The document outlines the implementation of the OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974 standard for open-source software security by Endjin, a data consultancy. It highlights the importance of securing open-source software amidst its growing usage and the risks associated with vulnerabilities, emphasizing the need for compliance best practices. The project aims to develop autonomous processes that meet Endjin’s needs while adhering to the open-chain specification, ensuring that the software supply chain remains secure from known vulnerabilities.

![2 Introduction

As the world is quickly developing, the use of technology is growing more

so. This means large amounts of investment are being thrown at new

projects, and everyone is working as fast as they can to keep up with the

industry leaders. Technology is apparent in many different sectors: finance,

medicine, business, education, and so many more. As technology contin-

ues to advance, the demand for software grows, leading to an increasing

number of organisations creating and developing software. Open-source

software (OSS) defines free distribution and access to the source code

of software [1]. This software is released under different licenses, each

outlining its terms of usage; the most common types include permissive

and copyleft.

OSS is becoming more popular as it is cheap and easy to use, can easily

be integrated into developing software, and is constantly being updated.

However, many risks come with using OSS, which need to be taken into

account when using it, either personally or in an organisation. These risks

include both legal and security issues. Regardless of the project’s size,

whether it is a student’s dissertation or government top-secret documents,

any existing vulnerability in the code could potentially be exploited. While,

for hackers, targeting government information may be more ’beneficial’, no

software should be left untracked if the contents or data are important.

With OSS being very new, there are still standards, along with laws, being

developed, meaning new tools and processes are being created daily.

Every organisation will have different software that is written in different

languages and tackles different issues with different risks, so therefore, how

are we able to create tools that are general enough for everyone to use?

This is the issue companies are running into when trying to become safer

and more compliant using OSS. The software available that can manage

this is not always perfectly suited to their business. And so, this is where

the idea of my project stems: integrating processes for Endjin (discussed

later) that will ensure OSS safety.

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-10-2048.jpg)

![2 Introduction

2.1 Project aim

This project aims to aid in the implementation of the OpenChain ISO/IEC

18974 standard for Endjin, a data consulting company that specialises in

data engineering solutions. [2] They have a large range of open-source

software that assists both their work and the work of their customers.

The OpenChain project is a set of standards defined by the Linux Found-

ation that focus on the best practices for using and creating open-source

software. These standards aim to "reduce friction" and "increase efficiency"

when using open-source software [3]. There are two main standards they

maintain:

• OpenChain ISO/IEC 5230: The international standard for open

source license compliance programmes [4]

• OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974: The industry standard for open source

security assurance programmes [3]

As part of my degree, I completed a year in industry at Endjin. Over

the year, I implemented the OpenChain ISO/IEC 5230 standard, which

focuses on open-source license compliance. I defined and implemented

methods to create, track, and manage Endjin’s open-source software across

their code base. This included generating a software bill of materials

(SBOM, discussed later in the report). Endjin found this project as a whole

successful; they can now track all the licenses they are using across their

code base, instilling confidence that the software they are developing and

using is safe for both themselves and their customers to use.

As a result of this, Endjin was keen to get started on the second of the two

standards, OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974, and wanted a system that would

integrate well with their current work.

2.2 Objectives to Achieve Project Aim

The main objective of this project, as defined above, is to create software

for Endjin that helps them work towards achieving the OpenChain ISO/IEC

18974 standard.

The main stakeholder for this project is James Dawson [5], the Principle

Engineer at Endjin, who specialises as a DevOps consultant. He is in

charge of the DevOps processes across Endjin’s codebase and has a main

interest in the development of the specification. Ultimately, the biggest

priority for the project is to fulfil the specific requirements and desires of the

2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-11-2048.jpg)

![2 Introduction

stakeholders.

2.2.1 The OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974 Standard

This newly developed standard, focusing on security assurance, has been

developed since noticing OpenChain ISO/IEC 5230 being used in the

security domain [6], therefore deciding to create a standard based solely

on security. The specification [6] defines the ‘what’ and ‘why’ parts of

the programme, rather than the ‘how’ and the ‘when’. Instead of explicitly

defining what each organisation needs to do, they lay out the different

processes and documents that are needed because each case is unique.

The aim of this project is to target the implementation aspect of the spe-

cification rather than the policies and documents that Endjin would need to

generate. Consequently, only a segment of the specification relates to this

project:

• ‘It focuses on a narrow subset of primary concern: checking open-

source software against publicly known security vulnerabilities like

CVEs, GitHub/GitLab vulnerability reports, and so on’

• ‘A process shall exist for creating and maintaining a bill of materials

that includes each open source software component from which the

supplied software is comprised’

The above extracts from the specification set out the main objectives for

the project, checking all of Endjin’s software for publicly known security

vulnerabilities.

2.3 Why Open-Source Software Security is

Important

Although OSS is cheap and easy to use, it comes with a number of risks that

organisations or users need to be aware of in order to use the code safely.

OSS can be found everywhere [7], making up over 80% of the software

code in use in modern applications. Whole applications themselves can

be open-source, such as the Android operating system for mobiles, which

is used by over 3.3 billion people[8]. Even though this system itself is

just one piece of open-source software, it could potentially use hundreds

or thousands of different OSS libraries and packages. These packages

could use more OSS licenses and packages; this is a demonstration of the

software supply chain.

3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-12-2048.jpg)

![2 Introduction

The term ‘software supply chain’ refers to the representation of depend-

encies that exist within a software component. While that programme will

have code of its own, it is likely that it also uses open-source software to

build up certain components. These components could also have OSS

dependencies, therefore creating this idea of a software supply chain, which

commonly appears as a tree shape.

The log4j attack is one of the most well-known vulnerabilities across the

world. Log4j is a Java logging framework that is listed as one of the top

100 critical open source software projects [9] and is used commonly across

software and website applications. The vulnerability, which was discovered

in 2021, was easy to exploit, requiring very little expertise [10]. Because it

is such a widely used piece of software, many organisations were unaware

that this software was being used in their supply chain. A patch was

released very quickly, allowing users to update their software; however, it

was discovered that even two years after the attack, 2.8% of applications

were still using the un-patched version of Log4j [11]. In a study [11] it was

found that 79% of the time, developers didn’t update the dependencies they

were using after they added them to the software, which is apparent when

it is estimated that a third of applications currently are using a vulnerable

version of Log4j.

There are several companies that have already completed the OpenChain

ISO/IEC 18974 standard. Blackberry was the first in America, [12], and is

focused on ‘building a more resilient and trusted software supply chain’.

2.4 Approach to the project

Initially, when starting this project, I intended to develop a tool that Endjin

could use that would scan a representation of their code base for any

vulnerabilities and give a report based on its findings. However, after re-

searching the current state-of-the-art, I came across many already existing

tools that did exactly what I had planned, if not more so. Although the pro-

cess of building this tool from the ground up could have been a fascinating

experience in data gathering and manipulation, it doesn’t align with the

project’s best interests. There are better solutions out there, and some are

open-source too.

This changed my approach. Having intended to initially develop a singular

tool, I now decided to develop an autonomous process for Endjin that would

run and ingest the results of a vulnerability scanner built up from Endjin’s

current architecture (discussed in more detail in the background section).

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-13-2048.jpg)

![3 Background

3.1 SBOMs

A Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) serves as an inventory of all compon-

ents and dependencies within a given software. It defines all the parts

that make up the specified application. As SBOMs have become more

popular in the open-source community, there have been more standards

and formats emerging, so implementing and standardising these security

standards will be much easier. The two main leading SBOM formats are

SPDX and CycloneDx.

Endjin uses a tool called Covenant [13] made by Patrik Svensson. SPDX

SBOMs can be generated with a custom alteration that includes some

extra meta data. By integrating this tool into Endjin’s build processes, an

updated version is automatically produced each night and uploaded to their

database. Once there, the information undergoes a cleansing process,

preparing it for analysis in accordance with the OpenChain ISO/IEC 5230

procedures.

SBOMs can be used for each piece of software to track components and

dependencies; these files can be analysed and checked to gain insight into

a system as a whole.

3.2 Vulnerability Databases

Once vulnerabilities are identified, they are recorded and published in a

vulnerability database, alerting users to known software issues. One of

the most prominent databases is the [14] National Vulnerability Database,

which includes security-related software flaws, product names, and impact

metrics, aiding in automated vulnerability detection.

