This document summarizes and replicates previous research on the electoral effects of fiscal policies. It begins by summarizing 3 prior studies on the relationship between fiscal adjustments and electoral outcomes. It then describes the data and variables used, including measures of electoral outcomes. The document replicates the models from 2 prior studies. The replication finds support for the relationship between economic growth and reelection, but does not replicate the finding that deficits inhibit reelection. The document advocates using a continuous measure of vote share change rather than a binary reelection measure.

![3

from the International Monetary Fund (Guajardo, Leigh, and Pescatori 2011) casts doubt on the

validity of the “expansionary fiscal contraction” hypothesis.

One of the most-cited articles in the cross-national study of social policy asserts that

governments perceive welfare retrenchment as electorally costly, and thus avoid claiming

responsibility for cuts (Pierson 1996). This assumes that voters punish governments for cuts to

social programs, an assumption which subsequent research has challenged (Armingeon and

Giger 2008; Giger and Nelson 2010), using data on changes in benefit generosity as coded in

Scruggs (2004) rather than the level of expenditure. However, it is unclear whether the

retrenchment in question takes the form of fiscal adjustment (a reduction in social expenditure

without a corresponding increase in non-social expenditure or reduction in taxation), a revenue-

neutral reduction in social expenditure offset by a corresponding reduction in taxation, or a

revenue-neutral reduction in social expenditure offset by a corresponding increase in non-social

expenditure. These three forms of retrenchment have plausibly distinct electoral consequences,

each of which I will attempt to identify in the analysis.

Data and sample

In this section, I describe two ways in which researchers have measured electoral outcomes.

The most-cited study of the electoral effects of deficits uses a binary measure of incumbent

electoral success. An alternative approach, frequently used to identify the electoral effects of

macroeconomic conditions, calculates the change in vote share between elections for the

incumbent party. I advocate using the change in vote share, which is more accurate and precise

than the binary measure. To support this claim, I give specific instances in which the binary

variable erroneously measures electoral success or failure. Later, I will show more generally that

using the binary measure tends to produce biased estimates of the electoral consequences of

deficits.

