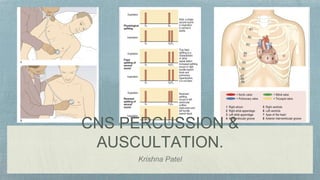

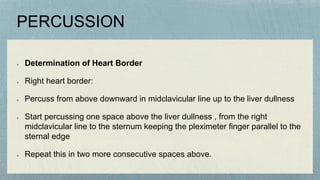

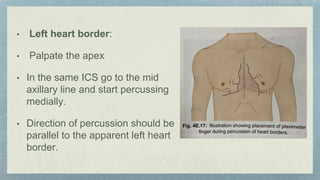

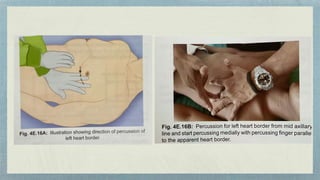

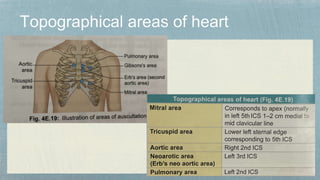

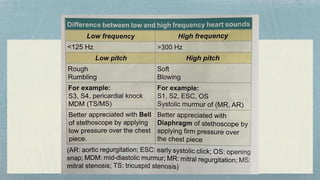

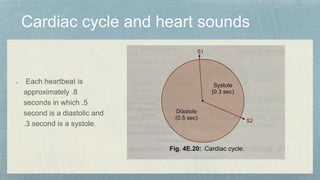

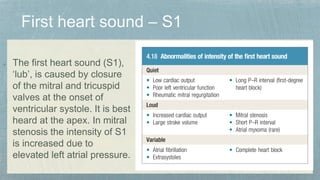

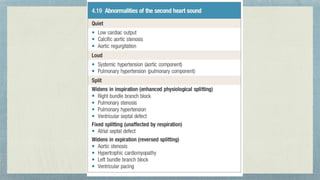

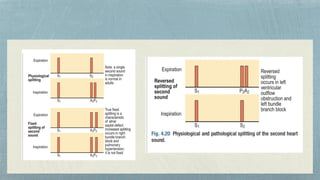

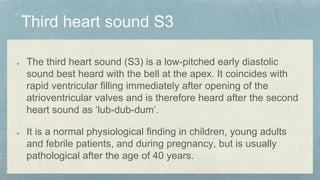

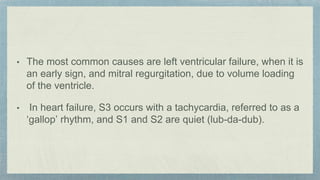

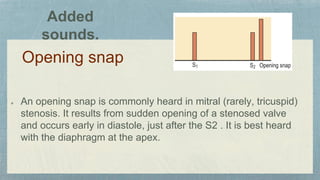

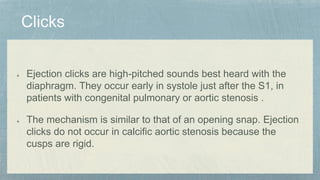

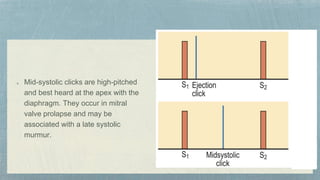

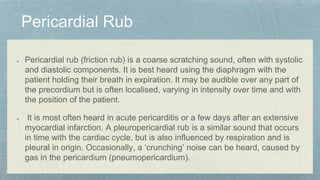

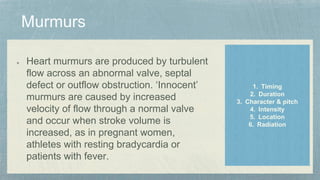

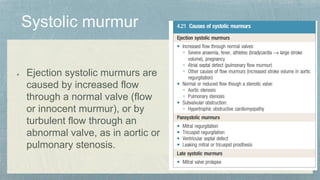

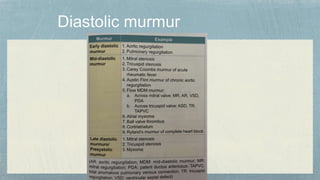

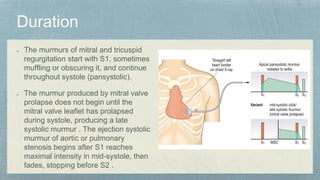

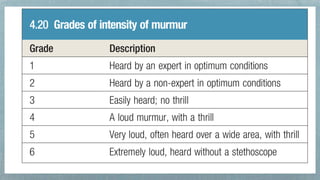

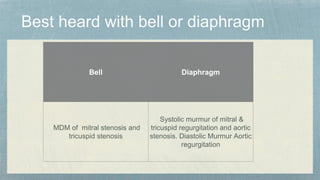

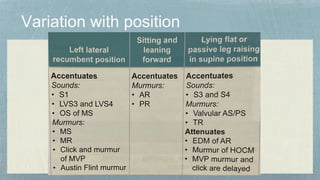

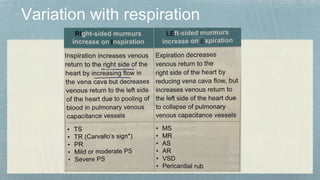

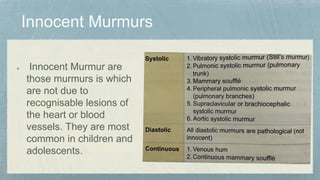

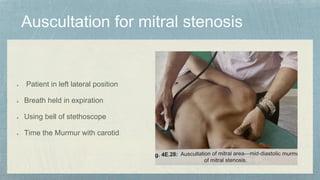

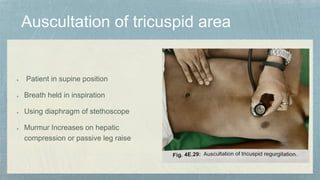

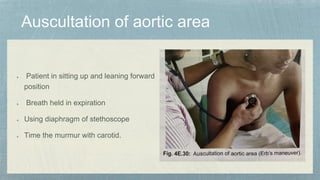

This document discusses techniques for percussion and auscultation of the heart. It describes how to determine the right and left heart borders through percussion. It then explains the sounds of the heart including the four heart sounds (S1, S2, S3, S4) and other sounds like clicks, snaps and murmurs. It provides details on the timing, location and characteristics of each heart sound and murmur and their associations with different cardiac pathologies.