The document discusses trends in retail banking and how banks need to adapt to customers' digital lifestyles. It notes that while other industries have embraced new technologies, banking has been slow to change. Banks still focus too much on products rather than customers. However, technologies like mobile and social media offer opportunities if banks make the customer experience the priority. The document provides examples of innovative services, such as Apple allowing in-store purchases with iPhones, that banks could learn from. It argues that for banking services to succeed, they must consider customers' context, convenience and digital habits.

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

DRIVERS

15

Service

AUTHORS

Matthias Kröner is the CEO and spokesman of FIDOR BANK AG, which he co-founded.

At the age of 32, he became the youngest board member of the German virtual bank, DAB

Bank AG. He helped establish the first online brokerage in continental Europe, and is one of

the most highly profiled and skilled managers in the area of social banking with great exper-

tise in Internet.

kroener[at]fidor.de

Stephan Czajkowski is a coach and freelance consultant for transformation projects in

the banking industry. He helped establish DAB Bank AG and led the retail banking sector

of DAB Bank AG as Managing Director. In his consulting work, he follows the principles of a

solution-focusedmethodologyandiscertifiedasaBTM2 transformationmanager.Heisthe

author of the Next Generation Banking study.

czajkowski[at]dein-werk.net

Prof. Dr. Axel Uhl is head of the Center of Excellence for Business Innovation within

Business Transformation Services at SAP. He is also the president of the Business Trans-

formation Academy (BTA), a global think tank organized as a Swiss non-profit organiza-

tion. Sine 2009 Uhl has been a professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW).

a.uhl[at]sap.com

INTERNET LINKS

►► Some banks are already demonstrating the mobile banking of the future. Scan the QR code or click

the URL below, take a look at the video, and ask yourself how far your current bank offerings are

away from the future trends shown in the video.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mifamWf4Zf0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-15-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

DRIVERS

23

Service

AUTHOR

Axel Gloger is Chairman of the think tank Trendintelligence, a company that deliv-

ers future strategies for businesses. He serves as a board member of various lead-

ing service companies. His major contribution in this role is his expertise in strategy

and his ability to bring up the questions nobody else asks. He is the author of many

hands-on books, and he is the founder of the blog www.ueber-morgen.net. Axel

Gloger studied economics at the universities of Bonn, Freiburg im Breisgau, and Co-

logne. Later on, he upgraded his set of strategic skills at Insead (Fontainebleau) and

ESMT (Berlin). He lives with his family in the Rhine area.

axel[at]gloger.biz

REFERENCES

►► Deskwanted.com (Eds.) (2013). Global Coworking Census 2013. 2498 coworking spaces in 80

countries. Berlin.

►► Drucker, P. F. (1985). Managing in turbulent Times. New York: Harper & Row.

►► Gloger, A. (2012). Über_Morgen. Was Ihr Unternehmen in Zukunft erfolgreich macht. Wien: Linde.

►► Plöger, P. (2010). Arbeitssammler, Jobnomaden und Berufsautisten. Viel gelernt und nichts ge-

wonnen. Das Paradox der neuen Arbeitswelt. München: Carl Hanser Verlag.

►► Tapscott, D., Williams, A. (2006). Wikinomics. How Mass Collaboration changes everything. Lon-

don: Portfolio.

INTERNET LINKS

►► Betahaus (Berlin, Germany) www.betahaus.com/berlin

►► Burooz (Brussels, Belgium) www.burooz.be

►► Citizen Space (San Francisco, USA) www.citizenspace.us

►► Club Workspace (London, UK) http://club.workspacegroup.co.uk

►► Combinat 56 (Munich, Germany) www.combinat56.de

►► Hutfabrik (Vienna, Austria) www.hutfabrik.com

►► Mobilesuite (Berlin, Germany) www.mobilesuite.de

►► Mutinerie (Paris, France) www.mutinerie.org

►► The Hub (Zurich, Switzerland) www.hubzurich.org

But despite all the excitement, there are

also setbacks in the co-working indus-

try, as the market leader in Berlin discov-

ered in 2013. Betahaus could not rep-

licate its success in other locations. Its

Cologne co-working space closed down

in mid-April 2013, and the Hamburg office

went bankrupt at the beginning of sum-

mer. The reason: not enough tenants. It

seems like not every city has the same

potential for this innovative concept. Also

other co-working-space related projects

had to shut down, like the industry portals

deskwanted.com and Hallenprojekt.de.

