This document is a project report submitted for an MSc in Business Systems Analysis and Design in 2011. It examines cloud-based business process management systems. Through a literature review and online survey, it aims to define cloud BPM and understand its applications and benefits from the perspective of BPM practitioners. Key findings include that cloud BPM provides scalability, flexibility and reduced costs compared to traditional BPM systems. The report contributes to understanding the emerging field of cloud BPM.

![2. LITERATURE SURVEY

there is BPM – the management discipline; on the other, there is BPM –

the technology, the means by which BPM is implemented in the organization

(Viaene et al., 2010).

It is clear that “cloud (computing)” denotes a type of technology, so when

“cloud”is combined with the term “BPM” to yield “Cloud BPM”, it is under-

stood that “BPM” in this case refers to the technology by way of which BPM

is implemented, and that the technology in question is cloud based.

Notwithstanding the particular case of the term “Cloud BPM”, whenever

the technology of BPM is intended (and not the discipline), the term “business

process management system” (BPMS) is commonly used, and that is the usage

that is employed in what follows here. The analysts Gartner have in the past

used the term “business process management technology” (BPMT) to refer

to the software element of BPM, but now generally use the term “business

process management suite” (BPMS), which implies a comprehensive BPM

software package that provides a standard range of functionality (modelling,

deployment, execution, etc.) (McCoy, 2011). For the purposes of this project,

these two meanings of “BPMS” – business process management system and

business process management suite – can be considered synonymous.

2.3 Business process management

BPM as a management discipline has its origins in previous management dis-

ciplines such as business process reengineering (BPR), as developed in the

seminal works of Hammer and Champy in the 1990s (Ko, 2009), and Total

Quality Management (TQM) (Viaene et al., 2010). Ko (2009) also cites Dav-

enport’s seminal contribution in emphasizing the crucial role of information

technology in the implementation of BPR in particular.

2.3.1 Defining BPM

In order to understand what BPM is, it is fitting to begin with an appre-

ciation of what is meant by a business process. Weske (2007, p5) defines a

business process as a set of activities that are performed in coordination in an

organizational and technical environment in order to realize a business goal.

According to Weske’s definition of the term, “each business process is enacted

by a single organization [emphasis added], but it may interact with business

processes performed by other organizations” (loc. cit.).

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-17-320.jpg)

![2. LITERATURE SURVEY

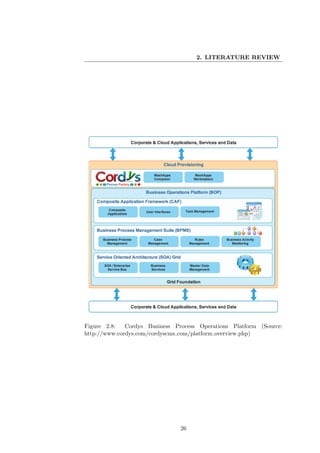

A BPMS can support the entire lifecycle of business process development –

discovery, modelling, execution, monitoring, optimization – from design-time

to run-time (Kemsley, 2011c) (see Figure 2.2 below). BPMSs provide a com-

position environment and process modelling tools to graphically reassemble

existing functionality outside the suite (usually in the form of services made

available through the implementation of a service oriented architecture) to

create a process application. A registry and repository are required to locate

What is a BPMS?

these reusable assets in the form of services (ibid.) (see 2.3.5).

Performance

Management

- Dashboards Integration

- Analytics adapters

- BAM Performance

Data Business

Systems

ERP

Integration

Framework

Process Design

CRM

Process Modeling

- Flow

- Flow - Resources Process EJB

- Resources/costs - Data Engine

- KPIs - Business rules

Business

Legacy

- Simulation analysis - Forms

Rules

- Integration

Business IT Human

User User User User workflow

Figure 2.2: Components of a BPMS (Silver, 2006)

According to Linthicum (2009, p129), the other components of a BPM

technology solution are:

• a business process engine that controls the execution of a process and

maintains the state of each of the process instances,

• a business process monitoring interface [performance management] for

the monitoring and optimization of processes,

• a business process engine interface that allows the other applications to

access the business process engine, and

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-20-320.jpg)

![2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.6 Summary

In this chapter, the literature surrounding the concept ‘Cloud BPM’ has been

reviewed.1 This began with a discussion of each of the two elements of the

Cloud–BPM marriage – cloud computing and business process management.

