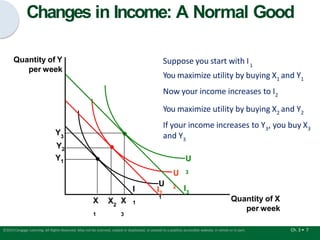

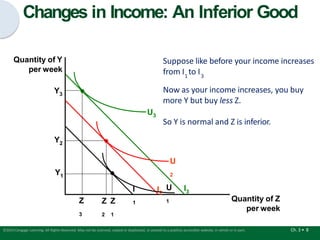

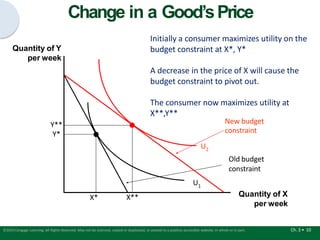

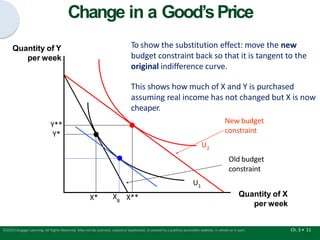

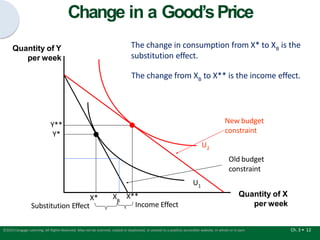

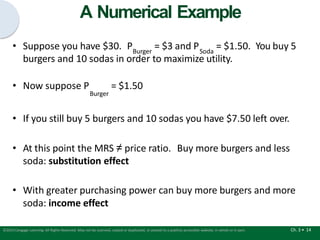

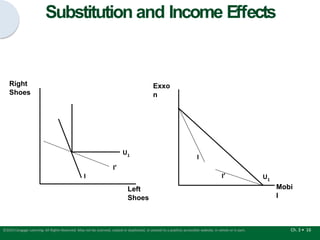

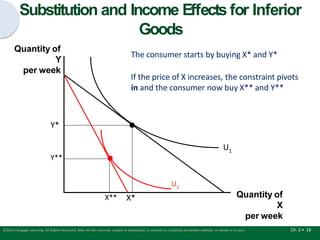

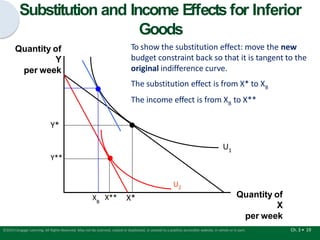

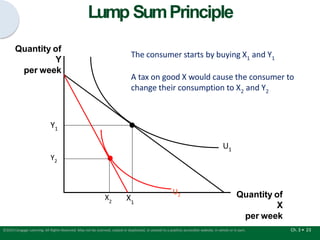

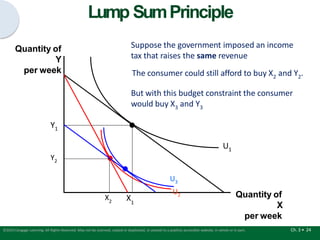

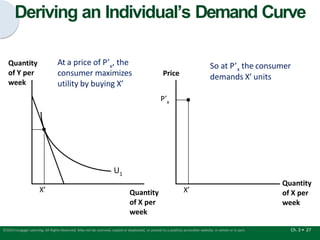

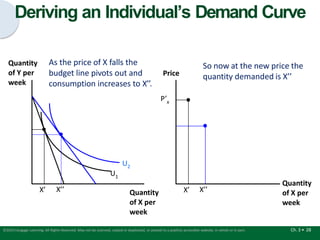

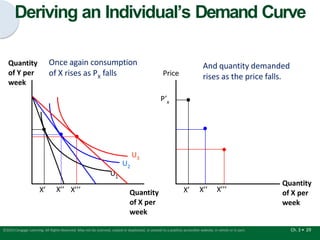

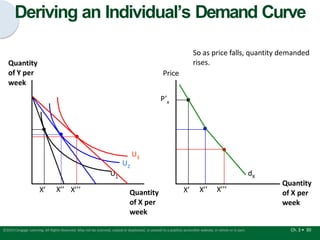

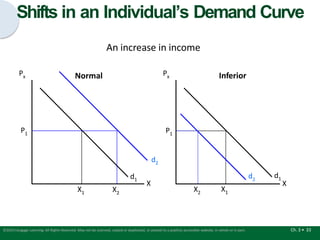

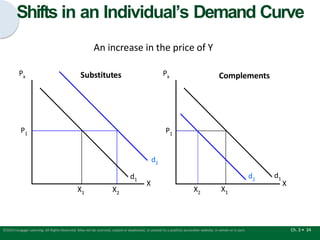

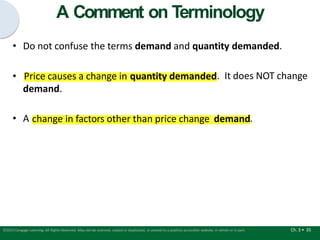

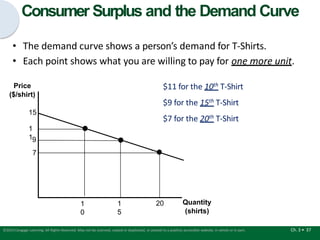

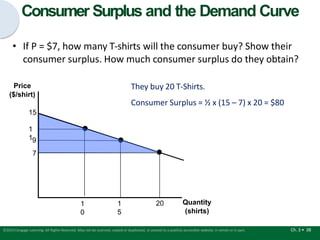

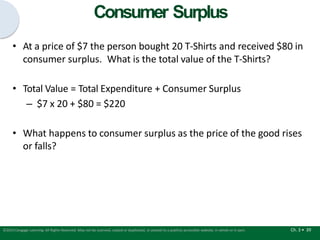

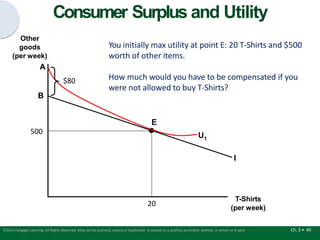

