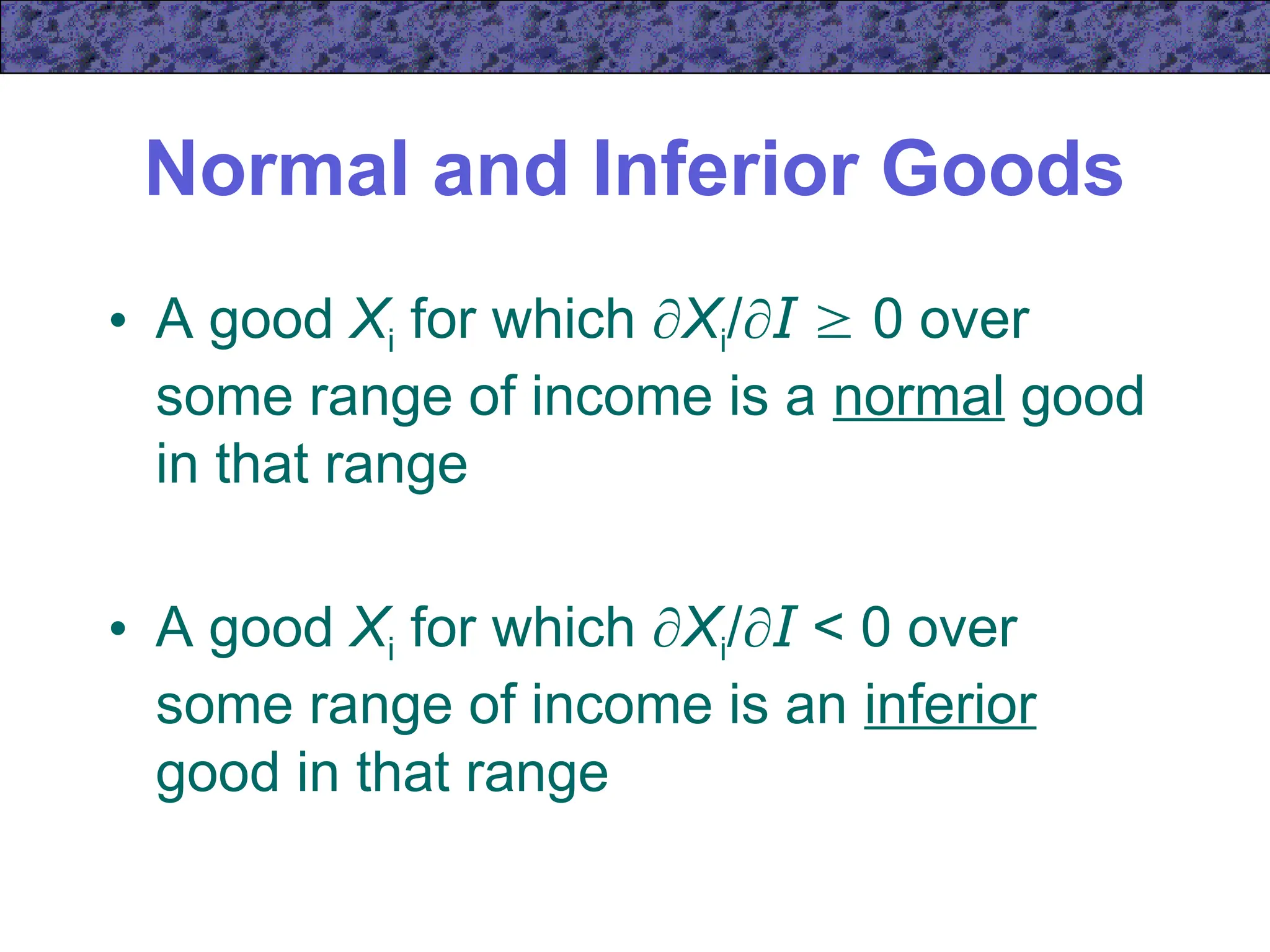

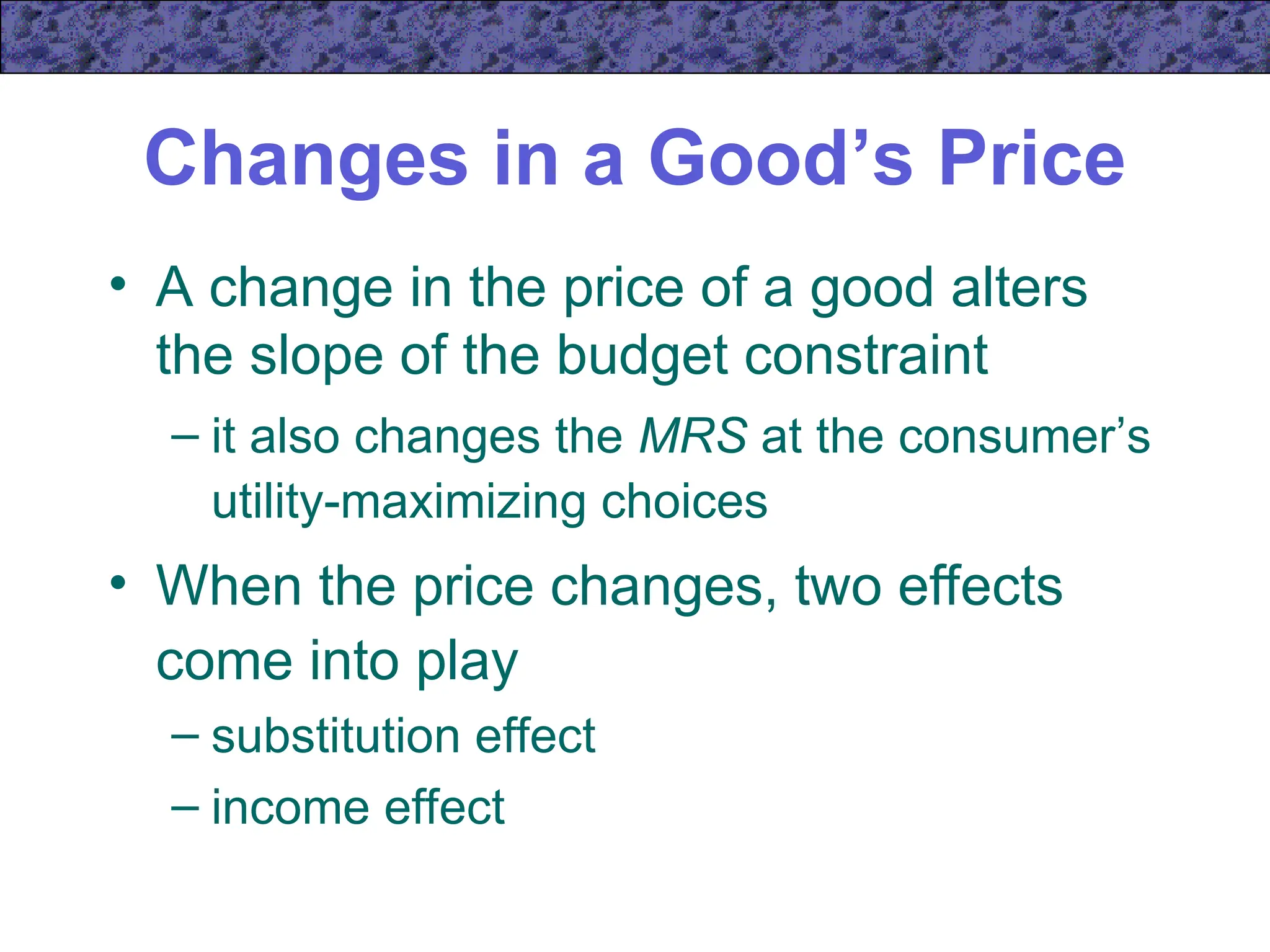

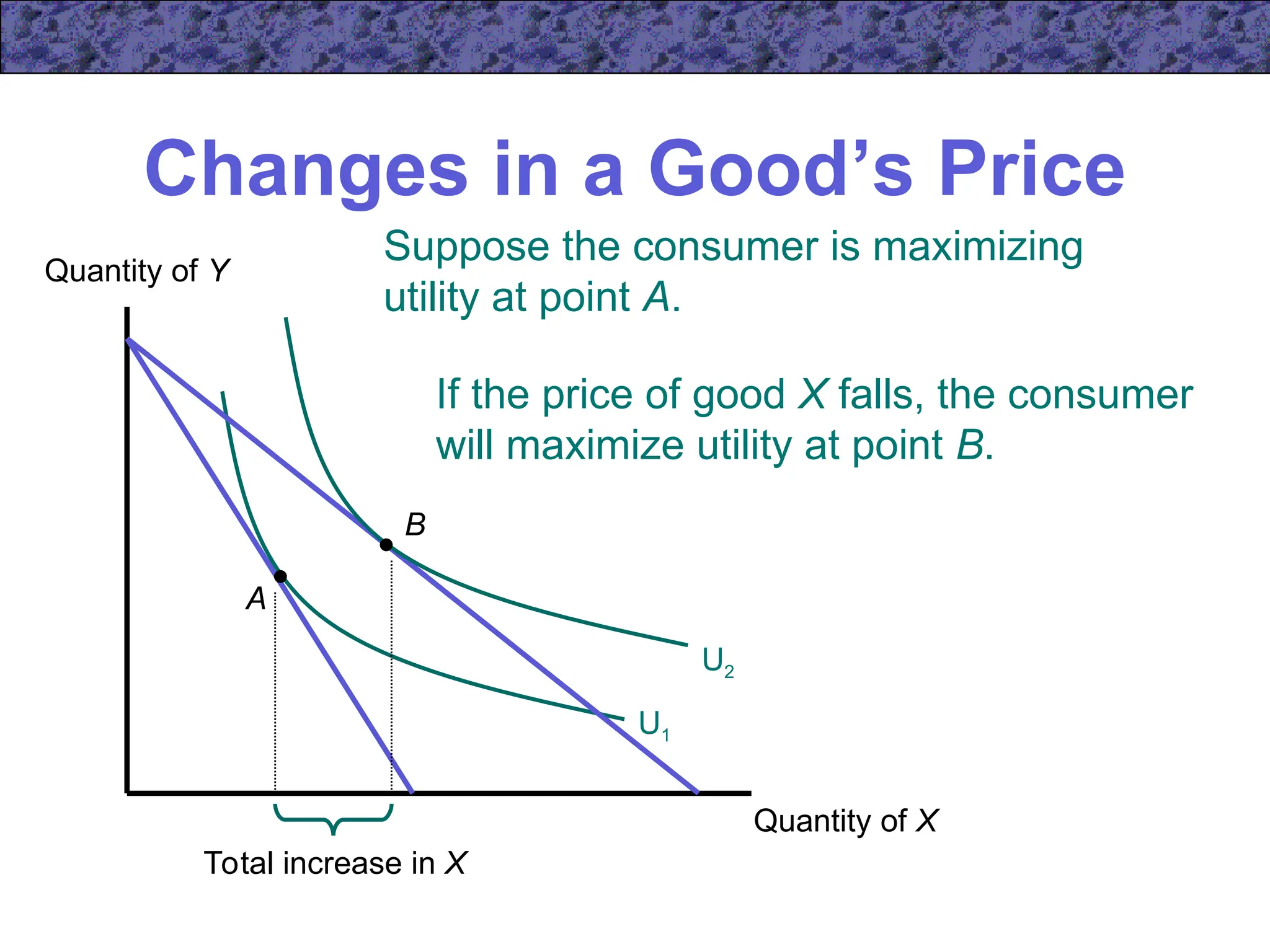

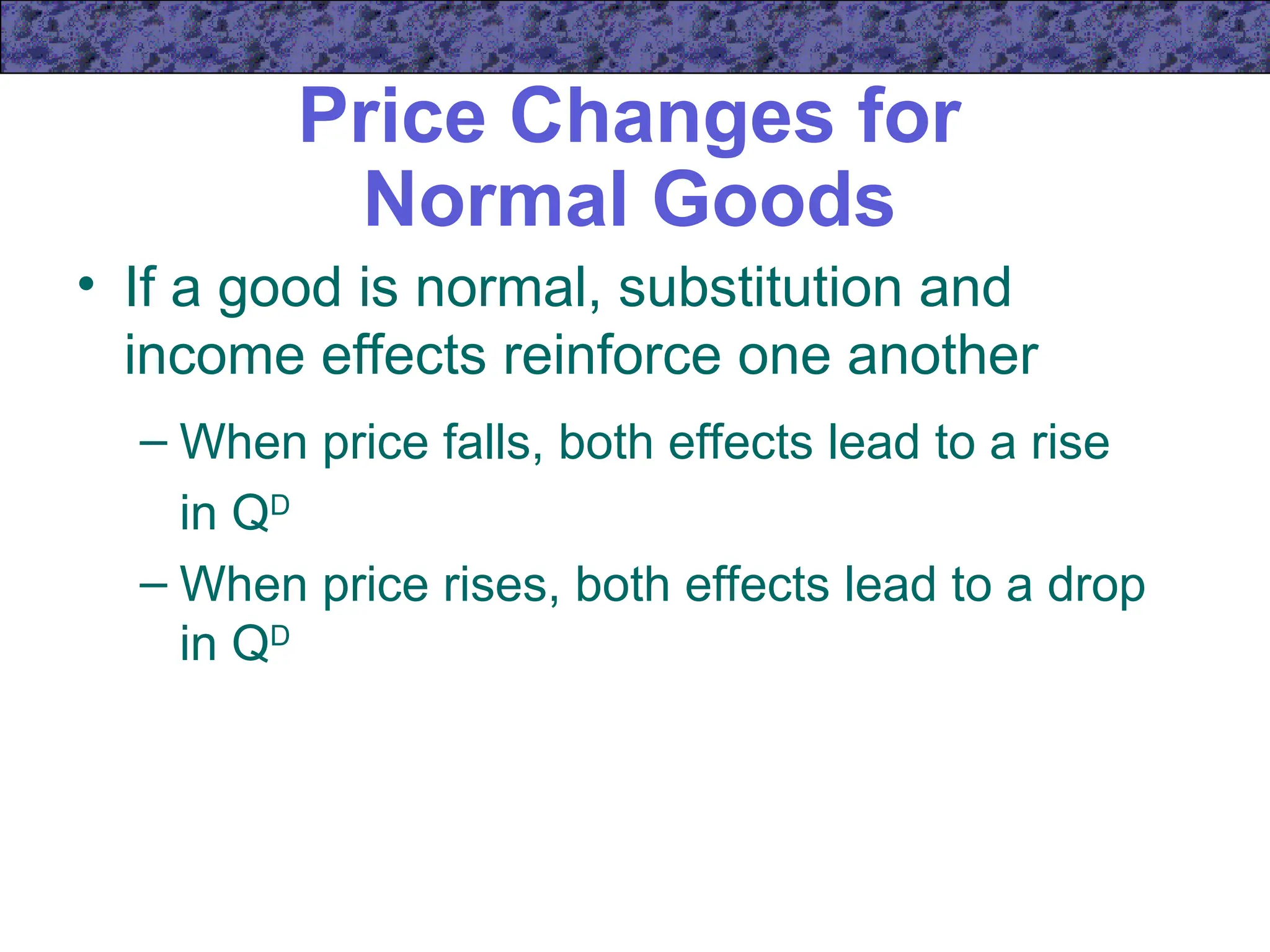

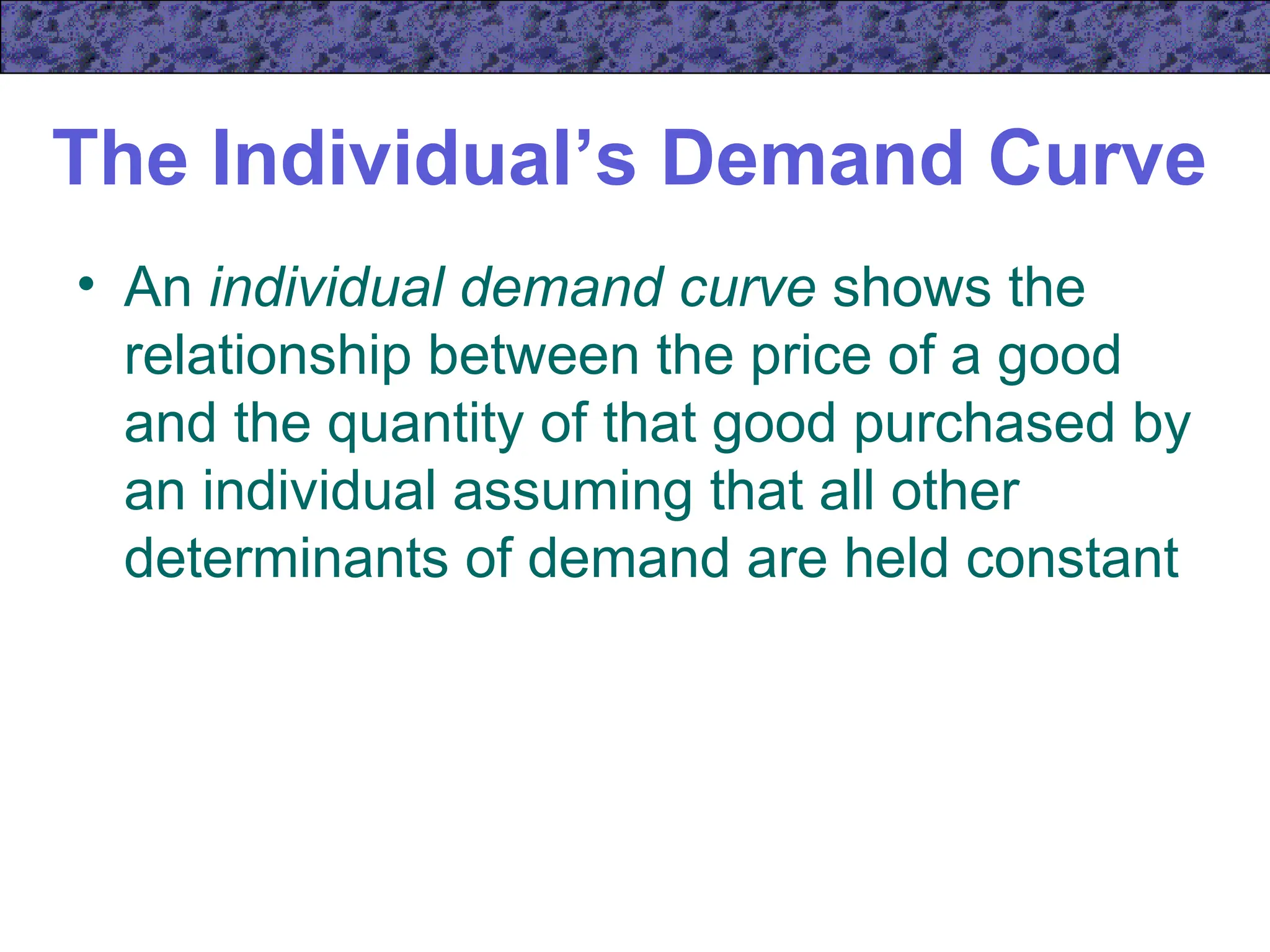

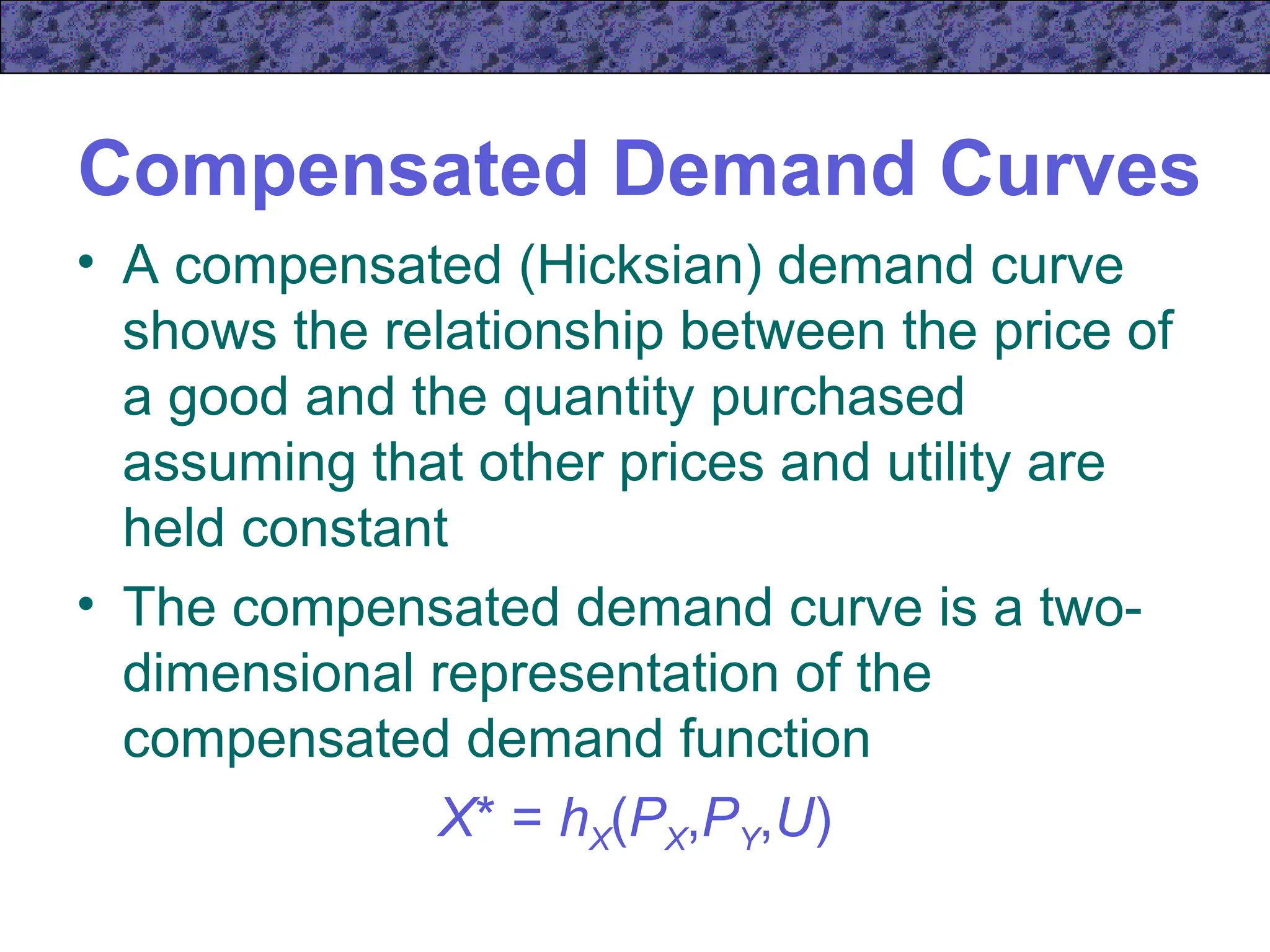

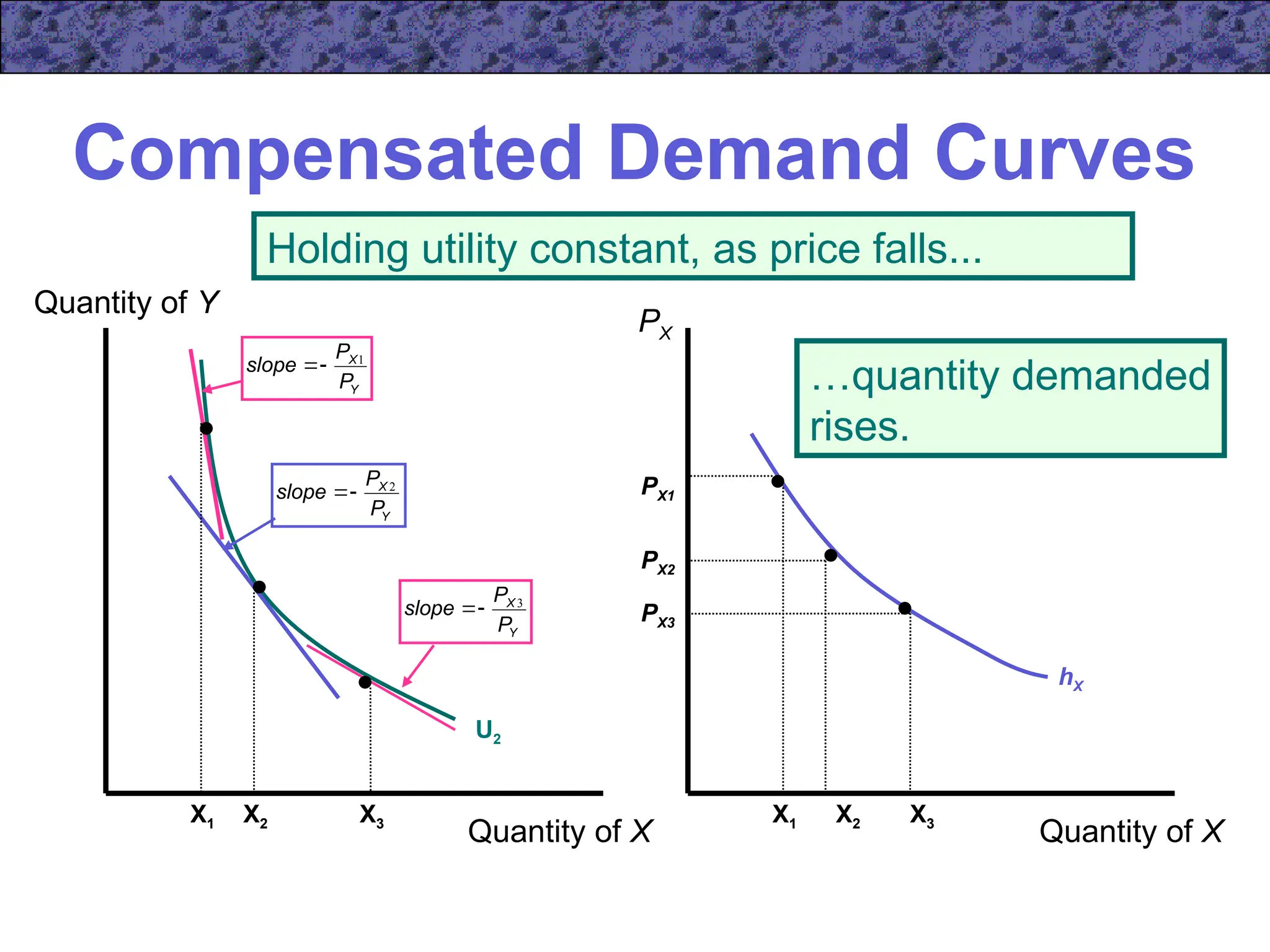

