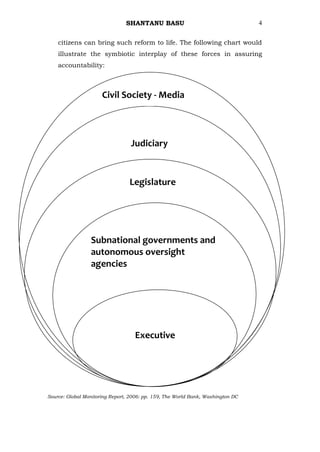

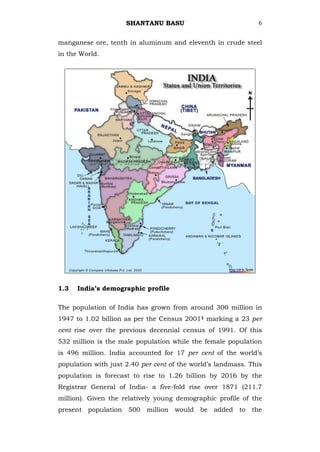

The document discusses strategies for combating corruption in India's established democracy. It aims to analyze corruption in seven key public sectors and suggest reforms. Unlike newer nations, India has well-established governance institutions but corruption has hindered development. The research will examine corruption levels and their impact on economic growth. It argues comprehensive reforms are needed across government, politics, and society to substantially reduce corruption.

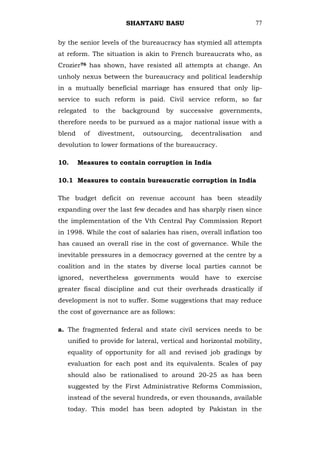

![SHANTANU BASU 28

Prime

Minister

Cabinet

Minister

Minister of Secretary

State

Secretary Same as for the other Secretary

Additional Secretary/Jt.

Secretary

Director/Dy.

Secretary

Under

Secretary

Section

Officer

Clerical staff

Chairperson, Advisory Councils

Directors-General Central Police Forces [Home only]

Autonomous body CEOs

Public sector CEOs

Average: Secretaries (2-3); Addl. Secretaries: 1-2; Jt. Secretaries: 5-7; Directors/Dy.

Secretaries: 10-15; Under Secretaries: 15-20; Section Officers: 15-20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combatingcorruptioninindiasomesuggestions-100719051201-phpapp02/85/Combating-corruption-in-india-some-suggestions-28-320.jpg)

![SHANTANU BASU 30

take the steel frame out, the fabric will collapse‖. This

perception did not change even with post-independence leaders

of the stature of Jawaharlal Nehru (India‘s first Prime Minister

1947-64) and Vallabh Bhai Patel (India‘s first Home [Interior]

Minister 1947-50). This was perhaps on account of the

bureaucracy and the political leadership sharing a common

social and cultural background42. Wedded to the Weberian

characteristics of hierarchy, status and rigidity of rules and

regulations and concerned mainly with the enforcement of law

and order and collection of revenues, the Indian bureaucracy in

its colonial form did not fit into the priorities of a developing

state.

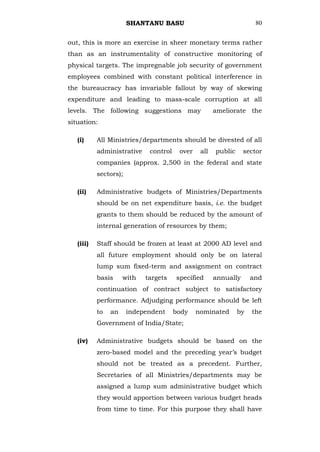

Up to the 1930s the Indian bureaucracy was well-paid even by

contemporary international standards as Potter43 has shown in

the following table:

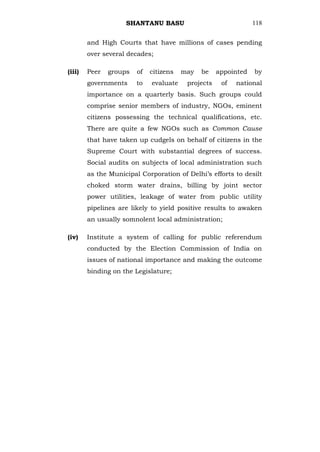

Top Indian Civil service Monthly pay Comparative Posts Monthly pay

Posts

(In Rupees) (In Rupees)

Governor of United Provinces 10,000 - -

Governor of Bihar 8,333 Governor, New York State 5,687

Member Viceroy‘s Council 6,666 Cabinet Minister, UK 5,555

Governor of Assam 5,500 Chief Justice, US Supreme 4,550

Court

Secretary, Govt. of India 4,000 Treasury Secretary, UK 3,333

Chief Secretary, Madras 3,750 Cabinet Member, USA 3,412

Commissioner, Bombay 3,500 President, Poland 1,560

Chief Secretary, Bihar 3,000 Governor, South Dakota 682

Secretary, Madras 2,750 Prime Minister, Japan 622](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combatingcorruptioninindiasomesuggestions-100719051201-phpapp02/85/Combating-corruption-in-india-some-suggestions-30-320.jpg)

![SHANTANU BASU 33

Indian bureaucracy‘s inability to deal effectively with the

complexities and ravages of a post-Partition (1947) India

stemmed from the facts that they were ill-equipped both by

training and mindset to cater to the wave of rising expectations

of a newly independent population in a democratic polity. Nor

did they possess what Bhatt45 quantifies as the sole objective to

―emphasize results, rather than procedures, team-work rather

than hierarchy and status, [and] flexibility and decentralisation

rather than control and authority‖.

It was quite unlike what Woodrow Wilson in his seminal essay

on ‗The Science of Administration‘ (1887)46 had envisioned the

role of government:

“There is scarcely a duty of government which was once simple

which is not now complex; government once had but a few

masters; it now has scores of masters. Majorities formerly

underwent government; they now conduct government. Where

government once might follow the whims of a court, it must now

follow the views of a nation.”

This essay was written when there was a public outcry against

corruption, improvement of efficiency and streamlining of

service delivery in the pursuit of public interest – a scenario that

is being presently repeated in India. Therefore it is imperative

that the Indian bureaucracy, as Esman47 says, accepts its

limitations and works in tandem with community and private

agencies. In a similar vein, Chambers48 describes the need for

‗bureaucratic reversals‘ in most situations where officials know

less than their clients; professionals should move from being

experts transferring information to become consultants and

collaborators of the poor. Disillusionment with the bureaucracy

and its inability to deliver on promises has fuelled demands

from a section of academia that sees non-governmental](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/combatingcorruptioninindiasomesuggestions-100719051201-phpapp02/85/Combating-corruption-in-india-some-suggestions-33-320.jpg)