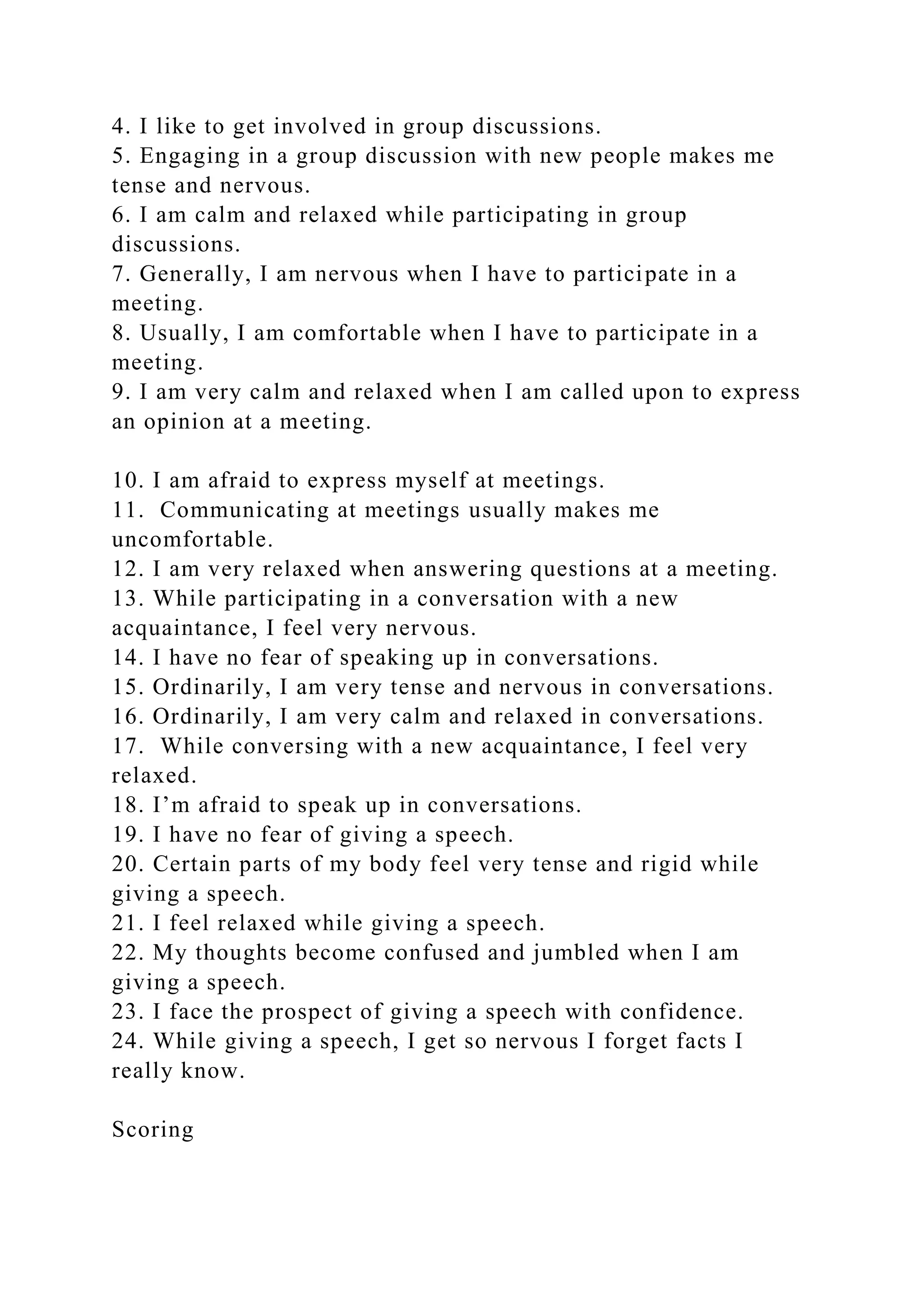

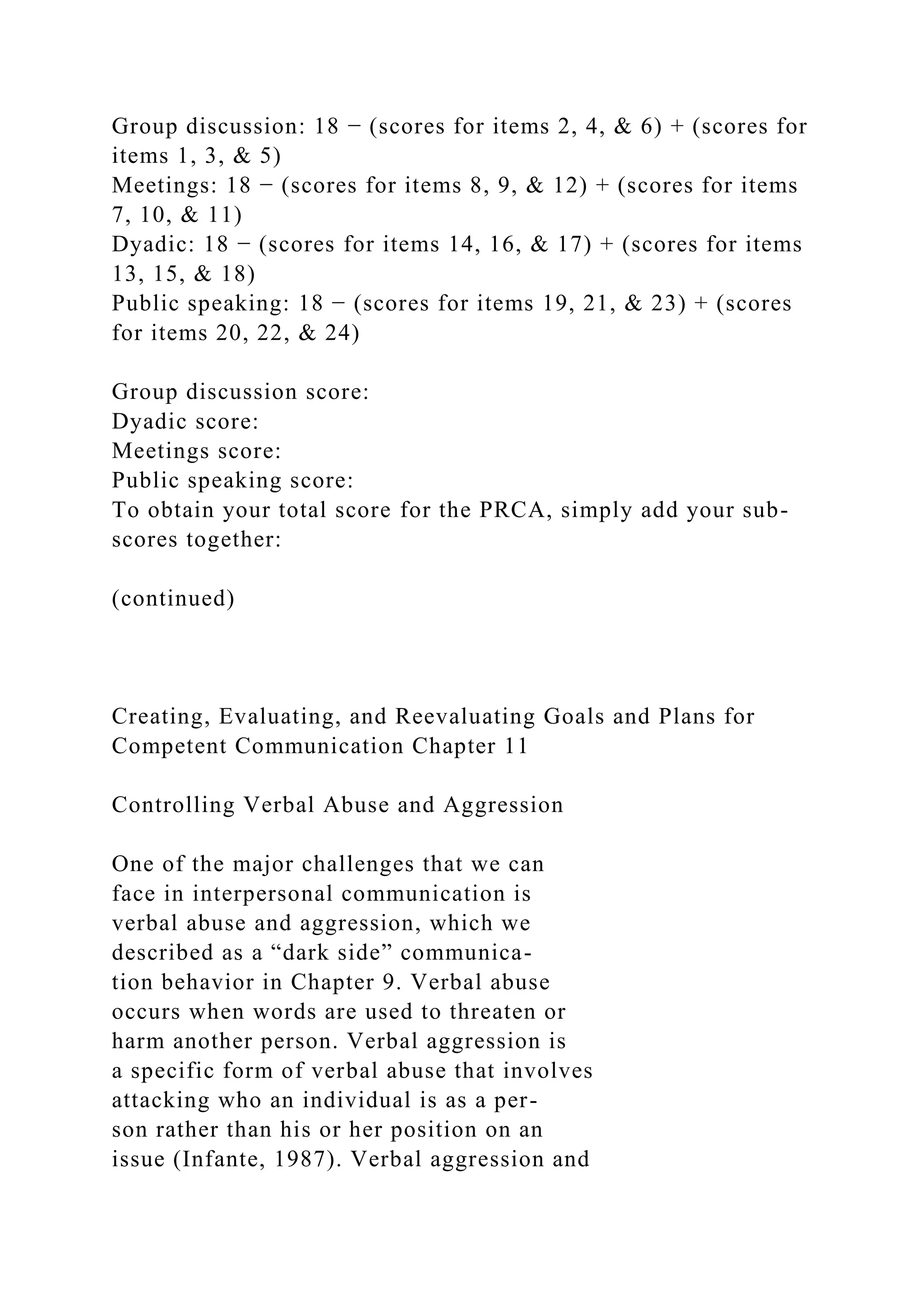

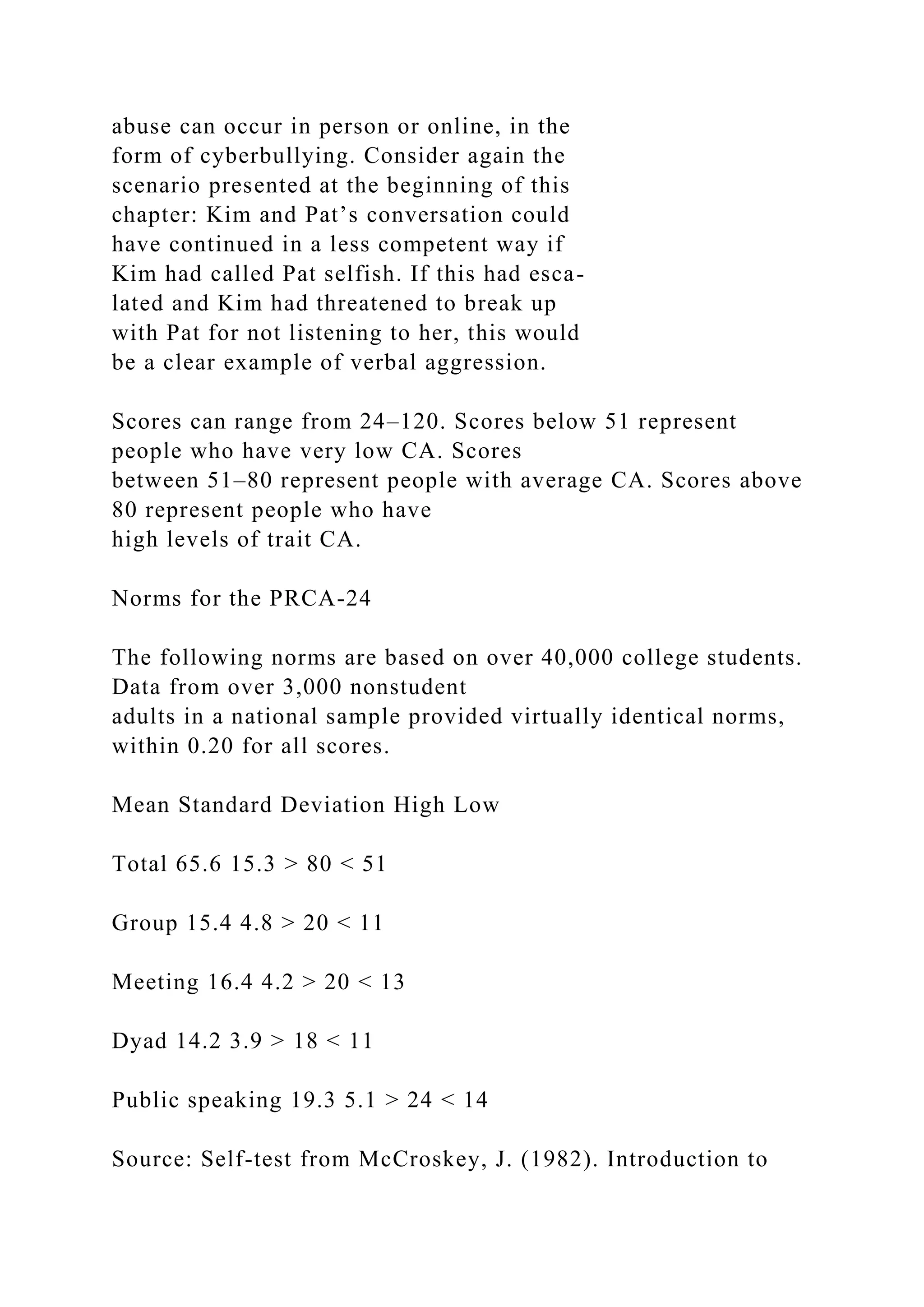

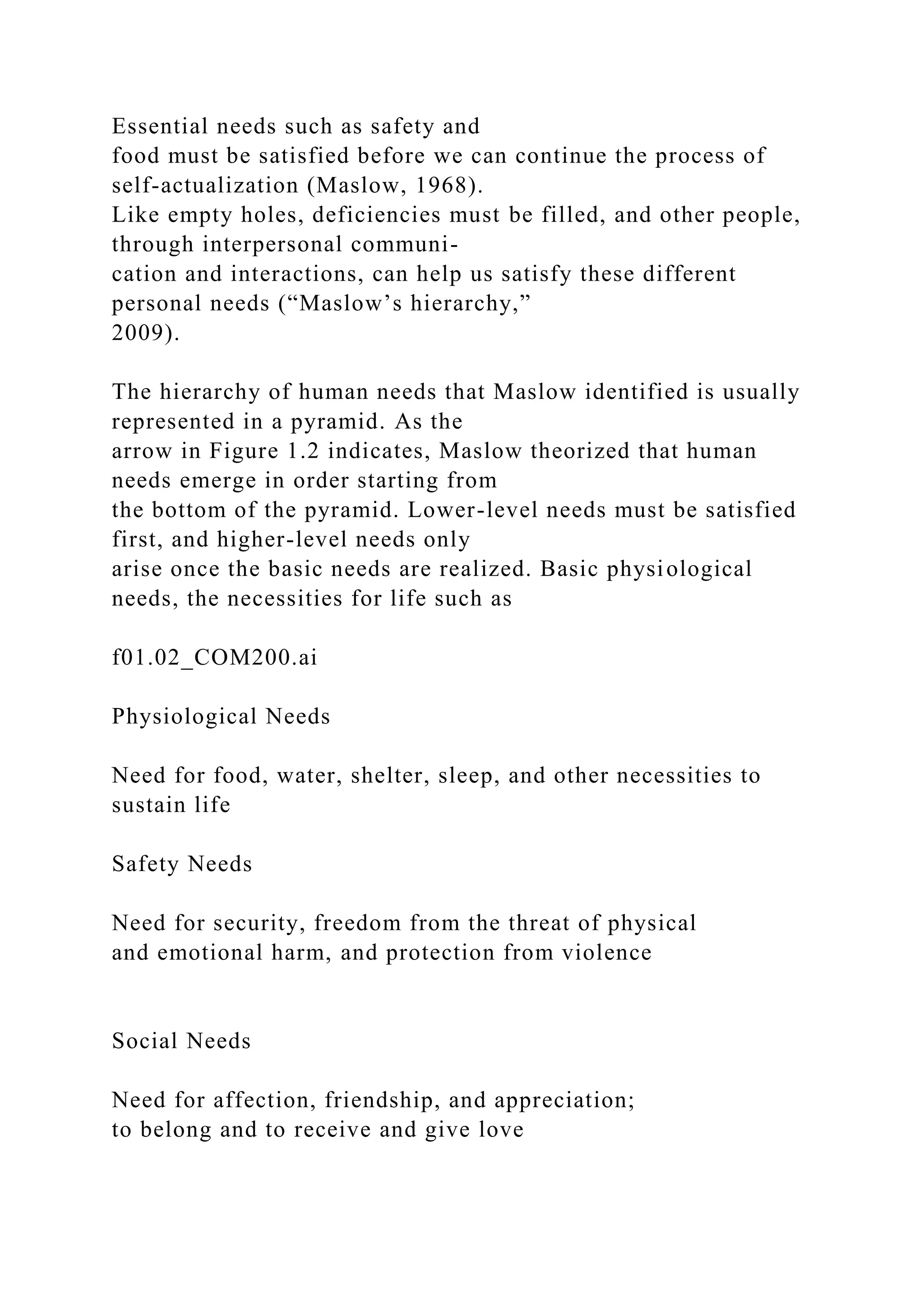

The document outlines a writing paper focused on comparing and contrasting two texts while exploring the concept of happiness through personal views. It emphasizes the importance of using personal experiences and critical thinking to define what constitutes 'a good life,' integrating quotations from the assigned readings. Additionally, it delves into self-concept and intrapersonal communication in relation to how individuals perceive themselves and communicate with others.