The database includes Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs)

which are, as referenced to by NIST [15], a dictionary of vulnerabilities.

They are assigned an ID so they can be easily searched for and identified.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-14-2048.jpg)

![3 Background

Once the CVEs have been defined the NVD [14], which is managed by

NIST, will analyse each entry and upload it to the NVD.

GitHub’s Advisory Database, which includes CVEs and advisories from

open-source software, integrates well with GitHub’s automatic scanner

and adviser. However, it may not be as effective for Endjin as not all their

software is hosted on GitHub.

While vulnerability databases are useful, they also alert potential hackers to

known vulnerabilities, highlighting the need for automated processes that

scan for vulnerabilities and update software promptly.

3.3 Vulnerability Scanners

By producing SBOMs for software, it’s possible to accurately represent an

entire codebase as a list of distinct elements. This is only the beginning

of what is required for security compliance, as these components need

to be checked against real vulnerability data. As discussed above, this

information can be collected from vulnerability databases. A large number

of these databases feature APIs that facilitate the downloading or querying

of their contents. Existing state-of-the-art open-source tools can perform

this exact function, often with additional features.

Certain vulnerability scanners rely on a single database, which could lead

to a single point of failure. This could result in overlooking a vulnerability

that another database might have detected. Therefore, it’s crucial to select

a scanner that gathers data from a reliable source to avoid missing any

potential vulnerabilities. The size of the system should also be a considera-

tion when selecting a tool, as some scanners may not have the capability

to handle larger systems and could operate too slowly.

The tools ‘Grype’ [16] and ‘Syft’ [17] are examples of products created by

Anchore Inc. [18] Syft is a CLI tool and library that generates an SBOM from

container images and filesystems. Endjin’s predominantly used language

is C#, which isn’t supported by Syft. Anchore’s other product, Grype, can

take a range of different SBOMs and scan them for vulnerabilities, checking

the results against an external database. This could cover the vulnerability

scanning section of my project.

Another tool I found to scan vulnerabilities is called ’Bomber’ [19], an open-

source repository that takes either SPDX [20], CycloneDx, or Syft [17]

SBOM formats. It uses multiple different vulnerability information providers:

OSV [21], Sonatype OSS index [22], and Snyk [23]. You have to pay for

Snyk, while with Sonatype you register for free, and OSV is fully free.

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-15-2048.jpg)

![3 Background

Docker Scout [24], a built-in feature of Docker, automatically scans con-

tainer images for packages with vulnerabilities. It displays an assigned

CVE, providing details like the vulnerability’s severity and the error’s version

number.

There are several vulnerability scanners that, for this project, aren’t con-

sidered given they are not open-source software; these included FOSSA’s

vulnerability scanner [25] and Vigilant Ops [26], which have tools that create

and scan SBOMs.

3.4 DevOps processes

As it evolved, what was initially conceived as a software development

project has morphed into a DevOps initiative. The primary objective is now

to aid Endjin in enhancing their DevOps workflows.

DevOps is a methodology that encourages communication, automation,

integration, and rapid feedback cycles[27]. A DevOps platform brings

together lots of different tools and processes into one system that can be

maintained[27]. It is built on top of the principles of Agile development,

which focus on incremental and iterative processes[27].

Continuous Integration (CI) and Continuous Development (CD), also known

as CI/CD, play a key part in following and developing DevOps processes.

CI/CD are the processes that automate code management, from running

automated tests to deploying and building the software[28].

This project will support Endjin’s CI/CD processes, which will involve check-

ing software for vulnerabilities. This can be for the codebase as a whole,

or the system developed can be used on individual repositories which can

be checked before being merged into the main branch of code. In terms of

DevOps, this is an autonomous process that can integrate with the rest of

Endjin’s DevOps platform, meaning it will be tied in with the rest of Endjin’s

software.

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-16-2048.jpg)

![4 Methodology

To design and evalutate the project, I will use a range of different methodo-

logies which will help to achieve the project’s objectives. For each, I justify

any variations in methods I have made to better suit this project and each

method is supported by the appropriate literature.

The first, Requirements Engineering ensures that the stakeholders of the

project get the system that they need and that based on their requirements

the appropriate strategy is taken.

AGILE

4.1 Requirements Engineering

Requirements Engineering is the process of identifying, analysing, spe-

cifying, and managing the needs and expectations of the stakeholders to

implement a software system effectively[29].

The five Requirement Engineering processes to be applied include con-

ducting a feasibility study, eliciting and specifying requirements, verifying

and validating these requirements for accuracy and stakeholder alignment,

and managing these requirements through documentation, tracking, and

stakeholder communication throughout the development lifecycle.

Somerville’s ‘Software Engineering’ book [30] outlines four unique stages

of the Requirements Engineering process. The second process, ‘Require-

ments elicitation and analysis’, talks through two processes about collecting

and deciding on requirements. In the context of my project, where there

is a focus on understanding the requirements from different sources, I

have decided to look at both the elicitation and analysis separately. This

will allow me to more clearly distinguish between the two and therefore

better understand the requirements. I will name the ‘requirements analysis’

section ‘requirements specification’ instead because it better encompasses

both the analysis of requirements and the formalisation of them.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-17-2048.jpg)

![4 Methodology

4.1.2 Requirements Elicitation

Requirements Elicitation is the stage of the process that collects information

regarding the requirements of the system. There are usually a range of

different methods of identifying these, such as surveys, focus groups, and

prototyping. For this project, I will be conducting interviews with Endjin

to understand the current state of their system and the features they are

expecting. As this software is being used in a system for a company that is

currently operating in the industry, their business needs and expectations

for the project must be properly accounted for.

In these interviews with James Dawson [5], the main stakeholder for this

project, I discussed the current state of their DevOps architecture and

learned how their different components currently interact with one another.

This was crucial to learn so I could tailor my solution to be as similar to their

current system as possible and achieve a seamless transition from one to

the other. He outlined a few different requirements and expectations:

• Understanding the size of the vulnerability: Given a vulnerability, what

is its severity, and how quickly or urgently should it be fixed and

looked at?

• How big of an impact is an update? Is it just a minor update, or

will it be a major update that could potentially break current code if

updated?

• Be able to view the current state of each component and whether

there are any vulnerabilities on a site they can easily access.

• Be notified of any vulnerabilities that require a serious change or

could break code if updated.

Because Endjin both develops its own open-source software and uses third-

party dependencies, it is a priority to them that they have the assurance

that their code isn’t vulnerable. This is especially important because Endjin

are consultants, meaning they develop solutions for companies and provide

help to them on specialist subjects. A lot of this involves open-source

software and developing solutions for customers using their own OSS and

freely available OSS.

One of their requirements was that I be led by the OpenChain specific-

ation to make my decisions. Understanding and applying the guidance

from the specification to Endjin would be the most important. Given that

ISO/IEC 18974 primarily serves as a prescriptive standard, there are very

generic aims and goals that can be interpreted differently depending on the

organisation.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-19-2048.jpg)

![4 Methodology

Understanding the requirements of the OpenChain 18974

Specification

The OpenChain specification [6] encompasses several aspects, including

awareness and policy. These elements identify who is accountable for

implementing changes and ensuring no vulnerabilities exist. It also involves

training staff members to keep them informed about what changes have

been made, the reasons behind these changes, and any actions they

may need to take to maintain the company’s compliance. While these

are extremely important to become compliant and to be assured that they

are as safe as possible, the main focus will instead be on the high-level

requirements set out by James Dawson mentioned above. This is because

the remaining parts of the specification are primarily for the company’s

discretion, while this project’s focus is on the implementation aspect.