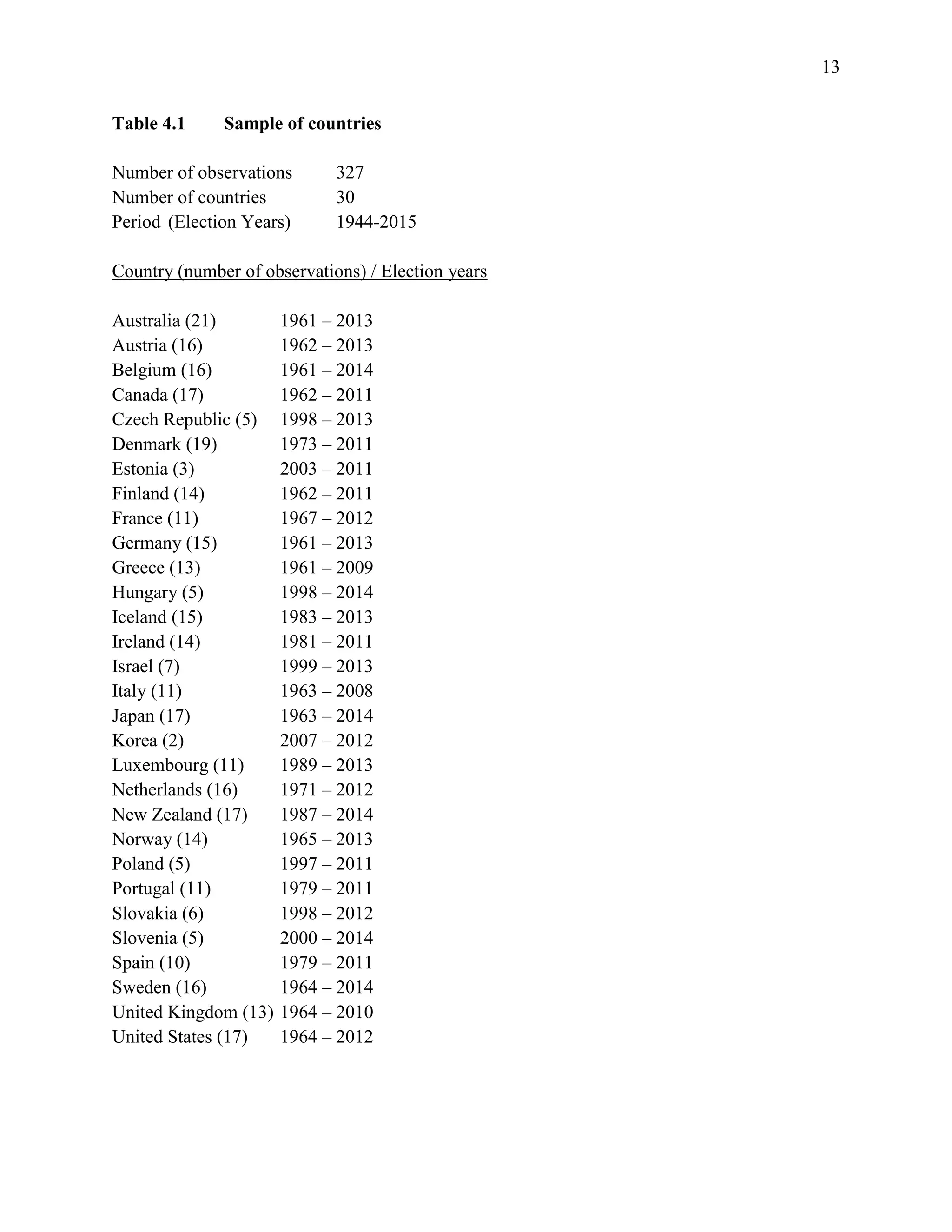

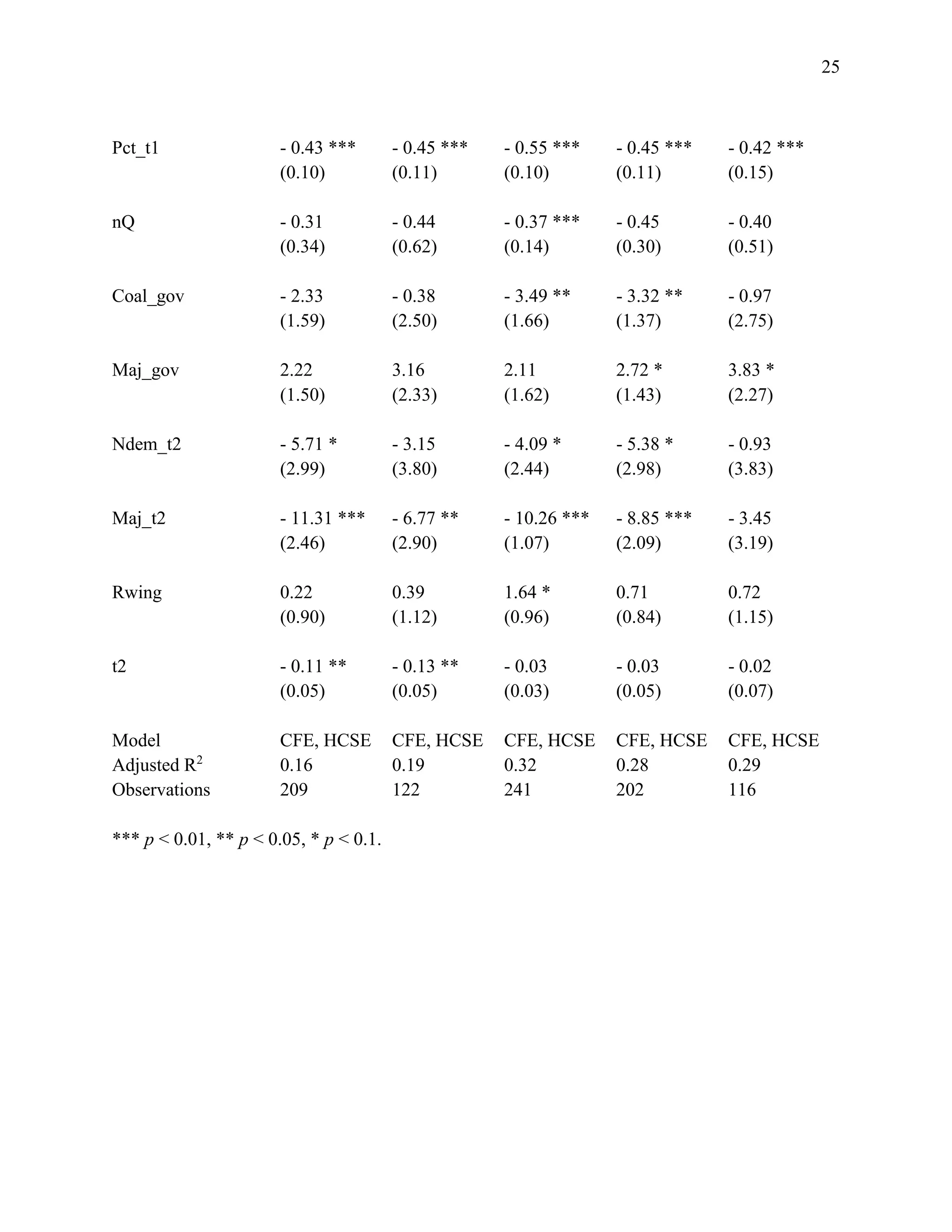

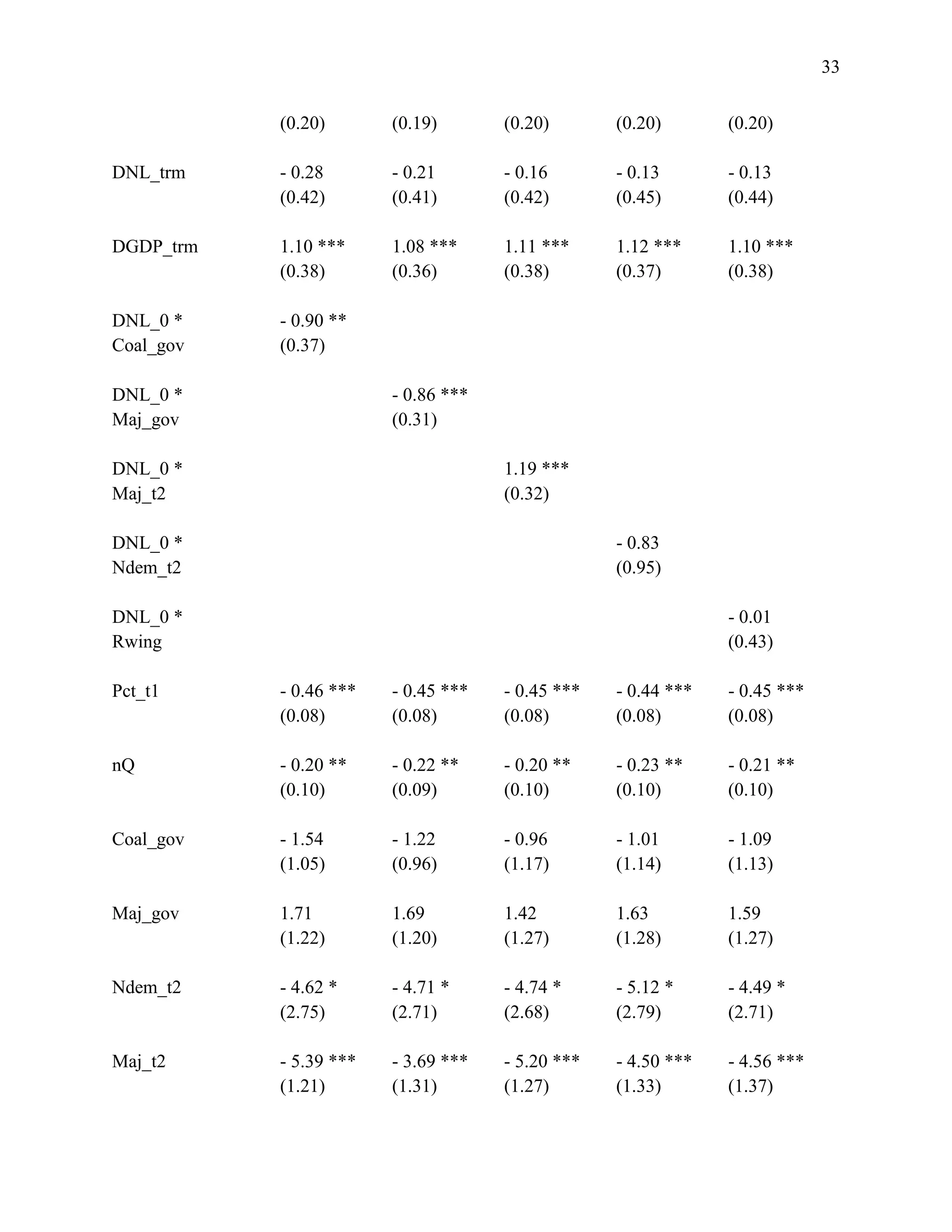

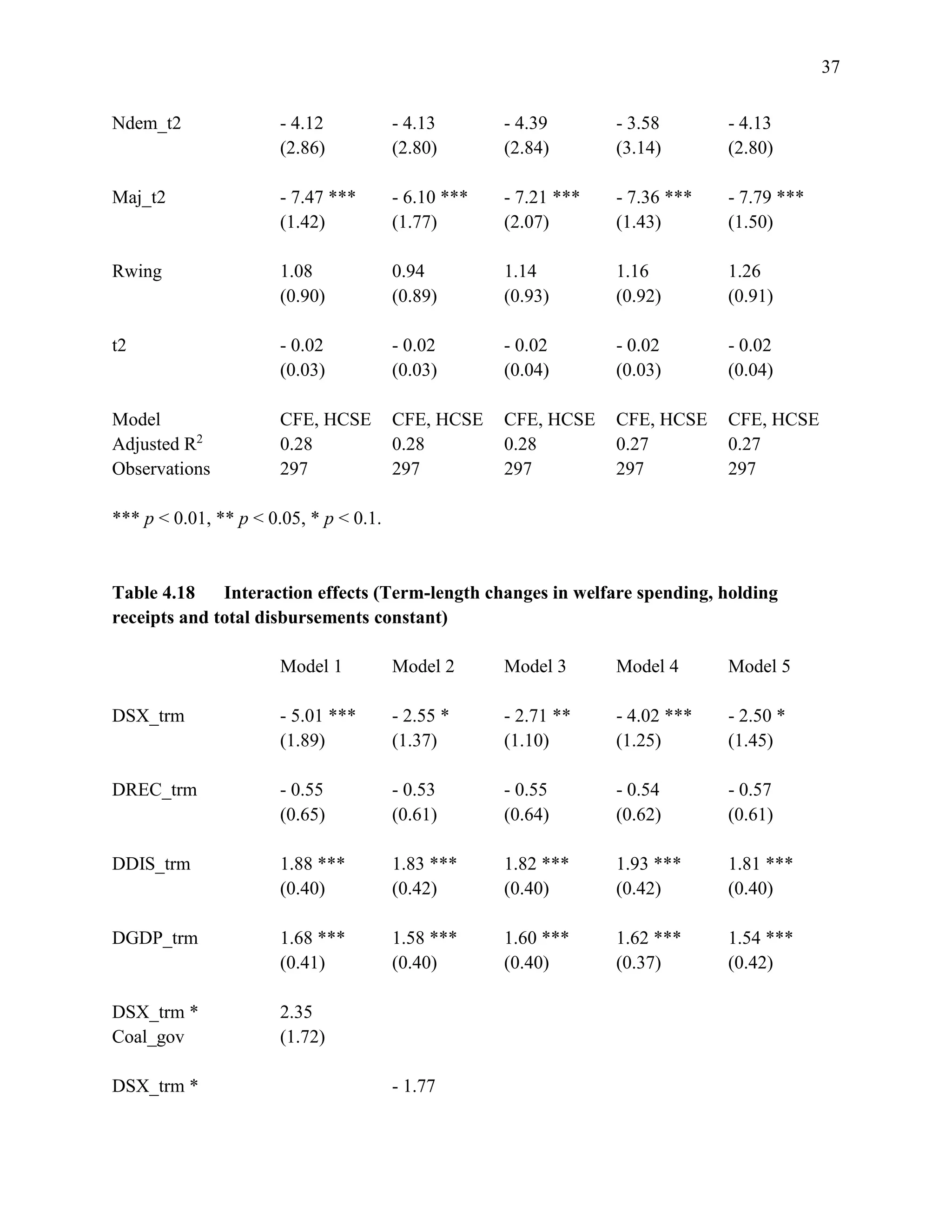

The sample consists of 355 democratic elections contested between 1948 and May 2015. For

a detailed description of the sample, and of other variables included in the analysis, see

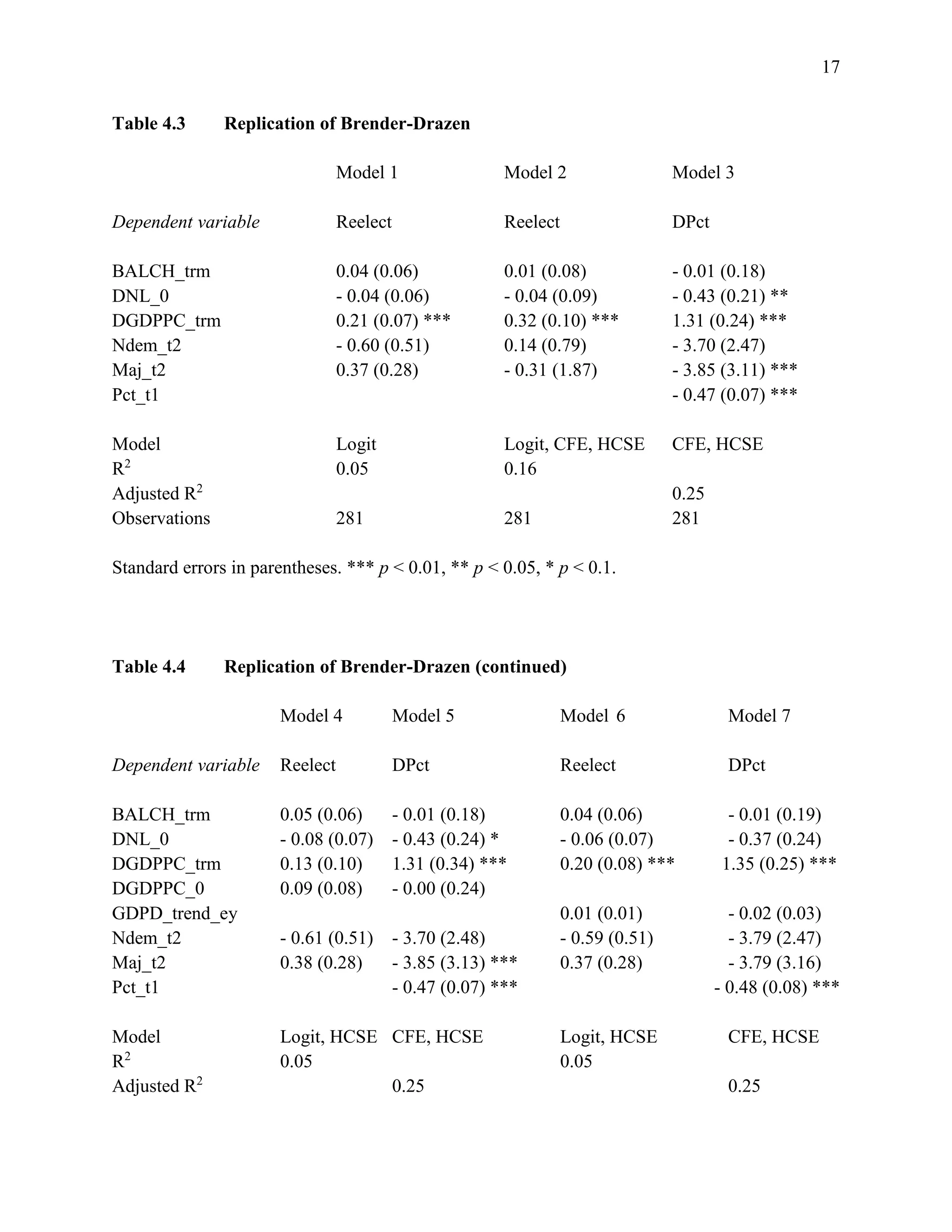

Appendix 4. Table 4.1 lists the election years and number of observations for all countries in the

sample. Table 4.2 presents descriptive statistics of each of the variables used in the statistical

models.

[Tables 4.1-4.2 here]

The response variable in each model is a measure of incumbent party electoral performance:

either a binary indicator of reelection (Reelect), equal to 1 if the party of the incumbent chief

executive is reelected and 0 otherwise; or a continuous measure of change in incumbent vote

share (DPct). Nyman (2014) suggests that incumbent governments may be more likely to

implement unpopular fiscal measures when they perceive that their loss in vote share will not

cost them reelection. This assumes that governments can adequately identify the prospective](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-3-2048.jpg)

