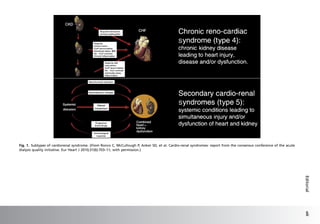

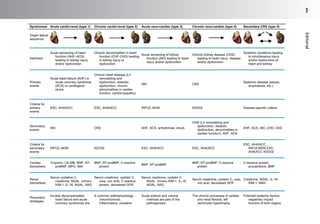

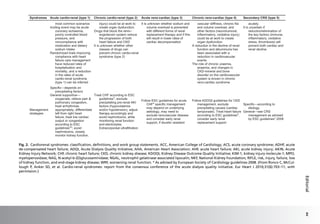

This document discusses anemia in patients with heart failure and kidney disease (cardiorenal anemia). It notes that anemia is common in these patients and associated with higher mortality and costs. The pathophysiology of cardiorenal disease and anemia are both multifactorial, involving interactions between cardiac function, renal dysfunction, inflammation, and other factors. The document outlines five subtypes of cardiorenal syndrome based on whether heart or kidney dysfunction is acute or chronic. It emphasizes that a multidisciplinary approach is needed to manage cardiorenal anemia given its complex causes.

![responses, hemodilution, iron deficiency, impaired

ability to use available iron stores,10

bone marrow

suppression due to cytokines (eg, tumor necrosis

factor a [TNF-a], interleukin [IL]-1, IL-6, and

C-reactive protein), blunted bone marrow respon-

siveness to erythropoietin, impaired iron mobiliza-

tion, and effects of medications. Aspirin and

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors11

contribute to the anemia potentially through the

actions of hematopoesis inhibitor, N-acetyl-seryl-

aspartyl-lysyl-proline.12

IL-6 stimulates the

production of hepcidin in the hepatic cells, which

blocks absorption of iron in duodenum and

down-regulates ferroprotein expression, which in

turn prevents release of iron from total body

stores.13

In contrast, TNF-a and IL-6 inhibit eryth-

ropoietin production in the kidney by activating the

GATA-binding protein, GATA2, and nuclear factor

kB and also inhibits proliferation of bone marrow

erythroid progenitor cells.3,4,13

Some have used

erythropoietin receptor–stimulating agents or

intravenous iron to correct the anemia of heart

failure, but concern has arisen about the true

effectiveness of this approach and morbidity asso-

ciated with the therapy. The Reduction of Events

with Darbopoeitin Alfa in Heart Failure is a large-

scale, phase III, placebo-controlled, randomized,

morbidity and mortality clinical trial designed to

clarify these issues and will likely be finished

recruiting in 18 months.14

To unravel these complex interactions in cardi-

orenal anemia, Anil Agarwal, MD, Stuart Katz,

MD, and Ajay Singh, MD, have assembled a multi-

disciplinary team of experts in this field. In our

opinion, their multidisciplinary approach is essen-

tial to ensure that patients with cardiorenal anemia

stay in the pink of health.

Ragavendra R. Baliga, MD, MBA

Division of Cardiovascular Medicine

The Ohio State University

Columbus, OH, USA

James B. Young, MD

Division of Medicine and Lerner

College of Medicine, Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, OH, USA

E-mail addresses:

Ragavendra.Baliga@osumc.edu (R.R. Baliga)

YOUNGJ@ccf.org (J.B. Young)

REFERENCES

1. Allen LA, Anstrom KJ, Horton JR, et al. Relationship

between anemia and health care costs in heart

failure. J Card Fail 2009;15(10):843–9.

2. Tanner H, Moschovitis G, Kuster GM, et al. The prev-

alence of anemia in chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol

2002;86(1):115–21.

3. Anand IS. Anemia and chronic heart failure implica-

tions and treatment options. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;

52(7):501–11.

4. Dec GW. Anemia and iron deficiency–new thera-

peutic targets in heart failure? N Engl J Med 2009;

361(25):2475–7.

5. Baliga RR, Young JB. ‘‘Stiff central arteries’’

syndrome: does a weak heart really stiff the kidney?

Heart Fail Clin 2008;4(4):ix–xii.

6. Ronco C, McCullough P, Anker SD, et al. Cardio-

renal syndromes: report from the consensus confer-

ence of the acute dialysis quality initiative. Eur Heart

J 2010;31(6):703–11.

7. Ronco C, Haapio M, House AA, et al. Cardiorenal

syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52(19):1527–39.

8. Nanas JN, Matsouka C, Karageorgopoulos D, et al.

Etiology of anemia in patients with advanced heart

failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48(12):2485–9.

9. Felker GM. Too much, too little, or just right?: untan-

gling endogenous erythropoietin in heart failure.

Circulation 2010; 121(2):191–3.

10. Opasich C, Cazzola M, Scelsi L, et al. Blunted eryth-

ropoietin production and defective iron supply for

erythropoiesis as major causes of anaemia in patients

with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2005;26(21):

2232–7.

11. Ishani A, Weinhandl E, Zhao Z, et al. Angiotensin-

converting enzyme inhibitor as a risk factor for

the development of anemia, and the impact of

incident anemia on mortality in patients with left

ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;

45(3):391–9.

12. van der Meer P, Lipsic E, Westenbrink BD, et al. Levels

ofhematopoiesisinhibitorN-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-

proline partially explain the occurrence of anemia in

heart failure. Circulation 2005;112(12):1743–7.

13. Weiss G, Goodnough LT. Anemia of chronic disease.

N Engl J Med 2005;352(10):1011–23.

14. McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Diaz R, et al. Design of the

reduction of events with darbepoetin alfa in heart

failure (RED-HF): a phase III, anaemia correction,

morbidity-morality trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2009;11:

795–801.

Editorialxvi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cardiorenalanemiahfclinics-160204111316/85/Cardio-renalanemiahf-clinics-6-320.jpg)