Co-working may have the wind in its sails,

but it is the rules of the market economy

that count. Competition is tough, and not

every location is automatically going to

be a success. In particular for mediocre

providers whose ideas, location, pricing,

and service do not add up, there is only

one path – the market will soon weed

them out.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-23-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

39

METHODOLOGY | RESEARCH

Service

AUTHORS

Niz Safrudin is a PhD candidate and Research Associate at Queensland University

of Technology (QUT), Brisbane, Australia. Her research on Business Transformation

Management (BTM) is funded by the SAP BTA. She investigates how services from

various management disciplines are composed and orchestrated in BTM, inspired by

jazz music. Niz’s background is in Business Process Management (BPM), where her

Honors study on business process design won a best paper award at a BPM confer-

ence in the USA.

norizan.safrudin[at]qut.edu.au

Prof. Dr. Michael Rosemann is Professor and Head of the Information Systems School,

Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He is the author/editor of seven books and

more than 200 refereed papers. Dr. Rosemann’s main areas of research are Business

Process Management, Innovation Management, and Research Management. He has es-

tablished the Woolworths Chair for Retail Innovation and the Brisbane Airport Corporation

Chair in Airport Innovation at QUT.

m.rosemann[at]qut.edu.au

Prof. Dr. Jan Recker is holder of the Woolworths Chair of Retail Innovation and Profes-

sor for Information Systems at Queensland University of Technology (QUT). He is also

a Fellow of the Alexander-von-Humboldt Foundation. His research focuses on process

innovation, process design in organizational practice, and IT-enabled business transfor-

mations. Jan has written over 130 books, journal articles, and conference papers. His re-

search has attracted funding in excess of AUD $ 2 million from government and industry.

j.recker[at]qut.edu.au

Michael Genrich (Computer Science, MBA) is the Business Transformation Academy

Lead for Australia and New Zealand. He has over 25 years of experience in large-scale

business and technology change and has managed a number of transformation programs

from strategy through to design and execution. Throughout his career Michael has held se-

nior leadership roles in two global management-consulting firms. He is an accredited train-

er for SAP’s Business Transformation Methods and a Design Thinking coach.

michael.genrich[at]sap.com

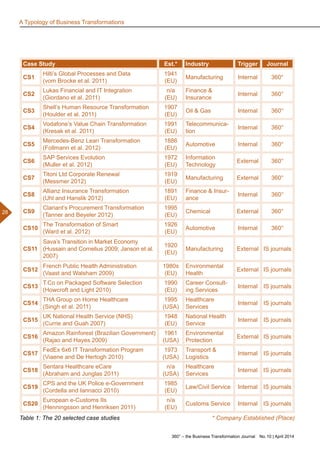

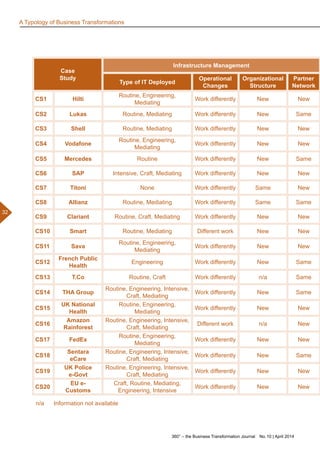

transformations that were classified us-

ing 7 attributes which were condensed

to two dimensions. The resulting 2x2

matrix depicts four types of business

transformations, namely: radical, archi-

tectural, modular, and incremental trans-

formation. Senior management and key

stakeholders can benefit from this typol-

ogy in order to ascertain what kinds of

resources are required to achieve the

intended type of transformation. Strate-

gy, Value, and Risk Management play a

crucial role during the initial or planning

phases of the business transformation.

Importantly, having an awareness of the

attributes can serve as key contextual

information when deducing which ap-

proaches are useful and relevant based

on similar cases, which in turn can serve

as crucial knowledge and information in

increasing the likelihood of a successful

transformation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-39-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

40

A Typology of Business Transformations

Service

REFERENCES

►► Abraham, C., Junglas, I. (2011). From cacophony to harmony: A case study about the IS imple-

mentation process as an opportunity for organizational transformation at Sentara Healthcare. The

Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 20(2), 177–197.

►► Cordella, A., Iannacci, F. (2010). Information systems in the public sector: The e-Government

enactment framework. The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 19(1), 52 – 66.

►► Currie, W. L., Guah, M. W. (2007). Conflicting institutional logics: a national program for IT in the

organisational field of healthcare. J Inf technol, 22(3), 235 – 247.

►► Dehning, B., Vernon, J. R., Zmud, R. W. (2003). The Value Relevance of Announcements of Trans-

formational Information Technology Investments. MIS Quarterly, 27(4), 637 – 656.

►► Doty, D. H., Glick, W. H. (1994). Typologies as a Unique Form of Theory Building: Toward Improved

Understanding and Modeling. The Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 230 – 251.