![6

Replication

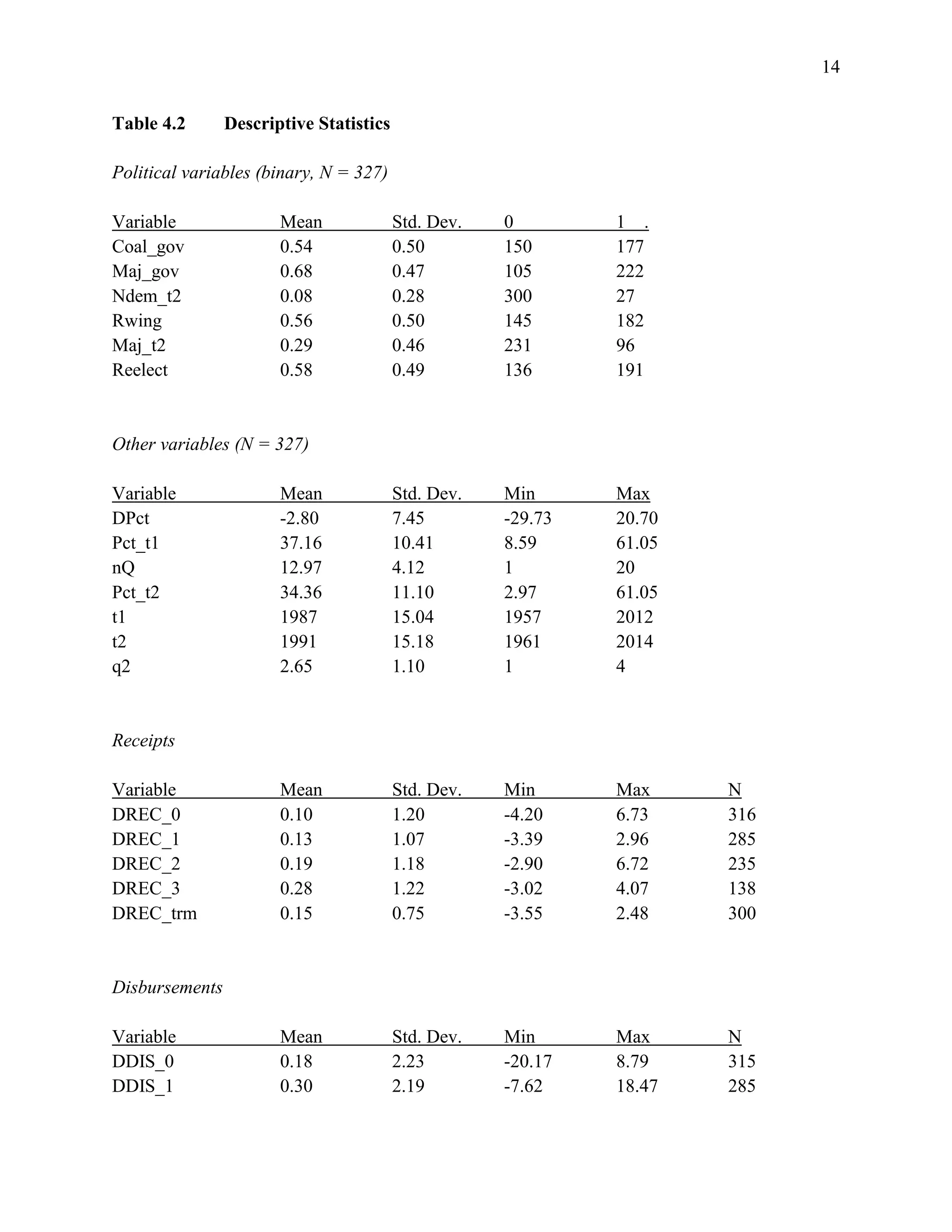

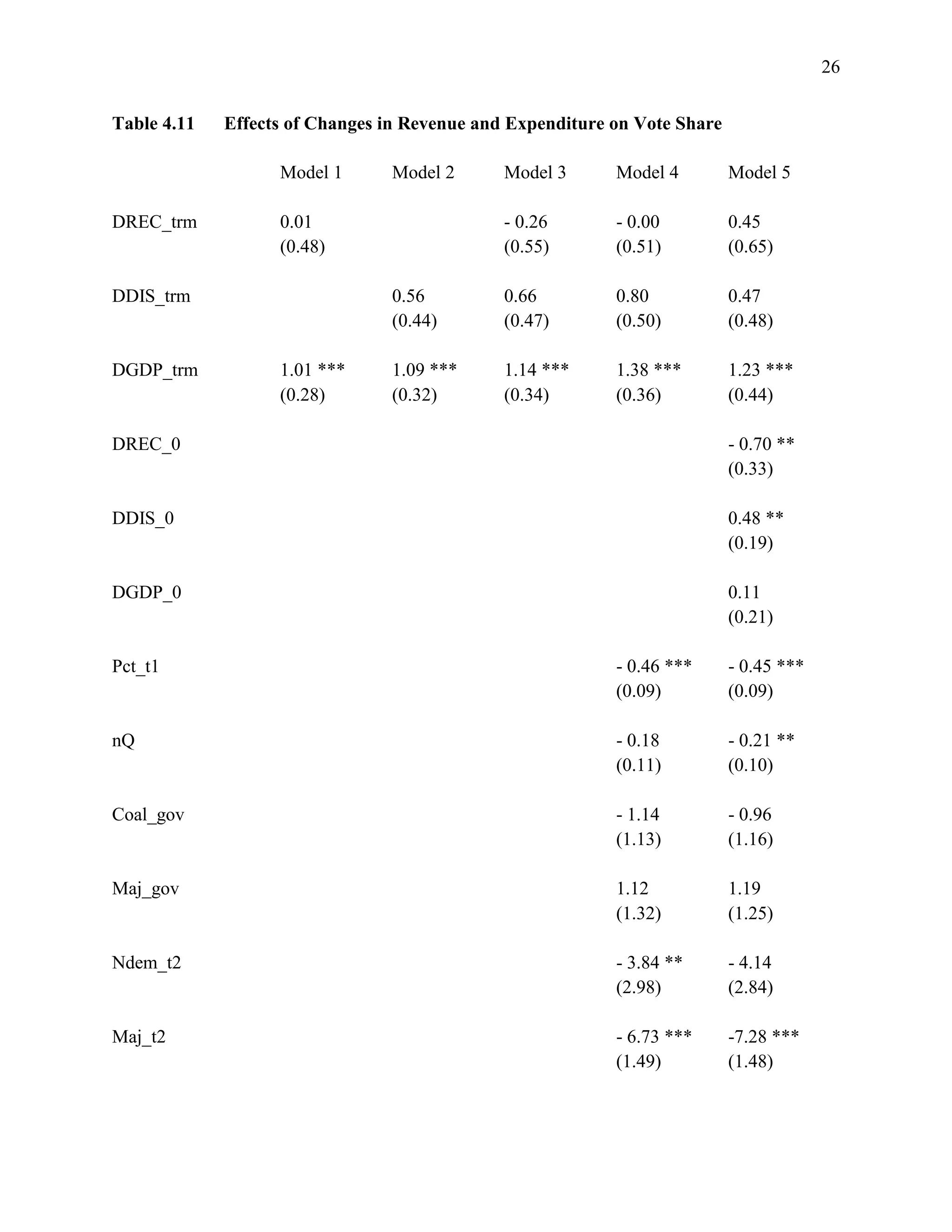

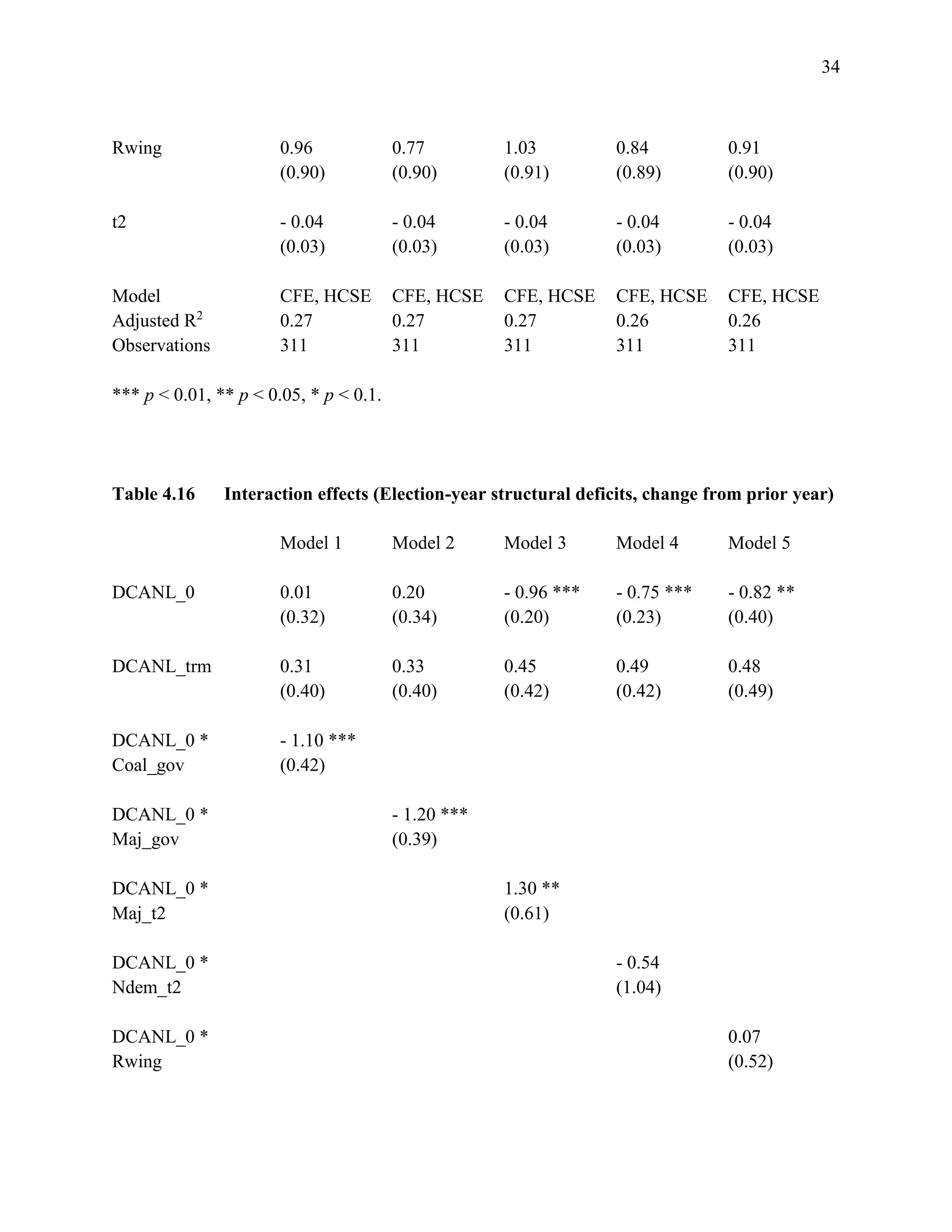

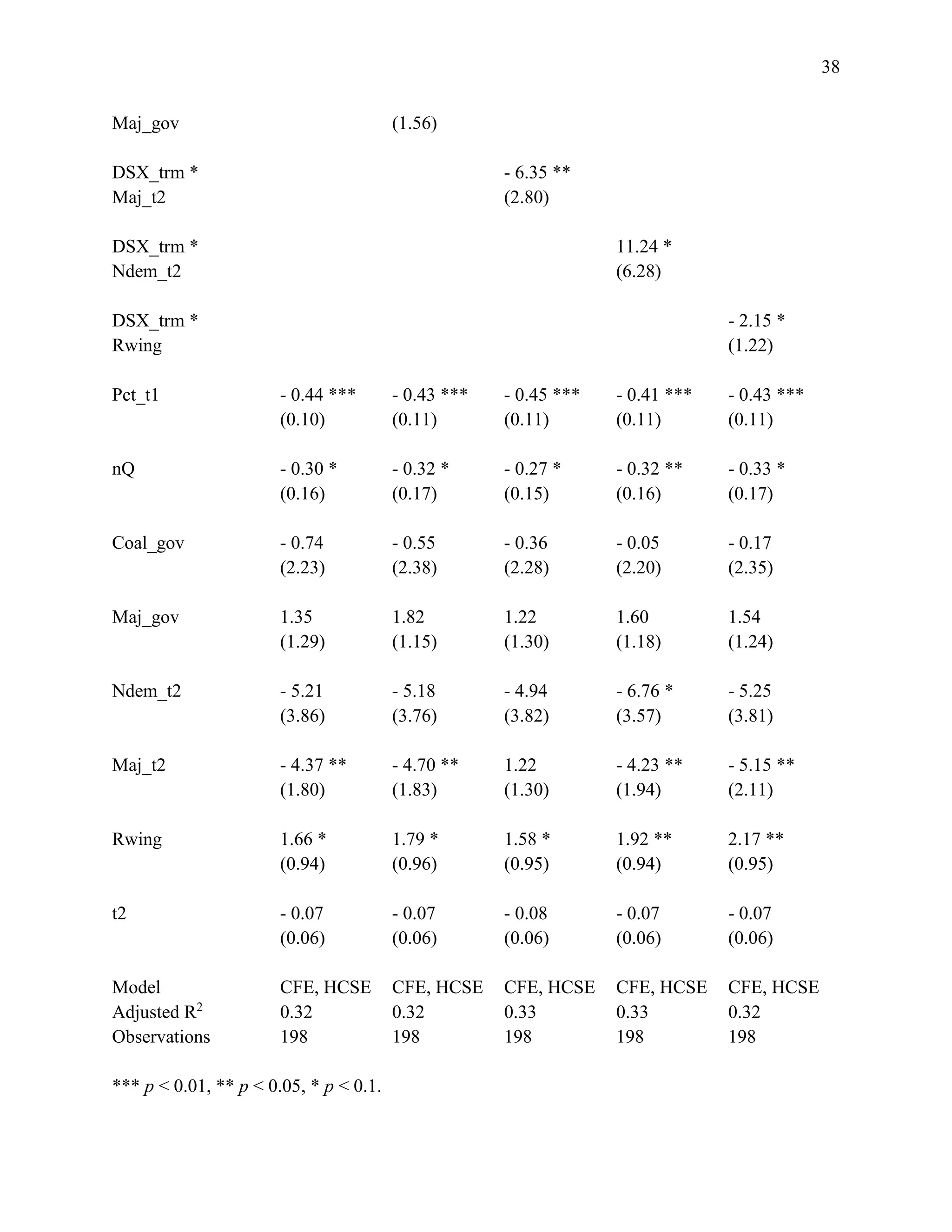

Following the approach taken in Chapters Two and Three, I first attempt to replicate the

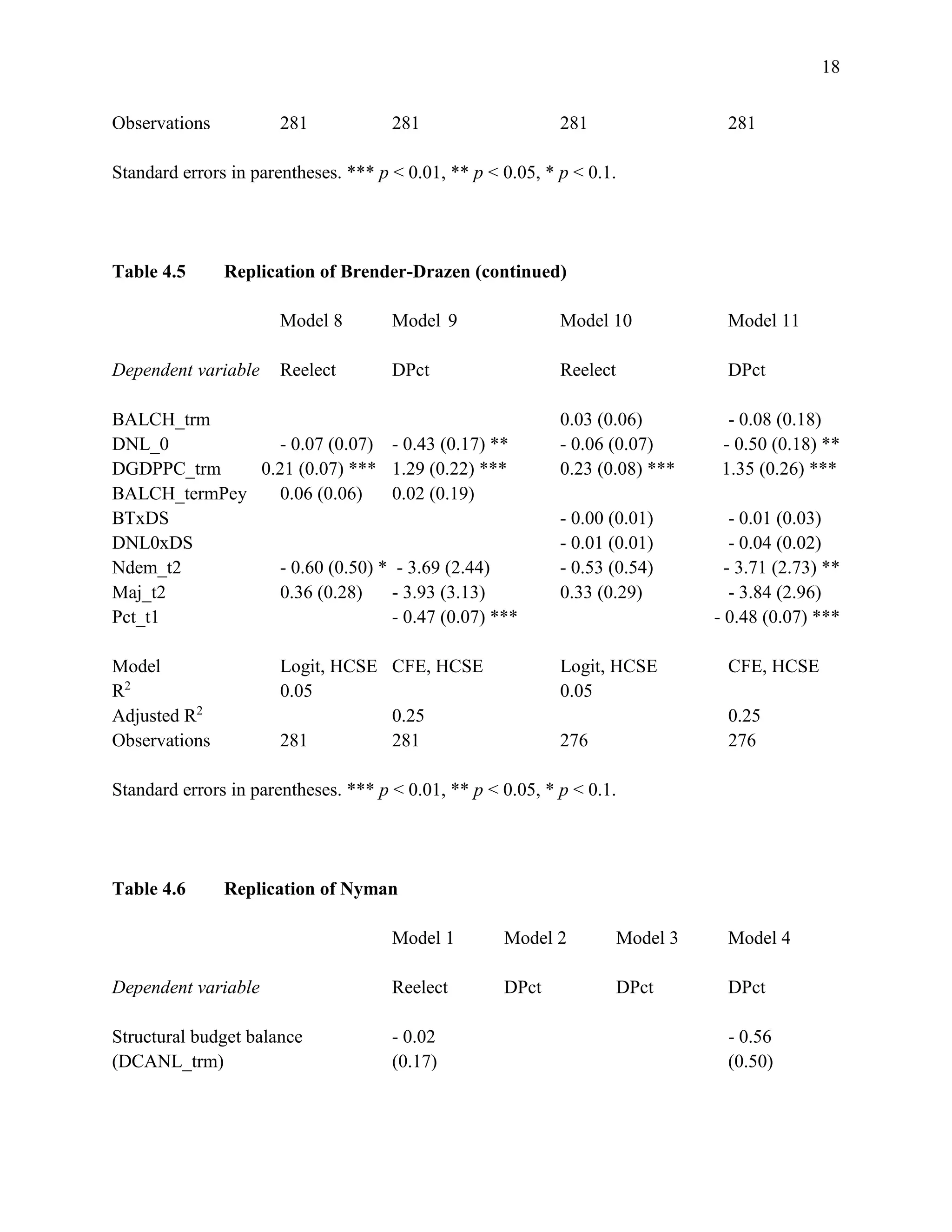

conclusions of Brender and Drazen’s analysis. In Models 1 and 2, the authors include variables

measuring the change in central government budget balance from the third and fourth year prior

to election to the two years prior to election (BALCH_trm), the election year change in budget

balance (DNL_0), and the change in GDP per capita over the chief executive’s term in office

(DGDPPC_trm). The authors include binary variables indicating whether or not elections were

held under majoritarian electoral rules (Maj_t2), or were one of the first four elections held since

democratic transition (Ndem_t2). Model 1 is estimated without country fixed effects. Model 2 is

estimated with fixed effects. The response variable in both models (Reelect) indicates whether or

not the party of the chief executive is reelected. As in Brender and Drazen (2008), both Models 1

and 2 are estimated by logistic regression (logit) with heteroscedasticity-consistent standard

errors.

Following Nyman (2014), I examine whether substituting a variable measuring the difference

in incumbent vote share between elections for the binary reelection indicator changes the

estimated effects of fiscal variables on reelection prospects. Since incumbents with a higher

initial vote share are more likely to lose votes between elections, I include a variable (Pct_t1)

measuring incumbent vote share from the previous election. I estimate Model 3 using ordinary

least squares regression with country-level fixed effects and heteroscedasticity-consistent

standard errors. Table 4.3 presents my initial replication of Brender and Drazen’s models.2

[Table 4.3 here]

Table 4.3 provides additional support for Brender and Drazen’s claim that the probability of

incumbent reelection increases with the change in GDP per capita. However, the authors’

conclusion that deficits inhibit reelection does not replicate for the sample of countries examined

here. Using both the binary and continuous measure of electoral performance, I find instead that

inter-election changes in the budget balance have no significant effect on reelection prospects.

More notably, the change in incumbent vote share decreases with the budget balance, directly

contradicting the authors’ finding that voters in developed countries “do not like deficits,

particularly in election years” (Brender and Drazen 2008, p. 2215).

One possibility is that the authors’ findings are sensitive to the selection of countries and

time period. Brender and Drazen define countries (more restrictively) as “developed” if they

were members of the OECD prior to 1974. Hence they include Mexico and Turkey in their

sample of developed countries, but exclude South Korea and the former Eastern Bloc countries.

Their sample covers many of the same elections from 1961 to 2003, but includes observations

for which OECD data is not available, and excludes observations after 2003.

