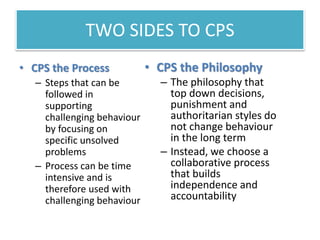

This document describes the collaborative problem solving (CPS) process and provides an example of how it was applied with a student named Juaquin. CPS is an alternative to top-down decision making that aims to build independence by engaging collaboratively to solve problems. The example shows how Juaquin was initially reluctant to write in his journal, but through empathetic conversation the underlying problem was identified as hunger. Offering a quick snack proved to be a mutually agreeable solution that addressed both the student and teacher's needs in a sustainable way, unlike coercive approaches that only solve short-term compliance issues.