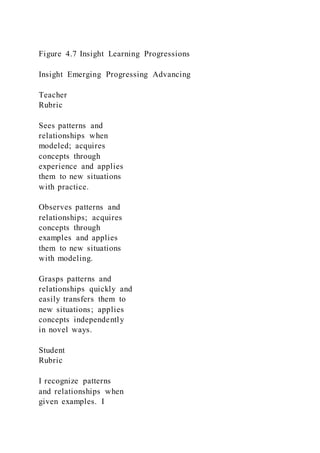

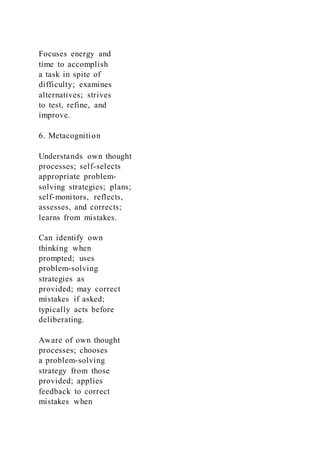

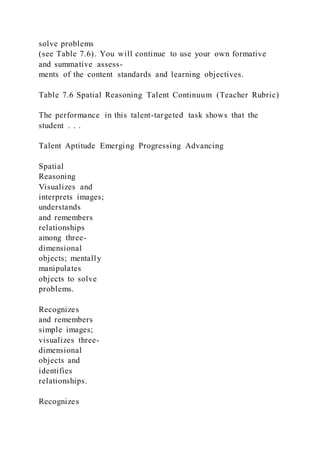

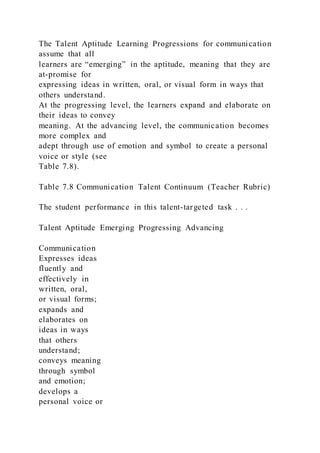

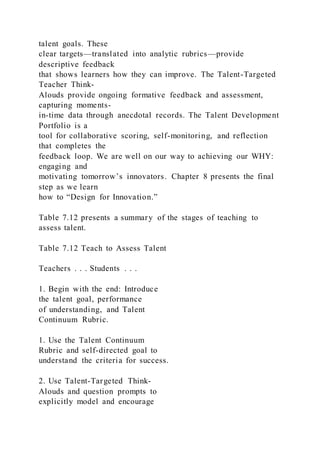

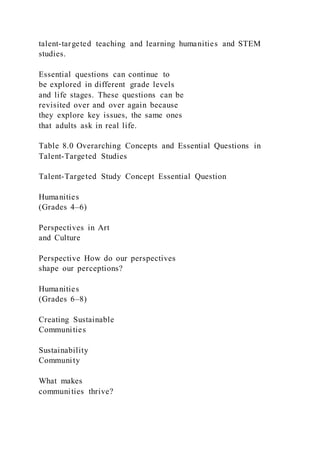

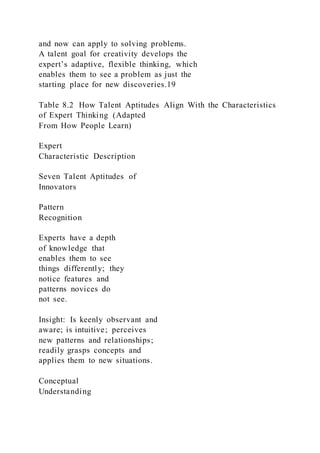

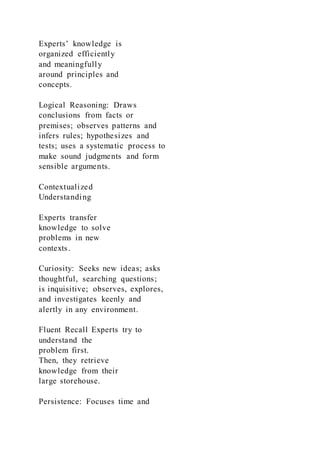

Chapter 7 focuses on the importance of formative assessment in developing student ownership of learning and utilizing analytic rubrics for talent assessment. It details assessment strategies such as structured observations and talent portfolios, emphasizing their role in empowering talent development. Chapter 8 presents design essentials for creating a curriculum aimed at fostering innovation, encouraging the use of differentiated lesson plans to cultivate students' aptitudes.

![can shift the focus

from short-term content knowledge and skill acquisition to

long-term aims for

talent development, the process by which learners gain content

expertise as they

develop their individual talent aptitudes.

We have measured achievement using standardized test scores

for so long that we

have lost sight of the long-term goals of education. Grant

Wiggins, co-creator of

the Understanding by Design (UbD) curriculum planning

framework, concludes

that regardless of what our 21st-century-

skills-focused mission statements proclaim,

“it is possible to get straight A’s at every

school in America without [developing]

critical and creative thinking.”1 If this is the

case, we are not equitably preparing all stu-

dents for the innovation economy. We need

to frame our goals around—plan, teach,

and assess—the aptitudes of innovators.

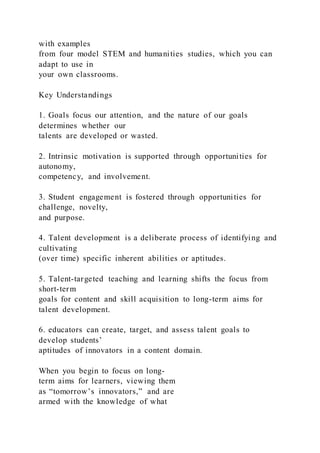

Key Understandings

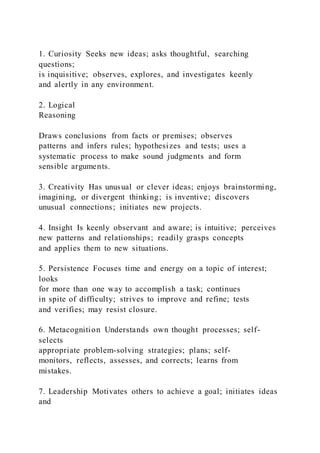

1. We can identify the aptitudes of innovators by studying their

real-life achieve-

ments that demonstrate their curiosity, logical reasoning,

creativity, insight, persis-

tence, metacognition, and leadership.

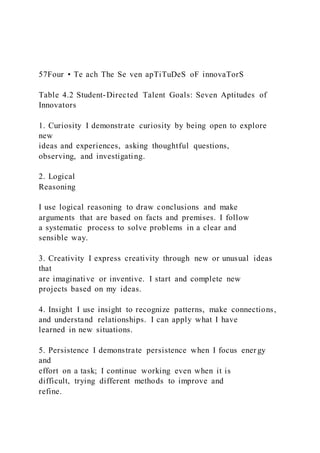

2. By explicitly creating goals to target these aptitudes, we

provide our students

with opportunities to discover and develop their unique talent

potential to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter7teachtoassesstalentthischapterdevelopssixke-220921134401-caa82c93/85/CHAPTER-7-TEACH-TO-ASSESS-TALENTThis-chapter-develops-six-Ke-112-320.jpg)