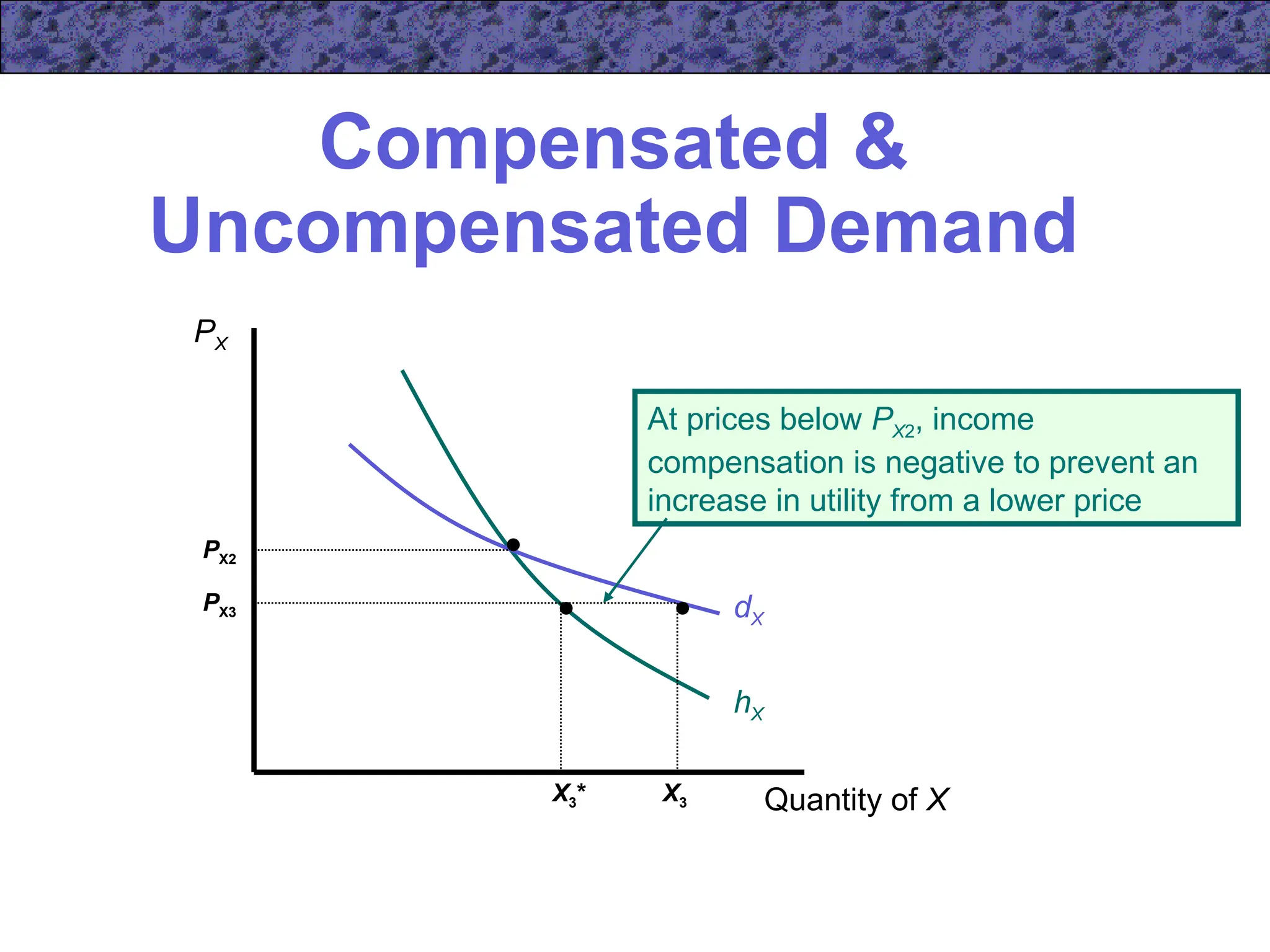

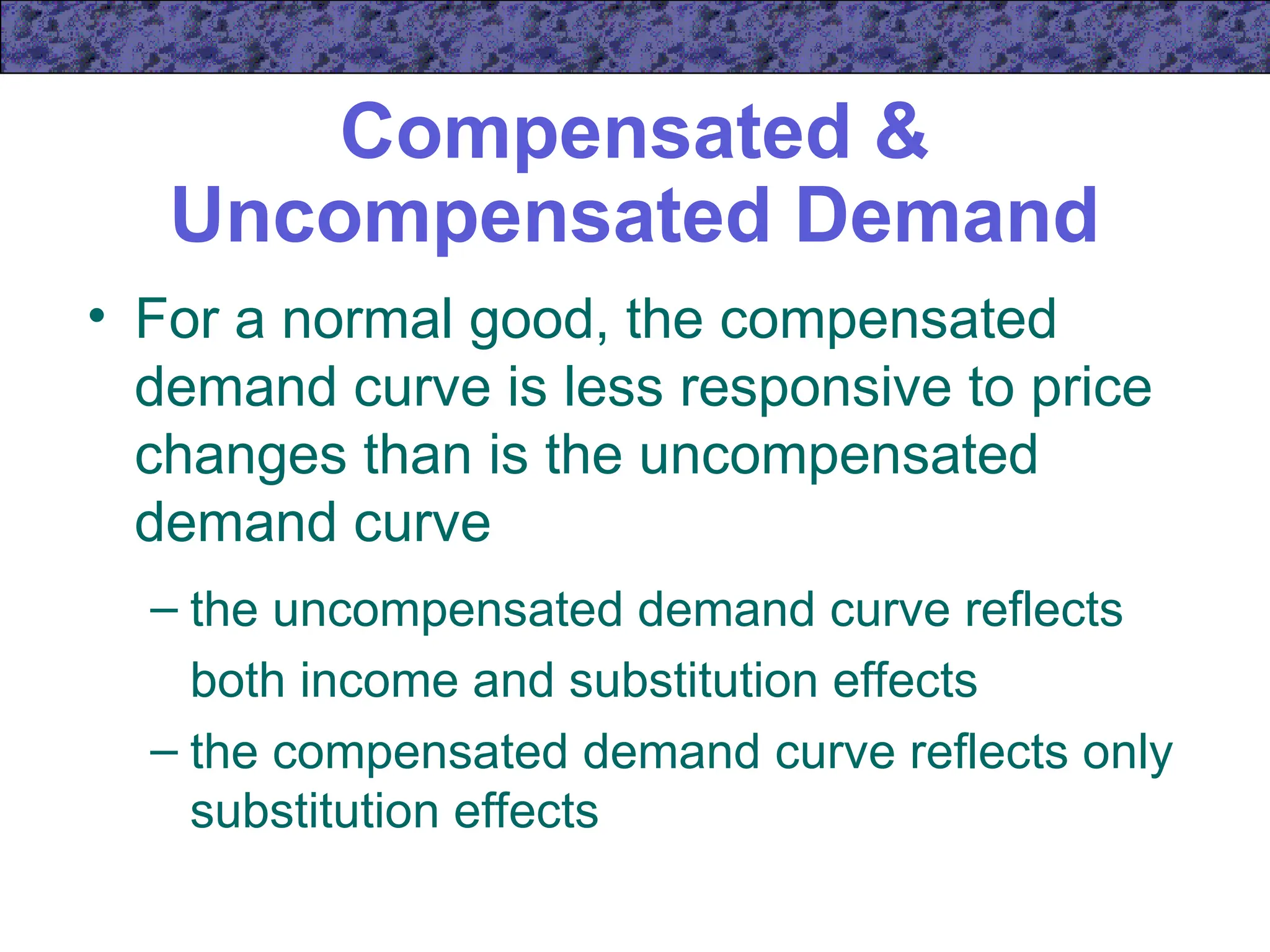

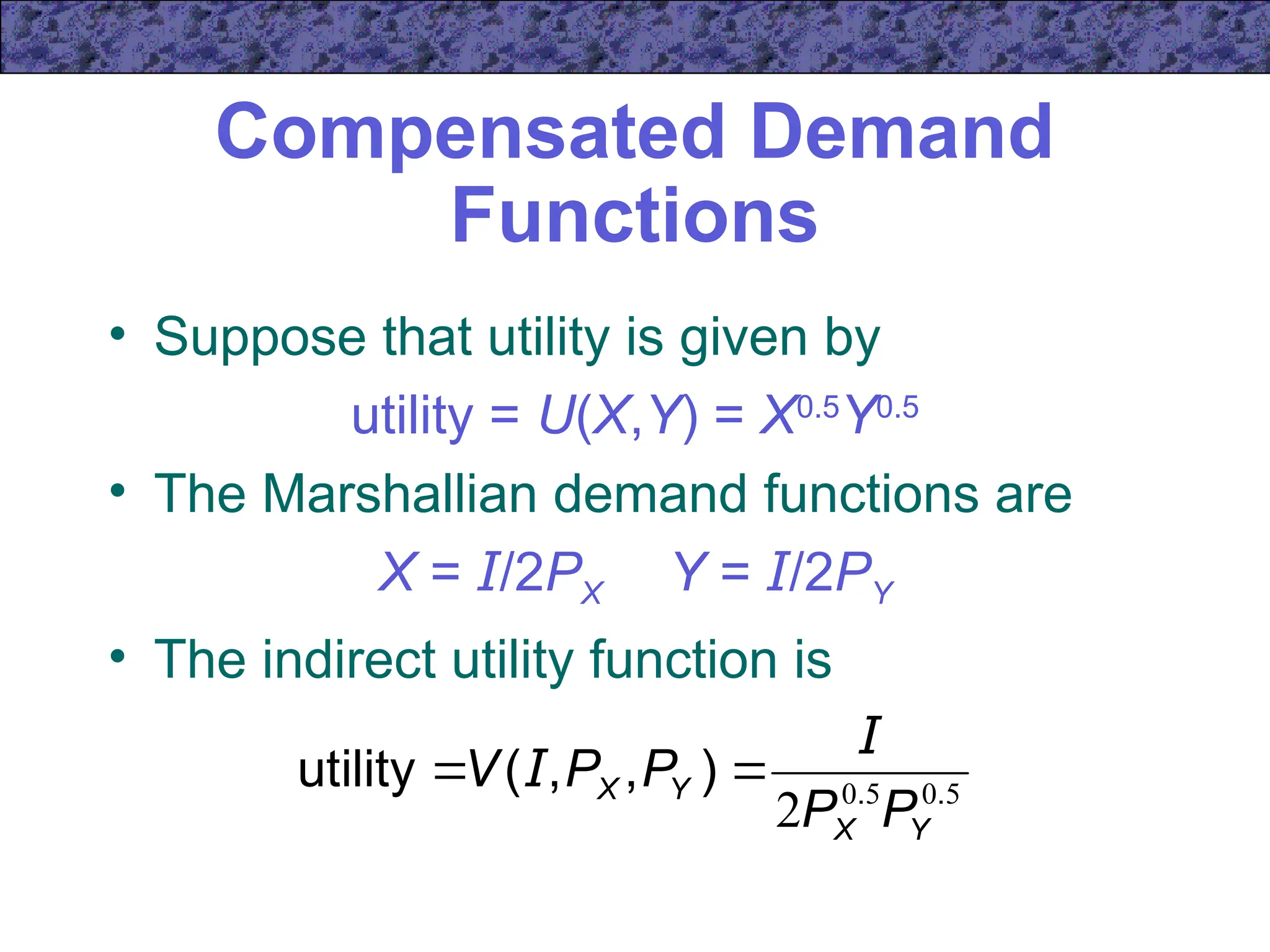

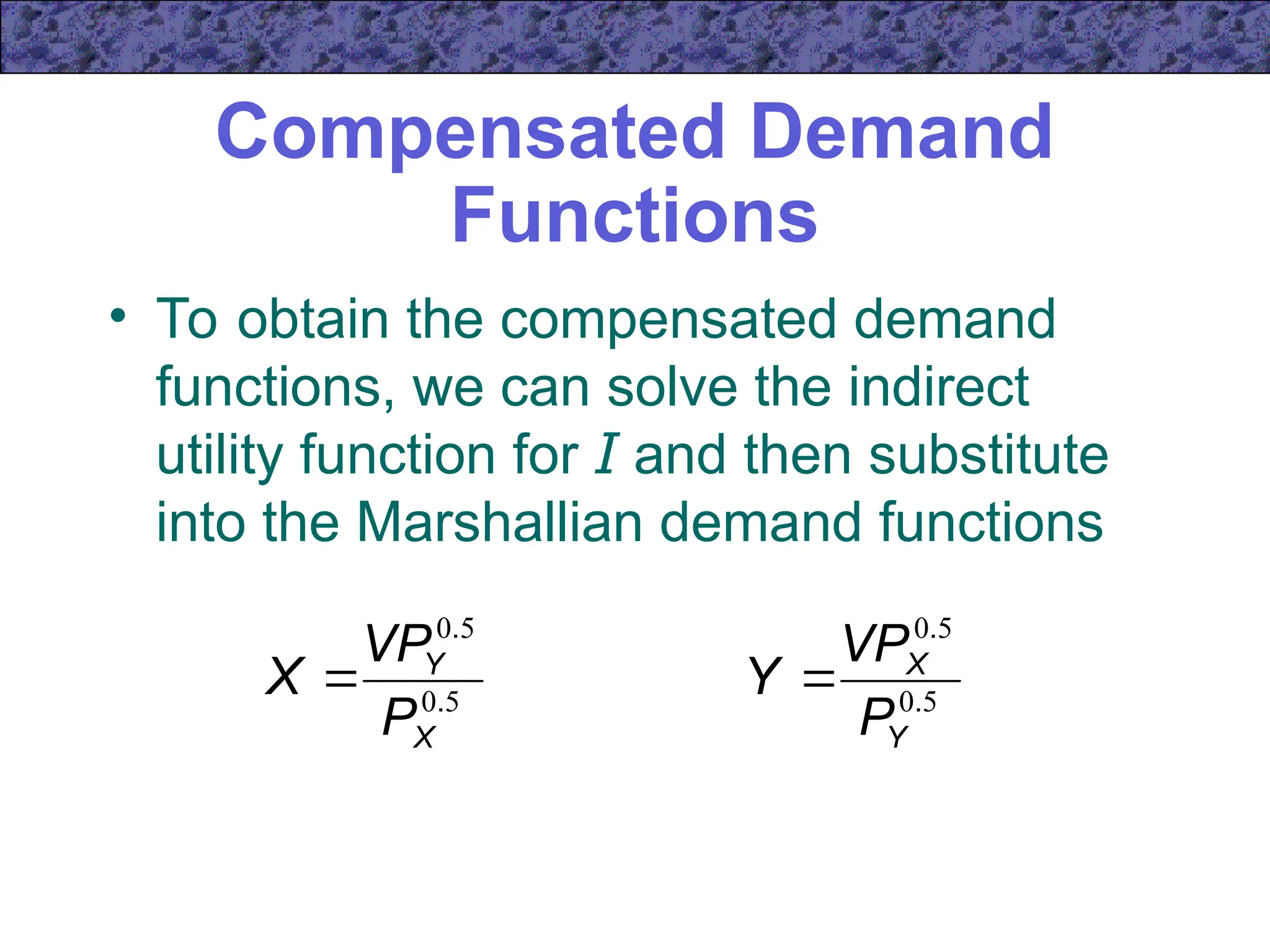

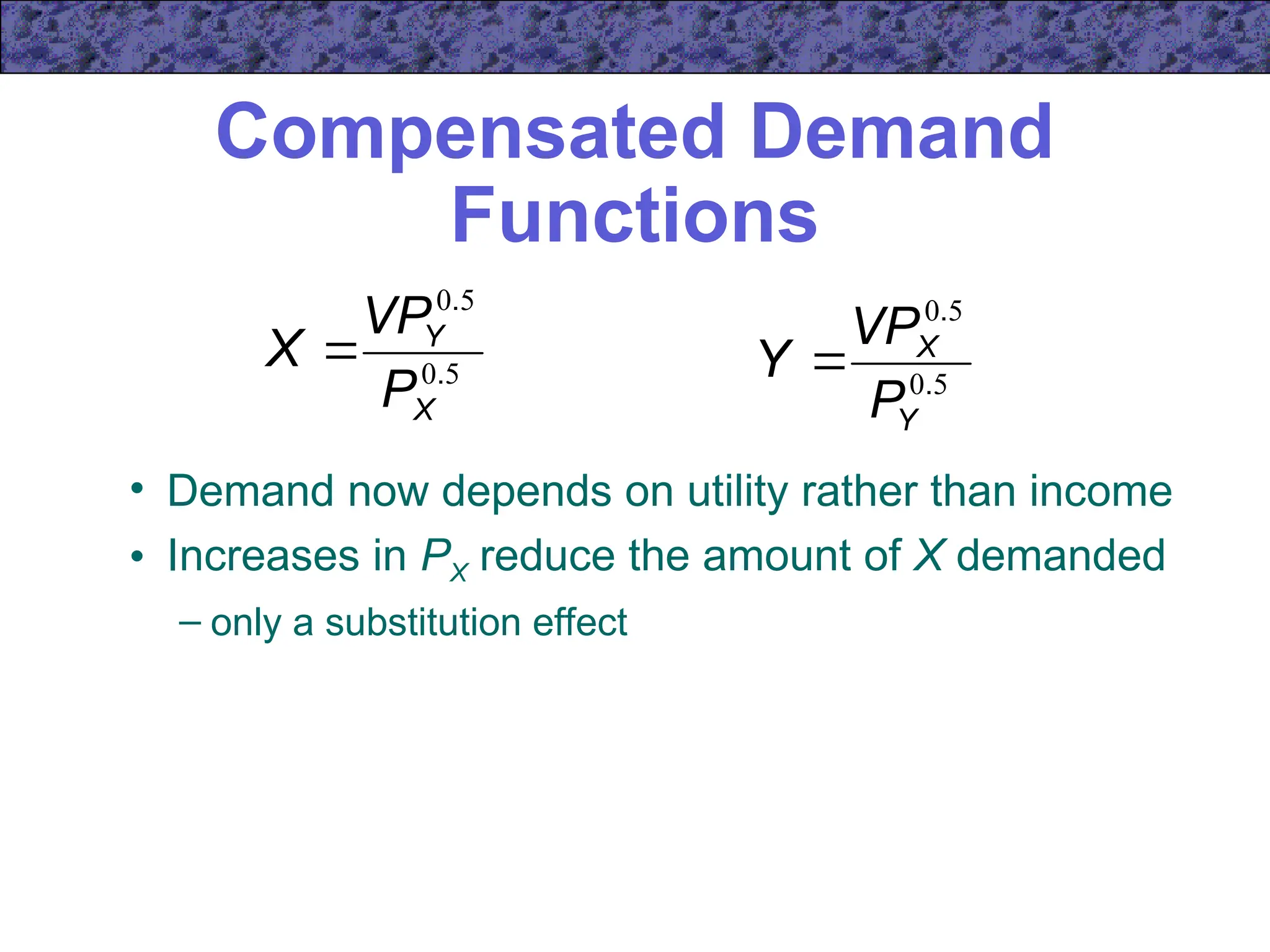

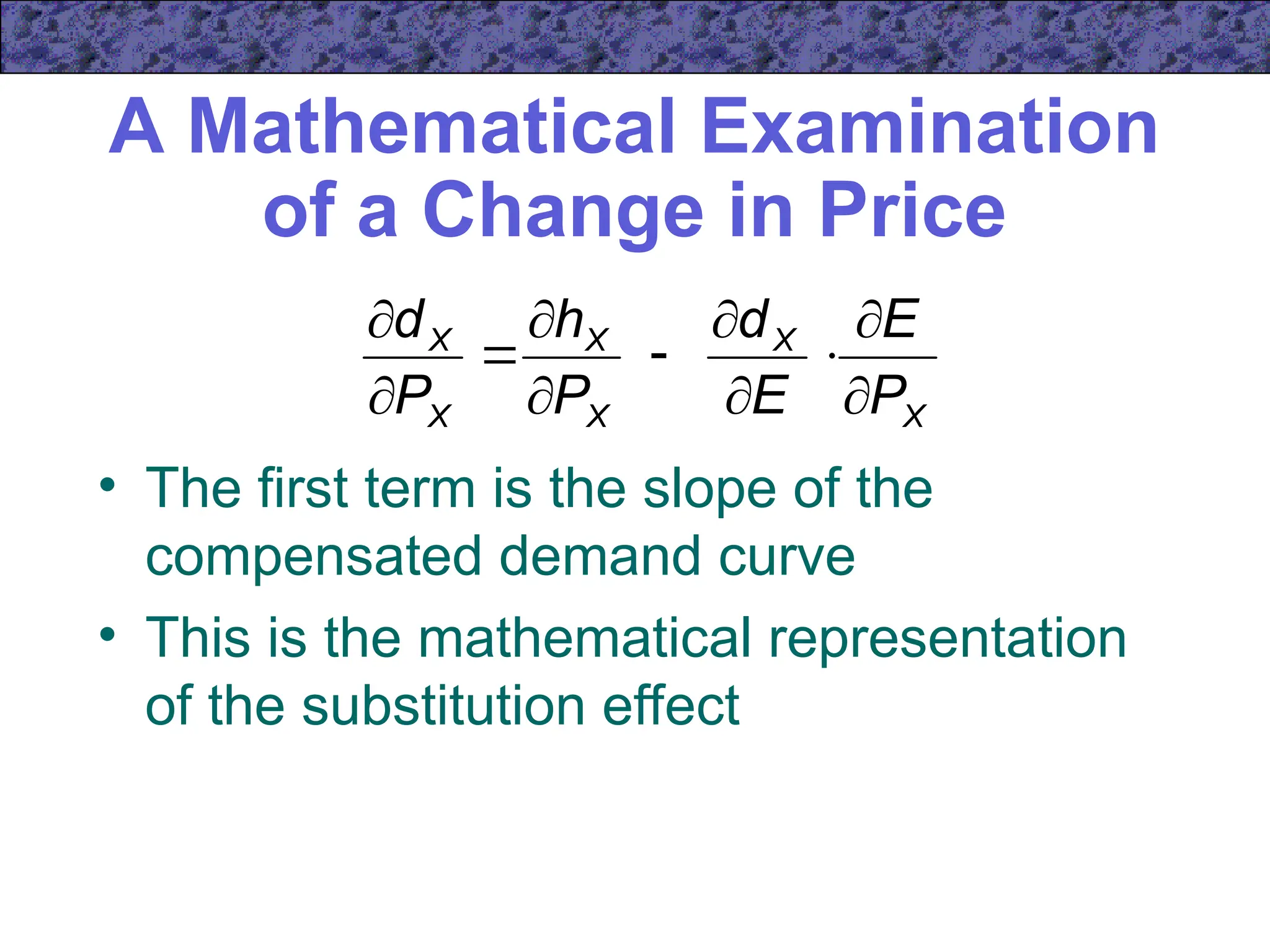

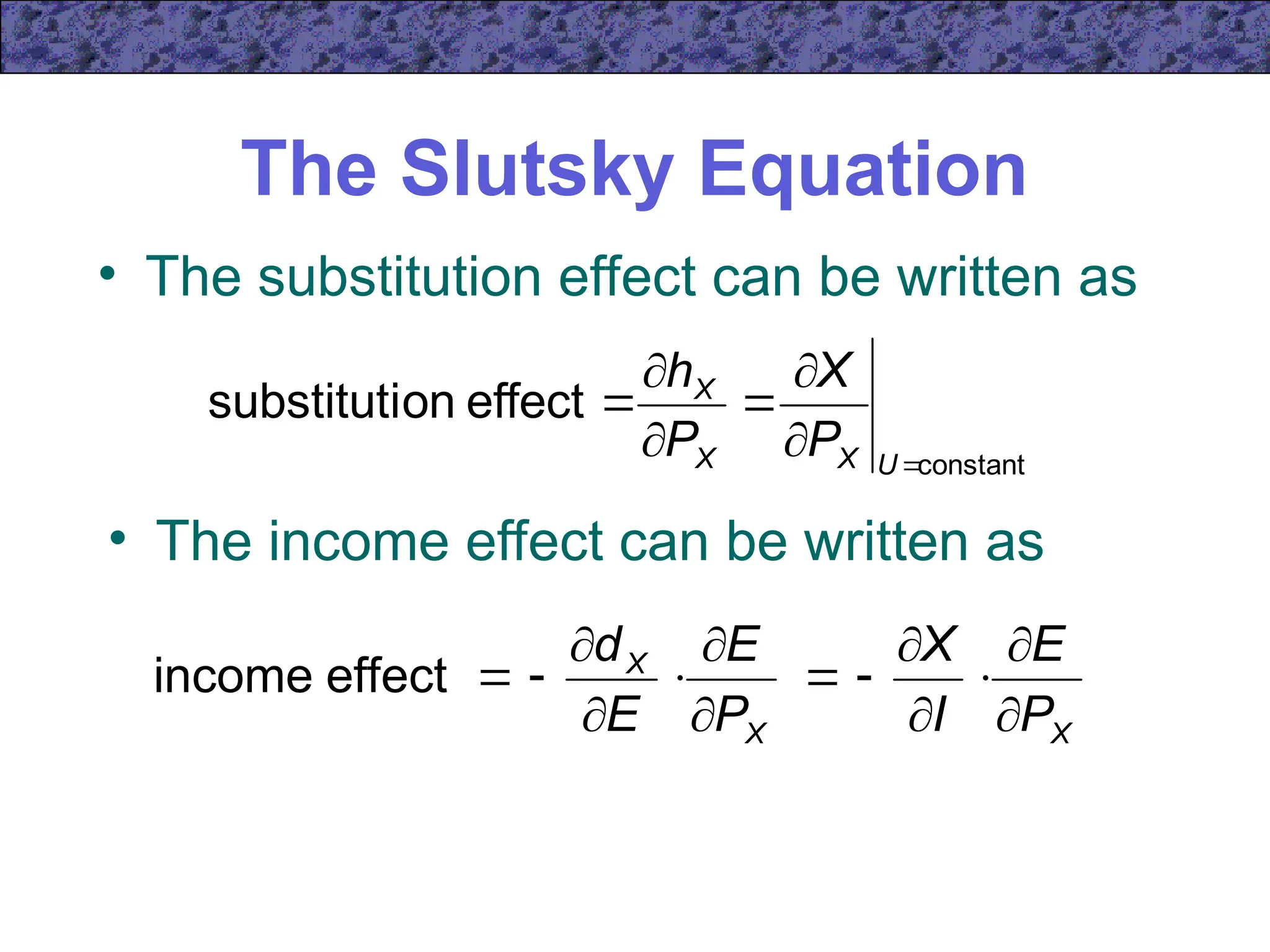

