal scanning devices and Voice Recognition software such as Dragon

Naturally Speaking [47] . In addition the Windows operating system has a number of

built-in accessibility features such as ‘sticky keys’. Sticky Keys allow users to select

keyboard combinations one key at a time.

In addition Web developers can add special code to their Web pages to allow

physically disabled users to navigate their site. This special code allows physically

disabled users to navigate via their keyboard using special access keys. Access keys

enable users to quickly visit key links within a site.

6.4 Cognitive Barriers to Access

‘Cognitive disability’ is any disability that affects mental processes including mental

retardation, attention deficit disorder, brain damage, dementia and other psychiatric

and behavioural disorders. This category also includes people with learning

difficulties and dyslexia / dyscalculia. People with learning difficulties may have](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-33-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

33

problems with literacy, information technology, and understanding information

generally. Dyslexia includes people who have problems reading, writing and spelling.

Dyscalculia describes people who have problems with mathematical calculations.

‘Mental load’ is also a factor; that is, the demands placed upon a person's cognitive

abilities when performing a task. This is a problem for all people, and especially for

users of AT. For persons with cognitive and/or behavioural disorders the problem is

magnified. Web designers should avoid using background images and music and

should use a consistent design layout. These measures will not only reduce mental

load for the cognitively disabled but will help all users to access their Web site.

There are over 200,000 people with severe learning disabilities in the UK and about 1

in 100 people suffer from dyslexia (boys are three times more likely to be affected

than girls).[48]

There is no specific AT available for people with cognitive disabilities although much

can be done to increase accessibility when designing the content of a Web site. For

example, users with learning difficulties may struggle to read long paragraphs or

certain fonts. This problem can be minimized by keeping paragraphs short and using

CSS. It is also difficult for some users with cognitive disabilities to read justified text

so text should be left justified. Flashing text should also be avoided as this can cause

certain people to have epileptic seizures.

The Plain English Campaign has produced a number of free guides [49] to help Web

developers produce accessible content for the cognitively disabled. Page content tips

include keeping the average sentence to between 15 and 20 words, using active rather

than passive verbs, using clear and helpful headings, and leaving plenty of

‘whitespace’ on the screen.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-34-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

34

6.5 Summary

The AFA project seeks to train Web developers to create Web sites which can cater

for the diverse needs of all users. Web developers must be aware of the various user

needs and the AT available to help such users.

It is relatively easy to create an accessible Web site for a user with a specific

disability. The problem is that Web sites must be accessible for all users, including

users with multiple disabilities.

It is also worth mentioning that this section has only covered user needs in a general

sense. Each user is an individual and may have very specific requirements. This

demonstrates how difficult it is to fully comply with the SENDA legislation.

7.0 Learning Theories, Styles & AFA Course Strategy

Students undertaking the AFA course must have a clear understanding of what it is

they are trying to learn. According to Tough [50] the most common motivation for

learning is that there is ‘an anticipated use or application for the skills learned’.

The original AFA course was delivered in an IT training lab, primarily in order to

evaluate the course and obtain feedback from participants. Future versions can easily

be incorporated into WebCT, the chosen virtual learning environment (VLE) at

UCLAN.

7.1 Learning Theories

There are numerous learning theories. The ‘Theory Into Practice Database’ lists

dozens of such theories. [51]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-35-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

35

7.1.1 Internet Based Learning

There are many benefits to Internet based learning [52]. It is flexible, students can learn

at times convenient to them and travel costs are substantially reduced. The student

can progress at his or her own speed and can complete the course material in any

order of their choosing.

However, not all students are suited for Internet-based education. Lack of motivation

can lead students to drop out, often because they feel isolated and lonely - they may

miss the personal interaction with other people. They may be worried about using

computer technology. The cost of computer equipment may also be a factor as will the

lack of technical support in the home.

The academic institution, and the course leader, may benefit from Internet-based

courses although there are problems as well.

Electronic information is cheap and easy to distribute; the cost of printing is

transferred to the student should they prefer printed materials. Accessible course

material can be viewed by students using a diverse range of computers and Internet

browsers. Material can be reused, re-packaged or archived.