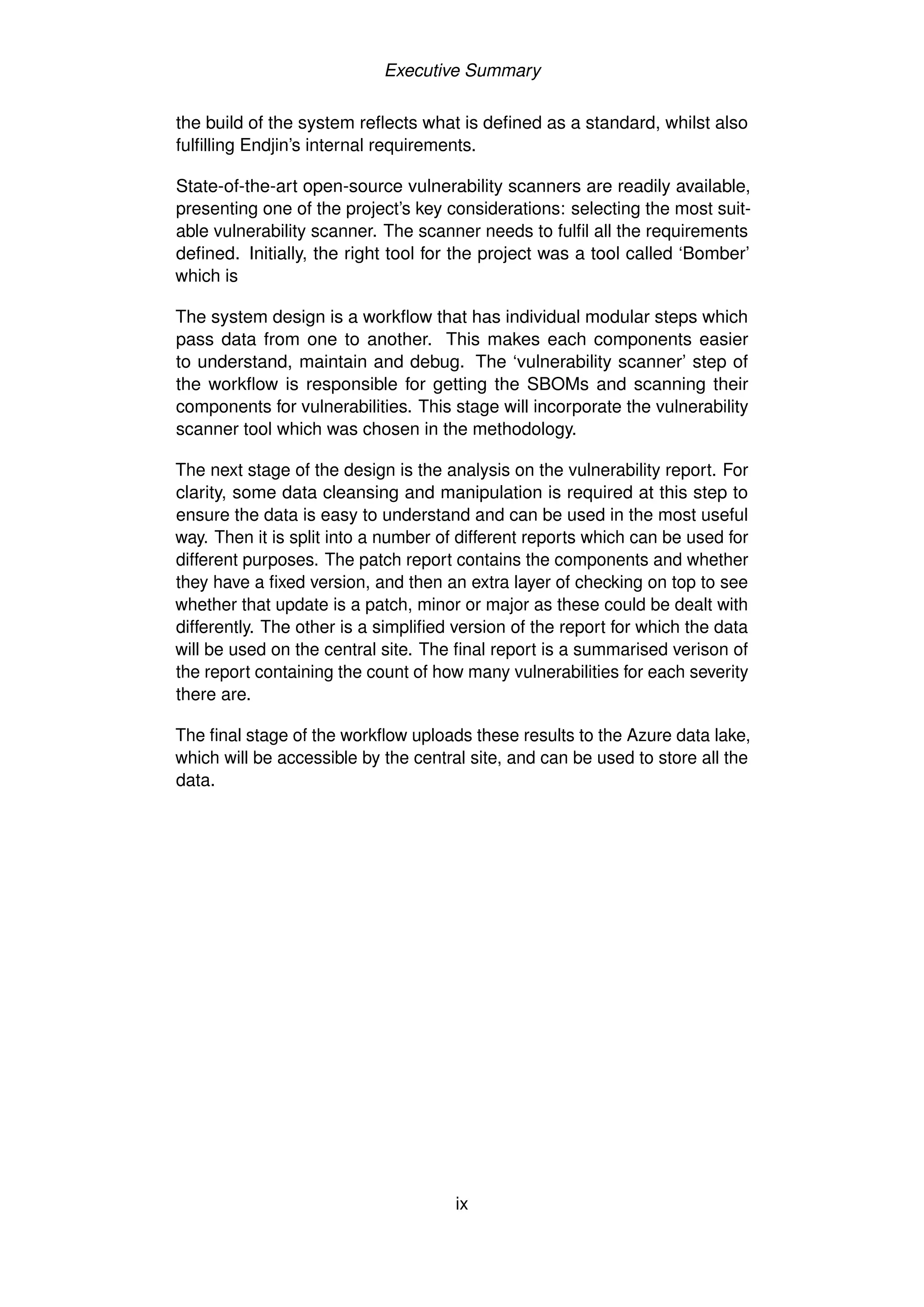

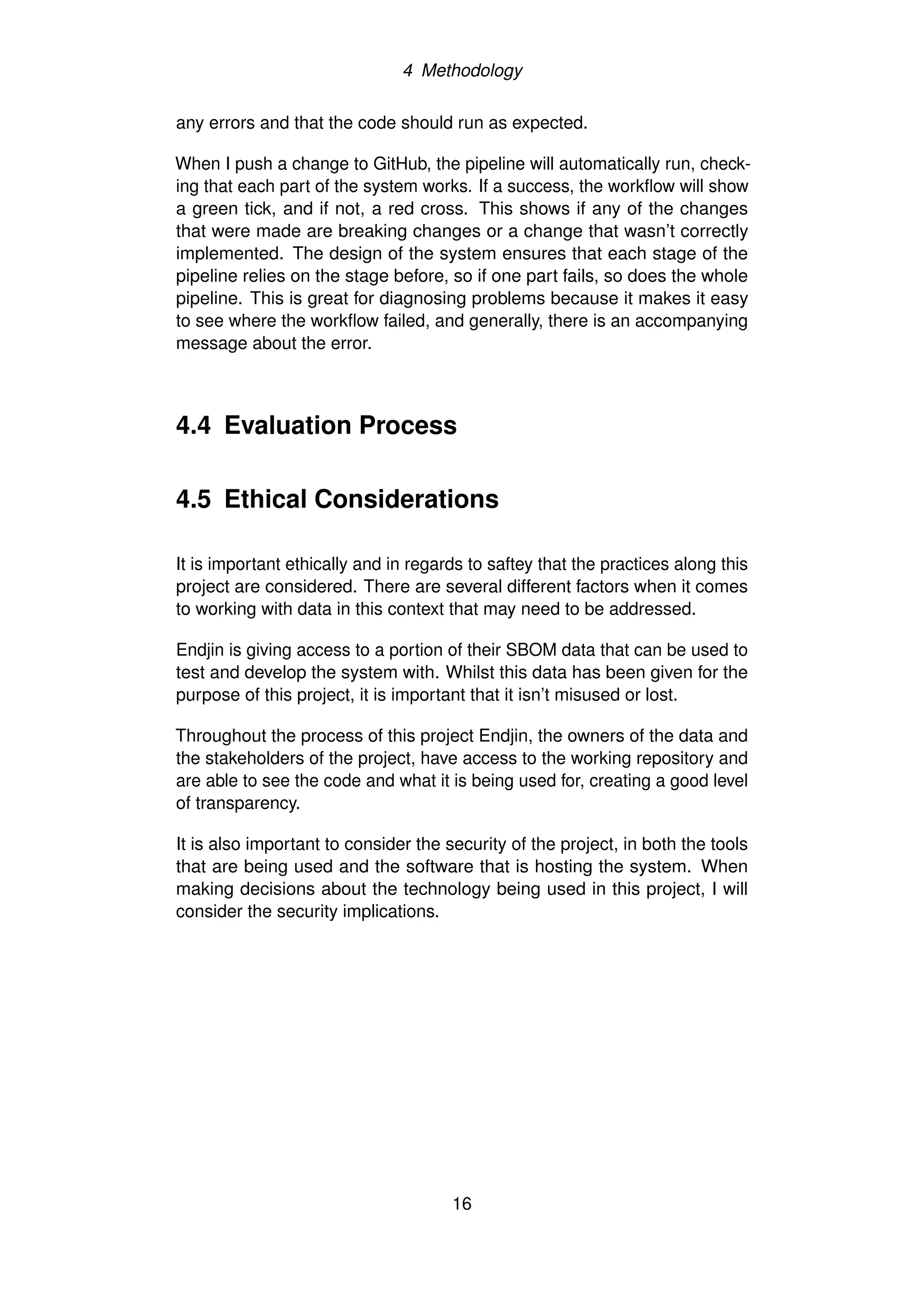

Table 4.2 shows the main implementation practices available to Endjin. The

requirements defined by OpenChain for the security assurance specification

are listed under the ‘Requirement’ column. The second column contains

the decision on whether to cover the implementation as part of the project.

Table 4.2: Table showing the requirements of the OpenChain specification

with the decision I made on whether to implement each one

Requirement Decision

Method to identify structural and technical threats to the supplied

software;

No

Method for detecting the existence of known vulnerabilities in

supplied software;

Yes

Method for following up on identified known vulnerabilities; Yes

Method to communicate identified known vulnerabilities to the cus-

tomer base when warranted;

No

Method for analysing supplied software for newly published known

vulnerabilities post-release of the supplied software;

No

Method for continuous and repeated security testing to be ap-

plied for all supplied software before release;

Yes

Methods to verify that identified risks will have been addressed before

the release of supplied software;

No

Method to export information about identified risks to third

parties as appropriate.

Yes

Internally, Endjin will need to make extra decisions regarding the require-

ments, which would be beyond the scope of this project due to developing

this system externally for Endjin. While these requirements cannot fully be

implemented in the design of the system, the foundation can be created to

support Endjin’s further development.

