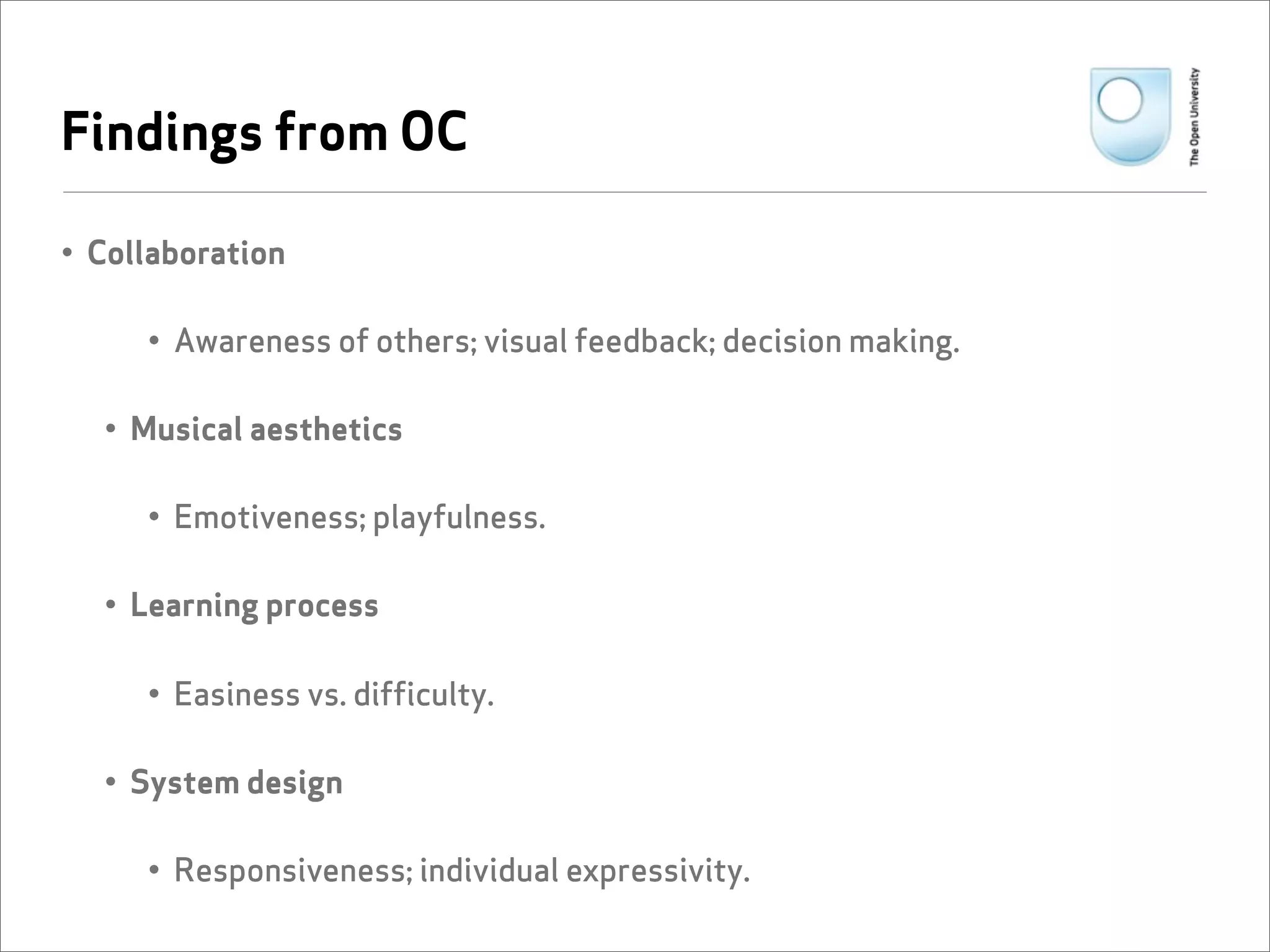

This document summarizes research into collaborative music making using multi-touch surfaces. It describes a study with 12 participants testing a simple music prototype. The study found that the prototype facilitated conversation and group productivity between participants, even for novices. It also provided evidence that roles were shared between participants rather than one person dominating. Future work could improve responsiveness and add both shared and individual controls to better support experts and novices.

![Musical multi-touch surfaces

• Audiopad [1], 2002, selection and edition of loops.

• Reactable [2, 3], 2004, modular synthesizer.

• Composition on the Table [4], 1998, audio-visual creation.