Larger number of students can simultaneously take courses, a potential source of

revenue for the academic institution, and they are not limited by geographical

location. Electronic marking and evaluation is now possible substantially reducing the

course leaders’ workload.

On the other hand, many of the costs of setting up and developing online learning

courses are ’front loaded’; they need to be incurred before any income is generated.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-36-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

36

Many academic staff do not have the time, or incentive, to learn new technologies.

Problems with computer networks and unreliable equipment can prevent access to

course material.

Slow Internet connections can make some interactive multimedia applications too

slow for effective learning.

Internet-based technology allows students to learn according to their own learning

style. The use of images, multimedia, graphs, charts, audio, new programming

languages such as Mathematical Mark-Up Language (MML), Java applets etc. can be

combined to facilitate visual, aural, and kinesthetic learning styles.

NB. Visual learners learn by seeing, aural learners learn by hearing, kinesthetic

learners learn by touching and doing.

7.1.2 Open Learning

Maxwell has defined Open Learning as ‘a student centred approach to education

which removes all barriers to access while providing a high degree of learner

autonomy’. [53]

Internet-based learning supports the open learning concept by providing students with

the ability to connect to educational resources when it is convenient for them, and

allowing students to explore the educational resources in an order that suits their

needs. In an open learning environment the teacher acts as a tutor, facilitator, and

resource to assist in the student's learning process. [54]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-37-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

37

7.1.3 Situated Learning

Internet based learning encourages Situated Learning [55]. Situated Learning Theories

argue that learning is a function of the activity, context and culture in which it occurs.

This contrasts with much classroom learning activities which involve knowledge

which is abstract and out of context. Social interaction is a critical component of

situated learning because learning requires social interaction and collaboration. In the

AFA course users will actually build a real Website using real tools and real software.

Social interaction will occur naturally as students help each other. Ultimately users

will be able to rely on the help of the course leader.

7.1.4 Constructivism

The Constructivist Principles of Bruner [56] will also be embedded within the course.

A major theme in the theoretical framework of Bruner is that learning is an active

process in which learners construct new ideas or concepts based upon their current

and past knowledge. The learner selects and considers information from various

viewpoints, constructs hypotheses, and then makes decisions whilst relying on mental

models to do so. Constructivism allows users to experiment and learn without the fear

of failure. AFA users will be encouraged to employ constructivist principles

throughout the course.

7.2 Learning Styles

Students have different learning styles depending on their characteristics, strengths

and personality. Some students learn visually, others by hearing, still others

kinesthetically. The AFA project aims to take account of the different student needs

and approaches to learning. The goal is to ‘teach around the cycle’, that is, ensure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-38-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

38

that the learning materials in the AFA project cater for the needs of each type of

learning style.

Felder [57] considers various learning style models and concludes that, whichever

model is chosen, the learning needs of each student can be met if the correct teaching

strategy is followed. I will consider three models.

7.2.1 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI)

According to the MBTI model students may be:

1. extraverts who try things out or introverts who think things through;

2. sensors who are practical and focus on details and facts or intuitors who are

imaginative;

3. thinkers who are logical or feelers who tend to make intuitive decisions;

4. judgers who make and follow lists or perceivers who adapt to changing

circumstances.

These ‘types’ can be combined to form 16 different learning styles. For example, one

student may be an introverted sensor who feels and perceives; another may be an

extraverted intuitor who thinks and judges.

7.2.2 Kolb's Learning Style Model

This model classifies students as preferring to take information in via concrete

experience or abstract conceptualization, and then apply the information via active

experimentation or reflective observation. The four types of learners form a matrix as

follows.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-39-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

41

7.4 Summary

The AFA course is an ideal subject for an Internet based course. The diverse learning

styles of users can easily be accommodated via the Internet. The concept of open

learning using situated learning and constructivist principles is well suited to AFA.

To cater for all types of learners, the AFA course should explain the relevance of each

new accessibility topic, present the basic information and coding methods associated

with the topic in a variety of ways, provide opportunities for individual and group

practice in the methods, and then encourage users to explore the topic for themselves.