The requirements that discuss identifying risks before and after supplied

software is released can be partially implemented in this system because

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-20-2048.jpg)

![4 Methodology

there will be the functionality to scan software for vulnerabilities; however, it

will require some extra steps along with this implementation from Endjin to

fully meet these requirements. Similarly to the requirement, which defines

a method to communicate vulnerabilities to the customer base, whilst this

system itself won’t communicate these changes, it can still create a report

that can be sent to customers. The responsibility, however, to send these

to the customers will be of Endjin.

The requirements appropriate and in scope for this project include creating

methods for detecting the existence of known vulnerabilities and displaying

this information in a useful way. This includes having a method that will

allow for continuous integration and testing. Finally, to have a method to

generate a report that Endjin can send to appropriate third parties.

4.1.3 Requirements Specification

Requirements specification is the process of formalising the data collected

in Requirements Elicitation. It encompasses the analysis stage to prioritise

and structure requirements into easy-to-manage tables. These will describe

the expected functionalities of the system and set expectations for how they

are run, grouped by functional and non-functional requirements.

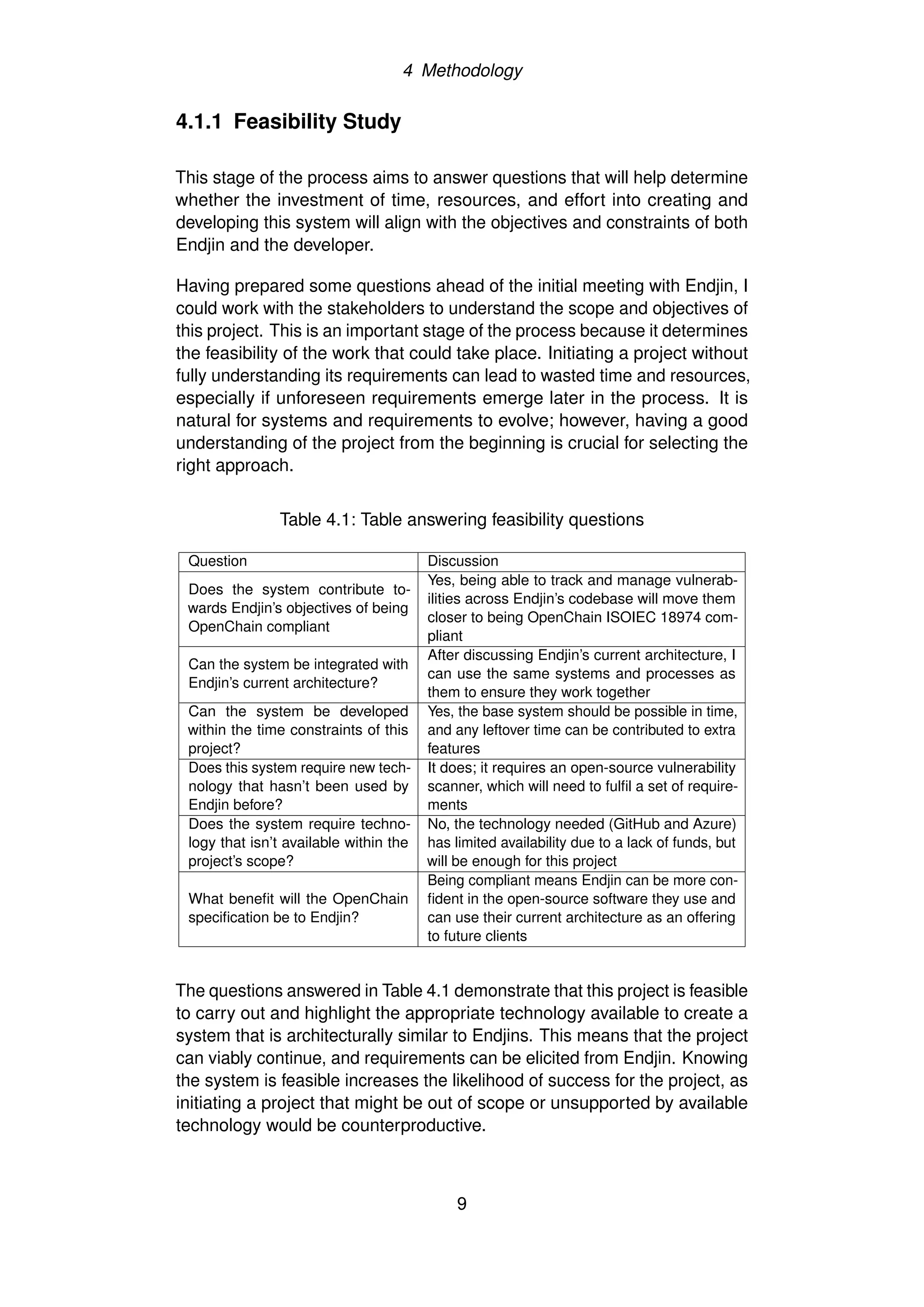

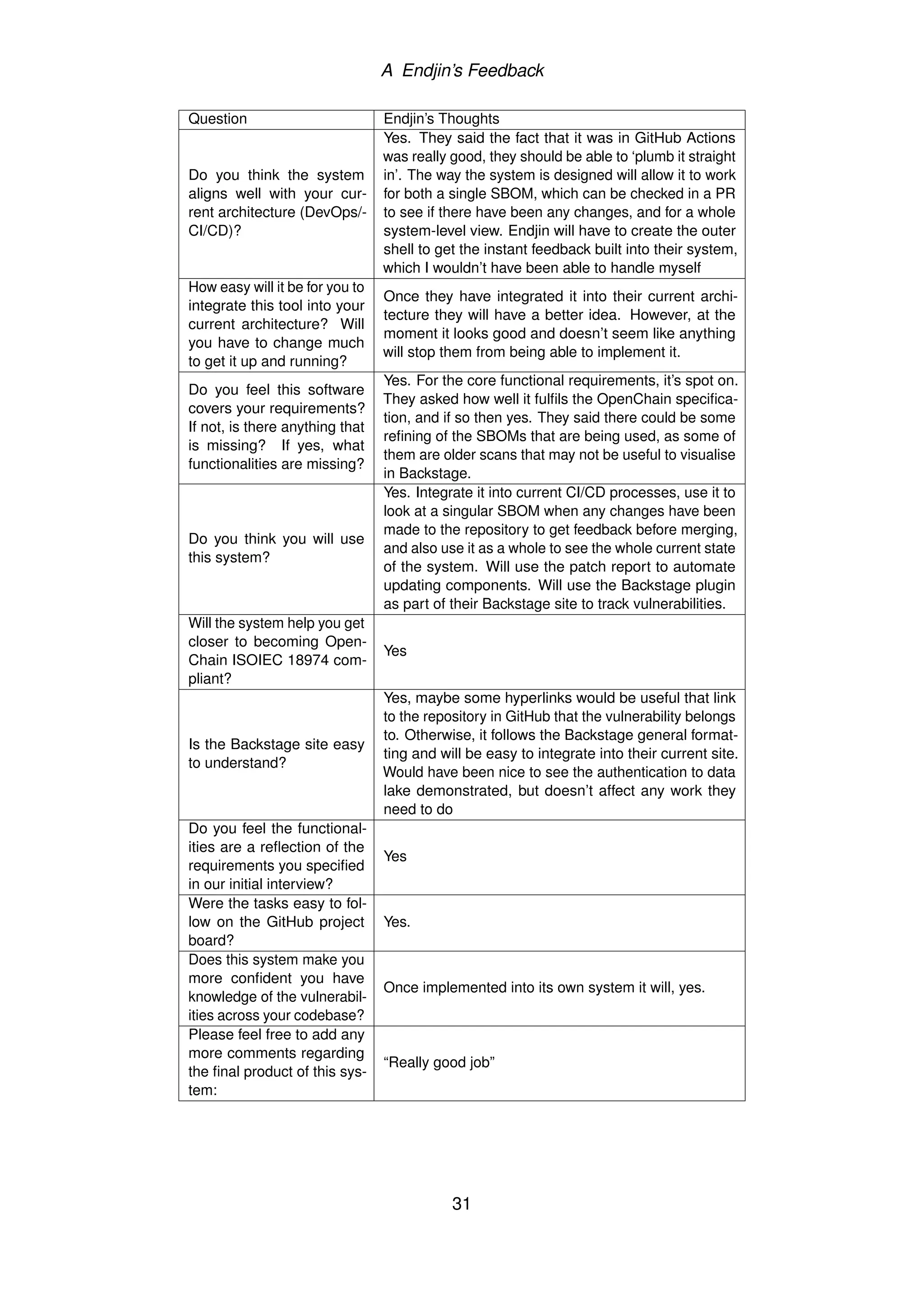

Firstly, the functional requirements (Table 4.3), which define how the system

must work [31]. This includes all the functionalities defined by Endjin and

the OpenChain specification, which together will guide and shape the

project.