►► Follmann, J., Laack, S., Schütt, H., Uhl, A. (2012). Lean Transformation at Mercedes-Benz. 360°

– the Business Transformation Journal (3), 38 – 45. Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue3/

flipviewerxpress.html?pn=38 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Giordano, G., Lamy, A., Janasz, T. (2011). Who's The Leader? Financial IT Integration at a Global

Insurance Company. 360° – the Business Transformation Journal (1), 52 – 59. Available from: http://

www.360-bt.com/issue1/flipviewerxpress.html?pn=52 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Hatch, M. J., Cunliffe, A. L. (2013). Organization theory: Modern, symbolic, and postmodern per-

spectives. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

►► Henderson, R. M., Clark, K. B. (1990). Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing prod-

uct technologies and the failure of established firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 9 – 30.

►► Henningsson, S., Henriksen, H. Z. (2011). Inscription of behaviour and flexible interpretation in

Information Infrastructures: The case of European e-Customs. The Journal of Strategic Information

Systems, 20(4), 355 – 372.

►► Houlder, D., Wokurka, G., Günther, R. (2011). Shell Human Resources Transformation. 360° – the

Business Transformation Journal (2), 46 – 52. Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue2/flipview-

erxpress.html?pn=46 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Howcroft, D., Light, B. (2010). The social shaping of packaged software selection. Journal of the As-

sociation for Information Systems, 11(3)

►► Hussain, Z. I., Cornelius, N. (2009). The use of domination and legitimation in information systems

implementation. Information Systems Journal, 19(2), 197 – 224.

►► Janson, M., Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., Zupančič, J. (2007). Prospering in a transition economy

through information technology-supported organizational learning. Information Systems Journal,

17(1), 3 – 36.

►► Kresak, M., Corvington, L., Wiegel, F., Wokurka, G., Teufel, S., Williamson, P. (2011). Vodafone

Answers the Call to Transformation. 360° – the Business Transformation Journal (2), 54 – 66.

Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue2/flipviewerxpress.html?pn=54 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Markus, M. L., Benjamin, R. I. (1997). The Magic Bullet Theory in IT-Enabled Transformation.

MIT Sloan Management Review, 38(2), 55 – 55 – 68.

►► Merton, R. C. (2013). Innovation Risk: How to Make Smarter Decisions. Harvard Business Review,

91(4).

►► Messmer, M. (2012). Titoni Ltd. - An Independent Swiss Watch Brand in China. 360° – the Busi-

ness Transformation Journal (4), 68 – 75. Available from: http://360-bt.com/issue4/flipviewerxpress.

html?pn=68 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Morgan, R. E., Page, K. (2008). Managing business transformation to deliver strategic agility.

Strategic Change, 17(5 – 6), 155 – 168.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-40-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

41

METHODOLOGY | RESEARCH

►► Müller, O., vom Brocke, J., von Alm, T., Uhl, A. (2012). The Evolution of SAP Services. 360° –

the Business Transformation Journal (3), 48 – 56. Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue3/

flipviewerxpress.html?pn=48 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and

future of the concept. Communications of the association for Information Systems, 16(1), 1 – 25.

►► Rajao, R., Hayes, N. (2009). Conceptions of control and IT artefacts: an institutional account of

the Amazon rainforest monitoring system. J Inf technol, 24(4), 320 – 331.

►► Safrudin, N., Recker, J. (2012). A Typology for Business Transformations. Paper presented at the

Australasian Conference in Information Systems (ACIS2012). Melbourne, Australia.

►► Singh, R., Mathiassen, L., Stachura, M. E., Astapova, E. V. (2011). Dynamic capabilities in home

health: IT-enabled transformation of post-acute care. Journal of the Association for Information

Systems, 12(2), 2.

►► Tanner, C., Beyeler, P. (2012). Clariant and the Networked Economy. 360° – the Business

Transformation Journal (6), 54 – 65. Available from: http://360-bt.com/issue6/flipviewerxpress.

html?pn=54 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Uhl, A., Gollenia, L. A. (2012). A Handbook of Business Transformation Management Methodol-

ogy. Farnham, UK: Gower Publishing Limited.

►► Uhl, A., Hanslik, O. (2012). PRO3 at Allianz – A New Dimension of Customer Centricity. 360°

– the Business Transformation Journal (5), 50 – 61. Available from: http://360-bt.com/issue5/

flipviewerxpress.html?pn=50 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Vaast, E., Walsham, G. (2009). Trans-Situated Learning: Supporting a Network of Practice with

an Information Infrastructure. Information Systems Research, 20(4), 547 – 564.

►► Viaene, S., De Hertogh, S. (2010). Enterprise-wide business-IT engagement in an empowered

business environment: the case of FedEx Express EMEA. J Inf technol, 25(3), 323 – 332.

►► vom Brocke, J., Petry, M., Schmiedel, T. (2011). How Hilti Masters Transformation. 360° – the

Business Transformation Journal (1), 38 – 47. Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue1/

flipviewerxpress.html?pn=38 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

►► Ward, J., Stratil, P., Uhl, A., Schmid, A. (2012). Smart Mobility – An Up-and-Down Ride on the

Transformation Roller Coaster. 360° – the Business Transformation Journal (7), 44 – 55. Available

from: http://360-bt.com/issue7/flipviewerxpress.html?pn=44 [Accessed 31.03.2014].