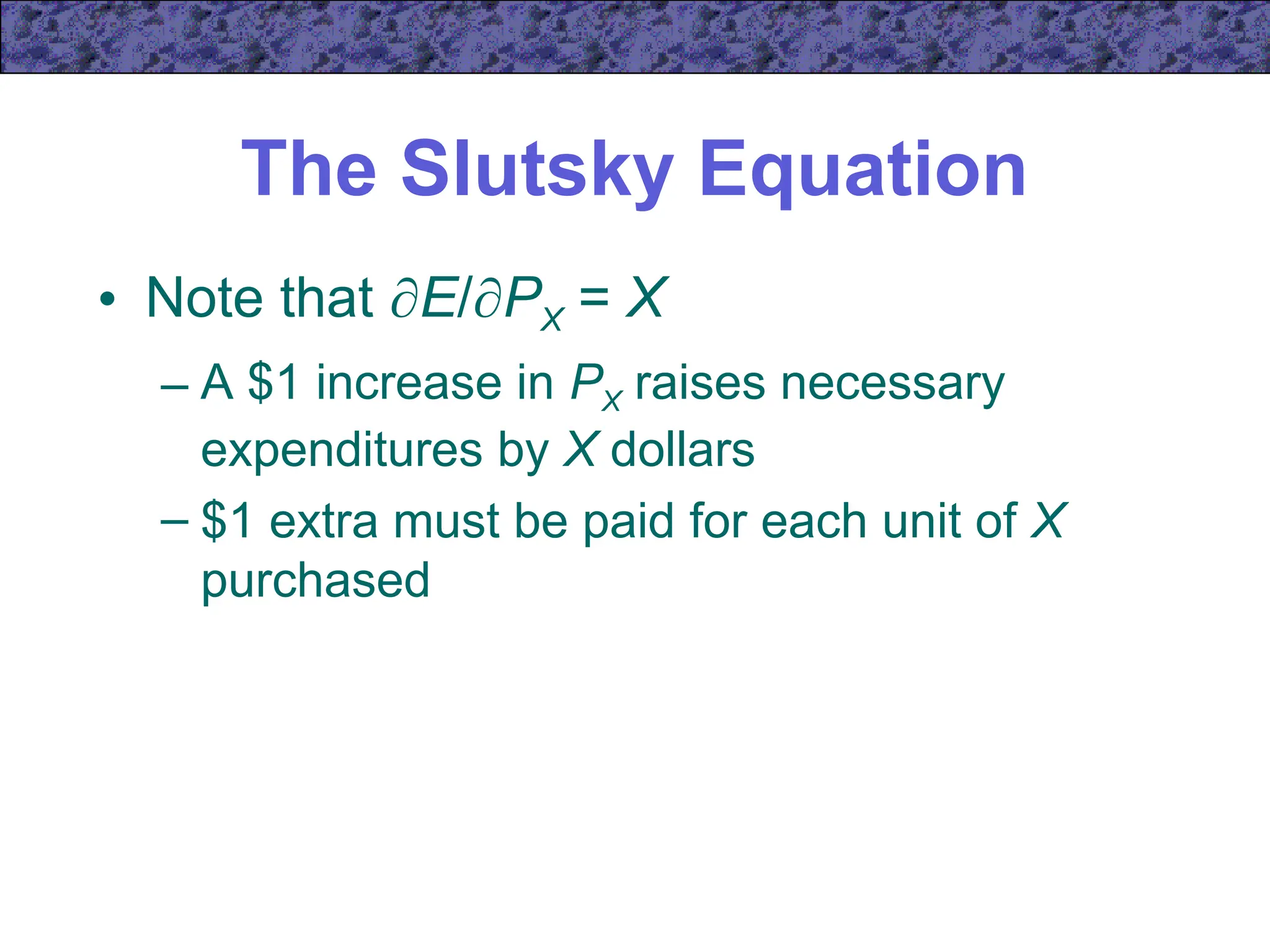

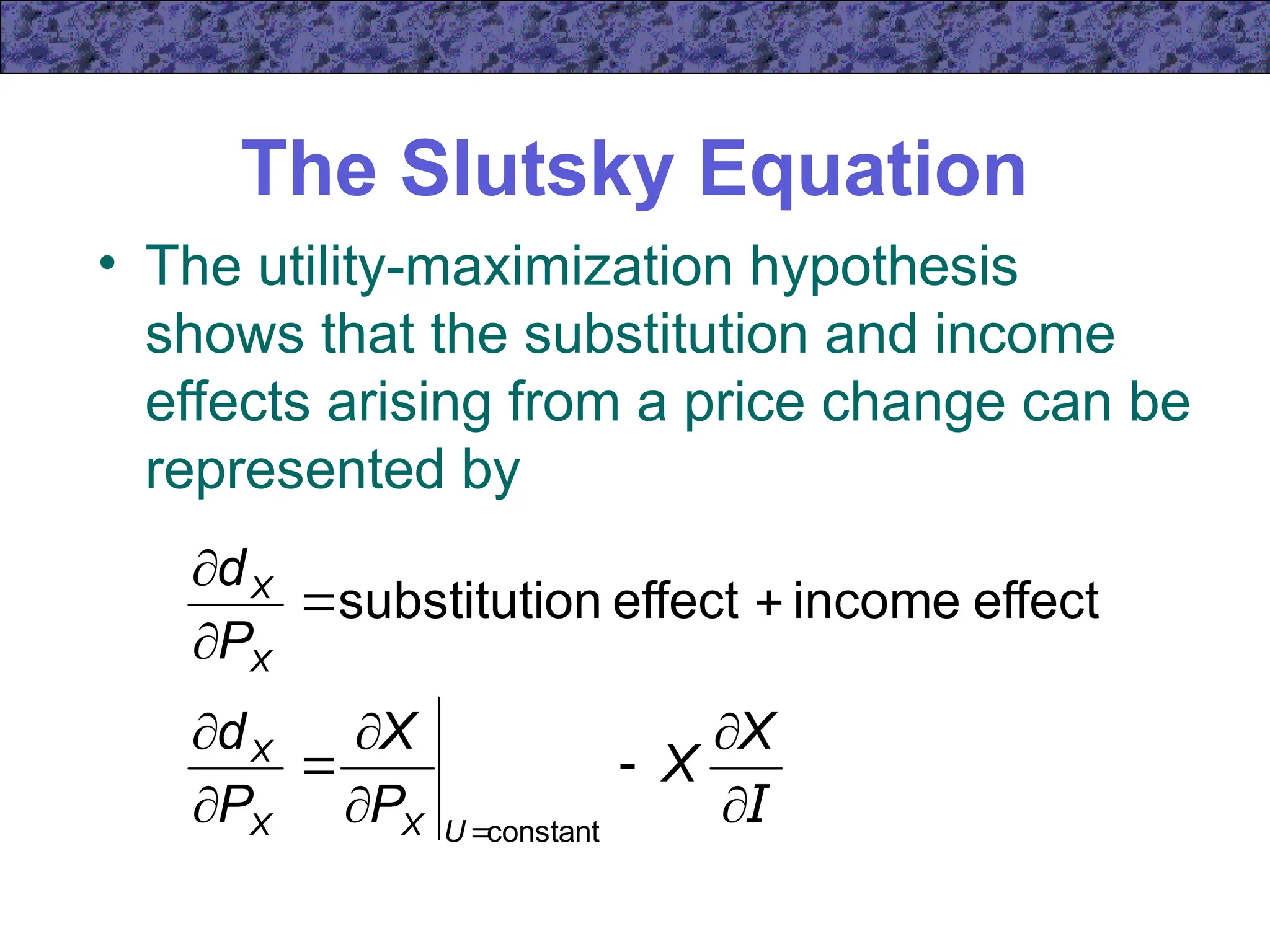

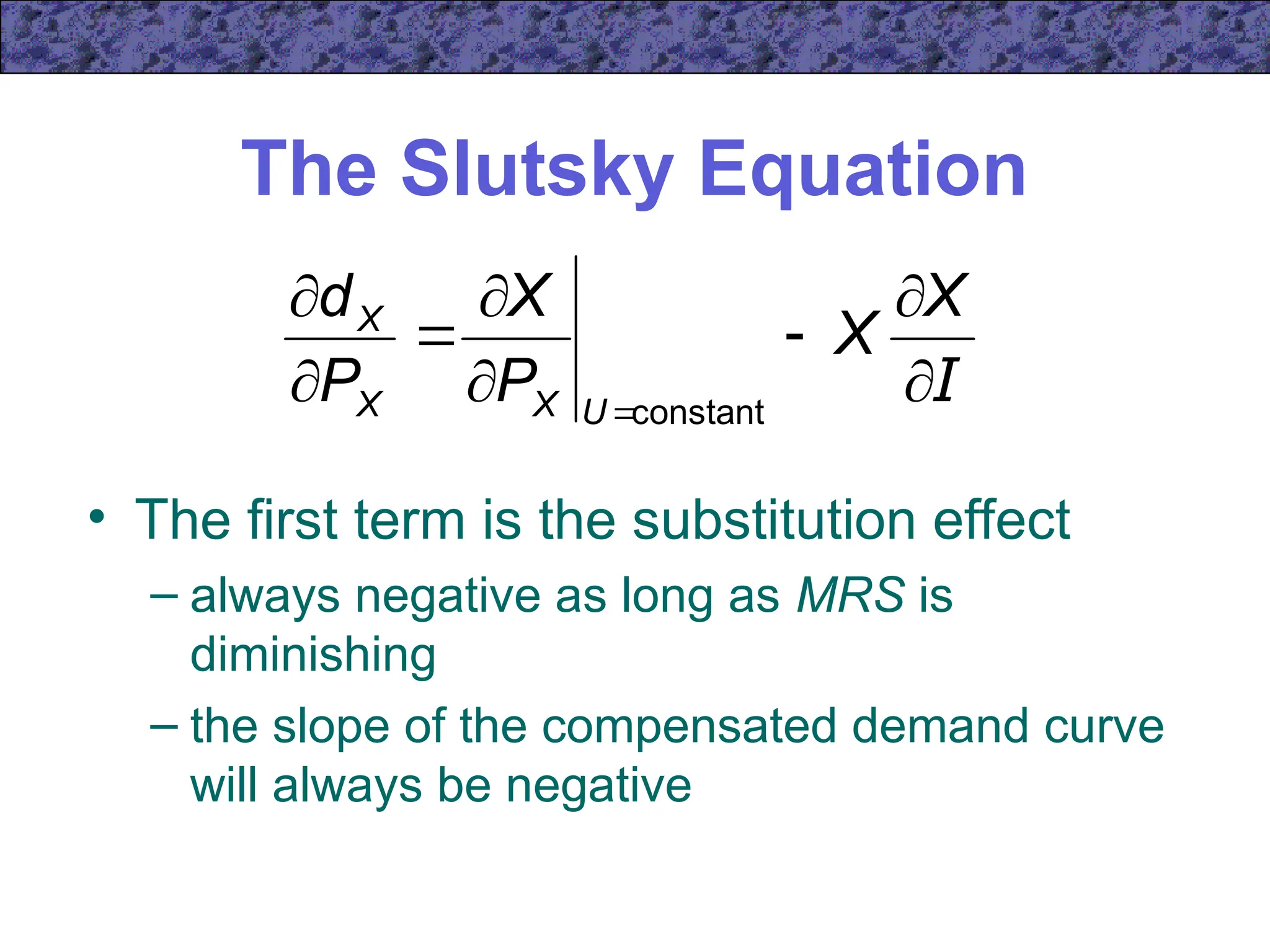

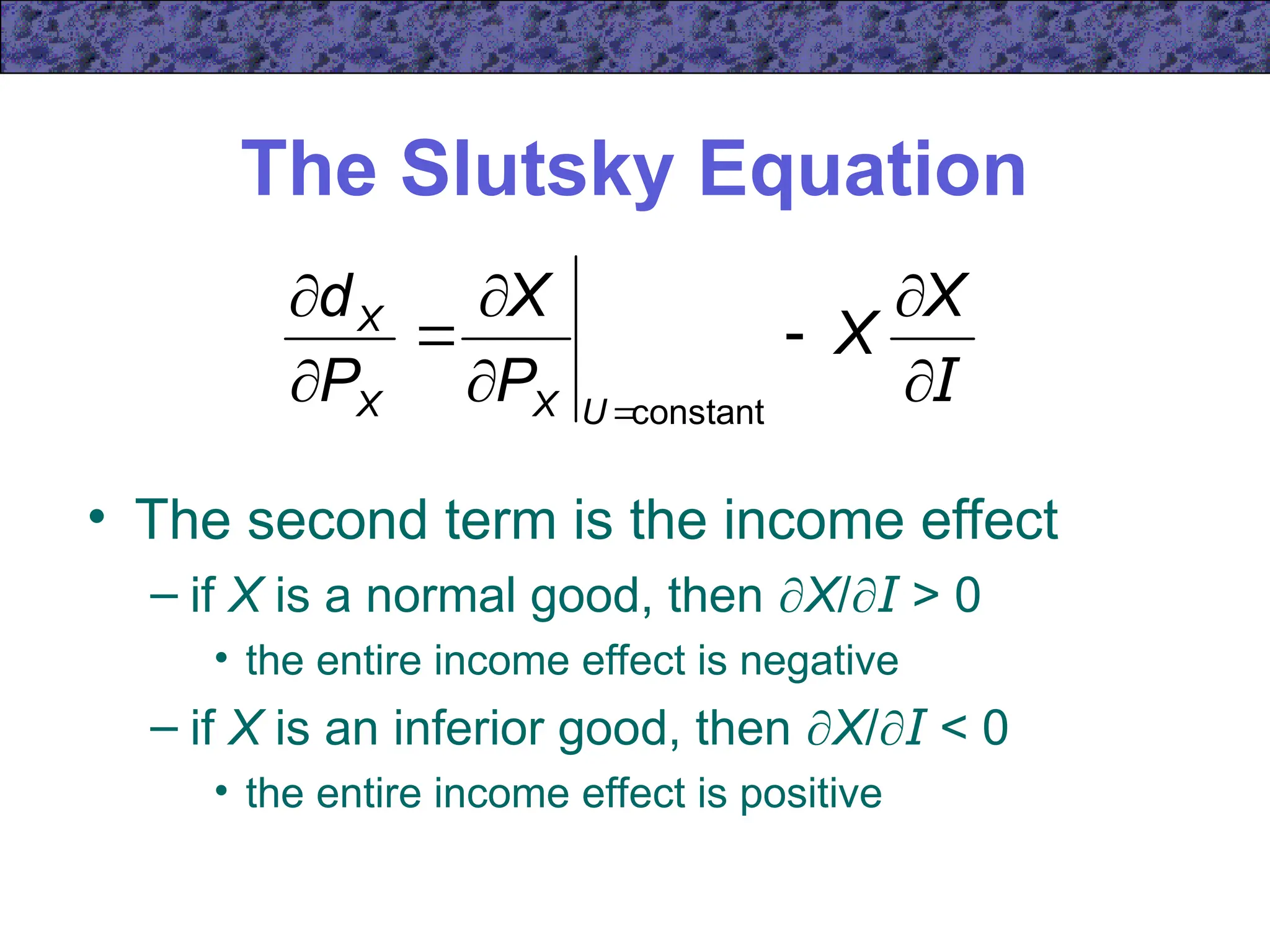

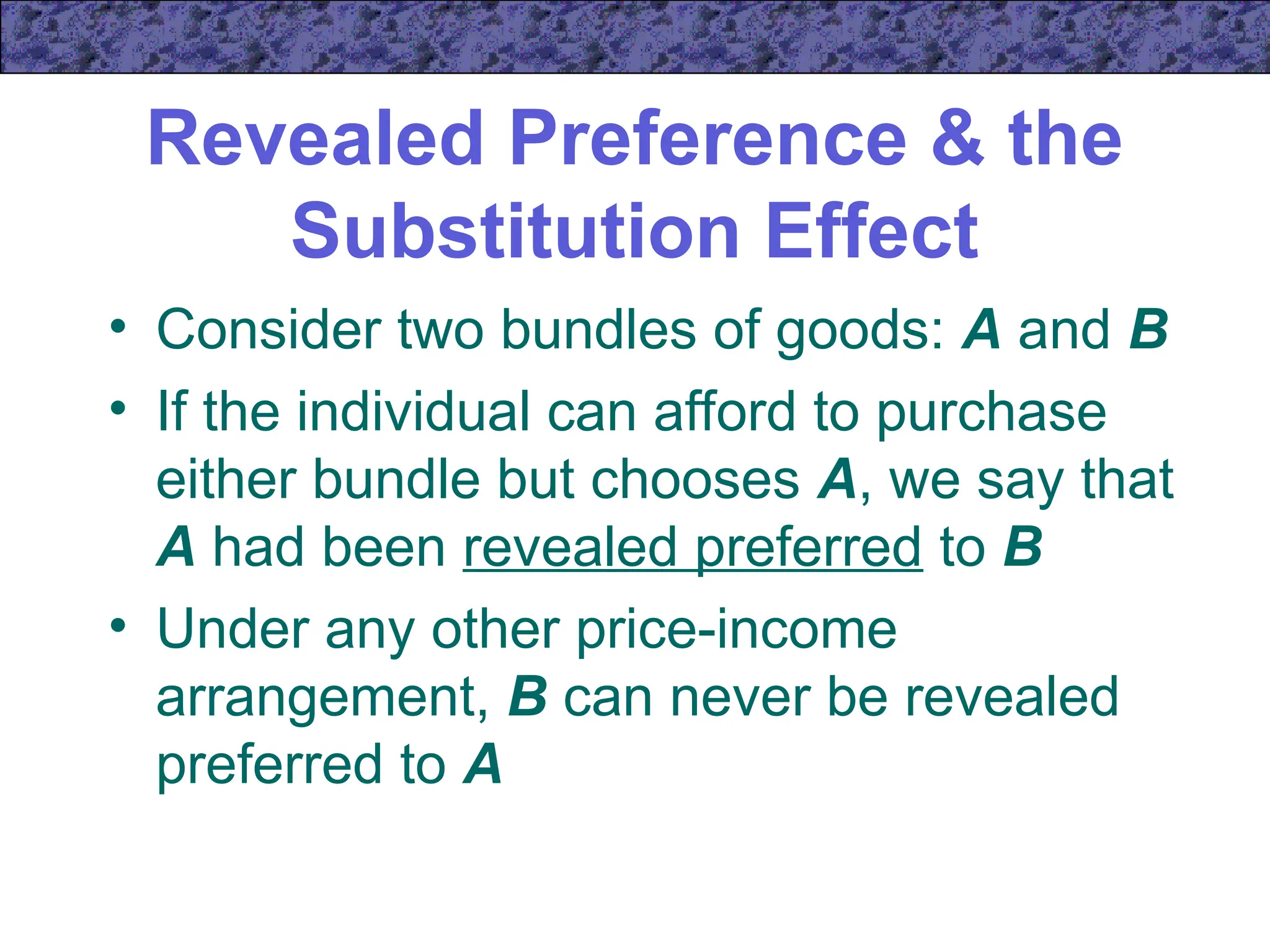

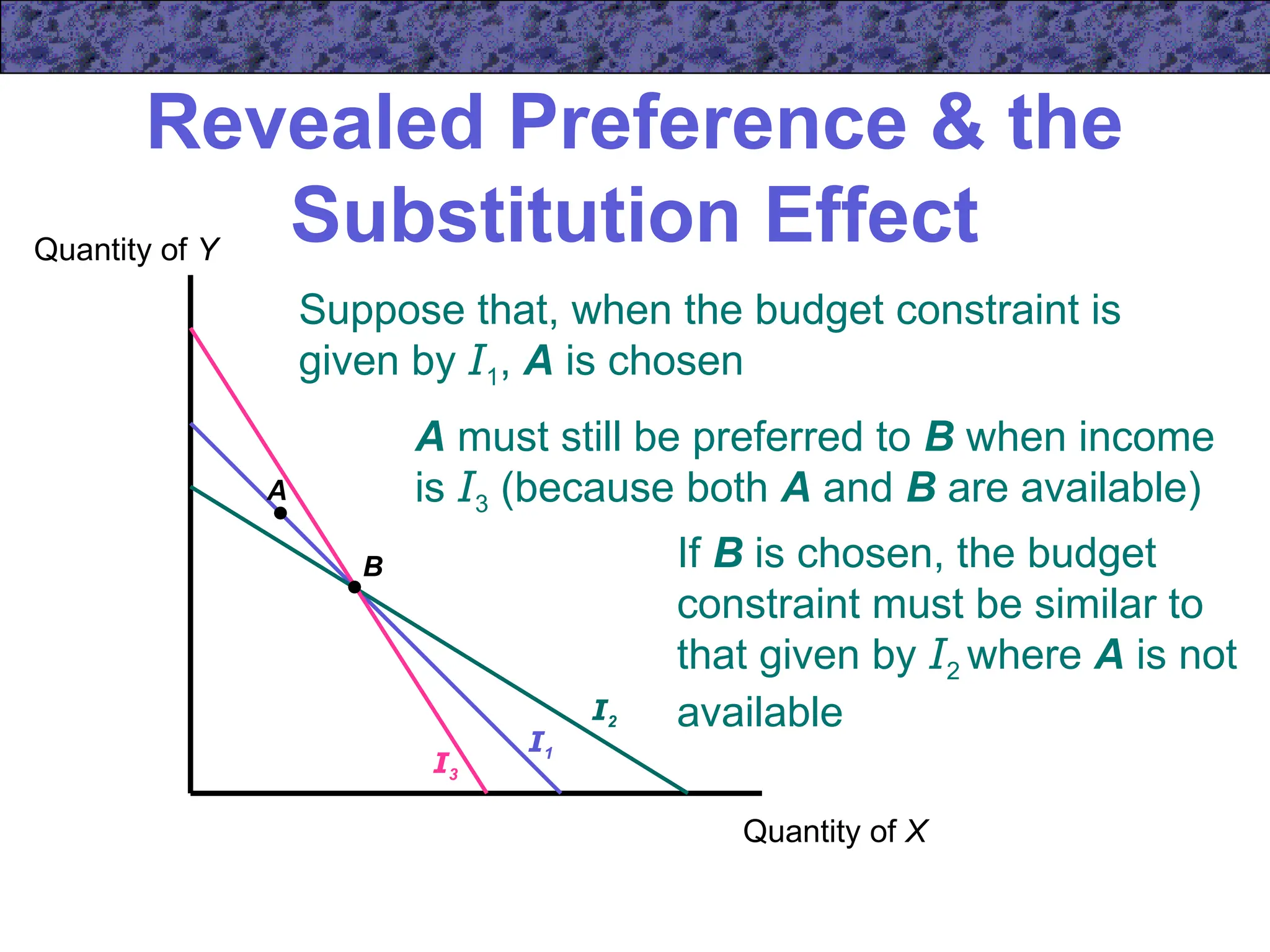

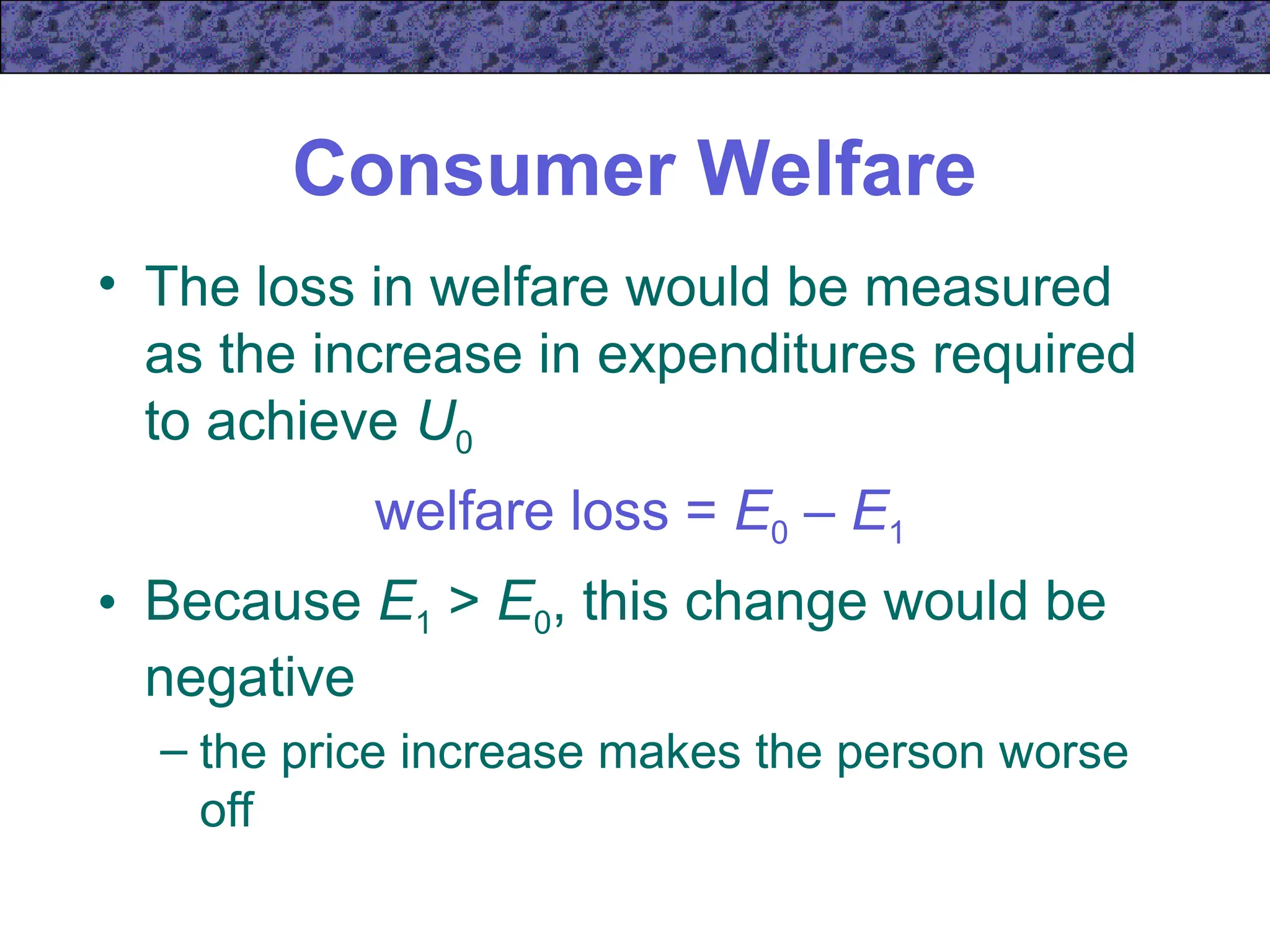