• Stereotronic Multi-Synth Orchestra [5], 2009, concentric seq.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-7-2048.jpg)

![Creative engagement

• Understanding creativity

• Psychological perspective of “flow” or full immersion in an activity

(Csikszentmihalyi [6]); the experience of fun and pleasure (Blythe and

Hassenzahl [7]).

• Creativity in group

• In the collective music composition attunement to others’ contributions

(Bryan-Kinss et al. [8]); “flow” extended to group productivity (Sawyer [9]).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-8-2048.jpg)

![Design considerations

• Multi-user instruments ([10], [11], [12])

• Shared vs. local control; complexity vs. simplicity.

• Multi-touch interaction [13])

• Discrete vs. continuous actions; display size; sense of touch; multiplicity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-9-2048.jpg)

![Method

• Iterative process: Design -> Evaluation -> Design

• User study

• Participants: 12 people, 3 groups of 4 users (music skills: G1=16/20, G2=8/20, G3=9/20).

• Video recordings: 3 musical tasks + informal discussion.

• Questionnaire.

• Data analysis

• Open coding (derived from GT [14]).

• Structured coding (derived from qualitative CA [15]).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-10-2048.jpg)

![Findings from structured coding

• Codes used

• Codes from [16]: tangible manipulation (consistent physical-digital), spatial

interaction, embodied facilitation (affordances), expressive representation

(legibility).

• Codes from [8]: mutual awareness, shared representations (collective

legibility), mutual modifiability (level of democracy), annotation (opinions).

• Results

• Consistent evidence: some content already discussed in the OC.

• New: multiple access points; shareable controls; conversations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-12-2048.jpg)

![References

[1] J. Patten, B. Recht, and H. Ishii, “Audiopad: a tagbased interface for musical performance,” in NIME ’02: Proceedings of the 2002 conference on

New interfaces for musical expression, (Singapore), pp. 1–6, National University of Singapore, 2002.

[2] S. Jordà, M. Kaltenbrunner, G. Geiger, and R. Bencina, “The reacTable*,” in Proceedings of the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC

2005), (Barcelona, Spain), 2005.

[3] S. Jordà, G. Geiger, M. Alonso, and M. Kaltenbrunner, “The reacTable: Exploring the synergy between live music performance and tabletop

tangible interfaces,” in TEI ’07: Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Tangible and embedded interaction, (New York, NY, USA), pp.

139–146, ACM, 2007.

[4] T. Iwai, “Composition on the table,” in International Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH: ACM Special

Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, ACM, 1999.

[5] http://www.fashionbuddha.com/, 15/3/2010.

[6] M. Csikszentmihalyi, Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play. Jossey-Bass, 1975.

[7] M. Blythe and M. Hassenzahl, The semantics of fun: differentiating enjoyable experiences, pp. 91–100. Norwell, MA, USA: Kluwer Academic

Publishers, 2004.

[8] N. Bryan-Kinns and F. Hamilton, “Identifying mutual engagement” Behaviour and Information Technology, 2009.

[9] K. Sawyer, Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration. Basic Books, 2007.

[10] [2] S. Jordà, “Multi-user instruments: models, examples and promises,” in NIME ’05: Proceedings of the 2005 conference on New interfaces for

musical expression, (Singapore, Singapore), pp. 23–26, National University.

[11] R. Fiebrink, D. Morris, and M. R. Morris, “Dynamic mapping of physical controls for tabletop groupware,” in CHI ’09: Proceedings of the 27th

international conference on Human factors in computing systems, (New York, NY, USA), pp. 471–480, ACM, 2009.

[12] T. Blaine and S. Fels, “Contexts of collaborative musical experiences,” in NIME ’03: Proceedings of the 2003 conference on New interfaces for

musical expression, (Singapore, Singapore), pp. 129–134, National University of Singapore, 2003.

[13] B. Buxton, Multi-Touch Systems that I Have Known and Loved. Microsoft Research, 2007.

[14] J. Lazar, J. Feng, and H. Hochheiser, Research Methods in Human-Computer Interaction. Wiley, 2010.

[15] D. L. Altheide, “Ethnographic content analysis,” Qualitative Sociology, vol. 10, pp. 65–77, 1987.

[16] E. Hornecker and J. Buur, “Getting a grip on tangible interaction: A framework on physical space and social interaction,” in CHI ’06: Proceedings

of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in computing systems, (New York, NY, USA), pp. 437–446, ACM Press, 2006.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crcpresentation2010-100608045302-phpapp02/75/CRC-PhD-Student-Conference-2010-Presentation-16-2048.jpg)