Chapter 7 focuses on thinking and intelligence, exploring key aspects of cognition such as perception, language, problem solving, and the nature of intelligence. It discusses the organization of thoughts through concepts and schemata, how natural and artificial concepts shape our understanding, and the development of language as a distinctive feature of human communication. The chapter ultimately aims to enhance appreciation for the high-level cognitive processes that define human consciousness.

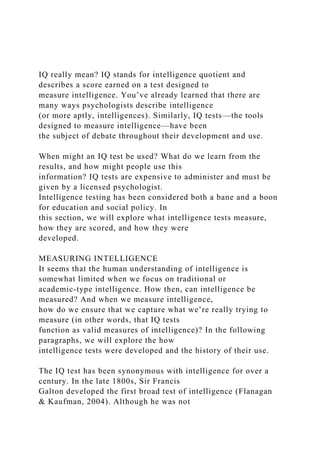

![Figure 7.14 Are you of below-average, average, or above-

average height?

The same principles apply to intelligence tests scores.

Individuals earn a score called an intelligence

quotient (IQ). Over the years, different types of IQ tests have

evolved, but the way scores are interpreted

remains the same. The average IQ score on an IQ test is 100.

Standard deviations describe how data are

dispersed in a population and give context to large data sets.

The bell curve uses the standard deviation

to show how all scores are dispersed from the average score

(Figure 7.15). In modern IQ testing, one

standard deviation is 15 points. So a score of 85 would be

described as “one standard deviation below

the mean.” How would you describe a score of 115 and a score

of 70? Any IQ score that falls within one

standard deviation above and below the mean (between 85 and

115) is considered average, and 68% of the

population has IQ scores in this range. An IQ score of 130 or

above is considered a superior level.

240 Chapter 7 | Thinking and Intelligence

This OpenStax book is available for free at

https://cnx.org/content/col11629/1.5

Figure 7.15 The majority of people have an IQ score between 85

and 115.

Only 2.2% of the population has an IQ score below 70

(American Psychological Association [APA], 2013).

A score of 70 or below indicates significant cognitive delays,

major deficits in adaptive functioning,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter7thinkingandintelligencefigure7-221025160232-51bd56d3/85/Chapter-7Thinking-and-IntelligenceFigure-7-1-Thinking-docx-49-320.jpg)

![Ashford University | BUS624 WEEK THREE | DISCUSSION

ONE

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Welcome to the week 3 Discussion One assignment. This week,

you get introduced to a very important legal topic-

- contracts. Additionally, we will further explore the topic of

ethics.

Regarding contracts, why is it such an important legal topic?

According to some legal theorists, contracts is the

single most important topic that is studied in law. Why? Some

say it underlies all the other major legal topics.

Constitutional law-- some philosophers have asserted that there

is a social contract between the government and

the governed. Property law-- much of property law revolves

around an agreement or understanding the society

has with real estate that you and I own. And there are many

other metaphors and examples from other legal

disciplines. From this fundamental perspective, contract is, in

essence, a legally enforceable agreement between

two parties.

The subject of the agreement involve and implicate many other

topics, so fundamentally, contracts is an important](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter7thinkingandintelligencefigure7-221025160232-51bd56d3/85/Chapter-7Thinking-and-IntelligenceFigure-7-1-Thinking-docx-81-320.jpg)