Thereafter, Cloud BPM, as it has developed since around 2006 until the

present, and as evidenced by the views of vendors, analysts and BPM practi-

tioners writing on the internet, was discussed. Certain themes have emerged,

and these will inform the tentative definition of Cloud BPM that is proposed,

and then tested, in the chapters following.

1

For the sake of completeness, one other manifestation of ‘Cloud BPM’ should be men-

tioned. Linthicum (2009, p127 ff.) discusses the relocation of “information, service and

processes [emphasis added]” to the cloud, rather than the relocation of a BPMS to the

cloud, and is therefore invoking the concept of ‘BPM-as-a-service’, mentioned above in Sec-

tion 2.4.1.

32](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-42-320.jpg)

![3. METHODS

such as a process repository or process marketplace were not included for fear

of including too many tick boxes, but an “Other” box was included to cater

for respondents who felt that other options were essential.

Q1.3 Cloud BPM is simply a delivery model for BPM tools - no

more, no less. (It’s not about WHAT you get, but HOW you get

it.) [Likert scale]

The final question in this section was intended to test the hypothesis that

Cloud BPM is no different from on-premise BPM, only the method of delivery

is different. The contrary of this would be that the nature of the cloud platform

for delivery of BPM solutions either (a) enhances or (b) detracts from the end

product, functionally of technically. Most of the respondents agreed with

the proposition that Cloud BPM is simply a model of delivery, having no

implications on the nature of the product in itself.

SECTION 2. The next section of the survey was headed “Characterizing

Cloud BPM” and was intended to tease out some of the issues that surround

cloud based BPM solutions.

Q2.1 Cloud BPM is a solution which is attractive mainly to the

SMB market. [Likert scale]

The first question of this section related to whether Cloud BPM was pre-

dominantly a solution that appealed to small and medium-sized businesses

rather than large enterprises. The hypothesis here is that many of the bene-

fits of cloud based BPM are related to the minimization of capital expenditure

and initial outlay required, lowering the barrier of entry to BPM solutions.

Q2.2 Cloud BPM is not suitable for the design and deployment

of complex business processes. [Likert scale]

The next question sought to gauge the respondents’ perception of the ca-

pabilities of cloud based BPM solutions by proposing that Cloud BPM is not

suitable for the deployment of complex business process. The implication is

that Cloud BPM solutions are more geared towards the creation of mashups,1

or the design and implementation of comparatively lightweight processes that

1

Web applications that combine data and/or functionality from more than one source

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mashup)

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-50-320.jpg)

![3. METHODS

can make use of existing templates and built-in connectors to the required

services.

Q2.3 New BPM initiatives pursued using a cloud BPM platform

will attract a lower level of business risk than the same project

pursued using traditional, on-premise methods. [Likert scale]

This question was meant to gauge the respondents’ perception of whether

cloud based BPM is better suited for developing new BPM initiatives eas-

ily, without requiring the mobilization of a large amount of IT department

resources in order to implement pilot projects, in other words, attracting a

lower level of business risk for the project.

Q2.4 Cloud BPM entails serious - and in some cases, prohibitive

- security risks. [Likert scale]

Question 2.4 sought to gauge respondents’ perception of the level of se-

curity risk associated with a cloud based BPM system. The question was

worded to find out if respondents felt that security risks were considered to

be of such a degree that they might seriously impact any decision to be made

about deploying BPM in the cloud.

Q2.5 One of the main advantages of Cloud BPM is its synergy

with ‘social’ BPM technologies. [Likert scale]

Question 2.5 sought to gauge respondents’ perception of the link between

cloud based BPM and social technologies that enable users to more easily col-

laborate in the design processes, as well as monitor processes that are running.

The hypothesis is that a cloud based BPM system is better suited architec-

turally for the provision of such functionality.

