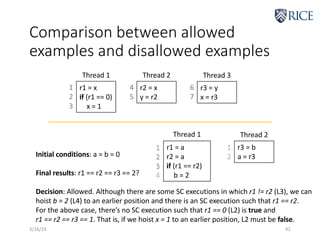

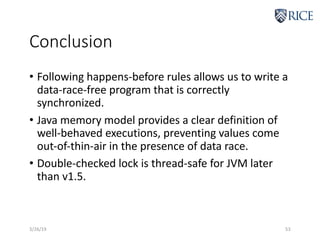

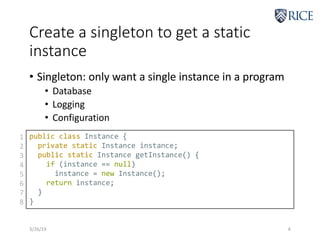

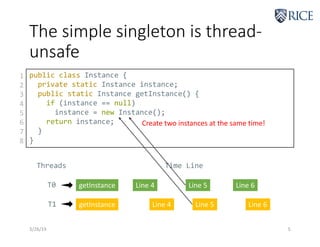

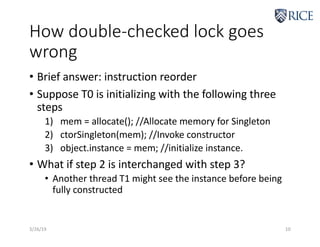

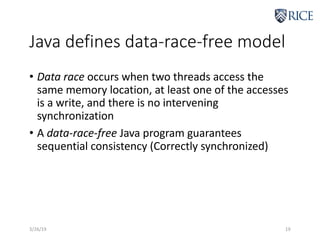

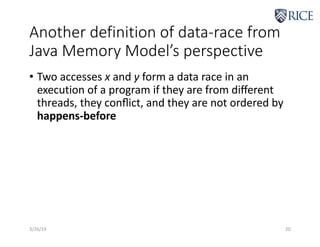

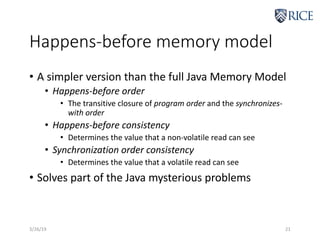

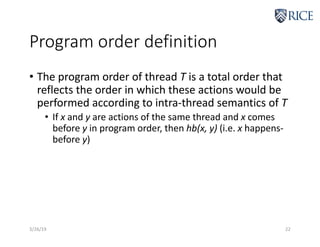

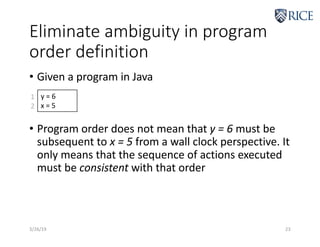

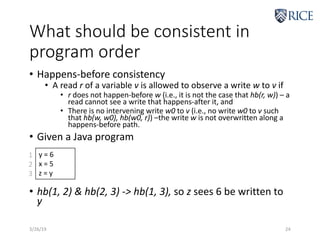

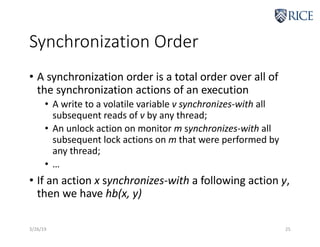

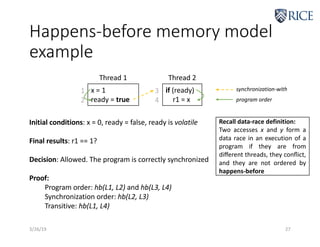

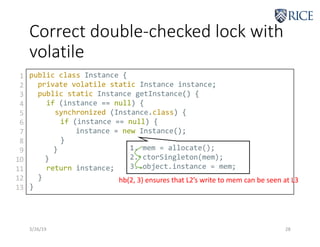

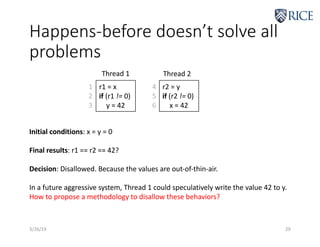

The document discusses the Java memory model and how it defines the semantics of multi-threaded Java programs. It explains that the memory model specifies legal program behaviors and provides safety and security properties. It then discusses different aspects of the memory model at varying levels of expertise, including how to properly use monitors, locks, and volatile variables, how to reason about program correctness, and how to optimize concurrent data structures and utilities. The document also covers topics like the happens-before consistency model and how volatile variables can be used to avoid issues like those in double-checked locking implementations.

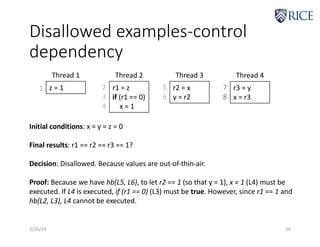

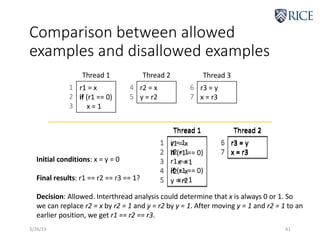

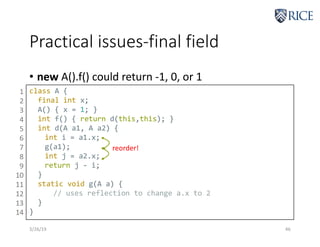

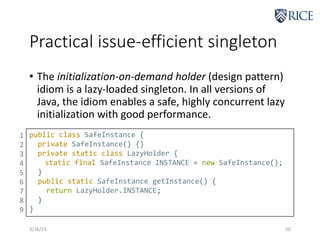

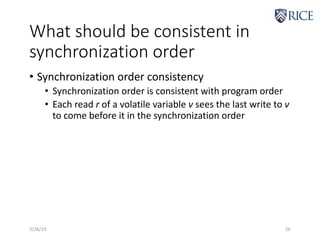

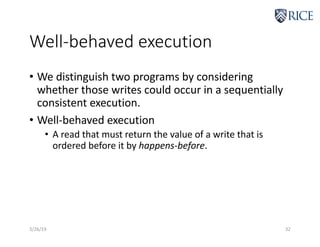

![Disallowed examples-data

dependency

3/26/19 33

r1 = x

a[r1] = 0

r2 = a[0]

y = r2

r3 = y

x = r3

Thread 1 Thread 2

1

2

3

4

5

6

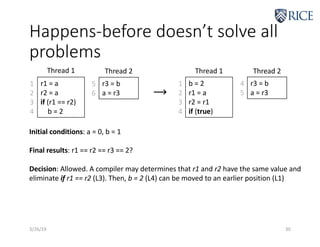

Initial conditions: x = y = 0; a[0] = 1, a[1] = 2

Final results: r1 == r2 == r3 == 1?

Decision: Disallowed. Because values are out-of-thin-air.

Proof: We have hb(L1, L2), hb(L2, L3). To let r2 == 1, a[0] must be 0. Since initially

a[0] == 1 and hb(L2, L3), we have r1 == 0 at a[r1] = 0 (L2). r1 at L2 is the final value

Because hb(L1, L2), r1 at L2 must see the write to r1 at r1 = x (L1).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/comp522-2019-java-memory-model-230209201934-e3d0d463/85/COMP522-2019-Java-Memory-Model-pdf-33-320.jpg)