2

I report R2

as 1 – RSS/MSS for the logit models, and the adjusted R2

for the fixed effects regressions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-6-2048.jpg)

![7

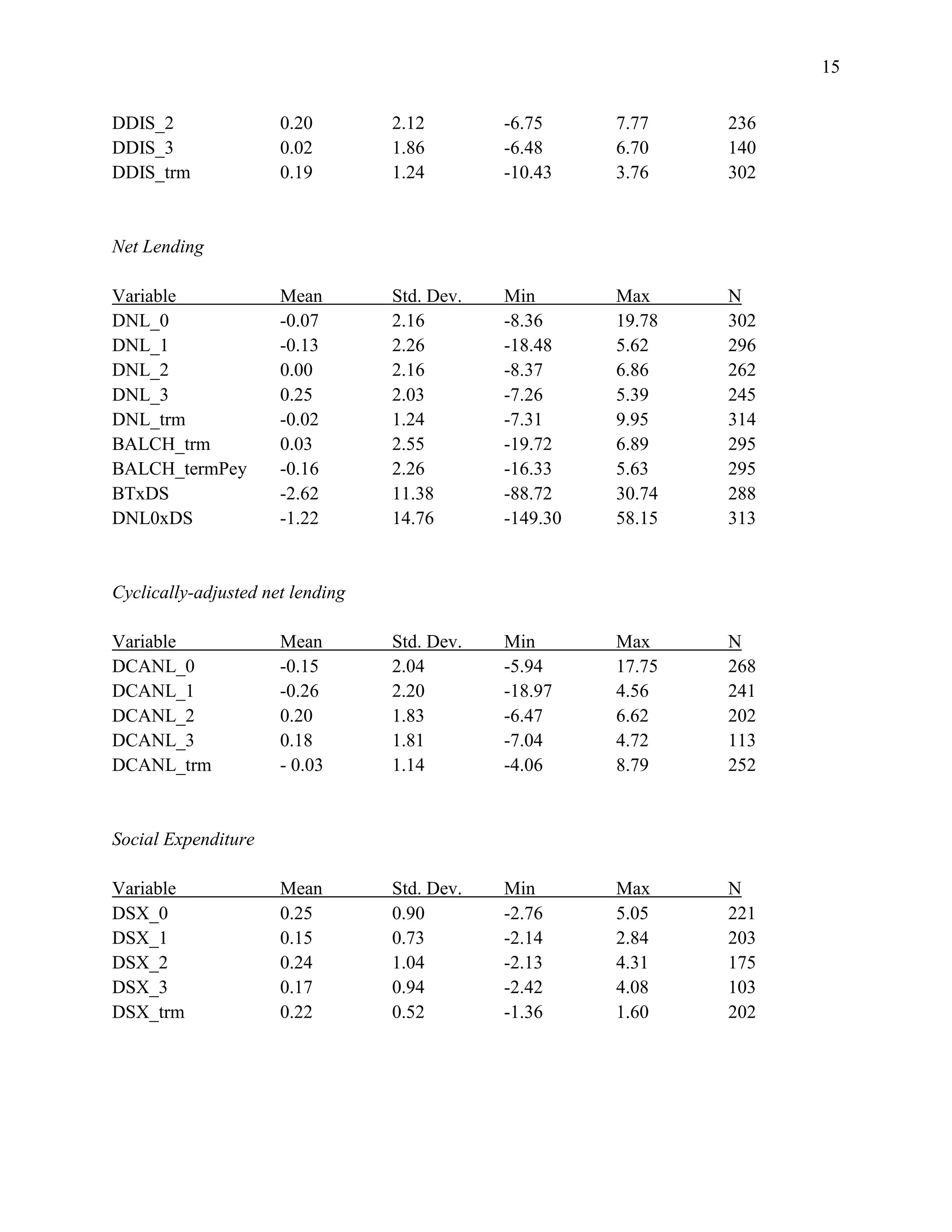

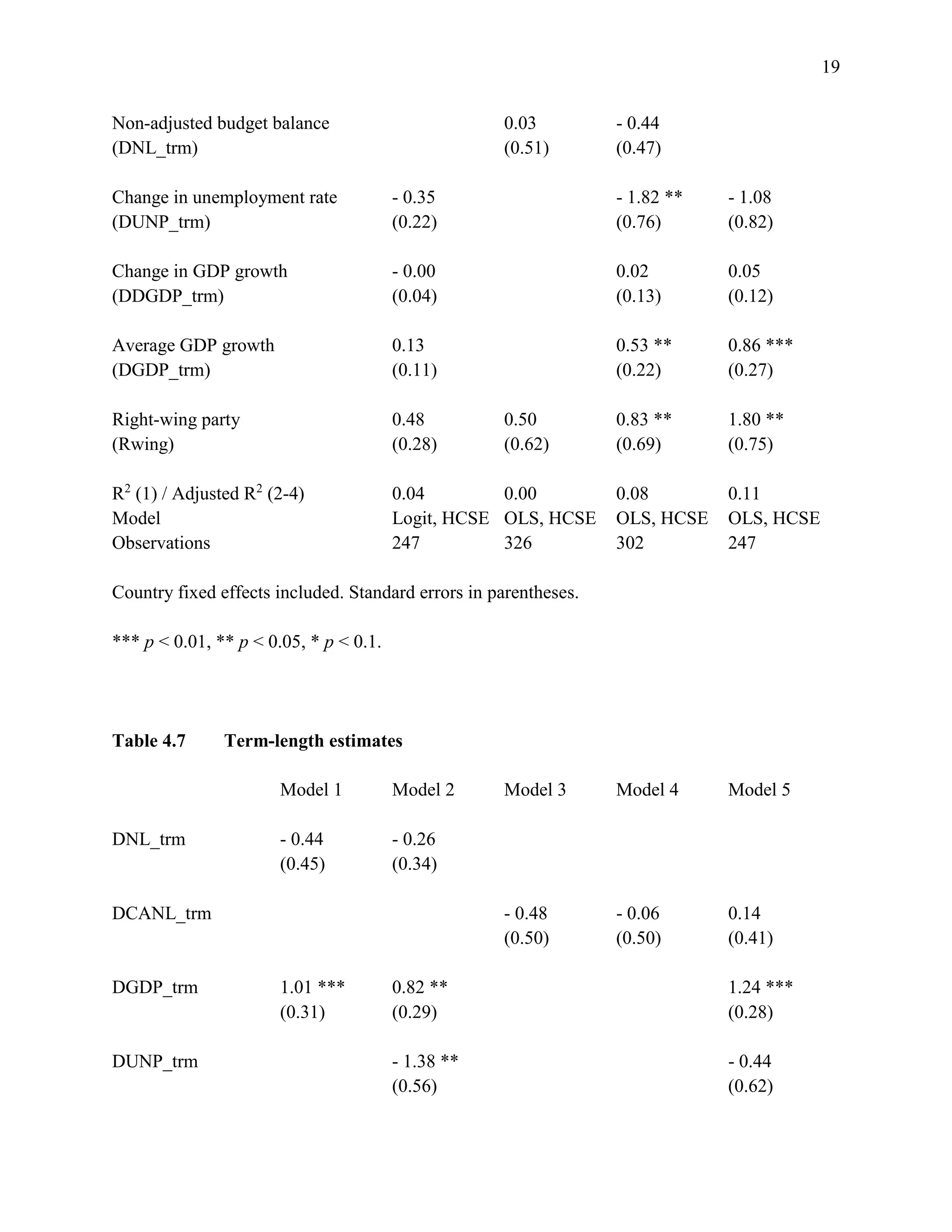

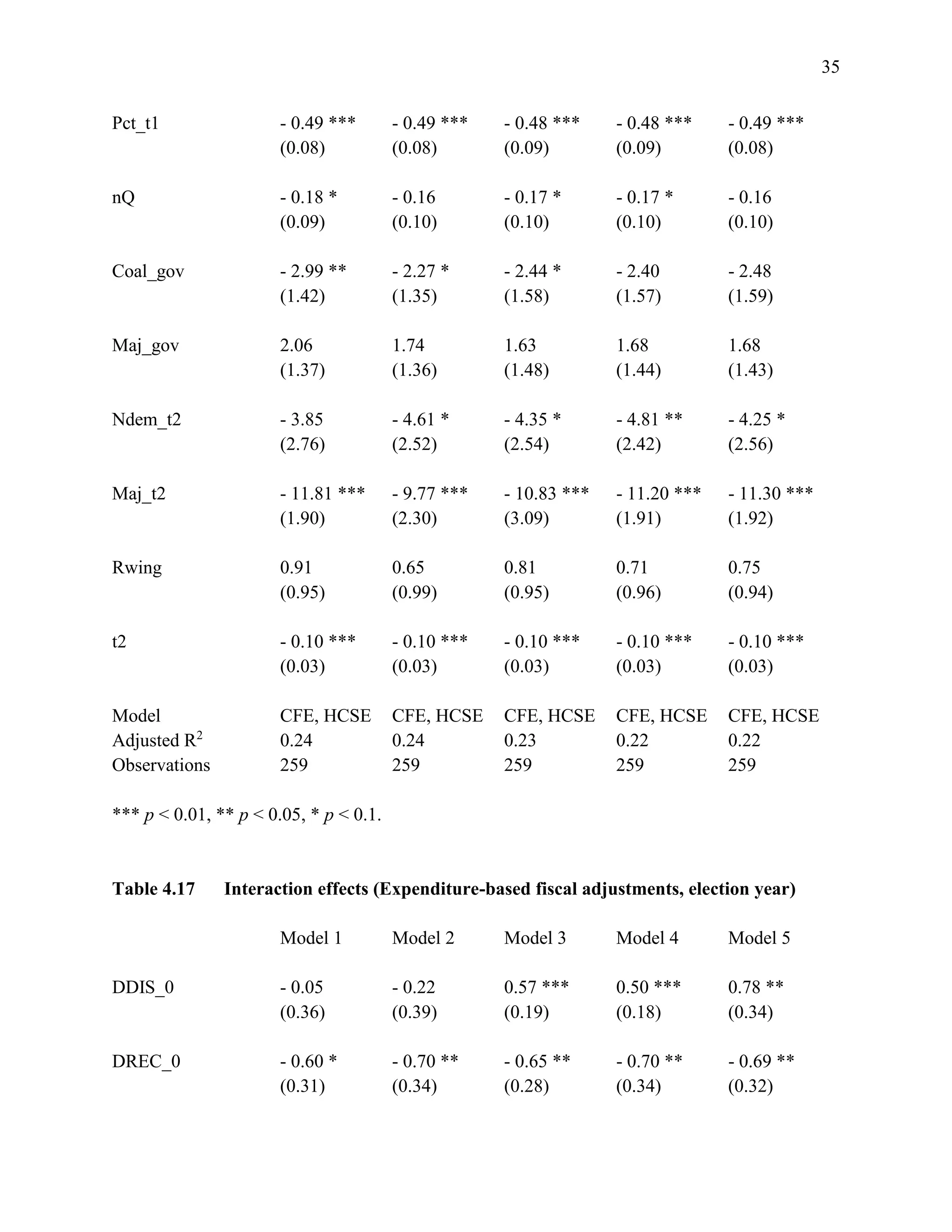

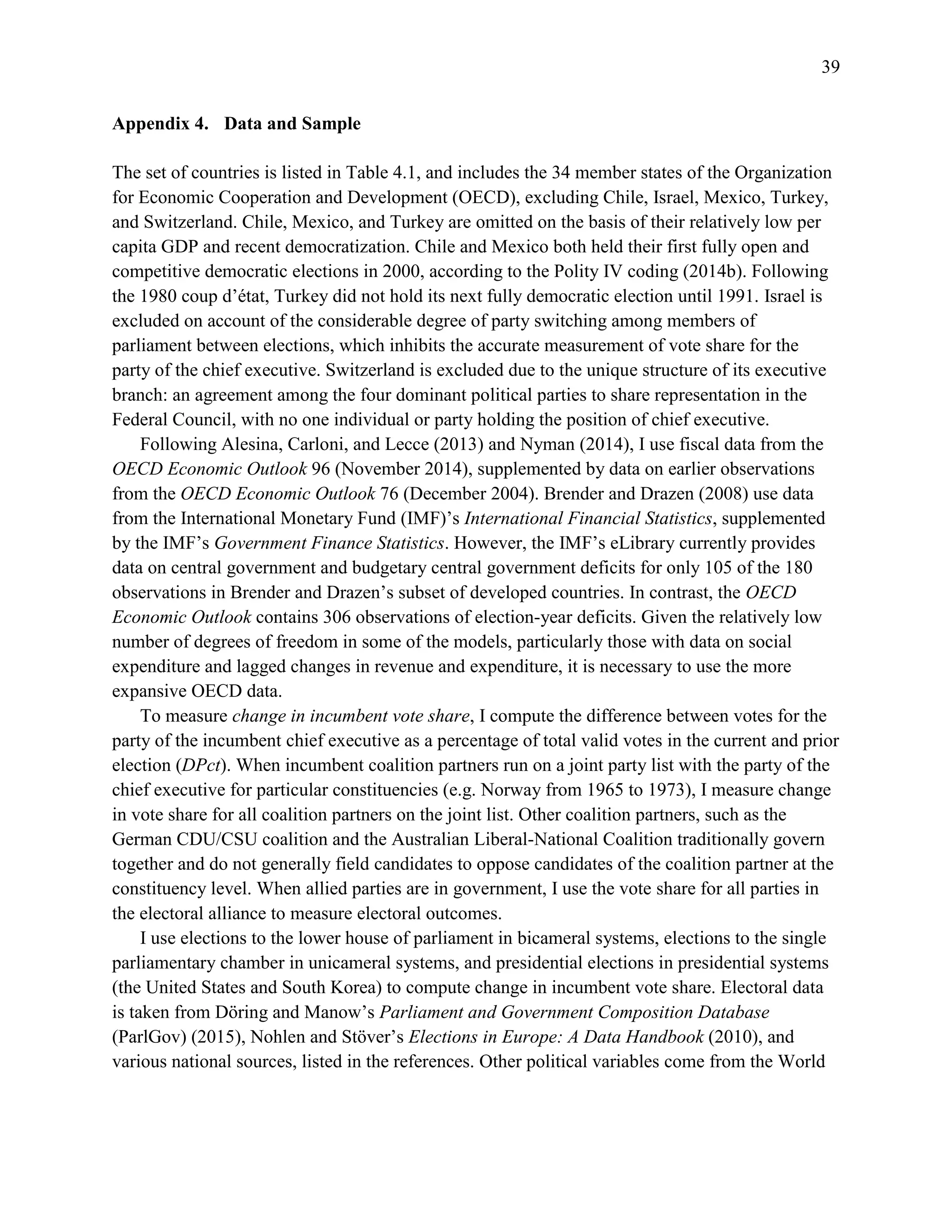

In Models 4 through 7, I replicate Brender and Drazen’s estimates of the electoral

consequences of changes in the government budget balance, controlling for election-year

changes in economic output. Again, I find that voters generally favor looser fiscal policies in the

year of election. Changes in the budget balance over the course of the election term have no

significant effect on reelection. Models 8 through 11 add alternative statistical controls but yield

the same conclusions.

[Tables 4.4 – 4.5 here]

Nyman’s basic model estimates the effect of term-length changes in the structural budget

balance on the change in incumbent vote share. Controlling for the partisan composition of

government and changes in GDP and unemployment, Nyman finds that an increase in the

general government budget balance over the course of the election cycle – with and without

cyclical adjustment – significantly corresponds to a decline in incumbent vote share (but does not

significantly affect the probability of reelection). Table 4.6 presents the estimates from my

reanalysis of Nyman’s models.

[Table 4.6 here]

Replicating Nyman’s models, I find no statistically significant relationship between the change

in the (cyclically-adjusted) budget balance and the change in the incumbent government’s vote

share. The coefficients are weaker, perhaps due to the inclusion of additional observations and

revision of prior observations from the more recent edition of the OECD Economic Outlook.

Nyman clusters standard errors at the country level, and I report heteroscedasticity-consistent

standard errors, but this cannot explain the variation in the coefficients between the authors’

estimates and the ones reported here.