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Assoc. Prof. Michael zur Muehlen at Stevens Institute

of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, for his invaluable feedback on the research-in-progress

work, and Rita Strasser at the Business Transformation Academy for her helpful input and assistance in

preparing this article.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-41-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

52

Conclusion

Globally, automotive companies are slow-

ly beginning to hear the call to action and

are starting to reassess their business

models and to reevaluate the status quo.

Many companies have recognized the

importance of a successful big data strat-

egy in this transformation and are shifting

their investment focus accordingly. Fol-

lowing our interviews with the DAX mul-

tinationals, it is too early to judge wheth-

er the steps they have taken to embrace

the potential offered by big data will be

sufficient to guarantee success; fur-

thermore it is unclear whether these in-

vestments are being made fast enough.

Despite several obvious success stories

published by the frontrunners, there are

a number of pitfalls and challenges au-

tomotive companies must overcome as

they embark on their big data journeys.

Only those companies which are able to

quickly establish and implement a suc-

cessful big data strategy, learning from

the mistakes of others and from the les-

sons from the “small data” era, will be

able to transform their businesses and

master the “zettabyte revolution”, result-

ing in a strengthened competitive posi-

tion and boosted market shares.

Service

AUTHORS

Michael Voigt is a Business Transformation Chief within the SAP Business Transfor-

mation Services organization in Germany. With an international track record of more

than 16 years in the automotive industry he leads premium partnership programs as a

senior executive advisor and program manager for major automotive customers. Prior

to SAP he worked for Siemens VDO, Accenture, and BMW. He holds a graduate degree

in mechanical engineering from the University of Munich and a graduate degree in gen-

eral engineering from EPF Graduate School of Engineering in Paris.

m.voigt[at]sap.com

Christopher Bennison is a Business Transformation Senior Consultant within the SAP

Business Transformation Services organization in Germany. During his 13 year career

at SAP, he has gained broad exposure to the automotive industry, particularly in the retail

and wholesale sectors, working on a wide range of business transformation and solution

implementation projects across the globe. Prior to joining consulting, he spent 6 years

working in product development at SAP. He holds a graduate degree in economics from

Loughborough University in the United Kingdom.

chris.bennison[at]sap.com

Prof. Dr. Maik Hammerschmidt is Professor of Marketing and holds the Chair of In-

novation Management at the University of Goettingen. His current research focuses on

marketing analytics, technology and innovation management, and social media market-

ing. He has co-authored and co-edited four books on marketing performance and mar-

keting efficiency and has published in renowned journals such as Journal of Marketing,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, and Journal of Service Research. He has

received numerous awards for his academic achievements, including an Overall Best Pa-

per Award of the American Marketing Association.

maik.hammerschmidt[at]wiwi.uni-goettingen.de

Gaining Traction](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-52-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

53

METHODOLOGY | RESEARCH

REFERENCES

►► BITKOM (2013). Management von Big-Data-Projekten. Report. BITKOM e.V.

►► Bodkin, R. (2013). The big data Wild West: The good, the bad and the ugly. September 2013. Avail-

able from: http://gigaom.com/2013/09/14/the-big-data-wild-west-the-good-the-bad-and-the-ugly/

[Accessed 30.09.2013].

►► Brown, T. (2009). Change by Design: How Design Thinking Can Transform Organizations and Inspire

Innovation. New York: HarperCollins.

►► Brynjolfsson, E. (2012). How Does Data-Driven Decision Making Affect Firm Performance, MSI Big

Data Conference, Conference Summary, December 2012.

►► Brynjolfsson, E., Hitt, L., Kim, H. (2011). Strength in Numbers: How Does Data-Driven Decision

Making Affect Firm Performance?, MIT Working Paper, April 2011.

►► Chen, H., Chiang, R. H., Storey, V. C. (2012). Business Intelligence and Analytics: From Big Data to

Big Impact. MIS Quarterly, 36 (4), 1165 – 1188.

►► Deighton, J. (2012). What Will Big Data Mean for Marketers? June 2012. Available from: http://www.

msi.org/articles/what-will-big-data-mean-for-marketers/ [Accessed 10.02.2013].

►► Dumbill, E. (2012). What is Apache Hadoop? Available from: http://strata.oreilly.com/2012/02/what-

is-apache-hadoop.html [Accessed 10.03.2014].

►► Gantz, J., Reinsel, D. (2012). The Digital Universe in 2020. Report. December 2012. IDC.

►► Gartner (2011). Pattern-Based Strategy: Getting Value from Big Data. Special Report. June 2011.

Available from http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/1731916 [Accessed 10.02.2013].

►► Harris, D. (2013). How data is changing the car game for Ford. April 2013. Available from: http://

gigaom.com/2013/04/26/how-data-is-changing-the-car-game-for-ford/ [Accessed 10.05.2013].