Table 4.3: Table showing the functional requirements

No. Requirement

1 Collect SBOMs from the cloud;

2 Convert SBOMs to the correct format;

3 Scan each SBOM for vulnerabilities;

4 Store vulnerability data;

5 Cleanse vulnerability data to improve clarity;

6 Generate a report with patch number recommendations;

7 List update types in patch recommendations e.g. patch, minor, major;

8 Display data on a central site;

9 Assign severity scores to identified vulnerabilities;

10 Include version number and patch recommendations for vulnerabilities identified;

11 Identify the source SBOM for each vulnerability;

12 Store vulnerability reports in the cloud;

13 Automatically run the system upon code changes;

14 Users can sort data from ascending to descending severity on the output site;

15 Seamlessly integrate with Endjin’s CI/CD pipelines;

16 Able to scale for varying numbers of SBOMs;

17 Keep vulnerability data private;

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-21-2048.jpg)

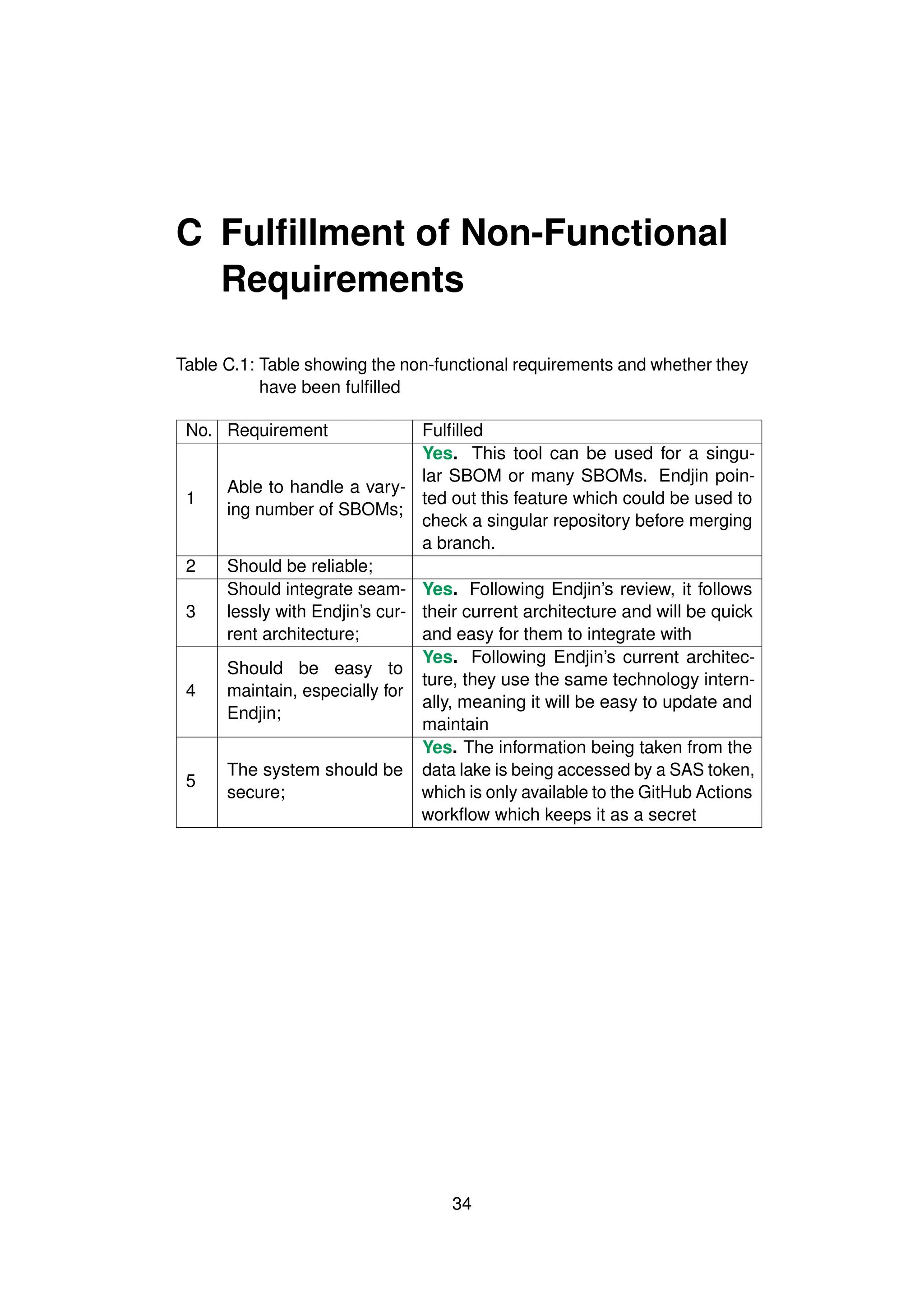

![4 Methodology

The success of the project is not only determined by meeting Endjin’s

requirements but also by ensuring easy integration into their current code-

base, with the overarching goal of minimising additional work for Endjin.

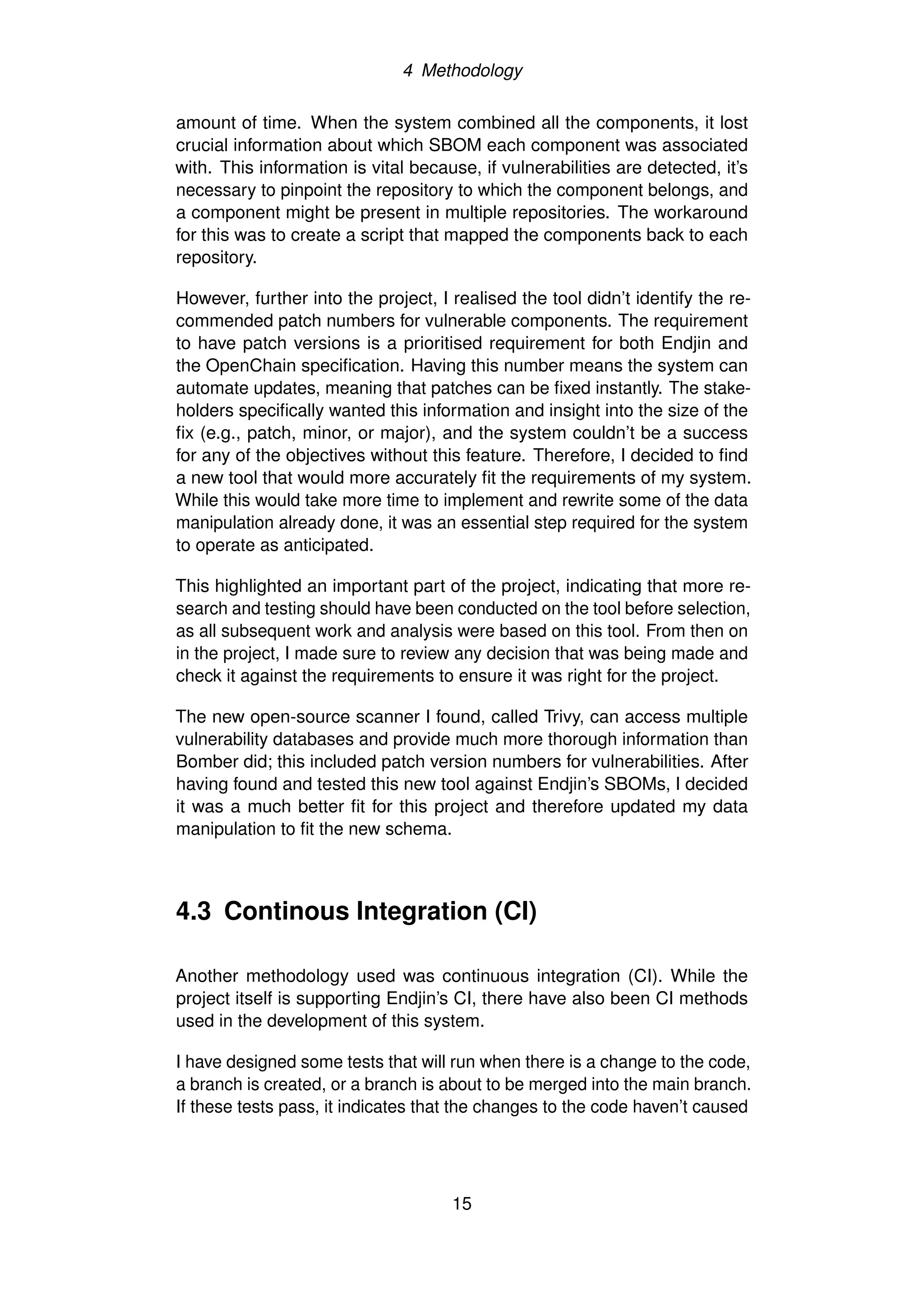

The non-functional requirements (Table 4.4) describe how the system

works; they don’t affect the functionality of the system; however, they are

focused on the system’s usability and robustness.

