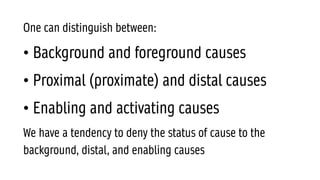

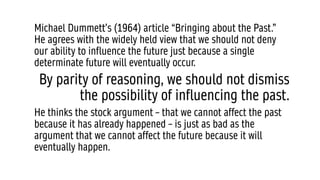

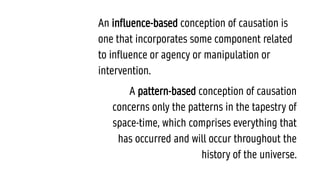

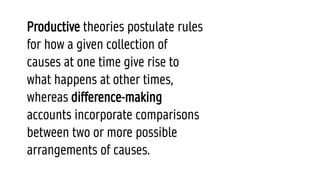

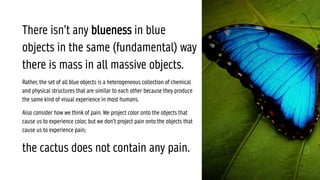

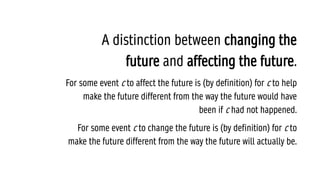

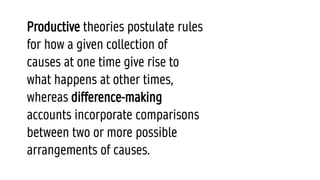

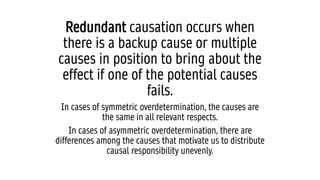

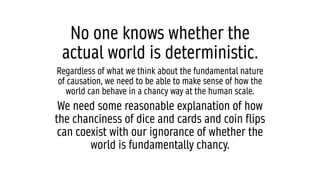

Causation is a complex topic with no comprehensive rule to determine if c causes e. There are different types of causes like background vs foreground. Productive theories see causes generating effects, while difference-making theories see causes changing outcomes. Debates about causation and ethics both involve nonlinear relationships. We cannot dismiss influencing the past just because it occurred, like we cannot change the determined future. Our understanding of causation involves both influence and patterns in events.

![“How the mind of a human being can

determine the bodily spirit in producing

voluntary actions, being only a thinking

substance. For it appears that all

determination of movement is produced

by the pushing of the thing being moved,

by the manner in which it is pushed by

that which moves it, or else by the

qualification and figure of the surface of

the latter. Contact is required for the first

two conditions, and extension for the

third. [But] you entirely exclude the latter

from the notion you have of body, and the

former seems incompatible with an

immaterial thing.” (Princess Elisabeth to

Descartes, May 1643)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/causationbydouglaskutach-230829033510-e31d462d/85/Causation-24-320.jpg)