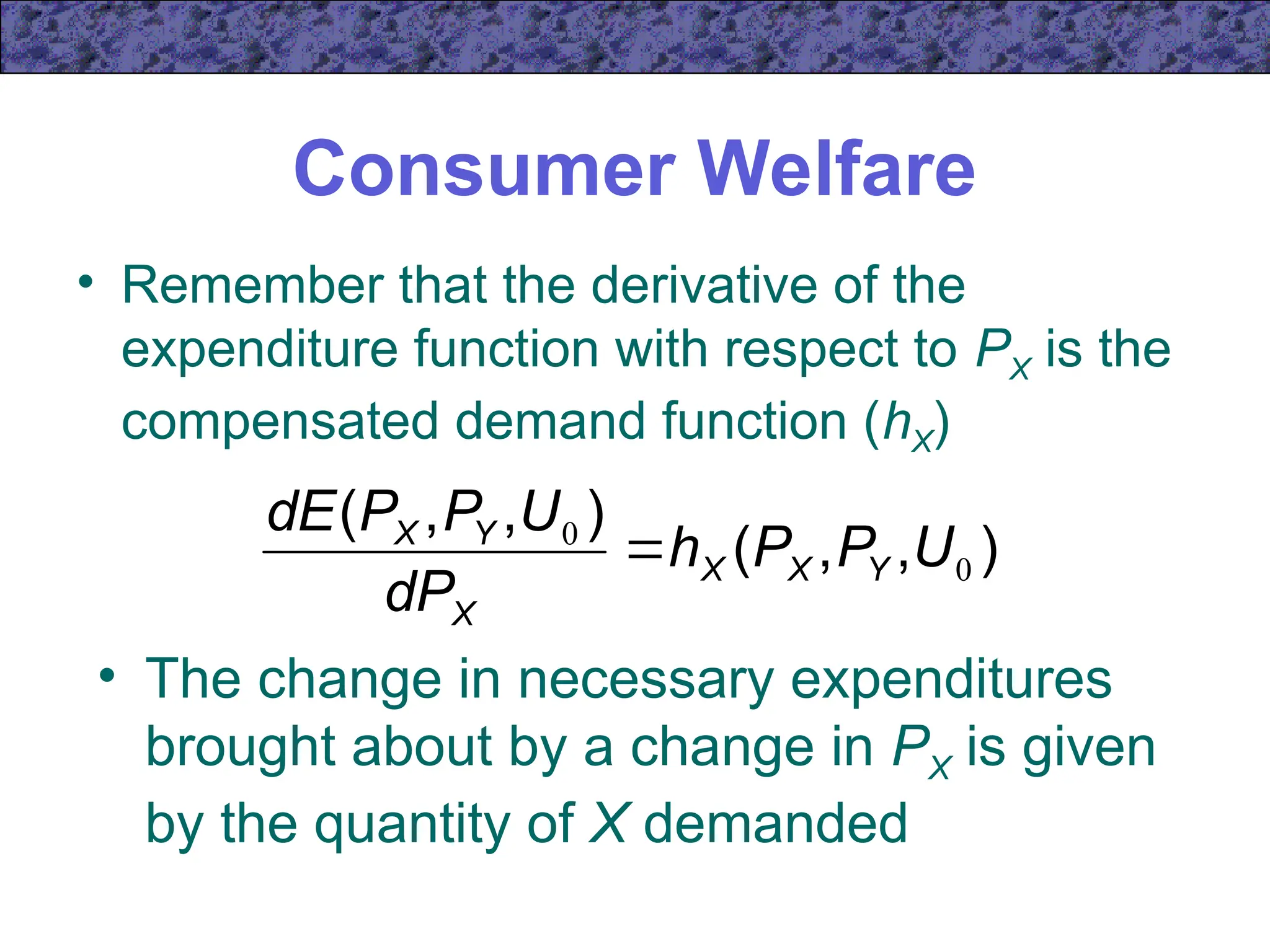

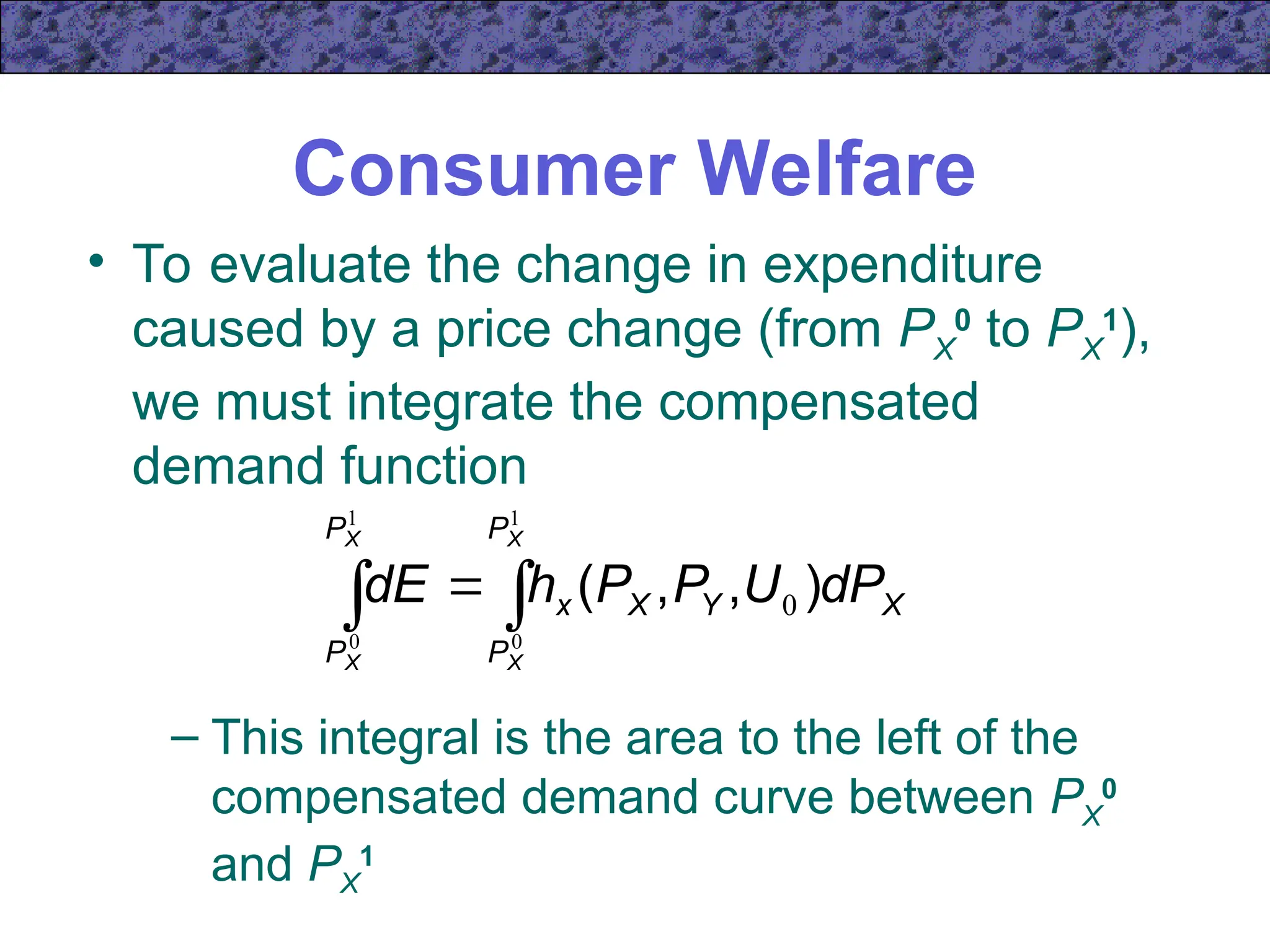

Chapter 5 focuses on income and substitution effects in microeconomic theory, detailing how changes in income and prices alter consumer behavior and demand functions. It introduces key concepts such as normal and inferior goods, Engel's Law, and the substitution and income effects during price changes. The chapter also covers demand curves, compensated demand functions, and the Slutsky equation, highlighting how consumer choices vary as prices and incomes fluctuate.