Table 4.4: Table showing the non-functional requirements

No. Requirement

1 Able to handle a varying number of SBOMs;

2 Should be reliable;

3 Should integrate seamlessly with Endjin’s current architecture;

4 Should be easy to maintain, especially for Endjin;

5 The system should be secure;

4.1.4 Requirements Verification and Validation

This stage of the Requirement Engineering process is where the require-

ments are reviewed and checked so that, together, they support the stake-

holder’s overall understanding of the system and the communicated re-

quirements. This process validates the specified requirements, ensuring

no functionalities are overlooked. The completion of these indicates the

system’s coverage and readiness. To verify the requirements, it must be

considered whether they are completable within the scope of the project

and to ensure that the requirements don’t collide with one another [29].

To validate the requirements, I engaged with the stakeholders to review both

the functional and non-functional requirements derived from the interviews.

This ensured we were all aligned with our understanding of the system’s

expected functionalities.

To verify the requirements were suitable for the system as a whole, I re-

viewed the requirements to ensure there were no inconsistencies and that

they were testable so that during implementation they could be demon-

strated to prove that the functionality exists and works.

I reviewed and conducted this step of the Requirements Engineering

method multiple times during the process of my project to ensure the

requirements were still relevant. Further along in the project, when there

is more knowledge about the system as a whole, it could change the

perspective on these requirements, highlighting some that may not be

possible or could have conflicts. Additionally, I checked in with the stake-

holders regularly to discuss the progress of the project and to ensure these

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-22-2048.jpg)

![4 Methodology

requirements were still a reflection of their expectations.

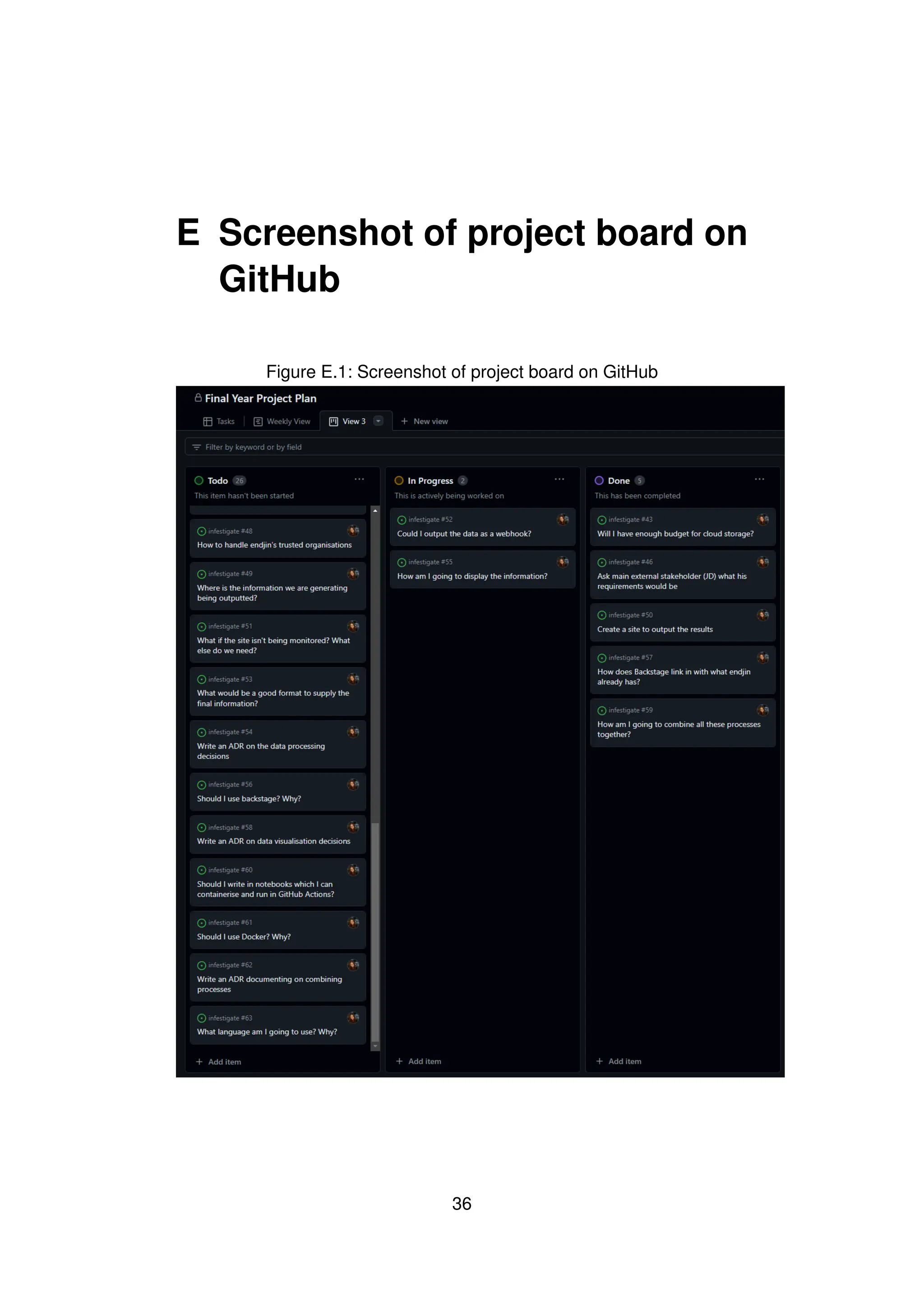

4.1.5 Requirements Management

Requirements Management is an important part of Requirements Engin-

eering to track the changes that could occur. The requirements that are

designed are crucial to the development and success of the project, so hav-

ing a versioned history of these helps to keep track of what was completed,

and what still needs to be done.

I utilised GitHub Projects [32] within my repository to monitor the progress

of my implementation. Projects are made up of ‘issues’ and ‘pull requests’

which can be categorised on a visual board. I used the columns ‘To-

Do’, ‘In Progress’, and ‘Done’. Each issue was a card on the board that

represented a task that needed to be done. Some of the requirements were

better broken down into smaller tasks, which made it easier to measure

the progress when working toward a specific requirement. For each of the

tasks I assigned a ‘Task Size’ to label how big the task was, and therefore

how long it might take to complete.

This management board was useful during the process of the development

of the system. Being a singular person working on this project, it was useful

to be able to track my progress, both for Endjin and myself, because they

can see what features are currently in progress and how the project is

coming along.

4.2 Picking a Vulnerability Tool

When researching an appropriate tool for my system, it needed to fulfil

all the requirements of my system. This includes being able to scan an

SPDX-format SBOM for components and using vulnerability data from an

external database to check these for any security threats. The tool would

also have to identify what the threat is and, if there is a patch, communicate

this information.