8.0 Accessible Web Site Resources

I have ascertained that FE and HE institutions have a legal obligation to produce

accessible online material and have defined precisely what an accessible Web site is.

I have also identified various groups of disabled users and the problems faced by

these groups when attempting to browse the Internet.

I will now consider what other learning resources are available to help Web

developers to create accessible Web sites.

There are literally thousands of Web sites with Web accessibility related information -

a search for ‘Web Accessibility’ on Google produced 425,000 results [58].

Unfortunately there are only a few books on the subject, perhaps because this subject

has only recently come into the public eye. Consequently, and perhaps surprisingly,

there are very few good Web accessibility resources which deal with the actual

creation of accessible Web sites. The majority of the sources are heavily slanted

towards compliance with Section 508 of the US Rehabilitation Act 1973.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-42-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

42

8.1 Books

Web Accessibility for People with Disabilities [59] was probably the first book on the

subject following the launch of the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI). The book

contains tips, tools, guidelines and HTML coding techniques to help make Web sites

accessible. The book also contains lots of useful accessibility related links from Web

sites all over the world.

Constructing Accessible Web Sites [60] has been written to enable Web developers to

create and retrofit accessible Websites quickly and easily. Whilst the objectives are

laudable the reality may not be quite so simple.

The book discusses the technologies and techniques that are used to access Websites

and many disability related legal guidelines, both in the US and around the world.

The main body of the book is concerned with making Web sites and their content

accessible. Sections include testing methods, development tools, and advanced coding

techniques. The book also contains a useful checklist for creating accessible Web

sites.

Maximum Accessibility [61] is another excellent book, similar to the above mentioned

books. One of the authors, John Slatin, writes from personal experience as he is

legally blind.

8.2 Web Sites

The ‘Curriculum for Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0’ [62] compiled by the

W3C WAI, comprises 4 main sections known as ‘sets’.

1. An Introductory section - "The Introduction Set";

2. Guidelines for Web Content Accessibility - "The Guideline Set";](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-43-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

43

3. Checkpoints for meeting the Guideline requirements - "The Checkpoint Set";

4. Examples for implementing the Checkpoints - "The Example Set".

This course comprehensively deals with each of the 14 WCAG guidelines and 65

checkpoints. However, the course is written in HTML rather than XHTML and

contains some poorly written code.

For example, the mark-up example for Checkpoint 5.1: the use of the ‘TH' element in

a TABLE uses the following code as an example. [63] The table contains several errors

and omissions. (The lines are numbered to aid my comments)

1. <TABLE border=1>

2. <CAPTION>Example of a simple data table created using HTML

markup. </CAPTION>

3. <TR>

4. <TD></TD>

5. <TH>Col. 1 header</TH>

6. <TH>Col. 2 header</TH>

7. </TR>

8. <TR>

9. <TH>Row 1 header</TH>

10. <TD>C1R1</TD>

11. <TD>C1R2</TD>

12. </TR>

13. <TR>

14. <TH>Row 2 header</TH>

15. <TD>C2R1</TD>

16. <TD>C2R2</TD>

17. </TR>

18. </TABLE>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-44-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

44

The first error is found on line 1. The code border=1 is missing quotation marks – it

should read border=”1”. The second error is found on line 4. Line 4 contains an

empty table cell which can cause problems when viewed using Netscape browsers.

The table does not contain the <thead> or <tbody> tags. These tags aid non-visual

users by providing structural information about the table.

The table tags are all in UPPERCASE which means that the page will not validate in

XHTML – tags should be lowercase.

Technically speaking this page would work in most modern browsers – they are

forgiving of errors and generally present the page OK. However, many of the new

browsing technologies would have problems with this code.

Jim Thatcher, one of the authors of Constructing Accessible Web Sites, has produced

an online Web accessibility course entitled ‘Web Accessibility for Section 508’. [64]

As the course title suggests this resource is heavily slanted towards American

legislation. As previously mentioned, compliance with American legislation would

not meet the needs of SENDA. (See Section 2.6) This course explains the problems

faced by disable Web users and provides contains numerous HTML code examples

for developers to follow.

