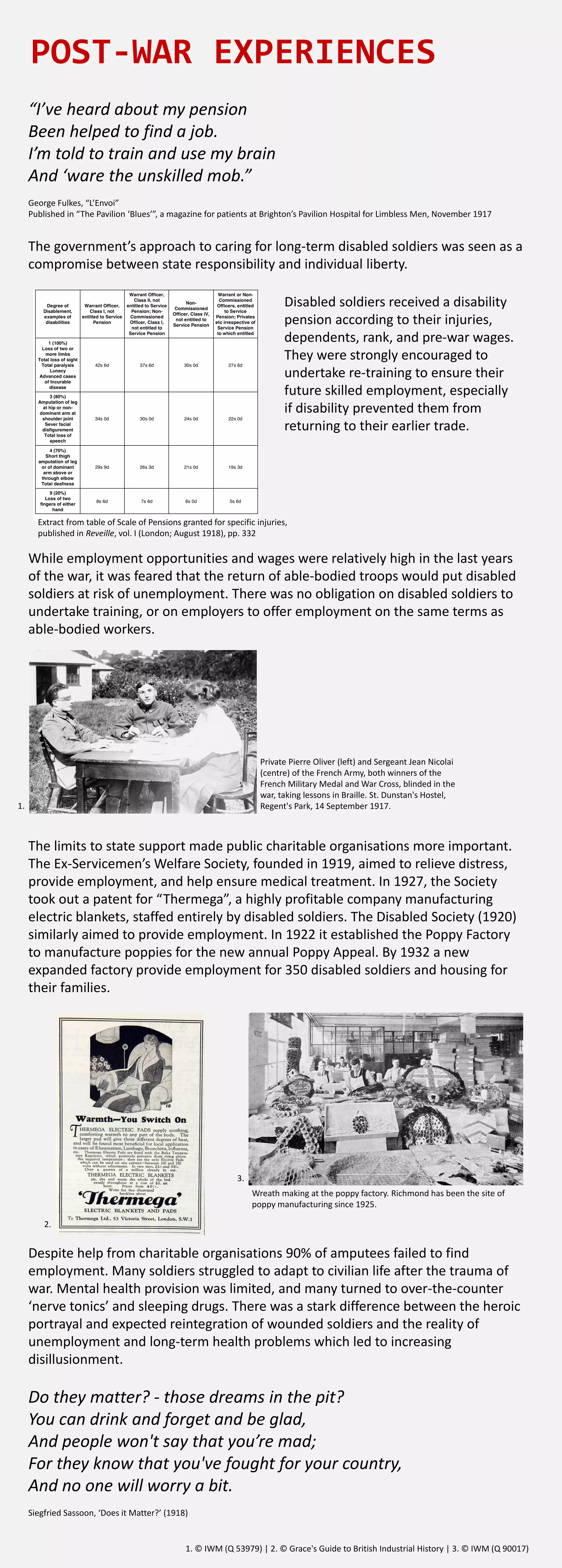

The document discusses the challenges faced by long-term disabled soldiers in post-war Britain, highlighting a lack of adequate state support and the reliance on charitable organizations for employment and rehabilitation. Despite these efforts, 90% of amputees struggled to find work, leading to disillusionment as many had difficulty adapting to civilian life and faced mental health issues. The narrative contrasts the idealized reintegration of wounded soldiers with the harsh realities of unemployment and health struggles.