Q2.6 Due to its high strategic value to the organization, BPM is

not a suitable candidate for a cloud implementation. [Likert scale]

Question 2.6 aimed to test the hypothesis that since the business processes

that a company runs are of high strategic importance, due to the security con-

cerns associated with hosting the process information in a cloud environment,

a cloud environment is not suitable for the implementation of a BPM system.

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-51-320.jpg)

![3. METHODS

Q2.7 The full benefits of a cloud based BPM system will only

be realized when the application is purpose-built for deployment in

the cloud. [Likert scale]

Question 2.7 sought to gauge the respondents’ perception of the utility of

Cloud BPM towards introducing BPM initiatives easily and quickly, perhaps

on an experimental or pilot basis. The hypothesis here is that cloud based

BPM solutions can be introduced and trialled at a very low cost, without the

need to purchase new hardware or software, and without relying on the IT

department to mobilize for this change. In other words, Cloud BPM ban put

a BPM solution into the hands of the business users and allow them to pursue

pilot projects for a quick win, in order to demonstrate the efficacy of BPM

solutions in general.

Q2.8 The full benefits of a cloud based BPM system will only

be realized when an organization’s IT stack is predominantly cloud

based. [Likert scale]

Question 2.8 was intended to gauge respondents’ perception of whether

cloud based BPM was more suited to the management of business processes

when the rest of the IT stack was cloud based. The hypothesis here is that

cloud based BPM makes the most sense when the systems that it is interacting

with are architected specifically to operate in a cloud environment.

Q2.9 What are the main reasons for an organization to choose

a cloud based BPM solution over an on-premise solution? (Please

tick a maximum of FIVE reasons only.)

• quicker time to market

• lower start up costs

• reduced capital expenditure

• higher return on investment

• increased business agility

• elasticity of service

• reduced total cost of ownership

42](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-52-320.jpg)

![3. METHODS

• scalability of service

• better process collaboration

• Other

The last question in this section suggested some of the possible advantages

associated with cloud based BPM, and requests that the respondent choose

up to five main reasons. This question sought to identify the features of cloud

based BPM that respondents considered to be the most important.

SECTION 3. This section consisted of two open questions and was in-

tended to give respondents a chance to express their own views about Cloud

BPM’s advantages and disadvantages. It was expected that many respondents

would merely seek to emphasize certain points already covered in the survey

in previous questions, but it was hoped as well that some respondents might

provide new insights which the author had possibly missed. The questions

were worded as follows.

Q3.1 What are the main ADVANTAGES (business, functional,

technical, etc.) of a cloud based BPM solution? [Text box]

Q3.2 What are the main DISADVANTAGES (business, func-

tional, technical, etc.) of a cloud based BPM solution? [Text box]

SECTION 4. The final section of the survey was entitled ‘About you’ and

was intended to gather relevant personal data relating to the respondents, as

well as allow them to comment on the survey.

Q4.1 Which of the below best describes your primary role with

respect to with BPM?

• business analyst

• management level user of BPM methods and/or technologies

• end user of BPM technology

• software developer

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-53-320.jpg)

![3. METHODS

• researcher or academic

• researcher or academic

• student

• other

Q4.2 What is the size of your company by number employees?

• < 50

• 50–249

• 250–999

• 1000–4,999

• > 5,000

• n/a

Q4.3 Which sector does your company primarily operate in?

• oil and gas, mining, or agriculture

• manufacturing

• services

• IT services

• n/a

Q4.4 Please use the space below to provide any additional re-

marks about Cloud BPM and/or to comment on this survey. [Text

box]

The final question was intended to elicit comments from the respondents

about the form and content of the survey, but also to give respondents a chance

to bring to light any important issues that may have been omitted from the

survey.

44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-54-320.jpg)

![References

All, A. (2011). Companies showing interest in

cloud-based BPM. [Online]. URL http://www.

itbusinessedge.com/cm/community/features/interviews/blog/

companies-showing-interest-in-cloud-based-bpm/?cs=47722.

[11 July 2011]. 23

Appian Corp. (2011a). Appian BPM suite: SOA & integration.