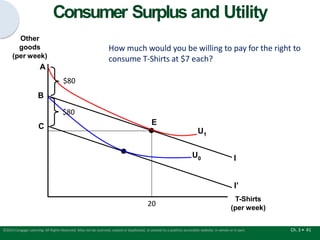

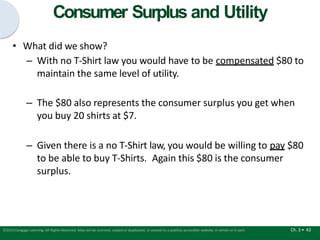

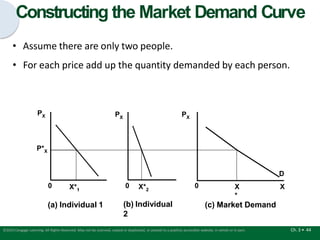

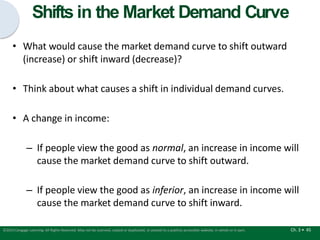

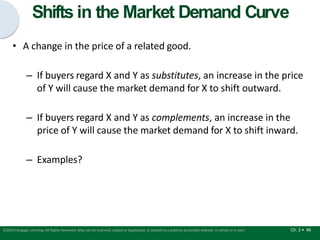

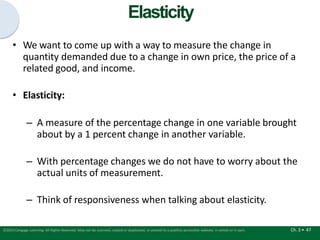

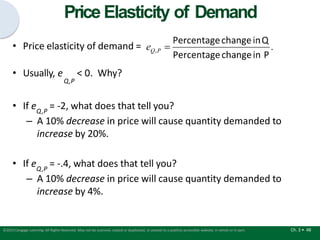

The document provides an overview of how to derive an individual's demand curve from their utility maximization model. It discusses how an individual's demand for a good depends on the price of the good, income, and prices of other goods. It shows graphically how as the price of a good decreases, the budget constraint pivots outward, allowing the individual to consume more of the good. By plotting quantity demanded at different price levels, an downward-sloping demand curve can be derived. The document also discusses how the demand curve can shift due to changes in factors like income, preferences, and relative prices.