►► Lopez, I. (2013). Big Data Will Represent Billions in Automotive. November 2013. Available from:

http://www.datanami.com/datanami/2013-11-21/report:_big_data_will_represent_billions_in_auto-

motive.html [Accessed 02.12.2013].

►► Manyika, J., Chui, M., Brown, B., Bughin, J., Dobbs, R., Roxburgh, C., Hung Byers, A. (2011). Big

data: The next frontier for innovation, competition, and productivity. Report. May 2011. McKinsey

Global Institute.

►► Mayer-Schönberger, V., Cukier, K. (2013). Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live,

Work and Think. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

►► McAfee, A., Brynjolfsson, E. (2012). Big Data: The Management Revolution. Harvard Business Re-

view, 90 (10), 60 – 68.

►► Pearson, S., Casassa Mont, M. (2011). Sticky Policies: An Approach for Managing Privacy across

Multiple Parties. Computer, 44 (9), 60 – 68.

►► Rosemann, M. (2014). The Internet of Things. 360° – The Business Transformation Journal, No. 9,

pp. 6 –15.

►► Sensmeier, L. (2013). Think Big… Right Start Big Data Projects. September 2013. Available from:

http://hortonworks.com/blog/think-big-right-start-big-data-projects [Accessed 11.11.2013]

►► The Apache Software Foundation (2014). Welcome to Apache™ Hadoop®! Available from: http://

hadoop.apache.org/index.html [Accessed 10.03.2014].

►► Weiger, W., Hammerschmidt, M., Wetzel, H. (2012). Integration vs. Regulation: What Really Drives

User-generated Content in Social Media Channels? AMA Summer Educators Conference Proceed-

ings, Chicago.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-53-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

CASE STUDY

63

Service

AUTHORS

Prof. Dr. Axel Uhl is head of the Center of Excellence for Business Innovation within

Business Transformation Services at SAP. He is also the president of the Business Trans-

formation Academy (BTA), a global think tank organized as a Swiss non-profit organiza-

tion. Sine 2009 Uhl has been a professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW).

a.uhl[at]sap.com

Prof. Dr. Jan vom Brocke is Hilti chair of Business Process Management and director of

the Institute of Information Systems at the University of Liechtenstein. He is founder and

academic director of the International Master Program in IT and Business Process Man-

agement (BPM) at the University of Liechtenstein (www.bpm-education.org). Jan has

more than 15 years of experience in IT and BPM projects and has published more than

200 peer-reviewed papers in renowned outlets, including Management Information Sys-

tems Quarterly (MISQ). Jan is author and editor of 19 books including Springer’s Interna-

tional Handbook on Business Process Management. His work is widely recognized, e.g.

by the Financial Times Germany. He is an invited speaker and trusted advisor on Busi-

ness Process Management around the globe.

jan.vom.brocke[at]uni.li

REFERENCES

►► BASF (2008). SAP consolidation milestone achieved. Available from: http://www.information-ser-

vices.basf.com/itr/BISInternet/en/content/press/press_releases/2008/20080312_sap_cobalt_pace

[Accessed 19.10.2013].

►► Kresak, M., Corvington, L., Wiegel, F., Wokurka, G., Teufel, S., Williamson, P. (2011). Vodafone

Answers Call to Transformation. 360° – the Business Transformation Journal, issue no. 2, 54 – 66.

Available from: http://www.360-bt.com/issue2/flipviewerxpress.html [Accessed 19.10.2013].

►► Lopez, J. (2011). Accelerating performance through GLOBE / NCE. Available from: http://www.

nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/presentations/investors_events/investor_seminar_2011/

nis2011-05-globe-nce-jlopez.pdf [Accessed 19.10.2013].

►► vom Brocke, J., Petry, M., Schmiedel, T. (2011). How Hilti Masters Transformation. 360° – the Busi-

ness Transformation Journal, issue no. 01, June 2011, 38 – 47. Available from: http://www.360-bt.

com/issue1/flipviewerxpress.html [Accessed 19.10.2013].

►► vom Brocke, J., Petry, M., Sinnl, T., Kristensen, B. Ø., Sonnenberg, C. (2010). Global Processes and

Data. The Culture Journey at Hilti Corporation. In: vom Brocke, J., Rosemann, M. (Eds.), Handbook

on Business Process Management: Strategic Alignment, Governance, People and Culture (Interna-

tional Handbooks on Information Systems) (Vol. 2, pp. 537 – 556). Berlin: Springer.

but in the same period, also separa-

ted itself from nine companies with

an annual turnover of EUR 9 billion in

the last few years alone. The integra-

tion of the new companies as well as

the release of sold shares could be

significantly improved.

