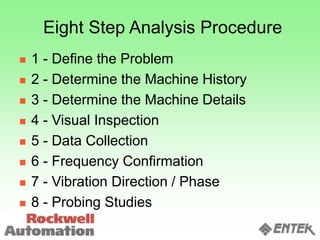

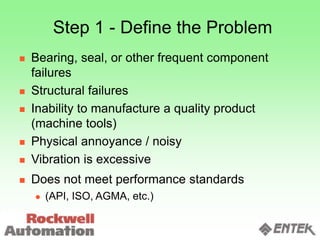

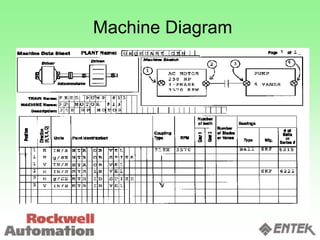

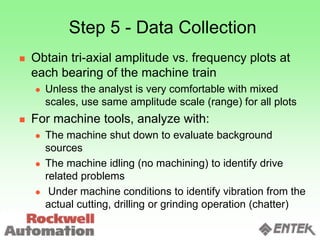

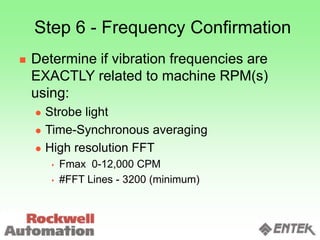

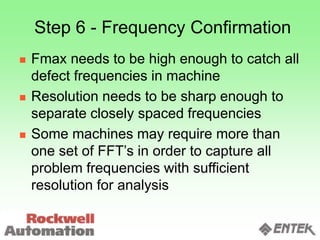

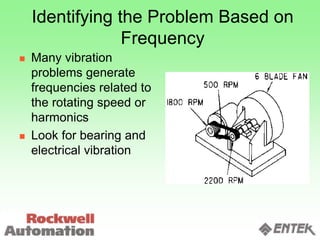

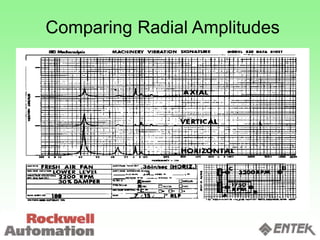

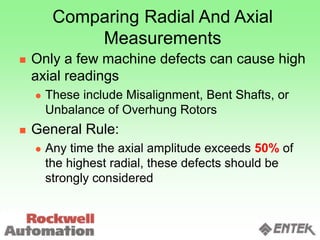

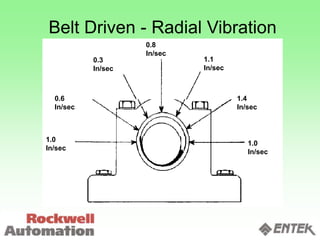

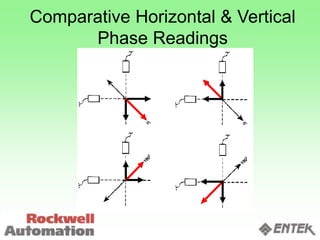

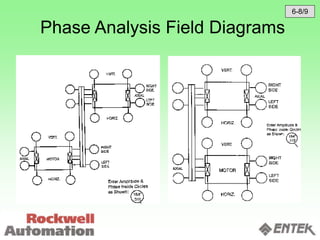

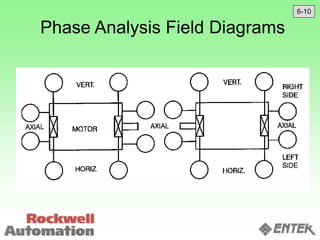

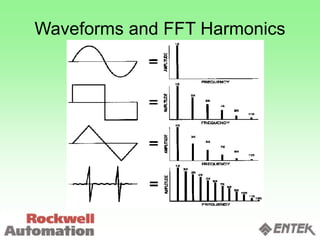

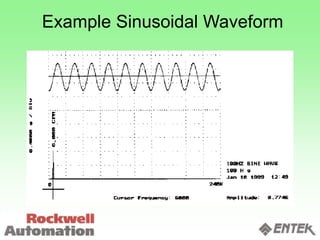

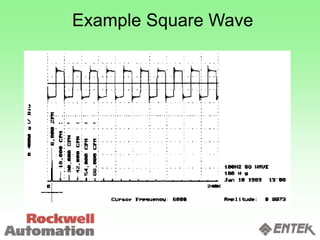

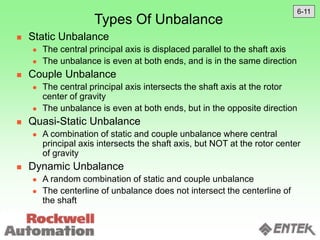

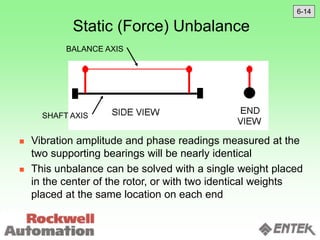