The JISC funded Techdis service has produced a learning resource entitled ‘Seven

precepts of Usability and Accessibility’ [65]. The seven precepts cover a range of

usability and accessibility issues and each is accompanied by a short description. Each

precept is linked to detailed information about the concepts and coded examples are

provided to show Web developers how to apply the concepts to their Web site.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-45-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

48

9.1.4 Hardware

The minimum hardware requirements are based on the configuration of a typical

home computer user and the standard system requirements for Macromedia

Dreamweaver. [66] (see Section 11.4)

• Intel Pentium II processor or equivalent 300+ MHz

• 128 MB Ram

• 2GB Hard Drive

• 8 x CD Rom Drive

• Floppy Disc Drive

• 15” Colour Monitor capable of 800 x 600 resolution

• Windows 98 operating system or better

• Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer 4.0 or greater

• Colour Printer

• Keyboard and Mouse

9.1.5 User Tasks / Learning Objectives

1. Understand the problems faced by disabled people using the Internet, these are

known as ‘barriers to access’.

2. Understand how Web developers can code their Web pages to remove these

barriers to access. Specifically users will learn about:

1. Templates

2. Cascading Style Sheets

3. Document type definitions

4. Non-textual content

5. Tables](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-49-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

50

The user should be able to access the course from any environment, the only computer

requirements are that the user has Internet access and some form of Web browser.

9.2.1 Users Tasks / Learning Objectives

Again, according to our definition of Web accessibility in Section 3.0 our user, that is

anyone and everyone, should be able to get a ‘…full and complete understanding of

the information contained there, as well as have the full and complete ability to

interact with the site.’

10.0 Web Site Project Management

As mentioned in Section 8.3 the AFA project is unique and does not fit in with

traditional software engineering models. However, traditional models are tried and

tested and provide useful guidelines which may be applied in a Web-based project

setting.

10.1 Waterfall

The Waterfall model is a highly structured approach to project development.

Conventional software engineering is based on the assumption of a more or less

sequential development process [67]. The developer plans a number of project

development stages which are completed in a linear fashion. Upon completion of one

stage, the designer moves on to the next stage without having the opportunity to return

to previous stages. This method assumes that the developer is able to specify the

whole project in its entirety before commencing.

The uniqueness of the AFA project precludes the use of the Waterfall method. There

are no other Web sites which can be used as a template for the AFA project.

Additionally, there is not a definitive way of creating an accessible Web site. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-51-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

51

AFA project will evolve by a series of ‘trial and error’ prototypes which will be

refined following user testing and feedback.

10.2 System Assembly from Reusable Components

This method utilises the fact that many systems consist of a number of pre-existing

components which can be reused. This has the benefit of increasing productivity,

quality, reliability and, in the long-term, decreasing software development costs [68].

The principles outlined in this method can be implemented in the AFA project. The

main navigation and footer information could be included in a reusable template. The

developer can make the template fully accessible; pages based on the template will be

automatically accessible as well.

10.3 The Dynamic Systems Development Method

A fundamental assumption of DSDM is that nothing is built perfectly first time, but

that a usable and useful 80% of the proposed system can be produced in 20% of the

time it would take to produce the total system [69].

DSDM combines iterative prototyping and user participation. Unlike the Waterfall

method, DSDM allows previously completed sections to be changed in response to

user input. In terms of the AFA project, the users may not fully understand the

accessibility issues but they can provide useful feedback on the actual training

material.

10.4 Prototyping

A prototype is ‘a preliminary type, form, or instance of a system that serves as a

model for later stages or for the final, complete version of the system’ [70].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-52-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

52

There are basically two types of prototype used when developing Web-based projects

although the terminology can be confusing. One approach is to produce a ‘proof of

concept’ [71] throwaway prototype. This prototype is quickly constructed without the

developer needing to worry about coding problems, download times, image

optimisation and so on. A throwaway prototype is a non-functional mock-up that is

used to illustrate how a fully functional system will look or operate but which is not

intended to evolve into a fully working system.