Following replication of two prior studies, it is not evident that term-length changes in the

budget balance affect reelection prospects. In the following section, I provide new tests of the

hypothesis that fiscal expansions or contractions over the course of an incumbent’s term in office

significantly affects the change in incumbent party vote share. I again find no evidence that

changes in the budget balance from the prior election or change in party of the chief executive to

the current election corresponds significantly to an increase or decline in incumbent vote share.

However, I find consistent evidence that voters punish contractionary fiscal policies in election

years.

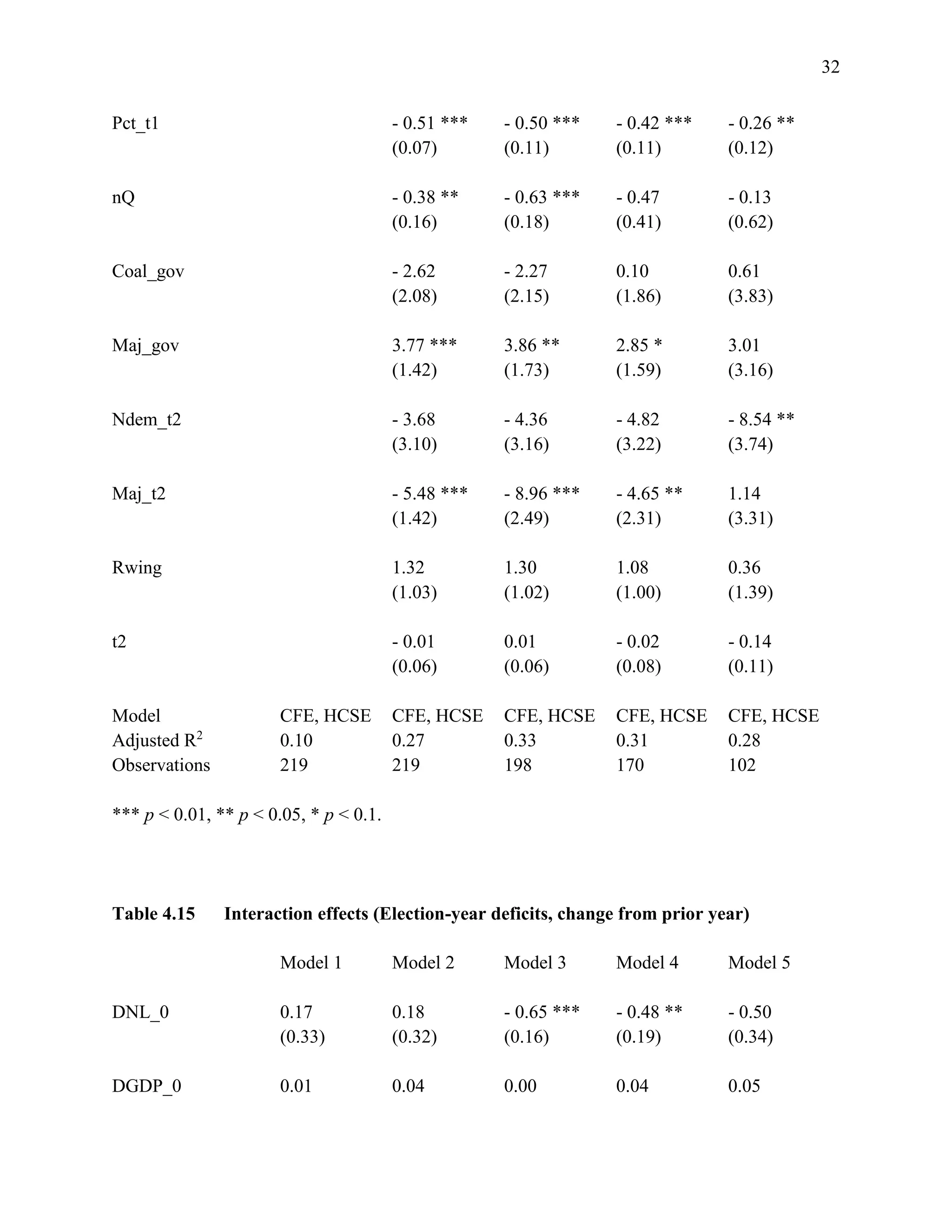

Term-length vs. election-year estimates

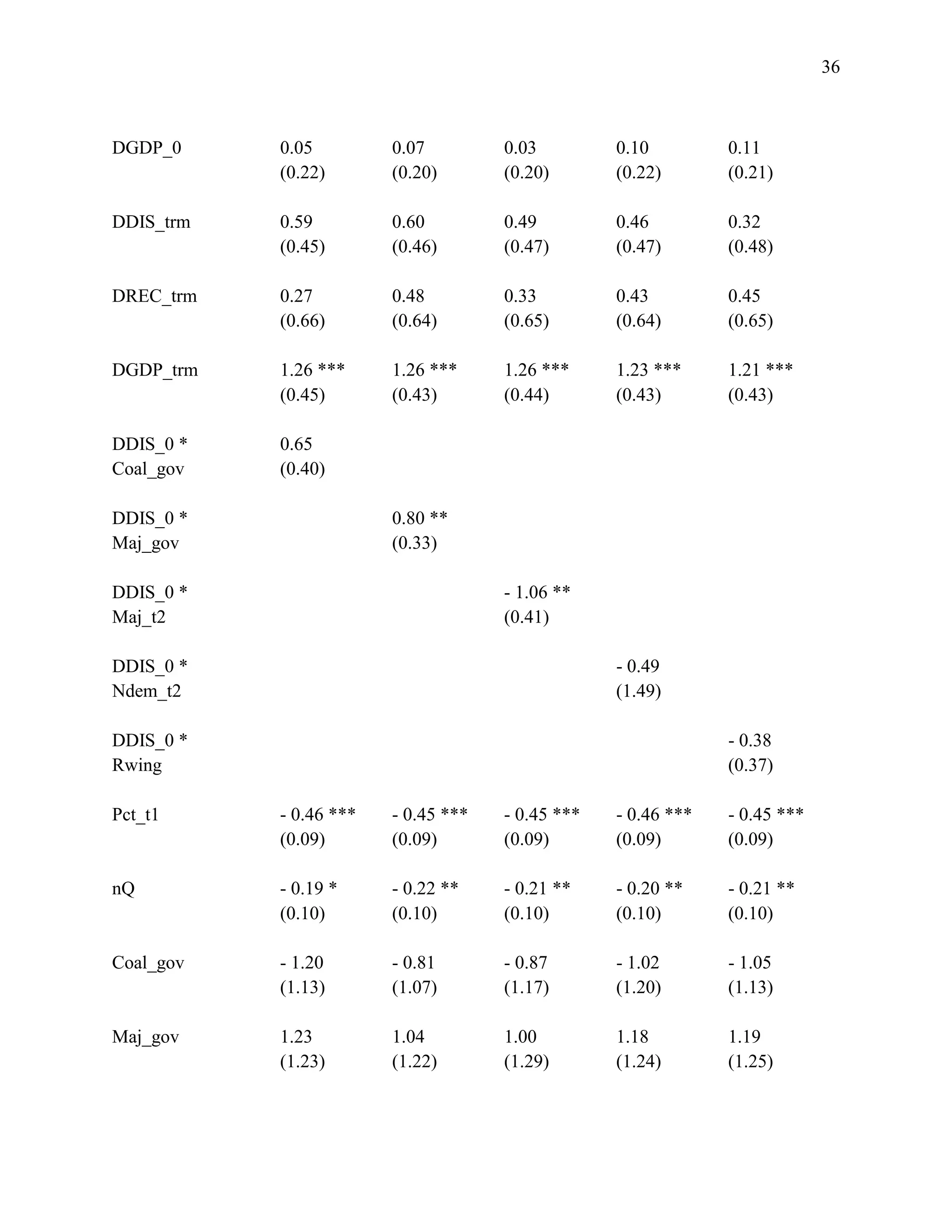

As the replication of Brender and Drazen’s models shows (using change in incumbent vote share

rather than a binary measure of reelection), the electoral consequences of changes in the

government budget balance depend critically on whether fiscal expansions or contractions occur

in the year of election or earlier in the term. This finding is consistent with a host of prior studies](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-7-2048.jpg)

![8

on the macroeconomic determinants of electoral outcomes, which tend to show that voters are

highly myopic: they reward or punish incumbents for economic conditions in the year of election

while discounting prior changes in national, regional, or personal income. Interestingly, election-

term changes in GDP correspond significantly to changes in incumbent vote share in replication

of Brender and Drazen’s model, but election-year growth has no statistically significant effect

when controlling for term-length effects.

Political economists have used evidence of voter myopia (or assumed its existence) to

explain the presence of political business cycles and budget cycles. If voters discount economic

conditions at times that are relatively distant from the following election, then governments have

an incentive to implement expansionary fiscal (and monetary) policies prior to elections and

contractionary policies immediately after elections. Governments should thus cut taxes and

expand spending prior to elections, increasing voters’ take-home income (in the short run) and

(more controversially) expanding national income through increasing aggregate demand. In

return, voters reward governments for expansionary policies. In the following models, I provide

additional evidence that voters reward election-year fiscal expansions. The effects are consistent

across alternative model specifications, using both uncorrected and cyclically-adjusted measures

of general government net lending.

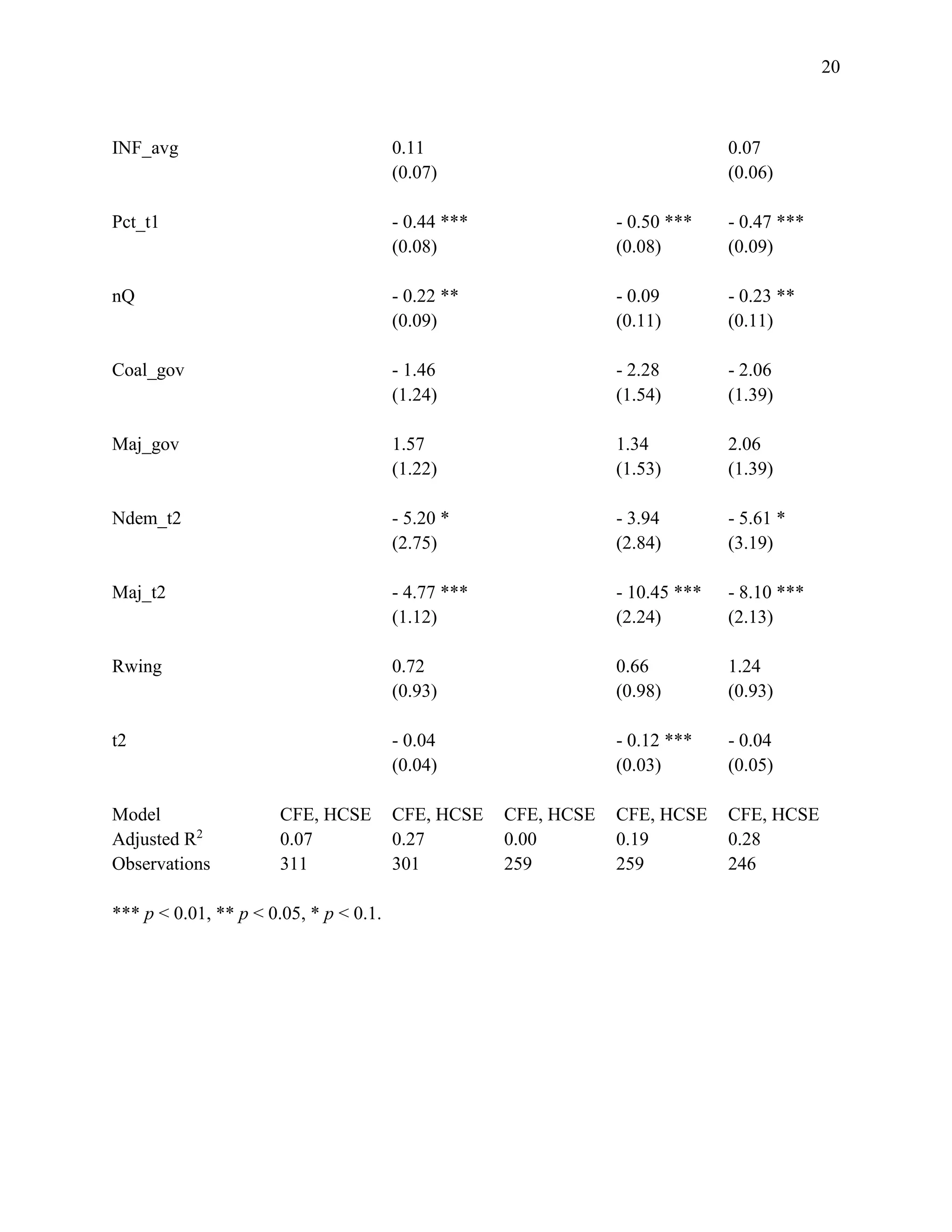

[Table 4.7 here]