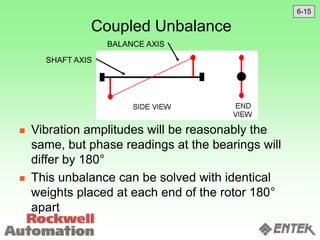

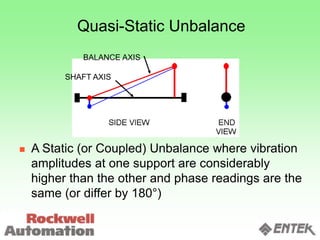

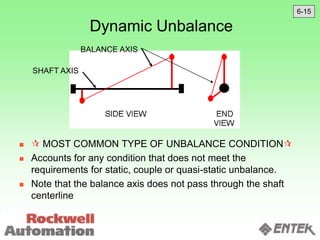

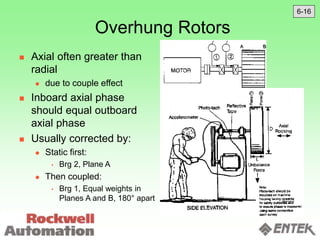

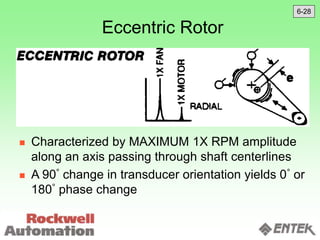

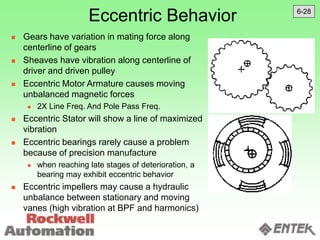

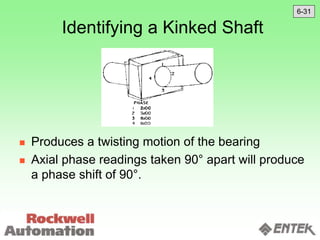

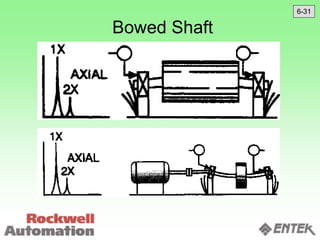

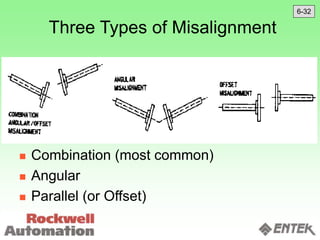

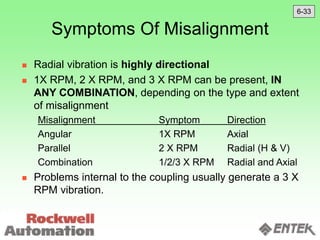

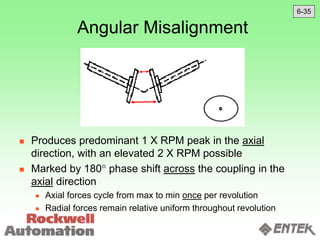

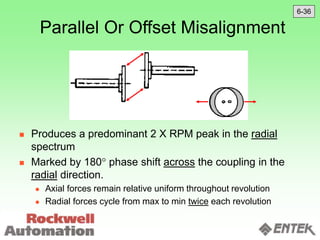

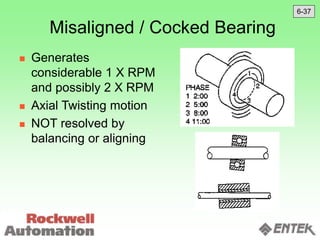

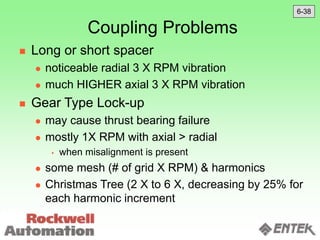

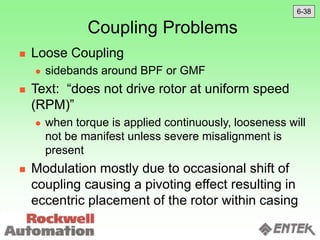

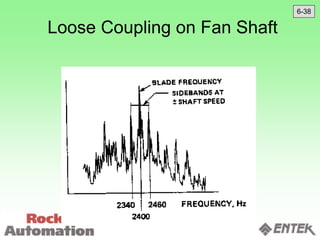

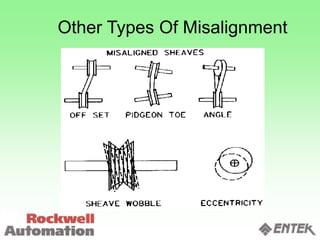

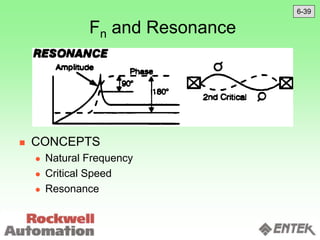

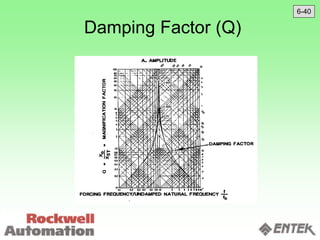