[Online]. URL http://www.appian.com/bpm-software/bpm-components/

bpm-soa.jsp. [16 September 2010]. 23

Appian Corp. (2011b). BPM just got better. [Online]. URL http://www.

appian.com/bpm-resources/whitepapers.jsp. [16 September 2010]. 31

Appian Corp. (n.d.). Appian Cloud BPM. [Online]. URL http://www.

appian.com/bpm-software/cloudbpm.jsp. [01 July 2011]. 23

Armbrust, M., Fox, A., Griffith, R., Joseph, A., Katz, R., Konwinski, A., Lee,

G., Patterson, D., Rabkin, A., Stoica, I., et al. (2010). A view of cloud

computing. Communications of the ACM, 53(4), pp. 50–58. 20

Barlow, G.M. (2009). Business process management and cloud computing.

[Online]. URL http://www.bpminstitute.org/articles/article/

article/business-process-management-and-cloud-computing.html.

[14 July 2011]. 31, 69

BonitaSoft (2011). Bonita Open Solution, open source BPM.

[Online]. URL http://www.bonitasoft.com/products/

bonita-open-solution-open-source-bpm. [20 August 2011]. 23,

24

75](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-85-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

Byron, D. (2009a). BPM in the Cloud: One Plus One Is More Than

Two. [Online]. URL http://www.ebizq.net/topics/bpm/features/

11336.html. [25 June 2011]. 22

Byron, D. (2009b). Calling for Input on BPM in Cloud Computing: Let’s

Clear Away the Fog. [Online]. URL http://www.ebizq.net/blogs/

bpminaction/2009/04/calling_for_input_on_bpm_in_cl.php. [06 June

2011]. 30

Carr, N. (2003). IT doesn’t matter. Educause Review, 38, pp. 24–38. 69

Chorafas, D. (2010). Cloud computing strategies. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC

Press. 21

Chou, T. (2011). Be a student of cloud computing. [Online].

URL http://de.sap-spectrum.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/

SAP-Spectrum_2011-no02_E_lets_talk_business_timothy_chou.pdf.

[12 September 2011]. 70

Cordys B.V. (2011a). BPMS - Business Process Management Suite. [Online].

URL http://www.cordys.com/cordyscms_com/bpms.php. [17 Au-

gust 2011]. 21, 25, 70

Cordys B.V. (2011b). Enterprise Cloud Orchestration. [Online].

URL http://www.cordys.com/cordyscms_com/enterprise_cloud_

orchestration.php. [19 September 2011]. 27

Crusson, T. (2006). Business process management essentials. [Online]. URL

http://www.glintech.com/downloads/BPM%20Essentials%20with%

20Open%20Source.pdf. [01 August 2011]. 8, 13, 14

Datamonitor (2009). SaaS BPM: silencing the skeptics. [Online].

URL http://www.cordys.com/cordyscms_com/saas_bpm_datamonitor_

report.php. [23 May 2011]. 1, A-1

Dawson, C. (2009). Projects on computing and information systems: a stu-

dent’s guide. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education. 3, A-4

Deane, A. (2011). BPM: business users and programmers.

[Online]. URL http://adamdeane.wordpress.com/2011/08/09/

bpm-business-users-programmers/. [25 August 2011]. 14

76](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-86-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

Dubray, J.J. (2004). Business process modelling notation (BPMN). [Online].

URL http://www.ebpml.org/bpmn.htm. [23 August 2011]. 15

Dubray, J.J. (2007). The seven fallacies of business process execution. [Online].

URL http://www.infoq.com/articles/seven-fallacies-of-bpm.

[09 July 2011]. 14, 16

Dubray, J.J. (2008). Composite software construction. [Online]. URL http:

//www.infoq.com/minibooks/composite-software-construction.

[09 June 2011]. 22

ebizQ (2011). Is BPMN 2.0 being adopted by business? [Online].

URL http://www.ebizq.net/blogs/ebizq_forum/2011/03/

is-bpmn-20-being-adopted-by-business.php. [23 August 2011].

15

Ellahi, T., Hudzia, B., Li, H., Lidner, M., Robinson, P. (2011). The enterprise

cloud computing paradigm. In: R. Buyya, J. Broberg, A. Goscinski, eds.,

Cloud Computing: principles and paradigms, chap. 4. Wiley. 69

Gartner (2009). Gartner highlights five attributes of cloud computing. [Online].

