eeeeeeeebfffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkk

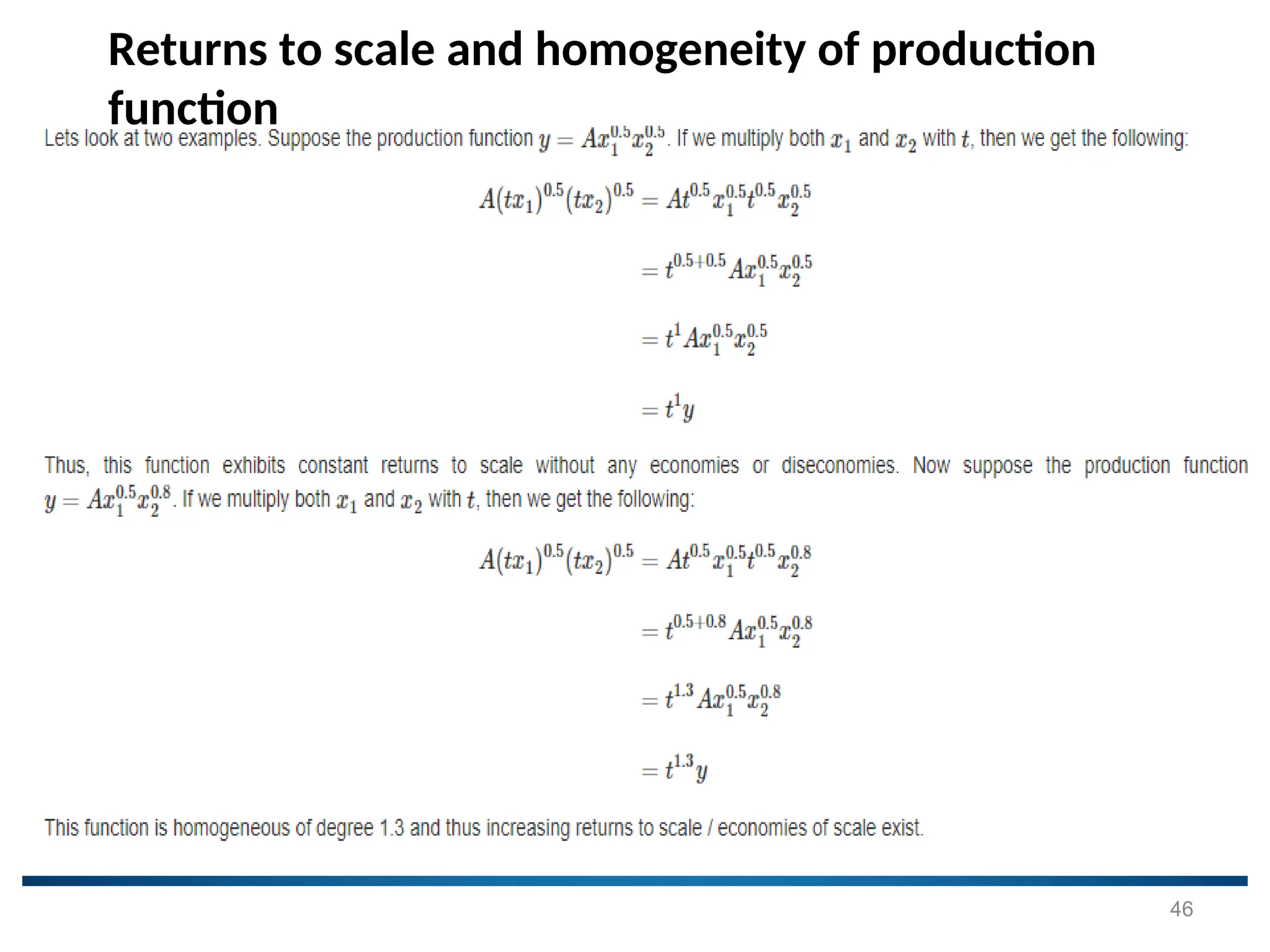