The second option is to create a beta version of the final site including many of the

final design specifications, an ‘evolutionary prototype’. This prototype is intended to

form the basis of a fully functional working system and is a low quality version of the

final product.

10.5 Summary

Elements of each of the methods discussed, with the exception of the Waterfall

method, were used in the creation of the AFA project. Reusable components were

used in the creation of an evolutionary prototype, user feedback was then sought and a

further prototype built and tested. The final AFA version was then constructed.

11.0 Comparison of Web Authoring Tools

There are a numerous Web authoring tools for constructing Web sites. These range

from simple Text Editors such as Notepad [72] or BBEdit [73] to WYSIWYG editors

such as Macromedia Dreamweaver MX [74], Microsoft FrontPage 2002 [75] or Adobe

GoLive 6 [76].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-53-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

53

The final choice of software to create the AFA project is dependent on a number of

factors including the availability of the software on the UCLAN network, the

suitability of the software for the task in hand, and resources available in the event of

problems.

The text editors were quickly discounted for two main reasons. Firstly, many of the

prospective course participants would not be ‘fluent’ HTML coders; secondly the

time taken to hand-code a complete Web site would be prohibitive. Participants

should be able to complete the AFA course in one day.

A brief comparison of the three WYSIWYG Web authoring tools now follows. It is

interesting to note how the three software developers argue how their product is

superior to the others using selective feature comparisons and case studies. [77]

11.1 Macromedia Dreamweaver MX

Dreamweaver MX is one of the Macromedia Studio MX products. It is tightly

integrated with Fireworks, Flash and Freehand; each program uses the same panel

management system and user interface. The whole user interface is XML based and

therefore customisable.

Dreamweaver MX is the result of combining Dreamweaver and UltraDev. This means

that it is easy to create dynamic, database driven, Web sites using ASP, ASP.NET,

JSP, PHP or Cold Fusion. This ability is better than the same feature in GoLive 6,

where the application installs the dynamic application on the server itself.

Dreamweaver connects to the server faster than GoLive 6.

Dreamweaver now has a number of sample designs and pieces of reusable code called

snippets. This is in response to GoLive which has had these features for some time.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-54-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

54

Dreamweaver allows designers to create conditional nested design templates.

Incidentally, GoLive Web design templates are compatible with Dreamweaver,

The site definition wizard is OK for beginners but it is better to set up Web sites

manually.

Code Hints are an excellent new feature, especially for new HTML coders and those

developers who prefer to work in code view. Bradsoft TopStyle [78] can also be

integrated with Dreamweaver enabling designers to see the affects of CSS changes in

real time. Dreamweaver allows designers to easily code XHTML and includes an

automatic HTML to XHTML converter.

A major new feature is the built-in Web Accessibility checker. Accessibility code

prompts when inserting images, forms, frames and tables also aid developers.

In terms of help Dreamweaver is excellent. A number of reference libraries are

integrated within the product including HTML, CSS and JavaScript. Additional

support can be obtained via a newsgroup, [79] which has more than 395,000 messages,

and a plethora of online tutorials.

Dreamweaver can be extended using extensions. An extension is a piece of software

that can be added to Dreamweaver to enhance the application’s capabilities. There are

hundred’s of predominantly free extensions available. Developers can also write their

own extensions if necessary.

11.2 Microsoft FrontPage 2002

FrontPage 2002 uses the WYSIWYG simplicity of the word processor to creating

Web pages. Each new release becomes more and more like the other Microsoft Office

products.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-55-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

58

therefore break the WCAG guidelines. A full discussion of the WCAG guidelines

follows.

12.1.1 The World Wide Web Consortium

The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is an international industry consortium

jointly hosted by the MIT Laboratory for Computer Science in the USA, the National

Institute for Research in Computer Science and Control in France, and Keio

University in Japan. There are 450 member organizations of the Consortium. [80]

The W3C was created to lead the Web to its full potential by developing common

protocols (standards) that promote its evolution and ensure its interoperability

between WWW products.

The W3C provides a number of services including a collection of World Wide Web

resources for developers and users, reference code examples to represent and promote

standards and various prototype and sample applications to demonstrate use of new

technology.