URL http://www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?id=1035013. [15 Septem-

ber 2010]. 20

Gartner (2010). Hype cycle for cloud computing. [Online]. URL http://img2.

insight.com/graphics/se/general/gartner-122010.pdf. [13 Septem-

ber 2010]. 22, 29

Gartner (2011). Gartner survey shows 40 percent of respondents with BPM

initiatives use cloud computing to support at least 10 percent of BPM busi-

ness processes. [Online]. URL http://www.gartner.com/it/page.jsp?

id=1550514. [09 July 2011]. 16

Ghalimi, I. (2007). Who needs BPM as a service? [Online].

URL http://itredux.com/2007/02/23/who-needs-bpm-as-a-service/.

[06 July 2011]. 22

Gilbert, P. (2010). The next decade of BPM. [Online]. URL http://vimeo.

com/user4922460. [24 June 2011]. 11, 62

77](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-87-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

Han, Y., Sun, J., Wang, G., Li, H. (2010). A cloud-based BPM archi-

tecture with user-end distribution of non-compute-intensive activities and

sensitive data. [Online]. URL http://www.springerlink.com/index/

8606556182452001.pdf. 65

Hill, J., Sinur, J. (2010). Magic quadrant for business process management

suites. [Online]. URL http://www.gartner.com/DisplayDocument?doc_

cd=205212. [23 May 2011]. 9, 11

Hugos, M., Hulitzky, D. (2010). Business in the cloud: what every business

needs to know about cloud computing. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley. 6, 21

Intalio, Inc. (2011). Business process management. [Online]. URL http:

//www.intalio.com/bpm. [16 August 2011]. 27

Jost, W. (2011). Hidden in the cloud – the process platform for enterprise soft-

ware. URL http://soa.sys-con.com/node/1801463. [23 August 2011]. 9,

63, 65

Kemsley, S. (2011a). Forrester keynote at Appian World: realizing the

promise of BPM. [Online]. URL http://www.column2.com/2011/04/

forrester-keynote-at-appian-world-realizing-the-promise-of-bpm/.

[20 June 2011]. 30

Kemsley, S. (2011b). It’s not about BPM vs. ACM,

it’s about a spectrum of process functionality. Column

2. [Online]. URL http://www.column2.com/2011/03/

its-not-about-bpm-vs-acm-its-about-a-spectrum-of-process-functionality/.

[16 August 2011]. 12, 13

Kemsley, S. (2011c). Selecting a BPMS. [Online]. URL http://www.column2.

com/2011/04/selecting-a-bpms/. [23 August 2011]. 10, 12

Khan, R. (2006). BPM: a global view. [Online]. URL http://www.

bptrends.com/deliver_file.cfm?fileType=publication&fileName=

10-06-COL-BPMAGlobalView-Khan.pdf. [09 June 2011]. 22

Khoshafian, S. (2011). Ten technology trends in ten years.

[Online]. URL http://www.pega.com/community/pega-blog/

ten-technology-trends-in-ten-years-for-bpm-part-i-of-ii.

[01 August 2011]. 31

78](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-88-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

Ko, R. (2009). A computer scientist’s introductory guide to business pro-

cess management (BPM). Crossroads, 15(4). URL http://xrds.acm.org/

article.cfm?aid=1558901. [24 May 2010]. 7

Ko, R., Lee, S., Lee, E. (2009). Business process management (BPM) stan-

dards: a survey. Business Process Management Journal, 15(5), pp. 744–791.

8, 9, 14

Linthicum, D. (2009). Cloud computing and SOA convergence in your enter-

prise: a step-by-step guide. Boston: Addison-Wesley Professional. 10, 12,

19, 32

McCoy, D. (2011). A personal history of “BPM, the term”.

[Online]. URL http://blogs.gartner.com/dave_mccoy/2009/07/

06/a-personal-history-of-bpm/. [21 August 2011]. 7

Mitra, T. (2008). Architecture in practice, part 6: why busi-

ness process management (BPM) is important to an enterprise.