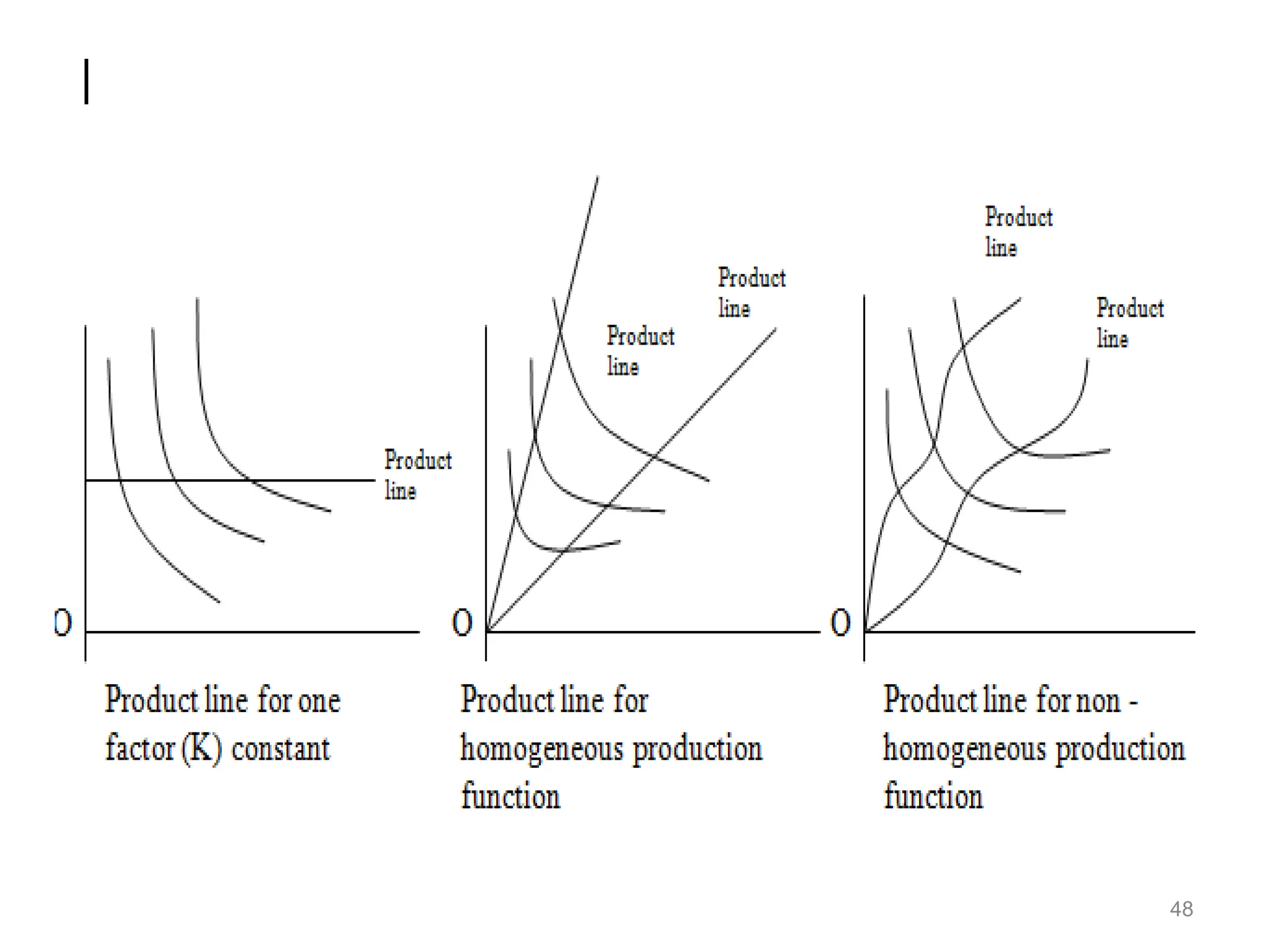

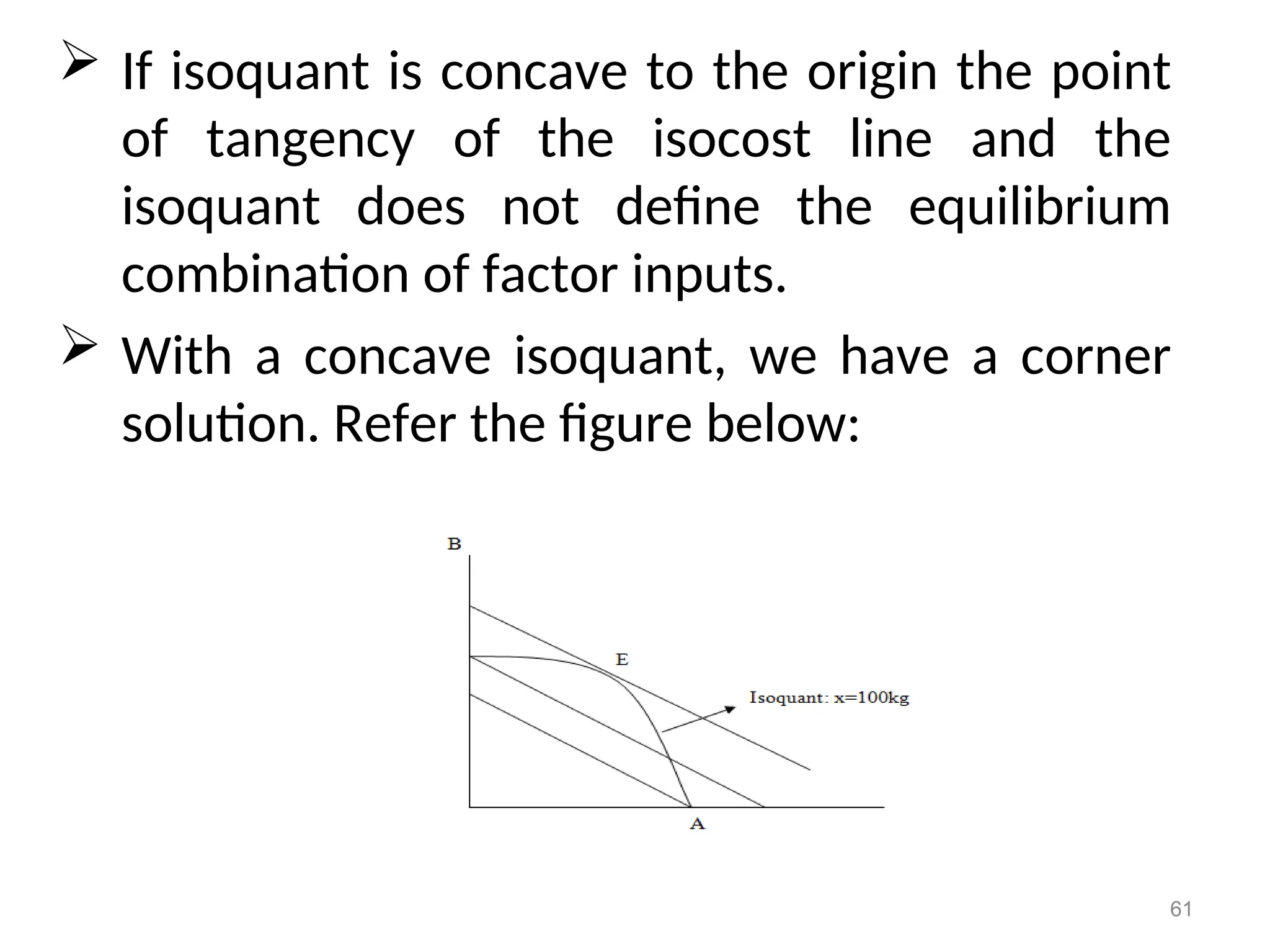

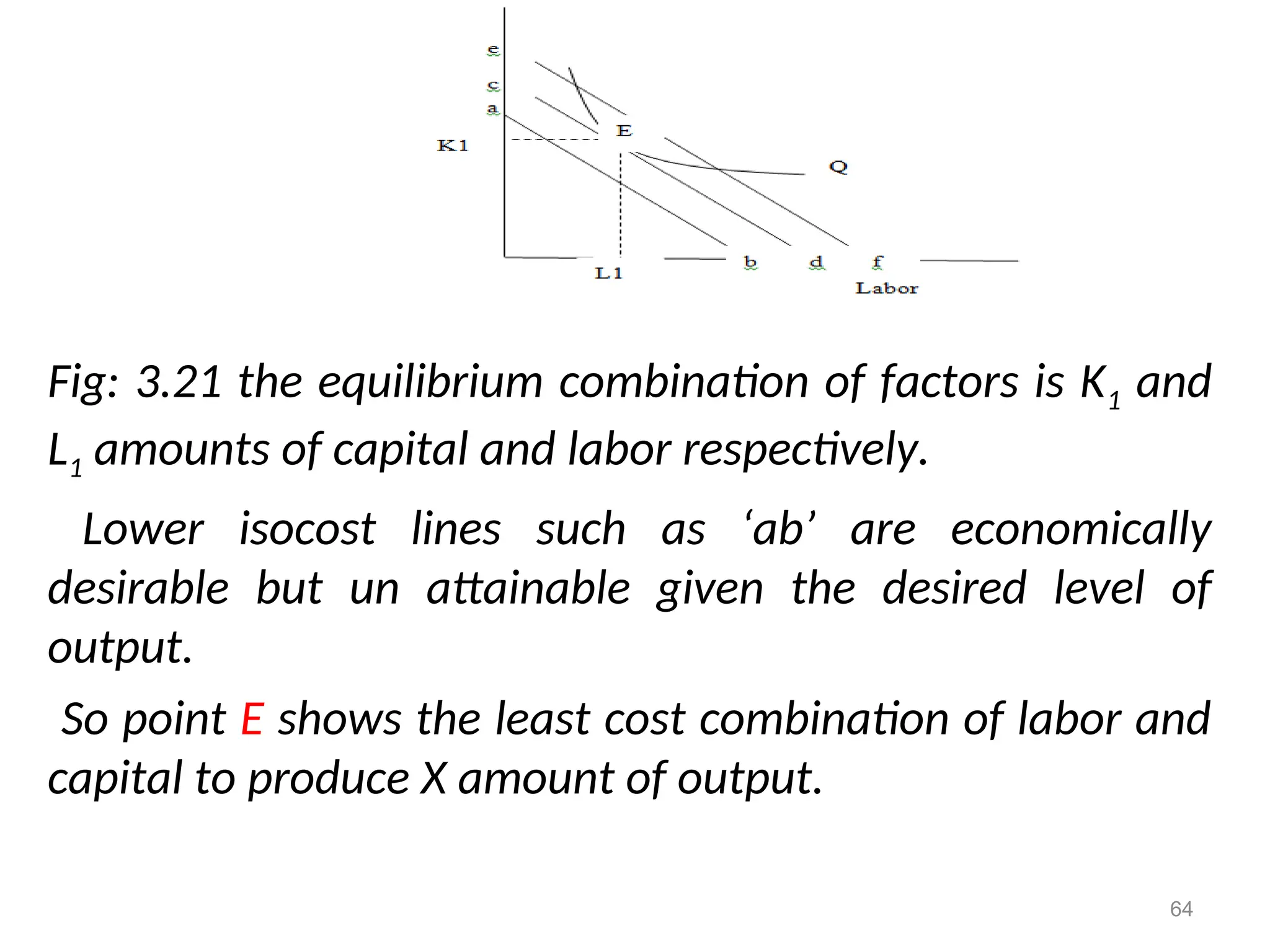

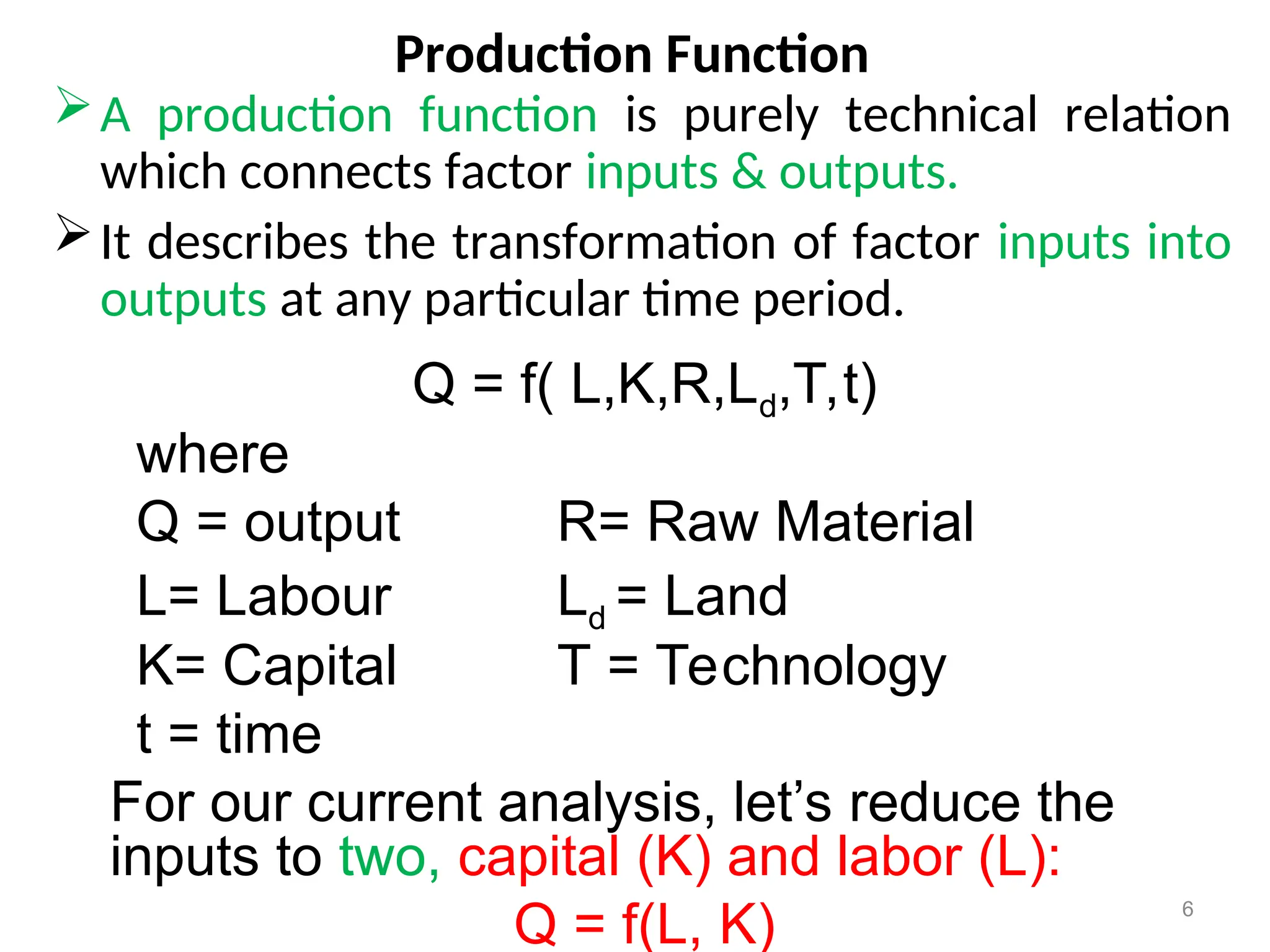

