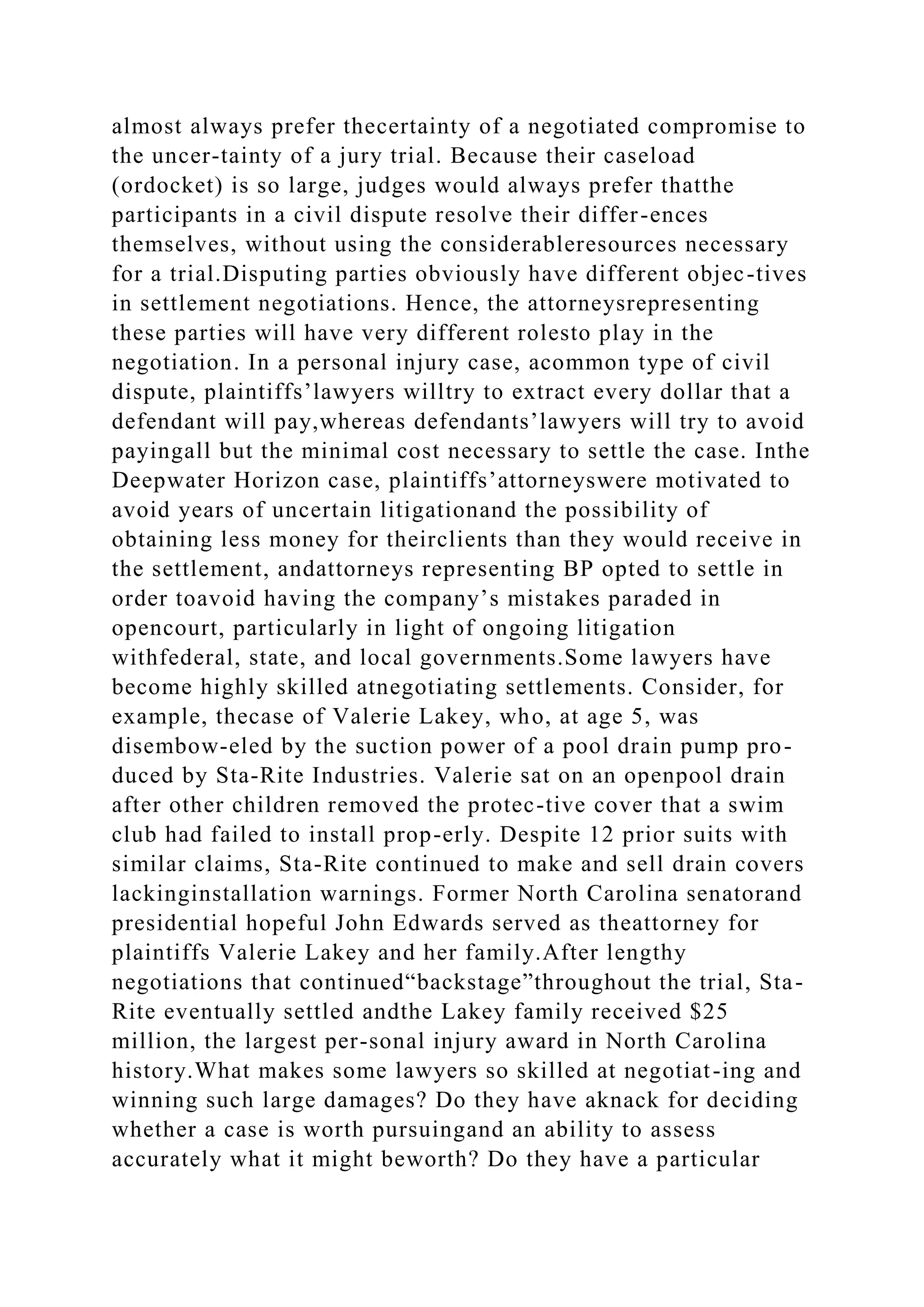

The document outlines the traditional prosecution process, emphasizing the psychological implications of trials and the prevalence of plea bargains and settlements in resolving cases. It details the various pretrial steps, including arrest, initial appearances, preliminary hearings, grand jury proceedings, and arraignment, highlighting the significant role of judges in determining case progression and bail decisions. Additionally, it discusses the psychological factors influencing these legal processes and the public's fascination with trials despite the majority of cases being settled outside the courtroom.