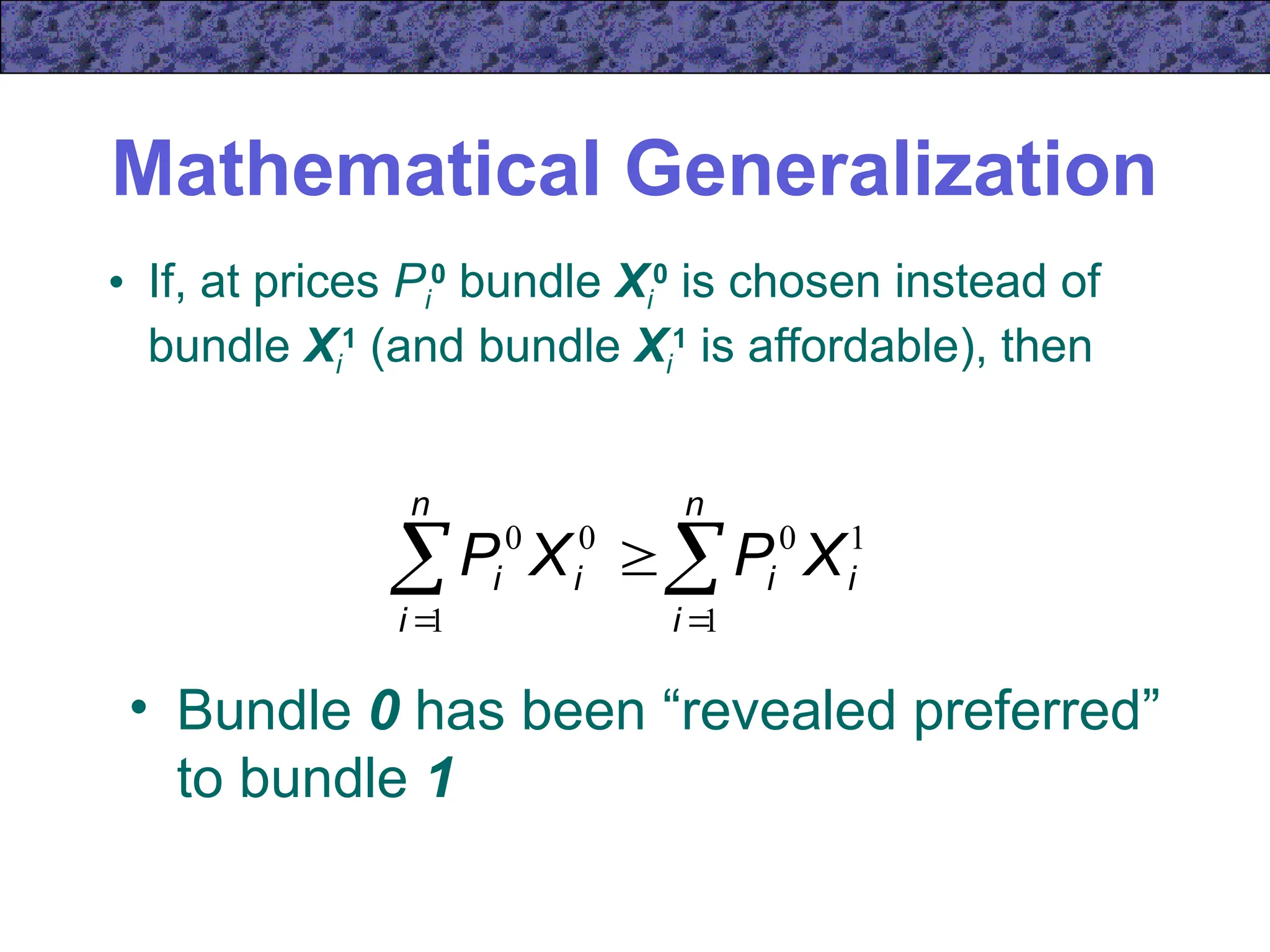

![A Mathematical Examination

of a Change in Price

• Instead, we will use an indirect approach

• Remember the expenditure function

minimum expenditure = E(PX,PY,U)

• Then, by definition

hX (PX,PY,U) = dX [PX,PY,E(PX,PY,U)]

– Note that the two demand functions are equal

when income is exactly what is needed to attain

the required utility level](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-241031060116-453d1aaa/75/ecn5402-ch05-ppt-lecture-note-income-and-substitution-effect-40-2048.jpg)

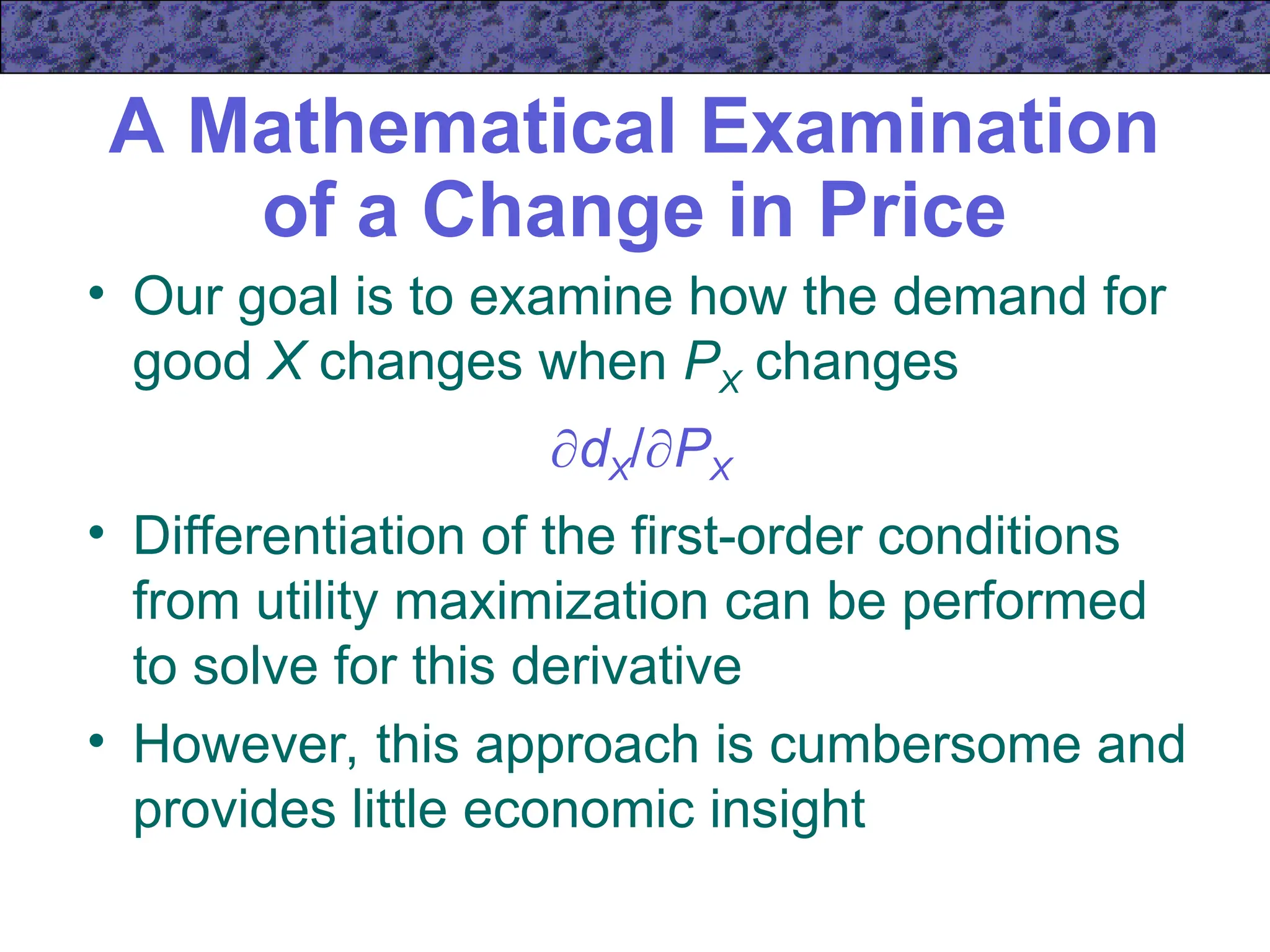

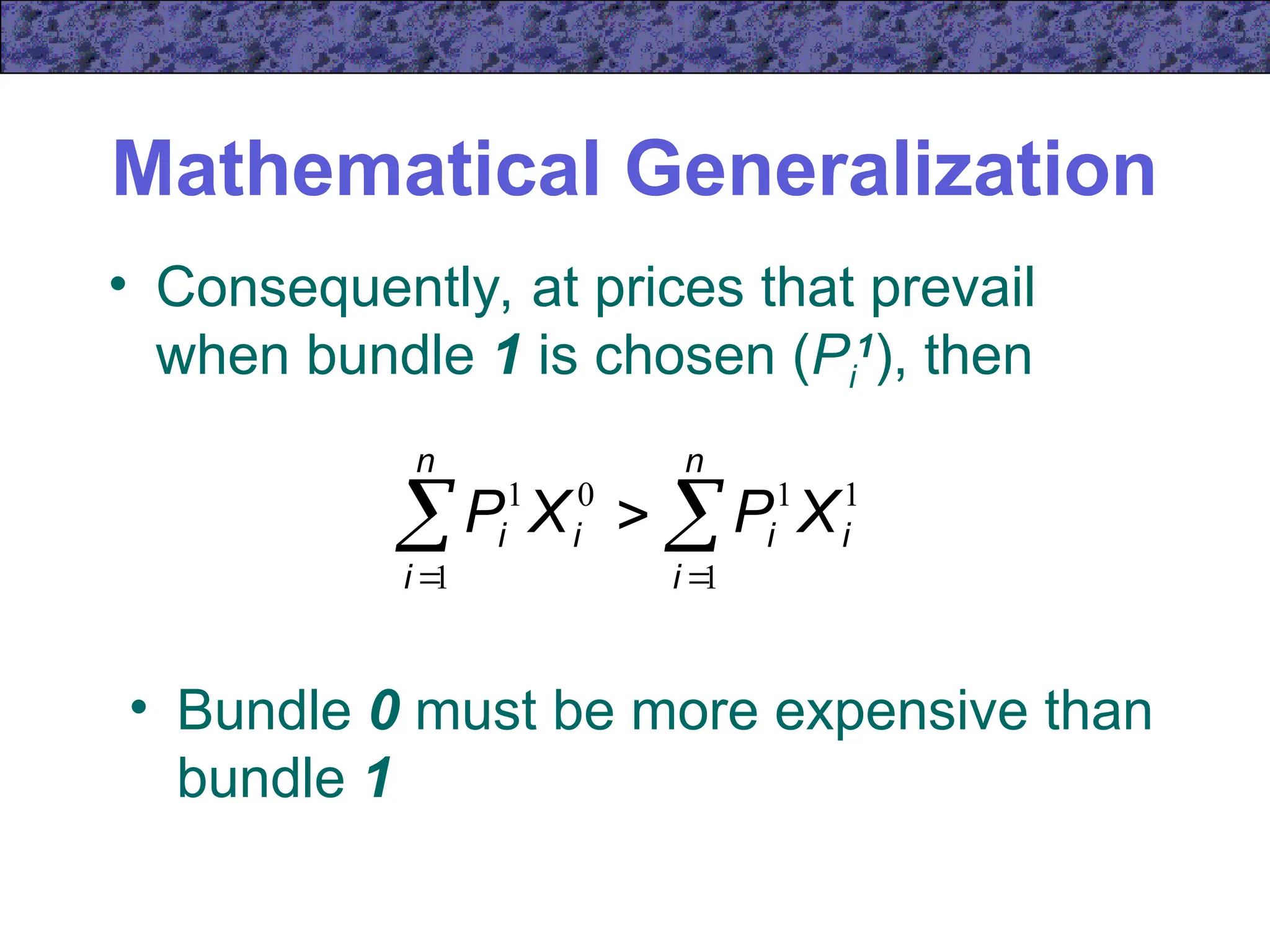

![A Mathematical Examination

of a Change in Price

• We can differentiate the compensated

demand function and get

hX (PX,PY,U) = dX [PX,PY,E(PX,PY,U)]

X

X

X

X

X

X

P

E

E

d

P

d

P

h

X

X

X

X

X

X

P

E

E

d

P

h

P

d

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-241031060116-453d1aaa/75/ecn5402-ch05-ppt-lecture-note-income-and-substitution-effect-41-2048.jpg)