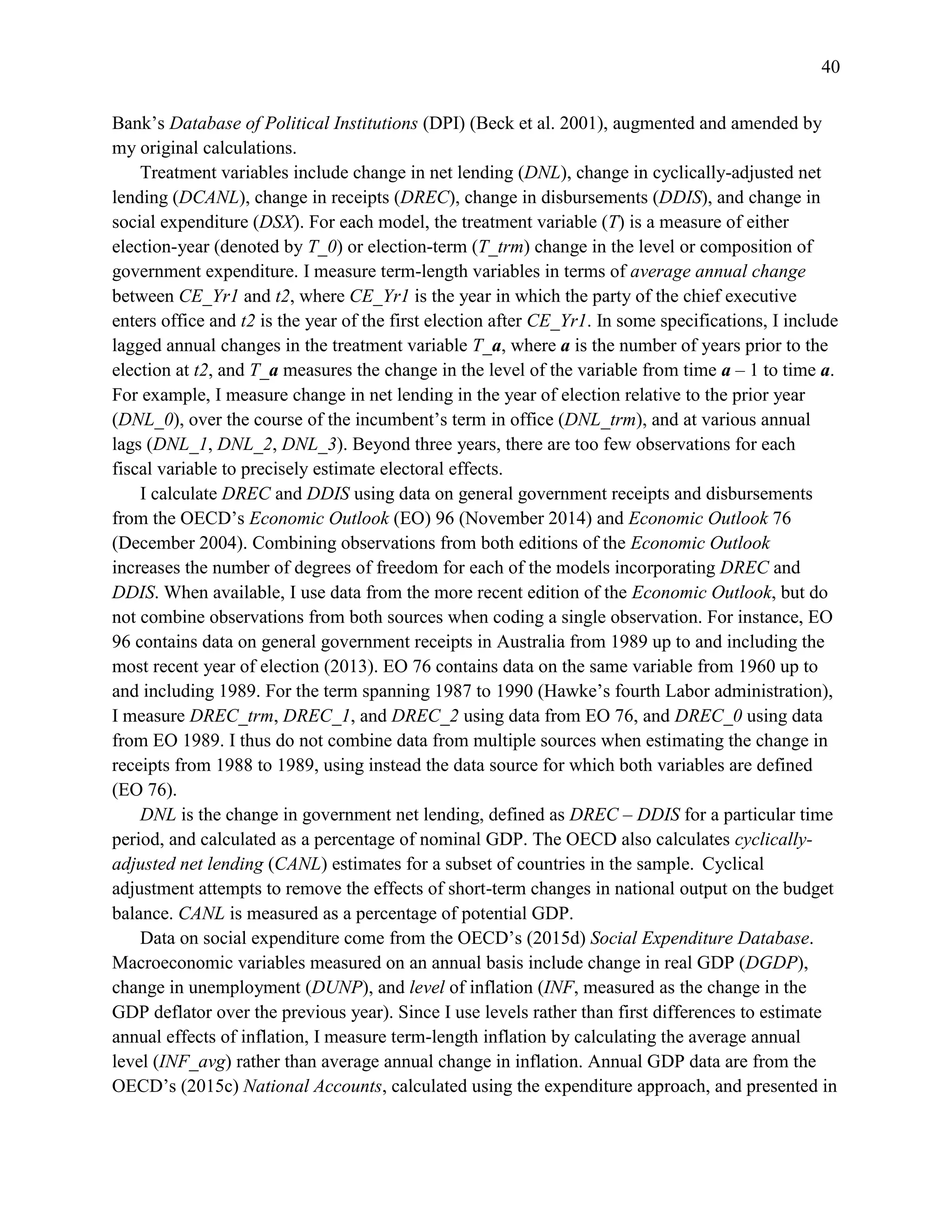

Table 4.7 shows that election-term changes in the budget deficit do not significantly affect the

vote share of incumbent governments. Although the coefficients on the net lending variables are

all negative, the standard errors are too large to conclude that term-length changes in the deficit

reduces incumbent vote share. In Model 1, I estimate term-length effects using general

government net lending (receipts less disbursements), controlling for changes in GDP. Model 2

adds additional economic and political controls. Model 3 presents the bivariate regression of

incumbent vote share on the change in cyclically-adjusted net lending. In Model 4, I add control

variables measuring the effect of potentially confounding differences in political institutions and

government characteristics. Model 5 includes economic controls. Although cyclical adjustment

attempts to account for the effect of changes in output on net lending, the inclusion of economic

control variables has no effect on the substantive findings of any of the models in the analysis.

In these models, and in subsequent specifications, I include control variables measuring

incumbent vote share in the prior election (Pct_t1). Incumbent governments elected with a larger

vote share tend to lose more votes in subsequent elections. To account for unobserved potentially

confounding cross-country variation, I estimate all models using country fixed effects. I include

a variable measuring the time of election, but exclude year fixed effects, which would

substantially reduce the number of degrees of freedom in each model. Fortunately, Hausman

tests reject the null hypothesis of consistency between models that include and exclude country

fixed effects (p < 0.001), but not between models that include and exclude year fixed effects.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-8-2048.jpg)