Initially, the first tool I came across, as discussed in my background section,

was Bomber, the vulnerability scanner. There were a few different issues

with this tool. Initially, the tool scanned a folder full of various SBOMs. To

save time, it extracted all components from the SBOMs, removed duplicates,

and then queried each unique component against a database. Despite this

efficiency, the workflow, as discussed later, still consumed a considerable

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-23-2048.jpg)

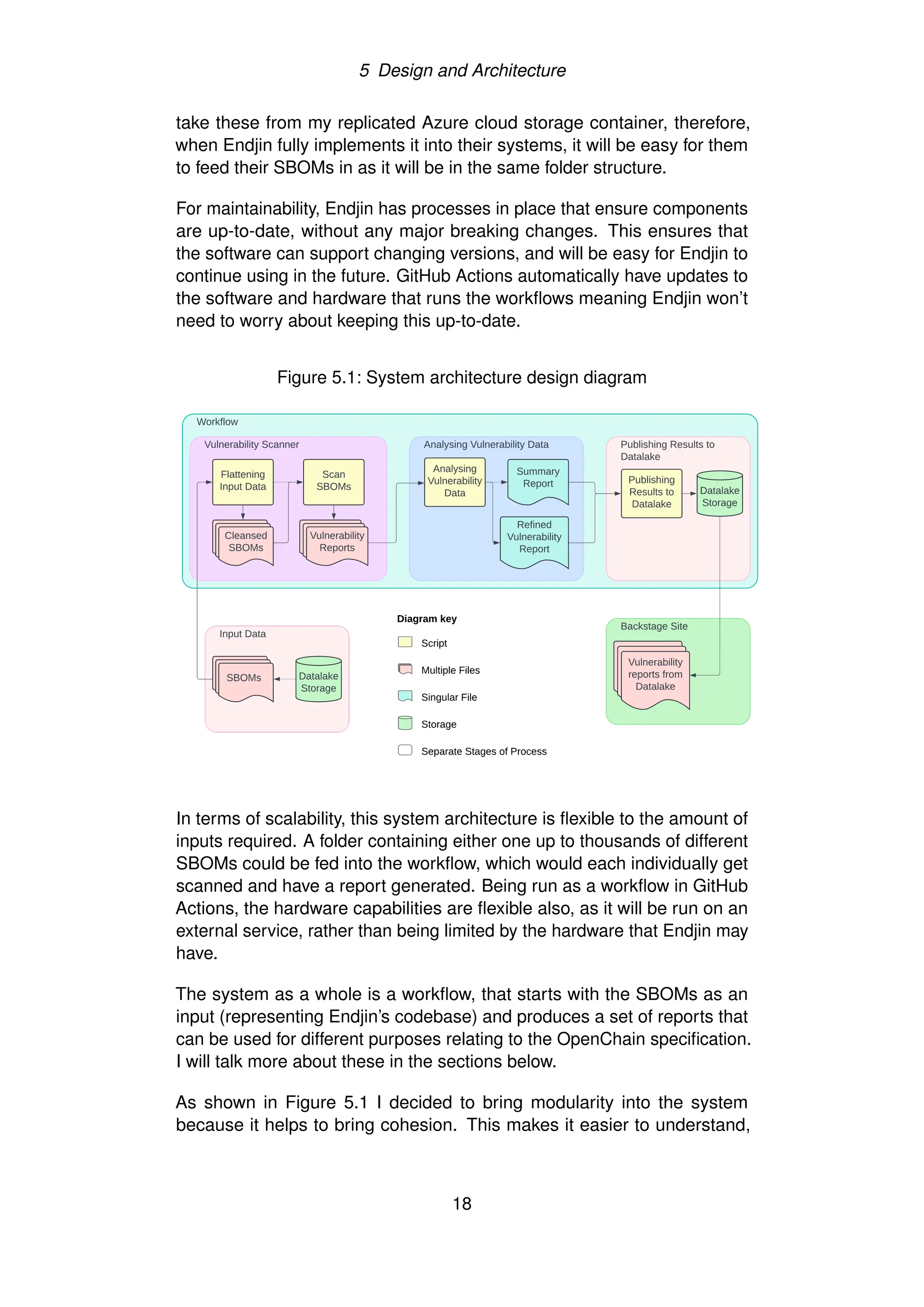

![5 Design and Architecture

DevOps processes to automatically update their components with the right

version numbers.

5.4 Publishing Results to Datalake

Once all the reports have been generated from the ‘Analysing Vulnerability

Data’ stage, these need to be stored somewhere that the information can

be accessed and used. Endjin’s current architecture heavily uses the Azure

storage data lake to store lots of their data. This includes their SBOM

data and the analysed results. Therefore, to follow Endjin’s architecture as

closely as possible, meaning more of a seamless transition for them to add

this tool to their system, the output data will be stored in the cloud.

Aligning with Endjin’s current architecture isn’t the only benefit of saving

the data to the cloud, it also enables the central site (as defined in the func-

tional requirements) to access this information more easily. The site is an

important part of the project, which displays the results of the vulnerability

data so that Endjin can see the current state of its codebase concerning

safety.

5.5 Designing the Backstage Site

Whilst the central site (as defined in the requirements) isn’t the main focus

of the project, it is important to demonstrate how the data can be visualised.

The value of the data can be assessed when correctly displayed because

it is an important step in understanding the vulnerabilities in the system,

which is the main purpose of this project.

Endjin uses an open-source framework called Backstage for building de-

veloper platforms [23], created by Spotify. Endjin uses it to track the de-

pendencies and components in their systems. It was designed to increase

the ability to centralising information and use the same format throughout,

maintaining consistency. As Endjin currently uses it as a development tool,

therefore it would be the ideal place to create an overall report page for the

vulnerability information.

The Backstage site would ideally display a summary of how many vulnerab-

ilities are in each severity band, and also a more in-depth view of the report

as a whole. The summary allows the reviewer to understand what the state

of the system is, which may influence whether they take action or not, for

example, if they see there are 5 critical vulnerabilities then it indicates there

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-30-2048.jpg)