12.1.2 The Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI)

The W3C are committed to the disabled and formed the WAI to promote Web

accessibility. The WAI is pursuing accessibility of the Web through five primary

areas of work:

1. addressing accessibility issues in the technology of the Web;

2. creating guidelines for browsers, authoring tools, and content creation;

3. developing evaluation and validation tools for accessibility;

4. conducting education and outreach;

5. tracking research and development.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-59-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

59

12.1.3 Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

There are two versions of WCAG. WCAG 1[81] contains a total of 65 guidelines;

WCAG 2 has reorganised and combined many of the WCAG 1 guidelines to create 21

new ones.

There are 14 main WCAG guidelines as follows: -

1. Provide equivalent alternatives to auditory and visual content.

2. Don't rely on colour alone.

3. Use mark-up and style sheets and do so properly.

4. Clarify natural language usage

5. Create tables that transform gracefully.

6. Ensure that pages featuring new technologies transform gracefully.

7. Ensure user control of time-sensitive content changes.

8. Ensure direct accessibility of embedded user interfaces.

9. Design for device-independence.

10. Use interim solutions.

11. Use W3C technologies and guidelines.

12. Provide context and orientation information.

13. Provide clear navigation mechanisms.

14. Ensure that documents are clear and simple.

More detailed information is given in Appendix C. Each guideline has a one or more

‘checkpoints’ that developers need to consider to ensure the accessibility of a Web

page. Each checkpoint has a priority level based on its impact on accessibility.

The WCAG provides a number of examples and techniques to help developers to

implement the guidelines.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-60-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

60

12.1.4 WCAG Priorities

There are 3 WCAG priority levels. [82] Compliance with the recommendations of each

level ensures greater accessibility of Web pages. The ‘Access for All’ project aims to

enable Web developers to produce WCAG AAA compliant sites.

12.1.4.1 Priority 1

Web developers MUST satisfy these checkpoints or some groups of people will find it

impossible to access information on their site. This is considered to be the absolute

minimum level of compliance.

12.1.4.2 Priority 2

Web developers should satisfy these checkpoints or some groups of people will find it

difficult to access information on their site. This is considered to be the preferred level

of compliance.

12.1.4.3 Priority 3

If Web developers satisfy these checkpoints the majority of users will be able to

access ALL of the information on their site. This is considered to be the optimum

level of compliance.

12.1.5 WCAG Conformance

The WCAG guidelines have three levels of conformance. [83]

1. Conformance Level "A": all Priority 1 checkpoints are satisfied. This is

known as WCAG A compliant.

2. Conformance Level "Double-A": all Priority 1 and 2 checkpoints are

satisfied. This is known as WCAG AA compliant.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-61-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

61

3. Conformance Level "Triple-A": all Priority 1, 2, and 3 checkpoints are

satisfied. This is known as WCAG AAA compliant.

12.1.6 Browser Specifications

Normally when creating a design specification Web server logs are examined to

ascertain the types of browser equipment and configuration used by site visitors. As

mentioned previously, the AFA project must cater for the needs of all users using all

types of browser software.

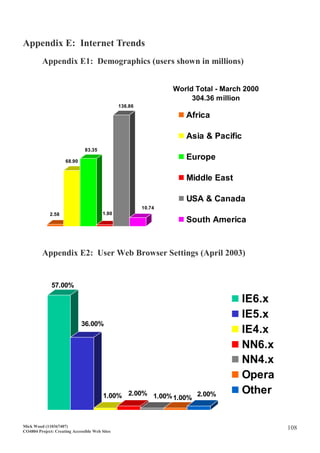

For the sake of completeness Appendix E contains the latest browser statistics. In

summary, there are more than 300 million Internet users worldwide. Over 90% of

them use Internet Explorer 5.x or better; 96% use a screen resolution of 800x600

pixels or larger; over 90% use Windows 98 or better; 64% now use a 56K modem or

better to connect to the Internet, and 90% use a monitor with a colour depth of 16-bit

or better.