![9

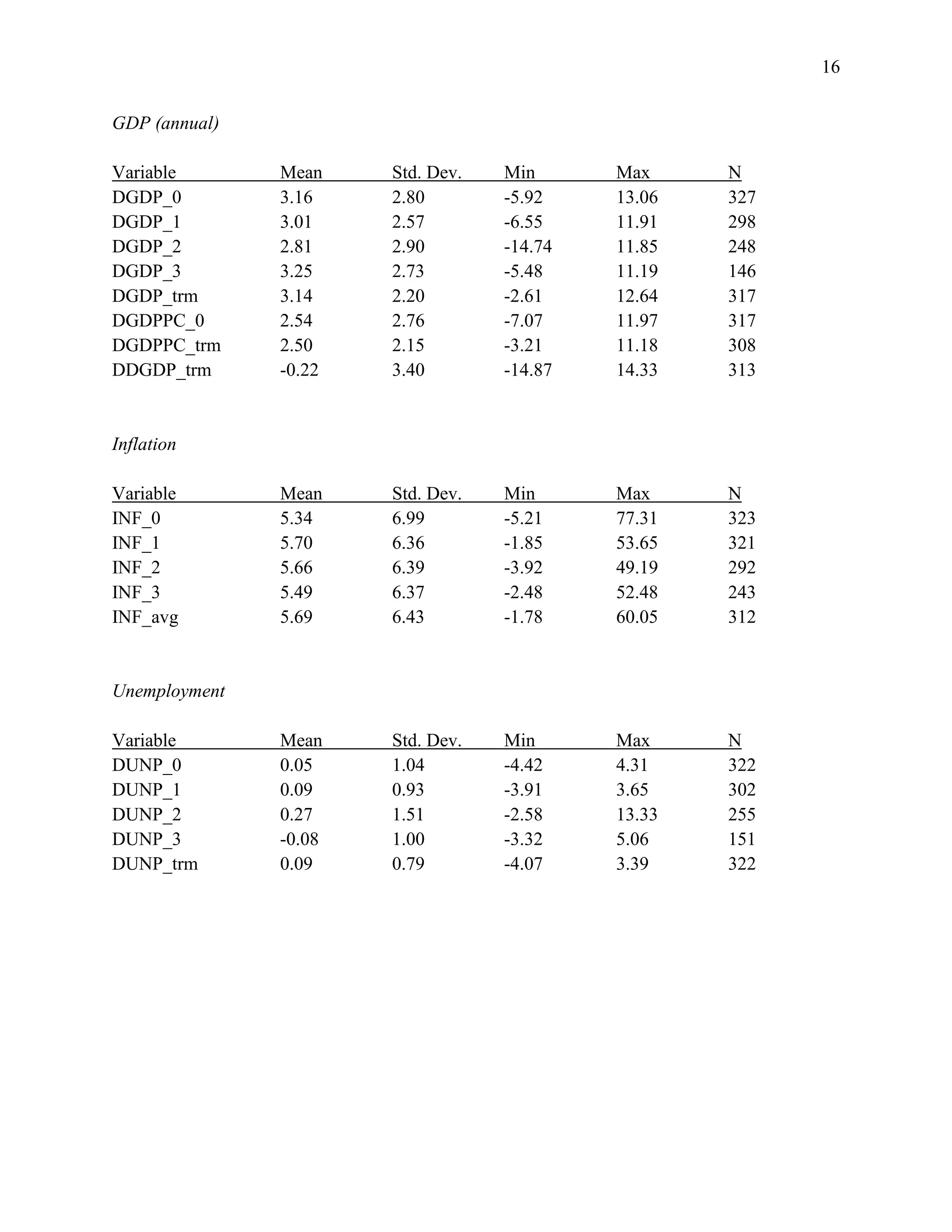

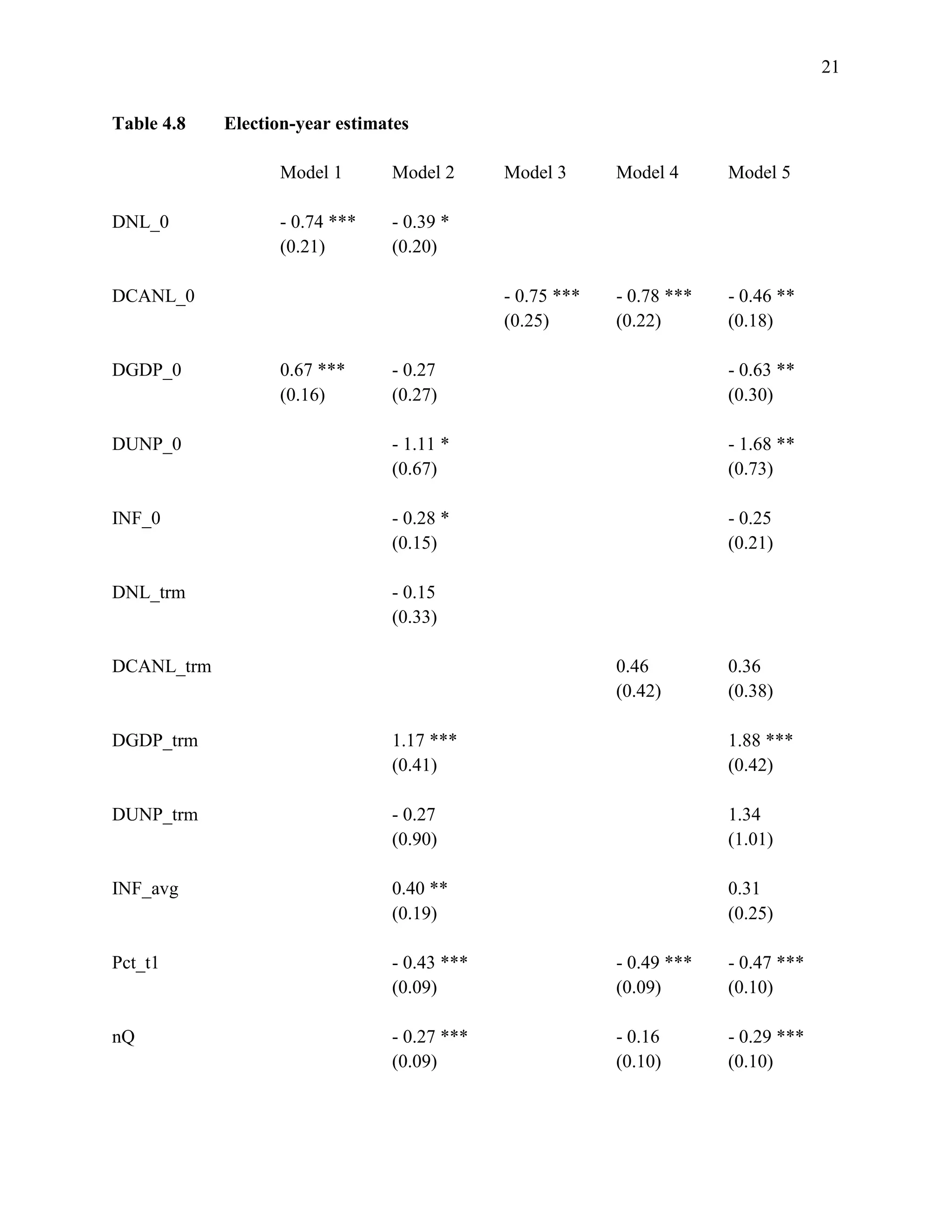

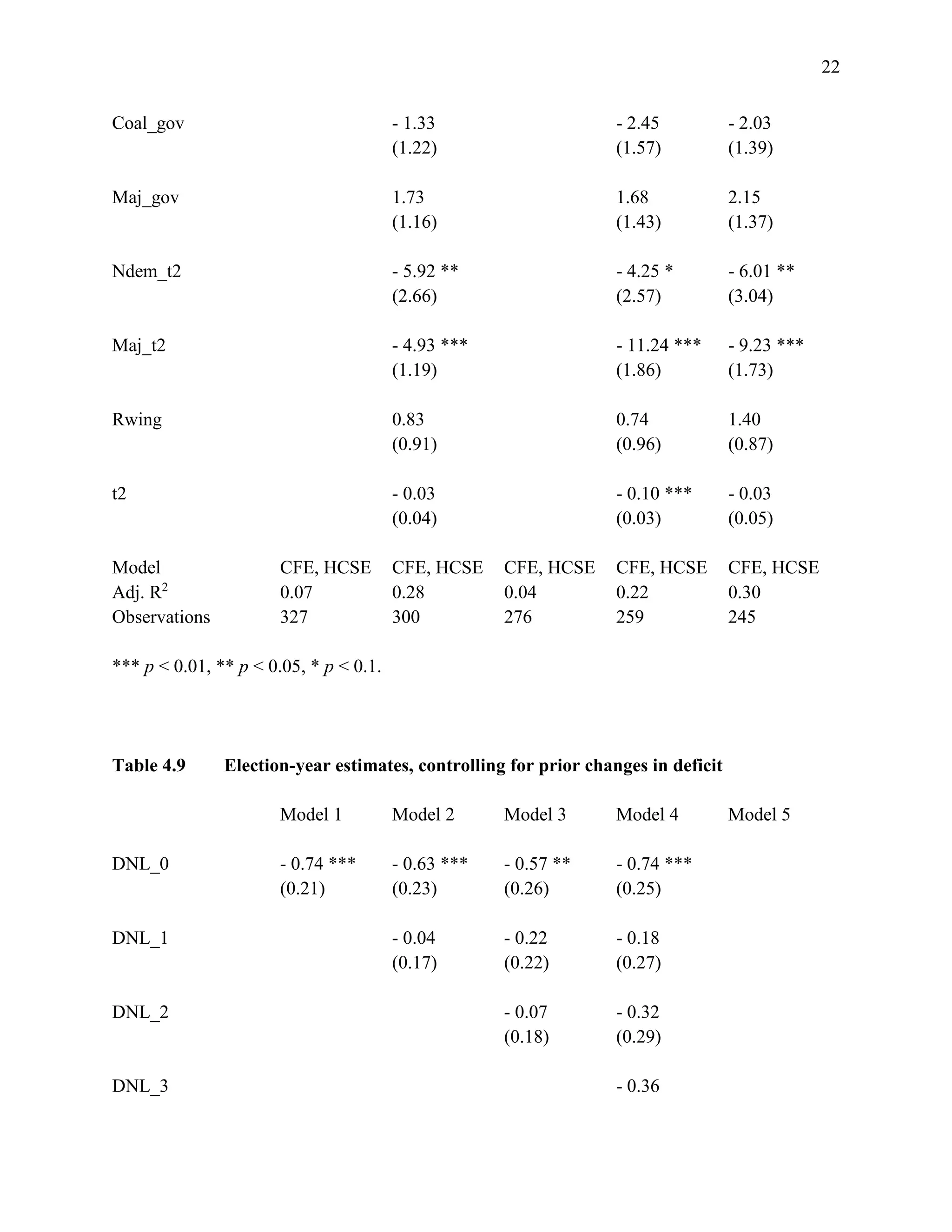

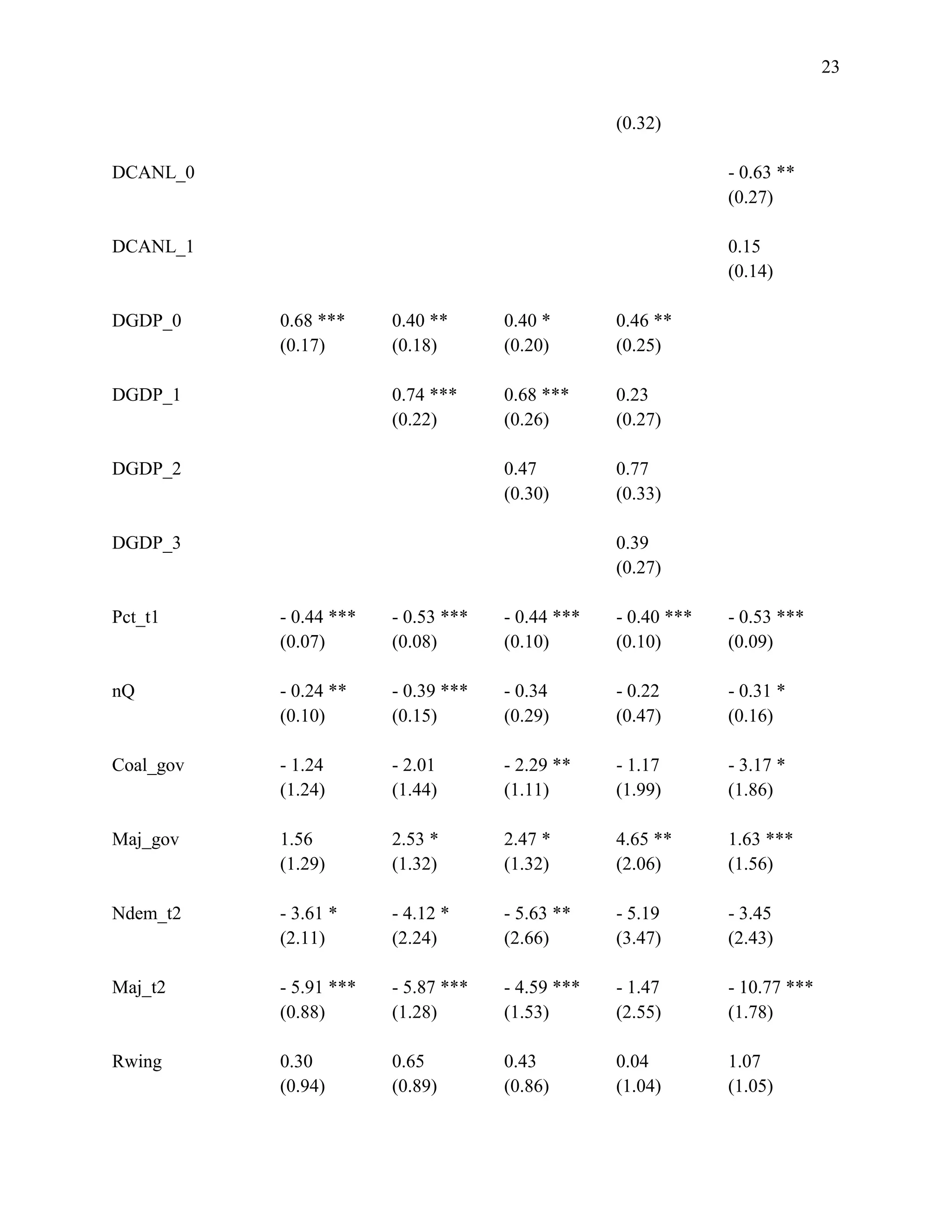

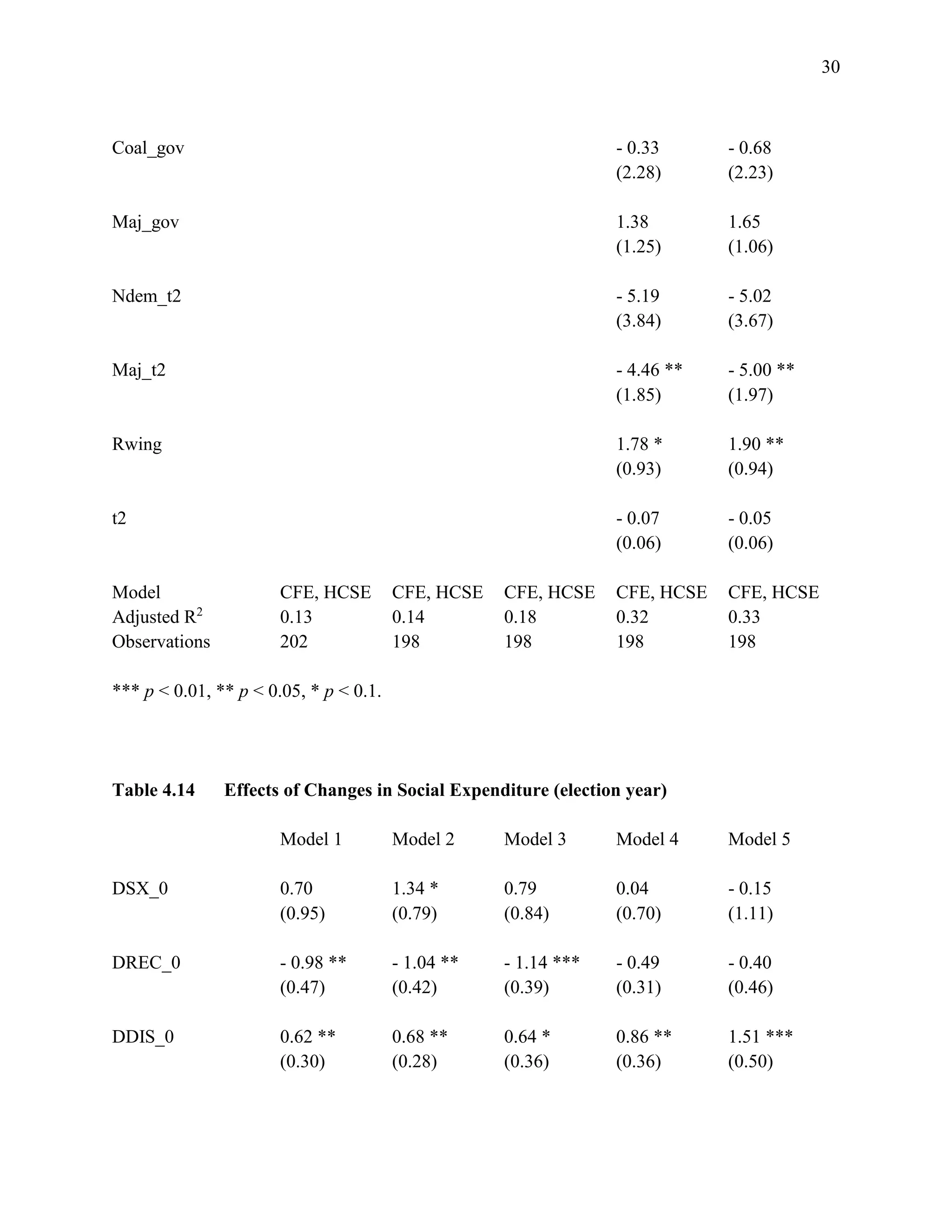

Table 4.8 presents election-year estimates of changes in general government net lending on

incumbent vote share. The results are consistent across all models: voters reward governments

for expansionary fiscal policies in the year of election. In Tables 4.9 and 4.10, I replace DNL_trm

and DCANL_trm with variables measuring lagged changes in the fiscal deficit. Vote share

increases significantly with the election-year deficit in each model (p < 0.05), except for Table

4.10, Model 5, in which including three-year lags for the cyclically-adjusted deficit increases the

standard errors such that the estimated effect of DCANL_0 is significant only at α < 0.1.

However, including a third-year lag slightly increases the magnitude of DCANL_0.

[Tables 4.8 – 4.10 here]

Heterogeneous effects of changes in receipts, disbursements, and social expenditure

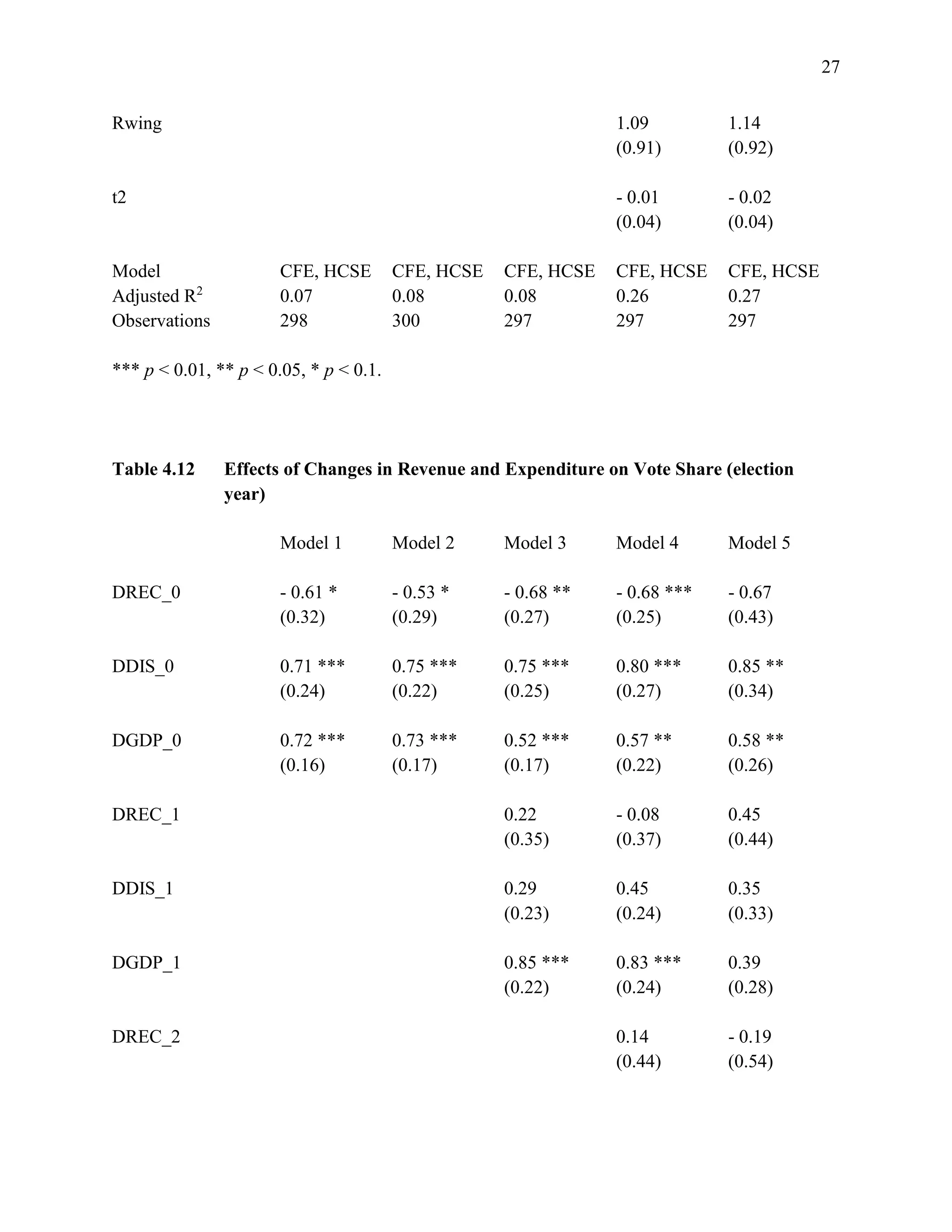

Alesina, Carloni, and Lecce (2013) claim that governments that reduce deficits through cuts in

government spending tend to survive longer than governments that reduce deficits through tax

increases. Although I find no evidence that voters reward governments for fiscal adjustments –

and consistently find that voters punish contractionary fiscal policies in election years – it is

possible that voters respond differently to tax versus spending measures when sanctioning

incumbents. To test for potentially heterogeneous effects of expenditure-based and revenue-

based fiscal adjustments, I examine the relationship between election-term and election-year

changes in expenditure and revenue (as a share of GDP) and incumbent vote share. I present the

results in Table 4.11.

[Table 4.11 here]

Table 4.11 shows no statistically significant estimated effects of term-length changes in

government receipts or disbursements on incumbent vote share. Voters do not generally oppose

higher taxes to the extent that higher taxes correspond to higher government spending over the

course of the term (Model 1). However, voters generally oppose term-length tax hikes used to

fund fiscal contractions (Model 3). Voters tend to reward governments for increasing spending,

regardless of whether the spending leads to higher taxes or fiscal expansion (Models 2-4), though

the association is not statistically significant at conventional levels.

The estimated magnitudes of term-length fiscal variables become substantially weaker once

controlling for election-year measures (Model 5). In election years, the incumbent vote share

increases with disbursement-based changes in the budget balance. Voters generally reward

(punish) tax-based fiscal expansions (contractions), but the estimated effect is not statistically

significant. Table 4.12 presents estimates of the effects of changes in election-year revenue and

expenditure on vote share, controlling for lagged changes in fiscal variables.