[Online]. URL http://www.ibm.com/developerworks/webservices/

library/ar-arprac6/index.html. [02 June 2011]. 69

NIST (2011). Cloud computing synopsis and recommendations. [Online].

URL http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/drafts/800-146/

Draft-NIST-SP800-146.pdf. [12 June 2011]. 17, 18

Ould, M. (2005). Business process management: a rigorous approach. Swin-

don: The British Computing Society. 1, 9, A-1

Palmer, N., Mooney, L. (2011). Building a business case for BPM – a fast path

to real results. [Online]. URL http://www.metastorm.com/solutions/

solution_sheets/Metastorm_Whitepaper_Building_A_Business_Case_

for_BPM_2009.pdf. [14 September 2011]. 9

Papazoglou, M. (2008). Web services: principles and technology. Addison-

Wesley. 13

Patig, S., Casanova-Brito, V., V¨geli, B. (2010). IT requirements of business

o

process management in practice – an empirical study. Business Process

Management, pp. 13–28. 14, 16

79](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-89-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

Pegasystems Inc. (2011a). Pega Business Process Cloud. [Online]. URL http:

//www.pega.com/solutions/cloud/business-process-management.

[14 September 2011]. 29

Pegasystems Inc. (2011b). Pegasystems announces cloud-enabled busi-

ness process management platform-as-a-service (PaaS). [Online].

URL http://www.pega.com/about-us/news-room/press-releases/

pegasystems-announces-cloud-enabled-business-process-management-pl.

[21 September 2011]. 29

Rosen, M. (2011). SOA and the cloud. [Online]. URL http://goo.gl/9zjwd.

19

Samarin, A. (2009). Improving enterprise business process management sys-

tems. Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford. 9

Silver, B. (2009). BPM and cloud computing. [Online]. URL http://www.

brsilver.com/bpm-and-cloud-computing-white-paper/. [11 Septem-

ber 2011]. 22, 68

Silver, B. (2006). What is a BPMS? [Online]. URL http:

//www.omg.org/news/meetings/ThinkTank/past-events/2006/

presentations/E-07_Silver.pdf. [06 July 2011]. 10, 14

Silver, B. (2007). Roundtripping revisited. [Online]. URL http://www.

brsilver.com/2007/11/28/roundtripping-revisited/. [06 July 2011].

15

Software AG (2011). CEBIT 2011 - Software AG announces next step in cloud

strategy. [Online]. URL http://www.softwareag.com/corporate/Press/

pressreleases/20110228_CeBIT_2011CloudComputing_page.asp.

[24 May 2010]. 29, 65, A-4

Spurway, K. (2011). The state of BPM: perspectives of an

industry insider. [Online]. URL http://www.bpm.com/

the-state-of-bpm-perspectives-of-an-industry-insider.html.

[09 June 2011]. 14

Tibco Software Inc. (2011). BPM in the cloud. [Online]. URL http://www.

tibco.com/products/bpm/bpm-cloud/default.jsp. [14 September 2011].

29

80](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-90-320.jpg)

![REFERENCES

van der Aalst, W., ter Hofstede, A., Weske, M. (2003). Business process

management: A survey. Business Process Management, pp. 1019–1019. 8

van der Aalst, W. (2004). Business process management demystified: a tutorial

on models, systems and standards for workflow management. Lectures on

Concurrency and Petri Nets, pp. 21–58. 8

Viaene, S., Van den Bergh, J., Schr¨der-Pander, F., Mertens, W. (2010).

o

BPM quo vadis. [Online]. URL https://lirias.kuleuven.be/bitstream/

123456789/270506/1/Vlerick_Quovadis_online.pdf. [13 June 2011]. 7

Wainewright, P. (2009). How does using a BPM solution in the cloud differ

from using an on-premise BPM application? Which is better? [Online].

URL http://goo.gl/ZVVRF. [24 May 2010]. 30, A-3

Wardley, S. (2009). Cloud computing – why it matters.

[Online]. URL http://www.slideshare.net/CloudCampFRA/

simon-wardley-cloud-computing-why-it-matters. [25 June 2011].