12.1.7 Dept of Physics, Astronomy & Mathematics

It is perhaps more relevant to consider the types of users who visit the UCLAN Web

site. A survey of the Department of Physics, Astronomy and Mathematics (DPAM)

Web site was undertaken on behalf of the UCLAN Web Strategy Group in September

2001 and updated in March 2003. A summary of the findings are shown in Appendix

F. A typical visitor to the DPAM Web site originates from the United Kingdom, uses

Windows 98 or better, and browses using Internet Explorer 5.x or better. This is based

on an average hit rate of approximately 200 per week although there are clear

seasonal fluctuations [84]. These findings are consistent with the worldwide statistics

mentioned in Section 12.1.6.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-62-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

62

12.1.8 Summary

The AFA retro-fitted Web site will be coded to comply with WCAG 1 and have a

‘Triple-A’ conformance level. The course notes will provide a step-by-step guide,

enabling Web developers to produce technically accessible sites. Each developer can

choose to create Web sites compliant with any of the three conformance levels.

12.2 Colour [85]

Colour vision deficiency reduces the user’s ability to discriminate between colours on

the basis of three attributes; hue, lightness and saturation. Designers can help to

compensate for these deficits by making colours differ dramatically in all three

attributes.

Partial sight and congenital colour defects produce changes in perception that reduce

the visual effectiveness of certain colour combinations. Two colours that contrast

sharply to someone with normal vision may be far less distinguishable to someone

with a visual disorder.

The differences between the background and foreground colours must be exaggerated

and colours of similar lightness must be avoided, even if they differ in saturation or

hue.

Figure 1: Background Contrast](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-63-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

65

12.3.1 The screen layout will be consistently formatted

According to Detweiler and Omanson [86], the more consistent a Web site is in its

design, the easier it will be for users to navigate. Users, particularly older users, tend

to learn and remember the location of key functions and controls.

Screen layout includes logos, navigation buttons and footer information. Putting the

logo in a consistent place on every page ensures that users are fully aware that they

are on the same site.

12.3.2 Page sizes will be limited to 30K

As Appendix E5 shows, 36% of Internet users still use modems with connection

speeds of 33K or less. Pages will therefore be kept to a maximum of 30K ensuring

download times of less than ten seconds for these users. Visitors may not wait for

pages to load if they take too long to download [87].

12.3.3 Frames will not be used

Frame-based sites can be confusing for the visually disabled, particularly those using

screen readers or speech browsers - users can easily become disorientated.

Additionally, users cannot easily bookmark individual pages within a frame-based

site.

12.3.4 Paragraphs and sentences will be kept short

Readability improves when sentences and paragraphs are kept relatively short. Users

tend to scan Web pages and will often skip over large chunks of text [88].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-66-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

66

12.3.5 Each page will have a descriptive and different

title, a clear heading and logical structure

Titles are used by search engines to identify Web pages, if two or more pages have the

same title, they cannot be differentiated by users. Each page will also have clear and

helpful headings. Pages will be structured logically.

12.3.6 Font Guidelines

Font tags will not be used; instead Cascading Style Sheets will format the Web pages.

Fonts will be the equivalent of size 12pts to enhance reading performance [89].

Research has shown that there is no noticeable difference in reading speed or user

preferences between Times New Roman, Georgia or other serif fonts and Helvetica,

Verdana or other sans-serif fonts [90].

12.3.7 Links will be clearly identified

Blue underlined text will be used for all links. Some users miss links because the text

is not underlined. Research shows that users can easily find links which include

visual cues, that is, links that are underlined, rather than having to move the mouse to

see when the pointer changes to a hand (this is known as mine sweeping). Links will

not be designated with the text click here. Some screen readers can be set to read out

a list of links on a particular page; a list of click here links is not helpful [91]. Visited

links will be designated using a different colour. Many users use link colours to

identify which parts of a site they have already visited [92].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-67-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

73

that it linearises correctly. No structural tags were used for visual purposes (WCAG

5.4 – Priority 2).

Screen readers will eventually be able to read the table summary and this information

will enable the visually disabled to decide whether they want to access the table

contents. Table summaries can also help a person to interpret a particularly complex

or difficult table.