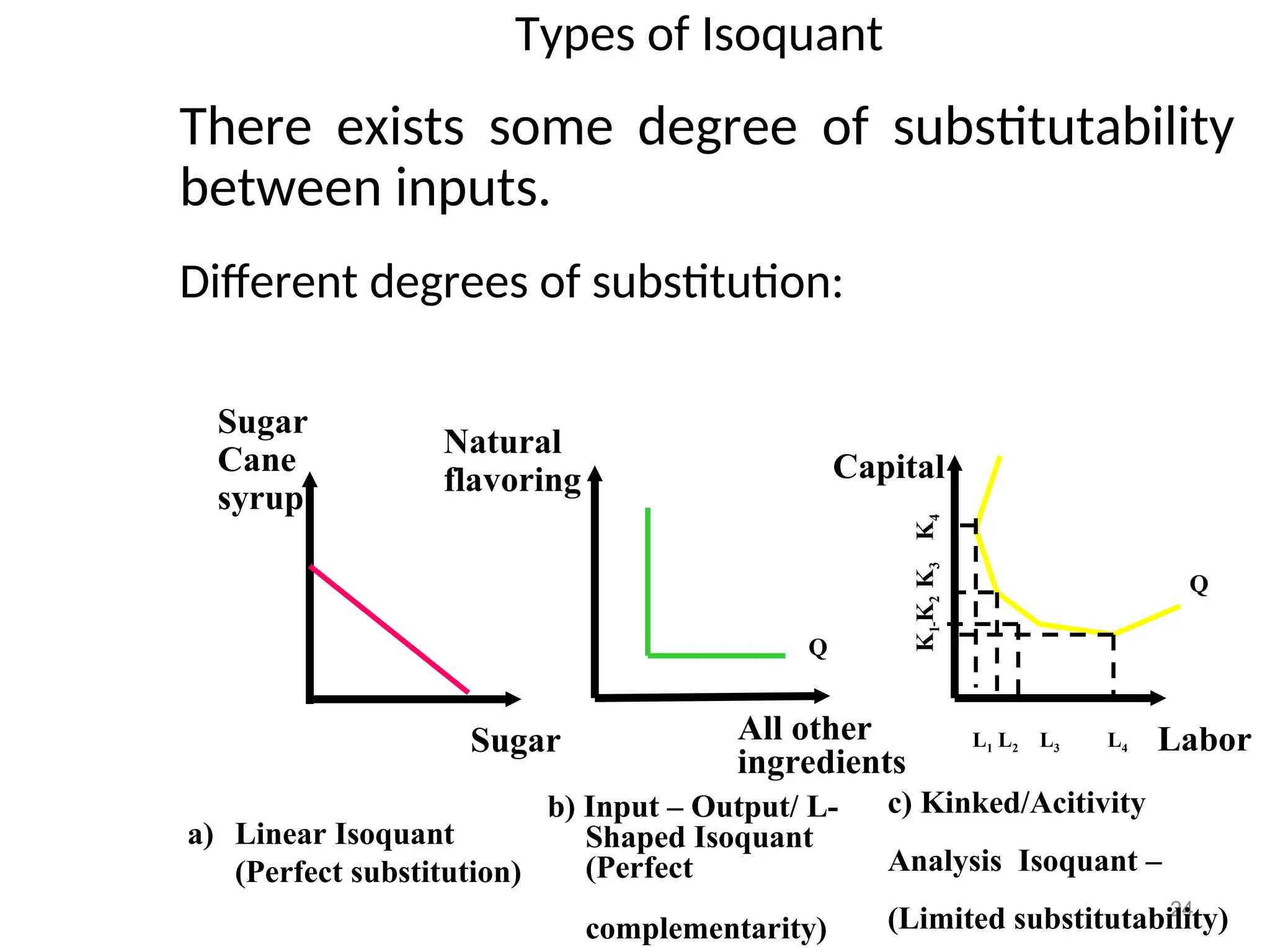

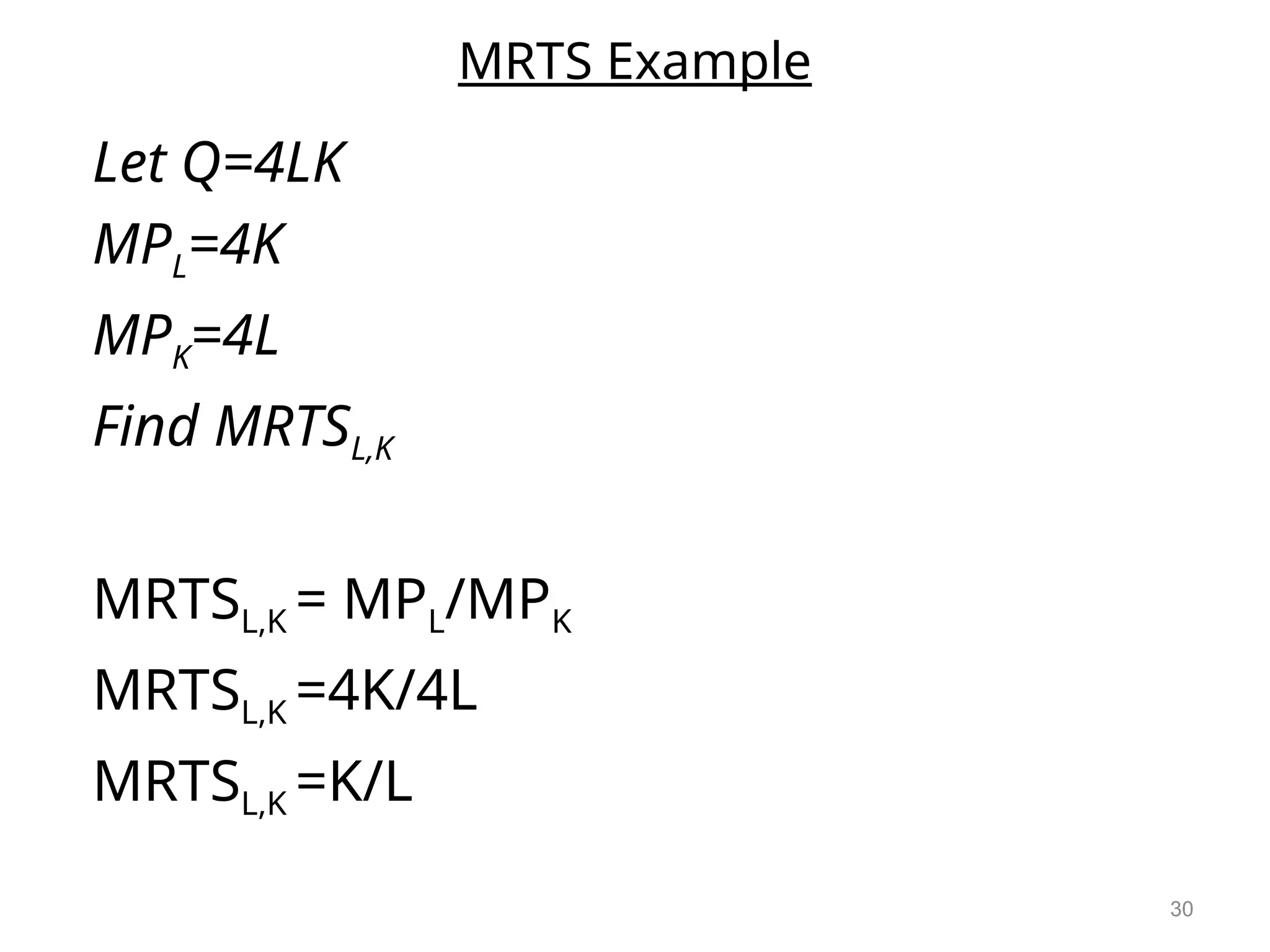

![How much will output increase when ALL inputs

increase by a particular amount?

RTS = [%Q] / [%(all inputs)]

1% increase in inputs => more than 1% increase in

output, increasing returns to scale.

1% increase in inputs => 1% increase in output

constant returns to scale.

1% increase in inputs => a less than 1% increase in

output, decreasing returns to scale.

31

Laws of Returns to Scale](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch3productiontheory-250413090312-029ba7ca/75/CHapter-production-theory-of-mco-eco-ppt-31-2048.jpg)