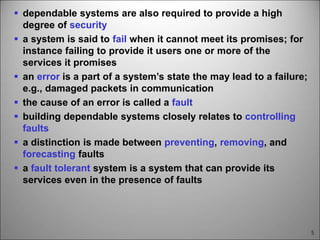

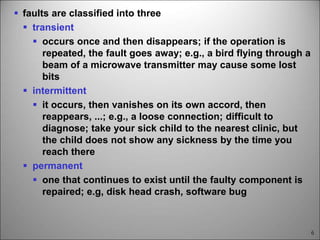

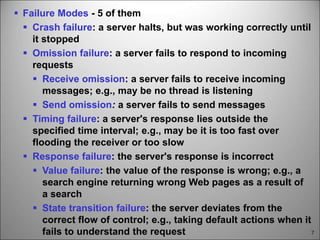

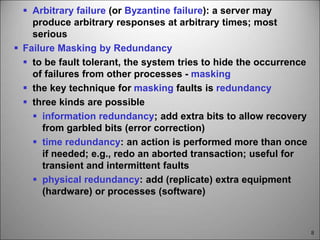

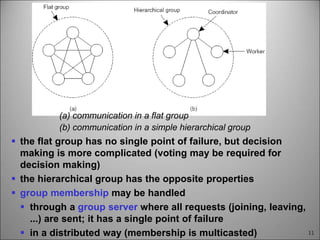

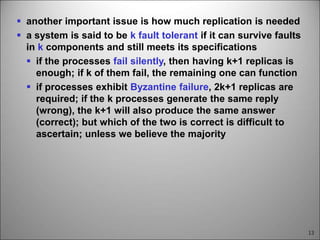

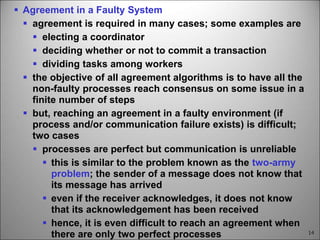

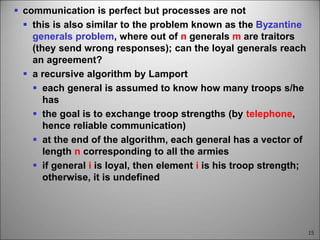

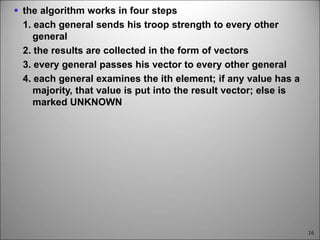

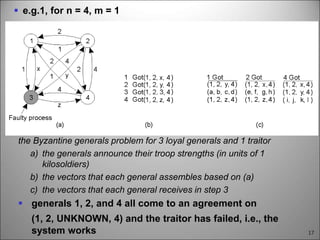

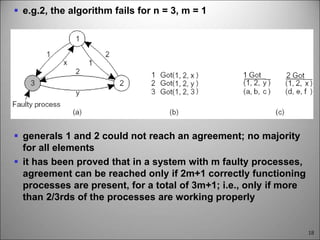

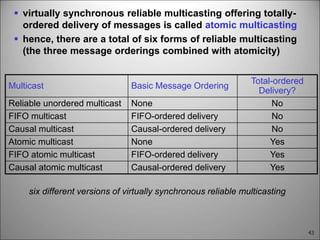

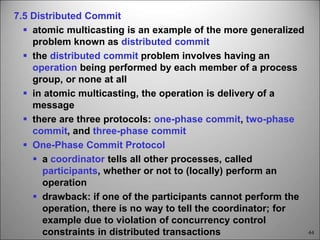

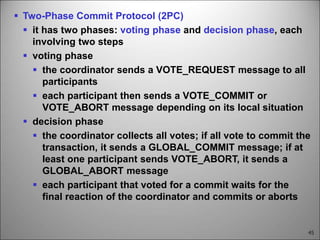

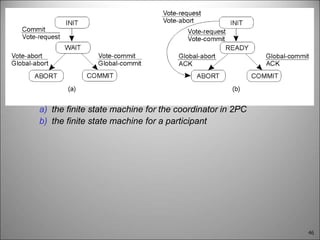

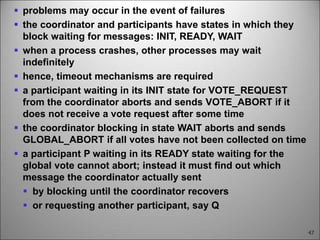

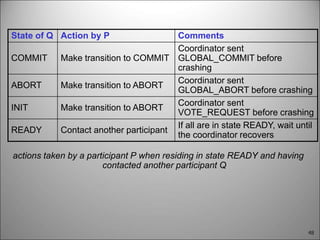

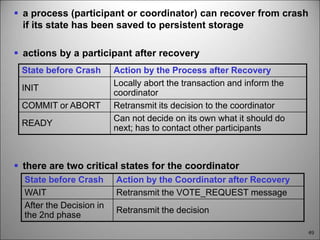

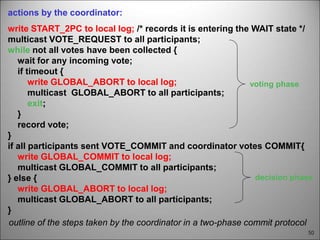