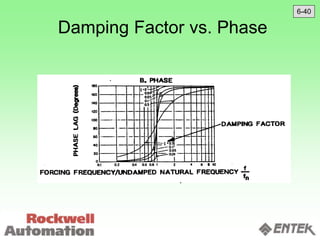

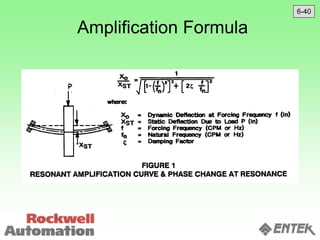

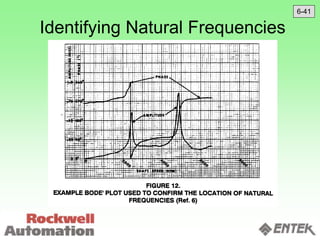

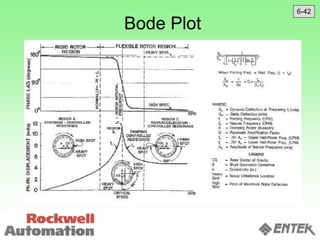

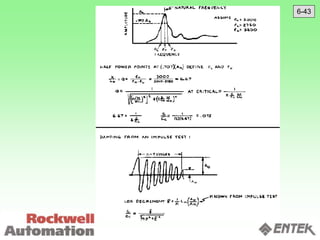

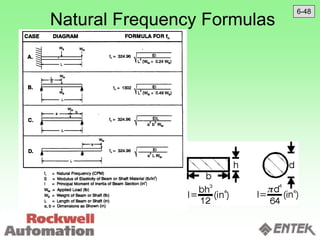

This document discusses vibration analysis and diagnostics. It outlines an 8 step analysis procedure including defining the problem, determining machine history and details, visual inspection, data collection, frequency confirmation, vibration direction/phase analysis, and probing studies. Specific vibration issues covered include unbalance, resonance, misalignment, bent shafts, and component failures. Diagnosing the root cause involves analyzing vibration frequency spectra and amplitudes across machine components.