2. Project ONE (2011 – 2014): In 2011,

BASF started another project, with

the aim to migrate the already heavi-

ly standardized SAP landscape onto

one global solution. This project is

not yet completed (BASF 2008).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-63-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

70

turned out to be very accurate. All stake-

holders expressed their satisfaction with

the newly built system. The last four paral-

lel releases in February 2014 are the most

recent proof of the success of the pro-

gram. Twelve other locations are on the

plan for 2014. Haywood expects every-

thing to continue as smoothly as it did so

far. So it is the right time for him to reorga-

nize the priorities on his agenda.

Obviously, running the information tech-

nology infrastructure with its mainte-

nance and service management had sec-

ond priority during the main phases of the

program. “It turns out we have been so

focused that other topics were not led pro-

actively enough. Issues such as IT Ser-

vice Management have now to be priori-

tized to keep our high level of service up,”

says Haywood.

What Haywood did not say, and is only a

rumor, is that the knowledge Gammacorp

gained during the program might be the

role model for future enterprise transfor-

mations in the parent company.

Service

AUTHORS

Alexander Schmid is a PhD student and works as a research analyst at the Business

Transformation Academy (BTA). He studied management, informatics, and biology and

holds a Master of Arts in Business Administration from the University of Zurich, Swit-

zerland. Prior to his work at the BTA, Alexander worked as a Business Intelligence and

IT consultant.

alexander.schmid01[at]sap.com

Kerstin Chaves-Castillo is a Business Enterprise Principal Consultant at SAP Busi-

ness Transformation Services. Since 2011, she has been responsible for Value Partner-

ship Engagement, supporting the Program Management of large-scale business trans-

formations. She has a Master Degree in Mathematics and Electrical Engineering from

the University of Siegen, Germany and carries the title of Global Business Transforma-

tion Manager from Business Transformation Academy (BTA).

kerstin.chaves[at]sap.com

Prof. Dr. Axel Uhl is head of the Center of Excellence for Business Innovation within

Business Transformation Services at SAP. He is also the president of the Business Trans-

formation Academy (BTA), a global think tank organized as a Swiss non-profit organiza-

tion. Sine 2009 Uhl has been a professor at the University of Applied Sciences and Arts

Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW).

a.uhl[at]sap.com

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable contributions of the anonymous CIO, the program

director, and the Industrial Director.

Shaping the Future of Gammacorp](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-70-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

BOOK REVIEW

73

“Predictive Analytics: The Power to

Predict Who Will Click, Buy, Lie, or Die”

Eric Siegel

John Wiley Sons, 2013

Hardcover – 320 pages

Neuroscientist Jeff Hawkins defines hu-

man intelligence as “the ability to see pat-

terns and predict outcomes based on pre-

vious experiences”. Similar to how our

brains process available information to

guess (= predict) the answer to a question

on a TV quiz show or whether we will en-

joy that book on Amazon.com, predictive

analytics enables machines to learn from

data in order to uncover hidden patterns

and provide fact-based “best guesses”

about the likely outcome of an event.

Yet for all the abundant opportunities to

leverage predictive analytics in the age

of big data, many managers see the top-

ic as “just statistics” or an impenetrable

black box being fed formulas in Greek let-

ters. This is where Eric Siegel’s book fills a

prevalent gap.

With “accessible to non-technical read-

ers” stamped across the front (read: no

mathematical formulas or jargon), Siegel

successfully explains predictive analyt-

ics to the masses through lively, real-world

examples: How did HP lower employee

turnover by predicting “flight risk”? Could

US retailer Target really predict which of

its customers could be pregnant in order

to deliver targeted advertising? How was

IBM’s Watson computer able to outwit hu-

man champions in a match of the popular

game show Jeopardy? And, of course, the

book includes a cornucopia of otherwise

hidden insights gleaned from big data,

such as the fact that vegetarians miss few-

er flights and people who retire early can

expect a decrease in life expectancy.

Siegel does away with many common

misconceptions about predictive analyt-

ics while setting realistic expectations of

They Knew You’d (Likely) Do That

its utility. Prediction is not about knowing

the future accurately; rather it is a tool for

predicting the most likely outcome of an

individual event based on analysis of simi-

lar past events. In other words, predictive

techniques learn from data in order to re-

veal useful patterns. This is also why such

techniques could not forecast something

like the recent financial crisis, or as Siegel

puts it, “why microscopes can’t detect as-

teroid collisions”.

Further, the narrative is careful to educate

the reader on the subtle difference be-

tween correlations discovered in data by

means of brute number crunching (ma-

chine learning) and cause-effect relation-

ships. Although the lack of a causal re-

lationship does not necessarily make a

predictive model any less adept at accu-

rate prediction, one must be careful about

inferring any causality unless the model

was designed specifically to do so.