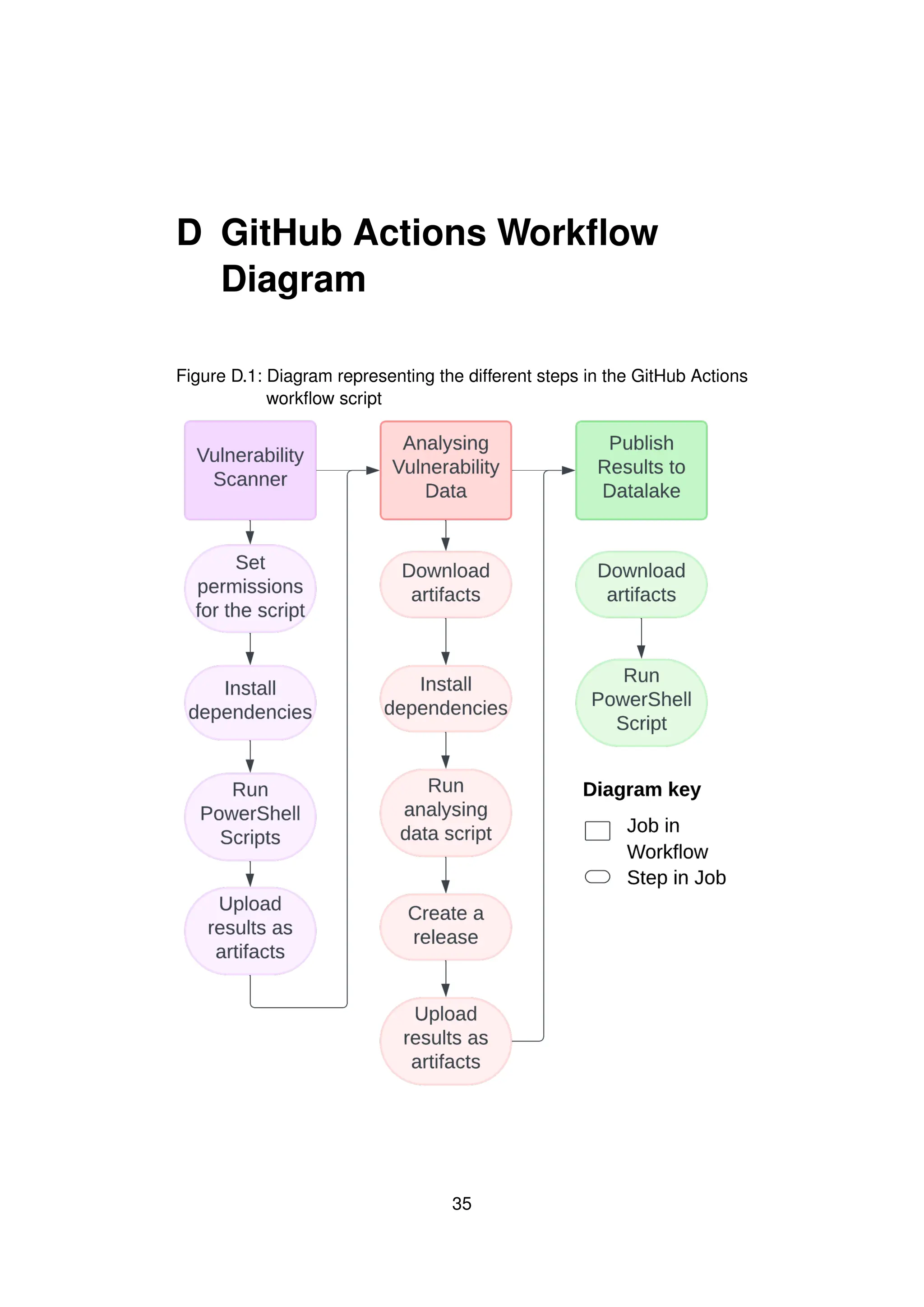

![6 Implementation

6.1 GitHub Actions Workflow

To individually group and run the scripts in this system, as described in

the design, I used GitHub Actions. The design describes different parts of

the system running individually and passing information along. I separated

these into separate jobs in the GitHub Actions workflow that can have

artifacts passed along the system. To do this I used a singular GitHub

Actions script which described each individual job, including which scripts

needed to be run, and also set up some extra conditions. Artifacts [33]

are a collection of files that allow information to be shared between jobs in

a workflow. For this project, artifacts can be used to pass data about the

SBOMs and vulnerability report between different stages of the process.

This means that data doesn’t need to be uploaded to the cloud between

steps, and the information doesn’t need to be written into the code of the

repository. It makes it easier to individually run these jobs, which makes it

easier to debug them, as mentioned in the design section of the report. At

the end of the system, these artifacts get published to the repository as a

release so that they can be checked as part of an end-to-end process?

Two separate parts of the workflow both connect to the Azure datalake

to either pull or push infomration. Access to information in the data lake

requires a token of access, the most relevant in this scenario is using a

SAS token. In Azure I can generate one of these codes and then add it

to the repositories secrets, which can then be referenced as environment

variables when the workflow runs. This makes it more secure to connect

to the data lake. Even if the repository is public, the token isn’t available

for anyone to see, even the user that added the token, so it is very safe.

Commands can then be made to the data lake which can get and put

information.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-32-2048.jpg)

![7 Evaluation

modularity it meant that not much of the code for the rest of the system

needed to be changed.

7.4 Synthesis

Following the feedback from Endjin regarding the implementation and re-

quirements for this project, along with the break-down of the functional and

non-functional requirements and the evidence from the overall functionality

of the system, it is clear that a workflow has been created that will be

beneficial to Endjin to move closer to becoming OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974

compliant. The workflow collects the SBOMs (which represent all the com-

ponents across Endjin’s codebase) and produces a vulnerability report that

provides information on the vulnerabilities found for certain components.

The OpenChain specification defines processes that should check ‘open

source Software against publicly known security vulnerabilities like CVEs,

GitHub/GitLab vulnerability reports’ [6], which is exactly what this workflow

does. As mentioned in the review with Endjin, the stakeholders say that

this will bring them closer to becoming OpenChain compliant from an

implementation stance, and they will integrate this into their current systems,

in fact have already started working on it. The system will ensure the open-

source software they use has been checked for vulnerabilities, and the

resulting data can be used to update their components autonomously.

The OpenChain ISO/IEC 18974 is a brand new specification meaning

there is room for growth and development around the management of open-

source software from a security perspective. There are many state of the art

tools that currently exist for scanning vulnerabilities, however the application

of the specification to the individual organisation is what makes this project

unique. Now that Endjin has a new system which seamlessly integrates

with their current architecture, it will be easy to add extra functionality if the

state of the art develops or if there are any changes to the standard.

As mentioned in the project aim, this project aims to create a system for

Endjin that will aid the implementation of the OpenChain specification and

can be integrated seamlessly into their current architecture. A lot of the

decisions around the design of this project were based on the requirement

for the workflow to be similar to Endjin’s current architecture, these were

then reflected in the implementation. Endjin, as stakeholders in this project,

state that it will be easy for them to maintain and integrate into their current

systems.

29](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-38-2048.jpg)

![Bibliography

[1] L. Zhao and S. Elbaum, ‘Quality assurance under the open source

development model,’ Journal of Systems and Software, vol. 66,

no. 1, pp. 65–75, 2003, ISSN: 0164-1212. DOI: https : / / doi . org /

10.1016/S0164-1212(02)00064-X. [Online]. Available: https://www.

sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S016412120200064X.

[2] Endjin.com, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://endjin.com/.

[3] Openchain iso/iec 18974 - security assurance, OpenChain, 2023.

[Online]. Available: https : / / www. openchainproject . org / security -

assurance.

[4] Openchain iso/iec 5230 - license compliance, OpenChain, 2023.

[Online]. Available: https : / / www. openchainproject . org / license -

compliance.

[5] J. Dawson, James dawson - principal i. [Online]. Available: https:

//endjin.com/who-we-are/our-people/james-dawson/.

[6] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/OpenChain-Project/

Security-Assurance-Specification/blob/main/Security-Assurance-

Specification/DIS-18974/en/DIS-18974.md.

[7] J. Lindner, Open source software statistics [fresh research] gitnux,

2023. [Online]. Available: https://gitnux.org/open-source-software-

statistics/.

[8] R. Shewale, Android statistics for 2024 (market share & users), 2023.

[Online]. Available: https://www.demandsage.com/android-statistics/.

[9] [Online]. Available: https://logging.apache.org/log4j/2.x/.

[10] [Online]. Available: https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/information/log4j-

vulnerability-what-everyone-needs-to-know.

[11] C. Eng, B. Roche, N. Trauben, R. Haynes and C. Eng, State of log4j

vulnerabilities: How much did log4shell change? [Online]. Available:

https://www.veracode.com/blog/research/state-log4j-vulnerabilities-

how-much-did-log4shell-change.

[12] [Online]. Available: https://www.blackberry.com/us/en/company/

newsroom/press-releases/2022/blackberry-announces-first-openchain-

security-assurance-specification-conformance-in-the-americas.

[13] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/patriksvensson/covenant.

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-46-2048.jpg)

![Bibliography

[14] 2022. [Online]. Available: https://nvd.nist.gov/.

[15] 2022. [Online]. Available: https://nvd.nist.gov/general/cve-process#:~:

text=Founded%20in%201999%2C%20the%20CVE,Infrastructure%

20Security%20Agency%20(CISA)..

[16] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/anchore/grype.

[17] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/anchore/syft.

[18] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://anchore.com/.

[19] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/devops-kung-fu/bomber.

[20] 2021. [Online]. Available: https://spdx.dev/.

[21] 2022. [Online]. Available: https://osv.dev/.

[22] I. Sonatype, Sonatype oss index, 2018. [Online]. Available: https:

//ossindex.sonatype.org/.

[23] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://snyk.io/.

[24] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://docs.docker.com/scout/.

[25] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://fossa.com/product/open-source-

vulnerability-management.

[26] 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.vigilant-ops.com/products/.

[27] GitLab, What is devops? 2023. [Online]. Available: https://about.

gitlab.com/topics/devops/.

[28] GitLab, What is ci/cd? 2023. [Online]. Available: https://about.gitlab.

com/topics/ci-cd/.

[29] GfG, Requirements engineering process in software engineering,

2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/software-

engineering-requirements-engineering-process/.

[30] I. Sommerville, Software engineering. Addison-Wesley, 2007.

[31] [Online]. Available: https://enkonix.com/blog/functional-requirements-

vs-non-functional/.

[32] [Online]. Available: https://docs.github.com/en/issues/organizing-

your-work-with-project-boards/managing-project-boards/about-

project-boards.

[33] [Online]. Available: https : / / docs. github. com / en / actions / using -

workflows/storing-workflow-data-as-artifacts.

38](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/openchainiso18974dissertation-240814162948-5c6fa6e7/75/Charlotte-Gayton-s-OpenChain-ISO-18974-Dissertation-47-2048.jpg)