Some versions of Netscape contain a bug that may cause Web pages to display

incorrectly when the window is resized. Dreamweaver includes a piece of JavaScript

that automatically reloads the page whenever the window is resized. This is known as

the ’Netscape Resize Fix’. The fix was added to the page. In addition the following

code was manually added to the template in order for the page to validate properly:-

<script language="JavaScript" type="text/javascript">

The next stage was to add a 'skip navigation' text link immediately to the right of the

AFA logo. This allows users with a screen reader to jump straight to the page content

without having to listen to the navigation links being read out to them on each page

(WCAG 13.6 – Priority 3). The link will take them to a named anchor tag just before

the start of the main page content.

As the AFA logo is a link back to the home page this would mean that there are two

links immediately next to each other. This can cause problems to some screen readers

as they have a tendency to concatenate the links and they can become confusing.

Therefore the links need to be separated from each other by something other than

white space. The WCAG curriculum recommends the | symbol (WCAG 10.5 –

Priority 3). [93]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-74-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

76

Finally, the page contains misused header tags. In HTML there are six levels of

header tags ranging from <h1> to <h6>. The text gets progressively smaller as the

header value increases. Many Web developers use the header tags as text modifiers

when they should be used to structure the document. The headers in the index page

were correctly formatted.

Following the deletion of the splash screen home.htm was renamed index.htm, the

default name for a homepage on the UCLAN server.

13.4 Accessible Tables – table.htm

In addition to those learned on other pages table.htm contains a number of new

techniques.

Clear writing aids all site visitors regardless of cognitive ability. Sentences should be

clear and concise because people with dyslexia have difficulty understanding complex

passages (WCAG 14.1 – Priority 1). Three examples of poorly written sentences were

copied from the Campaign for Plain English Web site [94]. Participants will be invited

to re-write the sentences, either individually or in groups, to produce more

meaningful, user-friendly content.

There are no specific guidelines for creating and wording links. It makes sense to have

clearly worded text links, particularly for users of AT. Links should make sense out of

context because most screen readers and talking browsers scan a Web page for all the

links and create a list of the links for their users. Links such as ‘click here’ are

meaningless in a list of links. AT’s inform the user that text is a link, either by

changing pitch or voice, or by prefacing or following the text with the word ‘link’.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-77-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

80

paintings in more detail (WCAG 1.1 – Priority 1). The LONGDESC attribute is

unsupported in Dreamweaver so the HTML code must be edited directly.

Long descriptions are extremely difficult to write and time consuming. If you take the

Mona Lisa as an example, how can we describe this picture in words? To a certain

extent the answer to this question is dependent on the purpose of the image on the

page. If the image is decorative the visually disabled are not really disadvantaged by

not seeing the image. On the other hand, the image may be a fundamental part of a

particular page and therefore require a detailed description. In the case of Monet’s

Waterlilies how can we describe a predominantly blue picture? Will a visually

disabled person understand the concept of blue? How do you describe the colour

blue?

The author has not really got a definitive answer to this problem. Technically it is

quite easy to create a link to a long description page. In the case of the paintings it

would probably require the input of a subject expert to provide a meaningful long

description. The participants are asked to try and write a long description of these

paintings as a way of highlighting the problems.

This page also includes a number of foreign language quotations. Changes in the

natural language of a document must be highlighted by using the LANG attribute

(WCAG 4.1 – Priority1).

Current browsers are not known to support the language attribute but w3c.org

recommends placing foreign language quotes within <span> tags [95]. For example

<span lang="fr">Bonjour</span> [96].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4dbff53e-8216-4a6f-84e4-c5dec8464a89-151118114114-lva1-app6891/85/Creating_Accessible_Websites_Mick_Wood_MSc-81-320.jpg)

![Mick Wood (110367407)

CO4804 Project: Creating Accessible Web Sites

91

Thirdly, the text navigation links in the footer of the page are separated by a bar and

invisible text. The bar should be replaced by a transparent gif; the text should be made

visible.

These three ‘errors’ will be rectified in future versions of the AFA course.

16.2 Usability Testing