This book does not, however, follow the

traditional “business book” format by pre-

senting an adoption roadmap for organi-

zations. Instead, Siegel does an admira-

ble job of presenting a complex, otherwise

math-laden topic in an entertaining way

that should enable managers to address

such questions as: What exactly do we

want to predict? What is the process of

creating a predictive model? How do we

apply the results? And does this raise any

ethical concerns?

The reader should close the book with

an idea of how pervasive predictive mod-

els are nowadays and how to apply them

in his or her own organization. The only

question is, what do you want to predict?

Dr. Sean Kask, an econometrician and

organizational researcher by training, is

a consultant in SAP Business Transfor-

mation Services, Switzerland.

sean.kask[at]sap.com

73

Book Review by Sean Kask](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-73-320.jpg)

![360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

COMMUNITY

79

Strategy

Program

Meta Management

as a Frame

Executive

Steering

Committee

Business

Transformation

Manager

Steering

Committee

Program

Manager

Project

Manager

Formal Management

Roles

Project

and stakeholder engagement are all key

components of the Program Manager’s

responsibility. In order to be successful,

program managers must have exemplary

soft skills as well as commercial and polit-

ical acumen.

A fatal mistake would be putting a Project

Manager in the role of a Program Manag-

er, since the two roles require a very dif-

ferent set of skills. Program Managers

have a greater breadth of responsibili-

ties than Project Managers and are re-

sponsible for the setup and day-to-day

management and delivery of the program

on behalf of the Business Transforma-

tion Manager. Program Managers over-

see multiple projects, are accountable

for achieving program outcomes, and are

likely to work with stakeholders across the

broader organization. Their focus is on

high-level specification (of why and what),

stakeholder management, benefit real-

ization, dependency management, tran-

sition management respectively change

acceptance, and integration with busi-

ness strategies.

If corners are cut and the Program Man-

agement capability is compromised, this

may introduce unnecessary risks for the

transformation. In such a case, programs

often struggle and go out of control after

three to six months. This is then often ad-

dressed by getting an external program

manager to make sure the program gets

back on track and that stakeholder confi-

dence is regained by embedding a more

rigorous degree of governance.

Project Managers

Project Managers are responsible for the

project, the project team, and the prod-

ucts the team is working on, and typically

operate cross-functionally. They are the

single point of contact for the day-to-day

management of a project, and their focus

is often narrower and deeper than that of

a Program Manager as they need to focus

on the detailed specification (of how) and

thecontrolofactivitiestoproduceproducts.

Most organizations understand well the

responsibilities of a Project Manager, of

which there could be many, depending

on the nature and content of the trans-

formation. Typically, a Project Manag-

er will plan, manage, execute, and close

a project to deliver the project outputs as

agreed with the Program Manager.

As a conclusion, the three formal man-

agement roles in transformations are dis-

tinct and have distinct functions and ca-

pabilities. Skimping on transformational

roles and capabilities in a multi-million

Euro transformation initiative is more

trouble than it is worth. Or would you –

with the goal of surviving and winning a

round-the-world yacht race – set out on

the challenging voyage without ensuring

that the right capability is on board to nav-

igate the team through unchartered wa-

ters, reach the shore on schedule, with-

in budget and with minimal damage to the

vessel en route?

Rob Llewellyn is an independent Pro-

gram Manager who has helped compa-

nies transform their strategies into reali-

ty throughout the world since the 1990s.

rob[at]consult-llewellyn.com

Read more about what it requires to be

an excellent Program Manager on the

BTA blog.

Fig. 1: Organiza-

tional structure

and formal man-

agement roles in

transformations

(source: BTA)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-79-320.jpg)

![Keiichi Matsushi-

ma and Jason G.

Slater (from left),

prototyping their

Design Challen-

ge during the

HPI part of the

GBTM training

In December 2013, I had the pleasure of

being selected by the Business Transfor-

mation Academy (BTA) to participate in

the Global Business Transformation Man-

ager (GBTM) Master Certification train-

ing. My expectations were high as the or-

ganization I work for – the United Nations

Industrial Development Organization

(UNIDO) – had recently undertaken a ma-

jor transformation known as the Program

for Change and Organizational Renewal,

which had started in 2010. This transfor-

mation initiative included the implemen-

tation of an Enterprise Resource Plan-

ning solution based on SAP. Therefore,

this seemed like a great opportunity to ap-

ply lessons learned and benchmark UNI-

DO’s transformation against the Business

Transformation Management Methodolo-

gy (BTM2) and other methodologies.

Having attended the GBTM training now,

I can say that it offers a wonderful chance

to network and share experiences with

high-end experts from SAP as well as oth-

er clients and professors who have been

involved in similar initiatives. More impor-

tantly, the program truly focuses on you

as an individual in terms of leadership and

decision making qualities – with plenty of

practical scenarios to test your bounda-

ries and competences.

The training was held in a peaceful set-

ting in Potsdam, Germany, on a secluded

island surrounded by a picturesque lake.