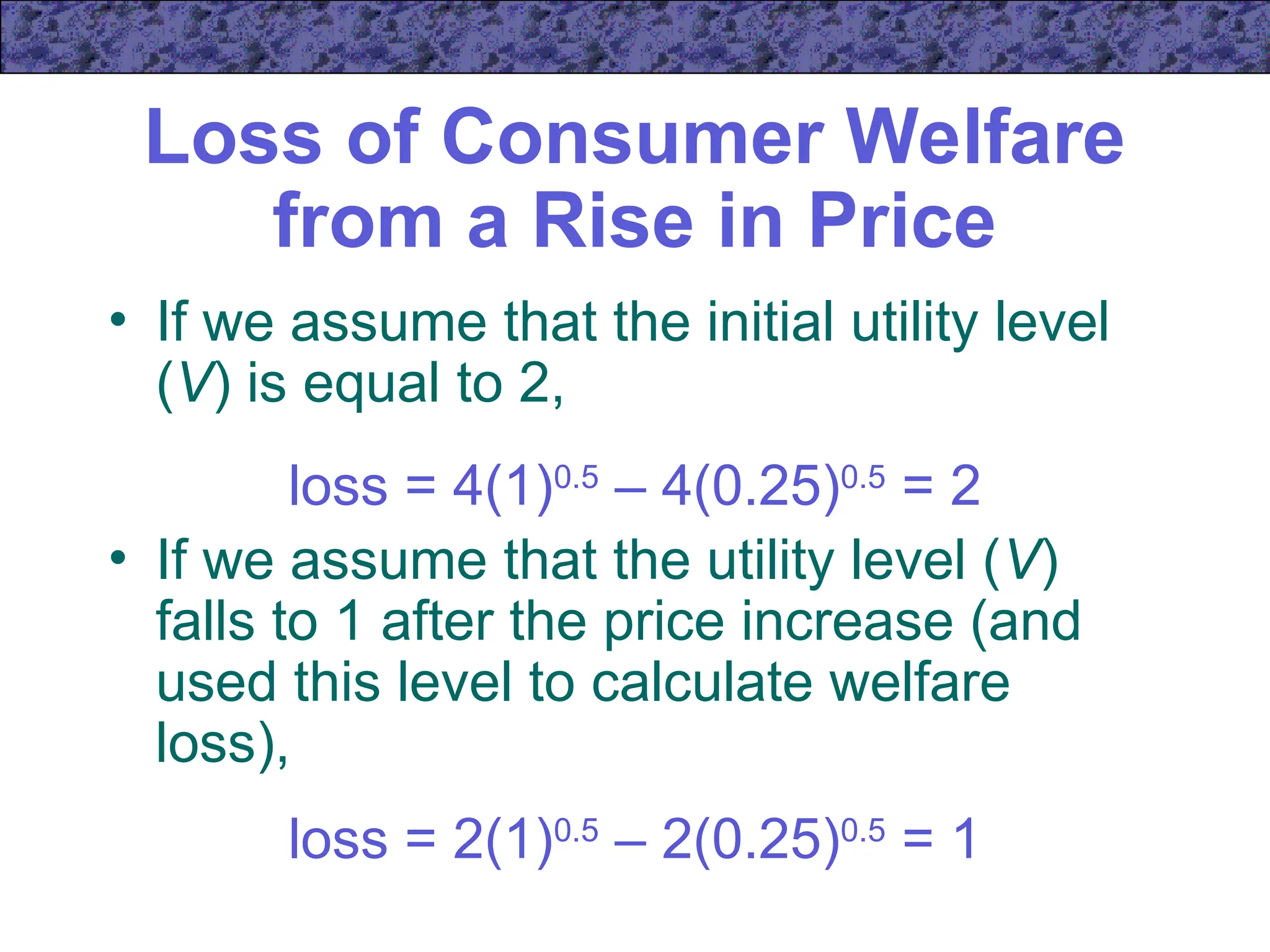

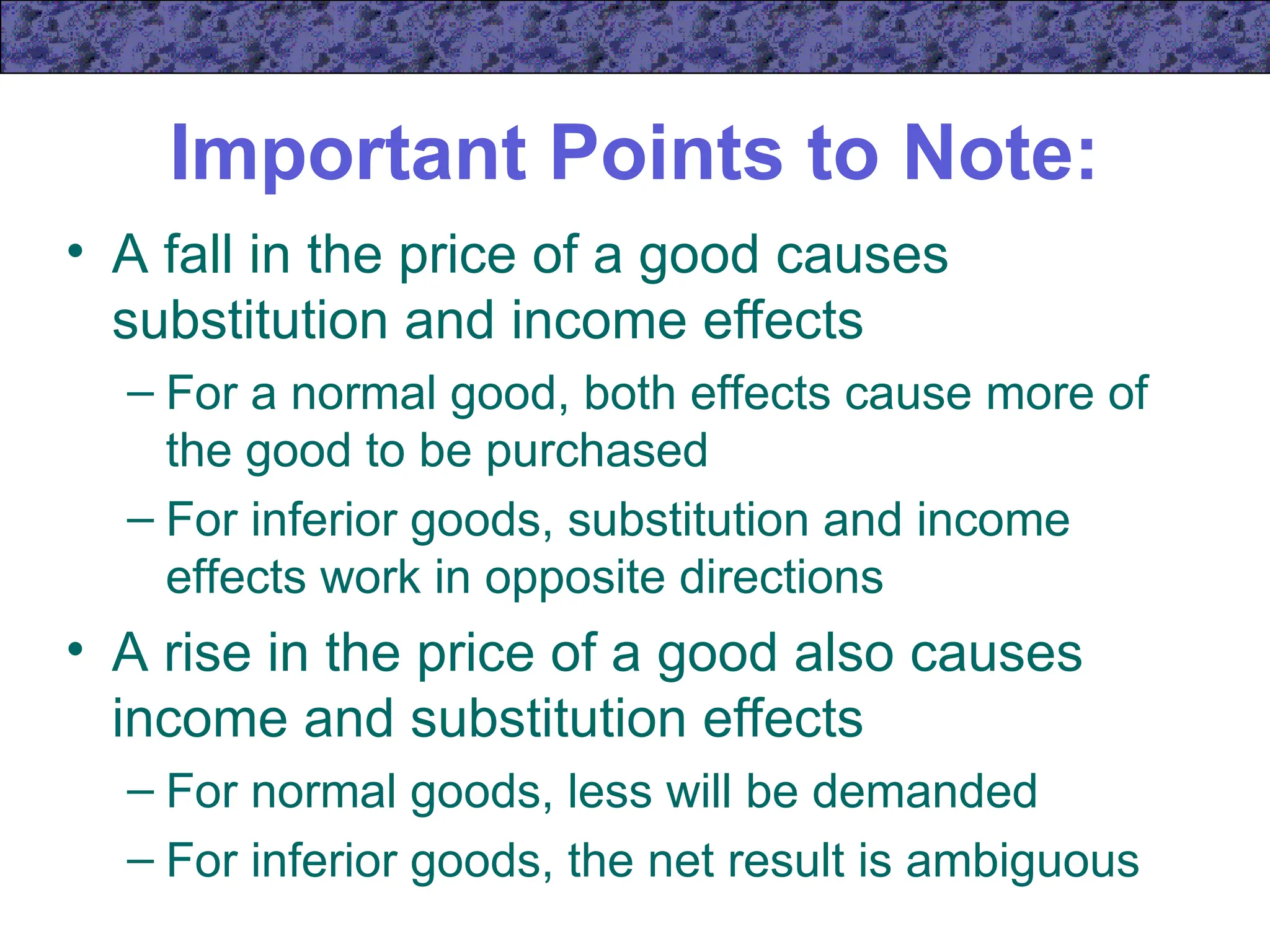

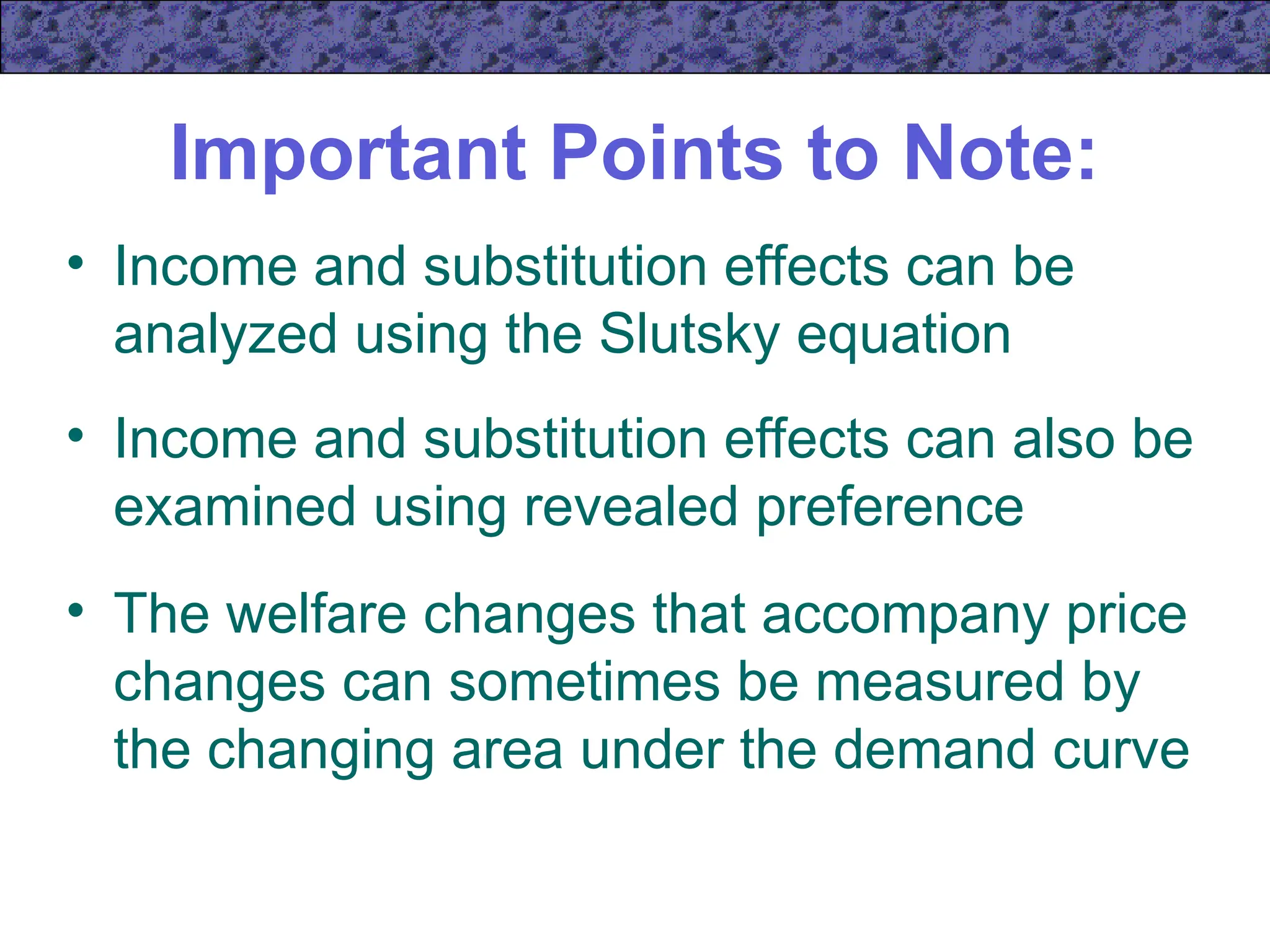

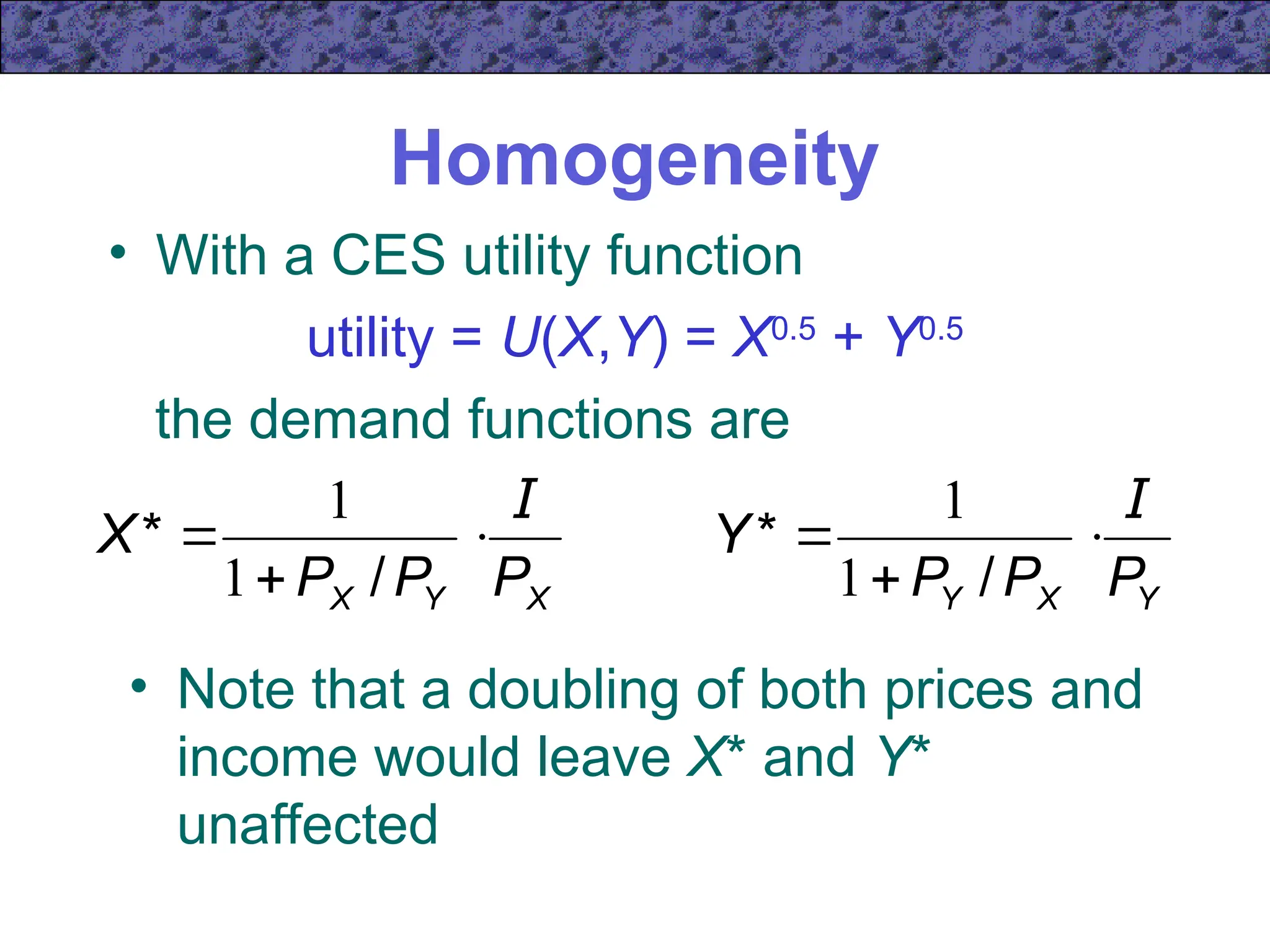

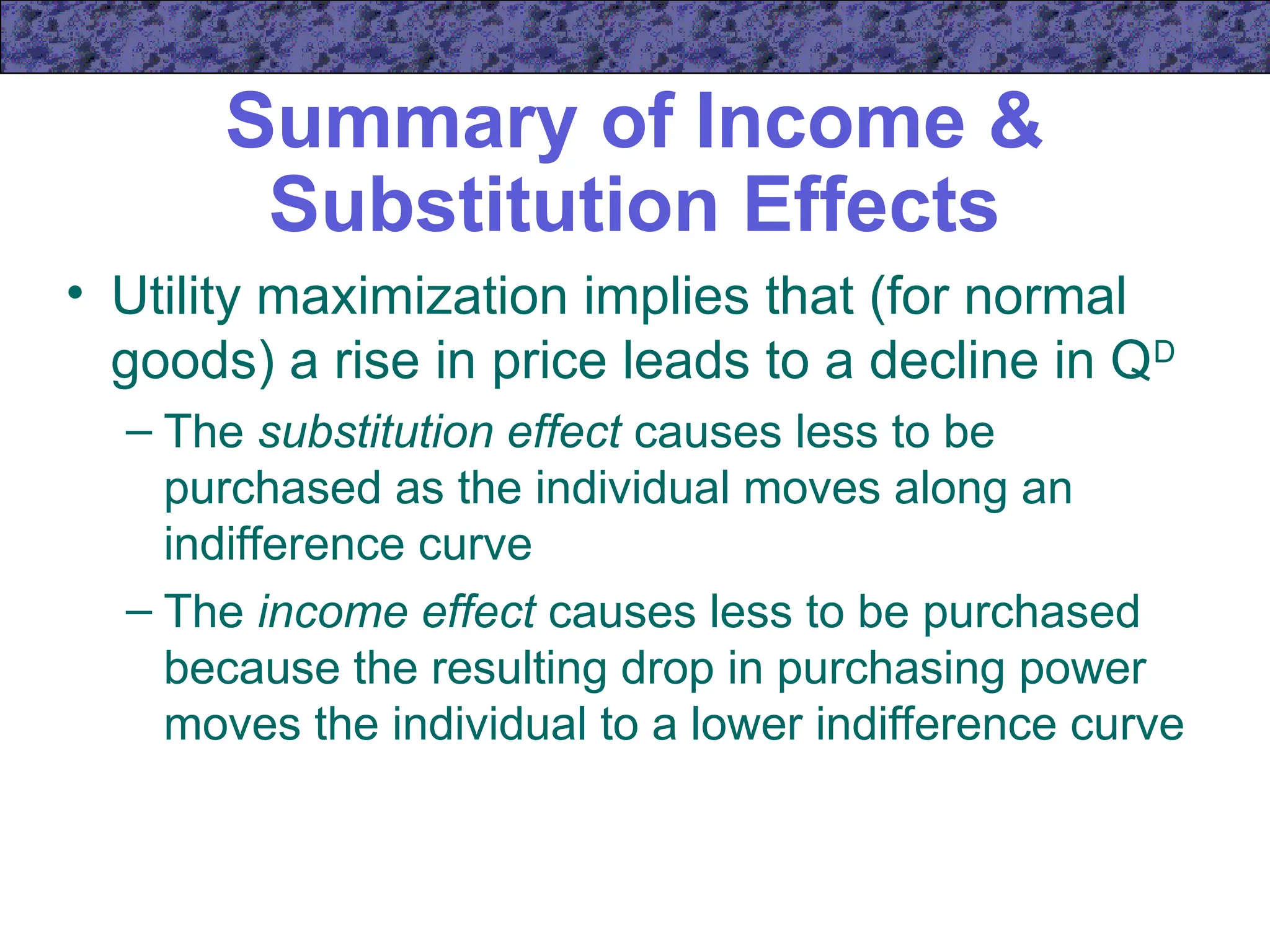

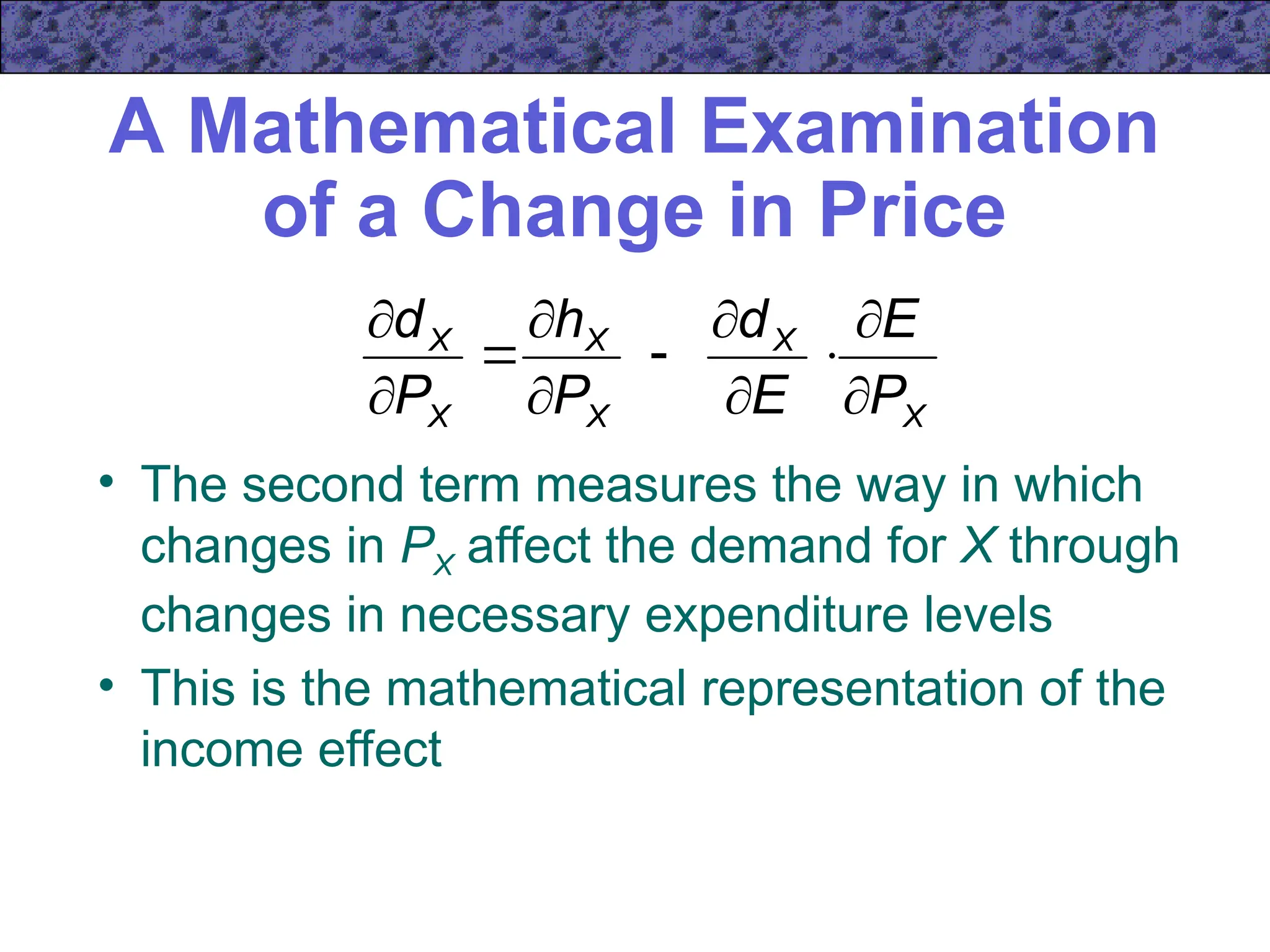

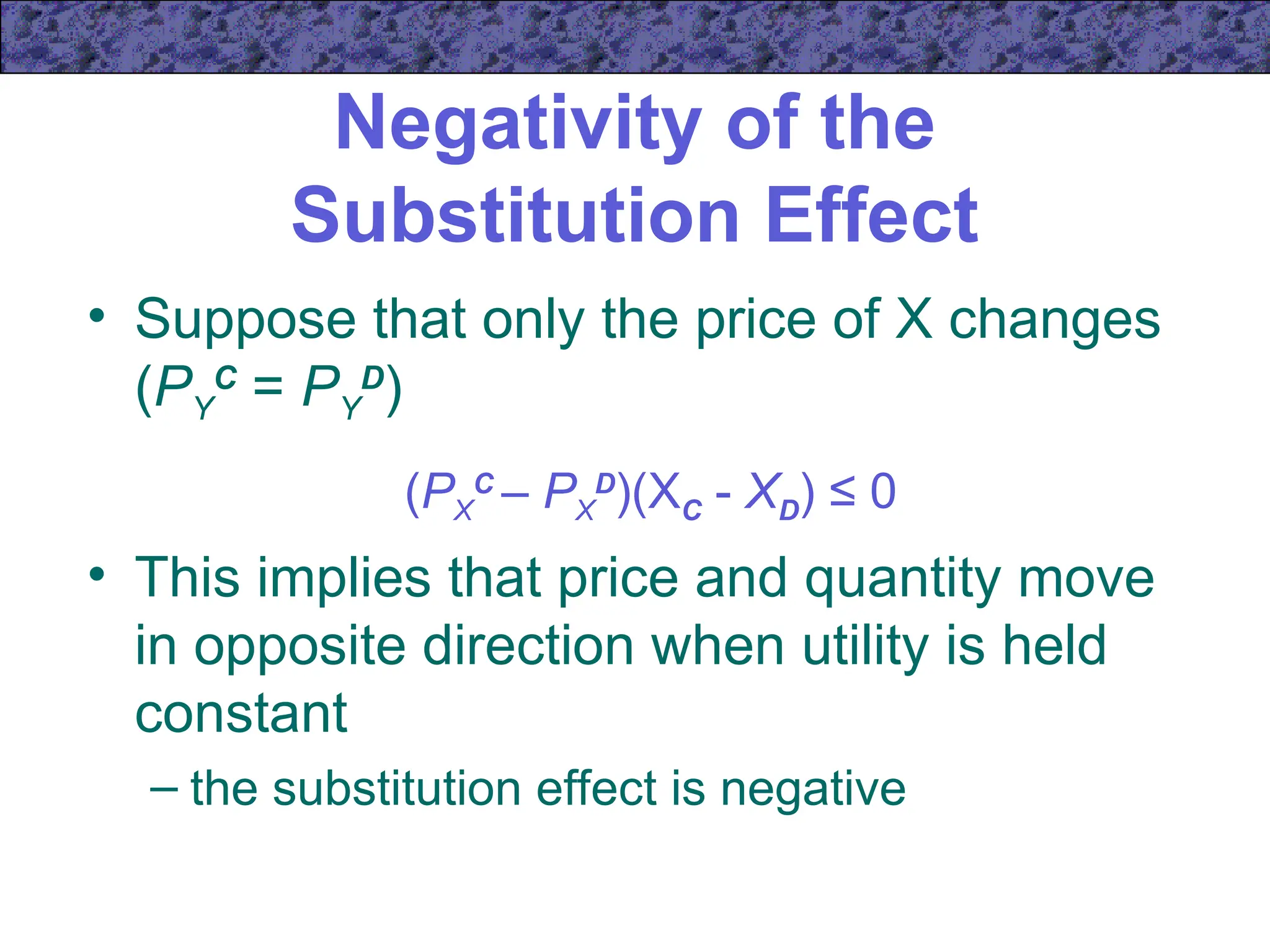

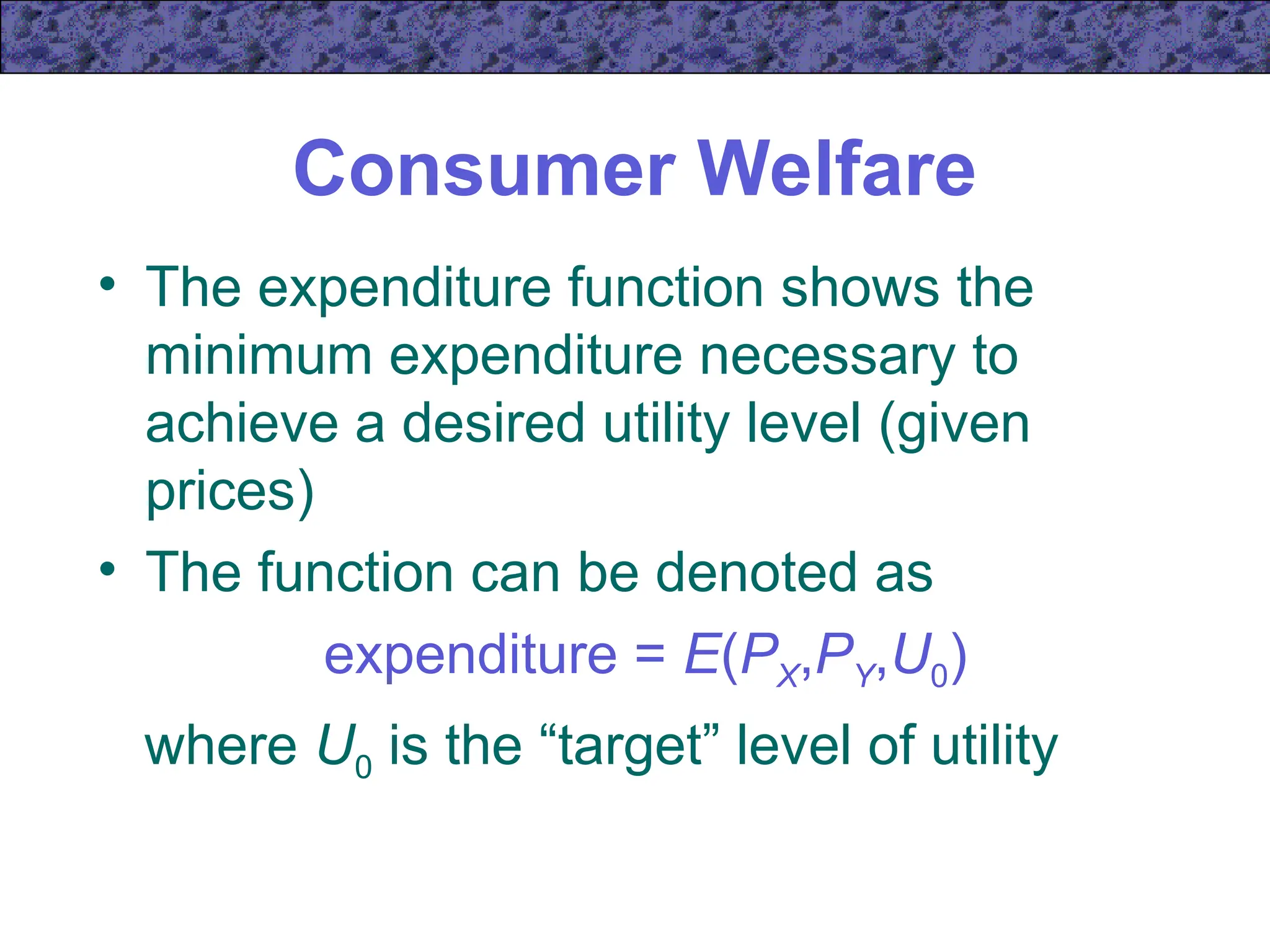

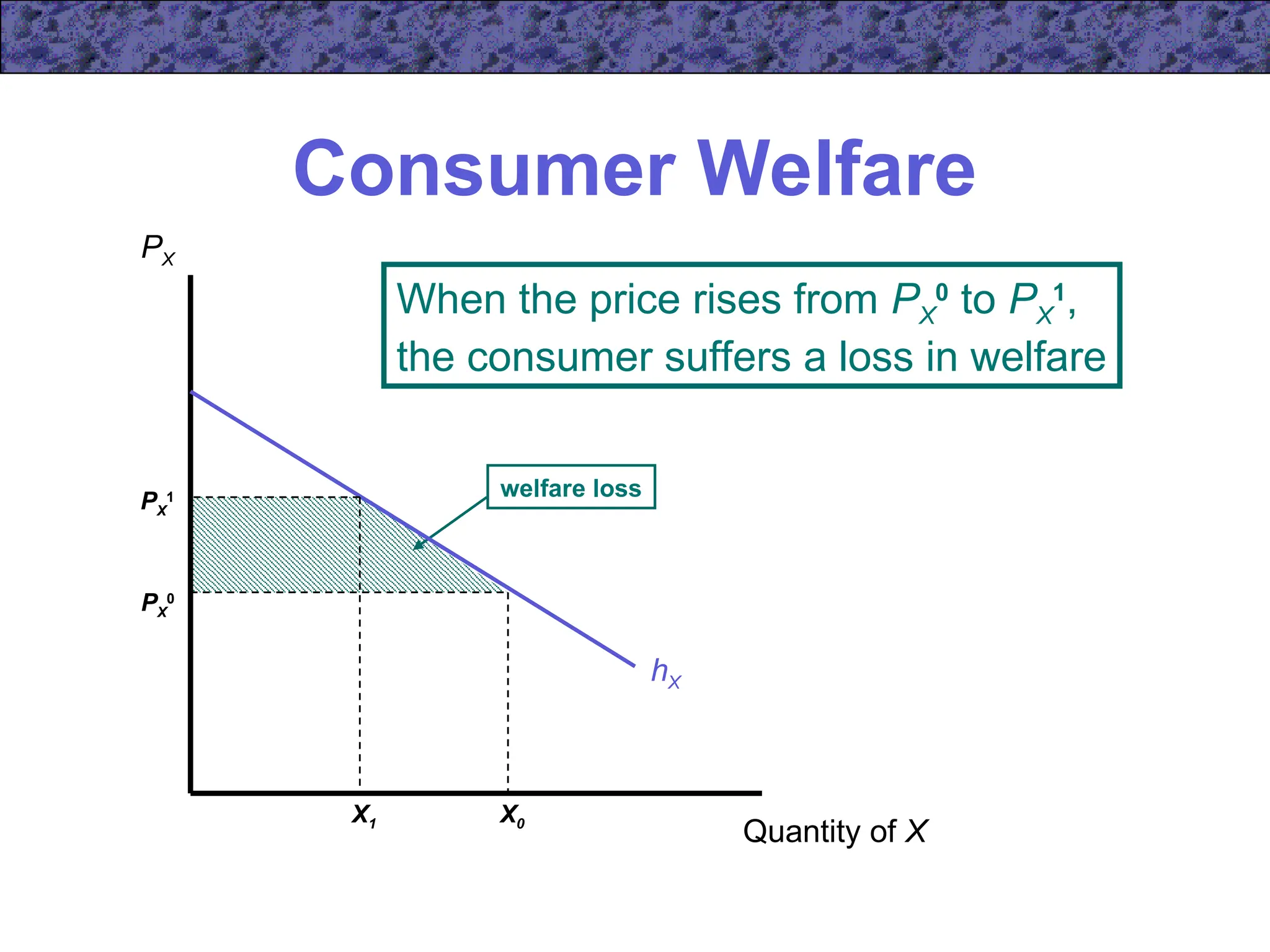

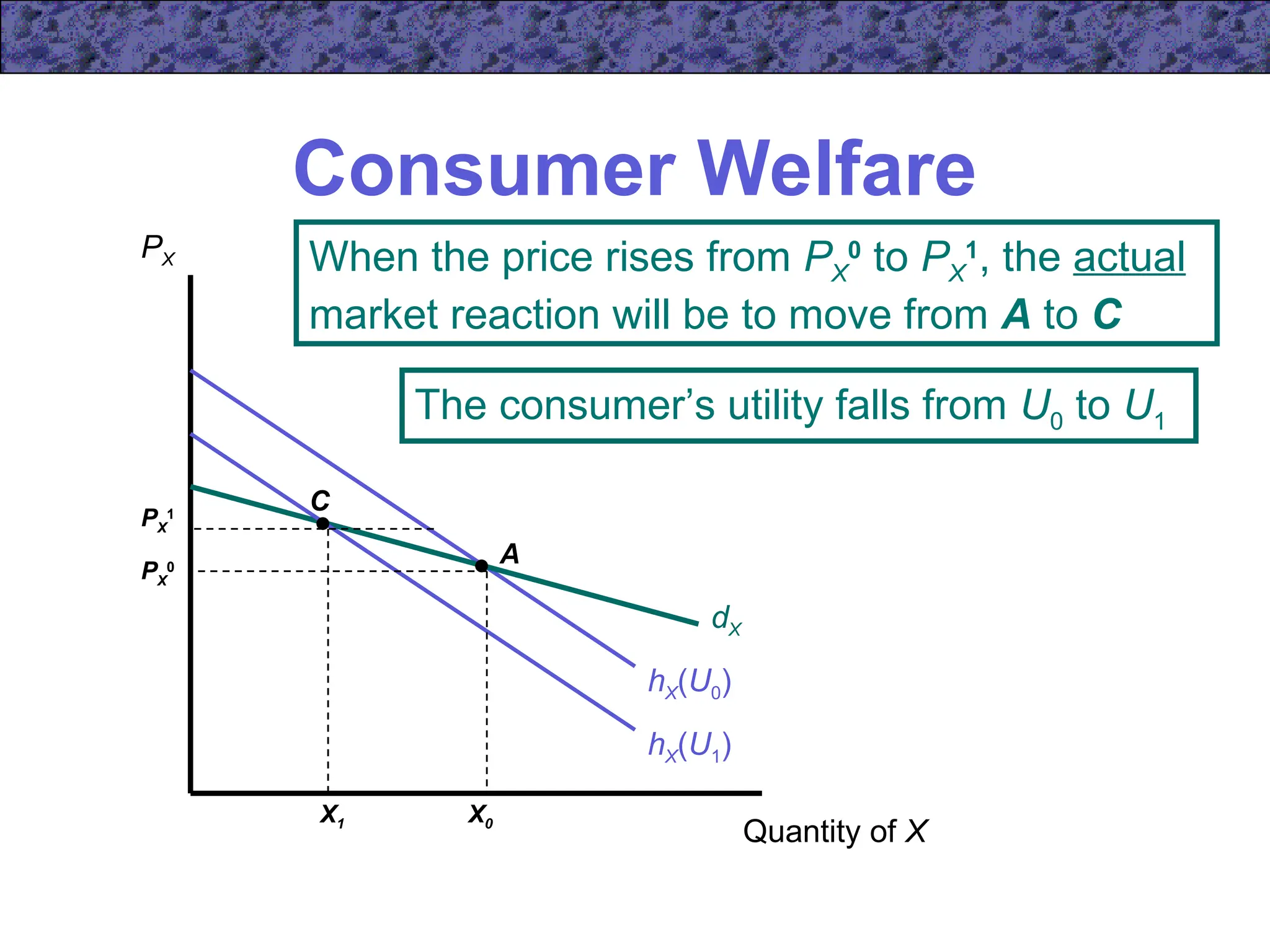

![Consumer Welfare

Quantity of X

PX

hX(U0)

PX

1

X1

Is the consumer’s loss in welfare best

described by area PX

1

BAPX

0

[using hX(U0)]

or by area PX

1

CDPX

0

[using hX(U1)]?

hX(U1)

dX

A

B

C

D

PX

0

X0

Is U0 or U1 the appropriate

utility target?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecn5402-241031060116-453d1aaa/75/ecn5402-ch05-ppt-lecture-note-income-and-substitution-effect-67-2048.jpg)