6, 16, 63

Weske, M. (2007). Business process management: concepts, languages, archi-

tecturres. Berlin: Springer. 7, 8, 13, 21, 70

81](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-91-320.jpg)

![References

Datamonitor (2009). SaaS BPM: silencing the skeptics. [Online]. URL

http://www.cordys.com/cordyscms com/saas bpm datamonitor report.php.

[23 May 2011].

Dawson, C. (2009). Projects on computing and information systems: a stu-

dents guide. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Ould, M. (2005). Business Process Management: a rigorous approach. Swin-

don: The British Computing Society.

Software AG (2011). Cebit 2011: Software AG announces next step in cloud

strategy. [Online] URL http://www.softwareag.com/corporate/Press/

pressreleases/20110223 CloudComputing page.asp [24 May 2011].

Wainewright, P. (2011). How does using a BPM solution in the cloud differ

from using an on-premise BPM application? Which is better? [Online]. URL

http://www.ebizq.net/blogs/ebizq forum/2009/03/

how-does-using-a-bpm-solution-in-the-cloud-differ-from-using

-an-on--premise-bpm-application-which-is.php [24 May 2010].

A-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-97-320.jpg)

![All of the groups require membership in order to post and generally consist of

discussions of BPM related topics. The post sent to each groups was worded

as follows.

screen capture Cloud BPM - a survey

Please spare a moment and bring your expertise to bear

on this short research survey.

Cloud BPM [link to survey]

Here is a screen capture of one of online posts:

Figure B.1: Post to LinkedIn BPM groups

B-2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-100-320.jpg)

![F. BPM Findings

Cloud is:

• a utility service [see Wardley]

• a delivery platform

Cloud entails specific security concerns:

• government access to data

• multi-tenancy

Cloud BPM may refer to:

• a BPM platform available as a service

• a BPM platform that supports the consumption of cloud services (cloud-

enabled BPM) (cf. Linthicum)

Cloud BPM is:

• also called on-demand, SaaS, cloud based, cloud-enabled

• attractive for first-timers, exploration

• attractive to the SMB market

• good for simple processes [define simple]

• sometimes SaaS

• sometimes PaaS

• sometimes talking about how to utilize external (public) services in pro-

cesses [NOT BPMS in the cloud]

F-1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-117-320.jpg)

![F. BPM FINDINGS

BPM is:

• a discipline, not a technology, involving

– process optimization

– human task management

– business transformation

– the business-side application of SOA

• a lifecycle [van der Aalst]

– design process (discover)

– (missing here, but important) simulation

– configure system (model)

– enact process (execute)

– diagnosis (analyse)

• an extension of “Workflow” (Wf + analysis)

• a quest for flexibility of business processes

– at an organizational level (design, discovery)

– at an operational level (runtime, workflows)

Processes are:

• a continuum of types [Kemsley]:

– structured

– structured with ad hoc exceptions

– adaptive with structured snippets (e.g. insurance claims)

– adaptive (e.g. innovation management)

• of different types, according to stage of activity lifecycle [Wardley]

– innovation

– bespoke

– product

F-2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-118-320.jpg)

![F. BPM FINDINGS

– commodity

Real Cloud BPM is:

• multi-tenant

• able to execute processes

• NOT just hosting

• allows round tripping - altering process alters model

BPM debates

• Are processes modelled in BPMN really executable?

• Is ACM part of BPM or not?

• Does cloud BPM provide any intrinsic advantages? [No]

• Is REST an adequate technology for BPM?

Questions:

• Is BPM a form of composite software construction?

• What are the prerequisites for BPMS to work? [SOA, middleware]

• How are the various databases linked?

• What is the actual architecture of the BPMS software [see Cordys doc-

umentation]

• How are MDD tools different from BPMS tools?

Miscellaneous

• In BPM there is no clear link between added functionality and cloud

architecture [despite Datamonitor claims]

• Perhaps the next logical step is a Cloud Platform [ala Cordys] where

BPM moves into Composite Application

– building for the cloud from the cloud

F-3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/railtonj-cloudenabledbpmsystems-bsad2011-120513122529-phpapp02/85/Cloud-enabled-business-process-management-systems-119-320.jpg)