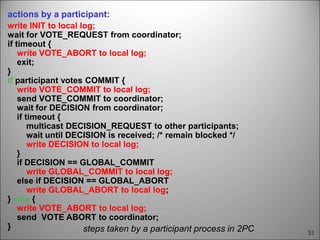

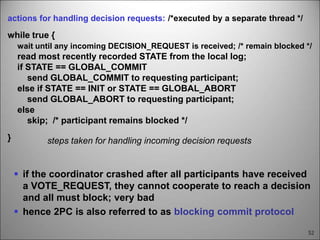

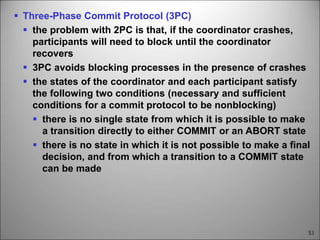

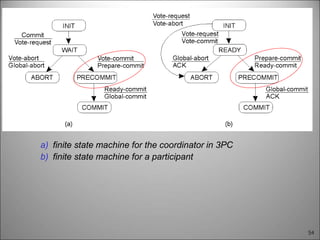

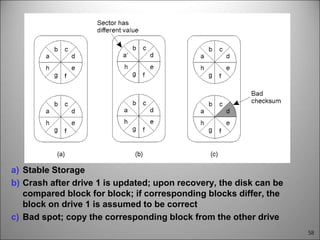

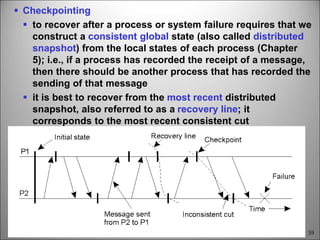

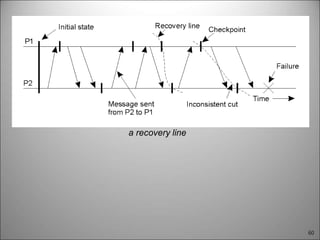

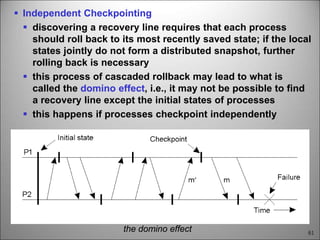

This chapter discusses fault tolerance in distributed systems. It covers process resilience through replicating processes into groups that can tolerate failures. It also discusses reliable multicasting to synchronize processes and distributed commit protocols for ensuring atomicity. The chapter objectives are to discuss these topics as well as failure recovery through state saving. It describes different types of faults, failure modes, and how redundancy can be used to mask faults.