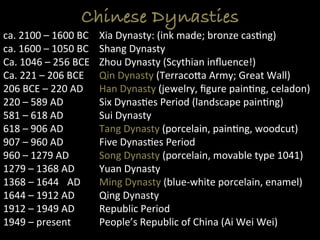

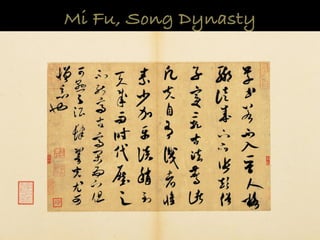

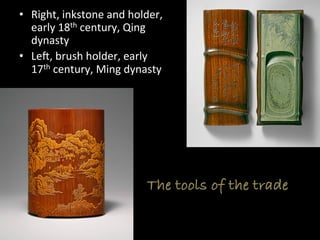

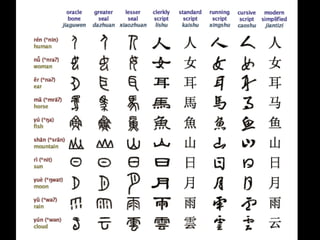

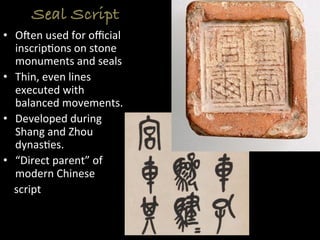

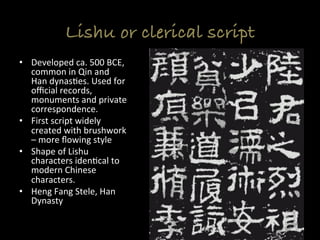

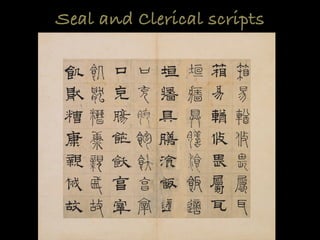

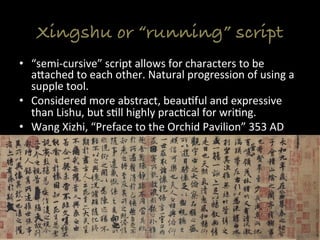

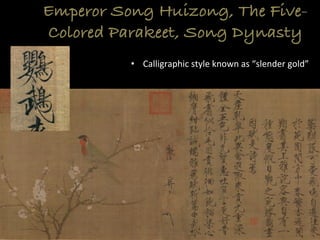

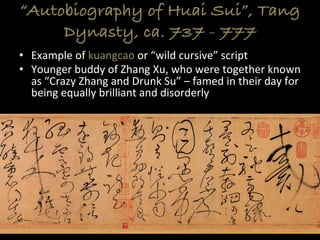

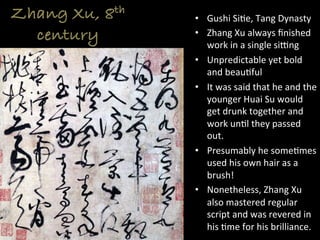

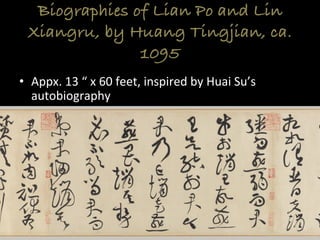

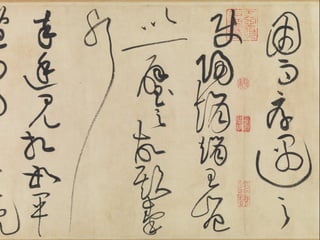

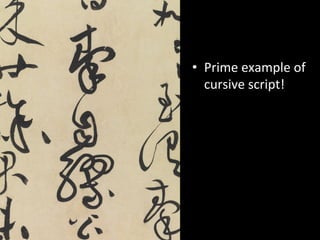

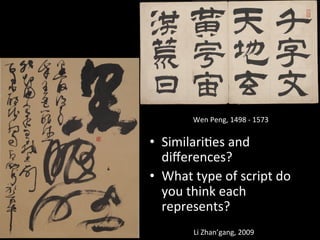

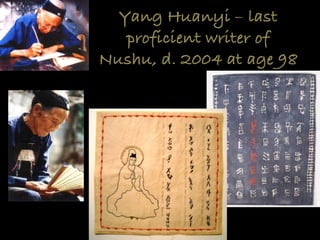

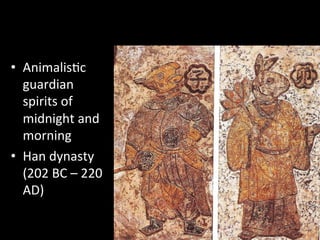

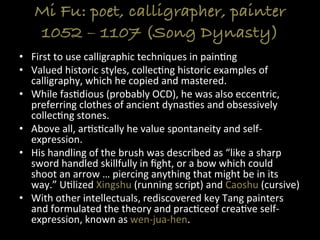

This document provides an overview of Chinese calligraphy and the development of written scripts in China from oracle bone style through various dynasties. It traces the evolution of Chinese characters from early pictographs to modern script styles like seal script, clerical script, standard script, running script, and grass script. The document also describes the traditional tools of calligraphy like brushes, inks, paper, and inkstones. It provides examples of famous calligraphers' works from different dynasties to illustrate the various script styles.