[Table 4.12 here]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-9-2048.jpg)

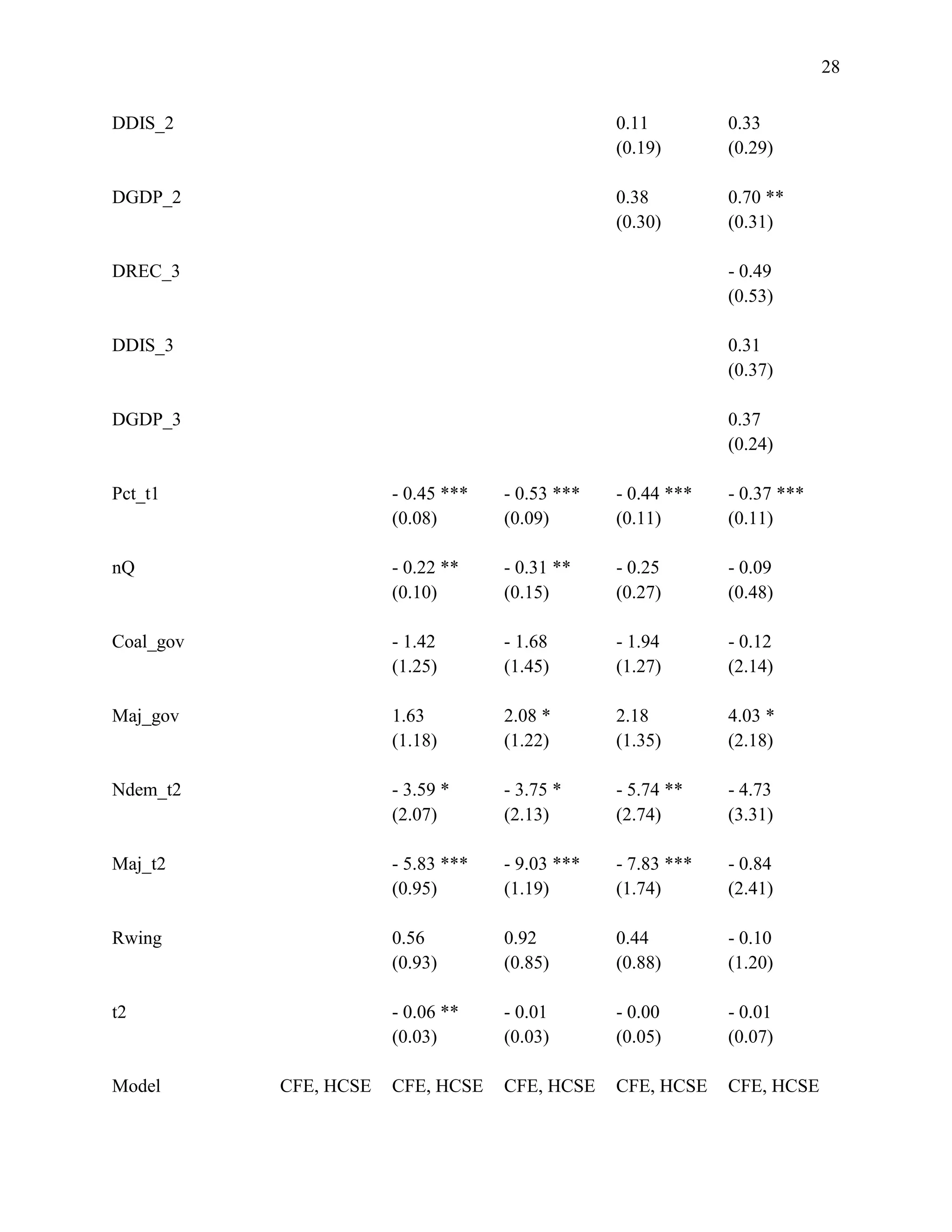

![10

Estimated election-year effects on the change in incumbent vote share remain positive and

significant for changes in disbursements and negative for changes in receipts (significant at α <

.05 in Model 3). Prior annual changes in fiscal variables have no significant effect on incumbent

vote share once controlling for election-year changes in receipts and disbursements.

Voters may plausibly evaluate changes in social (or welfare) expenditure differently than

changes in other forms of government expenditure (Pierson 1996). Yet recent research has

demonstrated no significant general effect on incumbent vote share of changes in replacement

rates for sick pay, unemployment insurance, and public pensions (Armingeon and Giger 2008;

Giger and Nelson 2010). However, as the analyses in this chapter have suggested, there is no

clear prior reason to suppose that voters sanction incumbents for term-length changes in

expenditure. Moreover, it is unclear whether voters in fact respond differently to changes in

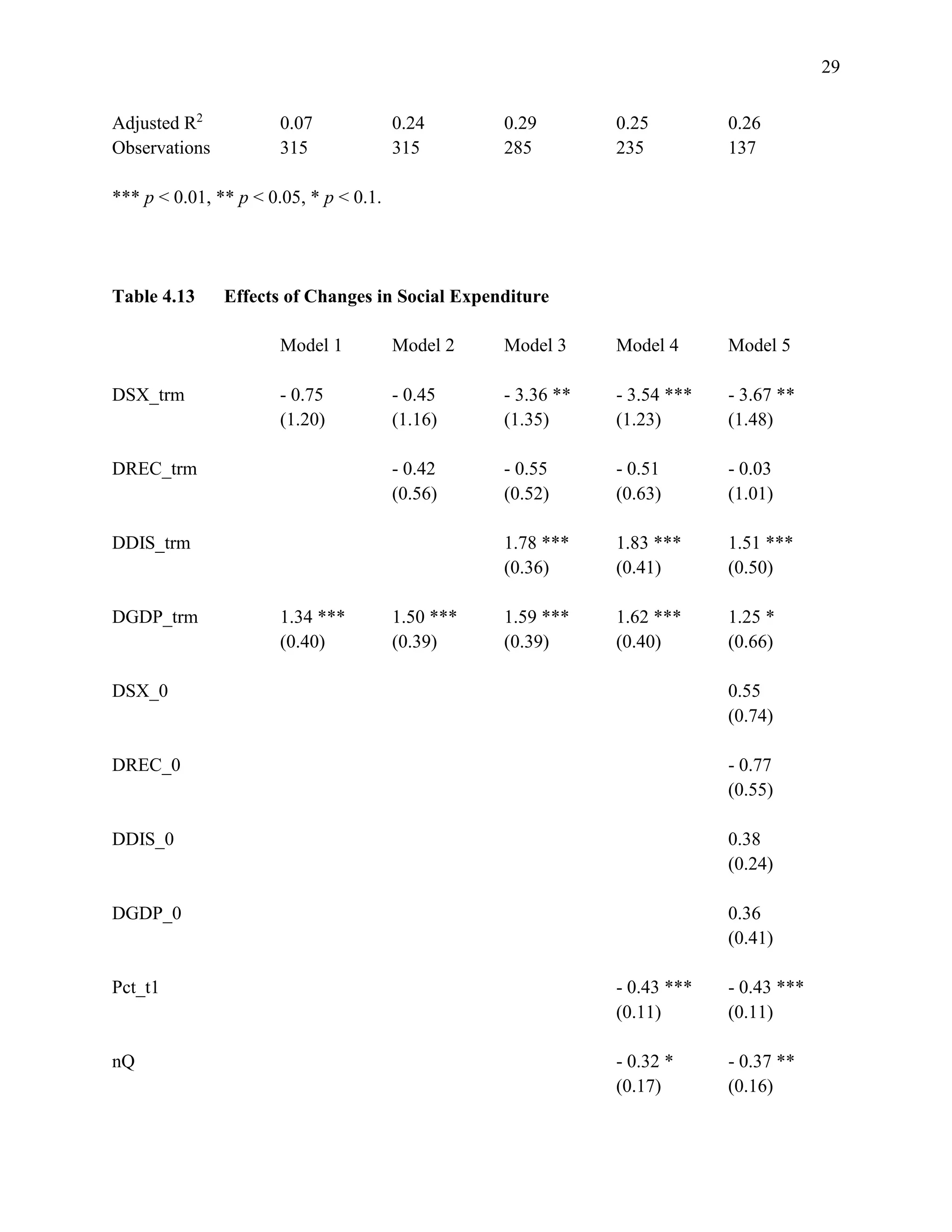

social expenditure in comparison to changes in other government disbursements. Table 4.13

examines term-length effects of changes in social expenditure. I use data from the OECD’s

(2015d) Social Expenditure Database, which includes public spending on pensions, active labor

market programs, disability and unemployment insurance, family, health, housing, and

survivors’ benefits, and “other social policy areas” (comprising 3% of social expenditure at the

OECD level).

[Table 4.13 here]

The association between changes in incumbent party vote share and term-length changes in

social expenditure is remarkably weak, regardless of whether contemporaneous changes in

government receipts are allowed to vary (Model 1) or fixed (Model 2). However, once changes

in government receipts and disbursements are both fixed, changes in social expenditure are

negatively associated with changes in incumbent vote share (p < 0.1 in Model 3; p < 0.05 in

Model 4). Voters generally reward governments for election-term expansions in non-social

expenditure, but punish governments for increasing welfare expenditure at the expense of

reductions in non-welfare government disbursements. These effects remain after controlling for

election-year changes in fiscal variables (Model 5). In contrast, incumbent vote share tends to

increase with election-year expansions in social expenditure, though the estimates are

insignificant at α < 0.05 and do not persist after controlling for two and three-year lagged

changes in social expenditure. I present these estimates in the following table.

[Table 4.14 here]

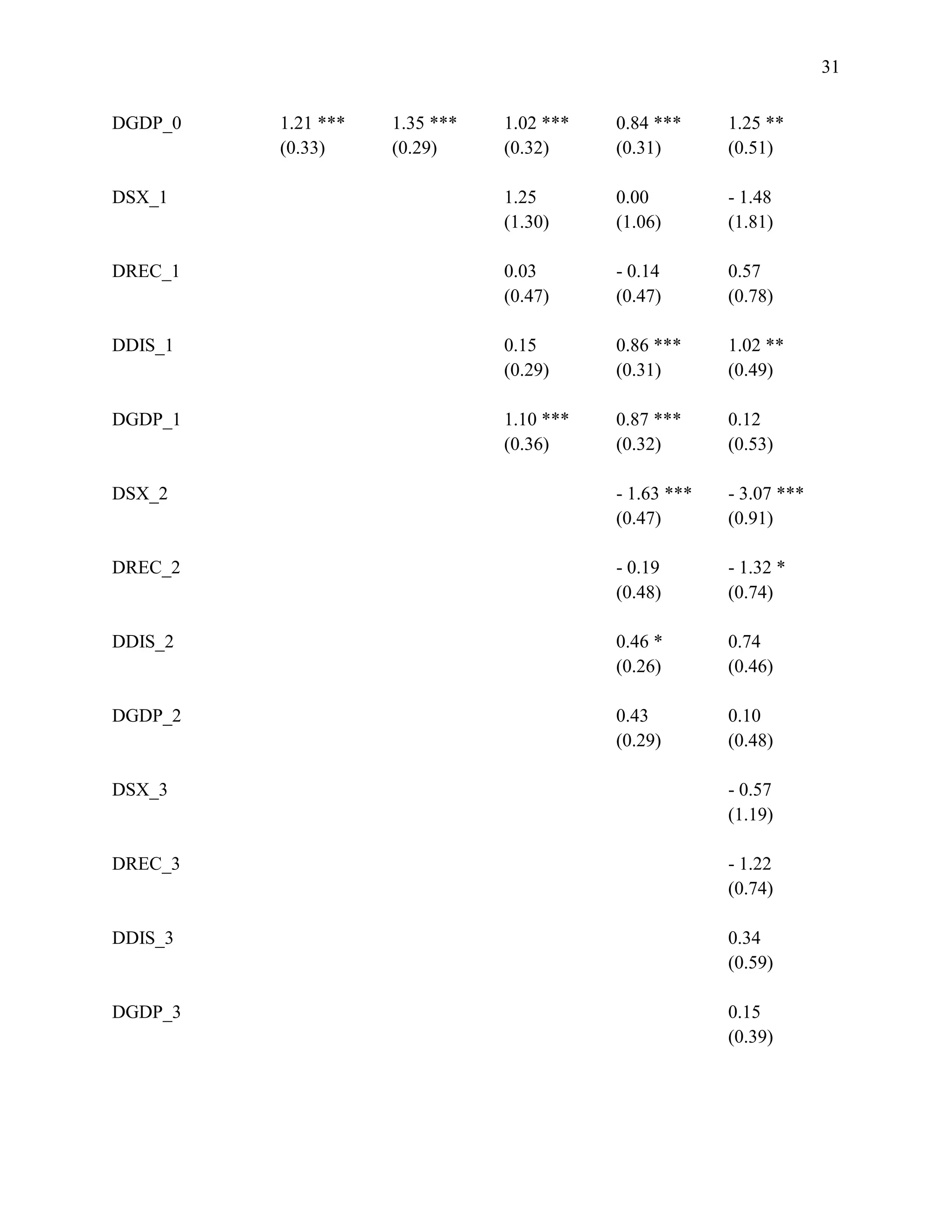

Interaction effects

The remaining models examine interaction effects between characteristics of the incumbent

government and political system and fiscal variables identified as significant determinants of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-10-2048.jpg)

![11

changes in incumbent vote share. I include four fiscal variables: change in election-year net

lending, cyclically-adjusted net lending, and disbursements (holding change in receipts constant);

and change in election-term welfare spending (holding change in receipts and disbursements

constant). I interact each fiscal variable with binary indicators of whether or not the government

facing reelection at t2 is a coalition (Coal_gov), holds a majority of seats in the lower house of

parliament (Maj_gov), is right-wing (Rwing); and whether or not the elections at t2 are one of the

first four elections held after the country’s transition to democracy (Ndem_t2), or are conducted

under majoritarian electoral rules (Maj_t2).

Models 1 and 2 in Tables 4.15-4.18 evaluate the interaction of each fiscal variable with

minority and coalition government indicator variables. Prior research has shown that voters are

less likely to sanction incumbent governments for changes in macroeconomic conditions in

political systems with lower “clarity of government responsibility.” When legislative and

executive power is dispersed among coalition partners, or when governments rely on the support

of opposition parties to pass legislation (including the government budget), voters may find it

more difficult to attribute credit or blame to the party of the chief executive. A related argument

suggests that governments can reduce the political costs associated with welfare retrenchment by

sharing responsibility for reforms with a range of political actors. Similarly, voters may be less

likely to reward or punish minority and coalition governments for changes in the level or

composition of revenue and expenditure. I present these estimates in the following tables.

[Tables 4.15 – 4.18 here]

Interestingly, voters generally punish the party of the chief executive in coalition governments –

but not in single-party administrations – for election-year reductions in the budget deficit. At the

very least, this evidence casts doubt on the applicability of the “clarity of responsibility” and

“blame sharing” hypotheses to explaining variation in the extent to which voters sanction

governments for fiscal adjustments. Voters do appear to punish the chief executive’s party in

coalition governments less than single-party governments for term-length changes in welfare

spending, holding other expenditure measures constant (Table 4.18). However, voters generally

reward governments for cutting welfare spending rather than non-welfare disbursements over the

course of the election cycle. Rather than helping primary coalition partners to spread the blame

for supposedly unpopular welfare cuts, sharing legislative responsibility with coalition partners

apparently inhibits the ability of such parties to claim credit for popular reforms. Unfortunately,

the standard error of the interaction term is too large for the effects to be significant at

conventional levels. The estimated effects are similar for minority governments, though also

insignificant.

Electoral punishment for fiscal adjustments is generally confined to governments facing

reelection under proportional electoral rules (Tables 4.15-4.17, Model 3). Yet majoritarian

systems may enable governments to claim credit for election-term reductions in welfare

expenditure (Table 4.18, Model 3). Contrary to Brender and Drazen (2005; 2008), I find no](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1d41d5f7-fae5-46d1-8513-6be43363e827-160727222245/75/ch4-11-2048.jpg)