Expand Your Boundaries

We were a group of 25 professionals con-

sisting of clients and SAP employees,

spanning the entire globe, from Mexico to

Japan. This enabled different cultures to

come together and build ties beyond the

geographical boundaries.

Guided by experts and academics, we

delved into BTM2 and a variety of disci-

plines such as solution coaching and de-

sign thinking, and practiced this knowl-

edge immediately in the form of role plays,

case studies, and group work.

The assessment during the final two days

was designed to test our ability to apply

the skills acquired during the program.

Afterwards, the participants received in-

valuable and well-appreciated individual

feedback from the assessors.

Recently, I assumed a new role at UNIDO,

leading a team responsible for managing

and supporting an integrated and unique

SAP solution, with a mandate to ensure

its contribution to enhancing UNIDO’s

operations and service delivery. In this re-

gard, the GBTM experiences, methodol-

ogies, and acquired skills will assist me

when I meet new and exciting challenges

in this new role. Overall, the GBTM was

a great opportunity as we learned about

tools and gained knowledge which can

be used in a systematic and holistic man-

ner in practice. Even more important, we

learned a lot about ourselves, how we can

act and behave as well as where we can

improve. Such an opportunity should defi-

nitely not be missed!

Mr. Jason G. Slater, ACMA, MBA, is Chief

of Business and Systems Support Ser-

vices at the UNIDO.

j.slater[at]unido.org

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein

are those of the author and do not neces-

sarily reflect the views of the United Na-

tionsIndustrialDevelopmentOrganization.

by Jason G. Slater

360° – the Business Transformation Journal No. 10 | April 2014

80

COMMUNITY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-80-320.jpg)

![PUBLICATION DETAILS OF

360° – THE BUSINESS TRANSFORMATION JOURNAL

PUBLISHER

Business Transformation Academy (BTA)

c/o University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW)

School of Business (HSW), Institute for Information Systems (IWI)

Peter Merian-Strasse 86

CH - 4002 Basel

info[at]bta-online.com

www.bta-online.com

www.360-bt.com

The Business Transformation Academy (BTA) is a joint research project of the University of Applied Scienc-

es and Arts Northwestern Switzerland (FHNW) and SAP AG. The BTA is a Swiss non-profit association. It is

registered with the Commercial Register of the Canton of Basel-Stadt under the name “Business Transfor-

mation Academy” and under the number CH-270.6.000.679-0 (legal nature: association).

Authorized representatives: Prof. Dr. Axel Uhl, Lars Alexander Gollenia, Prof. Dr. Rolf Dornberger, Nicolas

Steib, Prof. Dr. Jan vom Brocke, Paul Stratil.

Disclaimer: Within reason the BTA strives to provide correct and complete information in this journal. How-

ever, the BTA does not accept any responsibility for topicality, correctness, and completeness of the informa-

tion provided in this journal. The BTA does not accept any responsibility or liability for the content on external

links to which this journal refers to directly or indirectly and which is beyond the control of BTA.

The material contained in this journal are the copyright works of the BTA and the authors. Copying or dissem-

inating content from this journal requires the prior written consent of the BTA and of the authors.

Legal venue is Basel, Switzerland.

Note to the reader: The opinions expressed in the articles in this journal do not necessarily reflect the views

of the BTA.

Picture Credits: © iStockphoto.com/lolloj (cover), © iStockphoto.com/martinwimmer (p. 2), www.

qrcode-monkey.de(2),www.goQR.me(15,71),©iStockphoto.com/larisa65(4/5),©iStockphoto.com/Yuri(6),

stefanoborghi.com (16, 20), Mobilesuite (19), Matee Nuserm/shutterstock.com (24), StevenRussellSmith-

Photos/shutterstock.com (30/31), © iStockphoto.com/filo (36), © iStockphoto.com/nadla (42), © iStockphoto.

com/EXTREME-PHOTOGRAPHER (44), © iQoncept/fotolia.com (45), © iStockphoto.com/kolb_art (47),

© iStockphoto.com/shironosov (54, 57), © iStockphoto.com/LeeYiuTung (61), Monkey Business Imag-

es/shutterstock.com (64), SAP AG (67, 68, 76, 77), © iStockphoto.com/benedek (71), courtesy of John

Wiley Sons Ltd (73), Niz Safrudin/BTA (76 bottom left, 77 top right), BTA/SAP (77 bottom left), Michael von

Kutzschenbach/BTA (80).

Published three to four times a year in electronic format.

EDITORIAL OFFICE

For inquiries about the journal please contact: info[at]360-bt.com.

Subscriptions: If you want to be notified when new issues are published, subscribe on

https://www.bta-online.com/newsletter and tick the box labeled “360° Journal News”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/btaonline360journalissue10-140731160624-phpapp01/85/Business-Transformation-3-T-s-Trends-Typology-Tractions-Future-81-320.jpg)